CHAPTER 9

Case Examples

This chapter provides case examples and guidance on how to avoid common pitfalls associated with Process Improvement implementation. It is built around real-life events that point out the value of positive, consistent, and reliable service experiences and demonstrates examples of how improvement can be made using a process improvement framework such as The Process Improvement Handbook. The case examples outlined also provide opportunities for readers to develop and enhance application skills. Each case involves the integration of content across all chapters of the handbook, and presents issues encountered in social work settings related to the practice and execution of the Process Improvement knowledge areas. These case examples were selected to illustrate specific issues and provide insights for practitioners as they execute process design and improvement efforts. The goal is to include sufficient information to highlight lessons while allowing practitioners to judge whether these lessons could apply to their context. This chapter is organized around the following case examples:

• Recognize What Failure Is: This is a study in evolving customer expectations and the cost of keeping a customer.

• Achieve Customer Delight: This case example explores consistency of experience as a driver for achieving customer delight.

• What Can Go Wrong, How to Make IT Right: In this example, reflections of implementation flexibility and agility are provided using the process-oriented landscape.

• Remove Roadblocks: A review of the value of process measurement is presented in this case example.

• Reward and Celebrate: This case example presents results through social engineering and reinforcement.

• 30 Days Gets Results: The strategic advantage to process visibility is discussed in this example.

Recognize What Failure Is

The Challenge

If you are like most people, you unconsciously interact with business processes every day but get frustrated when you are abruptly confronted with a process that doesn’t work. Frustration is a natural response when you experience a mismatch in expectations and the service provided. Process work often focuses on achieving an efficient flow of work from one step to another or has the intent to save money and time. These objectives are clearly important—but alone they are incomplete and can breed friction between expectations and delivery. Planning the human interaction experience in process design is paramount to achieving a smooth interaction experience. Below is an example of an interaction experienced in 2011 that illustrates how a mismatch in process and expectations impacts business revenue and profitability and should be taken seriously.

The Solution

I had been an Amazon.com customer for more than 10 years when I lived in Michigan before moving to Ontario, Canada, to build a Continuous Improvement organization. Bright-eyed and eager to give 20 copies of Geary A. Rummler and Alan P. Brache’s text Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space in the Organization Chart as gift to build team unity, I turned to Amazon’s Canadian website prepared to spend approximately $800.00 on the bulk order. Part of the attraction of buying from Amazon was based on free shipping and consistently positive shopping experiences in the past. The book was not listed as available to order from the Canadian site. Determined to get fast access to the book, I decided it would be worth the expense to import the books to Canada from the United States site so that I could give the gifts to my team at the next big meeting, which was in a week. I successfully ordered the books and opted for expedited delivery to Canada, which added about $15.00 to the total.

About four days later a big Amazon shipping box was at my doorstep when I returned home from work. The box had no visible damage, and when I opened it I found lots of brown packing paper bunched up at opposite ends of the box and two stacks of 10 books. Perfect. Or so I thought. I pulled the first book out and started flipping through the pages, enjoying the new book and imagining how happy I was about to make 20 employees with the gift. I set the book down and began to pull each copy out of the box and stack them on my desk. Then I noticed something unexpected. There was a black mark on the bottom of each book that extended from the top of the hard cover to the back along the pages. I looked closer. Ink had rubbed off on each book, essentially smudging the top hard cover. I was not impressed and didn’t think the books looked new at all. I began to imagine what I would feel like if someone who was my new leader handed me a book that looked like this and told me that it was a gift. I would think the person gave me a used book and would feel like it was not much of a gift at all.

Being a reasonable person who just invested more than $800.00, I hopped onto Amazon.com and found a fantastic set of customer support tools that let me upload a photo of the problem and explain the problem for their review. In my message, I asked Amazon to immediately ship out replacement books and provide return shipping for the defective books. After about 10 clicks, I noticed a note that said if you want to return your shipment, there was another process to follow. I clicked that link, filled in all the information again, and hit submit. I immediately received an RMA number (return to manufacturer authorization number) and instruction to take the box to my local mail service and pay for the return. The instruction noted that Amazon would credit my account after they received the goods. I was disappointed and frustrated. If I did what I was instructed, I wouldn’t have new books, plus I had all the bother of driving to the local mail service and paying even more money to return Amazon’s books. I felt betrayed by what I perceived was a broken promise. I decided that using RMA the way they wanted me to wasn’t good enough. I filled out another form asking that they contact me and provided my home phone number. In less than a minute, my home phone rang. I answered, and amazingly it was an Amazon employee asking me about the issue.

