Certain things just can’t be explained in the mass-market press, and the London Whale trade that caused billions of dollars in losses for JP Morgan is one of them. For one thing, JP Morgan refused to offer any details about what its trading desk did—and for another, what its trading desk did was so mind-bendingly complex that few journalists could even understand it, and none could explain it in a way that the average newspaper reader could comprehend. This is where the blogosphere comes in. Matt Levine, an equity-derivatives geek turned blogger, understands complex concepts and can talk about them in a conversational and even funny way. This stuff isn’t easy. But for people who wanted to really get up to speed on a hugely important story, there was only one place to turn.

Hi! Would you like to talk about the London Whale? Sure you would. The amount of misunderstanding of our poor beleaguered beluga is staggering, so I figured we could try to embark on a voyage of discovery together. Maybe we’ll figure it out. Along the way we’ll talk a tiny bit about the Volcker Rule. I am going to try to talk very slowly and simplify things so if you are pretty financially sophisticated you could skip this post (I’ve linked to some better things to read at the end), or just get really angry at me in the comments. Also this post is terrifyingly long, sorry!

So. You are JPMorgan. People come to you and give you money because you are a bank, and they want you to hold on to their money for them. You pay them interest so you need to invest their money to earn interest—ideally you earn more than you pay so you can make money and pay bonuses and stuff. You invest that money, broadly speaking, by lending it to other people who want to do things with it. Some of those people are buying houses; some of them are running businesses. Those are the main ones. (Some are buying cars or educations; others are running countries or municipalities. Ignore that.)

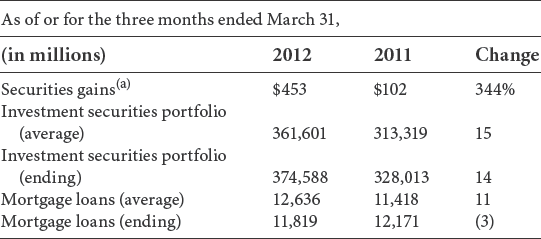

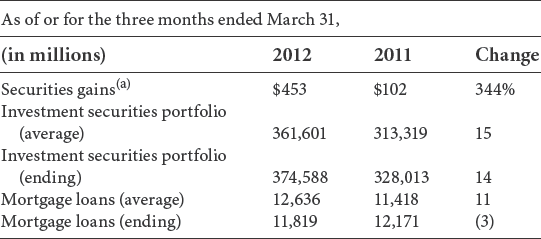

Now a tangent, which is long but important. Some of the money that you lend to people running businesses, you actually lend to people running businesses—like, they come to you and ask you for a loan and you give it to them. Some of it you don’t because you don’t have enough good loans to make—not enough people come to you for loans because they’re not building factories because Obama or whatever, or people do come to you for loans but it’s for terrible things so you say no. So you have “excess deposits,” deposits that you haven’t loaned out, and you invest those. You invest those in securities—that is, loans that someone already made and packaged into bonds to be bought and sold on the market. Since you are by hypothesis JPMorgan, you do this investing of excess deposits through your Chief Investment Office, or CIO, which is staffed by cetaceans. You can tell how much of this investing JPMorgan does because they disclose it on page 33 of their Form 10-Q filed with the SEC yesterday:

Treasury and CIO: Selected Income Statement and Balance Sheet Data

(a) Reflects repositioning of the Corporate investment securities portfolio For further information on the investment securities portfolio, see Note 3 and Note 11 on pages 91–100 and 113–117, respectively, of this Form 10-Q. For further information on CIO VaR and the Firm’s nontrading interest rate-sensitive revenue at risk, see the Market Risk Management section on pages 73–76 of this Form 10-Q.

Now these investments are absolutely 100 percent without any doubt whatsoever “proprietary” in the sense that you have bought them with money and hope for them to pay you back with interest, as opposed to hoping to sell them immediately to a customer. And there is a thing called the Volcker Rule intended to prohibit “proprietary” trading. So this portfolio violates the Volcker Rule, right? No, not at all. The Volcker Rule applies to proprietary positions held in the trading book and intended to be sold within sixty days. As a rough cut, it appears that the CIO positions are mostly longer-term, which is what you’d expect from a bank investing its deposits that would otherwise be put in three-to-seven-year corporate loans or thirty-year mortgages.1

Okay so now you’re JPMorgan and you’ve got about $375 billion worth of securities in the CIO—alongside some $700 billion of loans (page 87 of the 10-Q), of which $115bn are in your commercial bank (lending to businesses—page 28), $70bn are in your investment bank (lending to bigger businesses—page 16), $240bn are in retail (basically mortgages and stuff—page 18), and $187bn are in card services and auto (credit cards, car loans, student loans—page 25). So you have $185bn of corporate loans, plus whatever chunk of that $375bn CIO position is corporate bonds, which seems to be about $60bn (page 92). And you have something called “lending-related commitments,” meaning revolving credit commitments where you have agreed to lend companies money if they ask for it—that number is almost $1 trillion (page 51), presumably almost all corporate. Add to that the fact that your investment bank involves buying and selling lots of corporate bonds as a market-maker, and doing derivatives with corporations where they might owe you money (something like $100bn, page 51 again), and you get the sense that JPMorgan has a lot of exposure to corporate credit. Meaning that if corporations start going bankrupt, JPMorgan will lose a lot of money.

