CHAPTER 29

Establishing Small Cards

Remember at the bridge table you want, to meet old friends and make new ones ... not lose friends.

There are five honours in each suit – the ace, king, queen, jack and ten – and eight small cards – the nine down to the two. It is not often that the defenders have enough combined strength to defeat the contract with their high cards alone. It is important to remember, however, that a small card can have the same power as an honour if it can be established as a winner. This is especially valuable in a no-trump contract, since the declarer will have no trump suit to prevent you from taking a winner once it is established. Let’s consider how you can defend by making the best use of the small cards.

Establishing tricks in long suits

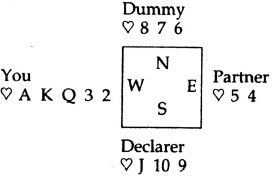

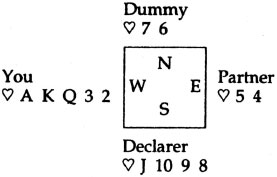

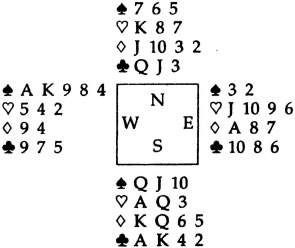

Consider the layout of the following suit:

You initially have only three sure tricks, the  A, the

A, the  K and the

K and the  Q. After you have played the suit three times, however, none of the other players has any hearts left. If the contract is in no trumps, you can now take two more tricks, the

Q. After you have played the suit three times, however, none of the other players has any hearts left. If the contract is in no trumps, you can now take two more tricks, the  3 and the lowly

3 and the lowly  2. The small cards in your long suit have become established as winners.

2. The small cards in your long suit have become established as winners.

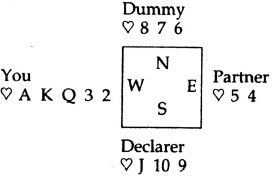

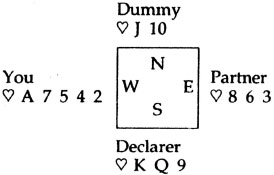

As we have seen in previous chapters, the high cards do not all have to be in the same hand for the defenders to have the opportunity to establish their small cards. Look at this layout:

The situation is virtually identical. This time, however, you will have to start by leading a small card to your partner’s  K and he can then return his small card back to your winners. We have seen in earlier chapters that leading a small heart from your holding is not unusual. It is the same thing you have to do when taking sure tricks or promoting winners, in order to get the high card played from the short side first.

K and he can then return his small card back to your winners. We have seen in earlier chapters that leading a small heart from your holding is not unusual. It is the same thing you have to do when taking sure tricks or promoting winners, in order to get the high card played from the short side first.

Giving up the lead

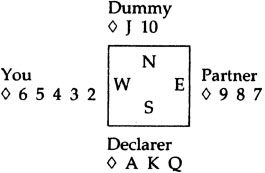

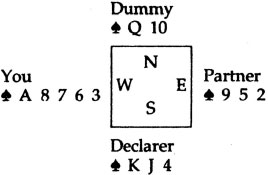

You do not necessarily need any high cards in a suit in order to develop tricks through length. Look at this example:

Although the declarer has all the honours in the suit, you can still develop two winners in the suit by leading it three times. Each time you lead the suit, one of the declarer’s high cards disappears until, finally, no one has any diamonds left and your remaining two diamonds are winners.

To develop winners in this manner takes some patience and some luck. You must keep leading the suit at every opportunity. You must also be fortunate enough to have high cards in other suits with which to regain the lead each time you give it up. You don’t always have to do all the work by yourself. If your partner has high cards in other suits he can help you out by leading diamonds every time he gets the opportunity to lead.

The moral, however, is not to be afraid to give up the lead if it will get you where you want to be. The declarer will frequently have to give you back the lead. Don’t forget that the declarer is also trying to develop the tricks he needs and this will occasionally involve losing the lead to the defenders.