They already had a lot of my information from the forms I had filled out, but they did not have the pictures that I had uploaded. The employee said, “I don’t have access to that information.” So, I described the problem in as much detail as I could and told him that what would make me happy was “new” books that didn’t have smudges on them. Also, I wanted them to send out the books immediately and to have a courier pickup the box of defective books from my front step. The employee was very polite and professional and clicked away as I talked. Eventually he informed me that because I lived in Canada, he could not accommodate my request due to some problem with getting the goods back through customs. I was able to order from Canada, but I wasn’t able to return from Canada? This made no sense.

Things escalated as my frustration got the better of me. I told the representative that I was just going to throw the books away if they wouldn’t take them back and shop locally and never shop at Amazon again. Whatever their process was, it sure wasn’t helping me and I wasn’t going to be taken advantage of. Then something remarkable happened. He asked me not to destroy the books and asked that I donate them to a school or charity in my area that could use them. He said he would expedite a new shipment out immediately in recognition of my long-standing loyalty to Amazon. I felt my frustration dip, and rational thought returned. How will I know that the next shipment won’t have the same problem I asked? He said he would ensure that the warehouse would be notified of the problem and that they would make sure the quality was up to their standards.

Three days later the replacement box arrived. Twenty beautifully stacked books, just like the first shipment. As I opened the box, I took a very close look for the defect I had found the last time. Exactly the same marks and smudges on every book. Frustration! I carried the entire box of books into work the next day and plunked them down on a table in from of my team. I retold the entire story of my intent and excitement to share the fantastic book that I believed would change their lives. And then I told them the very interesting lesson I learned from my expensive Amazon lesson.

The Result

It is worth noting that Amazon did a lot of things right in their business process. They were attentive to me as a customer, they had many interactions thought out, and self-service was available on their website. They acted with integrity when trying to resolve the problem—and I would say did better than any company I had ever had experience with. They did not, however, have a complete understanding of their global business customer’s needs, there were some gaps in service processes for people like me, and they lost money in their attempt to correct the problem. Perhaps mine is a fringe case for Amazon that doesn’t affect their overall operation and they aren’t overly concerned that this happened to me. However, I haven’t shopped with Amazon Canada or US because they didn’t meet my expectations, which ironically they had raised based on 10 years of fantastic shopping experiences. In the past, I spent a few thousand dollars each year at Amazon for business and personal purchases. Now I spend that money at a local store where I can inspect the books I’m buying. Amazon lost me as a customer but gave me greater appreciation for the importance of completeness in business process design that will always work for the customer. It is exactly this appreciation that drove me to devote so much attention to the process ecosystem and process-oriented architecture. This case is written through experience from author Tim Purdie.

Case Summary

In this situation there was a conflict between the consumer’s expectations for a simple and effective method of returning products based on consistently simple and high-quality ease of making purchases. The process for purchase was very well tuned for optimal performance and volume of transactions. The consumer had learned over a lengthy period of time to be able to trust that every purchase would have the same attributes of quality and delivery that built brand loyalty and favor. While there was a reliable and “as-designed” return method for consumers to use, the fact that I received two deliveries with the exact same issue broke my trust. It appeared that no process was in place to address repeating delivery problems differently, and there were no instructions on how to resolve high-value customer issues separate from those of occasional customers.

There is an opportunity to apply the principles found in the process-oriented landscape and add this situation to the use-case library and address the process gap in order to avoid further erosion of the customer base. Resolving the original issue regarding how the blemished books moved out of the warehouse and were delivered to a customer needs to be explored more deeply in order to determine root cause and corrective process action. In addition, a larger gap in process coverage that needs further evaluation was uncovered. The volume of customers who may have received blemished books may be a very tiny number among all the retailer’s transactions. However, the notion that a high-dollar spending and long-term customer could be lost so easily needs to be explored more closely. An improvement in the retailer’s overall process would incorporate process performance monitors or alerts for this tier of customer who report back-to-back quality problems with their shipment. These situations should be routed differently for a “high-touch” service response. The investment in white-glove programs that handle priority customers in this way has proven to aid in customer retention and improve brand reputation for other organizations.