That’s obvious—they’re a bank, that’s what happens to banks, they lend money and if the borrowers don’t pay it back then they are sad. Here if none of their corporate borrowers (leaving aside governments, mortgage borrowers, etc.) pays them back a cent, they lose in round numbers $250 billion on loans, $100 billion on trading receivables, and up to $1 trillion more if those borrowers draw their revolvers before defaulting (as they are wont to do).

THAT WOULD BE TERRIBLE.

But here is another important thing to realize. If instead of defaulting, companies just Became Shakier Credits—that is, if the market decided that all those companies looked less likely to pay their debts—JPMorgan would, to a first approximation, be pretty okay. Because to some rough approximation JPMorgan doesn’t care about the day-to-day swings in creditworthiness of their borrowers; they care about getting paid back at the end. Banks do a thing called “maturity transformation,” meaning that in some loose sense their social function is to lend money to companies and then wait for it to be paid back, instead of just consigning those companies to borrowing afresh every day from fickle liquidity-hungry investors. This is reflected in their accounting: the loans are reflected on an accrual basis; that is, there is some loss reserve against them which can change as they get less likely to be repaid, but JPMorgan doesn’t book a profit or loss every time the market value of those loans goes up or down. Similarly the CIO securities are for the most part “available-for-sale,” meaning again that JPMorgan’s income (for accounting) doesn’t reflect changes in their value, unless and until they’re sold for a profit or loss.

So now we have to get a little bit technical and we can’t avoid it, I am sorry, but here we are, we’ll hold hands and go slow and it will be okay. You want to hedge your risk that things will go horribly pear-shaped and lots of your borrowers don’t pay you back. (You can handle some regular number of them not paying you back—you’re a bank, that’s your job—but if things are worse than expected and a lot of them go belly-up that’s a problem for you.) One thing that you could do is just buy massive quantities of something called CDS, for “credit default swaps,” which function to a first approximation like insurance on corporate debt and pay off if a particular corporation defaults. You could buy CDS on every company you lend to in the amounts that you lend, but (1) this would eat up all your profits and (2) you can’t really, it doesn’t trade for all of them. But you could instead buy CDS on an index—basically a contract that references 125 big companies, and if some of them default it pays off a little and if all of them default it pays off a lot. That won’t exactly match your profile—why would you be lending to those 125 companies and no others?—but the idea here is that if things go horrible, they will go horrible across the board, and your payouts on the index will have some rough match with your losses on your lending. Just a rough match, not perfect.

So you could probably try to buy index CDS—sometimes this is called CDX, after a particular index that is traded a lot, think of it as standing for “Credit Default indeX” because in finance, true story, “index” starts with an “x”—on, what, $1.35 trillion of corporate exposure. But you won’t do that for bunches of reasons. One is that there’s not nearly enough of it—all of the index CDS in the world, combined, including investment-grade and high-yield debt, tranched and untranched, American and European and Australian, everything, adds up to about $11.2 trillion of “notional” (just the amount that is “insured”), and for you to get 12 percent of that seems pretty hard and for you to get the right 12 percent—the stuff that correlates with your risk—seems impossible. Another is that you would basically be spending all your profits from lending2 on the CDS, so you’d have no money left over to do things like buy computers or rent office space or pay bonuses. A third is that, the way CDS works, it is accounted for on a mark-to-market basis, but remember that your loans are not (see two paragraphs ago). So if credit got better, you would have a creepy loss in your income statement because you would “lose money” on your CDS and not “make money” on your loans and securities. If you are a bank, “losing money” for accounting purposes is actually a big deal not only because people get mad at you and stuff but also because it affects how well capitalized you are—lose enough money, on a mark-to-market basis, and you could get shut down. (This, again, is part of why you don’t take mark-to-market gains and losses on your loans.)

That is your problem—you want to hedge against a disaster, but you can’t just buy insurance against anything bad happening. So what you do is you conceive of a trade that:

• pays you plenty of (real) money on a disaster, but

• doesn’t cost you a lot of (real or fake/mark-to-market) money on a nondisaster, like regular market moves

What is that trade?

