North

East

South

West

(You)

1

Pass

1

Pass

2

Pass

2NT

Pass

3NT

Pass

Pass

Pass

CHAPTER 31

The Opening Lead against No-Trumps

Bridge is a sport that you can start as a child and be playing with as much enthusiasm and skill when you are ninety.

Now that we have seen some of the ways in which the defenders can get tricks, it is time to turn our attention to the specific task of selecting an opening lead. The opening lead must be chosen before the dummy is seen, reducing the amount of information the defender has available. Once the opening lead has been made and dummy has gone down, the defenders are in a better position to make a complete plan for defeating the contract.

For this reason, we sometimes modify our STOP mnemonic to think in these terms when we are making an opening lead:

|

S |

– stop to review the bidding |

|

T |

– think about the best lead |

|

O |

– organize your plan |

|

P |

– put your plan into operation |

In this chapter, we’ll use this approach to see how we go about selecting the best lead against a no-trump contract. In a later chapter, we’ll look at the differences when we have to make the opening lead against a suit contract.

Reviewing the bidding

Before choosing your opening lead, you should always STOP and review the bidding. It is amazing how much information about the other players’ hands you can get from the auction, even before you see the dummy. Taking the time to try to visualize the hands will help you throughout the defence. As you see more and more cards, you can update your mental picture until it is as though you are seeing through the backs of the hidden cards.

For example, if one of the other players has bid a suit during the auction, he will usually have at least four cards in the suit. If your partner has overcalled in a suit, you can expect him to have at least five cards in the suit. If an opponent has bid and rebid a suit, without support from his partner, he will have at least a five-card suit and probably more. If his partner fails to support the suit, especially in the case of a major suit, it is probably because he has only one or two cards in the suit. If a player describes a balanced hand, perhaps by opening or rebidding in no trumps, you can be certain that he has no singletons or voids, and probably only one doubleton.

Similarly, when someone opens the bidding at the one level, he probably has a hand of 12 or more points. If he subsequently makes a minimum raise of his partner’s response or rebids his suit at the lowest available level, he probably has a hand of about 12–15 points. If he makes a jump raise of the responder’s suit or jumps to the three level in his own suit, he probably has a medium-strength hand of about 16–18 points. If the opener jumps in a new suit or takes the responder right to game after a one-level response, he probably has a maximum hand of about 19–21 points.

You can also draw information from what the opponents do not do during the auction. If they stop in a partscore contract, they likely have fewer than 26 combined points. If they stop in a game contract, they probably have fewer than the combined 33 points required for a small slam. If an opponent passes originally and then bids strongly thereafter, he probably has 10–11 points, not quite enough to open the bidding.

Let’s look at some examples of the type of picture you can draw. Suppose you are West and the auction proceeds as follows:

|

North |

East |

South |

West |

|

1 |

Pass |

1 |

Pass |

|

2 |

Pass |

2NT |

Pass |

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

What do we know about North’s hand? He must have four diamonds and 12 or more points to open the bidding 10 and, since he bid them again without support, he must have at least five of them. He did not support his partner’s heart suit at any point in the auction so he must have three or fewer hearts. He did not bid 1 or 2

or 2 at his second opportunity, so he is unlikely to have four cards in either of these suits. He also did not open 1NT or rebid 1NT, so he does not have a balanced hand. What about his strength? He made a minimum rebid at his first opportunity, so we can expect about 12–15 points. He did, however, accept his partner’s invitational bid of 2NT by raising to game. So North should be at the top of his range, 14 or 15 points, counting points for his long suit. We might expect the dummy to come down looking something like this:

at his second opportunity, so he is unlikely to have four cards in either of these suits. He also did not open 1NT or rebid 1NT, so he does not have a balanced hand. What about his strength? He made a minimum rebid at his first opportunity, so we can expect about 12–15 points. He did, however, accept his partner’s invitational bid of 2NT by raising to game. So North should be at the top of his range, 14 or 15 points, counting points for his long suit. We might expect the dummy to come down looking something like this:

