CHAPTER 1

Introduction

It is generally accepted that contract bridge started in about 1925 when Harold Sterling Vanderbilt was cruising the Caribbean on the SS Finland. He picked up a pack of cards, shuffled them, and said ‘Gentlemen, let me show you a new game. It may interest you.’

Bridge is said to be the Rolls-Royce of card games, and for good reason. It can be as comfortable as your favourite pair of shoes, and yet at the same time it can excite you as much after you have played for years as when you first experienced the game. Bridge can be a quiet source of pleasure when you play in familiar surroundings with friends you have known all your life, or a tool which introduces you to new people in new places. Tennis star Martina Navratilova once said that bridge meant a lot to her in her travels: ‘No matter where I go’, she said, ‘I can always make new friends at the bridge table’. Omar Sharif is said to have given up acting, horses and women for the game. For others, bridge is a great social activity. It is difficult to believe that bridge is good for us; to believe that something that brings so much joy is neither immoral, against the law nor bad for our health. If you are not yet familiar with the game, what have you been waiting for? If you have played for years, it’s time to introduce you to some of the secrets of the experts, taught, we hope, with a mixture of fun and simplicity.

Getting started

All you need are three other people and a pack of cards. If you have a card table, four chairs and a pencil and paper to keep score, so much the better. Already you are as well-equipped as a world champion!

Bridge is a partnership game. Although you can play with a regular partner, it is common to cut for partners. To do this, take the cards and spread them face down on the table. Each player selects a card and turns it up. The cards are ranked as usual in this order: Ace (highest), King, Queen, Jack, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2 (lowest). The players choosing the two higher-ranking cards play together and those picking the two lower-ranking cards are partners. If the four cards turned over were an ace, a king, a jack and a 3, the players choosing the ace and king would play together and the players turning over the jack and 3 would be partners.

What if two players pick the same ranked card? Let’s consider a most unusual case where all four players pick aces. It looks as if there is a four-way tie, but there is a method of breaking such a tie. The suits are ranked in alphabetical order with the clubs ( ) being the lowest ranked suit, then diamonds (

) being the lowest ranked suit, then diamonds ( ), hearts (

), hearts ( ) and, at the top, the highest ranking suit, spades (

) and, at the top, the highest ranking suit, spades ( ). In the situation mentioned above, then, the players with the ace of spades (

). In the situation mentioned above, then, the players with the ace of spades ( A) and ace of hearts (

A) and ace of hearts ( A) would play against the players holding the ace of diamonds (

A) would play against the players holding the ace of diamonds ( A) and ace of clubs (

A) and ace of clubs ( A).

A).

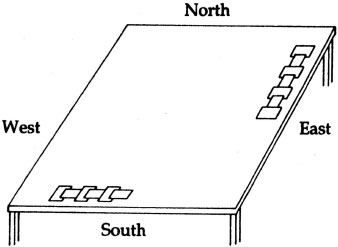

The partners sit opposite one another. Bridge writers refer to the players not by name but by direction: North, East, South and West. Here, then, are the four players sitting round the table:

Introducing the play

Once everyone is sitting down and ready to play, the player who chose the highest card deals. The jokers are not used, so a bridge pack consists of 52 cards. Starting with the player on his left, the dealer deals one card at a time to each player, proceeding clockwise around the table, until the pack is exhausted and each player has 13 cards. If, during the deal, a card is accidentally turned face up, the deal must be restarted – the pack must be shuffled and cut, and the dealer tries again! Each player picks up his hand and sorts it into suits. It is easier to see your hand if you separate the black and red suits. Here is a sorted bridge hand:

In a book or newspaper, the above bridge hand is usually written out in the ranking order of the suits, with spades first, then hearts, diamonds and clubs as follows:

The objective during the play of the hand is for your partnership to try to take as many tricks as you can. A trick consists of four cards, one from each player, and the player contributing the highest card wins the trick for his side. The player who wins each trick leads the first card to the next trick face up on the table and the other three players play their cards, in turn, clockwise around the table. Everyone has to follow suit to the first card that is led, if they can. For example, let’s suppose that West leads the king of spades. All the other players, in turn, have to follow suit by playing a spade, if they have one. Suppose North contributes the ace of spades, the highest card in the suit, East plays the 3 of spades and South plays the 2 of spades. North has won the trick for his side (North-South). Here is the trick:

