Kamikaze Console:

Saturn and the Fall of Sega

PART TWO OF TWO

(August 1996 - March 1998)

The beginning of the end

As the memory of E3 1996 faded, Sega found itself unfit to do battle with either Sony or Nintendo. Several new Saturn titles were suffering production delays. Sega was losing money hand over fist due to Sony's bold move in forcing down next-gen console prices, so much that now Sega could never hope to break even on Saturn production costs. Rumors surfaced that Sega was going to drop the Saturn in 1997. Industry insiders pointed to Sega's steadily shrinking profits, shallow pockets, cranky console, and the lack of software. Sony was widely predicted to win the third great console war hands down. Sega's Japanese masters saw things differently, of course; N64 sales in Japan had all but ceased due to a dearth of software, and Saturn was still outselling PlayStation. What was happening in Europe didn't really matter; the market was too small to worry about. The situation in the United States was a mere aberration, and would be quickly corrected now that Kalinske was gone. The Americans would

come around...in time.

The confidence Sega of Japan demonstrated did not jibe, however, with the company’s performance in the one market that mattered most. Sega had somehow managed to sell over 500,000 Saturns in the U.S., but that was less than half the number of PlayStations sold. In gamers’ eyes, the PlayStation was cheaper and had more cool games, and this was reflected in the market performance. Sony was giving them more of what they wanted, while Sega had seemingly shunned its glorious past and was now alienating as many gamers as it could through high prices, lack of good software, and broken promises. Sony's share of the video game industry was growing by leaps and bounds as the 1996 holiday shopping season approached; Sega's continued to

plummet. The Saturn’s chances of surviving the third great console war were now slim to none. There was no longer a question of whether or not Sega could pull off an upset. Instead, everybody – except Sega – was wondering just how far the former champ would fall. They would find out soon enough.

Sega Saturn with type-2 controller

A bevy of quality Saturn releases – long-overdue in the US – arrived in the latter half of 1996: All-new NetLink versions of Daytona USA

and Sega Rally

, an Olympic sporting sim called Decathlete

, Kenji Eno's Enemy Zero

, fighting games Dark Savior

and Fighting Vipers

, and plenty of RPGs, including Legend of Oasis, Albert Odyssey, Shining the Holy Ark

, and Shining Wisdom

. Finally, Saturn had a decent chance of competing. From the start, the biggest issue with the Saturn had been a dearth of good software. Finally, it had arrived – and more was on the way. Now if only Sega hadn’t been so selective about what titles it brought over from Japan! The more the merrier, reasoned Sega fans and supporters – especially when it came to RPGs. GameArts was already porting its phenomenal Lunar

series from Sega CD to the Saturn, with another epic in the works called Grandia

. Early previews of the game looked as awesome as the name implied; with Working Designs working on bringing both of the Saturn Lunar

ports to America (and another reported to be planned), the chances of seeing Grandia

stateside seemed high. RPG-inclined American Saturn fans started saving their money, hoping for the best.

For those gamers not inclined towards RPGs, though, there was one big gap in Sega's expanding software base: There was no quality American football game on the Saturn. Saturn lacked the likes of Sega Sports NFL 96

or EA's Madden NFL 97

, and Acclaim's NFL Quarterback Club

franchise was widely known to be long on looks and short on gameplay – the Saturn incarnation included. As to how this could have been allowed to happen, it’s easy to blame Sega yet again – but the actual answer is a little more complex. At the time that Sega of America would have needed its in-house

programming teams to commence work on a football game for 1996, they were tied up – and would be for some time. Nearly everyone with any programming skill was hard at work on Sonic X-Treme

, which was running into all kinds of development roadblocks. Sega would happily have contracted an outside programming house to do the game, but none of the good ones were available – they were all busy developing games for PlayStation. There was one – a little start-up by the name of Visual Concepts – but they had just blown their first big shot by badly flubbing Madden NFL 96

the year before, causing EA to miss out on the PlayStation launch. Madden NFL 96

, which was to have been the first all-3D incarnation of the game, was cancelled, and Sony's own NFL GameDay

took its place. Now, in 1996, EA's teams were working overtime to bring a 3D Madden NFL

football game to the more profitable of the two 32-bit console licenses, leaving no time for a Saturn port. All in all, a rather unwieldy set of circumstances that came together to ensure that there would be no good football game on the Saturn in the fall of 1996. Sega’s dreadful oversight became clear once the American football season kicked off, and software sales figures started rolling in. NFL GameDay 97

was be the #1 football game of the year almost by default, with EA's Madden NFL 97

a close second. As for the Saturn port of NFL Quarterback Club '97

, it was nowhere to be seen on the charts.

Grandia

On a more positive note, Yuji Naka's NiGHTS: Into Dreams

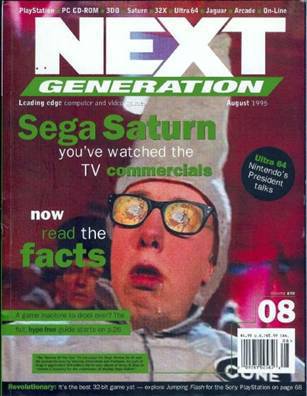

hit U.S. store shelves on August 21, 1996, bundled with a special "3D controller" and backed by an $8.5 million promotional and merchandising campaign – nearly as much as Sega had spent promoting the entire Genesis launch back in 1989. Sega was taking no chances, and even briefly resurrected the signature "Sega

Scream" in order to promote the game. Those who recall that campaign will also remember the "Full Freakin' Frame Footage" TV spots by Ingalls Moranville Advertising, designed to highlight as many of the game's features within 30 seconds as possible. "NiGHTS

is the most significant game launched for the Sega Saturn to date," said Sega of America president Shoichiro Irimajiri, "It proves the power of our multiprocessor architecture and demonstrates the fresh new direction in game development Sega is taking, like those in NiGHTS

and the rest of our fall lineup." NiGHTS

-mania ran high, with Next-Gen magazine speculating – correctly – that the game would be one of the best-selling titles of the season.

Saturn 3D controller

According to industry reporter Steven Kent, NiGHTS

- more than any other game - typifies both the good and the bad of the Saturn. Its atmosphere and design were exceptional; but while the game had a free-flowing 3D feel, most of it actually took place within two dimensions. While Nintendo and Sony were true 3D game machines, Sega’s was a 2D console that could handle 3D objects – but wasn't optimized for 3D environments. Kent's comment calls to mind the Saturn's origins as a 2D console – a heritage it was never really able to shake. Even Yuji Naka, arguably the best of Sega's in-house programmers, could not create a Saturn platformer boasting the same kind of open-environment feel his peers were crafting for competitors’ consoles, and admitted as much.

“In my opinion we still haven’t used 100% of the console’s hardware. We believe it is possible to make something much better. NiGHTS is our first Saturn game and, thus, we couldn’t take full advantage of the system. We have studied a lot of possibilities that we could have used and we haven’t even tried them. Just the basic manual has three volumes [laughs]. This time we have limited our own abilities.”

- Yuji Naka

That it was a great game ultimately didn’t matter. As good as it was – and as well as it sold – NiGHTS

alone could not save the Saturn. It was a situation that would eerily repeat itself roughly four years later, during the twilight years of Sega's last video game console.

By the end of August, Sega of America's financial situation was so dire that president Bernie Stolar discontinued all television advertising, effective the following month. It was a move Sega could ill afford – after all, television ads had been the backbone of Sega's earlier promotional efforts – but the company simply couldn't fund the sort of multi-million dollar, multimedia blowout for which it had been known. Stolar was berated by industry pundits and hardcore gamers alike, but he neither regretted nor apologized for his decision, and – in all fairness – Stolar's move probably didn't hurt Sega as much as suggested. By this time, it was clear who was dominating the American console markets – and it wasn't Sega. Stolar deemed it unnecessary to waste precious company resources on a battle he knew he couldn't win – instead, he was already looking beyond the Saturn.

It was around this time that the few American gamers who hadn’t yet committed to 32-bit consoles played their hand, and the choice was clear: The PlayStation was cheaper, had more games, and besides, got all of the really cool titles first – if not exclusively. Sega was no longer cool – old school, in fact – but the PlayStation was, and even Nintendo’s N64 was looking pretty promising. Sony's marketing machine had done its job, and done it well. PlayStation was the "in" system, with an installed user base of some two million consoles and growing. Saturn, on the other hand, was definitely "out," with just under 900,000 consoles sold and nearly no good games to be had.

