CHAPTER 3

Creating a “Star Chart”: Freezer-Paper Piecing Techniques

Congratulations! You have discovered an amazing gem that inspires you and created a composition that delights your heart. Now you’re ready to transform your design into a quilt using the powerful technique I’ve been using for over twenty years to make my own giant gem quilts: freezer-paper piecing.

I’ll walk you through each step of creating a mock-up of your design and transferring it to a full-size freezer-paper pattern. My husband refers to these patterns as my “star charts,” because he thinks they look like constellation maps. I love that analogy. I think that is an apt term to describe the patterns for our own divas, too! These patterns will help bring your own stars to life.

Not only will you learn about each step of the process in this chapter, you’ll have the chance to practice them, too. I have created a small gem quilt project for you to work on as we move through each step of the process. After the description of each step, we’ll apply it to the sample project so you can put the concepts into practice. The sample project, Lovely Laurie, is inspired by a beautiful Mozambique purple garnet from the collection of Mayer & Watt (as photographed by Geoffrey Watt).

You’ll find the Mozambique Purple Garnet design mock-ups in the appendix.

Mozambique purple garnet

Photo by Geoffrey Watt (Mayer & Watt)

Overview

1. Create a mock-up of your final design using an appropriate ratio between mock-up and final quilt.

2. Trace the major facet lines on the mock-up.

3. Draw horizontal and vertical grid lines on the mock-up. The width between your grid lines is determined by the ratio between the mock-up and the final freezer paper you select.

4. Assemble the full-size freezer paper using double-sided tape to join the edges of the paper together.

5. Draw horizontal and vertical grid lines on the freezer paper with an erasable pencil. The width of your grid lines is determined by the ratio between the mock-up and the final freezer paper you select.

6. Draw major facet lines on the freezer-paper chart using a ballpoint pen or other permanent writing tool. Consult the mock-up to determine line placement.

7. Erase the horizontal and vertical grid lines on the freezer-paper chart.

8. Draw lines inside each major facet on your freezer-paper chart to replicate the shards of light and color, using your mock-up as your guide.

9. Identify the hues and progressive values of your design and assign each an alphanumeric code.

10. Select fabrics that correspond with each color code.

11. Create a color key that includes the alphanumeric code and a snippet of its corresponding fabric taped or pinned next to it.

12. Assign a color code to each shard on your freezer-paper chart using an erasable pencil (in case you wish to make changes later.)

13. Assign a unique identifier code to each shard within each major facet on your freezer-paper chart.

14. Place hash marks in a random manner on each line segment on your freezer-paper chart. Use a different color pencil or pen.

15. Make a copy of the freezer-paper chart using your home printer or a large-format printer at a copy shop or reprographic shop. (Reprographics is a blanket term encompassing multiple methods of reproducing content, such as scanning , photography, xerography, and digital printing. I use it, however, to refer to shops that specialize in copying very large images, such as architectural blueprints. Reprographic shops often charge far less for a large-format print than a regular copy shop.)

16. Reassemble the freezer-paper chart with double-sided tape as needed. Assemble the paper copy if necessary and place it next to your work area.

17. Assemble business-size envelopes or plastic baggies, and write a color code on each one.

18. Cut up your freezer-paper chart with a rotary cutter and ruler.

19. Sort freezer-paper pieces into envelopes or baggies by color code.

Introduction to Sample Project: Mozambique Purple Garnet

Finished block: 18˝ × 18˝

This beautiful Mozambique purple garnet from the collection of Mayer & Watt inspires our sample project. I love her marvelous purple and pink hue, as well as the great value contrast across her facets. The hexagon cut will be fun to piece, too. I’ve completed the first three steps of the process for you.

I’ve created the mock-up, which you will find in the appendix.

I’ve traced all the facet lines, as well as the interior cuts of light.

I’ve added the horizontal and vertical grid lines.

At the end of each step, I’ll walk you through the decisions I made as I selected and created the mock-up. When we get to the point of assembling the freezer paper, selecting colors, and coding the star chart, you’ll get to do all those steps right along with me. The directions that I provide result in an 18˝ block that you can use to make a mini-quilt or pillow.

SAMPLE PROJECT TOOLS

Freezer paper: 18˝ wide or precut sheets, either brown or white color (Freezer paper is a paper product used by butchers and crafters. It is available in 15˝ and 18˝ widths and as precut sheets. It is also available in some areas in brown and white colors. One side of freezer paper appears as a regular paper surface that you can write on; the other side is coated with a waxy substance. This waxy coating is what allows it to adhere to fabric without leaving a residue. Please note that freezer paper is not the same thing as wax paper or parchment paper.)

Regular erasable pencil

Colored pencil in a light color: Light green, pink, or blue

Eraser

Fine-tip ink pen or permanent marker

Double-sided tape

18˝ ruler and smaller 6˝ or 9˝ ruler, each with ¼˝ measurement

Highlighter pen (for example, yellow or pink)

Hand-held correction tape dispenser, like Bic Wite-Out EZ Correct (Do not use liquid correction fluid.)

Rotary cutter (2 cutters if you prefer using a different rotary cutter for paper and fabric)

Rotary mat

Home printer for copying final freezer-paper template (Or take freezer-paper template to a local copy or reprographic shop.)

Business-size envelopes or plastic baggies: 6

Iron

Basic sewing supplies (scissors, pins, seam ripper)

Tweezers

Fabric marking pencil(s) to mark on dark and light fabric

Basic sewing machine

SAMPLE PROJECT FABRICS

I noted the Painter’s Palette Solids from Paintbrush Studio Fabrics that I used below. A fat eighth measures 9˝ × 20˝–22˝ and a fat quarter measures 18˝ × 20˝–22˝.

White: Fat eighth or ⅛ yard (PPS 121-000 White)

Light pink: Fat eighth or ⅛ yard (PPS 121-018 Petal)

Light dusty pink: Fat quarter or ¼ yard (PPS 121-024 Orchid)

Medium dusty pink: Fat quarter or ¼ yard (PPS 121-152 Clematis)

Medium purple: Fat quarter or ¼ yard (PPS 121-027 Purple)

Dark purple: Fat eighth or ⅛ yard (PPS 121-080 Amethyst)

Black: ½ yard (PPS 121-004 Ebony)

Backing and binding: 1 yard (for 18˝ × 18˝ quilt)

Batting: 22˝ × 22˝

Create a Mock-Up

Your design is beautiful! You’re pleased with the composition and can’t wait to transform it into a quilt. The next step is to create a small mock-up of your final design. This step is mandatory if you’re going to transfer the design to freezer paper using the grid technique described in detail below. However, creating a mock-up is valuable even if you’re going to use a digital projector to project the image directly onto the freezer-paper template.

Plan the Mock-Up

I find that I get the best results when I print out a mock-up of my design (a close approximation to the appearance of my final quilt). In the mock-up, I need to be able to identify the facets that will serve as my blocks and trace their outlines with a pen or pencil. In addition, the mock-up must also help me identify the shards of light and color that intersect each facet.

How large should the mock-up be? Since I print out my mock-ups on my ink jet printer, they can be no larger than the narrowest margins of an 8½˝ × 11˝ sheet of paper.