North collects the four cards and puts them in a stack face down in front of himself. Usually, one member of the partnership collects all the tricks won for his side. At the end of the hand, thirteen tricks will have been played and the table might look like this:

You can see that North-South took six tricks and East-West took seven. The game can be played in one of two ways: with a trump suit, or in no trumps. In no trumps, the highest card played in the suit led always wins the trick. If you cannot follow suit, you must play a card in another suit, but a card discarded in this way has no power to win the trick, even if it is higher-ranking than the card led. To take an unlikely example: West leads the two of clubs, on which North plays the ace of spades, East the ace of hearts and South the ace of diamonds. West is the winner of the trick, for his two was the highest – indeed the only – card played in the suit led. The winner of the trick, when playing in no trumps, is the person who played the highest card in the suit that was led.

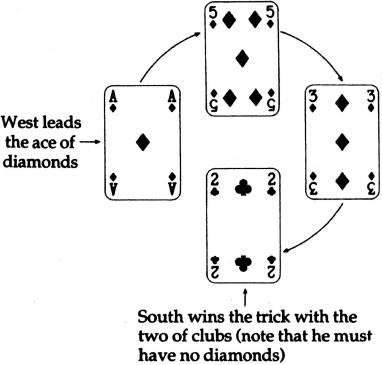

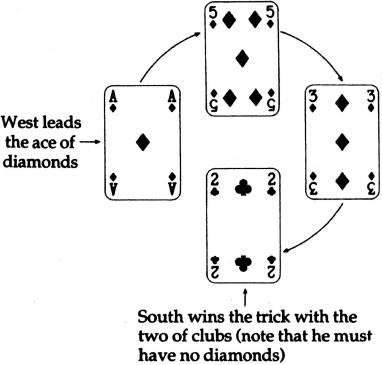

The game can also be played in a trump suit where one suit becomes the most powerful suit for that hand. If you cannot follow suit you can play a trump and it will win the trick, provided a higher trump is not played on the same trick. For example, let’s suppose that clubs have been designated as the trump suit. West leads the  A, North plays the

A, North plays the  5, East plays the

5, East plays the  3 and South plays the

3 and South plays the  2. The trick looks like this:

2. The trick looks like this:

Because clubs are trumps, the small club wins the trick. South, however, can only play the  2 if he has no diamonds left in his hand. Otherwise, he must follow suit by playing a diamond on the trick. South does not have to play a trump if he has no diamonds. Instead, he can discard a heart or spade and let West win the trick with the

2 if he has no diamonds left in his hand. Otherwise, he must follow suit by playing a diamond on the trick. South does not have to play a trump if he has no diamonds. Instead, he can discard a heart or spade and let West win the trick with the  A. It is permitted to lead trumps. If the trump suit is led, the highest trump played wins the trick. Let’s summarise all these points about playing the cards:

A. It is permitted to lead trumps. If the trump suit is led, the highest trump played wins the trick. Let’s summarise all these points about playing the cards:

Summary of play of the hand

1 You and your partner work together to take as many tricks as you can.

2 When one player leads a card to a trick, all other players must follow suit if they can. If a player cannot follow suit, he plays a card from another suit.

3 The player who wins the trick leads to the next trick. Each player follows clockwise in turn.

4 In no trumps, the highest card of the suit led wins the trick.

5 When playing with a trump suit, if a player cannot follow suit he can choose to play a trump. If more than one trump is played to a trick, the highest trump played wins the trick. This is the only exception to the cardinal rule of trick taking which is that the highest card played in the suit led always wins the trick.

Introducing the bidding

In some card games, the trump suit is decided by turning up a card, sometimes from another pack. In bridge, each player gets an opportunity to suggest that the longest suit in his hand be the trump suit. Suppose this is your hand:

Your longest suit is hearts and so you would suggest that hearts be trumps, by bidding hearts. Now let’s look at your partner’s hand:

The longest suit in your partner’s hand is spades, so that would be his first choice, or bid. The bidding is simply a conversation that you have with your partner to reach a consensus about the trump suit. One drawback is that you have to reach this decision without seeing your partner’s hand. That seems fair, doesn’t it? Can you imagine how colourless the game would be if you could look at one another’s hands? Another limitation is that you cannot mention the actual cards that you hold in a suit or the number of cards that you hold in each suit. It would take away the challenge if you could say to your partner that you have the ace, king, 7, 5 and 2 of hearts or that you have a four-card club suit headed by the ace and king.