Nintendo launched its N64 in the U.S. on September 29, 1996. All of the 350,000 allocated consoles sold out within four days, thanks largely to massive interest in just one game. Nintendo's mascot was making the comeback of a lifetime in his new 3D adventure, Shigeru Miyamoto's Super Mario 64

. Also of interest was a Star Wars

exclusive, Shadows of the Empire

, running in full-blown, light-sourced, texture-mapped 3D. That, in a nutshell, sums up the N64 software situation at launch. Just as in Japan, there was a dreadful lack of games – especially quality ones – and Nintendo's decision to stick with cartridges left new N64 owners shelling out as much as $80 per game. It didn't matter; American gamers had deep wallets, and there was still lingering loyalty to both the Nintendo brand and the idea of unbreakable

cartridges over easily damaged CD-ROMs. The release of Star Fox 64

and the impressive first-person shooter GoldenEye

(based on the James Bond movie) in the following months helped drive sales even higher. And while N64 sales didn’t come close to the PlayStation’s, Nintendo's arrival on the next-gen scene effectively eliminated any chance Sega had of making a Saturn comeback. Sega's already dwindling market share was cut in half by Nintendo's resurgence, and it was only a matter of weeks before N64 sales surpassed the beleaguered Saturn’s.

Why couldn't the N64 catch up with PlayStation? Those gamers watching MTV that fall know the answer, recalling a wildly popular TV commercial featuring a guy dressed up in a big orange animal suit standing outside of Nintendo’s American headquarters. Shouting at the building through a bullhorn, he challenges "Plumber Boy" to come out for a showdown. Nintendo's response? Security guards haul off the heckler at the end of the ad. This was the very first commercial for Sony's new 3D platformer, Crash Bandicoot.

Sony's Kaz Hirai, now running the American end of the PlayStation business, had wasted no time in tearing a page from Sega's own book, mating a quirky corporate mascot with bad-ass advertising. And it worked – "a rebellious image sells," after all. Gamers were seeing in Sony and Crash what they saw in Sega and Sonic only a few years before. Sales of Crash Bandicoot

were phenomenal, and Sony’s console sales figures rose alongside them.

Nintendo 64

PlayStation and its software’s sales skyrocketed, and N64 console sales continued to soar, while the Saturn was sinking, sparking speculation that Sega was seriously considering leaving the console business altogether. The rumors grew so persistent that Sega of America's Ted Hoff was instructed by his masters to address them. When questioned as to whether or not Saturn

would be Sega's last console, Hoff replied that it would not – Sega was committed to the console business. This came as welcome news to fans and industry analysts alike, who agreed that the sooner Sega jettisoned the weight around its neck, the better off it would be. Somewhere, surely, Sega was designing a successor to the Saturn. Hoff’s statement was as tacit an admission as any that Sega understood that the Saturn had failed – bombed, in fact. Big-time. There was only one way for Sega to even begin recouping its investment in Saturn, and that was to absorb those losses with the successful launch of a brand new console. Unfortunately, hardware development takes time and money – commodities of which Sega was fast running out. The situation is aptly described in Steven Kent's The First Quarter

:

“Things were now closing in on Sega. The company that had once proved that the market was big enough for two competitors was now demonstrating that it wasn't big enough for three.”

By September, Sony had shipped over 2.3 million PlayStations in the U.S., and over eight million worldwide. By the end of the year, they were making roughly $12 million a day in console sales alone, having sold about one million PlayStations during the 1996 holiday shopping season. Sony now controlled 50% of the console market, making it the majority player on the field. PlayStation outsold Saturn by a more than two-to-one ratio; the difference in software sales was even more dramatic. Nintendo sold considerably more N64s – some 1.5 million during the same season – but the sales spike wouldn’t last. In comparison, Sega had only sold just over three million Saturns total worldwide since the system's debut in 1994. It was "Déjà vu all over again" for Sega executives; they simply couldn’t counter that much market muscle.

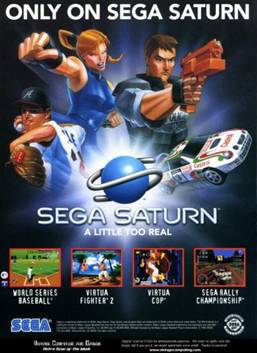

While mainstream market analysts in the U.S. confidently predicted the Saturn would miss its sales targets, Sega of America did its best to buck up the Saturn faithful, praying it might pick up some stragglers along the way. On November 18, 1996, it officially announced the first of its "Three-In-One" special software deals: Sega would include free copies of Daytona USA, Virtua Cop

, and Virtua Fighter 2

with every Saturn console sold. This calculated gamble worked so well that Sega of America renewed it through the end of the year and well into 1997. Saturn console sales saw a big holiday boost as a direct result of the "Three-In-One" promotion, with retailers reporting anywhere between a four and tenfold increase in Saturn hardware and software sales. Sega of America reported an approximate 175% increase in combined console and game sales. Sega of America sold another 500,000 consoles alone during the 1996 holiday shopping season – an impressive figure, to be sure – but still just half of its original holiday sales target of one million consoles. By the end of the year, Sega would report total worldwide

Saturn sales of just 3.6 million units. Sony’s PlayStation was still way out in front with 11 million units worldwide. In comparison, Nintendo and its N64 had caught and passed Sega in the U.S. market within mere months, and would do so in the worldwide market by the following year. Sega was far behind and falling fast, and it looked as if there was no conceivable way that it could catch up with its competition.

Sega Saturn flyer circa 1996

So how did 1996 turn out, once all was said and done? To put it plainly: The third great console war was now effectively over. Sony had triumphed, handily sweeping aside the opposition. In spite of this, Nintendo had successfully joined the next-gen wave with the N64, supplanting Sega as the weak number two on the console market, and leaving little room in which a third competitor could remain profitable for long. On March 31, 1997, Sega submitted its annual consolidated financial reports to its stockholders. Against all odds, it had managed to pull off a profit, but it was a paltry ¥5.57 billion ($46.4 million) – less than half of what the company had made the year before. Sega had not performed so poorly since the days before the Genesis came on the scene. As it turned out, 1996 would be the last year that once-mighty Sega would post a net profit as a console manufacturer. It almost appeared as if Nakayama and company were deliberately allowing Sega to devolve back into the industry whipping boy it had once been. And

the worst was yet to come.

Paying the piper

For Sega, 1997 was the year of reckoning. The once-proud giant, the third company to dominate the American video game market since its inception, now suffered its greatest humiliation since the "great crash" in 1983. The culture of corporate arrogance that had been leading it by the nose was now poised to bite it in the ass. All of Sega's mistakes from the past few years would come home to roost in dramatic fashion, ensuring that the Saturn would forever be considered a failure in the public eye. While its rivals were better financed and had stronger market positions, what happened to Sega in 1997 was nonetheless largely a disaster of its own making. It was during this year that Sega went from making clear profits per annum to posting massive losses, casting a shadow over the doomed Saturn’s future, and causing the rest of the industry to wonder if the company could ever rebuild itself again. All that led up to this point had set the stage; the time had come for Sega to pay the piper.

The first thing Sega did out of the gate was – true to form – to trumpet its console sales. 7.16 million Saturns had been sold worldwide as of January 14, 1997: 4.4 million in Japan, 1.7 million in the U.S., just under 900,000 in Europe, and 160,000 in "other markets." Even considering the beating that Sony had given them the previous holiday season, they were impressive numbers. At the same time, Sega of America renewed its Three-In-One promotion, but with a twist: from February 15 through April 15, Saturn gamers would enjoy a "buy two, get one free" deal on a dozen top Saturn releases. The free games initially offered were nothing to sneeze at: NiGHTS

, Sega Rally Championship

with Arcade Racer controller, Sega Worldwide Soccer,

and Virtual On

. The new promotion proved as popular as its predecessor, and Sega of America ended up extending it through the end of May. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Sega of America laid off about 100 personnel and rearranged its operations, battening down the hatches for what was anticipated to be another troubling year.

Sega kicked off 1997 barely maintaining the next-gen console lead in Japan, falling way behind in America, and practically irrelevant in Europe. Sega's lead at home was not to last, however, and it lacked the resources to stage any sort of serious comeback in the West. Anyone familiar with the market trends knew what was about to happen. Sony had started 1996 with an installed user base of 3.3 million PlayStations in the U.S., one-third of which had sold during the 1996 holiday shopping season alone. Sega, by contrast, had placed only 1.6 million Saturns in the U.S. homes. It too had moved about one-third of the total during the holidays, but the PlayStation had outsold the Saturn by more than two to one. Clearly, 1997 would be the year of the PlayStation. With Nintendo clinging on to a stronger-than-

expected second place, all that remained was to see just how far Sega would fall.