I typically create mock-ups that have a ratio to my final quilt of one inch (1˝) to one foot (1´). In other words, if I want my final piece to be 6´ wide and 4´ tall, my mock-up must be 6˝ wide and 4˝ tall.

However, your work may be smaller than mine, and so a 1˝ (mock-up) to 1´ (freezer paper) ratio may result in a mock-up that’s just too small to be useful. For example, if you are planning your final quilt to be 3´ wide and 4´ tall, a 3˝ × 4˝ mock-up might be too small to capture the details of the facets and light that you’ll need to create your larger piece. Try creating a mock-up that is twice that size: 6˝ × 8˝. Your ratio would then be 1˝ (mock-up) to 6˝ (freezer paper).

In general, I coach students through the process of creating a mock-up plan in a way that doesn’t get them too side-tracked by the math.

Use these guidelines for good results:

• Plan the width of your mock-up to be a whole number: 4˝, 6˝, or 8˝.

• Divide your mock-up into a number of segments that is easily divisible by the total width of the design. Remember: You can always divide your mock-up into 1˝ segments for easy planning.

A few examples:

• If your mock-up is 4˝ wide, divide it into 2 columns that are 2˝ wide.

• If your mock-up is 6˝ wide, divide it into 3 columns that are 2˝ wide.

• If your mock-up is 8˝ wide, divide it into 4 columns that are 2˝ wide.

• Draw vertical lines onto your mock-up the desired width apart (based on your choice above).

• Now draw horizontal lines onto your mock-up the exact same desired width apart (based on your choice above). It’s okay if you have partial columns at the bottom; we’ll calculate that into the size of your freezer-paper chart.

• Determine the width of your final quilt.

• Divide that width of your quilt by the number of columns that you chose for your mock-up. Example: If you segmented your mock-up into 4 columns, divide the width of your quilt by 4. That calculation will be the width of your grid lines, both vertical and horizontal.

• If the final width of the quilt will be 4´ and you divided the mock-up into 4 columns, the width of the freezer-paper grid lines will be 1´. (4 ÷ 4 = 1)

• If the final width of the quilt will be 5´ and you divided the mock-up into 4 columns, the width of the freezer-paper grid lines will be 1¼´. (5 ÷ 4 = 1.25)

• If the final width of the quilt will be 6´ and you divided the mock-up into 4 columns, the width of the freezer-paper grid lines will be 1½´. (6 ÷ 4 = 1.5)

Your mock-up could be as simple as a printout of the gem(s) you wish to use in your design pasted onto construction paper and cut to the desired size. This is how I created the mock-up for many of my giant gems.

You can also create a mock-up using a graphic design application like Adobe Illustrator (which requires a monthly subscription) or a free online version like Canva.com. These apps allow you to select the size of your starting “canvas” so that you can print it out to the desired size. The power of these apps is that they allow you to upload images and use them to create a composition. They also allow you to add background color, line, and shape elements to your design.

Project: Create a Mock-Up

I have created the mock-up that will serve as your guide for the final quilt (see the appendix). You can use the 6˝ × 6˝ mock-up to create any-size quilt you wish. Whether it be 6˝, 18˝, 48˝, or even larger, we’ll discuss how to convert the mock-up to the quilt size you want.

The composition of our mock-up is straightforward. It’s a portrait of our beautiful Mozambique purple garnet, with all the edges within the boundaries of the quilt. The six-wedge design is familiar to many quiltmakers, and the straight seamlines make for easy piecing.

Trace the Facet Lines onto the Mock-Up

Once you’ve printed out the mock-up, take a pencil and trace the outlines of your major facets.

1. For example, if your inspiration is a round brilliant cut, search first for the kite facets. Find at least one and extrapolate from that one. Your gem might not have perfectly delineated facets. Draw them in where you think they belong. Remember, that if your gem image is tilted in any way, the top points of the kite facet might be beyond the gem edge. That’s fine!

2. Once all your kite facets are holding hands around the circle, connect their “toes,” the points that face toward the center of the gem. You now have identified your table, star, kite, and upper girdle facets.

3. Look deep into the table facet and decide how you’re going to piece it together. Find—or create—one major line that divides the table facet into 2 halves. If you feel those 2 facets are manageable as separate sections, you can leave it at that. If, however, the 2 table facets will end up having more facets than you care to track, further divide each half by finding the lines that run through it.

Sometimes you need to take some artistic liberties with the shards of light and color to corral them into a quilt pattern. Don’t be shy or hesitant about it—this is your diamond. There is no right or wrong answer. Have fun!

Keep in mind the importance of offsetting your facet lines just a bit to prevent converging seams. Your eye “sees” what it wants to see. My first solitaire had 12 seams converging at the central point. It was a mess! I quickly learned that I could offset the seams at any one point. Again, light doesn’t follow quilters’ rules!

I generally trace only the major facet lines on my mock-up. If I were to trace all the lines delineating the color and light shards, my mock-up would get way too busy and overwhelm me. The main purpose here is to help you identify the major blocks. We’ll deal with the smaller pieces on the freezer paper.

Project: Trace the Facet Lines onto the Mock-Up

While I typically trace the facet outlines of my mock-up with a regular pencil or pen, for this particular mock-up, I used Adobe Illustrator to draw the facet lines onto the image. I wanted to do this to show how you can modify the lines from the original gem (see the appendix).

Instead of drawing our mock-up to include all the facets within this lovely gem, I decided to take some artistic liberties. I offset a few of the lines separating the light and color to make it easier to piece, and I did not delineate every single change in color and value—best to keep our first project together relatively simple.

The final mock-up is one that I believe will reflect the loveliness of the original gem and yet result in a quilt block that will be fun to piece and will delight your eyes.

Sample project facets

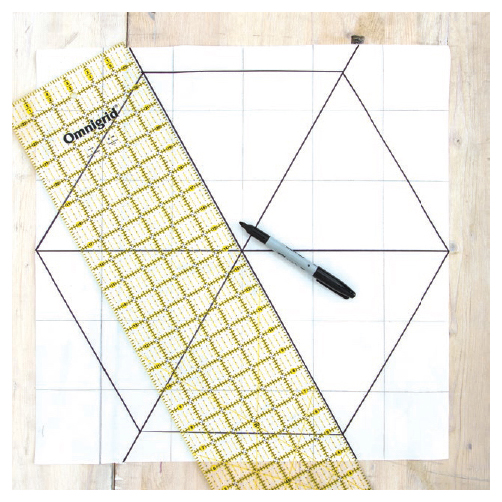

Draw Grid Lines on the Mock-Up

Now you’re ready to place your grid lines over top of your facet lines. Using a different color pencil, trace the lines that will create the number of columns and rows that you determined earlier.

Why a different color? With all these lines and color shooting through your mock-up, it can get pretty confusing trying to figure out which are facet lines and which are grid lines. Using a different-color grid line provides a visual clue that it is indeed a grid line that you’re looking at and not a facet line. This becomes critically important as you begin to replicate the facet lines on the freezer paper.

Use light pencil to trace grid lines on mock-up.