What about the declarer’s (South’s) hand? He will have at least four hearts for his 1 response, but is very unlikely to have as many as six of them, since he did not try to suggest that suit as trumps once his partner failed to show support at the first opportunity. His no-trump rebid suggests a balanced hand. With an unbalanced hand, he might have bid another suit or supported the opener’s diamond suit. As far as his strength is concerned, he did not pass the opener’s minimum rebid but also did not go all the way to game, choosing an invitational rebid of 2NT instead. This implies that he has about 11–12 points, enough to invite the opener to carry on to game. A hand consistent with South’s bidding would be something like this:

response, but is very unlikely to have as many as six of them, since he did not try to suggest that suit as trumps once his partner failed to show support at the first opportunity. His no-trump rebid suggests a balanced hand. With an unbalanced hand, he might have bid another suit or supported the opener’s diamond suit. As far as his strength is concerned, he did not pass the opener’s minimum rebid but also did not go all the way to game, choosing an invitational rebid of 2NT instead. This implies that he has about 11–12 points, enough to invite the opener to carry on to game. A hand consistent with South’s bidding would be something like this:

We even know something about our partner’s hand! He does not have a good enough suit or enough points to enter the auction with an overcall or takeout double after the 1 bid. Negative inferences such as this can sometimes be as important as the positive ones gained from the bids made.

bid. Negative inferences such as this can sometimes be as important as the positive ones gained from the bids made.

Thinking about the best lead

Let’s review the earlier auction when the opponents reached 3NT:

|

North |

East |

South |

West |

|

1 |

Pass |

1 |

Pass |

|

2 |

Pass |

2NT |

Pass |

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

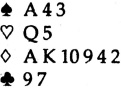

Forming a mental picture of the missing hands helps you decide what to lead when you have a hand such as the following:

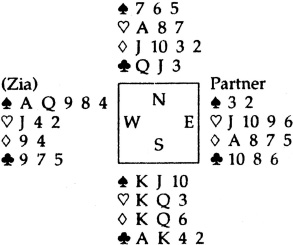

The picture you have constructed from the bidding steers you away from considering a heart or diamond lead, since those are the suits bid by the opponents. It comes down to a choice between the black suits. You need less help from your partner in the club suit than the spade suit, especially since he did not have enough to make an overcall in spades. You reach the conclusion that a club would be the best lead. You are rewarded when the complete hand turns out to be:

Contract: 3NT

On a club lead, the defenders are able to promote three club tricks by driving out the declarer’s  A. The declarer has to give up a diamond trick in order to develop the tricks he needs and the defence ends up with a heart trick, a diamond trick and three club tricks. Did you see through the backs of the cards? Not quite, but you defended as though you had. If you had led any other suit, the declarer would have had no trouble making the contract.

A. The declarer has to give up a diamond trick in order to develop the tricks he needs and the defence ends up with a heart trick, a diamond trick and three club tricks. Did you see through the backs of the cards? Not quite, but you defended as though you had. If you had led any other suit, the declarer would have had no trouble making the contract.

When choosing the suit to lead against a no-trump contract, you usually want to try to find the longest combined suit in the partnership hands. The longer the suit, the more potential for establishing the tricks you need to defeat the contract.

To help find the best suit to lead, consider the following guidelines:

• Lead your partner’s suit – if your partner has opened the bidding or overcalled, unless you clearly have a better alternative. The reason for this is that your partner will have some length in the suit he bid and is likely to have more high cards than you. His high cards will serve as entries to help develop tricks in his long suit.

• Avoid leading a suit bid by the opponents. It is unlikely that you are going to find much help in your partner’s hand if the opponents have bid a suit you are considering leading. Unless you have a very strong sequence to lead from, you are more likely to help the declarer by leading one of his suits. After all, the declarer may also need to get tricks from that suit to make his contract. It cannot be right for both sides to want to attack the same suit.

• Lead your longest suit if there is nothing else to go on. Your longest suit has the best chance of being the longest combined suit in the partnership hands and, therefore, of having the best potential for developing the number of tricks you need.

• Lead the stronger suit if there is a choice of equally long suits – since you will need less help from your partner to develop winners in the suit.

Let’s look at a practical example by considering the following hand from which you have to make a lead against the opponents’ 3NT contract:

If your partner has opened the bidding 1 , or overcalled in spades during the auction, you should lead your spade since you do not have a clearly better alternative. You are hoping to develop tricks in your partner’s suit and that he will have an entry so that he can take them once they are established.

, or overcalled in spades during the auction, you should lead your spade since you do not have a clearly better alternative. You are hoping to develop tricks in your partner’s suit and that he will have an entry so that he can take them once they are established.

If the opponents had bid hearts during the auction, you should avoid leading that suit and, instead, pick the longer of your remaining suits, clubs. If the opponents did not bid anything during the auction, you would choose the stronger of your two five-card suits and lead hearts.