The rest of the video game industry was so sure of the PlayStation's impending dominance that they didn't mind Sony’s buying up exclusive rights to many of the best up-and-coming games for 1997 – a practice it had commenced the previous year once its success seemed assured. While Nintendo couldn't match this strategy, it had something Sony didn't: in-house programming teams fully capable of cranking many excellent games. Sega was fully capable of matching Nintendo's programming efforts; however, it lacked Nintendo's financial reserves, superior management practices, and canny marketing techniques. Despite being the best year the Saturn would ever have, 1997 was when Sega's reputation for failure as a next-gen console manufacture would begin to manifest. Wrongly or rightly, many industry pundits blamed the machine itself, its limited software base, and the clearly dreadful way that Sega was mismanaging the marketing of its flagship console. At times, it seemed as if Sega of America followed one brilliant marketing move with several bad ones. Few realized at the time who was pulling the strings, but already there were voices of dissent to be heard from within Sega itself.

In Mid-March of 1997, Bernie Stolar was promoted to the position of COO at Sega of America. Prior to this he had led Sega's third-party licensing; now, he was in charge of its entire American operations. Before joining Sega, he had worked with Steve Race over at Sony on the successful PlayStation launch. Stolar knew perhaps better than any other of Sega's American executives that the Saturn's days were numbered, and made no bones about it. "I felt Saturn was hurting the company more than helping it," he later recalled in an interview with MSNBC. "That was a battle that we weren't going to win." After fully assessing the situation, he went to his superiors in Japan and told them the truth: Sega of Japan needed to reevaluate the direction it was taking with its flagship console and, to use his own words, "...see how we can best manage the winding down of Saturn." To Stolar’s surprise, his audience was receptive – more so than he’d anticipated. It was as if Sega's Japanese executives had been milling about in their three-piece suits, knowing something needed to be done about Saturn but unsure of which way to go. "I don't believe there was direction before," Stolar later recalled. "It was a matter of, 'Let’s see the plan. Show me how it looks financially to our business plans. Show me how it looks towards where the company is heading and how it transcends into that.' And once I did that, they felt comfortable letting me do what I did." Stolar's success was due largely to the fact that he had a previously unavailable ally on Sega's board of directors – one who knew the business world well, and just how accurate Stolar's analysis actually was.

Bernie Stolar

That new dissenting voice within Sega corporate was Isao Okawa, a well-known and wealthy Japanese venture capitalist who joined Sega's board of

directors in 1997. Before this, he was better known as the founder and head of CRI (CSK Research Institute), as well as for his work with the Japanese government in building up Japan's high-tech business economy. CRI had been associated with Sega for many years, and Okawa had long been appalled at how poorly Nakayama and his fellow executives were running things. Although his new position within Sega was a largely ceremonial role, he was in effect the head of the corporation – making him both a voice and a force to be reckoned with. "The bottom line is that Sega was too loose with its money," Okawa recalled shortly before his death in 2001. "No matter what I told Nakayama, he just brushed me off, saying, 'Okawa-san, you do not know the gaming business.' What I do know is business. Nakayama may have known games, but he did not know business. As a result, Sega kept going after profit/loss and did not consider its balance sheets. They did not think about cash flow at all." Okawa further commented on Sega's mismanagement during this time:

“The business management of Sega left me totally dumbfounded. One of the basics of business is that you hand over the product to buyers and receive money in return. Unfortunately, our management personnel did not even seem to know this basic fact. That is why their attitude has been so nonchalant, even if Sega is accumulating debt. They have no concept of production schedules or product management on their minds. They think neither of balance sheets nor cash flow. They know a lot about games, but they do not know how to run the company.

”

Okawa's comments didn’t sound all that different from what Tom Kalinske, Paul Rioux, and Shinobu Toyoda had tried to tell Nakayama back in 1995, and chimed perfectly with what Stolar was now advocating from the West. It was the one point on which Okawa and Stolar agreed – their relationship was rather strained due to personality clashes – but it was enough. Sega had run the company into the ground with the Saturn. It was time to jettison the console and move on to something with a chance of turning a profit while there was still a Sega left to hawk it.

While the wheels of common sense were at last beginning to turn within Sega, the rest of the industry moved on. As the year rolled on – and the impending death of the Saturn became more and more evident – the rumor mill kicked into high gear. On March 12, 1997, a number of video game-oriented Internet sites reported that Sega had a successor to the Saturn in the works, known then by various names including Black Belt, Dural, Project Pluto, and Saturn 2. Soon after, rumors began to circulate of a 64-bit upgrade module for the Saturn – similar to 3DO's aborted M2 plug-in – that would also double as a RAM expansion cart. Ominously enough, the reported name for this rumored upgrade was Eclipse. To industry watchers and eager gamers, it seemed Sega was exploring two distinct possibilities for the immediate future: Either extending the life of the Saturn by a few years via hardware upgrade, or ditching it altogether for a completely new and more powerful system. Either way, Saturn's dim future and Sega's apparent indecisiveness on the matter left many a Sega gamer feeling confused and disheartened. But again, we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Before Okawa and Stolar’s policies concerning the Saturn's future began to bear on Sega's ailing fortunes, the remainder of 1997 had to play out.

On February 27, 1997, Sony dropped the price of the PlayStation to £200 in Great Britain and AU$200 in Australia; in North America the price was reduced to $100 just four days later. Three days later, Nintendo CEO Hiroshi Yamauchi announced that his company would meet Sony's price, which it did – dropping the price of the N64 to $150 approximately two weeks later. Ten days later, Sega announced that it was cutting the price of its top five Saturn titles by as much as 50%. On March 17, to accompany its price drop, Nintendo noted that it now had an installed U.S. user base of some two million consoles. Ten days after that, rumors began circulating among video game retailers that Sega was planning to drop the price of the Saturn to a mere $100. At about the same time, several leading video game magazines ran articles concerning a "special loss" that had appeared on Sega's consolidated earnings statement for fiscal year 1996. Sega was postponing its official annual statement until May (due to certain high-level corporate activity which we’ll get to shortly), but already word about the figures was leaking out, based on earlier Internet reports and confidential sources within Sega's own corporate structure. Sega would be taking a hit of $216 million "due to

problems with accumulated supplies of outdated game players (i.e. 16-bit consoles and software) and losses at its U.S. subsidiary."

The news shocked Sega stockholders and supporters as much as it did the rest of the video game industry. It was now obvious that Sega's PR department was going to blow a lot of smoke to cover the damage – if they could at all. Interestingly enough, that figure – $216 million – was the same as the net total of operating losses incurred by Sega of America over the Saturn to date, as reported at the end of 1996 by Sega managing director Shunichi Nakamaura. By April, Sony had sold 11.2 million PlayStations worldwide – five million in Japan, four million in the U.S., and 2.2 million in Europe. Sega’s announcement that it would meet Sony's price drop was another cut in revenue it simply couldn’t afford. It would now be selling Saturns at a dramatic loss, one which profits from software sales and additional revenues from other company divisions could no longer cover. Not that it mattered what Sega chose to do; Sony was already far in front, and increasing its lead by leaps and bounds.

Dragon Force

On April 25, 1997, Sega kept its promise concerning Saturn software and began cutting the price of some of its most popular Saturn titles, including such notables as Dragon Force

and Virtua Fighter 2

. On April 29, Funcoland became the first U.S. vendor to drop the price of the Saturn to $150 – over objections from Sega of America. Unsurprisingly, several other retailers promptly followed suit – they could see what was happening, and where it all was heading. On May 28, Sega revised its forecasts for worldwide Saturn sales, noting that it expected demand for the following year to drop to 1.9

million units – down significantly from the 4.16 million units it had already shipped. Also projected was a loss of some 46% in revenue from Saturn software sales. On June 3, Sega kept its second promise, officially dropping the price of the Saturn to $150. Not to be outdone, Sony had already arranged with many U.S. retailers to sell their stocks of older, less reliable versions of the PlayStation for a mere $130. By August, Sony's market share had effectively doubled, and it had unquestionably taken the lead from Sega in Japan.