Well, it starts by buying credit protection on things that make you a lot of money if things go bad. What you’re looking for here is a concept loosely called “leverage,” which means loosely that you don’t pay very much now but get a lot of money if things go bad very quickly. Think of it as: rather than pay for something that moves down a bit when credit improves a bit and up a bit when it worsens a bit, you’re paying for something that moves down a lot when credit improves a bit and down a lot when it worsens a bit. Some types of protection that do that are:

• buying very short-dated credit protection, like a credit index set to expire in December 2012, so that if things get really bad really fast you are ready for it,

• buying protection on something called “tranches,” which pay you relatively more for the next few defaults among the companies in the index, rather than paying you the same amount for all defaults in that index, and/or

• buying protection on high-yield indexes (junk bonds!), which are likely to go bankrupt faster if things get bad

It seems very likely that JPMorgan’s CIO did some or all of the above. It is hard to know! There is a deep mystery—if you like mysteries (and derivatives!) you can read the links above, but the deepest part of the mystery is that when all the hedge funds were complaining to Bloomberg about how JPMorgan was writing lots of protection on CDX.IG.NA.9 (next paragraph), no one was complaining that they were buying the protections mentioned above. I have no solution to the mystery and neither, it appears, does anyone else outside of JPMorgan. [Update: untrue! Meet me in the usual place.3]

Okay anyway though, this hasn’t solved any of your problems except maybe the size one (because you are buying lesser amounts of more intense protection). You are still paying money for protection, and you still lose money if credit improves. So you do the second half of this trade: you “write protection” (sell CDS) on the broad index. This is, again, very approximately like selling an insurance policy: you take in money now, and pay out some money if the companies in that index default. JPMorgan’s CIO very clearly did exactly that, on an index called the CDX.IG.NA.9 10-year, which despite the name matures in 2017. Intuitively—though it doesn’t quite work this way for curve trades so if you know about credit trading you’ll want to skip the rest of this sentence—you need to sell more of this broad protection than you bought in the previous paragraph because what you bought in the previous paragraph was more intense than what you’re selling, so that’s why the whale sold so very much protection on this index.4

So what have you done? Something in outline like the following:

• You are getting money in on one end by selling protection and paying it out on the other by buying protection, so you are not paying out all of your profits.

• You have a position that is relatively neutral to credit market moves: if credit markets move up a bit, your big CDS-writing trade moves up a bit (you make some money), and your smaller but more intense CDS-buying trade moves down a lot (which, multiplied by the smaller size, means you lose some money, and they sort of offset). This is called being “DV01 neutral” but don’t worry about it. The point is that you don’t have huge mark to market losses when markets go up or down regular amounts.

• You have a position that makes a lot of money on bigger moves. So if a bunch of companies go bankrupt your really intense trade pays off a lot, while your less intense trade doesn’t cost that much. So in the really bad state of the world this is a good hedge for you. This is called being “long convexity” or “gap risk” but don’t worry about it.

There is much complexity swept under the rug here but the concept is a bet something like this:

• Take 100 companies

• For each one that goes bankrupt, you pay me $2

• For the first five that go bankrupt, I’ll pay you $1 each

• For the next five that go bankrupt, I’ll pay you $3

• For the next ten that go bankrupt, I’ll pay you $5

• If more than 20 go bankrupt, you don’t get any more—I’ve paid you the max of $70.

You lose a bit but not a lot if things stay good, you break even if things go mediocre, and you do great if things are really bad. (But there’s some horizon where if things are really really bad, more than thirty-five defaults, you start to lose again. This may or may not be a feature of JPMorgan’s bets.)

It seems fairly certain that in broad concept this is what JPMorgan’s Chief Investment Office was doing. But the above allows for lots of nuance. You want a hedge that is basically flat when things are basically okay, and pays out a lot when things are terrible. But define “flat,” and “okay,” and “a lot,” and “terrible.” These are hard judgments and are influenced by your expectations about the world. If you think that there are likely to be only two to three defaults, then the bet above looks like a real disaster hedge: it loses money in the expected case but pays off a lot if there are a staggering, unlikely twenty defaults. But if you think that there are likely to be thirty to forty defaults, then the bet above looks ridiculously optimistic—not a hedge at all, but rather something that loses money if things are at the bad end of expectations.

What seems, loosely, to have happened to the Whale is a combination of things. One is, he got more optimistic and so sold more protection—making the bet relatively more bullish, though not absolutely bullish. It is almost certainly—though who knows?—not correct to say, as everyone does, that Iksil was long $100 billion of corporate credit in his CDX book. It is certainly correct to say that the CIO was overall long credit—that’s what it does! invest JPMorgan’s money in credit instruments!—or that JPMorgan as a whole was long credit—it’s a bank!—but the credit derivatives book probably was a hedge designed to hedge tail risk.