Achieve Customer Delight

The Challenge

Having had my fair share of bad retail experiences with products that needed to be returned, I was delighted when one experience actually met with the marketing hype. Over the years I have purchased a winter coat for my children every year. As kids grow quickly, the investment is usually small because the coat is intended to last only one season. However, almost without fail, every brand of coat I have purchased failed to keep my daughter warm and dry during the harsh Canadian winter, and I had experienced the anti-customer delight experience many times while dealing with the retail outlet I purchased from. Each time it left me swearing off ever buying that brand the following winter. This past winter I purchased a more expensive brand of winter coat for my 10-year-old daughter from a local chain sporting good store rather than the usual department stores I had shopped at in years past. I did this because I had two expectations—first, that a specialty store would have higher quality coats and, second, that they would have professional service representatives who would not only know the best product for my daughter’s needs but they also would intimately pick a product that would be more lasting than we had purchased before. Two hundred dollars later, we walked out of the store, my daughter happy with her purple coat and me happy that for once she would be warm and the coat wouldn’t fall apart.

The Solution

Fast-forward two months. My daughter came home from school pointing out that her industrial-looking zipper was gaping open in the middle. How could this be? With a decidedly annoyed intent to read the store a piece of my mind, I rummaged through receipts to locate the one for the coat but came up short. As most of us have come to expect, no receipt means the store has no way of knowing that the coat was purchased from them and that it won’t honor a return or replacement. While frustrating, the store does have the upper hand in this regard. However, my wife recalled that the store advertised their commitment to customer satisfaction on a large sign behind the cashier and called the store to ask what their policy was when a customer can’t locate the receipt. To our delight, they told my wife they would do a straight exchange. Off to the store my daughter and I went with some hesitation that there would certainly be some hassle about the zipper to deal with. I explained our situation to the cashier, who quickly checked the store inventory and found the very last matching coat in my daughter’s size and handed it over. No paperwork! Not even an entry into the computer. No, in fact, the cashier explained that this was very unusual for that brand of coat and that should anything go wrong with this one, I should bring it back. She further explained that if the zipper should fail on this coat, the manufacturer would ask me to take the coat to a local tailor and have them replace the zipper; I would pay the cost and bring the receipt to the retailer for reimbursement. Walking out of the store, I turned to my daughter and said, “This is why you spend a little more for quality—this never happened with your other coats!”

The Result

Reflecting on this example, there are a couple of points worth mentioning. First, because I had experience that taught me to be skeptical of retailers and their claims of customer satisfaction, I had a private expectation to be disappointed. I carried this with me into the sports specialty store. Second, I had the private expectation that paying more this time would remove the quality issue altogether and I wouldn’t have a bad experience. I also had an expectation that I wouldn’t have to keep my receipt handy as a result. These expectations were all in my head and had created a mismatch even before I walked into the store. There was an opportunity for the salesperson to inform me that included with the brand reputation was additional protection provided by the store because of their great exchange policy or their repair-at-their-cost policy. Unfortunately, they didn’t take that opportunity; as a result, the anxiety I felt when I discovered the zipper had failed and the phone call to the store could have been avoided. That anxiety had tripped off the “I’ll never shop there again” signal in my brain because I had been duped into spending more than I had in years past. That is a powerful consumer trigger that I am sure we have all felt. Alas, had the salesperson “sold” me on these qualities, I would never have had those residual emotions. Luckily for that store, their recovery was so quick and little time had passed from issue to resolution that I walked away with a happy perception of the entire experience and would very likely buy the next winter coat from that same store.

The lesson here is that customer delight is psychologically and emotionally driven by what is in the mind and experience of the customer. It is reasonable to expect retailers to look at the data on return rates of past purchases of specific brands and to measure follow-on sales by the same customer and realize something was wrong. They could have then interviewed, surveyed, and observed the problem and come up with processes that better inform customers. In addition, they could have handled returns more smoothly in an effort to make their customers happier, which would translate into future purchase loyalty, just like the expensive sporting goods retailer had clearly done. The reward to the business is many years of hundred-dollar purchases of coats.