Bandai logo

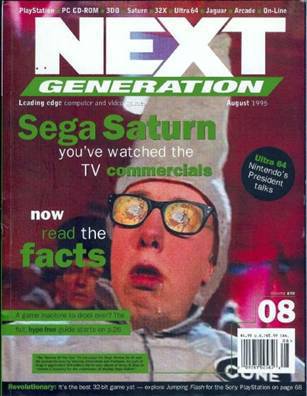

Sony now dominated the video game market in a fashion not seen since the late 1980s, when Nintendo had unleashed the NES on skeptical American audiences. On June 23, NextGen

reported that Sega had officially cancelled Eclipse, its planned 64-bit upgrade for Saturn, and with it went any hope among Saturn owners that their beloved console could be saved. Forced to face the unpleasant realization that their favorite gaming system would exit the stage within a matter of months, many simply refused to accept the facts for what they were. And as for the rest? It was now painfully obvious that the sand in Sega’s hourglass had run down: it was out of time, out of cash, and out of luck.

There was only one option left to Sega if it wanted to return to profitability and avert disaster: partner up or merge with another party – one with deep pockets. Not a competitor like Sony – that would have been a complete loss-of-face – but a friendly ally, or even an interested third party. No one knew Sega's withering financial situation better than Hayao Nakayama; after all, he bore more responsibility for causing it than anyone.

This mess was his fault, making it a matter of corporate honor for him to resolve it. Nakayama took it upon himself to save face by finding a workable solution to Sega's cash problems, ultimately settling upon merging with Japanese merchandising giant Bandai. He had broached the idea over dinner in 1996 with Bandai president Makoto Yamashina, who shared with his fellow executive the dream of a giant multimedia conglomerate to rival the likes of the Walt Disney Company over in the United States. It was a beautiful dream… But could they pull it off?

Founded in 1950, and having since grown to become Japan's largest toy manufacturer, Bandai is best known in the West for its merchandising of anime properties. This was an idea that Yamashina brought with him once he assumed the presidency from his aging father (and company founder) Naoharu, despite the elder Yamashina's objections. Makoto Yamashina's first such success was with the granddaddy of anime sci-fi mecha shows, Mobile Suit Gundam

. Toys based on the Gundam

franchise sold like gangbusters in Japan, so Yamashina continued with other so-called joint properties, expanding the concept to include such live-action television shows as Kamen Rider

and other youth-oriented fare. Like Sega, though, Bandai was now experiencing cash flow troubles due to the economic recession in Japan that had taken root in 1991. Its most recent joint properties – the anime television series Sailor Moon

and the most recent incarnation of its live-action Kyoryu Sentai Jyuranger

(aka Mighty Morphin' Power Rangers

) brand – were both past their prime and no longer raking in the profits. Additionally, Bandai's initial venture into the video game market – the Bandai Pippin – was an utter failure, and had to be ditched altogether. Nakayama and Yamashina, along with their respective staffs, had been in quiet negotiations throughout the latter half of 1996, working out the deal’s big picture, and leaving the finer details until after the planned merger’s date became definite.

On January 23, 1997, Sega and Bandai called a joint press conference and announced that Sega would acquire Bandai in a stock swap deal worth roughly ¥129 billion ($1.09 billion). "The idea," said Sega spokesperson Lee McEnany, "is to become the largest entertainment company from toys to theme parks to video games and music. We want to run the whole gamut. This merger will give us more leverage and power." Investors’ initial reaction was rather cool on the stock markets the following day, but they eventually gave grudging support to the idea. More news about the merger came four months later on May 24, after both companies released their long-delayed annual financial statements. Sega and Bandai planned to merge their company-wide operations by October 1, according to an agreement that was to be signed the following week. Sega's Isao Okawa would act as chairman of the combined corporation, Sega Bandai Ltd, with Nakayama serving as its CEO, and Yamashina third in line as company president. All that remained was the allocation of divisional tasks and the elimination of redundant

personnel. "It's an extremely complex merger, because you're talking about two global companies coming together," commented financial analyst Robert Burghart of IGN Barings Securities (Japan) Ltd. for a story by New Media News.

The merger agreement was to be signed on May 22. It never happened. It was the middle management of Bandai – many of whose jobs were about to be eliminated – who first raised a ruckus about the whole affair. They’d gotten wind of it in April, and the news apparently caused such contention among Bandai management’s ranks that the company board of directors postponed its initial decision to vote on the deal on May 1 by three weeks. It was hoped that the additional time would permit tempers to cool while more information about the merger was revealed, but the exact opposite occurred. Bandai employees were determined not to let Sega "absorb" their company (eliminating their jobs in the process), and vociferous objections continued to flare. Coupled with growing concern from rank-and-file employees, the incessant resistance of Bandai’s middle management gathered strength, growing to such proportions that it spiked the planned merger within days of its being executed. On May 26, Yamashina is reported to have contacted Nakayama, apologizing and saying, "I'm sorry, I couldn't persuade them." The next day, Bandai senior managing director Mikio Ishigami informed the press that his company was calling a special meeting of its managing directors in order to review the merger, resulting in its being delayed until mid-July. Over 80% of Bandai's middle management "had expressed concerns about changes in the company's culture and working conditions that would occur as a result of the merger," according to New Media News. Local Japanese newspapers were even blunter, reporting on growing numbers of Bandai employees dissatisfied with the encroaching merger. By the next day, it was all over.

On May 28, at separate press conferences, Nakayama and Yamashina acknowledged that the merger had fallen through, although the two would continue to work together along other lines. Both blamed "cultural differences" for the failure of the merger, albeit for different reasons. "It appears that among Bandai's younger-generation management class, the true purpose of the merger had not hit home and only the negative aspects were their focus," Nakayama said. He also commented that Bandai itself "would feel rather guilty" about calling off the deal. On the other hand, Yamashina "admitted that Bandai had run into trouble identifying exactly which synergies would have resulted from the tie-up, making it more difficult to persuade critics of the merger's value." On May 29, Yamashina announced his impending resignation; on June 26, at a special stockholder's meeting, he formally stepped down as Bandai president, retaining his largely ceremonial role as company chairman while denying that his actions had anything to do with the failed merger.

Mock Sega-Bandai logo

So what was the big deal? How were lower-level personnel at Bandai able to spike the merger? There were several smaller reasons that – when combined as a whole – predicated impending disaster to critics of Nakayama and Yamashina's plans. First was Sega itself: A company already on shaky financial ground and that stood to gain more from the merger with Bandai, with whom it had little in common. Second was their respective corporate cultures: Sega had a rather loose-knit, free-wheeling management style largely credited to its origins as an American entrepreneurial enterprise, while Bandai was a traditional Japanese company which operated along strict Japanese cultural lines. Third was Nakayama himself: He was not perceived as an ideal choice to run such a large company due the manner in which he was running Sega into the ground right before everybody's eyes. Fourth was a sudden turn of good fortune for Bandai: One of their new toy products – a virtual pet device called tamogatchi

– was proving to be a big success, and looked to generate sufficient revenue in the near future to make up what losses the company was currently incurring. Boiling it all down left many with a clear conclusion: Bandai didn't need Sega. Sega needed Bandai, who may have been the one posting a loss for fiscal year 1996, but had the merchandising strength to rebound. Sega didn't and never would. Bandai was always the deciding partner in the merger, and both Sega's and Nakayama's future success hinged on whether or not it went through. On May 28, 1997, as news about the failure of the merger was breaking, the following observation – shared by a number of financial market analysts – was posted on Dave's Sega Saturn Page

.

“In the long-term, Sega may have more to lose from the failed merger as it had become much harder to restructure its unprofitable game-machine operation without new blood and a boost in its earnings. They said Sega's video-game machine is losing money and is unlikely to turn profitable in the future.”

Nakayama was never able to bring Sega back into a position of market strength. The planned merger with Bandai had been his last throw of the dice. As 1997 rolled on, he quietly began making preparations to leave. On January 12, 1998, Nakayama tendered his resignation as chief operating officer of Sega of Japan. "Many speculate that the move by Nakayama is to take responsibility for the failed merger between Sega and Bandai, and the less than spectacular business achievements of Sega this past year," reported GameSpot News. The resignation became official the following month; Nakayama was booted upstairs to the newly created ceremonial office of corporate vice-chairman, and fellow executive Shoichiro Irimajiri was appointed by the stockholders as the new Sega CEO. By June, Nakayama had left Sega altogether. He was the last of Sega's founding management team to leave, and his departure ended a long and often dictatorial era in the company's storied history.

In the West, Bernie Stolar is the man most often blamed by Sega diehards for the death of the Saturn. Many reasons are cited, but they tend to boil down to three key issues: His feud with Victor Ireland of Working Designs over Sega booth space at E3 1997, his public statement at the very same show about the future of the Saturn, and his implementation of the Five Star Games Policy. Let’s take a moment to see just what bearing these items had on Sega's worsening fortunes in 1997. In truth, the Saturn was dying long before Stolar came onto the scene, but as he’s widely perceived as driving the final nails in its coffin, the argument bears closer inspection.

