A Tale of Two Companies

Sega Europe

Preface

Tracing the history of gaming in Europe is a herculean task. Unlike the other two major markets, where a single marketing strategy informs an entire territory, such an approach in Europe is useless. Having dozens of countries and unique markets makes it difficult to document all that happened, especially in the 70s, 80s and in some parts of the 90s. While in other territories one can interview David Rosen or Tom Kalinske as to their motivations, in Europe there is always the question: who do we contact? In some cases, Sega’s main distributing companies didn’t even exist for at least 20 years, the key players are unknown, or sadly no longer among us. Although we are fortunate enough to have recovered information from some countries (such as the UK), in others, only snippets of the whole history remain.

The history of Sega in Europe is therefore assembled from an assortment of small bits of information discovered in old magazines, sales reports, and documented interviews, woven together in order to create an overall picture of what happened in the Old World.

A distinct market

By the mid-80s, Nintendo owned a sizable chunk of the Japanese and North American markets. Even Nintendo chairman Howard Lincoln recognized in later years that the first true competition the company faced came from the Master System. Nevertheless, Sega never presented a real threat to Nintendo’s NES dominance. In Japan, Rosen even admitted that two years of Nintendo had made the difference, while in the US the story was more or less the same. What, however, about Europe?

The European market of the 80s was quite different from the others. Rather than driving a console-driven market, Europeans generally preferred

computers as their primary system for games. The video game crash had taken its indirect toll, and the primary console market (U.S.) had stopped exporting to other territories. Although there were some European consoles at the beginning of the decade, none proved to be significantly popular. On top of that, breakthroughs in technology and production resulted in microcomputers could be easily produced en masse and at lower costs. Soon enough, the mass media was broadcasting news segments about how computers would change the world. Bit by bit, parents all across Europe, began buying computers for their kids – after all, people without access to computer technology would be left behind, went the thinking. And as it turned out, this wasn’t so far from the truth.

Soon market demand had grown so much that companies like Sinclair, Acron, Dragon, Commodore, Amstrad and Atari Corp found their footing. After all those computers ended up in consumers’ houses, however, their applications were few. What could you use it for, besides typing out text or using it like a fancy calculator? The answer presented itself soon enough: Games – not just playing them, but producing them. At the time, it was inexpensive to develop games and easy to distribute them, and by early 1983 there were over 300 game development companies in the UK alone, and growing.

Europe was a very particular market, indeed. Several countries occupying a small piece of territory meant that cultural, social, economic and political differences made marketing and distribution highly subjective. Not only did games and manuals need to be translated, not all titles were made available in every country or at the same price. When the first Japanese imports arrived in some European markets, it was soon discovered that simply putting consoles on shelves and running some reasonable marketing campaigns wouldn’t be sufficient. First a battle had to be waged for the hearts and souls of the home computer enthusiasts.

A different approach

When Sega and Nintendo first began to consider the European market, they took different approaches. Although Nintendo had already sold some Game & Watch electronic games in some territories (mainly Scandinavian countries, parts of France and neighboring countries) at the beginning of the 80s, distributing the Famicom/NES would have to be different. After negotiations in 1986, Nintendo signed a partnership with Mattel. The American toy giant became the official distributor in key European countries (essentially France, Italy and the UK). When the NES first appeared, however, no one was impressed. The price and overall quality of the console itself weren't especially attractive, nor were the terms extended to developers. Geoff Brown, President of US Gold, was one of those who doubted the console’s market appeal. In an interview given to Micro Hobby magazine (issue 185, February, 1989), he mentioned some of the system’s flaws, sharing an opinion that wasn’t so different from others’ in the development community; “Consoles will not succeed in the European market, they have three big problems. One, they cannot be pirated; two, the software is too expensive and three, the system is too weak. They are systems for bars, not for the home… We already have a Nintendo system in Europe, and it’s called [Sinclair’s] Spectrum.”

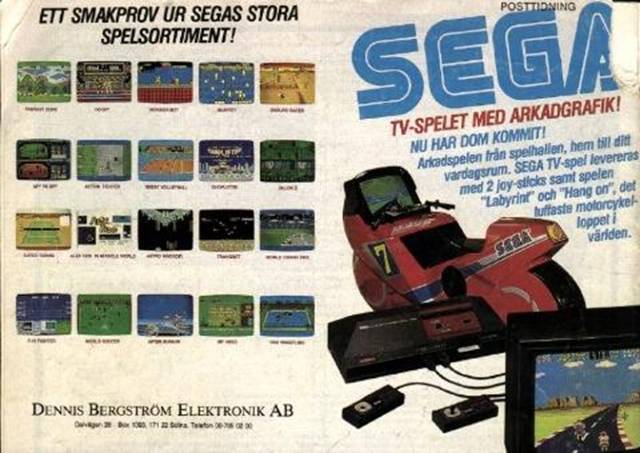

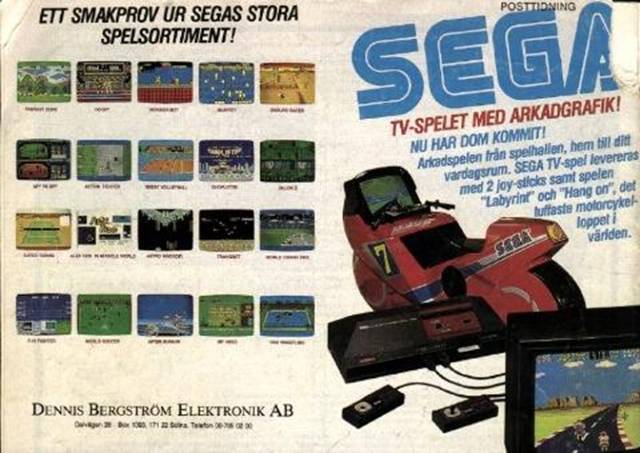

Scandinavian Master System advertisement

Overall, early NES distribution and reception in Europe was patchy, at best. Dissatisfied with the results, Nintendo revoked the license from Mattel

in 1989, and hired Luther de Gale as their European front man. However, the experienced ex-head of Konami UK later admitted to the press that – by the end of the decade – the home computer market was still stronger than consoles’, and that Nintendo had failed to win over consumers. Sega opted to take a different approach. At the North American CES of 1986, the company held a presentation for its new console. The main objective was to introduce the Sega Master System (SMS) into the US and Europe markets simultaneously. This meant that – unlike other territories – the SMS would be available in Europe at almost the same time as the NES. Several European companies returned home from the event with signed agreements to start distributing the system in their respective territories.

Spanish Master System advertisement

In West Germany, the first appointed distributor was Ariolasoft, a small software house with an existing distribution model. By the end of 1986, the company started their campaign for the SMS, and some German magazines had received the console and some of its games for the very first time. A little further to the south, in Italy, a small company called Melchioni had already distributed the Sega SC-3000 up until around 1985. By the end of 1987, however, the SMS was being distributed not by Melchioni, but by NBC Italia. One year later, Sega – unsatisfied with the weak results – revoked that license. The next year a company called Giochi Preziosi took on the job, utilizing more aggressive marketing campaigns than their predecessor, and even hiring Inter FC football/soccer goalkeeper Walter Zenga as their spokesman. By Christmas of 1989, the SMS was outselling the NES.