Case Summary

A mismatch of expectations and delivery capability is the most common contributor to a lack of customer delight. Many organizations establish departments and dedicate staff to handle customer service concerns when the mismatch occurs. We argue that most mismatches could be avoided by implementing use-case scenarios for varying expectations that a customer would/could have and creating processes that guide the customer to a successful outcome. The transparency of the process is paramount as it sets an expectation that can match the planned delivery outcome.

In the winter coat return example, the value of a well-thought-out and advertised process that is followed can be observed. The retailer did what they said they would do. To the trained eye looking for process gaps, it was clear that thought had been put into the unhappy path of the process; meaning, when things don’t work as expected, how is everything expected to work. This simple notion takes a concerted amount of time to plan for, model, and ensure the right consumer outcome while maintaining profitability. A lesson within this case example also emphasizes how meeting basic service expectations can be something a consumer would qualify as meeting their criteria for service delight. Grand gestures and discounting or financial incentives aren’t always necessary—a well-designed process that works as advertised can do the trick.

What Can Go Wrong, How To Make IT Right

The Challenge

In September 2012 I took on a rip-and-replace project for a broken Customer Relationship Management (CRM) solution and a crippled business operation that needed life support. This example looks at a recent project in which a technology conversion from Microsoft CRM to Salesforce.com CRM took place. Beyond the very different business models of Microsoft and Salesforce.com, the company’s underlying business processes needed to be reviewed from top to bottom in order to understand the gaps that would be solved by using the new tool. In addition, the new gaps that were created by the procedure changes needed to work with the new tool. Every technology project faces change resistance as things evolve. In this example, the project team chose to face that potential resistance by using use-case scenarios to flush out the business goals related to performing a specific process, as well as the expectations regarding how those steps would be sequenced. The use cases were essentially microprocesses.

The Solution

With a library of use cases, the team was able to organize their work around satisfying the use cases in the most lean and efficient way possible while taking into account the business rules, dependencies, and interconnection points with other systems and processes. In effect this formed an interwoven landscape of CRM processes. This level of process coverage for real-life business situations brought about a great deal of confidence not only in the project team but in the executive team that had taken on elevated risk in deciding to switch platform CRM solutions. The coverage translated to freedom to invent, adjust, and remove processes as needed in record time. During testing, when business users uncover new user scenarios, the project team used the newly built process landscape to assess the level of impact on the project and on the overall business in order to make decisions. Questions that were easily asked and answered included, Was the functionality proposed already solved by an existing process? Could an existing process be extended to include the net new functionality? What preceding inputs are needed for this new scenario and how is the output consumed? The simplicity of having the landscape in place along with management’s discipline to be lean about the processes they adopted created a nimble CRM solution for the business that could expand as the business grows. It also matured everyone’s expectations about how process work should function and reduced the noise and confusion that had been in place prior to implementing this basic framework.

Each question can be viewed as a way to explore impact on the greater process ecosystem and drive the business stakeholders’ awareness. In this way, the business value is understood, and employees understand their contribution and impact as process operators. This synchronicity drives adherence to existing processes, efficient analysis of proposed changes, and transparency within the organization and, where appropriate, externally. The transition from one way of operating to another can be visually represented in process maps and related materials and can shorten the changeover timeline significantly.

The Result

Using this approach, the transition from the legacy CRM application to the new one took three and a half months. Without this approach, the project might have taken a year or more to implement. The president of the company remarked a week after the new CRM was operational that he had never seen a project be so successfully delivered in such a short period of time. Talented project team members aside, adoption of the process-oriented architecture foundation was the key to success because it was possible to deliver the solution with high quality and within a tight timeframe.

Case Summary

We recommend that processes be designed to be adaptive in order to ensure their longevity, low maintenance, and ease of adoption. Having said that, sometimes even well-designed processes break down and need maintenance or overhaul. Typically this occurs when an external condition changes. For example, mergers, takeovers, and major technology shifts that require integration with systems and impact extensive processes are not easily taken into account at the time the process in question is created. Nevertheless, these events happen from time to time and can create a profound disconnect in the process landscape and can have significant ripple effects that need to be handled to avoid systemic failure and profitability problems. In these situations the importance of having the base level of a process architecture and governance in place can speed up assessment of impact dramatically and ultimately provide a list of items that can be used to prioritize actions.