Project: Draw Grid Lines on the Mock-Up

I used Adobe Illustrator to draw light yellow grid lines in 1˝ intervals over the mock-up. Always keep an eye out for the possibility that a grid line might overlay a facet line. In this case, the central horizontal line of our mock-up is obscured by the central horizontal grid line (see the appendix).

Create a Full-Size Freezer-Paper Chart

Assemble the Freezer-Paper Chart

You’re now ready to prepare your freezer-paper chart. Cut lengths of freezer paper to size according to the final dimensions of your quilt. Freezer paper comes in rolls that are 15˝ and 18˝ wide and in precut 8½˝ × 11˝ sheets. I typically use the 18˝ width.

Place double-sided tape on the edge of one length of freezer paper. Carefully overlap the tape with the back of the edge of a second length of freezer paper. Be careful to keep the edges of the freezer paper sheet parallel. If you used 2 pieces of freezer paper 18˝ wide, you now have a sheet that is approximately 35˝ wide. (The 2 freezer-paper sheets 18˝ wide overlap by about ½˝, reducing the total width of the combined 36˝ by approximately 1˝.)

Repeat with additional freezer paper until you have created a sheet the full size of your final quilt dimensions.

TIP

Use Precut Freezer Paper

C&T Publishing offers Quilter’s Freezer Paper Sheets as an alternative to commercially available rolls. The 8½˝ × 11˝ sheets work well with our sample project. You will need a total of 6 sheets for the Mozambique Purple Garnet project.

1. Place double-sided tape on the non-waxy side of the sheet’s lower 8½˝ edge.

2. Carefully overlap the upper edge of another sheet of freezer paper to cover the double-stick tape. (The regular paper side of each freezer-paper piece should be right side up.)

3. Repeat to create 2 more pairs of freezer-paper sheets.

4. Place double-sided tape on the long edge of 1 pair of freezer-paper sheets.

5. Carefully overlap the long edge of another pair to cover the double-stick tape. (The regular paper side of each pair of freezer-paper sheets should be right side up.)

6. Add the third pair of freezer paper sheets to the first 2 using double-stick tape.

7. Draw an 18˝ × 18˝ square on your joined freezer-paper sheets.

8. Once you’ve completed your chart codes, gently pull apart the freezer paper to reveal the double-stick tape.

9. To make a copy of your chart, place each separated 8½˝ × 11˝ sheet facedown on your home printer and select Copy.

10. Once all copies have been made, reattach the freezer-paper sheets and the regular paper copies with double-stick tape according to your original design.

Project: Assemble the Freezer-Paper Chart

Using 18˝-wide freezer paper, cut an 18˝ length from the roll. We’re going to use a ratio of 1˝ to 3˝ to enlarge our 6˝ square mock-up to an 18˝ block. This fits perfectly with an 18˝ freezer-paper length, though you can also use precut sheets of freezer paper (see Tip: Use Precut Freezer Paper).

Using a Digital Projector

I purchased a digital projector a few years ago to project images of my mock-ups directly onto freezer paper. I have found that the enlarged images are blurry, and the color isn’t as true as I would like. In the instances when I’ve used the digital projector, I’ve always printed out the mock-up and referred to it throughout the process. Then why use a digital projector? It simply saves you the step of tracing the grid lines onto your mock-up and your freezer paper.

When using a digital projector, be mindful of cords. You don’t want to hurt yourself or your projector by tripping over cords and sending your projector crashing to the floor. I recommend taping the cords to the floor to keep them in place and reduce tripping hazards.

Using the Grid Technique

The grid technique forces me to truly study my design and make changes to the design on the fly if I need to. But I suppose the real reason I enjoy this technique is that I love maps. This is simply a mapping technique that allows me to lay down the lines of my gemstones using the coordinates created by the horizontal and vertical grid lines.

TIP

On or Off the Wall?

Because my freezer-paper charts tend to be large, they are unwieldy to produce on a tabletop. As a result, I prefer to tape my large freezer-paper template to my design wall before adding the grid lines and facet lines. A 4´ carpenter’s bubble level helps to draw perfectly horizontal and vertical grid lines.

You may prefer to work with more manageable-sized freezer-paper charts, so you would more likely be able to add grid lines and facet lines working on a table surface.

Using an erasable pencil, lightly draw horizontal and vertical lines in the desired widths on your freezer-paper template. Draw on the side that looks like regular paper—the side you can easily write on. Do not draw on the waxy side. The waxy side will be facedown on your fabric. Why use an erasable pencil? Because once you’ve drawn your facet lines over the grid lines, you’ll erase the grid lines to reduce the visual noise on your freezer-paper chart.

Add grid lines to freezer-paper chart with erasable pencil.

Transpose the Major Facet Lines of Your Design to the Freezer-Paper Chart

Using a non-erasable pen or marker, transpose the major facet lines of your mock-up onto the freezer paper.

If you’re using a digital projector to project your mock-up on the freezer-paper chart, adjust the size of the projected image by moving the projector closer or further away from the wall until the image fits the freezer paper. Adjust the focus until the image is sharp. Be sure to tape the projector power cord to the floor or otherwise protect it so that you don’t stumble over it as you trace the facet lines of your image.

I recommend having a physical copy of your mock-up available to you during this process. The image projected on the wall can be fuzzy in areas and a physical mock-up will help clarify line placement. This printed mock-up will also be helpful when you start adding color codes to your freezer-paper chart.

TIP

Use Non-Erasable Pen or Marker to Draw Facet Lines

You must use a non-erasable pen or marker to draw facet lines, because in a few minutes you’ll be erasing those light pencil grid lines. You don’t want to damage your lovely facet lines as you’re getting rid of the grid lines!

If you’re using the grid technique, use the horizontal and vertical grid lines as reference points to determine where to place your facet lines on the freezer-paper chart.

1. To get started, take a look at your mock-up. Find the major “through line” of your design—the one line that splits your design into 2 parts—if you have one. Otherwise, select a kite/bezel facet to start with.

2. Once you’ve identified the first line, you’ll transpose that line to the freezer-paper chart. Find its origination point on the freezer-paper chart grid. Where is it located in reference to the closest grid lines?

In our Mozambique Purple Garnet project, the first through line on my mock-up is the horizontal line that splits the image into perfect halves. That’s pretty easy to spot and transpose to the freezer paper.

So, let’s look for the next through line. I’m going to use the intersecting line that originates at the top left of the design, intersects the design at the dead center, and terminates at the lower right edge of the design.

How would you describe the origination point of this line? It appears to be about one-third of the way across the top of the second column. Next, I’ll find the corresponding point on my freezer-paper chart, about one-third of the way across the second column from the left. I’ll place a mark there with my ballpoint pen or permanent marker. (By the way, what is ⅓ of 3˝? 1˝! If you want to measure 1˝ to place your mark, feel free. But you can certainly eyeball the placement of your mark for now. We can adjust later.)

3. Now look for the line’s termination point on the mock-up. Where is it located to the closest grid lines? In this example, the termination point on the mock-up appears to be about two-thirds of the way across the fifth column. So, I’m going to find the corresponding position on my freezer-paper chart—about two-thirds of the way across—and make a mark with my pen or marker. (Again, what’s ⅔ of 3˝? 2˝! If you want to measure, feel free. Once more, it’s okay to eyeball the placement of the termination mark.)

