No trumps:

3NT

(9 tricks)

The majors:

4 or 4

or 4

(10 tricks)

The minors:

5 or 5

or 5

(11 tricks)

CHAPTER 4

Developing the Auction

Two bridge writers and players have dominated the game: Ely Culbertson and Charles Goren. In the 1930s, Culbertson went after the popular market. He staged tournaments challenging the best players of the day and this attracted media attention. Ely, however, did more than just this. He looked at his market and decided that his best chance to sell his books was to concentrate on ego, sex and fear.

Through the bidding, a partnership tries to exchange enough information to find the best denomination, either no trumps or a suit if there is a fit of eight or more cards between the two hands. In addition to this, the partnership wants to determine the best zone for the two combined hands in order to get the best possible score.

Introducing the bonus zones

There are three zones: the slam zone, the game zone, and the partscore zone. Since there are bonuses given for bidding and making slams and games, the partnership wants to know if there is enough combined strength to go for one of these bonus zones. This is very important, since the theme of determining the appropriate zone and denomination recurs at every level of the game. Let’s look into this in more detail.

Slams

There are huge bonuses given for bidding and making a grand slam, which is a contract to take all of the tricks (see the appendix for the actual size of the bonuses). To be in a grand slam contract, consider the combined strength you and your partner would need to take all the tricks. If you were in a grand slam, you would want to be reasonably sure that the opponents didn’t have the power to take even one trick. In other words, you want to be sure that the opponents don’t have as much as an ace. Since an ace is worth 4 points, you want the opponents to have no more than 3 points. Since there are 40 high card points in the pack, to have a reasonable chance of making a grand slam the partnership wants to have 37 or more points in the combined hands so that the opponents have, at most, 3 points.

A small slam is a commitment to make all but one trick – in other words, to take twelve tricks. This time you can tolerate the opponents having one ace, but you would not want them to have two aces. The value of two aces is 8 points. To bid a small slam a partnership wants to have about 33–36 points. If a partnership bids a small slam with only 32 points, the opponents could have 8 points, which might be two aces – which would be embarrassing as well as unfortunate!

Although it is a delight to bid and make either a grand slam or a small slam, the experience does not come up that often, so the partnership usually satisfies itself with one of the game bonuses.

Games

There is a game bonus available in each suit. The minimum number of tricks you have to contract for in order to win one of the game bonuses is often within the reach of one of the partnerships on any given hand. There are three different game zones: one for no trumps; one for the major suits; one for the minor suits. The minimum contract on the bidding steps which receives the game bonus in each case is:

Game zones

|

No trumps: |

3NT |

(9 tricks) |

|

The majors: |

4 |

(10 tricks) |

|

The minors: |

5 |

(11 tricks) |

Experience has shown that if your partnership has about 25 combined points, you can usually collect nine tricks in no trumps. When you are playing in a trump suit of eight or more combined cards, you can usually take one more trick than if you were playing in no trumps. So, if you have an eight-card or longer fit in hearts or spades, you also need about 25 points to make 4 or 4

or 4 . If you are going to try to collect eleven tricks for the game bonus in clubs or diamonds, you need a little more, about 28 or 29 points.

. If you are going to try to collect eleven tricks for the game bonus in clubs or diamonds, you need a little more, about 28 or 29 points.

Partscores

The partnership may find out through bidding that there are not enough combined points to consider bidding to one of the game zones. All is not lost, however. The partnership can settle on a partscore and still collect some points. If you discover that your partnership has fewer than 25 combined points, you should stop the auction in a partscore contract, keeping as low as possible on the bidding steps. There is no extra bonus for bidding and making a partscore contract of 2NT rather than a partscore contract of 1NT.