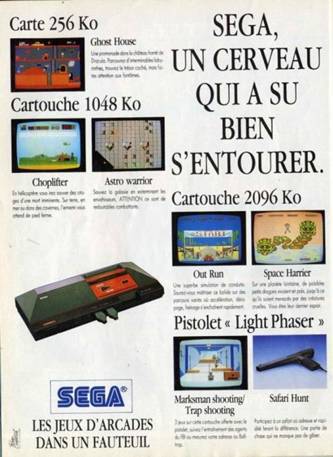

French Master System advertisement

Across the Iberian Peninsula,

Spain was another of the very first countries to receive the SMS. Although they got started after Germany and Italy, their distribution preceded that of France and the UK. By 1987, Proein was responsible for distributing the system, but lost the license shortly after, with Erbe Software taking over the following year. Like others, Erbe had started out as a small development studio; but as the industry progressed, they refocused on the distribution of software. Having the SMS license was a big win for the company, and soon enough their marketing muscle began to yield acceptable results. In France, a small company called ITMC released the SC-3000 to some parts of the territory until 1985. The following year, a different company – Master Games Systemé France – distributed the SMS without Sega of Japan’s official authorization. It’s believed that no more than a couple of hundred units were sold during this period.

In Northern Europe and in Scandinavian countries, several companies distributed the system. In Sweden, Dennis Bergström AB kicked off campaigns in 1987 before being replaced in 1990 by Brio AB. Throughout the first half of the 80s, Digital Systems distributed the Sega SC-3000 in Finland, although their numbers were largely irrelevant. Later, in 1987, Sanura Suomi began distributing the SMS and its games, with some Finnish magazines confirming that the company had attended CES 1986, and returned with an SMS license agreement. PCI-Data AB replaced them around 1990; however, they went bankrupt shortly after, and Brio AB returned to manage distribution in Finland the following year. Rather uniquely, in central Europe, a single company in 1987 held the license rights for three countries. Atoll was the official Sega distributor for Belgium, Netherlands and Luxemburg (aka

Benelux). Although these companies’ early efforts contributed to Sega invading Nintendo’s position in the continent, the most successful breach took place in the UK, all thanks to a company called Mastertronic.

Mastertronic

Mastertronic was founded in 1983 by Frank Herman, Alan Sharam and Martin Alper. Unlike many other companies in the UK, their main concern wasn’t developing games, but rather publishing them at competitive prices.

After a few years the company enjoyed a strong position in the marketplace, and in early 1987, Herman noticed that the console market – while big in other territories – didn’t have nearly the same impact in Europe. Studying the market, Herman soon discovered that while Nintendo already had a distributor in Europe (Mattel), their main competitor didn’t. Quickly, Mastertronic gathered a Sega official distribution license for one year.

Martin Corrall was appointed manager for the section responsible for Sega products, and his strategy was quite simple: keep the price of the SMS cheap (£99.95), so that the return cash flow would come from the games (£25 per title, on average). At the time, a NES was priced at £150, and games were £70. Home computer prices ran between £99 and £450, while games were on average £15 (full price), with budget re-releases to be found for as low as £1.99. Thus, Master System and its games offered the best average prices between Nintendo and home computers. Notable Master System cartridge titles included Fantasy Zone

and Choplifter

, while Hang-On

and Transbot

were the system’s Sega Card sellers. All of these games cost £19.95 per unit.

Unlike the NES – which was being distributed by a toy company – the SMS had the backing of a company that knew the video game market. In less than one year, all the materials sent by Sega to Mastertronic were sold out – including 30,000 consoles, and nearly 100,000 games – for a total of at least £5 million worth of stock. In 1988, Sega renewed their official license with Mastertronic, and also granted distribution rights in France, ending their arrangement with the struggling German company Ariolasoft as well. Soon after, Mastertronic was running the German and French territories, too.

From here on, the success of the console was proven to be solid, with peripherals like the Light Phaser gun and 3D glasses (used for playing games like Zaxxon 3D

) accompanying new games. The next step was to get software support from UK development houses. But there was one big challenge: The main console market had imploded in the US just a few years before, and European industry reps weren't convinced that the console market was a good thing.

In the autumn of 1987, The Game Machines

magazine rounded up a few developers and asked their opinion about the upcoming console market. Representatives from Telecomsoft, Gremlin, Ocean, Elite and US Gold

shared the same opinion: They didn’t believe in it. US Gold’s Geoff Brown even said, “it’s in the interest of the UK software industry not to support the consoles,” while David Ward of Ocean mentioned that “we do develop Nintendo software but only for the USA and Japan… I see them [consoles] as more of an alternative to a BMX than the home computers.”

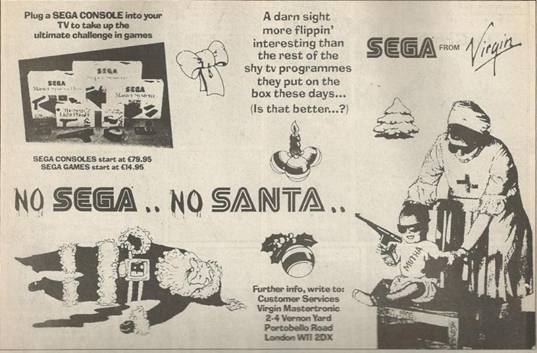

Nevertheless, in 1988, console sales were still stable – even without their support. In that same year, the Virgin Group purchased Mastertronic, renaming it to Virgin Mastertronic. Their main objective was to secure Sega franchising and become the main European distributor of the brand. One of their very first moves was to hand over distribution of Sega products in that territory to their French subsidiary, Virgin Loisirs.

“Virgin bought Mastertronic and wanted to have that as part of their portfolio, and because Frank Herman came with the Mastertronic name, they had good contacts with Sega, and Virgin Mastertronic became the vehicle for it”

- Andy Payne (CEO, Mastertronic)

By 1989, it was obvious that company’s budget computer games were largely irrelevant, and that Sega’s products were the future. Even home computers were starting to lose some ground to the consoles, spurring Virgin Mastertronic to try and to secure licenses for other countries. One of the very first of these was in Spain. After meetings in 1989, Virgin Mastertronic reached an agreement with Erbe Software to become the official Sega representative in Spain.

Virgin / Sega advertisemen

t

In 1991, Sega decided they were ready to take care of their own business, purchasing the Virgin Mastertronic division of the Virgin Group outright. Sega renamed the company Sega of Europe, but retained most of the team; Frank Herman was appointed Deputy Managing Director, and Alan Sharam named Managing Director of Sega UK. Later on, Nick Alexander would be appointed as CEO. Over in France, Virgin Loisirs became Sega France, while Sega’s arcade division was given to another company called Amiro. And with that, Sega turned its attention to the rest of Europe.

