ARTS AND CRAFTS GARDENS were represented in numerous books and paintings, which were romantically attractive and widely disseminated. These images followed the lead of artists such as Helen Allingham and Kate Greenaway who romanticised the ‘rural idyll’, and the less well known, such as T. H. Hunn. The attractiveness and humanity of the results ensured their continuing popularity.

The more lavish illustrations of bursting borders showcased artists who specialised in painting gardens, including Beatrice Parsons (1870–1955), Samuel Elgood (1851–1943), and Alfred Parsons (1847–1920), and graced books and art and design periodicals. These included Elgood and Jekyll’s Some English Gardens (1904) and, from 1893, The Studio, an art and design periodical founded and edited by Charles Holme, who lived in Morris’s Red House and owned Upton Grey Manor House, Hampshire. Three editions of The Studio in 1907, 1908 and 1911 illustrated gardens throughout Britain in photographs, but these were interspersed with colour reproductions of romantic watercolours by Elgood and others, depicting the Arts and Crafts style of planting. Ernest Chadwick (1876–1955) provided a significant number of illustrations for Mawson – many being used in the fourth (1912) and fifth (1926) editions of The Art and Craft of Garden Making. Chadwick was a Birmingham artist of some renown specialising in rural scenes, landscapes and gardens.

The best garden photographs appeared in Country Life Illustrated, with high-quality and beautifully composed black-and-white shots of houses and gardens, in a glossy magazine which positively promoted the Arts and Crafts philosophy and depicted many of its newly built houses and gardens. Country Life was owned and published by Edward Hudson, a self-made man for whom Lutyens and Jekyll produced so many designs. Hudson commissioned the golden pair to create homes and gardens for himself, including the rugged and remote Lindisfarne Castle on Holy Island, Northumberland (1911), an aspiring Home Counties manor house in a former orchard at Deanery Garden, Berkshire (1899–1901), and also Plumpton Place, East Sussex.

The finest of garden photographs appeared weekly from 1897 in the ultimate in aspirational lifestyle periodicals, Country Life Illustrated. Owner and proprietor Edward Hudson lived the ideal in his four Lutyens houses, whose gardens had Jekyll planting. Deanery Garden, Berkshire.

Miss Jekyll illustrated her numerous garden books (some of which remain in print today) lavishly with photographs; most of these, including Garden Ornament (1918) and Gardens for Small Country Houses (1912), were published by Country Life. Other authors used engravings and line drawings to illustrate their manuals of design, including plantsman William Robinson (The English Flower Garden, 1883, numerous later editions and in print today), landscape architect Thomas Mawson (The Art and Craft of Garden Making), and architects Baillie Scott (Houses and Gardens, 1906), Sedding (Garden-Craft Old and New, 1891), Blomfield (The Formal Garden in England, 1892) and Godfrey (Gardens in the Making, 1914). The bird’s-eye view was especially suited to this treatment, echoing the well-known set of country house illustrations by Knyff and Kip in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Baillie Scott included colour reproductions of his own beautiful watercolours.

The bindings of garden books were finely designed and crafted in true Arts and Crafts spirit. Beatrice Parsons and E. T. Cook’s Gardens of England (1908) contains Parsons’ romantic views of gardens planted in the Arts and Crafts style.

Even the bindings of these publications were finely designed, detailed and tooled in true Arts and Crafts spirit. One of the finest is Beatrice Parsons and E. T. Cook’s Gardens of England (1908) with its beautifully coloured and tooled binding, also Scottish Gardens: Being a Representative Selection of Different Types, Old and New, written by Sir Herbert Maxwell and illustrated by Mary Wilson (1908). More modest books had illustrated bindings, including Violet Biddle’s Small Gardens (c. 1903). Even catalogues had attractively designed covers, such as John P. White’s garden furniture catalogue of the Pyghtle Works, Bedford, and Harwood of Balham’s seed catalogue.

Garden catalogues had lavishly designed covers to entice aspiring purchasers, such as John P. White’s Pyghtle Works furniture catalogue, Bedford.

Even the humble seed catalogue might be artistically covered: Harwood of Balham, 1895.

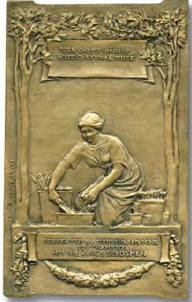

The Arts and Crafts movement and publications by its followers did much to encourage the popularity of gardening in this style as a hobby, which has continued to the present day. On 25 November 1871 William Robinson founded the weekly magazine The Garden, to which Ruskin contributed frequently and Morris occasionally. Miss Jekyll wrote numerous pieces from 1881, becoming joint editor with E. T. Cook for two years in 1900 and 1901. Ephemeral literature appeared, including manuals and catalogues. Amateur horticultural clubs for the public were founded and spawned flower shows, where gardeners could show off their horticultural prowess. Horticultural competitions needed prizes and some were of high artistic quality and craftsmanship.

Ephemeral literature was informative and helped to educate gardeners of modest means.

Some horticultural prizes were prestigious enough to warrant high artistic quality and craftsmanship. Plaque by the sculptor Hamo Thorneycroft, donated by seedsmen Toogoods, 1919.

Professional horticulture became acceptable for women. Education was necessary and several ladies’ gardening colleges appeared, such as the Glynde College for Lady Gardeners and Studley College for Ladies. Indeed, of the Glynde College it was noted in 1906 in The Bystander magazine:

Every form of gardening can be studied at Glynde; digging, hoeing, treatment of seedlings and greenhouse plants, the care of lawns, paths, and beds, in fact, every branch of the science, for the highest technical skill is required to make gardening a paying concern.

Miss Jekyll fully approved of this, being a hands-on gardener herself, and in 1907 ‘lady gardeners’ carried out her planting schemes at the recently built King Edward VII Sanatorium, a private tuberculosis sanatorium near Midhurst, West Sussex. Margaret Biddulph trained as a horticulturist at Studley College before she employed William Scrubey (whom she had met there) as head gardener at Rodmarton, where he designed the planting within Ernest Barnsley’s framework. The Women’s Farm and Garden Union was founded in 1899, of which Miss Jekyll became one of the vice-presidents in 1916.

The Gardening College, Glynde, East Sussex (founded 1902). The Bystander reported in 1906, ‘Many ladies, through necessity, have to earn their own livelihood, and one of the most attractive ways of doing so, as well as one in which the competition is not severe, is that of gardening.’