Considering the division of the missing cards

How many tricks can you expect to get from your small cards? That depends on how the missing cards are divided among the remaining hands. Suppose we return to an earlier example:

In this layout, you end up with five tricks – two from small cards – because the opponents’ hearts are divided 3–3 (three in one hand, three in the other). Suppose we change the layout slightly:

With the opponents’ hearts divided 4–2, you can only take the first three sure tricks before the declarer will have a winner left in the suit. You can still establish one trick through length by leading the suit again to drive out the declarer’s winner. Now, let’s change the distribution a bit more:

If this is the layout of the heart suit, you never get more than your three sure tricks. You cannot get any tricks with your small cards.

In general, what can you expect? Will the missing cards be divided as they are in the first case, the second, or the third? You would like to have some idea of what to expect so that you will know whether or not there is a reasonable chance of developing the tricks you need from a particular suit.

If you know how many cards the opponents hold in a suit, you can determine their most likely division using the following chart:

Expected Division of Opponents’ Cards

|

Number of cards held |

Most likely distribution |

|

3 |

2-1 |

|

4 |

3-1 |

|

5 |

3-2 |

|

6 |

4-2 |

|

7 |

4-3 |

|

8 |

5-3 |

You don’t need to memorize the chart. It is enough to notice the general concept: an even number of cards tend to divide unevenly, an uneven number of cards tend to divide evenly.

It is much more straightforward for a declarer to make use of such a chart than for a defender. After all, a declarer can see both his hand and the dummy. A defender will usually be uncertain how many cards his partner has in a suit and will, therefore, be uncertain how many cards are held by the opponents.

On the other hand, a defender sometimes has an advantage over a declarer in this respect. If he can determine how many cards his partner has, he can determine exactly how many cards the declarer has by looking at the number of cards in the dummy. Sometimes, you can get a clue from the auction to how many cards your partner has in a suit. Later, when you look at the chapter on signals, you will see how the defenders can sometimes tell each other exactly how many cards they have in a suit.

Knowing about the likely division of the missing cards can help you decide which suit to lead when you have a choice. Suppose the auction proceeds as follows:

|

North |

East |

South |

West (You) |

|

1NT |

Pass |

||

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

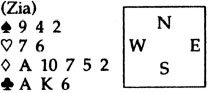

After this uninformative auction, you find yourself on lead with the following hand:

With only two sure tricks, you are going to have to find three extra tricks from somewhere. It looks as though both the spade suit and the heart suit have some potential for developing extra tricks through length, but which suit should you lead? Here is where you can put your imagination to work. You cannot see your partner’s hand so you are going to have to visualize what he might hold. Let’s make a reasonable assumption that he holds three or four small cards in both suits. Now, which suit presents the better potential?

If your partner has three spades, the opponents have six spades between them. The most likely division is for an even number of missing cards to divide unevenly, 4-2, so one of the opponents is likely to have four spades. This makes it unlikely that you can get an extra trick through length. Even if your partner has four spades, there is only potential for one extra trick through length.

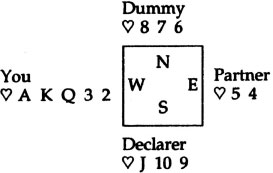

Turning our attention to the heart suit, the potential for extra tricks through length is much better. Now, even if your partner has only three small cards, there is a good chance for two extra tricks in the suit. The complete layout of the suit might look something like this:

You have one sure trick and, by leading the suit twice more, can develop two extra tricks from length.

The conclusion is that the longer the suit, the more potential for developing tricks through length. Given two suits of equal strength, you should lead your longer suit if you are planning to develop tricks from length. This applies most often when you are defending against a no-trump contract. Against a suit contract, developing extra winners in a long suit is often not very useful, since the declarer will be able to trump them.

Getting to your winners

In order to enjoy the winners you have developed in a suit, you have to regain the lead so that you can take them. You need an entry to your winners. One reason why established small cards sometimes do not end up taking tricks is that they become stranded – the defender who has the entry is not the defender who holds the winners. How can the defenders avoid this problem?