Although Sega was a powerhouse, it still lacked the capital to reach all of the Europe. Therefore, a special agreement was arranged: in countries where Sega still lacked official representatives, licenses would be handed out to companies that demonstrated an interest in its products. In Portugal, the license was given to Ecofilmes (1991), in Greece to Zegetron (1992), and in Sweden, to Brio AB – who were later appointed as official distributors to Norway, in 1995. Nearby, in Finland, PCI-Data had gone bankrupt in 1990, leaving PlayMix to take over the license. Soon enough, many of these distributors created the Sega official fan club with regional costumer support lines and exclusive perks for members, and released or sponsored officially branded magazines.

Meanwhile, a new version of the console was released in several countries. The Sega Master System II was a smaller, slicker, lower-priced version of the original console, dropping the Sega Cards slot, reset button and expansion port while adding a version of Alex Kidd in Miracle World

or Sonic the Hedgehog

stored in the ROM. While the US version was mostly grey, this edition was black.

In the following years, the SMS was considered in several countries as a low budget alternative to its 16-bit counterparts; by the mid-90s, it had gained a respectable customer base. According to Sega France (in Kahn, Alain; Richard, Oliver, “Les Chroniques de Player One

,” 2010, Pika), the Master System sold 450,000 units in 1991, and 304,000 the following year. By 1993, the numbers had decreased drastically, with only 83,000 units sold – presumably due to the growing popularity of the Mega Drive and Nintendo’s Game Boy. And in 1996, Sega finally retired the console in Europe – exactly one decade after its launch.

A European Master System

Unlike its performance in other territories, the Sega Master System became the overall number one third-generation console in Europe. And of course, no console can prevail without games. In the US and Japan support for the system had dropped off quickly, due largely to the exclusive contract agreements Nintendo forced its developers to sign. Sega was left with fewer options than ever to support their new console, with almost all of the SMS’s

games coming from Sega itself, or a handful of partners (such as Westone and its Wonder Boy

series). In the end, the total library for the Master System in Japan – and especially in the US – was extremely limited, with only about 100 games published in all.

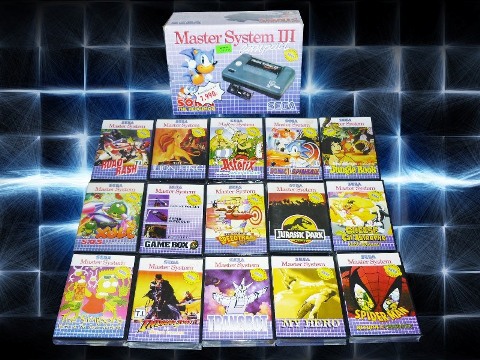

European Master System game set

In Europe, however, it was a different story. Although European developers had been slow to embrace the console market, that market had proven itself beyond a doubt by the early 90s. Soon enough, US Gold, Codemasters, Ocean, DoMark, Flying Edge, Infogrames and others began to consider consoles seriously.

“It’s possible that some of the companies that are currently working with Sega (circa 1992), will stop supporting the Master System. But, to balance that, we are going to get European developers, so that we can guarantee that the Master System will continue in the next years.”

- Nick Alexander (Sega of Europe)

Most of the early games for the Master System weren’t original efforts, but remakes of their respective developers’ hits for home computers, such as Kick Off, Zool

and Speedball

. Others were ports of popular arcade titles such as Paperboy, R-Type

and T2: The Arcade Game

. More than 100 games like these were released. As the years passed, the SMS also received unique adaptations initially developed for superior systems. TecMagik brought Populous

and Shadow of the Beast

to the system, while DoMark ported Formula 1

and Desert Strike: Return to the Gulf

. Sega contributed by releasing games that were based

on their 16-bit console hits, such as Shadow Dancer: The Secret of Shinobi, Streets of Rage

and Sonic the Hedgehog 2

. Naturally, there were also some games exclusive to Europe. Some of these include The Lucky Dime Caper Starring Donald Duck, Power Strike II,

and Master of Darkness

, as well as games bearing popular European characters such as Asterix and The Strumphs.

In the mid-90s, a curious bunch of games was released by Portugal’s official distributor, Ecofilmes, in an agreement with their Brazilian counterpart, Tec Toy. The two countries share a unique bond, so it was no surprise that the two official Sega representatives agreed on a collection of games, largely exclusive to Portugal. By 1995, 16 games were released for the Sega Master System, alongside a console called Master System III. All 16 are easy to spot, as the covers were mostly purple and in some cases bore box cover art different from the original (My Hero

is a good example). These games – known as the “Master System Portuguese Purple” releases – were almost all remakes of popular titles from other consoles, with one major exception. Based on a popular comic book character, Sapo Xulé: SOS Lagoa Proibida

was an exclusive game for South American audiences. The game itself was actually the Japanese title Astro Warrior

, with programmers changing the character and background sprites to fit the Brazilian character’s universe. In 1995, thanks to the agreement between Tec Toy and Ecofilmes, Sapo Xulé: SOS Lagoa Proibida

was also released in Europe.

Officially, support for Master System lasted until 1996, concluding with Les Schtroumpfs Autour du Monde

from French developer Infogrames. In the end, the official list of PAL games released for the SMS included a total of 269 games.

Populou

s

A firm foothold

In the early 90s, Sega had already established a decent presence in Europe. The Master System was generally outselling the NES, and the Sega name was gaining recognition among gaming aficionados. Their success wasn’t assured – home computers still proved to be tough competition. Commodore and Atari’s 16-bit computers were still big names in games in Europe, leaving consoles as an alternative. Electronic Arts’ 1991 fiscal report stated that 35% of their worldwide income profit came from Europe and its home computer market. In some territories (Switzerland, some Scandinavian countries and others) the SMS was lagging behind the NES. Generally, though, Sega was crushing the competition in the European console market – not only Nintendo, but also exclusive European consoles such as the Amstrad GX-4000 and Commodore GS64, which suffered due to mismanaged marketing efforts.

Virgin / Sega advertisement

Meanwhile, in Japan, 1988 saw the release Sega’s newest console, the Sega Mega Drive (MD), which launched in the US one-year later bearing the Sega Genesis name. In Europe, Sega was able to preserve the Mega Drive name. It was also reported that Sega was planning to release the system at almost the same time in Europe and US (repeating the strategy used with the SMS). However, production was delayed due to manufacturing issues, and the official release for Europe came only in the last months of 1990. At this time, Sega distribution in Europe still wasn’t entirely well organized. Virgin

Mastertronic was enjoying good results in UK – and decent ones in France and Germany – but the distributor partnerships with other countries were a bit of a mixed bag. All too often countries changed distributors, and only a few not controlled by Virgin Mastertronic achieved decent results (such was the case with Italy and Giochi Preziosi).

Sega advertisement

In 1990, Virgin Mastertronic attempted to grow its influence in Europe, negotiating with its Spanish counterpart to reclaim Erbe Software’s distribution license. During this period, Sega of Japan also decided to move more decisively in Europe, reclaiming from Virgin Mastertronic the official license. Negotiations began between the two companies soon enough, but it was only in 1991 that Sega officially opened Sega of Europe to oversee its entire European operation.

