, for example, you are telling your partner that hearts is your longest suit – ‘I like hearts’.

, for example, you are telling your partner that hearts is your longest suit – ‘I like hearts’.CHAPTER 2

Hand Valuation

The new game, contract bridge, not only interested those in the ship’s stateroom, it caught the imagination of people around the world. The media caught the ‘bridge bug’ and bridge became front page news. The game became a popular pastime, with both men and women. Housewives, who had hitherto thought a dummy was a baby’s pacifier, banded themselves together to the permanent ruin of their husbands’ digestion.

Well, you are about to learn a foreign language. If you have ever tried this before, you know how difficult it can be – which is the bad news. The good news about learning the language of bridge is that the vocabulary consists of only a few words. The more fluent you become in using this new language, the better bidder you become. All you need to do is remember that the sole purpose of bidding is to describe the cards in your hand as clearly as possible to your partner, using the language of bridge. Using only two words – ‘one spade’, for example – you paint a picture of your hand. If you ever wanted to be a person of few words, bridge provides the opportunity!

Valuing a hand

A bid portrays something about both the distribution and strength of your hand. The distribution is the number of cards you hold in each suit. As we saw in the sample auction in Chapter 1, you start to describe your distribution through the denomination of your bid. If you open the bidding 1 , for example, you are telling your partner that hearts is your longest suit – ‘I like hearts’.

, for example, you are telling your partner that hearts is your longest suit – ‘I like hearts’.

High card points

Before you can make a bid that starts to describe your distribution to your partner, however, you must have sufficient strength (trick-taking power) to enter the auction. After all, every time you make a bid you are committing your side to take a certain number of tricks. Since most tricks are taken with the high cards in each suit – aces, kings, queens and jacks – an estimate of the strength of your hand can be arrived at by giving a value to each of the high cards in your hand. Since the ace is the most valuable card in a suit, followed by the king, queen and jack, the following scale is used:

High card points

|

Ace |

4 points |

|

King |

3 points |

|

Queen |

2 points |

|

Jack |

1 point |

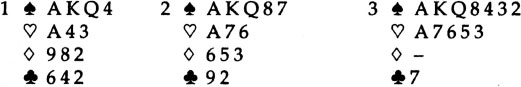

You add up the high card points (HCPs) for each of the high cards in your hand to arrive at a total value. For example, what do the following three hands have in common?

They each contain 13 high card points (HCPs) – 4 for the  A, 3 for the

A, 3 for the  K, 2 for the

K, 2 for the  Q and 4 for the

Q and 4 for the  A. That was easy; you are already halfway to becoming a bridge player.

A. That was easy; you are already halfway to becoming a bridge player.

Although all the hands contain exactly the same high cards, however, are they all of equal value? Which hand would you most like to have? If you chose the third hand, go to the top of the class! The trick-taking potential of the third hand is increased because of the long suits. If, for example, you can make spades the trump suit, you will take a lot of tricks with your small spades, in addition to the  A,

A,  K and

K and  Q. Likewise, the second hand is more valuable than the first. The total strength of a hand, therefore, is a combination of the strength and the length (distribution) of your suits.

Q. Likewise, the second hand is more valuable than the first. The total strength of a hand, therefore, is a combination of the strength and the length (distribution) of your suits.

Support points

When you are the dealer and have the first opportunity either to open the bidding or pass, you have no information about your partner’s hand. Sometimes your partner is the dealer and you hear your partner’s suggestion before you have to give your opinion. Consider this hand:

How would you feel about your hand if your partner opened the bidding 1 ? Compare this with the way you would feel if your partner opened 1

? Compare this with the way you would feel if your partner opened 1 . Most of us would feel that this particular hand is more valuable if our partner opens 1

. Most of us would feel that this particular hand is more valuable if our partner opens 1 since we can see that hearts would make a much more suitable trump suit than spades. To reflect the increased value of a hand in this type of situation, we use support points.

since we can see that hearts would make a much more suitable trump suit than spades. To reflect the increased value of a hand in this type of situation, we use support points.

