2 against a no trumps contract:

2 against a no trumps contract:CHAPTER 34

After Partner Leads

Bridge is the only sport where the participants pay at a tournament and the spectators get in free.

When it is your partner who has made the opening lead, you are able to see his first card and the dummy before you have to STOP and make your plan. You have additional information. You should review the bidding to see what clues you have about the cards in the declarer’s hand. Your partner’s lead has also told you more about his hand than just the card he chose to lead. For example, if he has led the top of a sequence, you can expect him to have the next lower card but not the next higher card, and so on. Even the first card the declarer plays from the dummy will provide you with a further clue as to your best plan.

Since you will be the third person to play to the first trick, your position is sometimes referred to as third hand and this chapter looks at some guidelines for third-hand play. Of course, any time your partner leads to a trick throughout the hand, you will be in the position of third hand and can use the same principles discussed here.

Playing third hand high

As third hand, you are the last player to contribute a card to the trick for your side. Unless your partner’s card is clearly going to win the trick, the card you choose to play will be vital in determining which side wins the trick. In general, you want to make your best effort to win the trick for your side, although, as we shall see, sometimes there is more to gain by letting the declarer win the first trick.

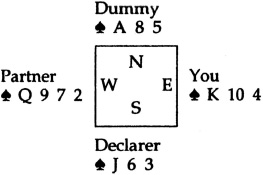

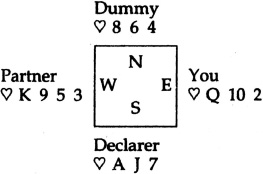

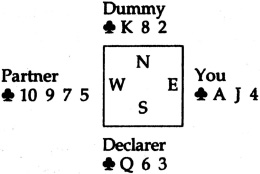

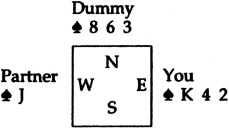

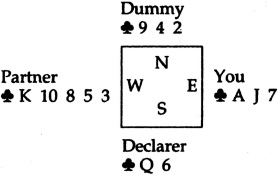

When your partner leads a low card that is obviously not going to win the trick, the general principle you follow is third hand high. That is, you tend to play as high a card as necessary to try to win the trick. Let’s look at an example where your partner has led the  2 against a no trumps contract:

2 against a no trumps contract:

If the declarer plays the dummy’s  A on this trick, then there is nothing you can play to win the trick. That does not mean that the card you play is unimportant. As you will see in Chapter 11, the card you choose can convey important information to your partner. For now, let’s suppose that the declarer plays the dummy’s

A on this trick, then there is nothing you can play to win the trick. That does not mean that the card you play is unimportant. As you will see in Chapter 11, the card you choose can convey important information to your partner. For now, let’s suppose that the declarer plays the dummy’s  5. Which card do you play? Being in third hand, you want to try to win the trick for your side and you can do this by playing the

5. Which card do you play? Being in third hand, you want to try to win the trick for your side and you can do this by playing the  K, third hand high. What about playing the

K, third hand high. What about playing the  10 instead of the

10 instead of the  K, saving the

K, saving the  K for later? The problem with making such a halfhearted effort is that it may cost your side a trick. For example, here is the complete layout of the suit:

K for later? The problem with making such a halfhearted effort is that it may cost your side a trick. For example, here is the complete layout of the suit:

If you play the  10, the declarer will win with the

10, the declarer will win with the  J and still have the

J and still have the  A left as a second trick in the suit. If you play the

A left as a second trick in the suit. If you play the  K, the declarer only gets one trick. His

K, the declarer only gets one trick. His  J is trapped when you return the suit.

J is trapped when you return the suit.