By then, Virgin Mastertronic had already officially announced the Sega Mega Drive in September of 1990, at the European Computer Trade Show (ECTS). Shortly after, the system was available in major department stores such as Rumbelow’s and Dixon’s, reaching France and Germany later in the year. The official price was £189.99, which included a console bundled with Altered Beast

. As with the other territories, initial launch titles were heavily focused on arcade ports, such as Ghouls ‘n Ghosts

and Golden Axe

. An exclusive pack for European audiences was made available later on, including Columns, Italia 90

and Super Hang-On

. The Mega Drive was no instant success. In March of 1991, Virgin Mastertronic reported having sold a mere 60,000 consoles in the UK, according to EIU’s 1991 Retail Business: Market Report. Similar to how things happened in the US, the system only really started to gain

momentum with the arrival of Sonic the Hedgehog

.

"Sonic was a phenomenon. It was iconic and, in my opinion, was the main reason for Sega's success against Nintendo in this period."

- Mike Brogan (Development Director, Sega of Europe)

In the same way that Nintendo’s Mario became a symbol for the gaming community in the US, in Europe those shoes were filled by Sonic (before that, most Europeans would likely select Dizzy from Dizzy Adventures

or Willy of Manic Miner

as being best representative of games in the 80s). Mimicking their counterparts, Sega of Europe made sure that Sonic’s popularity extended into several other strategic markets. All kind of merchandising bearing the hedgehog’s likeness started to appear: clothes, shoes, cookies, pens, dishes, books, kiddy rides… Sonic was everywhere, and on his way to becoming a phenomenon.

Sega’s market position was growing alongside its mascot’s. In the UK alone several publications sprang up over the years dedicated solely to Sega’s products, including Sega Visions, Sega Power, Mega Tech, Sega Force, Mean Machines Sega, Sega Magazine, Sega Pro, Mega Drive Advanced Gaming, Mega, Mega Action, Mega Power. Needless to say, Sega’s position in UK was very strong, indeed.

Sega España team

In Spain, after revoking Virgin Mastertronic’s license, Sega of Europe opened a new division called Sega España. Soon after, marketing campaigns for Sega’s system were seeing good results in the region, and the company’s popularity grew,

too.

Sega advertisement

“In (Spain) the handheld market without any doubt belongs to Nintendo and their Game Boy, but, in the home consoles, Sega and Mega Drive dominate the entire market.”

- Paco Pastor (Sega España)

Over the following years, Sega worked with its European partners to invest in events, TV shows and contests all across the continent, contributing to the overall awareness of consoles, and taking home computers’ place at the forefront of video games.

“My relationship with Sega of Europe was good, but with the Japanese it wasn’t so good. But at least during the Mega Drive period I did manage to convince them to create Mega Packs of the console. It was such a hit that we exported the concept to other markets.”

- Paco Pastor

In the meantime, Nintendo also opened European headquarters in order to supervise operations across the continent, choosing Germany as its base of operations. Backed by a strong marketing push, Nintendo managed to create a stronghold in Germany and France. In 1992, the Super Nintendo was released across Europe, but – as with the NES – the results didn’t reflect what was happening in the Japan and the US. The only foothold Nintendo really held in Europe overall was due to the popularity of its Game Boy handheld. Nevertheless, Sega France reported selling 162,000 Mega Drives in 1991; 475,000

units in 1992, 358,000 units in 1993, and in 1994 an impressive 995,000 consoles.

In 1993, Wired magazine reported that 66% of the video gaming market in Europe was dominated by Sega, with the UK, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece and some Scandinavian countries at the forefront. Nintendo’s numbers in these territories, on the other hand, ran between 10% and 30%.

Changing times

It was in 1992 that home computers really began to lose ground to consoles. Popular systems from Atari and Commodore had already been losing ground to IBM PC clones around the world; soon enough, their last stronghold in Europe crumbled, too. With the IBM PC as the new standard, and the downfall of microcomputers, consoles began to be seriously considered as an acceptable alternative for playing games. Development teams were also more receptive to publishing games on Sega’s systems. After all, the Mega Drive used the very popular Motorola 68000 microprocessor, which many developers were already familiar with (both the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga 500 used the same processor).

Global Gladiators

In no time, European studios such as Infogrames, Virgin Interactive and Sensible Software were porting older hit titles to both the Mega Drive and the Master System; some studios, such as Codemasters and Virgin Interactive were developing games for both at the same time. Micro Machines

and Global Gladiators

are good examples of this period.

Flashback

“Well, in a way, Mastertronic was partly responsible for the console boom – we made Sega a success in Europe and we were the company which became Sega Europe, the HQ of Sega's UK and European operations”

- Anthony Guter (Mastertronic)

As development studios’ concerns were assuaged, they started creating original games on the machine. The success of the Mega Drive was closely linked to these developers; Sega needed them, and also needed to start considering other markets. Having earned more maneuverability in Europe, Sega went searching for developers willing to sign exclusive contracts. One of the most famous of these was Hungarian developer Novotrade International, who created the environmentally-themed Ecco the Dolphin.

In France, Delphine Software employee Paul Cuisset commented on how gaming culture was changing. His game Flashback

(1992) was developed first for the Mega Drive, and only later ported to home computers – until then, most games came to computers first, and were only afterwards ported to consoles.

“The Mega Drive became our main platform. And yes, the Amiga version was the first to hit the shelves, but it was a port of the Mega Drive version. The main platform was the Mega Drive.”

- Paul Cuisset

Delphine Software even managed to convince Sega to produce cartridges with bigger ROM sizes. At the time, a Mega Drive cartridge would hold up to 16 mega-bits, but Flashback

needed more. So Delphine developed a 24 mega-bit cartridge and sold the project to Sega. Both parties won in the end, with Sega benefitting from new technology, and Delphine getting more space for Flashback

.

In the UK, Codemasters also developed specific cartridge hardware for Sega; its J-Cart (1994) was a special ROM cartridge with two additional gamepad ports, enabling up to four people to play. To prove their point, Codemasters developed a series of games – including three Micro Machines

titles, two Pete Sampras Tennis

games and Super Skidmarks

– to demonstrate the technology. Sega, meanwhile, had released a peripheral of its own, which enabled Master System games to be played on the Mega Drive. By helping seduce developers into creating games for Sega’s consoles, the Sega Master System Converter indirectly grew support for the system and its games.

“The Master System and Mega Drive were successful products and trailblazed the way for consoles, probably more so than Nintendo in the UK, and almost blueprinted the way that Sony came and did a really good job with PlayStation.”

- Andy Payne

By the mid-90s, Sega had in some parts of Europe become synonymous with “video games”. Elsewhere, however, Nintendo still enjoyed greater sales. Belgium newspaper Le Soir reported in September of 1993 video game console sales for the first half of the year: For Sega, Mega Drive sold 83,139 units, Master System had 318,310 units, and the Game Gear 39,616 units. Nintendo in the same period sold 50,131 units of its SNES, 178,616 of its NES, and 318,616 Game Boys. Atari’s Lynx trailed last, selling 20,227 units. The report concludes with a study conducted by GFK, in which video games

were voted as the most desired toy among kids.