Remove Roadblocks

The Challenge

Catching opportunities to make improvements doesn’t stop at work; you can find them sitting in most any waiting room. A favorite lesson from reading Rummler–Brache’s Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart is that it is critically important to put in place measures that relate to what happens in between processes in addition to what happens within processes. After reviewing thousands of processes maps in my career, I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve seen process measures appear. In these situations I have coached process designers on the importance of using measures as a key driver to achieve process improvement. Having metrics about end-to-end process performance, cycle time, volume, defect rate, and similar elements is of course important in order to have some understanding of the process performance health. However, measuring independent processes and totaling their performance is not an accurate way to characterize the overall experience that a customer might have. This case example is about hospital emergency room wait times. In Canada, the statistics on the number of hours a walk-in patient with a nonlife-threatening issue waits are dismal. Think in terms of multiple hours; that’s right, it is not uncommon to wait more than 10 hours to be seen by a physician. The hospital administration may measure process performance based on the time a patient first sits in the triage chair to the time the physician assesses the patient. As long as that target time doesn’t exceed their target, they have a successful process.

The Solution

As a patient, however, you may measure the experience differently. I would simply have a personal measure that calculates the time from initial experience of pain/issue to pain/issue relief. My measure does not divide up every stage of the process for which time can be measured, that is, time waiting for initial hospital emergency room check-in, for triage, for physician assessment, for discharge, for drive time to the pharmacy, for the time for the prescription to be filled, and finally for time before medication has a satisfactory result. The hospital’s measure misses the periods of time in between discrete processes. For example, if I needed an X-ray, the time between the instruction to get an X-ray and actually receiving an X-ray is discarded. The hospital views it as a net new unrelated process. As a patient in pain, I doubt you would agree. The solution is to emphasize the customer experience for those who benefit from the process’s purpose—in this case, the patient. By aggregating the discrete processes into a superprocess, measures related to mean time to resolution can be targeted in order to ensure that any routine set of superprocesses operate using the leanest method possible. How can this be achieved in this example?

The Result

Having the proper medical equipment on hand for the treating physician to use during the initial assessment may be one solution. If an X-ray is required, the transport time to the X-ray room, the wait time for the X-ray technician, and the transport time back to the assessing doctor who is waiting for X-ray results could be eliminated. This could shave hours off the overall resolution time for this type of issue.

Case Summary

While annoyed patients may not be enough of an incentive to address the long wait time issue, hospitals are often driven by the financial impact of long wait times. Having measures in place that demonstrate the increased patient intake and the resultant positive cash flow can be a powerful message. Finding waste in processes reduces labor costs that can be turned into higher profit and/or investment in expanded services and staff. A critical eye on the end-to-end process can locate these cost holes more easily. This is done by using a combination of process ecosystem mapping techniques and associated performance measures. By using alternate-path process scenarios, an improved outcome can be modeled and later tested in a sample set of hospitals. Based on the outcome, the process can be further improved and/or released for use by a larger number of hospitals. Even small process improvements can translate into many millions of dollars of savings and justify the focus on process work.

Reward and Celebrate

The Challenge

I hate being on hold. It got me thinking about why companies allow this to happen; after all, these customers are potentially going to spend money. Walking the floor of a call center operation, you start to understand how it all works and how little understanding there is for the customer experience. Call centers notoriously underpay their workforce and enforce severe consequences for employees who don’t handle the targeted number of calls during a shift. Employee turnover is usually high as either the workers burn out from stress or management isn’t getting the right level of performance out of their workers to turn enough profit. However, there are usually a few high performers who are able to take the stress out of their job, meet their targets, and manage to stick around as long-term employees. Every call center wants to keep these workers, as they seem to have broken the secret code to success. In fact, businesses want to have more of these workers and fewer of the ones who don’t seem to keep up.

The Solution

Finding the right balance between encouragement and discipline in order to get employees to follow the planned course of action can be a real challenge. Reinforcement of compliance through recognition and reward helps to establish expectations and drive a culture of improvement for everyone. An environment that encourages employees to spot problems and report them so that they can be resolved has proven to have more successful outcomes and does so with a happier workforce. Understanding the purpose of a process and having an understanding of its goals, procedures, and expected results creates the opportunity for all employees to operate the process effectively. Setting consequences—positive ones such as a financial reward, prize, or even simple acknowledgments for doing the job well—go a long way. Other consequences, the ones we like to discourage, are equally important when building a culture of improvement.