Once again, the answer lies in using a lot of imagination. Let’s suppose you are on lead with the following hand against a contract of 3NT:

In making your plan, you know that your side has to take five tricks in order to defeat the contract. You have only one sure trick, the  A. Somehow, your side has to take four more tricks. Where can they come from? You are not sure how the missing spades are divided but, if you assume that your partner has three and that the opponents’ cards are divided 3–2, you could end up with two winners from your small cards after the suit has been played three times. That’s fine, but in order to make use of these winners you have to be able to get to them. Let’s suppose that this is the layout of the spade suit:

A. Somehow, your side has to take four more tricks. Where can they come from? You are not sure how the missing spades are divided but, if you assume that your partner has three and that the opponents’ cards are divided 3–2, you could end up with two winners from your small cards after the suit has been played three times. That’s fine, but in order to make use of these winners you have to be able to get to them. Let’s suppose that this is the layout of the spade suit:

To establish your small cards as winners, the suit will have to be played three times. Suppose you start off by leading the  A and another spade. The declarer will win the second trick and go about his business. If he has to give up a trick to East, your partner can lead another spade to drive out the declarer’s last spade and establish your two remaining spades as winners. But they are stranded. You have no entry with which to regain the lead. Even if your partner manages to regain the lead, he has no spades left to lead to your winners.

A and another spade. The declarer will win the second trick and go about his business. If he has to give up a trick to East, your partner can lead another spade to drive out the declarer’s last spade and establish your two remaining spades as winners. But they are stranded. You have no entry with which to regain the lead. Even if your partner manages to regain the lead, he has no spades left to lead to your winners.

To get round this problem you must start by leading a low spade, giving the first trick up to the opponents. If your partner wins a trick and leads another spade, you still must not take your  A. Instead, you must duck – let the opponents win a trick which you could have won. Now the situation is completely different. If your partner regains the lead, he still has a spade left to lead to your

A. Instead, you must duck – let the opponents win a trick which you could have won. Now the situation is completely different. If your partner regains the lead, he still has a spade left to lead to your  A. Your small cards are established and you can take your winners.

A. Your small cards are established and you can take your winners.

You have preserved your  A as an entry to your winners. Essentially, you have merely changed the order in which you gave up the spade tricks. Instead of playing the

A as an entry to your winners. Essentially, you have merely changed the order in which you gave up the spade tricks. Instead of playing the  A and then giving up two spade tricks, you have given up two spade tricks and then taken the

A and then giving up two spade tricks, you have given up two spade tricks and then taken the  A. This little change in order makes all the difference. As a defender, you should keep the following principle in mind: if you have to lose one or more tricks to the declarer when establishing long cards in a suit, it is usually best to lose the tricks as early as possible.

A. This little change in order makes all the difference. As a defender, you should keep the following principle in mind: if you have to lose one or more tricks to the declarer when establishing long cards in a suit, it is usually best to lose the tricks as early as possible.

Let’s see how this principle can be applied when the auction has proceeded:

|

North |

East |

South |

West (You) |

|

2NT |

Pass |

||

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

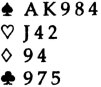

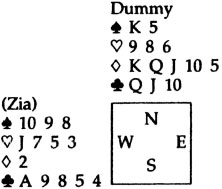

and you have to lead with the following hand:

With only two sure tricks, the best hope for developing additional tricks appears to be in the spade suit. Your partner could hold the  Q, or may hold some length. In either case, you can give your side the best chance to defeat the contract by leading a small spade. If your partner has the

Q, or may hold some length. In either case, you can give your side the best chance to defeat the contract by leading a small spade. If your partner has the  Q, so much the better. If not, you are losing the trick you have to lose as early as possible. Here is the complete hand:

Q, so much the better. If not, you are losing the trick you have to lose as early as possible. Here is the complete hand:

Contract: 3NT

Your partner has a rather disappointing holding in the spade suit and, when you lead a small spade, the declarer can win the first trick with the  10. All is not over, however. The declarer, needing to establish winners in the diamond suit, leads a diamond and your partner takes the trick with the

10. All is not over, however. The declarer, needing to establish winners in the diamond suit, leads a diamond and your partner takes the trick with the  A. He has a spade left to lead back and you can take the

A. He has a spade left to lead back and you can take the  A and

A and  K. No one else has any spades left and you can now take your remaining two small spades to defeat the contract.