Instead, the type of conversation you and your partner could have with the above hands would, possibly, go something like this:

|

You:

|

I like hearts better than any other suit.

|

|

Partner:

|

I like spades best; I don’t have many hearts.

|

|

You:

|

I don’t like spades very much but what do you think about clubs?

|

|

Partner:

|

I don’t mind clubs.

|

|

You:

|

So let’s agree to choose clubs as our trump suit.

|

|

Partner:

|

Seems reasonable.

|

This is the concept of bidding. It really is this simple, except for a very small catch we will come to shortly. You and your partner are having a conversation to tell each other as much as possible about your hands. How did you and your partner do in the above discussion? You found your longest combined suit, which is the idea of bidding. In either hearts or spades, on these hands, you have only seven combined cards in the suit. In clubs you and your partner have an eight-card fit, which means you have eight cards in the suit between the two hands. No matter how far you go in bridge, bidding should never be more complicated than the concept of a conversation between two friends.

The partnership, through the bidding, tries to uncover the suit in which it holds the most cards – the suit that would make the best trump suit. A good trump suit is usually one containing eight or more cards between the two hands. Since there are thirteen cards in a suit, if your side has eight, the opponents have only five cards and you hold the clear majority of the suit. If you can make your longest combined suit the trump suit, you will be able to use your small trump cards to help win tricks whenever you cannot follow suit, since they will then have more value than even the ace in a suit that is not trumps.

Now, about that catch! Let’s take another look at the bidding. When you play a game of bridge, you are expected to use only the language and the vocabulary of the game. You cannot actually say ‘I like hearts, how about you?’ The good news, however, is that the bridge language is spoken world-wide and the vocabulary consists of only a handful of words: the numbers from one to seven; the names of the suits – clubs, diamonds, hearts and spades – or no trumps; and the words pass or no bid. These few simple words are all you need to describe your hand.

A bid is a combination of a number and a denomination (a suit or no trumps). A bid, for example, would be one heart (1 ), three spades (3

), three spades (3 ), six no trumps (6NT) or seven clubs (7

), six no trumps (6NT) or seven clubs (7 ). You can envisage that, if you say one heart (1

). You can envisage that, if you say one heart (1 ), it means you like hearts. The number refers to the number of tricks you are expected to take if you win the bid. One heart, however, does not refer to taking only one trick with hearts as trumps. Six tricks, referred to as your book, must be added to the number of the bid. If you say ‘one heart’, you and your partner would have to take seven (6 + 1 = 7) tricks if your bid for the trump suit is accepted. The idea behind this assumed book of six tricks in addition to the number that you actually bid is that you must commit yourselves to taking the majority of the thirteen tricks available if you want your suit to be the trump suit.

), it means you like hearts. The number refers to the number of tricks you are expected to take if you win the bid. One heart, however, does not refer to taking only one trick with hearts as trumps. Six tricks, referred to as your book, must be added to the number of the bid. If you say ‘one heart’, you and your partner would have to take seven (6 + 1 = 7) tricks if your bid for the trump suit is accepted. The idea behind this assumed book of six tricks in addition to the number that you actually bid is that you must commit yourselves to taking the majority of the thirteen tricks available if you want your suit to be the trump suit.

Bridge bidding is like an auction. The players try to outbid each other for the privilege of naming the trump suit. There is no auctioneer, however. Instead there is an agreed-upon, orderly way of conducting the bidding.

The dealer gets the first opportunity to open the bidding by suggesting a denomination (a trump suit or no trumps). If he does not want to commit his side to trying to take at least seven tricks – the minimum requirement for opening the bidding – he can say ‘Pass’ or ‘No bid’. Each player, clockwise in turn, then gets a chance to make a bid or to pass. The auction continues round the table until a bid is followed by three passes, meaning that everyone is in agreement with the last bid, and no one wants to bid any further.