The second is, his model was wrong. At a bank, that little flow chart of the bet that I set out above gets programmed into a computer, and the computer knows your cash flows and what the expected value of them is based on market conditions. If the market is predicting seven defaults, the computer knows that, and knows that I will pay you $14 and you will pay me $11, and it will discount those cash flows and spit out a present value of the bet based on current market conditions. But it’s hard to know what the market is predicting, and the actual bets were vastly more complicated than this, and so it turns out that the computer just got it wrong. Bad computer! Bad people who programmed it! Bad people who relied on it without checking! But these things happen; the surprise is that they happened at JPMorgan, which usually avoids them.

The third is, people figured out it was him, talked to Bloomberg, and started picking him off—making it more expensive for him to do his trades (in the sense that he showed mark-to-market losses). They did this on a bet that eventually he would have to unwind his position and they would make money. They did.

You can draw various lessons from this and I guess you have. There’s the Volcker Rule, of course, and it’s safe to say that everyone’s suspicious about whether this is, or would be, or should be, allowed by the Volcker Rule as a “hedge.” What does it hedge you ask? Well, the thing I described above in excruciating detail hedges JPMorgan’s risk of a lot of corporate bankruptcies. Yes, you say, but what does Bruno Iksil’s $100bn CDX long credit position hedge? Well, it hedges his short credit position. Which hedges JPMorgan’s overall long credit position. OKAY, you say, and walk away in disgust to write a bigger Volcker Rule.

Hedging is hard because you can only try to hedge with things that you expect to be correlated in the world that might come about, and you don’t really know what state of the world will actually occur or what will be correlated with what in that world. You win some you lose some, out of failure in foresight or model error or the other side of the trade trading against you.

What does that argue for? I don’t think it argues anything at all about the Volcker Rule: banning hedging can’t be a solution, and banning something that you call “portfolio hedging” doesn’t fix bad models (or tell you what a “portfolio” is). Obviously this looks “prop” if you focus on one part of the trade, but that is as always in the eye of the beholder. Iksil didn’t think he was betting on corporate credit improving; he thought he was adjusting his hedge to address current market conditions.

The more sensible response, if you want to prevent this sort of thing from blowing up the universe, is something like “stop doing sophisticated things” or at least “raise unsophisticated but large amounts of capital against your sophisticated things.” Because obviously forcing JPMorgan to have capital equal to 20 percent of its non-risk-weighted assets would make it less likely that this would bring down JPMorgan. So, fine, that’s probably right. But JPMorgan’s Basel III capital (for what it’s worth!) is down like twenty basis points on the loss, and there’s no evidence at all that this brought down JPMorgan or did anything close to it. That’s not much of an argument—many other banks are less well capitalized, and less well endowed with modeling skills, than JPMorgan, so if this did some small damage there it could do much larger damage elsewhere. On the other hand, there’s at least a chance that JPMorgan is doing more sophisticated-cum-dangerous trades than other, less sophisticated banks because it is more sophisticated, and the reason that this screw-up happened at JPMorgan is that only JPMorgan dared to dream big enough to screw up this big.

Anyway. Here are some great things to read on Whaledemort if you are too smart to profit from the above:

• You have presumably already read Lisa Pollack, but if not what are you doing here?

• I don’t really know what Felix Salmon is talking about here, but this is good, not only because he’s nice to me

• Kid Dynamite will tell you a relevant story

• Peter Tchir does some relevant digging

• Sonic Charmer has some relevant things to say about the Volcker Rule

• Deus ex Macchiato is brief and sensible5

Notes

1. Without getting into it too much, it seems that the CIO portfolio and JPMorgan’s available-for-sale securities match up in size and stated intent; see, for instance, page 92 of the Q for numbers and things like pages 48–49 for discussion of purpose etc.

2. And then some, since your revolvers are probably underpriced versus buying CDS.

3. Of course the person who knows is Lisa Pollack, who points out that hedge fund skew traders like to trade skew in the 10y because its maturity matches closely with liquid 5-year corporate CDS, so you can buy protection on the CDX and sell it on single names and make money. The 5y, which JPMorgan is hypothetically buying in huge size, does not present a useful skew trade because the other leg is very short-dated (under a year) and so can’t be put on profitably. So hedge funds had no reason to complain about that. Alternatively, if your theory is not curve-trade flattener but buy protection on HY index and/or tranches, the absolute size there would be less and so would spark less complaining than the $100bn of protection written on the IG index.

4. Again: doesn’t work for curve trades, where the DV01 on the 10-year is [oops, 5x] that on the near-expiry 5-year! So maybe it’s not a pure curve trade, or if it is I can’t really explain it. This is the best explanation you’re likely to find. I’ll stick with the stylized explanation in the text because it’s stylized but I guess I find the curve-trade arguments, like, 70 percent persuasive. [Update: I’m coming around more to arguments that this was buy-HY-write-IG rather than a flattener but will basically remain agnostic.]