4. Now let’s see where that line intersects the grid lines on the mock-up. In this case the line intersects the exact center of our design. So, I’m going to go back to my freezer paper and connect my origin and termination points with a straight edge or ruler. Does the edge of the ruler intersect the exact center of the freezer-paper grid lines? If not, simply adjust your ruler so that the line runs through the intersecting grid lines at the dead center of your design. Are you happy with it? Once you’re satisfied with that line, use a pen or permanent marker to scribe the line on the freezer paper.

Continue using this process of using the start and end points of lines on your mock-up to estimate and scribe lines in your freezer-paper chart. Again, keep in mind that you can offset your facet lines if you want to prevent lots of seams from converging at one point. I’ll say it again: Light does not conform to quilters’ rules! You can move those little lines any which way you want. This is your gemstone.

TIP

Modifying Lines Already Drawn

If you decide to change a facet line on your freezer paper, you can easily do this by covering it up with correction tape. Hand-held correction-tape dispensers are a wonderful invention. I used to eliminate unwanted lines by placing squiggle marks through them, but this ended up with lots of visual noise on my freezer-paper chart. Correction tape solves this problem. And you can iron over correction tape. On the other hand, please don’t use correction fluid. It will ruin your iron.

Use correction tape to hide unwanted facet lines.

5. Once all your major facet lines have been drawn on your freezer paper, erase those lightly penciled grid lines.

Project: Transpose the Major Facet Lines to the Freezer-Paper Chart

1. Using an erasable pencil, lightly draw lines 3˝ apart horizontally and vertically on your freezer-paper template.

2. Use non-erasable pen or marker to draw facet lines.

• Find the major through line of your design on your mock-up. The through line is the line that splits your design into 2 parts. In our case, it is the center horizontal line that splits the design in perfect halves.

• Draw the first line on the freezer-paper chart. This one is going to be easy because it follows exactly the center horizontal grid line (the third horizontal line from the top.) Take your ruler and pen (or permanent marker) and draw a line over the center horizontal grid line.

• Find a through line that splits the top half of your mock-up into 2 sections. This isn’t so easy, is it? That’s because there are no lines within our lovely hexagon-shaped Mozambique purple garnet that split the top and bottom halves into 2 sections. So we get to create them!

Since I like the energy of angled lines, I’m going to create a couple of through lines by extending the central intersecting facet lines all the way to the upper and lower edges of the mock-up. This will create 6 sections that can be easily coded and pieced.

• Transfer intersecting lines to the freezer paper. Clearly both lines intersect the exact center of the mock-up. All we need to do is find the origination and termination point of each line. And this is all just guesswork—nothing scientific about it.

Let’s look for the origination point of the line that extends from the top left to the lower right on your mock-up. It originates at the top of the mock-up near the halfway point of the second column from the left—but not quite.

On the top edge of your freezer-paper chart, locate the halfway point of the second column from the left and then move your pen slightly to the left. Make a mark.

Now drop your ruler onto the freezer paper so that it aligns with the mark you just made and also runs right through the center point of your grid. Does the termination point look like it lands on your freezer paper at about the same place as it does on the mock-up?

If not, pivot the ruler slightly, keeping it aligned with the center point of your grid, and draw your line. See how easy that is? It’s your gem. That line can be any angle you want it to be.

Do the same thing with the intersecting line that runs from the top right to the lower left. Drop a mark where you think the line originates. Drop a ruler so that it aligns with both your mark and the center point of the grid. Do you like where it lands at the bottom of your freezer paper? If not, pivot the ruler, keeping it on the center point of the grid, and draw your line.

Voilà! You have 6 major sections that you can now begin to slice into pieces.

• Draw the edges of the garnet on your freezer-paper template. Take a look at the horizontal line at the top of the mock-up between the 2 intersecting section lines. It’s about halfway between the grid lines of the top row. (Actually, it might be slightly closer to the top edge than the first grid line.)

Math whizzes might be inclined to measure the actual distance of the line between the upper and lower edge of the column, and to multiply the measurement by 3. This will give you the precise point to place your horizontal line on the freezer paper. If that gives you goosebumps, do it! But for us non-math geeks, remember: Precision isn’t a priority with these gems! I dropped my line in the illustration about halfway between the top and the first grid line. And it will be perfect.

Do the same with the horizontal line at the bottom of the mock-up between the 2 intersecting section lines. Draw your line with your permanent pen.

Now that you’ve located the top and bottom edge of the gem, simply connect the dots to get the remaining 4 edges.

• Highlight the edges of the major sections and the outside edges of your freezer paper with a colored highlighter. This is another visual clue to help you know which edges should be placed along the grainline to help prevent stretching during the sewing process.

Draw major facet lines on project freezer-paper chart using mock-up as your guide.