What if one player bids 1 and the next player wants to bid 1

and the next player wants to bid 1 ? Which bid is higher? There is an automatic tie-breaker built into the language of bridge. The suits are ranked, remember, in ascending alphabetical order (clubs, diamonds, hearts, spades). No trumps is considered to rank the highest of all, higher than spades. Since diamonds are lower-ranking than spades, a 1

? Which bid is higher? There is an automatic tie-breaker built into the language of bridge. The suits are ranked, remember, in ascending alphabetical order (clubs, diamonds, hearts, spades). No trumps is considered to rank the highest of all, higher than spades. Since diamonds are lower-ranking than spades, a 1 bid outranks a 1

bid outranks a 1 bid. If the next player wants to suggest diamonds as the trump suit, he will have to commit his side to taking more tricks by raising the level and bidding 2

bid. If the next player wants to suggest diamonds as the trump suit, he will have to commit his side to taking more tricks by raising the level and bidding 2 . On the other hand, if the next player wants to suggest no trumps, he can bid 1NT, since that outranks the 1

. On the other hand, if the next player wants to suggest no trumps, he can bid 1NT, since that outranks the 1 bid.

bid.

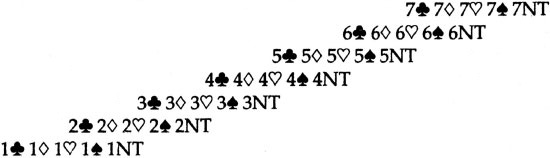

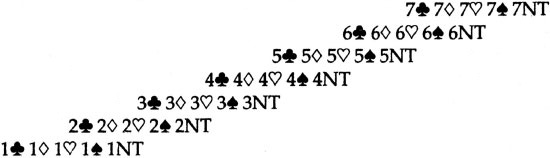

We can think of the possible bids as a series of steps leading from one level to the next as illustrated below:

The bidding steps

Each bid must be further up or further to the right on the bidding steps than the preceding bid. If a player starts the bidding at the one level (1 , 1

, 1 , 1

, 1 , 1

, 1 or 1NT), contracting to take seven tricks, another player can make a bid in a higher-ranking denomination at the one level or must climb to the two level, contracting to take eight tricks, if he wants to make a bid in a lower-ranking denomination. If a player does not want to bid any higher, he will pass.

or 1NT), contracting to take seven tricks, another player can make a bid in a higher-ranking denomination at the one level or must climb to the two level, contracting to take eight tricks, if he wants to make a bid in a lower-ranking denomination. If a player does not want to bid any higher, he will pass.

Hearts and spades are referred to as the major suits and, when you look at the bidding steps, you can see they are higher-ranking than clubs or diamonds which are referred to as the minor suits.

After there are three passes, the last bid determines the trump suit and the number of tricks that the side naming this trump suit must take to be successful. The final bid becomes the contract. Let’s look at our two hands to see how they would be bid using the language of bridge. We will assume that the opponents do not wish to compete for the contract and choose to pass throughout the auction.

|

You

|

Partner

|

|

3 2 3 2

|

A 8 6 5 4 A 8 6 5 4

|

|

A K 7 5 2 A K 7 5 2

|

6 6

|

|

7 3 7 3

|

9 6 2 9 6 2

|

|

A K 7 3 A K 7 3

|

Q J 8 6 Q J 8 6

|

|

You:

|

One heart.

|

(I like hearts and am contracting to take seven tricks with hearts as trumps.)

|

|

Partner:

|

One spade.

|

(I would prefer spades as trumps. I can keep the bidding at the one level since spades rank higher than hearts.)

|

|

You

|

Two clubs.

|

(You don’t seem to like my hearts. How about clubs? I have to move to the two level to show my second suit since clubs are lower-ranking than spades.)

|

|

Partner:

|

Pass

|

(I like clubs much better than hearts and they should make a satisfactory trump suit. I do not want to go any higher up the bidding steps since we are already contracting to take eight tricks.)

|

Let’s suppose you are sitting in the South position and your partner is North. This is the way the above auction would normally be written down, showing your opponents’ passes as well as your bids:

|

South

|

West

|

North

|

East

|

|

1

|

Pass

|

1

|

Pass

|

|

2

|

Pass

|

Pass

|

Pass

|

West, North and East all have to say pass after the 2 bid in order to end the auction. North-South are said to have won the bid and the final contract is 2

bid in order to end the auction. North-South are said to have won the bid and the final contract is 2 . What happens next?

. What happens next?