Partscore

No trumps: 1NT or 2NT

The majors: 1 , 1

, 1 , 2

, 2 , 2

, 2 , 3

, 3 or 3

or 3

The minors: 1 , 1

, 1 , 2

, 2 , 2

, 2 , 3

, 3 , 3

, 3 , 4

, 4 or 4

or 4

Since the focus is to aim for a game bonus whenever possible, the partnership’s goal in the bidding can be thought of in this way:

• With 25 or more points, the partnership should reach a game contract.

• With less than 25 points, the partnership should stop in a partscore.

Working as a team

You have to work with your partner so that you can provide each other with enough information to know whether it is reasonable to bid to a game contract or whether to stop in a partscore. In order to be successful in this regard, it helps to have a clear picture of the role of each partner. This is one of the most overlooked strategies of the game and yet it is the most important. Knowing the role expected of each player will make your game much more relaxed.

First of all, let’s suppose that your partner opens the bidding 1NT. Which player knows approximately how many combined points the partnership has? You do. Your partner, the person who opened 1NT, knows nothing about your hand but you know that your partner has specifically 12, 13 or 14 points. Not only that, you know that your partner has a balanced hand. You have a lot of information. As a matter of fact, when you add what you have in your own hand to what your partner has, you usually have enough information to place the contract (decide what the final contract should be). For that reason, your role is that of captain. On the other hand, your partner, the opener, is playing the role of describer, trying to paint an accurate picture of his hand so that you can make the appropriate decisions. It is wonderful when the opener makes a limit bid, such as 1NT, which with only one bid paints such a clear picture for the captain.

Acting the roles

During the bidding, the partnership is exchanging enough information to decide on both the appropriate zone and the appropriate denomination. Since those are two distinct decisions, the captain considers two questions:

• What is the best zone for the partnership?

• What is the best denomination for the partnership?

Deciding on the zone

When the opening bid is very specific, a 1NT opening, for example, the captain often has enough information to decide whether the partnership has the combined strength to go for the game bonus. It is a matter of adding up to 25. The captain adds his points to the point count range promised by his partner, mentally checking the total. For example, let’s suppose your partner opens the bidding 1NT and you have exactly 13 points in your hand:

12 + 13 = 2513 + 13 = 2614 + 13 = 27

Whether your partner has 12, 13 or 14 points, the partnership has a combined total of at least 25 points, which should be sufficient to get to the game zone. So, if your partner opens the bidding 1NT, you, as captain, know that your side belongs in a game-zone contract whenever you hold 13 or more points.

On the other hand, suppose your partner opens the bidding 1NT and you have the following hand:

You have only 10 points. Since your partner’s 1NT opening bid describes a balanced hand with 12–14 points, you know that the most your partner could have is 14 points. The total, 24 combined points, is not enough for the game zone. So you, as captain, want to ensure that the partnership stays in the partscore zone, keeping as low as possible on the bidding steps. Whenever your partner opens the bidding 1NT and you have 10 or fewer points, stop the auction in the partscore zone.

If you know that the partnership belongs in the game zone when you have 13 or more points and belongs in the partscore zone when you have 10 or fewer points, what happens when you hold 11 or 12 points and your partner opens the bidding 1NT? You cannot be certain whether the partnership belongs in a game or a partscore. For example, suppose you have exactly 12 points. Knowing the range of the opening 1NT, you can do the following calculations:

|

Partner’s points: |

12 |

or |

13 |

or |

14 |

|

Your points: |

12 |

12 |

12 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Combined total: |

24 |

or |

25 |

or |

26 |

If your partner has only 12 points, you belong in a partscore. If your partner has 13 or 14, you belong in a game. You, as captain, are in a position where you need more information about the opener’s strength before you can make the final decision. In this situation, rather than decide immediately on the best game or partscore contract, you will have to make a bid that gets you more information about opener’s hand. We will discuss that in more detail in the next chapter. For now, it is sufficient to know that when you have 11 or 12 points and your partner opens the bidding 1NT, the captain cannot make an immediate decision.