In France, in 1995, a sales report prepared by Daniel Kaplan and Hervé Leduc (“La télématique française en marche vers les autoroutes de l'information”) mentioned that the console market was growing fast and overselling home computers; “this year our figures estimate that the console market represents a number closer to seven million; 2.3 million of NES, two million of Game Boy, 700,000 Master System, 300,000 Game Gear units, one million Mega Drive units and 100,00 shared results between Atari and Amstrad home computers or Neo Geo consoles.” One thing was for sure: Sega was indeed helping to change the games market in Europe.

Is that a TV in your hand?

Atari Lynx

By the end of the 80s, video games were enjoying phenomenal results all over the world. Over in the US, with the memory of Atari’s mistakes still lingering, many didn’t think the console market could last. In Japan, meanwhile, Nintendo prepared to release another breakthrough system. 1989 saw the launch of the Game Boy, followed shortly after by the Atari Lynx. Sega’s Game Gear released in Japan 1990, followed by concurrent launches in the US and Europe the following year, with Sega of Europe running the show. The system came bundled with Columns

, and launched at a price of £99. As the two units shared many of the same components, Game Gear was marketed to developers as a “portable Master System” – in other words, games could be easily ported from the console to the handheld. With Sega’s third generation console was still going strong in Europe, many development studios were seduced into supporting Sega’s new portable system.

By 1992, several titles were available for Game Gear; some were ports of arcades hits or popular home computer games, while others were prepared at the same time for all three of Sega’s systems. Sega also released two peripherals – the Sega TV Tuner and the Master Gear Converter – in hopes of helping drive sales. The intention with the former was to provide an affordable alternative to portable televisions, thereby broadening the system’s appeal. The latter made the Game Gear compatible with SMS cartridges, immediately expanding its library of games – a very important feature in Europe. Unlike other territories, support in Europe for the Master System was still strong; Sega could not only sell old stock, but also even sustain interest in SMS cartridges.

Game Gear advertisement

As for the competition, although the Lynx had launched in Europe, it posed no threat. The American handheld enjoyed an initially warm reception – due to lingering fondness for the Atari ST – but interest soon subsided, redirected at Sega and Nintendo’s portables. As in the US and Japan, the Game Gear’s biggest competition came in the form of the Game Boy. Nintendo’s handheld hit Europe in the early 90s, and its success mimicked

that of other territories. Once established, Nintendo of Europe enjoyed some autonomy from their Japanese counterparts, and devised a series of strategies for the entire continent. Their Trojan horse wouldn’t be the NES (that battle was pretty much over), but the Game Boy. In France alone, the first sales projections pointed to 500,000 Game Boys sold in 1991 (the handheld’s debut year). Instead, Nintendo went on to sell a staggering 1.4 million units, making the Game Boy the first console to oversell a Sega system in Europe, and even helping lift sales of the NES along the way. Nintendo hired local agencies to create their marketing campaigns, and special merchandising was developed for its offices all across Europe. By 1992, Europeans had snatched up six million Game Boys.

Sega of Europe soldiered on, and in 1996 the Game Gear’s last games were released. Having sold over three million hardware units, the handheld was discontinued in the same year as the Master System. Overall, the system enjoyed decent results in Europe, with an impressive library of almost 200 dedicated PAL games – factor in the SMS converter, and that number gets even higher. Although it didn’t enjoy the same level of success as the Mega Drive and Master System, Game Gear would be the stiffest competition the Game Boy ever faced.

The CD Revolution

Over the years, CD drive technology was quickly becoming more and more widespread; naturally, the video gaming industry took note. By the early 90

s, European home computer enthusiasts were becoming familiar with an assortment of systems using this new breakthrough, some exclusive to the territory. In 1991, Dutch company Philips released the CD-i, while Commodore launched its Commodore CD-TV, followed by the Commodore Amiga CD32, and the 3DO Company’s partners produced multiple versions of the 3DO. And, at the Tokyo Toy Show, Sega demonstrated its CD drive peripheral for the Mega Drive.

Philips CD-i 910

In early April of 1993, the Sega Mega CD was released in the UK. The unit cost £269.99, and came bundled with Sol-Feace/Cobra Command

and Sega Classics Arcade Collection

(in some other countries only one of these two titles was included). Mimicking the Mega Drive’s launch, the Sega Mega CD encountered several delays and manufacturing issues. By the end of the year, there were few units available in Europe; in some countries, such as Spain and Portugal, this first model didn’t ever arrive, at all. Sega of Japan later revealed that Europe had received 70,000 units, and practically sold out of all of them.

Surprisingly enough, a second, lower-priced version dubbed Sega Mega CD II arrived just a few months later, typically bundled with Road Avenger

. And again, both Spain and Portugal received this version months before the redesigned Mega Drive II. This was a major mishap; although the Mega CD II was also compatible with the original Mega Drive, it was specifically redesigned to fit the Mega Drive II. Compatibility with the original Mega Drive was a bit messy, as it needed extra parts to be added during assembly. According to some UK magazines, a small percentage of Mega Drive users actually picked up the peripheral. Most of the games weren’t very impressive, and many were simply ports of already available titles. Furthermore, the disasters of the Commodore and Philips systems had made Europeans wary of CD-based games.

European development support was quite modest, especially when compared with other Sega systems. Most European studios played it safe, focusing on porting titles instead of creating Mega CD-exclusive games. DoMark preferred to be on the publishing side, and teamed up with other companies to port games over to the system; their partnership with Bullfrog resulted in Mega CD versions of Theme Park

and Syndicate

. Psygnosis chose a similar strategy, and in 1993 and 1994 they published several games, including Shadow of the Beast II; Puggsy

and Microcosm

. With regards to European exclusives, Dephine Software offered up Heart of the Alien,

the official sequel to the popular Another World

.

Curiously enough, Sega helped Sony get into the gaming market, by introducing new studio Sony Imagesoft to European developers. Sega’s goal was to garner support for the Mega CD from a company that had contributed to the creation of CD technology. Some strategic partnerships in Europe resulted, with Sega publishing Sensible Soccer

in cooperation with Sensible Software.

“I know it sounds strange today, but Sony back in those days didn’t have a clue how to do video games. Not a clue… Olaf Olafsson was head of Sony Entertainment, they didn’t know how to do video games and so he asked us at Sega to help him. Since we needed [Mega CD] third-party support, of course we helped Sony. We lent them the people, the technology, we literally taught them to program video games.”

- Tom Kalinske (President, Sega of America)

Perhaps the most representative European company was Core Design, which developed nearly ten games for the system. Some were ports of popular games – including Chuck Rock II, Wolfchild, BC Racers

, and Jaguar XJ220

– while others, such as Wonderdog

and Battlecorps

, were system exclusives.

Without a doubt, the one game that had everyone talking about the Mega CD wasn’t European. As in the US, Night Trap

quickly turned heads – although not always for the right reasons. Whatever the cause, the furor helped raise awareness and drive sales of the system.