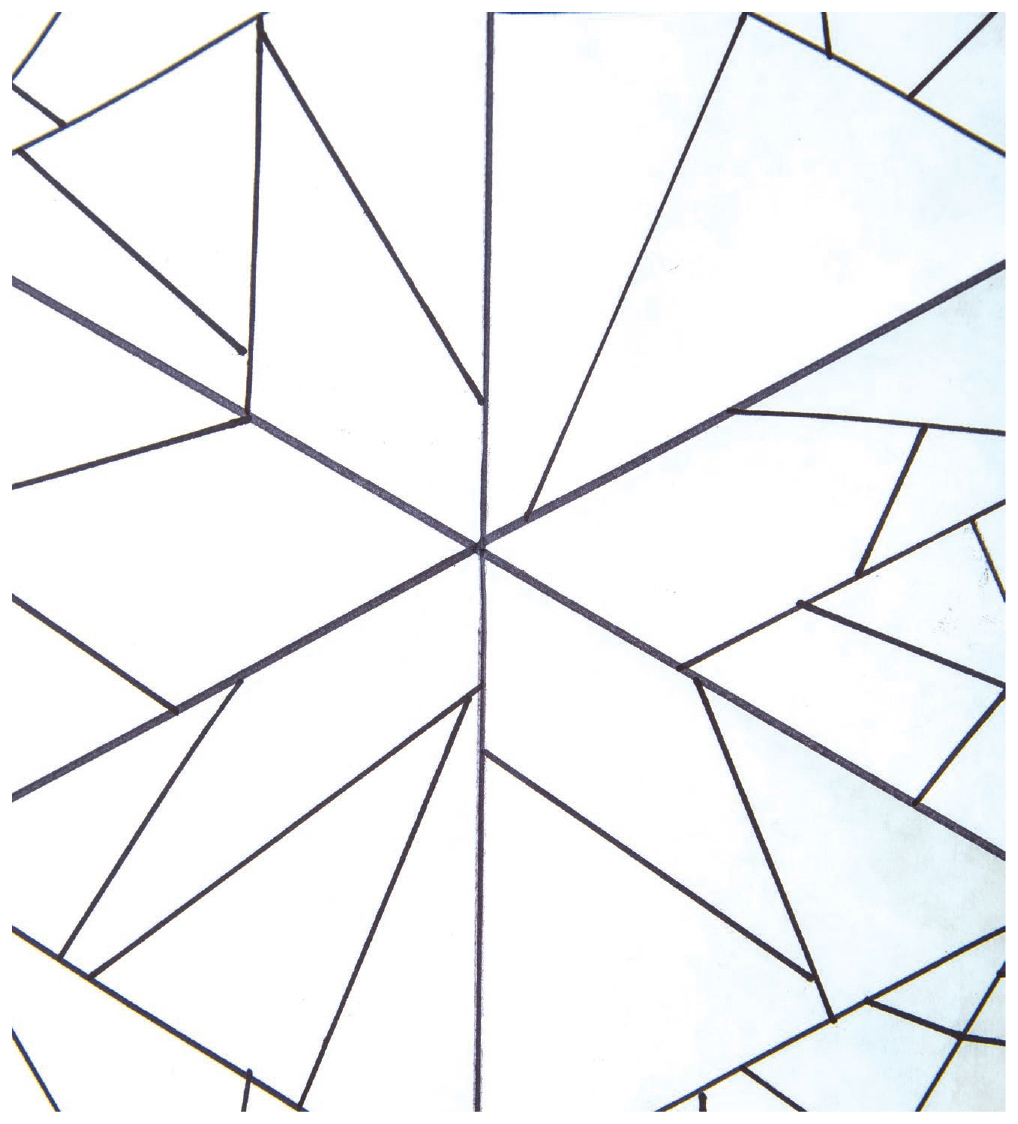

Capture the Light Within the Facets on the Freezer-Paper Chart

With the outlines of your major facets now scribed on your freezer paper and with the grid lines gone, you can now start to carve up the interior of those facets with shards of color.

Working with one section at a time, segment the facet according to the shapes you see within your mock-up. I like to work with a magnifying lens close by so that I can dive deeper into the facet.

Here are a few pointers to keep in mind when segmenting the interior of the facets:

• Keep it simple on your first attempt. Don’t worry about capturing every tiny shard and angle of the light. Instead, focus on capturing the major changes in color and value. You may see several colors that are close in value; feel free to combine those into 1 large piece.

• Pay attention to changes in value contrast. Capturing the darkest darks and the lightest lights will pay visual dividends. When you divide a section that will eventually become a light or white area, make a small notation in it (for example, “white” or “very light”) This will be a great help when you go back over the facet to assign color codes.

• Change Y-seams to y-seams. If you see several shapes of color and light coming together that would result in a Y-seam, change it into a Y-seam. No need to make this more complicated than it needs to be. No one will know that you made the change as they’re looking at your gorgeous gem.

• Offset your seams. If you see several facet lines colliding together in one spot, offset the lines. Again, there’s no need to make piecing more difficult than it needs to be. Light bounces around gems in a million different ways and, once more, light doesn’t conform to quilters’ rules.

• Mix it up with different shapes and sizes. I like to see lots of contrast in my work, whether it is in color, shapes, or piece sizes. When you have a large piece surrounded by smaller pieces, it makes for a more interesting composition.

Example of different shapes and sizes of facets

• Forget about symmetry. You’re going to get sick of me saying this: Light doesn’t conform to quilters’ rules! Light rarely obeys the laws of symmetry either. Some students ask me if they need to have the same number of pieces in each facet. No! Your mock-up is your guide. In some cases, an entire facet might be a single piece of fabric. This often happens when you find a gem that is reflecting oblique light off of an entire plane of a facet. Perfectly normal—and gorgeous!

• Manage washes of color. In some cases, you will see the boundaries of colors clearly defined in your gem. But in some pieces, you’ll see a gradual wash of color. How you handle these washes within a single shard of light is partly dependent on the type of fabric you plan to use.

If you have decided to use solid fabrics, you can create the illusion of a wash by segmenting the large piece into smaller pieces and assigning color codes in a gradual value progression. If you have selected fabric that includes gradations of color—such as commercially available gradients, hand-dyed fabric, or hand-painted fabric—you can create the illusion of a wash by keep the piece whole and using a special color-coding technique I describe in the next section.

Project: Capture the Light Within the Facets on the Freezer-Paper Chart

What a gorgeous hexagon you’ve got there! You’re now ready to draw the lines that make up the interior angles of light and color within each facet.

Working wedge-shaped section by wedge-shaped section, transpose the lines on the mock-up to your freezer paper. Use the same techniques you used to estimate the origination and termination points of the major facet lines. I obviously didn’t follow the actual lines of the original Mozambique purple garnet to create our mock-up. Therefore, you don’t have to follow mine. This is your gem! (You’re going to get sick of me saying that, aren’t you?)

Feel free to subtract lines from the design to simplify or add lines for more of a challenge. However, remember that more divisions mean smaller pieces. If you can handle small template pieces fairly easily and you are a confident piecer, slice it up! However, if this is your first attempt at freezer-paper piecing, you might want to stick with my design or even leave some of the lines out.

If you draw a line and realize it should have been placed elsewhere, use your correction tape to cover up the line.

Here is what your freezer-paper chart could look like. Label the top of the freezer-paper chart. Erase the grid lines from your freezer-paper chart.

Shards of light and color within sample project

Coding the Freezer-Paper Chart

The coding system I describe here is all about providing you with visual clues that you can use to sew these little pieces back together. Imagine every piece of a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle dumped onto the table. That’s what your freezer-paper templates are going to look like sitting on your work surface after you’ve cut them out of fabric: shards of light and color tumbling across the table. Most people will look at that amazing pile of color and wonder, “How in the world am I going to put these back together in exactly the right order?” You, on the other hand, will smile confidently and know you’ve got this. You know the codes.

Each piece you’ve drawn on your freezer-paper chart will receive 2 codes and a set of registration marks called hash marks. The first code describes its color. The second is its unique identifier, providing clues about its position in the entire gem. The third set of marks help guide your piecing as you sew each set together.

I typically use a letter followed by a numeric modifier for the color code (for example, Y1, Y2, and Y3 for light, medium, and dark values of yellow), while the unique identifier is always made up of 2 digits separated by a hyphen (for example, 1-15, 1-16, and 1-17). The reason one code is a letter and the other code is a number is to distinguish one from the other. If both codes were numerical, my head might explode when looking at the chart. The potential for error skyrockets.

Color Codes

I prefer to work on the color codes first before assigning unique numerical identifier codes. Determining how color flows across the facet is subject of interpretation and therefore change. As a result, I routinely add or subtract pieces from a facet after reviewing the color distribution of the mock-up a second or third time. If I wanted to make changes to color assignments after already completing the numbering sequence, I could very well end up with a hot mess. And I have.

I described the process of selecting fabrics to create your color palette in Chapter 1. I’ll review some of those pointers here and weave them into the larger task of creating a color key and assigning color codes to each piece in the gem.

1. Study the mock-up (or original gem image) to identify one or more basic hues found in the gem. (Remember: Hue is a basic color identity such as blue, red, yellow, green, and combinations thereof. They are the colors that ring the outside of a color wheel.)