As you can see from this example, you cannot choose the suit to lead until you have first reviewed the auction.

Choosing the card to lead

Once you have selected the suit you are going to lead, you must choose the specific card in the suit that you are going to lead. From the discussions in previous chapters, we can draw up the following guidelines for leading against no-trump contracts:

When leading partner’s suit:

• Lead the top of a doubleton (9 2, Q 3)

• Lead the top of touching high cards (Q J 10, J10 9)

• Otherwise, lead low (Q 7 2, K 8 4 3)

When leading your own suit:

• Lead the top of a three-card or longer sequence (K Q J 7, Q J 10 8 2)

• Lead the top of an interior sequence (K J 10 9, A 10 9 8 5)

• Lead the top of a broken sequence (K Q 10 8, Q J 9 6 2)

• Otherwise, lead low (fourth best) (K J 8 5, A 10 8 4 3)

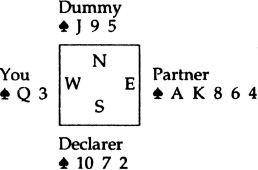

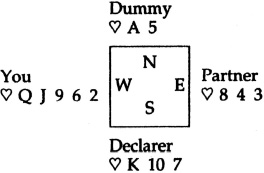

Let’s review the reason for each of these leads in turn. You lead the top of a doubleton in your partner’s suit to avoid blocking the suit. You want to make sure that the high card gets played from the short side first. For example:

By leading the  Q, the defence can take the first five tricks. The situation would be similar if you were promoting tricks, rather than taking sure tricks:

Q, the defence can take the first five tricks. The situation would be similar if you were promoting tricks, rather than taking sure tricks:

If you were to lead a low spade first and your partner’s  K drove out the declarer’s

K drove out the declarer’s  A, your partner could lead a small spade back to your

A, your partner could lead a small spade back to your  Q when he regained the lead. But your partner’s remaining winners would be stranded unless he has an entry in another suit.

Q when he regained the lead. But your partner’s remaining winners would be stranded unless he has an entry in another suit.

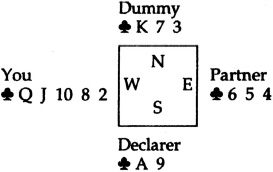

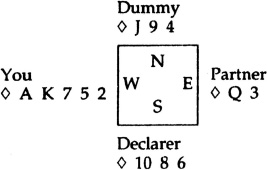

You lead low from three or more cards for two reasons. It helps your partner distinguish between the case where you hold a doubleton and where you hold three or more cards, since you would lead the top card from a doubleton, rather than a low card. It may also help the defenders trap cards in the declarer’s hand. For example:

When you lead the  2, your partner can win the first trick with the

2, your partner can win the first trick with the  A and lead a diamond back, trapping the declarer’s

A and lead a diamond back, trapping the declarer’s  J. On the other hand, if you had led the

J. On the other hand, if you had led the  Q, the declarer would end up with two tricks in the suit.

Q, the declarer would end up with two tricks in the suit.

When leading your own suit, you lead the top of a three-card or longer sequence to prevent the declarer from winning a cheap trick in the suit. For example:

If you were to lead a low club, the  2 or

2 or  8, the declarer would win the first trick with the

8, the declarer would win the first trick with the  9 and still have the

9 and still have the  A and

A and  K left for two more tricks. By leading the

K left for two more tricks. By leading the  Q, you force the declarer to win the trick with one of his high cards. You can subsequently lead the

Q, you force the declarer to win the trick with one of his high cards. You can subsequently lead the  J or

J or  10 to drive out the declarer’s other high card and establish the remainder of your clubs as winners.

10 to drive out the declarer’s other high card and establish the remainder of your clubs as winners.

Another reason for leading the top of your touching cards is to give your partner information. He knows you have the next lower card but not the next higher card. You tell him about the location of three cards all at the same time.