Support points are used when you are expecting to be the dummy, that is, when you are going to support (agree as trumps) your partner’s suit. With the above hand, if your partner opens 1 , you are not planning to support his suit. On the other hand, if partner opens the bidding 1

, you are not planning to support his suit. On the other hand, if partner opens the bidding 1 , you want to agree to that suit as trumps. When you support your partner, you value your short suits: voids (no cards in a suit), singletons (one card in a suit) and doubletons (two cards in a suit) using the following scale:

, you want to agree to that suit as trumps. When you support your partner, you value your short suits: voids (no cards in a suit), singletons (one card in a suit) and doubletons (two cards in a suit) using the following scale:

|

Void |

5 points |

|

Singleton |

3 points |

|

Doubleton |

1 point |

In the above hand, then, if your partner opens 1 , give yourself 8 HCPs and 5 points for the void in spades, for a total of 13 points. On the other hand, if your partner opens 1

, give yourself 8 HCPs and 5 points for the void in spades, for a total of 13 points. On the other hand, if your partner opens 1 , you would not be supporting his suit so the hand would be worth only 8 points.

, you would not be supporting his suit so the hand would be worth only 8 points.

You can see from this that the value of your hand can change dramatically during the auction. To start with, before any player has made a bid, your hand is worth 9 points as explained. When your partner opens the bidding in spades, your hand is still worth only 9 points. But suppose you make a bid – we will see exactly what bid you might choose later, but say for the moment that you bid two diamonds – and your partner now bids two hearts. All of a sudden, your hand has become worth 13 points, because of the extra support points that you have if hearts are going to be trumps. It is the hallmark of the expert bidder that he can make mental adjustments to the initial value of his hand as the auction progresses.

Determining the hand pattern

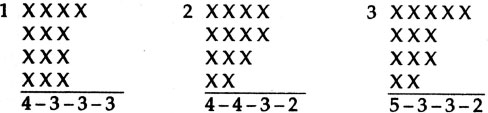

In addition to focusing on the strength of your hand, you also want to take a look at the distribution or the shape. The fundamental thing to remember whenever you look at a hand is: does it belong to the family of balanced hands or the family of unbalanced hands? There is a strong family resemblance among balanced hands. There are no voids, no singletons and no more than one doubleton. It is a small family and has only three members:

The numbers under each pattern refer to the number of cards in the four suits. For example, in the first hand, there are four cards in one suit and three in the other three suits (4–3–3–3). In the second hand, there are two four-card suits, a three-card suit and a doubleton (4–4–3–2). In the final pattern, there is a five-card suit, two three-card suits and a doubleton (5–3–3–2).

All other hand patterns are unbalanced. The possible combinations are now far greater. In an extreme case, a member of the unbalanced family of hands could have three voids and a thirteen-card suit. Here are three members of the unbalanced family:

The first hand qualifies as unbalanced because it has a void; the second because there are two doubletons; the third because there is a singleton.

Now that you are able to calculate the value of your hand and recognise its shape, you are ready to open the bidding.

Summary

Before you decide what to bid, value your hand using the following guidelines:

Hand value

High card points

|

Ace |

4 points |

|

King |

3 points |

|

Queen |

2 points |

|

Jack |

1 point |

Next, look at the shape of your hand and decide whether it is a member of the balanced or unbalanced family.

Hand families

|

Balanced |

Unbalanced |

|

• No void |

• Could have a void |

|

• No singleton |

• Could have a singleton |

|

• No more than one doubleton |

• Could have more than one doubleton |

If your partner has bid and you are planning to support the suit he bid, use support points, rather than length points, to value your hand.

|

Void |

5 points |

|

Singleton |

3 points |

|

Doubleton |

1 point |

Commonly asked questions

|

Zia: |

Audrey, you work with a lot of students. What are some of the questions they most frequently ask? |

|

Audrey: |

Most of the questions at this point are about different methods of doing things which they have come across from other sources, such as books, newspapers, friends, relatives and even your television show, Zia. For example, they might wonder about giving points for length rather than shortness and whether they can play with a partner who values his hand by giving points for a void, a singleton or a doubleton when making an opening bid. They ask about valuing high cards in short suits – a singleton ace or king, a doubleton queen or jack. |

|

Zia: |

Our answer, of course, would be to keep it simple. |

|

Audrey: |

That’s right. There is no need to memorise a lot of material which you will rarely encounter. At the end of each chapter, we’ll include a section on the most frequently asked questions – along with the answers, of course. |