2. Select the basic hues present in your gem. Keep it simple and start with a single hue for your first project.

3. Identify the range of tints or shades of your basic hue(s) in your mock-up or original gem image. Let’s keep it simple for the first project. Try to identify no more than 2 tints and 2 shades surrounding your basic hue. These 5 values, along with pure white and black, will give you a strong palette to work with. With 5 values in 1 hue, can you see how complex the coding could become if you decided to work with 3 or more hues? With 3 hues, you could easily have 15 colors to choose from, plus black and white. That can result in option anxiety, and ultimately, frustration and paralysis.

4. Assign codes to each of your values. I use a letter to signify the hue and modify it with a number based on its value. For example, if I were working on an emerald and selecting an array of green values, I would use the letter “G.” In my world, the lightest value always receives the modifier “1” while the darkest values receive higher numbers. Thus, I might create a set of codes that look like this:

G1 = Pale green (light celery)

G2 = Light green (mint)

G3 = Medium green (kelly)

G4 = Dark green (leaf)

G5 = Deepest green (deep forest)

W = White

BLK = Black

When assigning letters to your color codes, be careful to use unique letters for each hue. This is why I use BLK to signify black. If I’m working with a sapphire and have a range of blue fabrics, I want to be sure I can distinguish between the facets coded for blue and those coded for black. Both colors start with B.

In my early work, and in some cases in my patterns today, I use a unique letter of the alphabet for a specific swatch (A, B, C, D, and the like). This is a very helpful coding solution when I am creating a pattern in multiple colorways. For example, I created Elizabeth (the first of my Diamond Divas series) in blue, pink, yellow, and neutral. I could print 1 copy of the pattern using the alphabetical system rather than recoding everything in B1, B2, B3, and so forth for the blue colorway, and then create an entirely different pattern coded for R1, R2, R3, and so on for the reddish-pink colorway.

In the long run, choose the coding system that works best for the way your brain works!

5. Select color swatches to coordinate with your codes. If you’ve already placed your fabric in a value progression, it will be easy to accomplish.

6. Create a color key by writing the codes on a sheet of paper. Cut a small snippet of fabric from your swatches and, using double-sided tape, pins, or glue, secure the snippet of fabric next to its code. I also write the name of the project and the date on the top of the paper for the record.

7. Using an erasable pencil (in case you want to make different design choices later), assign color codes to your pieces, starting with the white and black pieces first. Work through one facet at a time in a systematic fashion.

Close-up of color-coded chart. Assign color code to each piece.

Once you’re confident that all the white and black pieces have been coded, select the next lightest color code and work your way through the design, identifying each piece.

After the lightest light is completely coded, move to the darkest dark color code. After awhile, you may notice that your white and lightest light pieces are right next to your black and darkest dark pieces. This is what gives your gem its brilliance!

Continue working through your color values until all pieces are coded.

TIP

Coding for Sweeps of Color

You may be working with a gem that has a flow of color across a single piece. If you have decided to use a gradient fabric or a hand-painted or hand-dyed fabric, decide on the range of codes that you see in the fabric swatch. Attach snippets of this area of the fabric to your paper color key. When coding the piece that contains the sweep of color, place several color codes that correspond with the gradient and connect them with a squiggly arrow. This is my visual clue to myself that I’m dealing with a color wash.

Commercially available gradient fabrics limit how you can translate the sweep of color in a gem to the striation in the fabric. You have far more flexibility if you decide to hand-paint your own fabric (see Creating Light: Painting Fabric).

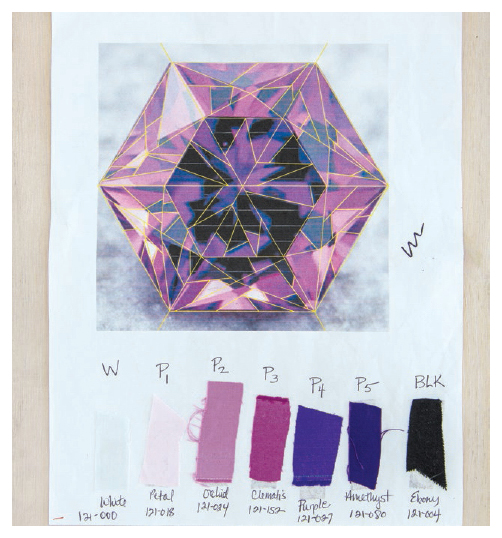

Project: Add Color Codes to the Freezer-Paper Chart

1. Identify the hues and values of your design and assign each an alphanumeric code. After studying the Mozambique purple garnet, I saw purple and light red (pink) hues.

2. Select fabrics that correspond with each color code. I dove into my stash of Painter’s Palette Solids by Paintbrush Studio Fabrics and began auditioning fabric. I selected a medium purple hue for my base color. I found my lighter values in stacks of pink and dusty pink swatches. The darker value was a single shade called Amethyst. I used the letter P for my main color code. See the sample project fabrics.

W —White

P1—Light pink

P2—Light dusty pink

P3—Medium dusty pink

P4—Medium purple

P5—Dark purple

BLK—Black

3. Create a color key (see the bottom left photo) that includes the alphanumeric code and a snippet of its corresponding fabric taped or pinned next to it.

4. Assign a color code to each shard on your freezer-paper chart using an erasable pencil (in case you wish to make changes later). Here’s an example of what your chart might look like.

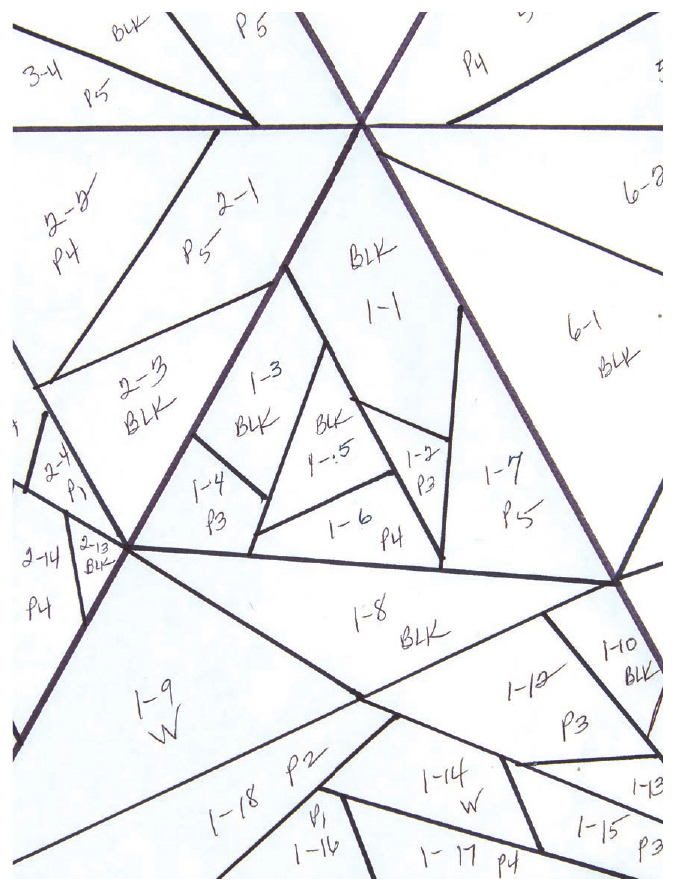

Unique Identifier Codes

The second code on each piece of your facets is its unique identifier. Each facet in your design should have its own unique code identifying its place in the design. No two should be the same. Think of it as the piece’s address within the gem. The strategic placement of these codes will also help you piece the facets back together exactly where they need to be.