"Night Trap got Sega an awful lot of publicity. Questions were even raised in the UK Parliament about its suitability. This came at a time when Sega was capitalizing on its image as an edgy company with attitude, and this only served to reinforce that image."

- Mike Brogan

Heart of the Alien

By 1994, the Sega Mega CD was all but forgotten alongside so many other CD-based systems. The lack of attractive software and saturation of “interactive movies” had taken its toll, with very few games exploring the system’s potential. Less than two years after release – and despite Sega’s

having created games compatible between the Mega CD and their new Sega 32X peripheral –the system was still considered a novelty. Its final games were released the following year, mostly just out of contractual obligation.

“The Mega CD could have been a huge success… It was a “Home Entertainment Center”, besides playing its own video games, it could also be used for audio CDs… If the price was a little bit lower, together with a price reduction of the Mega Drive games, it could have become a success. I did manage to convince Nick Alexander (Sega of Europe), and he gave me authorization to travel to Japan, to explain this strategy to Nakayama. Unfortunately, my persuasion wasn’t good enough. “

- Paco Pastor

Billboard magazine reported in June of 1994 that worldwide sales of the Sega Mega CD had reached one million – a record at the time for CD-based consoles. Of those, Europe contributed only 170,000 units, with the UK at the forefront, followed by France. Demand in Germany was low, and at the Nuremberg Toy Fair of that year, Sega of Europe reported that sales of the (more expensive) Multi-Mega were far outstripping orders for the Mega-CD. The Mega CD proved Sega of Europe’s least supported system, with a library of less than 100 titles.

“They thought we were crazy…”

Following the Mega CD’s disappointing results, Sega continued to find ways to expand the Mega Drive’s life span. In the mid-nineties, fifth

generation consoles – including the Atari Jaguar, 3DO, and Amiga CD32 – were starting to appear, and Sega needed to start thinking about the future. In the meantime, they produced a new peripheral for the Mega Drive.

Surprisingly, the Sega 32X would be made available almost simultaneously in Japan, the US and Europe, where it launched as the Sega Mega Drive 32X, and priced at £169.99 (in the UK). The initial reception was superb, and weeks after its general release, some countries reported being out of stock. There was a demand for new titles, but there were too few options on the market, or even chances that they would ever exist.

"January 1994; Saturn was due to hit the streets within a year, development kits were scarce in Europe and still in the early phases, and support from Sega was very limited, so timescales for developers were ludicrously tight. Then suddenly we dropped 32X on them with even tighter timescales. They thought we were crazy – and we were!"

- Mike Brogan

Many of the developers that signed early contracts for 32X games either canceled them – planning to take those projects over to the Sega’s upcoming fifth generation console – or simply rushed them to market. By 1995, fewer than 50 games were available for the 32X, including two European exclusives: Fifa Soccer’ 96

and UK-based Frontier Developments’ DarXide

. The latter was one of a handful of games produced in Europe; other examples include Core Design’s Mega CD game BC Racers

– ported by US Gold – and Novotrade’s Kolibri

.

Kolibr

i

“Sega users might have switched camps after the experience of 32X or the Mega CD. Nobody gave us credit for at least trying to broaden the games market, they unfortunately came at a “boom-and-bust” period… For our sins, we didn’t support it as much as we should have done, and with that started a bit of distrust.”

- Andy Mee (Sega of Europe)

In a desperate bid to move more units, Sega of Europe offered £50 discount vouchers with every 32X, but it was too little, too late. By the end of 1995, the 32X was selling even less than the Mega CD, making it Sega’s worst-selling system in Europe.

Education for all

Another Sega system launched in Europe at about the same time as the Sega 32X. The Sega Pico was a very basic console aimed at young children between two and eight years old. In other words, a Trojan horse intended to put the Sega brand before young audiences. The console was released in all key European markets, earning acclaim from the European edutainment community, and even praised by some education professionals. Unfortunately, support from developers wasn’t so strong, and once again, most of the Pico’s titles came from Sega’s subsidiaries.

One of the key issues was language. Having the game support multiple languages was a big expense for companies. A Mega Drive title could have multiple languages built into the game’s ROM, but the Sega Pico used book-shaped cartridges with turnable pages – more like a toy – driving production costs up. Regardless, Sega’s subsidiary Novotrade created games for both Europe and North America, including Tails and the Music Maker, A Year at Pooh Corner

and Smart Alex and Smart Alice: Curious Kids

. The only confirmed European exclusive was Professor Pico and the Paintbox Puzzle

, released in 1995. In the end, fewer than 20 games were released before the system was discontinued in late 1997.

“Pirates” with an edgy attitude

By the early nineties, it was becoming clear that a bulk of the European market belonged to three countries. As much as 50% of Nintendo and Sega’s European operation profits came from France, Germany and the UK. Secondary markets included Italy, some Scandinavian countries and the Iberian Peninsula. Austria, Benelux, Denmark and Greece were considered the third. As is the case even today, Eastern European countries were not considered priorities. Naturally, it was during this period that Sega began to focus its efforts on the UK and France, followed by Italy, Spain and Portugal. Sega of Europe had grown rapidly, climaxing in 1993; naturally, such quick

growth came with consequences.

“After the Olympics in Barcelona, in the next year [1993] we had a critical period of restructuration that lasted 2 years. Not only in Spain, but also in the rest of Europe. The company was making adjustments and reducing the titles launch. One of the toughest periods I came across. ”

- Paco Pastor

"Sega Europe's development division grew from about eight people to approximately 80 in this period. It was an exciting time, but in retrospect we were too ambitious. Around half of those numbers were software engineers, graphic artists and musicians, because we tried to start an internal development team from scratch. That was a mistake. We should have relied more heavily on third party developers. Managing a staff of that size was a challenge."

- Mike Brogan

Many of Sega’s third market operations weren’t presenting compelling arguments as to their value, so it came as no surprise that Sega decided in 1996 to close down operations in Austria, Belgium, Denmark and Switzerland. The distribution of Sega products continued in these countries, with other companies – such as Koch Media – granted distribution licenses by Sega. With this strategy, Sega of Europe hoped to concentrate more of its efforts on the remaining markets, as they prepared to push future systems and games.

Marketing for video games in Europe had grown over these years, with Sega and its partners contributing to overall awareness of video games. At the end of the 70s, a few magazines about computer hardware started to appear, some even including sections devoted to video games. Over the next decade, magazines, TV shows and other forms of media dedicated to the industry began to appear throughout Europe.

Canal Pirata Sega

By the end of the 80s and into the 90s, Sega and Nintendo unveiled increasingly professional ad campaigns in Europe; but unlike what was happening in the US, negative ads were uncommon. Instead, many campaigns focused on celebrating the systems capabilities and games. As the early 90s continued, Sega of Europe and its partners took a different approach, opting for edgier, faster-paced commercials in the vein of the “Nintedon’t” campaigns in US. One notable example appeared in the UK: Sega Pirate Channel

was a fictional unlicensed TV network that interrupted ersatz commercials to talk about Sega’s latest games. A similar campaign appeared in Spain, dubbed Canal Pirata Sega

. Both campaigns featured a skull in the logo, which became an unofficial secondary mascot for Sega in Europe. Perhaps in paying a little homage to the European pirate community, Sega was helping create a more rebellious image.