E3 1997 was held from June 19-21 at the World Congress Center in Atlanta, Georgia; the show had outgrown its previous stomping grounds in Los Angeles. The first keynote address was by IDSA president Douglas Lowenstein, who discussed the growth of multimedia and the rise of the Internet. Lowenstein noted in his speech that official NPD research data indicated that there had been a 58% increase in console game sales, some six million next-gen consoles were already in the homes of U.S. gamers, and that number was expected to grow to 16-18 million by the end of the year. The second keynote address was by NBC News anchor Tom Brokaw, on hand to discuss the founding of his employer's MSNBC online news service. What does all of this have to do with Bernie Stolar and the demise of the Saturn? Plenty, as it turns out.

Lunar Silver Star Story Complet

e

The first of Saturn’s problems at E3 1997 attributed to Stolar was the apparently spontaneous feud between Sega of America and software licensee Working Designs, its number one importer of RPGs. Due to a series of misunderstandings concerning scheduling and booth space (that still raise the ire of the principals involved), Working Designs did not receive the large area they were expecting within Sega's E3 booth. Instead, they were relegated to a small space in the back corner where hardly anybody could find them. Victor Ireland, president of Working Designs, had already developed a personal dislike for Stolar from the latter's days at Sony, where he exhibited brusque manners and dismissed "non-mainstream games" (i.e. RPGs) as being largely unprofitable. Ireland took the treatment his company received at E3 personally, perceiving it to be a direct insult levied by Stolar himself, and promptly announced that Working Designs would no longer support any Sega platform so long as Stolar remained in Sega's employ. Stolar may have been unperturbed, but Saturn RPG fans went berserk. While Working Designs was still committed to release the long-delayed RPG Magic Knight Rayearth

for Saturn, it had cancelled its work on the Saturn port of Lunar Silver Star Story Complete

, even though the game was reportedly nearing completion. Instead, it was bolting for Sony's camp as fast as it could, and would release the game for PlayStation instead. An upgraded and overhauled version of the highly-acclaimed RPG for Sega CD – including those parts of the game that had been dropped due to original development deadlines – Lunar SSSC

had been long and eagerly awaited by Saturn RPG players. Upon learning that the Saturn port had been cancelled, they took Ireland at his word, venting all of

their fury on Stolar over his reported behavior – even if a large part of it was undeserved. While it’s true that Stolar and Ireland weren’t exactly buddies (and never would be), it should be noted that Ireland had already decided that Saturn was a dead system, and was looking for a convenient excuse to take his company out of the Sega fold. The infamous incident of E3 ’97 gave him exactly the "cause" he needed to take his show elsewhere – away from a man he personally detested, and on to greener, presumably more profitable pastures. As for Stolar, he was reported to have privately expressed delight that Sega no longer had to deal with such a prima donna.

The second and more damning problem for Saturn was a single quote lifted from a speech Stolar gave on June 23, just two days after E3. "The Saturn is not our future," he said without hesitation during that speech, six words that would forever earn him the ire of hardcore Saturn fanatics. Stolar's quote was reprinted in a number of mainstream video game magazines, and plastered all over pro- and anti-Sega Internet sites in the months that followed. Rant after rant, rave after rave, flame after flame, the Sega faithful raged against Stolar and what he had said, and would do so for years. "For all practical purposes, Stolar buried the system alive while it still had a pulse left in it," noted one Sega site. Gamer Henry Knapp was even blunter, fuming "It seems as if Sega didn't want the Saturn to succeed." These are actually some of the milder comments one can find spurred on by Stolar's words, but he never apologized for his remark. Now focused on Sega's next console, he didn't really give a damn what happened to Saturn. It hadn’t and wouldn't make Sega any money…but its successor might, given the proper time and effort for a successful launch. A new console represented Sega's last chance at climbing out of the financial hole it had dug for itself. Above all else, Stolar had faith that the average Sega gamer would eventually understand… They just needed time.

Radiant Silvergun

The third of Stolar's perceived problems was his Five Star Games Policy, which went into effect on June 20, 1997. Often blamed for the dearth of quality Saturn titles in the West, it was, ironically, assembled in an effort to assure top-quality, top-selling Saturn games for the U.S. market. All submissions from both Sega's own programming divisions and its third party licensees were subject to the Five Star grading criteria, which emphasized "quality over quantity." If submissions did not receive a composite score of 90 or more, they had to be reworked or else they would be dropped from the release list. It sounded good enough when first announced at E3 in 1997, but soon came to be blamed by irate gamers as the reason why so many notable Japanese Saturn titles never made it out of Japan. Take Sakura Taisen

, for instance: This odd-yet-excellent combination of mech combat and romance simulation was wildly popular in Japan, and had a devoted following in the U.S., yet Sega never saw fit to release the game in the West. Saturn fans pointed to the Five Star Policy, which seemed to ensure that such a market-

specific title would never see the light of day in the West – and as the one who’d put that policy into place, Stolar was to blame. Other excellent titles were left behind in Japan, such as Radiant Silvergun

, considered the best shooter ever created for the platform and arguably the greatest arcade-style shooter ever made. A great many gamers from that day still blame Stolar’s Five Star Games Policy for the dearth of good Saturn titles in 1997 and 1998, while in truth the responsibility lies elsewhere. It was Sega's own executives over in Japan, not Stolar, calling the shots as to which Saturn titles would cross the pond. Stolar had more pressing concerns to worry about, such as ensuring that Sega’s Saturn left this world with some grace intact, while he readied its next system for its eventual market debut.

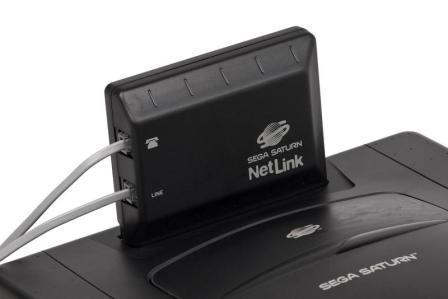

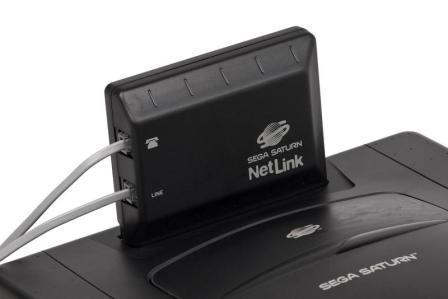

One of the Saturn’s often overlooked features in direct comparison with its competitors was its dedicated expansion port. Such a port could be used for various purposes: Sega's NetLink module, a dedicated MPEG playback card, or a RAM expansion cart. It was the RAM cart option that loomed large in the minds of Western Saturn owners in 1997; they knew full well that Eastern owners already had them and were enjoying games specifically coded to take advantage of them. Furthermore, Sega was letting third parties such as Capcom manufacture and sell their own Saturn RAM carts. Fighting games from Capcom and SNK boasted faster loading times, smoother animation, more colors and more intense action. It was even rumored that Capcom's in-development Saturn port of Resident Evil 2

represented such an overhaul of the PlayStation original that the RAM cart would be required. Rumor was all it ever was (and would be), yet the very notion of an enhanced RE2

port for

Saturn was enough to excite Sega fans at the time. RAM expansion capability was something sorely missed by Western gamers. PlayStation was a sealed box that offered no expansion options save those which could be somehow grafted onto the system's ports, and that did not include system RAM expansion. Only the N64 had a similar expansion port, but Nintendo's mindset on such devices was characteristically Nintendo: If it didn’t have their name on it, or was not manufactured at their facilities, it simply wouldn’t exist. In spite of all this (and the constant clamoring of North American Saturn owners), no official Saturn RAM cart was ever released in the West. Sega knew the Saturn was dying, and had been in negotiations for several months about licensing Capcom's own RAM cart and selling it in the West under the Sega label, along with Capcom's X-Men vs. Street Fighter

. Those negotiations fell through due to increasing concern over Saturn's plummeting market fortunes, however, causing Sega executives from both East and West to rethink their strategy. In their opinion, there was no point in releasing a costly piece of hardware to a market that was fast shrinking for one simple reason: there was no profit to be made. Hardware is expensive, and yields the lowest profit margin in a product line. Sega was already losing money on Saturn hardware, and, by every estimate they ran, would lose more by releasing the RAM cart in the West. No profit, no point. It was a simple business decision Sega executives were forced to make time and again during this period due to the Saturn’s diminishing market position – but it did little to assuage the growing ire of many a Saturn owner in the West.