The Result

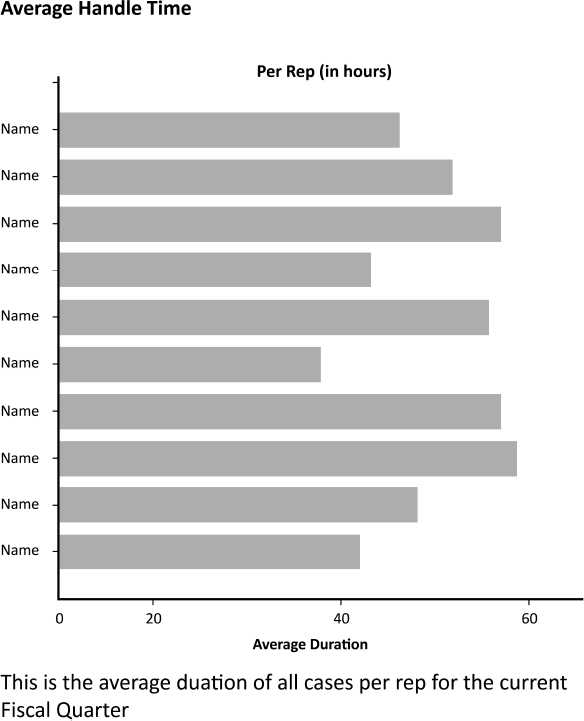

Transparency of process adherence is important in achieving awareness of potential problem spots in process design, as well as human operator contribution. Call centers typically use large displays of metrics to show performance of their employees. Figure 9-1 depicts an example of agent service performance.

FIGURE 9-1 Call Center Performance

These displays inform those who see the results and drive specific action. When there is a clear advancement in performance, call center management can reward their top performers with high praise and some sort of financial incentive to continue this performance. The undercurrent to this high praise encourages all other employees to follow the successful pattern and process used by the top performer. Similarly, management may also identify employees on a wall of shame, which identifies specific people and their low performance results in an attempt to drive improvement and discourage more low performance. Poor performance can be caused by many things. However, in this example, a process expert would focus on the specific processes to determine how the as-is process is contributing to one set of performers doing well and another set doing poorly. Based on these findings, the expert may model process changes that remove variability in performance and test the new process to see if all performers can follow an improved process that drives high performance.

Another example examines how recognition can drive results. Let’s look again at the example of implementing the new CRM solution. After launching the new tool, the top sales executive reviewed the neglected accounts report and noticed that one sales person was servicing several of these neglected accounts. Within the application was a message board in which the executive asked the system administrator how he could attach a comment in order to ask the sales person to explain why he had so many neglected accounts. The executive didn’t realize that her inquiry would be visible to all users in the CRM application. Her intent was to target the communication to the individual sales person in order to drive action and to increase revenue for the company. This quest for individual accountability may have driven one of the single biggest success factors for future recognition. Within a few hours, the sales person contacted the neglected accounts, and there was an added benefit. Other accounts that were also on the list associated with other sales people were suddenly moved off the report, too. The entire sales organization had received the message and realized that the executive was watching over their performance with a critical eye, and that drove improved behavior and action. The process of servicing accounts was well defined. However, as we have been seen often in this text, attention to process performance through things like the neglected-accounts report helps shape action and bring recognition and reward.

Case Summary

Ensuring the right outcome is something of a management art. The measurements put in place at strategic points in active processes should radiate information about the performance of the process. Business intelligence information is imperative to fixing broken processes, as well as to fine-tuning processes that perform well. It is highly recommended that Six Sigma methods be used to analyze process performance and pinpoint bottlenecks and trouble spots. Analysis projects of this nature are traditionally seen as lengthy; however, when an established process-oriented architecture model is used, the assessment time can be significantly reduced. This provides valuable data that can be used to model improvement scenarios to select from and understand the downstream and upstream impacts on the business landscape.