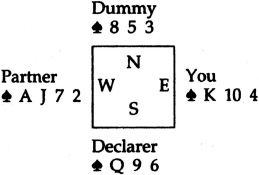

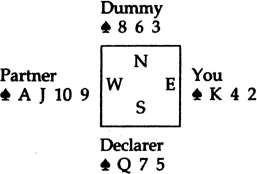

Let’s change the layout slightly:

Now it is not so clear that playing the  K will win the trick. What if the declarer has the

K will win the trick. What if the declarer has the  A? Nonetheless, you should put the guideline to work and play the

A? Nonetheless, you should put the guideline to work and play the  K, third hand high, making your best effort to win the trick. There are a number of possible ways in which the missing high cards might be distributed. Let’s start with an example where your partner holds the

K, third hand high, making your best effort to win the trick. There are a number of possible ways in which the missing high cards might be distributed. Let’s start with an example where your partner holds the  A:

A:

If you feebly play the  10, the declarer will win a trick with the

10, the declarer will win a trick with the  Q. Whereas, if you play the

Q. Whereas, if you play the  K, you will win the trick and can lead back a spade to trap the declarer’s

K, you will win the trick and can lead back a spade to trap the declarer’s  Q. The declarer ends up with no tricks in the suit. Now let’s give the declarer the

Q. The declarer ends up with no tricks in the suit. Now let’s give the declarer the  A:

A:

If you play the  10, the declarer wins the

10, the declarer wins the  J and ends up with two tricks in the suit. Playing the

J and ends up with two tricks in the suit. Playing the  K does not actually win the trick, but it drives out the declarer’s

K does not actually win the trick, but it drives out the declarer’s  A, promoting your partner’s

A, promoting your partner’s  Q into a winner. Better still, if you regain the lead, you can lead another spade, trapping the declarer’s

Q into a winner. Better still, if you regain the lead, you can lead another spade, trapping the declarer’s  J and giving your side three tricks in the suit.

J and giving your side three tricks in the suit.

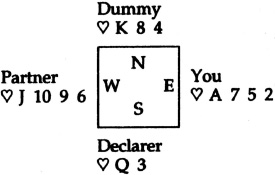

Playing only as high as necessary

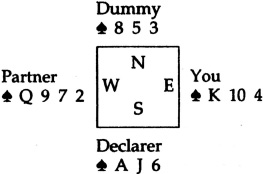

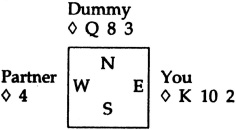

You do not have to play your highest card in third hand, only as high as necessary to make your best effort to win the trick. Look at this layout where your partner has led the  3:

3:

When the declarer plays a small heart from the dummy, your  Q and

Q and  J have equal value. Either one of them could be used to drive out any high card the declarer might hold. In such situations, you should play the lower card, the

J have equal value. Either one of them could be used to drive out any high card the declarer might hold. In such situations, you should play the lower card, the  J. What difference does it make? Let’s look at the complete layout from your partner’s perspective:

J. What difference does it make? Let’s look at the complete layout from your partner’s perspective:

When your  J drives out the declarer’s

J drives out the declarer’s  A, your partner is able to work out that you must hold the

A, your partner is able to work out that you must hold the  Q as well. If the declarer held the

Q as well. If the declarer held the  Q, he would have won the first trick with it, keeping his

Q, he would have won the first trick with it, keeping his  A as a second trick in the suit. If your partner regains the lead, he can confidently lead another small heart to your

A as a second trick in the suit. If your partner regains the lead, he can confidently lead another small heart to your  Q and you could lead your last heart back to his remaining winners.

Q and you could lead your last heart back to his remaining winners.

If you were to play the  Q, your partner will assume that the complete layout is something like this:

Q, your partner will assume that the complete layout is something like this:

If he regains the lead, he will not want to lead another small heart since he would expect that the declarer would be able to win it with the  J.

J.

Playing the lower of touching cards when playing third hand high has a similar effect to leading the top of touching cards. It can help your partner to visualize the location of cards he cannot actually see.

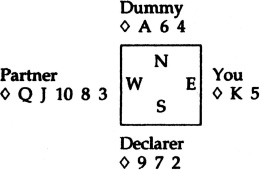

Finessing against the dummy

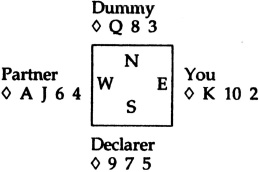

Suppose your partner leads the  4 in this layout:

4 in this layout:

When the declarer plays a small diamond from the dummy, you would play the  J, not the

J, not the  K, since the

K, since the  J is as high as necessary to try to win the trick. The complete layout might be:

J is as high as necessary to try to win the trick. The complete layout might be:

Playing the  J allows the defenders to take the first four tricks in the suit. If you were to play the

J allows the defenders to take the first four tricks in the suit. If you were to play the  K on the first trick, the declarer would eventually get a trick with the dummy’s

K on the first trick, the declarer would eventually get a trick with the dummy’s  Q. Playing only as high a card as necessary in third hand is not always straightforward. Let’s change the situation slightly:

Q. Playing only as high a card as necessary in third hand is not always straightforward. Let’s change the situation slightly:

When your partner leads the  4 and the declarer plays the

4 and the declarer plays the  3 from the dummy, should you play the

3 from the dummy, should you play the  K or the

K or the  10? How high is it necessary to play? The situation is essentially equivalent to the previous layout but it is much more difficult to visualize when you do not have the

10? How high is it necessary to play? The situation is essentially equivalent to the previous layout but it is much more difficult to visualize when you do not have the  J. Let’s look at the complete layout:

J. Let’s look at the complete layout:

If you play the  10, it will win the trick and the defenders can take the rest of the tricks in the suit. On the other hand, if you were to play the

10, it will win the trick and the defenders can take the rest of the tricks in the suit. On the other hand, if you were to play the  K, the declarer would end up taking a trick with the dummy’s

K, the declarer would end up taking a trick with the dummy’s  Q.

Q.

Playing the  10 in the above example is referred to as taking a finesse against the dummy since you are essentially doing exactly that – taking a finesse.

10 in the above example is referred to as taking a finesse against the dummy since you are essentially doing exactly that – taking a finesse.

Many similar situations arise in third hand play and you will have to try to visualize the layout of the missing cards to decide exactly what to do. As a general principle, however, you want to keep the dummy’s high card trapped whenever possible. By playing the  10 in the above layout, you are keeping your

10 in the above layout, you are keeping your  K to trap the dummy’s

K to trap the dummy’s  Q. Here is a similar situation:

Q. Here is a similar situation:

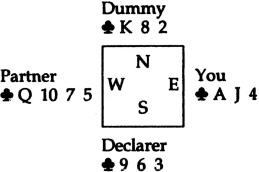

If the declarer plays a low club from the dummy on your partner’s lead of the  5, you should finesse the

5, you should finesse the  J, keeping your

J, keeping your  A to trap the dummy’s

A to trap the dummy’s  K. The layout you are visualizing is something like this:

K. The layout you are visualizing is something like this:

Playing the  A would give the declarer an unnecessary trick with the

A would give the declarer an unnecessary trick with the  K. What if the declarer rather than your partner held the

K. What if the declarer rather than your partner held the  Q? For example:

Q? For example:

The declarer would win your  J with his

J with his  Q, but that is the only trick he gets since the dummy’s

Q, but that is the only trick he gets since the dummy’s  K remains trapped. If you were to play the

K remains trapped. If you were to play the  A on the first trick, the declarer would get tricks with both the

A on the first trick, the declarer would get tricks with both the  K and

K and  Q. This type of situation is similar to that on the following hand. The auction proceeds:

Q. This type of situation is similar to that on the following hand. The auction proceeds:

|

North |

East |

South |

West |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

Pass |

|

3 |

Pass |

4 |

Pass |

|

Pass |

Pass |

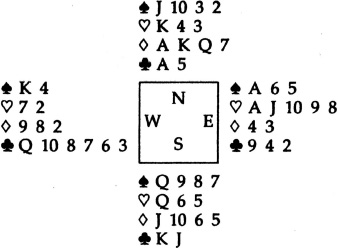

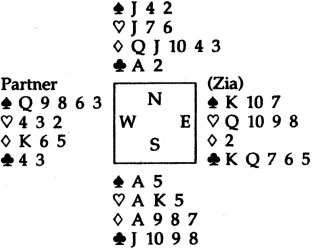

Your partner leads the  7, top of a doubleton in your suit and this is the complete hand:

7, top of a doubleton in your suit and this is the complete hand:

Contract: 4

When the declarer plays a low heart from the dummy, your play as third hand becomes critical to the success or failure of the defence. If you win the trick with the  A, the declarer loses only one heart trick and two trump tricks and makes the contract. Instead, you must visualize the situation and insert the

A, the declarer loses only one heart trick and two trump tricks and makes the contract. Instead, you must visualize the situation and insert the  8, taking a finesse against the dummy and forcing the declarer to win the first trick with the

8, taking a finesse against the dummy and forcing the declarer to win the first trick with the  Q. When your partner regains the lead with the

Q. When your partner regains the lead with the  K, he can lead his remaining heart and the dummy’s

K, he can lead his remaining heart and the dummy’s  K is trapped. Whatever the declarer plays, you win two heart tricks and end up defeating the contract.