Final Fantasy VII

On June 1, 1997, Square unleashed the mother of all RPGs on the U.S. market. Hironobu Sakaguchi’s love affair with the multimedia capabilities of the Sony PlayStation had finally borne fruit earlier that year in Japan, where his game had been an instant sellout. Final Fantasy VII

told a cyber-punk-infused story of a young warrior named Cloud and his rebel allies as they strove against the evil machinations of the Shinra Corporation. It had everything a next-generation RPG fan could want and more: Beautiful graphics and stunning cinematic sequences, a simple-yet-balanced game engine, and hours upon hours of gameplay. The staff of NextGen

magazine, no strangers to the genre, estimated that it took nearly 50 hours to play thorough the game from start to finish. It was a monster of an RPG, but more importantly, it was the genre's first next-gen effort. The 2D, super-deformed characters of the past had been replaced by 3D polygonal models. Static, overhead screen views gave way to dynamic camera angles. And full-motion video (FMV) was used to an extent that had not been seen since Lunar 2: Eternal Blue

on the Sega CD two years before. Final Fantasy VII

sold 2.5 million copies during its first three days on the Japanese market, making it the main reason why the Sony PlayStation finally surpassed the Sega Saturn in Japan. Japanese gamers were buying PlayStations for the sole purpose of playing Square's magnum opus, driving console sales at a rate with which

Saturn sales simply could not keep pace. Eventually, 90% of all PlayStation owners in Japan also owned a copy of Final Fantasy VII

. Recognizing a good thing when they saw it, Sony arranged with Square to have Final Fantasy VII

translated into English and released in the West.

Sega Saturn with Sega NetLink

Final Fantasy VII’

s North American market debut was even more phenomenal than in Japan, making it not only the console RPG of the year, but the biggest game of the year on any platform. To this day, it is considered a milestone in RPGs, and one of the hallmarks of the genre. The closest thing Sega had in its Saturn arsenal to combat the Final Fantasy VII

phenomena was GameArts’ Grandia

, another excellent RPG from the company that had introduced the Lunar

franchise to the genre. Grandia

, having done surprisingly well in Japan, had Western gamers loudly clamoring for its release, but the Ireland-Stolar feud ensured that the original plan for Working Designs to do the English port died a quick death. The only other way to bring Grandia

to Western shores would have been a joint in-house effort by both Sega and Game Arts, but both parties agreed that it would have cost more than it was worth. Western RPG fans’ opinions aside, it most likely would not have sold enough copies on the Saturn to turn a profit for either company. Ironically, it would not be until it was ported to Sony's PlayStation and then brought to Western shores that English-speaking RPG fans would finally get the chance to enjoy another excellent RPG from Game Arts. Why? Sony had the enormous, ready-to-spend base to make an English language port worthwhile. Sega and the Saturn did not, and never would

.

On June 19, 1997, Sega of America had five Saturn games on the market for its much-lauded 28.8 kbps NetLink modem, which enabled Saturn owners to surf the Internet with the included NetLink browser, and play NetLink-compatible games online. These games were Daytona USA CCE, Duke Nukem 3D, Saturn Bomberman, Sega Rally Championship

, and Virtual On

. But by July 3, 1997, plans had already scrapped been scrapped to release NetLink in Europe, with disappointing sales in the U.S. cited as the motivating factor. Given that there were some 15,000 NetLink users in the U.S. market – a dismal figure by any estimation – it’s no wonder Sega of Europe altered the deal. The NetLink fiasco marks one of a few instances where a poor decision by Sega decision wasn’t due to autocratic management, but rather the decision to tap a market that wasn't quite yet there. NetLink was way too early and far too expensive to be anything other than a novelty. Having the first Internet-capable console may have given Sega points for innovation, but it added nothing to its ever-eroding bottom line. Furthermore, many online-savvy gamers claimed that NetLink lacked the fun, challenge, and spontaneity of either the Sega Channel or Catapult's X-Band network, both of which were for the 16-bit console generation. NetLink had no sports games (such as Madden NFL

) and no fighting games (Capcom’s, for example); it was just plain “boring unless you were a Duke Nukem 3D

fan,” but that was about it as far as the action offerings went. Gamers looked at NetLink, thought, "That's neat, but it needs better games," and went right back to their Sony and Nintendo consoles. Like so many Sega products past, NetLink came too soon to do the company any good in the present

.

With the U.S. video game market primed for the final four months of the year – and the massive amounts of revenue to be generated therein – the writing was on the wall for the Saturn. Sony dominated the market with a 47% share for its PlayStation, boasting the most impressive software lineup of the year, with hit titles like Final Fantasy VII

raking in millions in profits. Not far behind was Nintendo at 40% – the largest share of the U.S. market it would achieve in the third round of the great console wars. As Nintendo of America vice president Peter Main had correctly predicted, the N64 was feeding off Saturn's corpse – even if it wasn't quite dead, yet. His numbers may have proven wrong, but his take on the initial trends had been right on the money. Having fallen to a 12% market share, Sega was still trending downward. Unable to match its competitors’ pace of rapid-fire price changes, Saturn's year-end software library paled in comparison. The few American Sega gamers that remained were, for the most part, bemoaning the lack of good software and bitterly complaining about Bernie Stolar’s recently instituted Five-Star Software policy. It wasn't really his fault – he was merely making the best of a bad situation – but Saturn gamers couldn’t see the big picture, and had no other outlet for venting their rage. As for the rest of the video game industry, they’d written Saturn off months before. Most of the mainstream industry magazines had already taken to calling it "a dying system," and several declared their eagerness to see the PlayStation ports of hot Saturn titles – like Grandia

– that never made it out of Japan. It was a reasonable request; Sony had a worldwide user base of 20.4 million PlayStations by September, and their numbers just kept growing.

Saturn wasn’t the only console headed down the proverbial drain; another of the 32-bit CD-ROM-based consoles was about to bow out altogether. On September 3, 1997, Panasonic formally withdrew from the U.S. video game market, taking with it 3DO – the console that started it all – along with the planned 64-bit M2 upgrade announced by parent company Matsushita less than a year before. Trip Hawkins’s dream of a single console standard among hardware manufacturers would have to wait. It was a vision that proved largely unworkable amid the proprietary-minded Japanese companies that dominated the scene, and another entire market cycle would pass before some of the seeds he’d sown with 3DO began to take root.

On September 30, 1997, Sega of America launched its last major advertising campaign in hopes of salvaging at least some of the holiday season for the beleaguered Saturn. Bernie Stolar managed to scrape together about $25 million for the effort, which touted the Saturn's prowess and the strength of its fall software lineup. There were the spot-on-accurate ports, of course: Last Bronx, Manx TT,

and Sega Touring Car Championship

. There were the Saturn-specific efforts: Enemy Zero, Fighters Megamix

and the highly touted Sonic R

, which Saturn gamers got in lieu of Sonic X-Treme

, but that sordid story will be told soon enough. There was the sports lineup: Madden 97

and Sega's

own NFL 97

. And then there were the third party efforts: Capcom's MegaMan X4, Resident Evil,

and Street Fighter Collection

, as well as id Software’s DOOM

and Quake

, and 3D Realms’ Duke Nukem 3D

, among others. Sega rightly boasted that Saturn was the only console on the market to have uncut, uncensored versions of the world's three best-known first-person shooters of the day. Stolar brought in a new advertising firm to manage the effort, knowing full well that Sega simply didn’t have the funds to match its competitors’ efforts. Not surprisingly, this last stab was a failure.

In retrospect, the Saturn’s last ad campaign is largely remembered for what didn't make it into the ad copy (but should have): Details about the games themselves. Most Saturn owners were offended by what they perceived as a big waste of time and money. The campaign failed to make any impression at all on the average gamer, at that time under a constant barrage of TV commercials and print ads touting Sony and Nintendo’s wares. Not one Saturn title – old, new or otherwise – entered the NPD TRST Top 25 Console Games list in either October or November, nor were any Saturn games to be seen on NextGen's

list of the top 20 console games of the year. To quote one industry observer, "A disturbing trend easily becomes apparent. The average Saturn owner has become a bargain hunter and an NFL junkie in need of a fix – any fix." When all was said and done, the Sega Saturn accounted for a mere 5% – at most – of combined holiday console sales, numbers that no right-minded corporate executive could ignore for long.