K. No one else has any spades left and you can now take your remaining two small spades to defeat the contract.

What if you had started off by leading the  A and

A and  K? You could still establish your remaining small spades as winners by leading the suit again, but it would not do you any good. When the declarer leads a diamond and your partner takes his

K? You could still establish your remaining small spades as winners by leading the suit again, but it would not do you any good. When the declarer leads a diamond and your partner takes his  A, your partner has no spade left to lead back to you. You have no entry left to your hand. Whatever suit your partner leads, the declarer can win and take the rest of the tricks, making the contract.

A, your partner has no spade left to lead back to you. You have no entry left to your hand. Whatever suit your partner leads, the declarer can win and take the rest of the tricks, making the contract.

Summary

When you are looking for ways to develop the additional winners needed to defeat a contract, consider the possibility of developing winners from the small cards in your long suits. The longer your suit, the more potential for developing winners.

When developing cards in long suits, always consider the division of the missing cards in the opponents’ hands. In general, an odd number of missing cards will tend to divide as evenly as possible and an even number of missing cards will tend to divide unevenly. For example, five missing cards will tend to be divided 3-2, rather than 4-1 or 5-0; six missing cards will tend to be divided 4-2, rather than 3-3, 5-1 or 6-0.

You will usually have to give up tricks to the declarer in order to establish your small cards in a suit. Consider how you are going to get to your winners once they are established. You will need an entry. If you have to give up tricks to the declarer, it is usually best to lose the tricks as early as possible, holding on to your high cards as entries.

Over Zia’s shoulder

Hand 1 Dealer: South

|

North |

East |

South |

West (Zia) |

|

1NT |

Pass |

||

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

I can see three sure tricks against the opponents’ 3NT contract. Where are tricks four and five going to come from?

Solution to Hand 1:

Contract: 3NT

|

S |

Stop to consider the goal. We need five tricks to defeat the 3NT contract. |

|

T |

Tally the winners. We have one sure trick in diamonds and two in clubs. |

|

O |

Organize the plan. We are going to have to find two more winners. Although our high cards in clubs are attractive, our long diamond suit offers the better potential to develop tricks from length, without too much help from our partner. I think we should start by leading a small diamond. |

|

P |

Put the plan into operation. On the actual layout, the declarer wins the first diamond trick and, needing to develop some club tricks make the contract, leads a club. We win the club trick and lead diamonds again. Holding the |

Notice how important it was to keep our  A and

A and  K as entries. If we had taken them early, we would be doing the declarer’s work for him – establishing winners in the club suit. Instead, we go about our business of setting up some extra diamond winners.

K as entries. If we had taken them early, we would be doing the declarer’s work for him – establishing winners in the club suit. Instead, we go about our business of setting up some extra diamond winners.

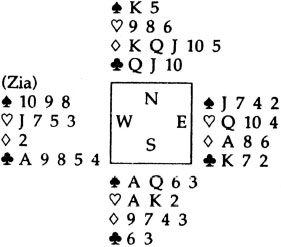

Hand 2 Dealer: East

|

North |

East |

South |

West (Zia) |

|

Pass |

1NT |

Pass |

|

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

After making my plan, I decide to lead a small club, hoping to develop some extra tricks in my club suit from the small cards. Of course, I’ll need a little help from my partner ... but that is what partners are for! After I lead a club, the dummy comes down and my partner wins the first trick with the  K and, being a good partner, returns my suit by leading another club. Well, now I can see two sure tricks for the defence but it looks as though the dummy is going to get a club trick. Where are the rest of our tricks going to come from?

K and, being a good partner, returns my suit by leading another club. Well, now I can see two sure tricks for the defence but it looks as though the dummy is going to get a club trick. Where are the rest of our tricks going to come from?

Solution to Hand 2:

Contract: 3NT

|

S |

Stop to consider the goal. We need five sure tricks to defeat the 3NT contract. |

|

T |

Tally the winners. We have only one sure trick, the |

|

O |

Organize the plan. Looking at my hand, the best chance to develop extra tricks appears to be in the club suit. Since I have five clubs, I may be able to develop some tricks through length if my partner has three or four clubs. |

|

P |

Put the plan into operation. Putting our plan into action, I lead a small club and my partner wins the first trick with the |

We needed a little luck to defeat the contract – my partner held the  A and three clubs. But, without our careful play, we would have had no chance at all.

A and three clubs. But, without our careful play, we would have had no chance at all.