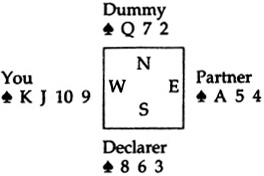

An interior sequence is one in which you have two or more touching cards and you also have a higher card in the suit. Leading the top of your touching cards helps trap cards in either the declarer or the dummy’s hand. For example:

When you lead the  J, the dummy’s

J, the dummy’s  Q is trapped. If the declarer plays the

Q is trapped. If the declarer plays the  Q, your partner wins the

Q, your partner wins the  A and you get four tricks in the suit. If the declarer plays a small spade from the dummy, your partner can let your

A and you get four tricks in the suit. If the declarer plays a small spade from the dummy, your partner can let your  J win the trick and you still end up taking the first four tricks. We can now complete the rule regarding the lead of an honour card thus:

J win the trick and you still end up taking the first four tricks. We can now complete the rule regarding the lead of an honour card thus:

When we lead an honour card, we promise the honour immediately below it and deny the honour immediately above it. For example, the lead of the  Q promises the

Q promises the  J but denies the

J but denies the  K. If the honour led is the queen, jack or ten, then we may or may not have a higher card in the suit. For example, we would lead the

K. If the honour led is the queen, jack or ten, then we may or may not have a higher card in the suit. For example, we would lead the  Q from both

Q from both  Q J 10 and

Q J 10 and  A Q J. We would lead the

A Q J. We would lead the  J from both

J from both  J 10 9 and

J 10 9 and  K J 10. We would lead the

K J 10. We would lead the  10 from both

10 from both  10 9 8 and

10 9 8 and  Q 10 9 or

Q 10 9 or  K 10 9.

K 10 9.

Leading the top of an interior sequence also works well in this type of layout:

You lead the  J and the declarer wins the first trick with the

J and the declarer wins the first trick with the  Q. If your partner gets the lead, he can lead back a spade trapping the declarer’s remaining

Q. If your partner gets the lead, he can lead back a spade trapping the declarer’s remaining  K. The defence ends up with four spade tricks.

K. The defence ends up with four spade tricks.

A broken sequence is one in which you are missing the second or third card in what would otherwise be a four-card or longer sequence. You lead the top of the touching cards to prevent the declarer from getting a cheap trick. You hope that if the declarer has the missing card in the sequence, you will be able to trap it. For example:

If you were to lead a small heart, the declarer would win the first trick with the  10 and end up with three tricks in the suit. By leading the

10 and end up with three tricks in the suit. By leading the  Q, you retain the option to trap the declarer’s

Q, you retain the option to trap the declarer’s  10 in the above situation. The declarer can win the first trick with the dummy’s

10 in the above situation. The declarer can win the first trick with the dummy’s  A, keeping the

A, keeping the  K and

K and  10 in his hand but if your partner gets the lead for the defence, he can lead a heart through the declarer’s strength, trapping the

10 in his hand but if your partner gets the lead for the defence, he can lead a heart through the declarer’s strength, trapping the  10.

10.

Finally, let’s review why you lead a low card when you do not have a strong sequence. One reason is to ensure that, if your partner has a high card, you start by playing the high card from the short side first:

Leading a low diamond lets the defenders take the first four tricks. If you start with a high diamond, the suit becomes blocked. Worse, if you play both the  A and

A and  K, your partner’s

K, your partner’s  Q never takes a trick and the declarer gets an undeserved trick with the

Q never takes a trick and the declarer gets an undeserved trick with the  J.

J.

Leading low also helps to preserve communications between the defenders’ hands in this type of layout:

By leading a low diamond, you ensure that you have an entry back to your winners if your partner subsequently wins a trick. If you started with your high diamonds and then another diamond to establish your small cards, your remaining winners would be stranded since your partner has no diamonds left.

You might hear bridge players giving the advice: “Lead the fourth highest of your longest and strongest suit against a no-trump contract.”

For example, from a suit such as  A Q 8 6 2, you would lead the

A Q 8 6 2, you would lead the  6, fourth down from the top, rather than the

6, fourth down from the top, rather than the  2. This is a conventional way to convey some information to your partner about your length in the suit. It is more important, however, that you understand why you lead a low card, rather than a high card, from such suits.

2. This is a conventional way to convey some information to your partner about your length in the suit. It is more important, however, that you understand why you lead a low card, rather than a high card, from such suits.

Putting it into practice

Let’s put everything together and see what you would lead from the following hands after the auction has gone:

|

North |

East |

South |

West |

|

1 |

1NT |

Pass |

|

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

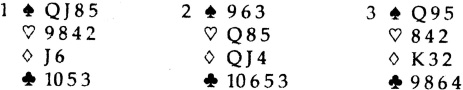

Your partner has bid diamonds so, with nothing better to do, you should lead his suit on each of the hands. On the first hand, you lead the  J, top of your doubleton. On the second hand, lead the

J, top of your doubleton. On the second hand, lead the  Q, top of your touching high cards. On the last hand, lead the

Q, top of your touching high cards. On the last hand, lead the  2, low from three or more cards with no touching high cards.