30 Days Gets Results

The Challenge

You get the call. You know the one: “This is CxO so and so, and I need to know if we are meeting with our regulatory compliance regulations asap.”Where do you start? In this example we explore the exact situation. It occurred in early 2012 when I received a call from an executive about our company storing credit card numbers in plain text. Customers who placed orders with the company provided their credit card information via phone, email, or website. The credit information was electronically stored to help in processing customers’ order, either systematically or by the employees who handled the customer calls. The process had been in place for more than a decade before the company recognized that it was out of compliance with payment card industry (PCI) regulations. The regulation stipulated that credit data could not be displayed in plain text for employees/anyone to view in order to prevent identity theft and fraud. Because there was an unknown number of systems and places within applications that credit data could be stored, we knew we had a problem.

The Solution

Faced with a significant penalty and recognizing that the risk of identity theft had been unmanaged for more than a decade, the executive demanded that all credit data be masked to ensure no employees could see customer credit card information. The seemingly simple request created a firestorm of activity and meetings. Leaders within the order-processing business unit were familiar with the practice of storing credit card information in plain text and knew that credit card numbers were readable by hundreds of people who had access to the order-processing system. A team attempted to isolate all mechanisms that would need to be changed in order to encrypt the credit card information. However, there was confusion about just how many places the credit information could be, and that made senior leadership concerned about how long the company had been at risk of losing its customers’ credit information. Days went by. What first appeared to be complete identification of all the places that credit data appeared turned out to be inaccurate. The team was back in a room trying to calm the senior leadership’s concern by claiming that because the company had never had an incident before, their concern wasn’t warranted. The division director knew that this information was stored in dozens of places, and she reached out to the process team for help to fix the gap for good.

The Result

This was the point where the process-oriented architecture model was put in place and a solution to the problem found. In short order, the team huddled together and mapped the company’s entire order-to-cash process. There was a tremendous focus on getting everything mapped, placing the business rules and conditions out in the open, and achieving clarity on misunderstood ways in which the business had been running. Special care was taken to identify all the customer credit data and the systems that were part of the interactions. The team identified all sensitive data within one day. In doing so, the team initiated a segment of a larger process ecosystem that, over the coming months, enabled the organization to spot bottlenecks and gaps in process coverage and control and to speed up delivery simply by enabling the organization to see how things were working. The credit data were programmatically masked so that the company would be compliant with PCI legislation, and all customer information was safe and secure.

Case Summary

Not all organizations have their process landscape documented; in fact, most do not. What seems like a daunting task might actually turn out to be the single biggest competitive differentiator for a successful business. Those who recognize the need for architecting their processes are more likely to have the end result for their customer be successful and profitable. Using the process-oriented architecture framework, we suggest that you take on the toughest process issue first in order to get a baseline of the business engine. It is through steady evolution that the process landscape not only emerges but also becomes a valuable tool. In one of our most successful process transformation experiences, we plastered the walls of the head office hallway with end-to-end process maps for all to see. This generated self-correction of the maps and corresponding adjustments through governance monitoring. In doing so, the organization became abuzz with excitement about improvement opportunities, and we found ourselves engaged in high-value discussion with reenergized employees about how they could make a difference. The result was improved employee satisfaction scores and creation of the momentum necessary to achieve a culture of measurement and improvement.

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we reviewed Case examples to illustrate the value of the concepts presented in this book. Following is a summary of these examples:

• Recognize What Failure Is: The Amazon.com experience demonstrated the importance of consistency in experience through process continuity and quality.

• Achieve Customer Delight: The winter coat story revealed the expectations that can be set and met if well thought out.

• What Can Go Wrong, How To Make IT Right: This example reviewed process design with flexibility in mind.

• Remove Roadblocks: Here we identified how measures in process outcomes can trick organizations into misunderstanding the service impact to a customer by not measuring the process experience end-to-end from the customer’s perspective.

• Reward and Celebrate: This example retold the success achieved by using incentives to drive process maturity.

• 30 Days Gets Results: Here we noted how process maps and associated attributes can provide strategic value and speed to an enterprise.

Chapter Preview

To this point, we have covered principles and practical examples in which one can understand the usefulness of The Process Improvement Handbook. In the next chapter, templates and their associated instructions are presented as companion guides to help an organization build their own tool kit toward Process Improvement.