Deciding on the denomination

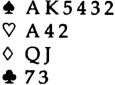

In addition to describing the strength of the hand, a 1NT opening bid tells the captain about the distribution of the hand. The opener is describing a balanced hand with two or more cards in each suit and no more than five in any suit. Again, it is a matter of addition for the captain to determine whether the partnership should be playing in a suit contract or in no trumps. Consider this hand:

With 14 HCPs there are enough points to decide that you want to be in the game zone. As captain, you now have to decide on one of the game zone contracts: 3NT, 4 , 4

, 4 , 5

, 5 or 5

or 5 . Although you might consider 3NT, since it requires only nine tricks, there is a better choice. You know that your partner has at least two spades, giving you a combined total of eight cards in the suit. As we mentioned earlier, when you have an eight-card or longer major suit fit, you want to play there in preference to no trumps. With a trump suit, you will usually lake at least one more trick than in no trumps since you will be able to trump the opponents’ high cards when you have no cards left in a suit. On this hand, then, 4

. Although you might consider 3NT, since it requires only nine tricks, there is a better choice. You know that your partner has at least two spades, giving you a combined total of eight cards in the suit. As we mentioned earlier, when you have an eight-card or longer major suit fit, you want to play there in preference to no trumps. With a trump suit, you will usually lake at least one more trick than in no trumps since you will be able to trump the opponents’ high cards when you have no cards left in a suit. On this hand, then, 4 is likely to be a better game zone contract than 3NT. Since you are the captain, that is the decision you should make. You bid 4

is likely to be a better game zone contract than 3NT. Since you are the captain, that is the decision you should make. You bid 4 . The bidding conversation would sound like this:

. The bidding conversation would sound like this:

|

Partner: |

One no trump. |

(I have a balanced hand with 12–14 points.) |

|

You: |

Four spades. |

(Thank you. That tells me all I need to decide that we belong in the game zone and that spades would be the best trump suit.) |

|

Partner: |

Pass. |

(You’re the captain!) |

If you and your partner are North-South, the complete auction would look like this:

|

North (Partner) |

East |

South (You) |

West |

|

1NT |

Pass |

4 |

Pass |

|

Pass |

Pass |

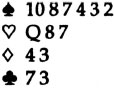

Let’s change your hand by removing some of the high cards:

Now, when your partner opens the bidding 1NT, you can see at a glance that the partnership does not have enough strength for the game zone. You have only 2 HCPs. Even if your partner has a maximum of 14 points, the total is only 16 points. You might think that all you have to do is to say ‘Pass’. After all, you do not have a very good hand and 1NT is one of the partscore contracts. But remember, you are the captain. What do you really think is the best choice for the denomination, no trumps or spades?

Again, apply the principle that an eight-card fit in a major suit is better than playing in no trumps. You are likely to agree that spades is a better place to play. After all, if spades are trumps you can at least stop the opponents from taking too many diamond or club tricks by trumping the third round of either suit. If you are still not convinced, try making up a 1NT opening bid and putting this hand opposite it. Try to play the contract in no trumps and then with spades as trumps. We think you’ll end up convinced that the best denomination is in spades. In order to put your conviction into practice, all you have to do is to bid 2 . The conversation with your partner would go like this:

. The conversation with your partner would go like this:

|

Partner: |

One no trump. |

(I have a balanced hand with 12–14 points.) |

|

You: |

Two spades. |

(Thank you. That tells me all I need to decide that we belong in the partscore zone and that spades would be the best trump suit.) |

|

Partner: |

Pass. |

(You’re the captain!) |

Deciding on the denomination won’t always be this easy. Just as you are not always sure about whether or not you want to play in a game zone or partscore zone, there are times when you may be unsure of the denomination. For example, you might have a hand like this:

With 13 HCPs, you are satisfied that you want to move to the game zone. The best game contract might be 4 , if your partner has three or four cards in spades, giving you the magic eight-card fit. But if your partner has only two spades, the best game contract is almost certainly 3NT. You are the captain, but you need some more information from your partner! To help make your decision, you would like to know how many spades your partner has. If he has three or more, you want to play in your eight-card fit. But, if your partner has only two, then playing in no trumps is likely to be the best decision. This is another case where you have some answers, but not all of them. So you want to suggest playing in spades but keep the option to play in no trumps if your partner has only a doubleton in spades. In the next chapter, we will see exactly how you conduct the bidding conversation to get the answer you require.