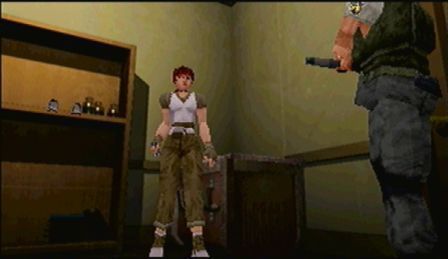

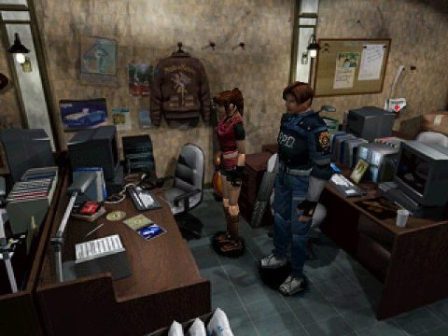

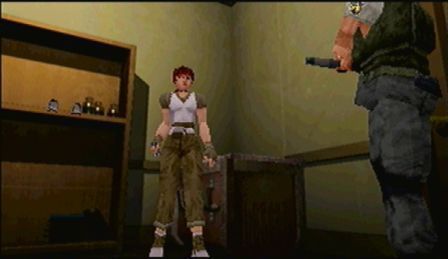

Resident Evil

On December 17, just as the 1997 holiday season entered its final mad week of shopping frenzy, NextGen

reported that Sega of America was planning "a substantial downsizing" after Christmas. An official spokesman for Sega denied the story, but nobody believed him. Rumors of all kinds were seeping through the cracks, and unofficial estimates of Sega's yearly profit-loss statement had the once-proud industry giant losing hundreds of millions of dollars. The official figures, announced at the end of the fiscal year on March 31, 1998, were damning: Sega had sustained a net loss of ¥43.3 billion ($360.8 million) in fiscal year 1997, and its own annual statement laid the blame squarely on the poor market performance of the Saturn. No one knew how such massive losses would affect the fate of Sega's next console, Katana, which had already been officially announced back on September 8. One thing was certain: Saturn was finished. It was now only a matter of when the axe would fall. As the saying goes, "If you can't run with the big dogs, then stay on the porch." Sega was barely capable of running at all, much less with its better-financed, better-resourced competition. Years of bad management and poor judgment found a major video game company – one which had enjoyed a reputation for innovation and creativity like few others – hoist by its own petard. Sega had violated one of its own major business axioms, failing to properly anticipate and adjust to a changing market. The company would

never be the same after 1997, the events of which would pretty much dictate the fate its next – and last – video game console, and Sega itself.

The case of the missing software

With all the negative things being said about Saturn, including by Sega itself, it’s no wonder that a lot of top-notch titles never made it out of Japan, or were never released at all. Although the Saturn’s last days would see the release of some of its finest games – Burning Rangers, Magic Knight Rayearth

and Panzer Dragoon Saga

, to name a few – there were just as many that Western fans felt should have hit store shelves, but didn't. Some of these omissions are blamed on Bernie Stolar, but the real reasons have nothing to do with his Five Star Games Policy. Here is a brief overview of some of the more notable Saturn titles that deserved greater recognition than they received, and some that never got out of the gates. It is the opinion of many Saturn fans and game historians that their presence was sorely missed in the West, where Saturn needed all the help it could get. Why weren’t they released? Let's have a look.

Eternal Champions: The Final Chapter:

This is arguably the most acclaimed 2D fighting game created by somebody other than Capcom or SNK, conceived of by Deep Water, one of Sega of America's own in-house programming teams. The Genesis version was pretty good, and the Sega CD version was spectacular, but both suffered from their respective consoles’ limitations. Eternal Champions: The Final Chapter

planned to pick up

on one of the loose ends from the Sega CD game – the appearance of the Infernals – and would introduce new characters and an all-new tournament. Sega of America was already souping up the game engine, and making plans to release the third and final installment on Saturn when their superiors in Japan nixed the project. Needless to say, they much preferred Virtua Fighter

– a game that had come from their own programming stable – to be the definitive fighting game for the platform. Sega of Japan killed Eternal Champions

for Saturn before one line of alpha code ever ended up on a dev kit, which is a shame; the Sega CD version received many good reviews, and American gamers were looking forward to a spiffed-up Saturn version. Word leaked in October of 1996 that the game was to be axed, with Sega of America reluctantly confirming the news before the year was out. In retrospect, Eternal Champions: The Final Chapter

could have been one of those regional titles to help push console sales – had it been given the chance.

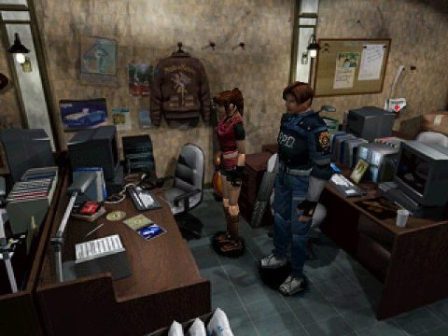

Grandia

Grandia:

In 1997, it was clear that Final Fantasy VII

was on its way to being a monster hit, and that there was one Saturn RPG Sega had in its Japanese arsenal best positioned to counter it. This was Grandia

by GameArts, released in Japan December of 1997, and already being hailed as both masterpiece and milestone in RPGs using 3D environments. To the surprise and anger of Western gamers, Sega passed on Grandia

, opting instead to translate and release the first installment of its own Shining Force III

series. For eager Saturn gamers and RPG fans following the video game market, this simply flew in the face of reason; but it was quite a different story in the

corporate boardrooms of the companies involved. What many Western gamers do not understand is that Grandia

for Saturn did not do all that well in Japan. It was a hell of a game – the best RPG created for the console, and an all-time genre classic – but it didn't exactly take the Japanese market by storm. On Saturn, the game only sold some 350,000 copies during its original market lifetime – good numbers for a Saturn game, to be sure, but nowhere near what Square's Final Fantasy VII

was doing. In the aftermath of the Ireland-Stolar feud, and facing the sad reality that Saturn had failed in the West, it’s understandable why Sega and GameArts agreed not to port the game. Their sales projections showed they wouldn’t make enough money off of an English language port in the West, where the Saturn market – already small – was shrinking daily, to justify the expense. On January 10, 1998, Sega angered RPG fans worldwide by announcing that Grandia

for Saturn would never be translated into English. It’s a grudge held by Sega diehards and RPG fans to this day, and made all the more painful by the English-language port Sony released for PlayStation two years later.

Blood Omen: Legacy of Kain

Blood Omen: Legacy of Kain:

This groundbreaking action RPG cast players in the role of Kain, a formidable warrior of old who returns from the dead as a powerful vampire in order to wreak havoc upon those who murdered him. One of the very first games specifically designed to take advantage of the CD-ROM format, it represented not only a milestone in video game construction, but a novel experience in its own right. It was

released for the PlayStation in August of 1996 to rave reviews, and shortly thereafter rumors began to arise of a Saturn version. This port, said to have been started shortly after the PlayStation version released, was to have addressed all of the earlier incarnation’s deficiencies, and more. The Saturn's 2D legacy would have made its version the faster loading and playing of the two, and Saturn owners eagerly awaited its release. In fact, a Saturn port was known to have been in development as of January of 1997 – with rumors running rampant that it would be released that fall – but Eidos quietly scrapped it long before it got near playable form. The reason? The Saturn was dying before everybody's eyes, and Eidos’ corporate heads felt they couldn't recoup the investment. Sad, yes, but that's business.

Resident Evil 2

Resident Evil 2:

The follow-up to Capcom's 1996 groundbreaking blockbuster "survival horror" hit, Shinji Mikami's Resident Evil 2

moved its monstrous escapades from the country hills to the middle of downtown. This time around, RPD rookie police officer Leon Kennedy and female biker Ezla Walker were forced to team up in order to survive a city overrun with zombies and other horrific creatures, with the resourceful personnel of RPD STARS nowhere to be found. Work on the PlayStation original was about 80% complete – with an official Capcom announcement already promising an eventual Saturn port – when Mikami personally ordered it cancelled, and the game completely overhauled. He was unhappy with how Resident Evil 2

was developing, and felt that it looked and played too much like the first game. In addition, the character of Ezla Walker wasn’t slotting well into the story, and some of the game's new features (including armor and clothing that would degrade throughout the game, and a new 'zapping system' in which actions taken and events experienced by one player character affected another) were proving difficult to implement. The team rebuilt the game’s plot and engine from the ground up, although a fair amount of the work they’d done earlier eventually wound up in the new version. As for the Saturn port – announced by Bernie Stolar on January 10, 1997, and by Capcom via one of its Capcom Friendly Club releases – it was scrapped for two simple reasons: There weren’t enough resources to work on it, due to the PlayStation original’s undergoing a major overhaul, and the impending death of the Saturn made the port appear unprofitable. RE2

’s overhaul was going to take a significant amount of time, delaying its release by at least a year. As the PlayStation version was to be released first, and work on it was already at the playable beta stage, there simply wasn’t time (given previously announced release dates) to even consider working on a Saturn port, regardless of profitability. Capcom felt that by the time a Saturn port would have been complete – 1998, at the earliest – the Saturn would most likely be dead; it simply couldn’t justify the additional work. There apparently never was a playable Saturn port of RE2

in any form, even in its earlier RE1.5

incarnation.