I described the unique identifier coding system in Chapter 1. It involves 2 digits separated by a hyphen. Here are steps and suggestions for successfully coding your gem’s facets and pieces within those facets.

1. Identify the number of major facets in your gem. Assign each a section number. This is the first number in your 2-digit code. Working one facet at a time, label every piece in that facet with the first numeral and a hyphen following it. I like to use a different color pen to further differentiate between the codes.

2. Once you have coded each piece in a facet with its section number and hyphen, start at one side of the facet and begin adding the second digit: 1-1, 1-2, 1-3, 1-4, and so on.

When numbering facets, it’s important to keep your piecing strategy in mind. This is what I like to call the “Piece Plan.” You are going to be sewing these pieces back together in units. Place adjacent numbers next to one another. If, however, you want to be sure to signal that you’ll be starting a new set of units—meaning you won’t sew one piece to an existing pair—consider placing that code a distance away from the last one in the series. Look at the example below. This numbering system provides another visual clue that you are putting the right pieces together. If you reach for a new piece to sew to an existing set and its code is out of order, you are more likely to say “Aha! These two aren’t supposed to be sewn together right now. Let me find the right ones!”

Consecutively number pieces to be sewn together as 1 unit. Adjacent pieces that will not be sewn together should not be consecutively numbered.

3. Review your codes to ensure that you haven’t skipped a number. Remember the story of Pig #3 in Chapter 1!

4. If you find that you have indeed skipped a piece, no worries! You don’t need to erase all your codes and start over. If you are splitting the piece coded as “2-3”, add a lowercase a behind the “2-3”. Label the additional piece “2-3b.”

TIP

Tricky Codes

When all your freezer-paper pieces are cut apart, it’s very easy to mistake a piece coded “1-11” with a piece coded “11-1”. To prevent confusion, put a line under these particularly tricky codes. The same can occur with pieces coded “9-6” and “6-9”.

Project: Add Unique Identifier Codes to the Freezer-Paper Chart

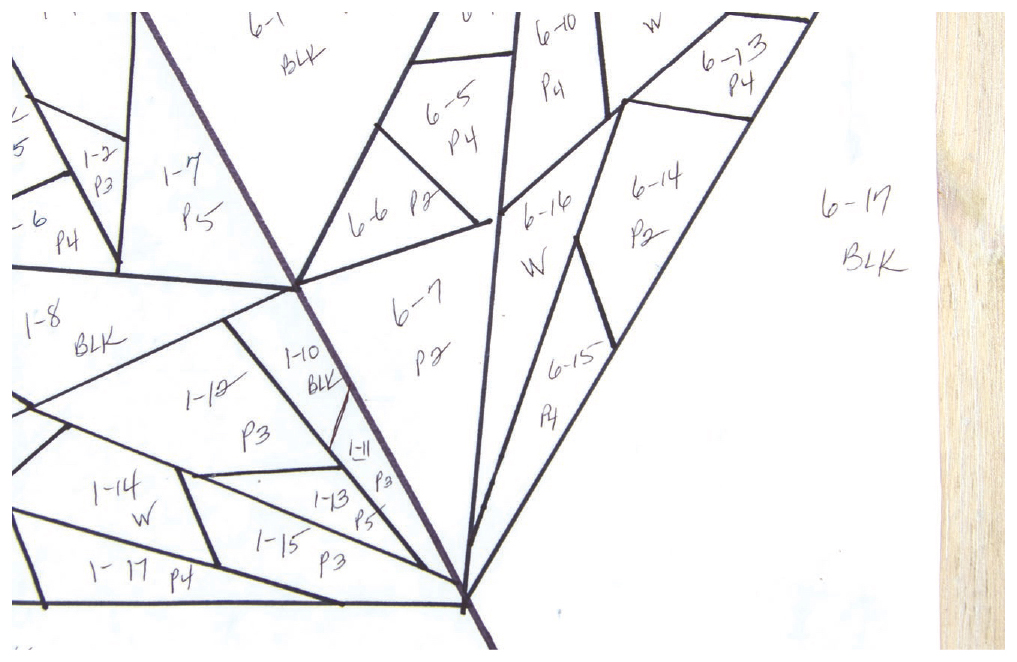

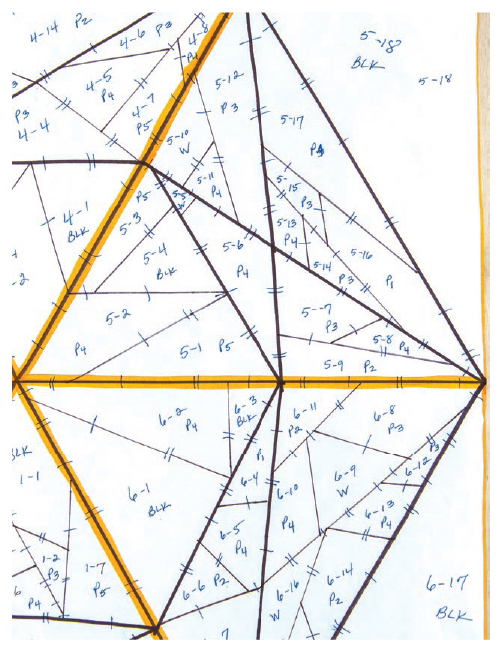

Assign a unique identifier code to each shard within each major facet on your freezer-paper chart. Here’s an example of how your freezer-paper chart could be coded.

Sample project with unique identifier codes

Hash Marks

Hash marks are the little slash marks that cross the facet (seam) lines of your pattern. You will come to love these little guys because they are confidence builders. They provide visual clues that confirm you are indeed piecing the correct 2 freezer-paper templates together, and they warn you when you’re not. Here are the important things to know about your new friends, the hash marks.

1. Consider drawing your hash marks using a colored pen that is radically different from the color you used to draw your seamlines. I use red or green. Why? After a while of drawing hash marks, I start to get distracted and skip areas. I’ve actually skipped an entire facet. How could I tell? There were gaps in the sea of green hash marks across my chart—yet another visual clue that my work wasn’t quite complete.

2. Place at least 1 hash mark on the segment of a line between 2 intersecting seamlines. If you can fit in 2 hash marks, do it.

Each line segment must have at least 1 hash mark.

3. Draw hash marks as perpendicular to the facet line as possible.

4. Be sure that the hash mark extends all the way across the facet line and extends into the piece on both sides of the line.

5. Start this process by selecting one of the long lines between your major facets. Work along the entire length of the line from its start to the end. Each place you see another facet line intersect the line you’re working on, that’s the start of a new segment; drop a hash mark or 2 there.

6. Don’t skip over tiny little line segments. These are the most important! Drop a tiny hash mark between 2 tight intersecting points, and you will thank yourself when the time comes to sew these pieces together.