Introducing the roles of each side

After the bidding is completed, one partnership has been successful in naming the trump suit and, in the process, has arrived at a contract, which is a commitment to take a certain number of tricks. In the example above, North-South arrived at a contract of 2 and, in doing so, committed to take eight tricks with clubs as trumps. If they take at least eight tricks with clubs as trump, they make their contract. If they are not successful in collecting eight tricks, then East-West defeat the contract. East-West are said to be the defence and they are trying to prevent North-South from taking enough tricks to fulfil the contract.

and, in doing so, committed to take eight tricks with clubs as trumps. If they take at least eight tricks with clubs as trump, they make their contract. If they are not successful in collecting eight tricks, then East-West defeat the contract. East-West are said to be the defence and they are trying to prevent North-South from taking enough tricks to fulfil the contract.

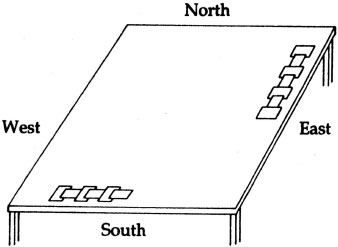

One player from the side who wins the contract is called the declarer and that player is going to play both his and his partner’s hands. The other hand is referred to as the dummy. Which player is the declarer and which player is the dummy? The player who first mentioned the suit that ended up being the trump suit (or whoever bid no trumps first in a no-trump contract is the declarer and his partner becomes the dummy. In the auction above, South is the declarer since he was the first to mention the club suit and his partner, North, is the dummy. The player to the left of the declarer makes the opening lead. In this case, it would be West and he would choose a card and place it on the table. North’s hand, the dummy, is then placed face up on the table. The trump suit is put on dummy’s right – the declarer’s left. Suppose the opening lead is the  K. After the dummy is put down, the cards on the table might look like this:

K. After the dummy is put down, the cards on the table might look like this:

In order to discuss the play from the declarer’s viewpoint, the hand is usually illustrated as follows:

The defenders (East-West) can take the first two diamond tricks but you can trump the third round of diamonds with one of your clubs. This is one of the advantages of playing this hand with clubs as the trump suit. It prevents the opponents from taking too many tricks with their diamond suit. You will learn how to play this hand as you read through the first part on declarer play.

Introducing the scoring

In the above hand, when you take the eight tricks to which you committed yourself in the auction, you are awarded a certain number of points for fulfilling the contract. The exact details of the scoring are contained in the appendix. All that is important for now is that you have a general idea of how the game is scored. The partnership which earns the highest number of points from all the hands that are played wins the game. Points can be scored in three ways:

• If you make (fulfil) your contract, you are given a trick score for each trick you take beyond your book of six tricks.

• If you defeat the opponents’ contract, by preventing them from taking the number of tricks to which they committed themselves, you gain points for each trick by which you defeat their contract. In effect, your opponents suffer a penalty when they go down (are defeated) in their contract.

• Points are awarded for reaching and making certain bonus level contracts.

Summary

The four players form two partnerships, with the partners sitting opposite each other across the table.

After the cards have been dealt out, the players, in clockwise rotation starting with the dealer, have an opportunity to suggest the denomination (trump suit or no trumps) in which they would like to play the hand.

Each bid must be higher on the bidding steps than the previous bid. If a player does not want to bid, he says pass or no bid.*

The side willing to commit itself to the greater number of tricks for the privilege of naming the denomination wins the auction.

The last bid becomes the final contract.

The player who first suggested the denomination of the final contract becomes the declarer and his partner becomes the dummy.

The defender to the left of the declarer leads to the first trick and then the dummy’s hand is placed face up on the table.

The declarer tries to take the number of tricks his side committed itself to in bidding the final contract. He plays the cards from both the dummy and his own hand on each trick.

The defenders try to take enough tricks to defeat the contract.

With this introduction, you are ready to play.

* Pass is commonly used in the USA, ‘no bid’ in Britain, but either is correct

) being the lowest ranked suit, then diamonds (

) being the lowest ranked suit, then diamonds ( ), hearts (

), hearts ( ) and, at the top, the highest ranking suit, spades (

) and, at the top, the highest ranking suit, spades ( ). In the situation mentioned above, then, the players with the ace of spades (

). In the situation mentioned above, then, the players with the ace of spades ( A) and ace of hearts (

A) and ace of hearts ( A) would play against the players holding the ace of diamonds (

A) would play against the players holding the ace of diamonds ( A) and ace of clubs (

A) and ace of clubs ( A).

A).