Rumors persist of an unplayable, 10% RE1.5

alpha build for Saturn, but I’ve been unable to confirm them and tend nowadays to disregard them. What information I have managed to dig up on the aborted Saturn port – and this comes directly from the developers themselves – indicates that it was to have been a straightforward port of the PlayStation original, with no enhancements or extra features requiring a RAM expansion cart. Had it been carried out, it would have required no more of the Saturn hardware than did the PlayStation original. Even as a straightforward port, it would have made a great addition to the Saturn’s library. But alas, it wasn’t meant to be.

Sakura Taisen (Sakura Wars):

The one Saturn game anime addicts dearly wanted Sega to bring to the West was one of the Saturn games least likely to ever make it out of Japan. Sakura Taisen

, (aka Sakura Wars

) combined action-packed mech combat with a delightfully entertaining dating simulation...and therein lay the problem. Dating simulations are quite popular in Japan, but have almost always bombed in the West. It didn't matter that the game had achieved the prestigious title of Overall Game of the Year in Japan, there was simply no way Sega would release such a game in a market without a sufficiently sizeable audience. To be frightfully honest – and I know this will irritate a lot of Sakura Taisen

fans – few gamers lamented the loss, or that of its later Dreamcast incarnations

.

Sonic X-Treme:

“The reason why there wasn't a Sonic game on Saturn was really because we were concentrating on NiGHTS. We were also working on Sonic Adventure – that was originally intended to be out on Saturn, but because Sega as a company was bringing out a new piece of hardware – the Dreamcast – we resorted to switching it over to the Dreamcast, which was the newest hardware at the time. So that's why there wasn't a Sonic game on Saturn. With regards to X-Treme, I'm not really sure on the exact details of why it was cut short, but from looking at how it was going, it wasn't looking very good from my perspective. So I felt relief when I heard it was cancelled.”

- Yuji Naka (2011)

Sonic X-Treme

Without a doubt, Sonic X-Treme

is the saddest "lost software" story in the Saturn’s saga. The game changed platforms five times, starting on the Genesis, but eventually moving onto (and through) the 32X, Sega CD, and Saturn before ending up as a PC game. You see, despite stories to the contrary, Sega planned all along to have a brand-new Sonic

game made for Saturn that would showcase the console's power, just as the original Sonic

had done for the Genesis years before. Although originally planned for the 32X, Sonic X-Treme

was to have been that game. Its loss is due to both its development team and to none other than Sega of Japan. As with subsequent Sonic

efforts, Sega Technical Institute (STI) in America was tasked with crafting the latest incarnation of Sega's beloved mascot. This time, they had a

formidable task – creating the first-ever, fully 3D, next-generation Sonic

game – but they had plenty of ideas, and wasted no time in throwing together executable code in order to demonstrate them. Sonic X-Treme

, as was revealed to video game industry reporters at the time, looked nothing short of fantastic. It had the look of every Sonic

lover's dream – full 3D environments enabling Sonic to maneuver in all directions, rich gameplay environments true to the series’ legacy, and more – leaving gamers worldwide salivating as 1997 loomed on the horizon. Early screenshots of the game, with its fisheye lens camera, looked promising… And this is where Sega of Japan enters the picture. The STI development team, headed by Chris Coffin, had been using the engine code from Sonic Team’s NiGHTS

, something Yuji Naka wasn’t too pleased about.

When STI was told that it would need to stop using the engine, development was set back by weeks – a delay the team could ill afford. STI also encountered major problems coding different parts of the game, leading to the development of two separate engines. When the engines – each in different levels of completion – were demoed to the brass from Japan, Hayao Nakayama chose to close out the one made for boss battles, effectively cutting the game in half. The situation was so bad that Sega of America was pulling programming resources from other departments (such as Sega Sports) in a last-ditch effort to overcome these obstacles, all under the code name of 'Project Condor.' Even this, unfortunately, was not enough to save the game, and stress began to bring down several teams with illnesses. Never recovering from this debacle, STI was disbanded shortly thereafter.

Elements of Sonic X-Treme

would wind up in Sonic R

, Sonic Jam

, Sonic 3D Blast

, and Sonic Adventure

for Dreamcast a few years later. On December 8, 1997, Sega of America released Sonic R

for Saturn as a sort of consolation prize to a disappointed American gaming public. Although it received wide acclaim for its stunning graphics, it was not the 3D Sonic game originally promised. Overall, opinions about Sonic R

remain mixed even today, with many Sega diehards declaring it to be no "true Sonic

game," and deriding it at every opportunity. The Sonic X-Treme

project was later revived as a PC-only “remix” version under Coffin’s lead, but was never brought to completion, and some of the design ideas were later seen in Sonic: The Lost World

for Wii U, fueling rumors that the game concept had been reborn, but no official announcement was ever made. It was only years later, when old in-house promo videos and some early alpha builds were rediscovered and made public, that Sonic

fans finally got a good look at this legendary long-lost game.

Virtua Fighter 3:

The third incarnation of Yu Suzuki's groundbreaking 3D fighting game hit Japanese arcades on September 10, 1996, immediately becoming the standard by which all comers were measured. Gameplay was incredibly deep, and the graphics (generated by the new Sega Model 3 board)

shattered previous records for polygon counts in a video game. Sega displayed some cabinets at that year's Electronics Consumer Trade Show in the U.S., leaving vendors and gamers alike wowed by what they saw. Naturally, VF3

soon became the topic of much speculation among Saturn owners. A port was inevitable – it just had to be – and rumors were already flying that one was well underway. Sega kept mum as the hype continued to build through the rest of the year and into 1997. Interviewed on November 28, Yu Suzuki said "AM2 and myself will take full responsibility for the translation." It was now official: VF3

was coming soon to a Saturn near you. Or was it? The port was delayed...and delayed...and delayed...until it dropped off the radar altogether. Sega of Japan had already begun hinting that the port might be canned in early 1997; its absence from the Saturn software section at E3 1997 seemed only to confirm this. Sega of America did plenty of back-pedaling on these and other reports, but then again, at this point they weren’t running the show.

Virtua Fighter 3 (Saturn)

Although widely unknown until the following year, Yu Suzuki and his staff at AM2 had finished a considerably scaled-down Saturn port of VF3

by July 3, 1998, but by then Sega of Japan was dead set against releasing it. Why? As was later revealed, Sega of Japan executives felt that a port of VF3

for the dying Saturn might hinder the superior port already in development for Sega's newest console – the Dreamcast. Instead, they just continued to tweak the game, while refusing to release it. VF3

for Saturn was officially cancelled

on September 17, 1998 – even though Sega of Japan had the completed game ready to send to press. Gamers – tired of Sega putting them on hold yet again – opted for the PlayStation and Tekken 3

instead.

Shenmue (Saturn)

Shenmue:

Originally listed as Virtua Fighter RPG, Shenmue

was one of the most expensive games of all time; the series’ production costs exceeded $70 million. Developed for the Saturn starting in 1996, Shenmue

was in development for the better part of two years before being canned, with development moved over to the Dreamcast. While little about the game was revealed during the Saturn’s lifetime, Shenmue

was apparently originally intended to serve alongside Virtua Fighter 3

as one of the console's swan songs. Use of the Saturn SDK 2.0 in its development made the game a showcase for both gameplay and graphics, proof positive that Saturn was still more than capable of standing toe-to-toe with the PlayStation and N64. While the game was eventually completed and released for Dreamcast, the Saturn version lives on as a “look at what could have been.” And although the original Saturn version still remains under wraps, snippets of what could have been can be spied amongst the extras included with Shenmue II

for the Dreamcast.

Last rites

With 1998 approaching, Sega Chairman Isao Okawa stepped out of his largely ceremonial role as leader of the company in order to salvage what