K is trapped. Whatever the declarer plays, you win two heart tricks and end up defeating the contract.

Playing after your partner leads a high card

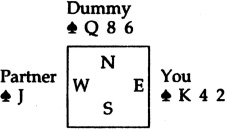

The same principles are used when your partner leads a high card, rather than a low card, and you have to decide what to do in third hand. The difference here is that your partner’s high card may be high enough to win the trick. For example, your partner leads the  J against a no trumps contract and this is the layout you see:

J against a no trumps contract and this is the layout you see:

If the declarer plays a small spade from the dummy, there is no need to play the  K. Your partner’s

K. Your partner’s  J will be high enough to force out the

J will be high enough to force out the  A if the declarer holds it, and will win the trick if he is leading the top of an interior sequence. For example, the complete layout might be:

A if the declarer holds it, and will win the trick if he is leading the top of an interior sequence. For example, the complete layout might be:

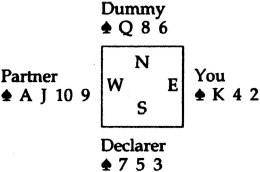

On the other hand, you will have to defend differently if your partner leads the  J and this is what you see:

J and this is what you see:

Your partner’s lead of the  J tells you that he does not hold the

J tells you that he does not hold the  Q and, since it is not in the dummy, the declarer must have it. If you play a low spade, the declarer will be able to win the trick. Instead, you must play the

Q and, since it is not in the dummy, the declarer must have it. If you play a low spade, the declarer will be able to win the trick. Instead, you must play the  K on top of your partner’s

K on top of your partner’s  J, visualizing the layout as something like this:

J, visualizing the layout as something like this:

You can lead back another spade, trapping the declarer’s  Q and taking all four tricks in the suit. What if the declarer, rather than your partner, holds the

Q and taking all four tricks in the suit. What if the declarer, rather than your partner, holds the  A? After all, the complete layout might be something like this:

A? After all, the complete layout might be something like this:

Playing the  K does no harm. The declarer was entitled to two tricks in the suit anyway.

K does no harm. The declarer was entitled to two tricks in the suit anyway.

You still follow the principle of keeping the dummy’s high cards trapped whenever possible. For example:

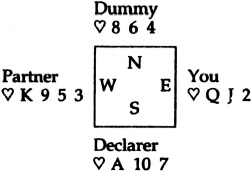

Although your partner’s lead of the  J tells you that the declarer has the

J tells you that the declarer has the  Q, you should not play your

Q, you should not play your  A when a small heart is played from the dummy. You want to keep the dummy’s

A when a small heart is played from the dummy. You want to keep the dummy’s  K trapped if the layout is something like this:

K trapped if the layout is something like this:

Playing the  A would give the declarer two tricks in the suit.

A would give the declarer two tricks in the suit.

Unblocking

We have looked earlier at the importance of playing the high card from the short side when the defenders are taking sure tricks or trying to promote high cards. Here is a situation in which you must be careful to do the right thing in third hand. Suppose your partner leads the  Q against a no trumps contract and the declarer plays the

Q against a no trumps contract and the declarer plays the  A from the dummy in this situation:

A from the dummy in this situation:

You should unblock the suit by playing the  K on the dummy’s

K on the dummy’s  A! The situation you visualize is something like this:

A! The situation you visualize is something like this:

If you hold on to the  K, you have no small card left to lead back to your partner’s winners. You should play the

K, you have no small card left to lead back to your partner’s winners. You should play the  K even if the declarer plays a small diamond from the dummy on the first trick. That way, you can lead your

K even if the declarer plays a small diamond from the dummy on the first trick. That way, you can lead your  5 back to your partner’s hand to help him promote the rest of his winners.