, if your partner has three or four cards in spades, giving you the magic eight-card fit. But if your partner has only two spades, the best game contract is almost certainly 3NT. You are the captain, but you need some more information from your partner! To help make your decision, you would like to know how many spades your partner has. If he has three or more, you want to play in your eight-card fit. But, if your partner has only two, then playing in no trumps is likely to be the best decision. This is another case where you have some answers, but not all of them. So you want to suggest playing in spades but keep the option to play in no trumps if your partner has only a doubleton in spades. In the next chapter, we will see exactly how you conduct the bidding conversation to get the answer you require.

The general idea behind the captain’s role is that, after your partner opens the bidding with a very specific bid like 1NT, you are in a position to decide on one of the following courses of action:

• To place the final contract in the game zone, either in a suit or in no trumps

• To place the final contract in the partscore zone, either in a suit or in no trumps

• To get more information about partner’s strength or distribution before making the final decision

Bidding messages

During the auction, it is comforting to know whether your partner expects you to pass or to bid again. From the other side of the table, it is equally comforting to feel confident that your partner will pass or will bid again after you have made a certain bid. In other words, we have expectations of our partners. These expectations, or bidding messages, fall into three categories:

• We expect our partner to pass our last bid

• We don’t mind if our partner passes or bids again

• We would like to insist that our partner bid again

We can’t hide these expectations, nor should we want to. They are a vital part of the game. Partnership misunderstandings can best be solved if you know that each bid carries with it a message. To help you recognise the message, think of a traffic light:

|

|

Sign-off |

Some bids are red. You expect your partner to pass at his next opportunity. These bids are called sign-off bids. |

|

Invitational |

Some bids are amber. You want your partner to proceed with caution, but you do not want specifically to instruct your partner to pass or to bid again. These bids are called invitational bids. |

|

|

Forcing |

Some bids are green. You expect your partner to bid again. These are called forcing bids. |

Over Zia’s shoulder

|

Audrey: |

Zia, you are known as one of the most imaginative players in the world. When your partner opens the bidding – more specifically, Zia, when your partner opens the bidding 1NT – do you go through the addition steps to figure out if there is a game and then do you ask yourself about the denomination? |

|

Zia: |

No matter how imaginative you are, or how much experience you have, you have to go through the process. After a while, it becomes so quick that it may seem as if you are making the decisions without thinking which, of course, is not true. For example, here is a hand I held after my partner opened the bidding 1NT: |

|

|

|

|

I knew I wanted our partnership to be in the game zone. I have 12 HCPs and I take into consideration the length in the diamond suit. Since my partner has at least 12 points, that adds up to a total of at least 24, plus the diamond suit. My next decision is to consider the denomination. Here my decision is based on the fact that I want to move the partnership to a game contract. The choice of contract, then, is between 5 |

|

|

Audrey: |

What did you decide? |

|

Zia: |

Like most people, I like to play the hands and by bidding 5 |

|

Audrey: |

Give us another hand which you held after your partner opened the bidding 1NT. |

|

Zia: |

Here is a hand where I have HCPs and a long heart suit, so I know I am in the game zone. |

|

|

|

|

My next question would be the same as a player who is just learning the game. Since, as captain, I have decided to lead the partnership to game, I ask myself what game? Two choices come to mind, either 4 |

