DATING CHURCHES

With such a wonderful variety of English churches it can be somewhat bewildering when first approaching one, when there will be so much that is unique to the building. This book can give you a basic grounding but if you wish to better understand a particular church then applying this knowledge is best done in a systematic fashion. Work from the whole to the part, look at the surroundings, the churchyard and the main structure before studying its detail.

Location

If the church is in the centre of the village or oldest part of a town, then it could be an early foundation. If it is remote but next to a large house or farm, then it too could be ancient, it’s just that the village has moved away. The building next to it is worth noting; a highly decorative church is often found to have had a bishop or abbot as a neighbour.

Churchyard

A roughly circular plan to a churchyard is an indication of an ancient foundation, although not a conclusive one, as is the presence of old barrows and standing stones. The build-up of soil from digging graves over the centuries can create a step up from surrounding areas and a retaining wall around the building, a sign again of an old church. Note the age of memorials; the church might be Victorian but older gravestones can tell you that there was another church before it on the site.

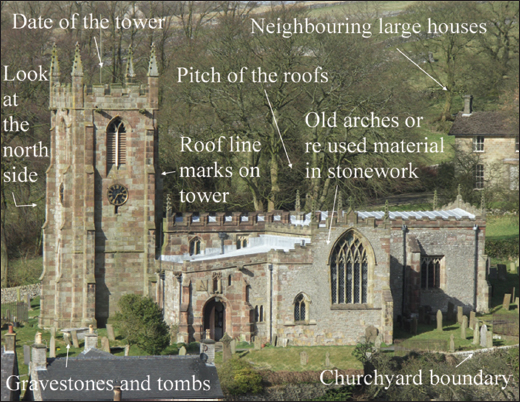

FIG 10.1: Some of the features, in addition to the style of the details, to look for when studying a church.

Structure

Note the arrangement of the parts and their general proportions. Tall, narrow naves and chancels are a sign of Saxon or Norman work although they are usually hidden behind later aisles and chapels. Central towers were popular up to the 13th century, west ones became dominant in the 14th and 15th. Original roofs were steep pitched and thatched, but were often replaced by lower pitched ones, leaving a mark on the east side of the tower (and sometimes the chancel remains at the original pitch as well).

Walk all around the church; never ignore the shaded north side as this is often where the best clues are to the age of the church. Note blocked doors and windows, the shape of the arch indicating its date. Faint arches in the stonework can indicate old aisles which have been blocked as the congregation reduced. Look at the stonework; if it is patchy and of differing quality then it will probably be old, if the whole building looks to be of the same with a neat plinth all around then it is most likely Georgian or Victorian. If the stonework is fine-cut ashlar then it is a sign of great wealth. If it is brick then it will usually be 15th-century at the earliest; thin, irregular bricks laid with no clear pattern date from this period, but have a definite bonding by the 17th century and are of regular size by the 18th.

Details inside can be just as important as those outside. The chancel arch and aisle arcades will often be older than the exterior would lead you to believe. The shapes of windows, style of decoration and the fittings within can help, but remember that most of these parts could be moved from other sites, like a monastery after the Dissolution or a neighbouring church when it closed due to falling numbers.

Name

The dedication in memory of a popular saint or event can be of note. Saxon names can indicate an early foundation while St Paul and Holy Trinity were popular Victorian names. The most common medieval church names were St Mary, All Saints, St Peter, St Michael, St Andrew and St John the Baptist.

Taking it further

Should you wish to find out more about a specific building then more detailed information should be available. Here are some suggestions:

* Booklet for sale inside the church.

* The Buildings of England series, initially by Nikolaus Pevsner. Each county is separately covered with details on the churches of every town and village at the beginning of each entry.

* The Victoria County History is a series of county-based books in which historians do all the hard work of translating and listing historic documents relating to a manor. Not every county is covered yet but if it has been completed then the library will hold a copy.

* Internet: Most churches have a site, although using a search engine can usually reveal more. Family History sites can be useful, especially about memorials.

* Listings: Most buildings will be listed and libraries often hold the study by local architectural historians when the listing was made.

* Records of the original builder like an abbey, bishop or lord of the manor will have information if available, and those responsible for the church today may also have details.

* Local history groups may hold information. In many abandoned churches archaeological digs may have taken place revealing a detailed history of its development. The reports should be available through the local library.

* Memorials or old graveslabs could indicate an early date. Look for some broken pieces built into later walls.

FIG 10.2 WHARRAM PERCY, YORKS: This deserted medieval village still has the remains of its medieval parish church (top left) which, as the area has been intensively studied over the past 50 years, has a detailed building history making it worth a visit to see how churches developed and declined. Details include the filled-in arcade (top right), reused graveslabs (bottom left), and rubble core of walls (bottom right).