2, low from three or more cards with no touching high cards.

Now, let’s see what you would lead in each of the following hands after the auction has gone:

|

North |

East |

South |

West |

|

Pass |

1NT |

Pass |

|

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

This time, you have nothing much to go on from the auction, so you will have to look toward your own long suits. On the first hand, you have four cards in both spades and hearts. With a choice, pick the stronger suit. Since you have a sequence, lead the top card, the  Q. With the second hand, the diamond suit clearly represents your best chance to develop tricks. Start with the

Q. With the second hand, the diamond suit clearly represents your best chance to develop tricks. Start with the  10, top of your interior sequence. On the last hand, you are going to try to develop tricks from your long heart suit. With no sequence to lead from, start with a low heart. Traditionally, you would lead the

10, top of your interior sequence. On the last hand, you are going to try to develop tricks from your long heart suit. With no sequence to lead from, start with a low heart. Traditionally, you would lead the  5, fourth highest.

5, fourth highest.

Summary

When leading against a no-trump contract, always stop to review the bidding before choosing the suit to lead. Use the following guidelines:

• Lead your partner’s suit

• Avoid leading a suit bid by the opponents

• Lead your longest suit. With a choice of suits, lead the stronger suit

Having chosen the suit, you must think about the best card to lead. Use the following guidelines:

When leading your partner’s suit:

• Lead the top of a doubleton (9 2, Q 3)

• Lead the top of touching high cards (Q J 8, J 10 9)

• Otherwise, lead low (Q 7 2, K 8 4 3)

When leading your own suit:

• Lead the top of a three-card or longer sequence (K Q J 7, Q J 10 8 2)

• Lead the top of an interior sequence (K J 10 9, A 10 9 8 5)

• Lead the top of a broken sequence (K Q 10 8, Q J 9 6 2)

• Otherwise, lead low (fourth best) (K J 8 5, A 10 8 4 3)

Over Zia’s shoulder

Hand 1 Dealer: West

|

North |

East |

South |

West |

|

Pass |

|||

|

Pass |

1 |

1NT |

Pass |

|

2NT |

Pass |

3NT |

Pass |

|

Pass |

Pass |

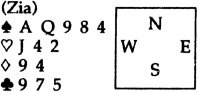

Luckily, my partner had enough strength to open the bidding. With this motley collection of cards, I was expecting the opponents to reach slam. Looking at the nice interior sequence in hearts, what am I going to lead?

Solution to Hand 1:

Contract: 3NT

|

S |

It’s time to stop and review the bidding. My partner has given us a clue what to do by opening the bidding 1 |

|

T |

In thinking about the best card to lead, I am tempted to start with my long heart suit. My partner’s suit takes preference, however. I have no reason to believe that my suit is any better than my partner’s and, even if I can promote some winners, I have no entry back to my hand to help me take them. |

|

O |

There’s no time to waste. I have to lead my partner’s suit right away to avoid giving the declarer the opportunity to establish his suits. Since I am leading my partner’s suit, I start with the |

|

P |

The defenders’ plan springs into action. Leading a spade helps my partner drive out one of the declarer’s high spades. When the declarer leads a diamond to try to establish the tricks he needs, my partner wins and leads another spade to drive out the declarer’s remaining high card in the suit. The declarer leads another diamond to establish his suit, but he loses the race. My partner wins and takes his three established spade winners to defeat the contract. |

If we had led our own suit, we would not have defeated the contract. Apart from being successful, leading my partner’s suit had other advantages. If it worked out badly, at least we have a reasonable excuse. If I had led my own suit and it worked out badly, my partner would have been likely to lose a little of his love for me.

Hand 2 Dealer: North

|

North |

East |

South |

West |

|

Pass |

Pass |

2NT |

Pass |

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

At least I know which suit I’m going to lead against this contract, but which card should I lead? A high spade or a small one?

Solution to Hand 2:

Contract: 3NT

|

S |

The auction has not given us much to go on, but we are going to have to find five tricks to defeat it. |

|

T |

With only one sure trick in spades, we’ll have to try to establish some tricks through length. |

|

O |

We may have to give up a spade trick or two to the declarer in order to establish the suit. Is it better to take the |

|

P |

We lead the |

Leading a small spade is the only thing that works on this hand. If we lead another suit, or start with the  A, the declarer has an easy time making the contract.

A, the declarer has an easy time making the contract.