5 back to your partner’s hand to help him promote the rest of his winners.

Returning your partner’s suit

If you win the first trick and are planning to return your partner’s suit, which of your remaining cards should you lead when you have a choice? In general, follow the same principle as when leading your partner’s suit originally. That is:

• Lead the top of a doubleton (9 2, Q 3)

• Lead the top of touching high cards (Q J 8, J 10 9)

• Otherwise, lead low (Q 7 2, K 8 4 3)

In this case, we are talking about the lead you make from the remaining cards in your hand after you have played to the first trick. For example, suppose this is the situation:

Your partner leads the  5 and you play third hand high, winning the trick with the

5 and you play third hand high, winning the trick with the  A. Lead back the

A. Lead back the  J, top of your remaining doubleton. The complete layout might be something like this:

J, top of your remaining doubleton. The complete layout might be something like this:

If you lead back the  7, rather than the

7, rather than the  J, your partner will win the declarer’s

J, your partner will win the declarer’s  Q with his

Q with his  K and can lead the suit again back to your

K and can lead the suit again back to your  J, but now his remaining winners are stranded. Returning the

J, but now his remaining winners are stranded. Returning the  J from your doubleton is following the principle of playing the high card from the short side to avoid blocking the suit.

J from your doubleton is following the principle of playing the high card from the short side to avoid blocking the suit.

Summary

When your partner leads to a trick and you are third to play, keep the principle of third hand high in mind. Only play as high a card as necessary to try to win the trick and, whenever possible, try to keep any high cards in the dummy trapped with your higher cards by finessing against the dummy.

When returning your partner’s suit, lead back the same card from your remaining cards that you would if you were originally leading your partner’s suit.

Over Zia’s shoulder

Hand 1 Dealer: South

|

North |

East |

South |

West |

|

2NT |

Pass |

||

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

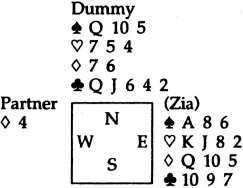

Once again, South seems to hold most of the high cards. I have a few myself, however. How do I plan to put them to use after my partner’s lead of  4?

4?

Solution to Hand 1:

Contract: 3NT

|

S |

We are going to have to come up with five tricks to put this contract down. |

|

T |

The only sure trick we have is the |

|

O |

My partner has chosen the suit in which he wants to develop tricks and, with nothing clearly better in sight, it is up to me to help him out as best I can. It looks as though our plan is to try to establish diamond winners, using our high cards in other suits as entries. |

|

P |

To help put the plan into operation we must start by playing the |

Had we played the  10 or

10 or  5 on the first trick, the declarer would win with the

5 on the first trick, the declarer would win with the  J and have an easy time making the contract after driving out my

J and have an easy time making the contract after driving out my  A. The principle of third hand high made our task easy on this hand.

A. The principle of third hand high made our task easy on this hand.

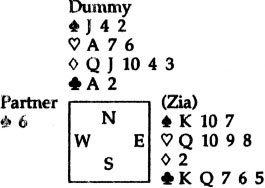

Hand 2 Dealer: East

|

North |

East |

South |

West |

|

Pass |

1 |

Pass |

|

|

1 |

Pass |

1NT |

Pass |

|

3NT |

Pass |

Pass |

Pass |

My partner leads the  6, the declarer plays dummy’s

6, the declarer plays dummy’s  2 and I play... ?

2 and I play... ?

Solution to Hand 2:

Contract: 3NT

|

S |

We need to find five tricks to defeat the contract. |

|

T |

In our hand, there do not appear to be any sure tricks. |

|

O |

We might be able to establish tricks in hearts, if my partner has a high card, or in clubs by driving out the dummy’s |

|

P |

Putting the plan into action, I insert the |

Had we played the  K on the first trick, the defence would have had no chance. The declarer would win with the

K on the first trick, the defence would have had no chance. The declarer would win with the  A and drive out my partner’s

A and drive out my partner’s  K. The dummy’s

K. The dummy’s  J would prevent my partner from taking more than one spade trick and the declarer would make the contract. Thank goodness for those general principles of third hand play!

J would prevent my partner from taking more than one spade trick and the declarer would make the contract. Thank goodness for those general principles of third hand play!