Naturally, different slogans were used to pitch Sega products, depending on the country. The UK had “To be this good takes AGES! To be this good takes SEGA!” In France, it was “Sega c’est plus fort que toi” (“Sega is stronger than you”), which was mimicked by Portugal’s “Sega é mais forte que tu.” Spain also used a variation on this, “La ley del Más Furete” (“The law of the strongest”) and before that, “Uma nueva dimension en videojuegos” (“A new dimension in video games”). In some countries the old Master System slogan “Do me a favor… Plug me into a Sega” was also carried on into Mega Drive campaigns. And in some territories, advertisements and commercials from elsewhere in Europe or even the US were simply overdubbed and/or subtitled.

In the mid-nineties, Sega launched a revolutionary project to enable downloading through cable TV and onto the console. It was called Sega Channel. In Europe only a few countries carried the service: naturally, the UK was at the forefront of this campaign, which launched in 1996, courtesy of Flextech PLC for a £10 monthly fee. In Germany it was offered by the Deutsche Telekom at a cost of DM28 a month. Later on, it was offered in the Netherlands at a cost of DFl 20/month; and finally, in France, it was Multithematiques S.A. that broadcast the channel.

“Tele-Communications International has established successful partnerships around the world… We have plans to commence distribution arrangements in Western Europe immediately, with other ventures, like Flextech PLC in the U.K. and Multithematiques S.

A. in France… We look forward to working with them to bring Sega Channel into homes in overseas markets."

- Nick Fiore (VP and Managing Director International, Sega Channel)

In the roughly three years that the service was available, around 50 games were offered. Curiously, some of the games made available were NTSC, and based on North America ESRB rating system. The channel also announced upcoming game releases, showed trailers and broadcast some news related to Sega operations.

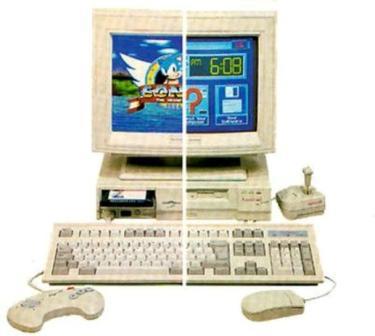

In an effort to diversify Sega’s product line and appeal to Europe’s computer enthusiasts, an agreement was signed between Sega of Europe and UK-based computer company Amstrad. In 1993, Amstrad released a hybrid system – half Mega Drive, half PC – onto the European market. The Amstrad Mega PC was essentially an IBM-compatible system, with a Mega Drive ISA card and some less-than-high-end components. Released at a price of £999, it included a white/beige Mega Drive controller, an Amstrad joystick, keyboard, mouse and monitor with internal speakers. Marketed as a business computer with “fun” capabilities, the reception was modest at best. The price was considered too high, and some components – such as the Intel 80386SX processor – were almost outdated at the time. It was cheaper to buy a more up-to-date IBM PC clone and standalone Mega Drive separately. Amstrad soon reduced the price to £599, and released a new version with an 80486 processor – the results proved no more popular than its predecessors. These systems show Sega of Europe’s insights as it tried to diversify its products, and its market

position was so strong that a computer company would be compelled to make such a hybrid.

In the end, all these campaigns made their mark. Sega sold nearly seven million Mega Drive units in Europe, alongside 543 PAL games, becoming Sega’s best-selling console in the territory.

Amstrad Mega PC

Sega World

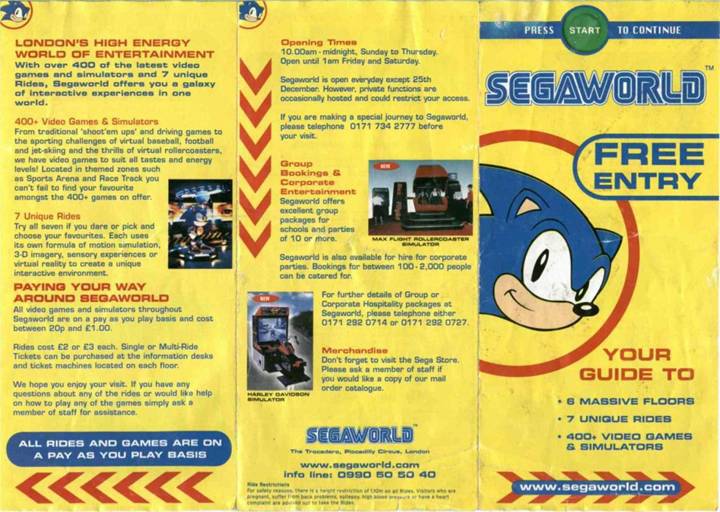

Without a doubt, 1993 was Sega of Europe’s best year yet. In order to build up the Sega brand, theme parks dedicated to Sega products were built in the UK.

"In Europe Sega has to work very hard in the consumer market. We will take this idea as far as it will go. It will have a synergy effect. We're providing the thrills and enjoyment people can't get at home."

- Yasuo Tazoe (Director, Sega's development division)

The first park opened in Bournemouth in July of 1993, dubbed Sega World, although later renamed to Sega Park. Unsurprisingly, the focus was on Sega’s arcade machines and memorabilia. In London, in September of 1996, Sega World London opened up in Piccadilly Trocadero with a big serving of Sonic.

Sega World brochur

e

"It will be a vehicle for Sega itself. Both consumer and coin-operated launches will take place here. The Sega Saturn and game peripherals will be also available in the on-site store.”

- Peter Searle (Development Director, Sega Amusements Europe Ltd.)

As The New York Times reported, “Sega World, which opened last weekend, occupies 110,000 square feet (10,200 square meters) on seven floors in the Trocadero entertainment center in Piccadilly Circus. It is said to be the largest indoor theme park in the world, dwarfing Sega's two existing theme parks in Japan. The company invested 8 billion yen ($73.1 million) in this European flagship operation.” It closed down at the end of the decade.

Reaching Saturn

By the mid-nineties, Nintendo’s biggest seller in Europe was the Game Boy, which – besides selling at an astonishing number – helped NES sales and later on, created awareness of the SNES. However, neither of these consoles proved as popular as their Sega counterparts. Nintendo even attempted to control the European market, creating price-fixing strategies, preventing high-priced exports originating from low-priced countries. In 2002, an investigation conducted by the EU concluded that during 1991-1998, “prices in the UK were cheaper by 65% when compared with the Germany and Netherlands markets…traders that allowed exports to occur were punished by being given smaller shipments or by boycott altogether.” Nintendo ended up paying a €168.843 million fine, the fifth-largest amount ever imposed for anti-trust infringement at the time.

With the exception of its Game Boy, Nintendo really didn’t pose much of a threat to Sega’s dominance. But another Japanese company was about to enter the market. By 1994, the Sony PlayStation was already out in Japan, and scheduled to hit Europe the next year. But – unlike Nintendo – Sony was backing it with a big budget marketing campaign.