|

|

Audrey: |

And how will you do that? |

|

Zia: |

We will look at the specific bid in the next chapter, but the important thing is that, if I ask myself what zone and what denomination the partnership should be in, I know what message I would like my bid to convey. With this hand, I want my bid to ask my partner for more information about the denomination, not about the zone, since I already have that answer. That is what determines the course I must take. |

|

Audrey: |

Have you ever been tempted to ignore the bidding message that your partner is sending you? |

|

Zia: |

Very rarely. For example, with the following hand I held the other day, I opened 1NT. Nothing too challenging at that point. Then my partner bid 2 |

|

|

|

|

I knew my partner was asking me to pass. Now, I could have looked at my hearts longingly and thought that this was the time to bid again, in spite of my partner’s request. But you have to ask yourself, why has my partner asked me to pass? My partner, the captain, had decided from the very specific picture that I gave by bidding 1NT that the best spot was a partscore in hearts. I had no reason to object. This is what my partner had: |

|

|

|

|

|

You can see that if we went any higher, even though we have a strong trump suit, we would be in trouble. On the actual hand the opponents took three tricks in spades and two club tricks before we had a chance to take the lead. My partner had made a good decision and I was glad that I had respected his message. |

Summary

When your partner opens the bidding, he is playing the role of describer, trying to paint a picture of his hand. If he makes a bid which describes his hand within narrow limits, such as 1NT, that puts you in the role of captain, trying to determine the contract in which the partnership belongs. After your partner’s opening bid, you need to consider two questions:

• What zone would it be best for us to play in?

• What denomination would it be best for us to play in?

Your decision about the zone is answered by adding together the range of strength promised by the opener to the exact strength which you can see in your own hand. Once you come up with the possible combined total, you can set your sights on the appropriate zone using the following guidelines:

|

Zone |

Points required |

|

Grand slam |

37 or more |

|

Small slam |

33 or more |

|

Game |

25 or more |

|

Partscore |

Less than 25 |

The decision about the denomination is guided by the number of cards you have in each suit combined with the number of cards that the opener has promised through his description of the hand. With eight or more combined cards in a major suit, always choose a contract in hearts or spades. With eight or more combined cards in a minor suit, choose a contract in clubs or diamonds unless you think you have a better chance at a game bonus in no trumps; then choose no trumps.

Bidding messages

Each bid carries one of three messages:

|

• Sign-off |

(Red – STOP) |

|

• Invitational |

(Amber – PROCEED WITH CAUTION) |

|

• Forcing |

(Green – GO) |

As we move to the next chapter and look at responses to opening bids of one in a suit, we will consider the message given by each response. It is so much easier to come up with a bid if you understand the message that your partner is sending.

Commonly asked questions

Q When you have eight or more combined cards in a minor suit and enough combined points for the game zone, would you ever take the risk of playing in 3NT when you have a small singleton or doubleton in another suit?

A If you have only 25 or 26 combined points and a fit in a minor suit, you have three choices: you can decide to be conservative and play for a partscore in the minor suit; you can decide to be aggressive and play for a game in the minor suit, even though that normally requires 28 or 29 points; or you can decide to take a chance that your 25 or 26 combined points will be enough to let you take nine tricks in a 3NT contract, despite your shortness in some suits. Each choice has its advantages and disadvantages, but most players prefer to take a chance on 3NT. There is no perfect solution for hands like these. Sometimes, you may have such shortness in one or more suits, or the opponents may have bid a suit for which you have no protection, that you decide to play in a minor suit in either the game or partscore zone. Zia personally uses the maxim: ‘When in doubt bid 3NT.’ At least, he says, he has lots of fun taking the risk and going for the game bonus.

Q Is it always the partner of the opening bidder who is the captain?

A After an opening bid of 1NT, because the opening bidder’s partner knows so much, he is the captain. After an opening bid of one of a suit, there are times, as we shall see, when the opener may become the captain. To keep things simple, however, you should consider that the opener’s partner is always the captain, although he may need to ask the opener’s help when making a decision.