Don’t forget to place hash marks in tiny line segments.

7. Distribute hash marks as randomly across the line segments as possible. You don’t want to automatically aim for the dead center of every line segment. For example, in one segment, place the hash mark one-third of the way between the 2 points; on the next segment, place the hash mark two-thirds of the way across the segment.

8. Randomize the number of hash marks in a set. Mix up the hash marks you draw, randomly alternating between 1 mark and a set of 2—or maybe 3—marks.

Why the emphasis on randomness? You will be sewing sets of freezer-paper templates together that have wonky shapes. There’s nothing about them that screams, “We belong together!” It’s easy to pick up 2 pieces that lie next to one another, but which should not be sewn together at that precise moment? You need a signal that you’ve picked up 2 pieces that don’t go together! Hash marks holler at you to stop if this is what you’re trying to do.

If you are holding 2 pieces that do indeed go together, the only thing that will match will be the seamline they share. And since you’ve drawn a hash mark—or 2 or 3—across that seamline they share, you will essentially be reuniting them. If the hash marks line up perfectly, you have a joyful reunion! That’s why you want to drop them across the seamline as randomly as possible; they will shout at you even louder if they don’t match up.

Project: Add Hash Marks to the Freezer-Paper Chart

Place hash marks in a random manner on each line segment on your freezer-paper chart. Use a different color pencil or pen. Here’s what the hash marks on your sample project could look like.

Hash marks on sample project

Copy the Freezer-Paper Chart

Congratulations—your star chart is complete! You have diligently placed all the visual clues you need to put this thing back together once it has been cut up. You’re almost ready to cut up the freezer paper into all its tiny little shards of light and color … but not quite.

Before you pick up your rotary cutter and ruler, you must make a full-size photocopy of the chart. No “ifs,” “ands,” or “buts.” This is a nonnegotiable step. You would never try to put a 1,000-piece puzzle together without the top of the puzzle box sitting next to you, would you? It would be a time-consuming, frustrating, and nearly impossible task. Same goes with trying to put together your freezer-paper templates without a paper copy to guide you. It would be a joyless undertaking.

If your chart is no larger than 8½˝ × 11˝, you can easily make a photocopy or scan your document and print out the results. If your chart is too big to fit onto the scanner bed, try folding it into even sections. Scan each section and name the file with a unique filename (such as Emerald 1, Emerald 2, Emerald 3, and so on). Print out the results and tape the sections together.

Since my charts are typically 5´ or more on any one side, scanning them on my home printer doesn’t work for me. Instead, I use the self-service large-format printer at my local copy or reprographic store.

Large-format printers can print images up to 36˝ in width and an unlimited length. They typically have 2 widths of paper rolls to choose from: 24˝ and 36˝. Copies are priced by the square foot. Therefore, if your chart is under 2´ in width, be sure to center the original between the 24˝ marks to get the best pricing.

If your chart is under 36˝ on the shortest side, you can run the entire chart through the printer without any preparation. If the shortest side is wider than 36˝, here are the steps to prepare your chart for printing on a large-format printer:

1. Separate your chart into strips no wider than 36˝ by gently separating the double-taped edges. If you used 18˝- or 15˝-wide freezer paper, you can run 2 taped lengths through the printer. (2 lengths of 18˝-wide freezer paper that has been overlapped by ½˝ with double-stick tape measures 35˝ in width—perfect to run through the bed of the printer.)

2. Cut ½˝ strips of regular paper and lay them over the exposed double-stick tape to eliminate its stickiness.

3. Roll up your freezer paper and take to the copy store or reprographic center.

If you haven’t used a large format printer before, you’ll be happy to know they have developed them to be as easy to use as regular self-serve printers. Most now require you to use a credit card to get started.

When you’re identifying your print settings, be sure to always select the black-and-white option. Color copies are expensive.

Once you’ve printed out your copies, roll them up and head back home. At home, realign the sections of your freezer paper and secure them together with brand new double-stick tape. Use double-stick tape to secure the sections of your new paper copy. Hang it up on your design wall or close to your sewing table for easy reference.

Project: Make a Copy of the Freezer-Paper Chart

You can either fold your freezer-paper chart in half to fit onto your home printer or print at your local copy or reprographic shop.

Cut Apart the Freezer-Paper Chart and Sort the Pieces by Color Codes

You have successfully completed all your charting and are ready to start cutting! You are probably feeling a bit more relaxed knowing that you’re headed back into your comfort zone where you can use beloved tools like rotary cutters, rulers, and eventually your trusty sewing machine. This is always a joyful transition point for me, too.

1. Manage your environment by closing any open windows and turning off any ceiling fans. Any source of a breeze across your table must be eliminated. You won’t believe how easy it is for these little facets to disappear into cracks and crevices!

2. Gather business-size envelopes. The number of envelopes should be equal to the number of facet/sections or the number of different colors in your color key, whichever is greater. Write the color code on the upper left corner of the front of the envelope, as well as on the upper left edge of the back flap. (This makes it easy to spot the correct envelopes regardless of whether they are laying faceup or facedown.)

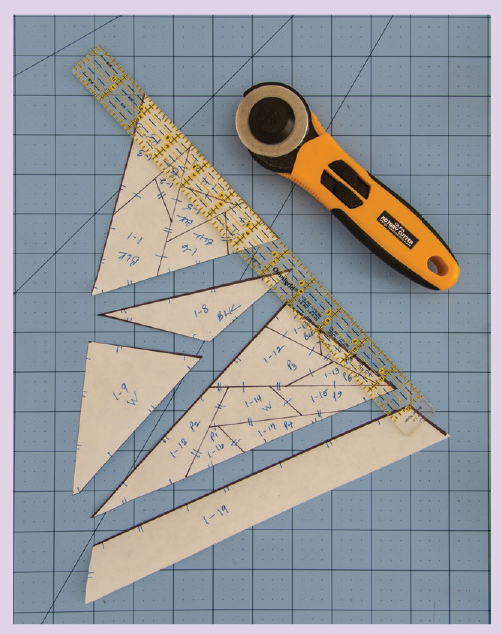

3. With a rotary cutter, ruler, and mat, slice apart your chart along the major facet lines. Working one facet/section at a time, slice up the pieces along your seamlines. While it’s okay if you don’t cut exactly on the line you’ve scribed, it is important that your cut be straight and not curved or wavy. That’s why I use a rotary cutter and a nonslip ruler rather than hand scissors to cut apart my freezer paper.

If you have Y-seams in your design, be mindful of not cutting too far beyond the point at which the Y-seams intersect.

4. Once you’ve finished cutting up a facet/section, take a moment to separate the pieces into piles by color code. Then insert the piles into their respective color-coded envelopes. It’s okay to fold freezer-paper pieces in order to fit them into the envelope.

Project: Cut Apart the Freezer-Paper Chart and Sort the Pieces by Color Codes

Working one section at a time, cut up your freezer-paper chart and sort into piles by color. Insert pieces in each pile into their respective envelopes.

Cut freezer-paper chart with rotary cutter and ruler.

Sort pieces by color code.