The 3D paradigm

Up to this point, developers had been creating sprites in games for over ten years. In 1994, some 3D games made for consoles, such as Starwing

and Virtua Racing

, sold in respectful numbers. Innovative as they were, though, they didn’t send the game industry diving into this new trend. Even the Sega Saturn was being designed as a 2D machine. Regarding the widespread implementation of 3D, the gaming industry was divided. Today it seems only logical that CDs and 3D would be a perfect marriage. But in the first half of the nineties, the technology was expensive, the few 3D graphics cards that existed didn’t attract big audiences, and even DOOM

– an evangelist for the 3

D gaming experience – used sprites. Sony may have been planning a 3D-based console, but interest from the gaming community was low.

Tomb Raider

“When we did

Fade to Black we had to create a whole new engine, and we had a lot of technical problems because we were learning how to place the camera, how to control the character. It was really something that we had no experience of. It was a very interesting experience, but also a frustrating one.”

- Paul Cuisset

The game that changed it all was Sega’s Virtua Fighter

, which soon caused developers to acknowledge the benefits of 3D. One of the early European studios to succeed in 3D was UK-based Core Design, one of Sega’s more reliable allies. Core developed games for the Master System, Mega Drive, Mega CD, Game Gear and 32X, making Sega a lot of money, and boosting Sega’s market position. In the mid-90s, the studio began work on a new project that forever changed the industry. That game was Tomb Raider

.

“Sega had been very good to me. They had transformed my company and I had made a lot of money out of Sega. I felt I could give something back to Sega by giving them a three-month exclusive and hope it would help them with their sales… But, when Sony came out with all guns blasting, they ripped Sega apart. Everyone saw how great Tomb Raider was in the Saturn and was waiting for it to come on the PlayStation and when it did, its hardware sales went through the roof!”

- Heath Smith (Founder, Core Design

)

The timing couldn’t have been more perfect. With the “girl power” movement gaining memento in the UK, female audiences were pleased to finally have a strong heroine in video games (even if the character’s design still squarely targeted teenaged boys). Soon enough, Tomb Raider

became one of the early frontend titles for the fifth generation, and for a while, a system seller for Sega Saturn. The game’s leading lady, Lara Croft, became a strong symbol of what European game developers could bring to the industry.

Saturn rising

By 1995, Sega Saturn was unleashed into almost every territory in Europe. The early reception was as expected; the system was soon out of stock. Several marketing slogans were used. In the UK it was “Welcome to the real world” and “The game is never over.” On the Iberian Peninsula, it was “Dangerous real.” And in France the taglines “De-program-yourself” and “We are not on the same planet” were used. The Saturn was being publicized as something out of the normal world – a new dimension in gaming. During this period, Sony had been tapping into its big marketing budget, and had already managed to create some buzz over the PlayStation. The N64, on the other hand, was far away; other systems were either considered not to be a top priority for gamers (Neo Geo CD) or dismissed outright (3DO, Atari Jaguar).

Atari Jaguar

In the early days of the Saturn, perfect conversions of popular Sega games such as Daytona USA

, Virtua Cop

and Virtua Fighter

made ideal calling cards for anyone interested in the new console. European support also started to appear, but most of the titles were only scheduled to arrive in 1996, while others were rushed to market and with good reason soon forgotten

.

“One of the things we learned since the launch of the Saturn is that we’ve let some people down with the quality of our titles. Looking back to things like

Virtual Hydlide and

Mansion of Hidden Souls, there were a few titles that perhaps we wouldn’t have wanted.”

- Andy Mee

During the 1995 Christmas season, the Mega Drive continued to outsell the Sega Saturn. Unlike things over in Japan, the 16-bit console was still appreciated in Europe, and still enjoyed community and developer support - in fact, the Mega Drive wasn’t discontinued until 1998. So, for some time, the Mega Drive was the Saturn’s biggest competitor. Naturally, it didn’t last long.

Sega Power reported in their 1995 December issue that Sega of Europe was still planning to support every console that the company had on the market. In other words: The Master System, Game Gear, Sega Pico, Mega Drive and 32X would live alongside the Sega Saturn. This breadth of products would prove to be a huge financial burden on company’s entire European operation.

“Like many other manufactures do with their TV’s, we have different products at different prices in the market… This Christmas we will sell far more Mega Drive than Saturn, and this is likely to be the case for some time to come, as the Mega Drive is an integral part of our plans for the next couple of years.”

- Mark Maslowicz (Spokesman, Sega UK)

Although Nintendo had so far been a supporting actor in the European theater, Sony wasn’t about to play so nicely. A $2.4 billion worldwide marketing budget ensured that the new console’s name was broadcast almost everywhere; thanks to some promising titles, gamers started to take interest. Sony also moved in on developers formerly allied to Sega. In 1993 they purchased Psygnosis, in anticipation of the 1995 introduction of the PlayStation. Others European studios such as Codemasters, Infogrames and Virgin Interactive would also show some early support.

“I think we realize now that there will probably be a greater installed base of PlayStations. But as long as we’ve gone ahead and met our budgets and targets, which we have done – we said a million units by end of the financial year and we’re on target – we have a viable business to go forward.”

- Andy Mee

In 1996, Saturn was still selling in decent numbers, but losing ground to the PlayStation at an alarming rate. Furthermore, titles were starting to be canceled or postponed. By the middle of the year it was clear that Sega’s market position was collapsing, and the Saturn’s high price wasn’t helping.

The PlayStation was cheaper by about £100, and its games cost less, too. In the UK, the magazine market had started to shift towards PlayStation, and many Sega-centric magazines disappeared. Nevertheless, some soldiered on, some even giving away excellent perks. Sega Saturn Magazine

packed a Christmas NiGHTS

CD in its 1996 holiday issue; later they even offered the first complete disk of Panzer Dragoon Saga

(not to be confused with a demo).

By the next year, the stream of Sega Saturn games arriving in Europe was becoming smaller and smaller. Many of the games that hit big in Japan or the US would stay there, and multiplatform titles wouldn’t get ported to Saturn. Even Core Design, with its historical relationship with, Sega decided not to bring its Tomb Raider II

to Saturn. Nevertheless, a few notable 2D titles eased the burden. The most popular of these were fighting games such Street Fighter Alpha 2, Marvel Super Heroes

and X-Men Children of the Atom

. Together these games helped keep Saturn and Sega’s name afloat.

Christmas NiGHTS

At E3 in 1997, Sega officially spoke about its upcoming new generation console, which many developers took as code for “Sega Saturn will be discontinued shortly.” A lot of projects were canceled – some by Sega itself –while other developers lost trust in the company altogether, and decided to focus on the PlayStation instead. During the same year, Nintendo released the N64 in Europe. But by this time, it was too little, too late. The PlayStation’s two-year advance had given it dominance over the market, and it was digging a progressively bigger gap between its sales and the other systems’. Nintendo, in any case, focused on the next closest target – Sega Saturn – even if it seemed more interested in supporting its new Game Boy Color than the N64.

Guardian Heroes

So it comes as no surprise that during the last months of 1997, and continuing on into 1998, Sega Saturn lost its ground. Even outstanding releases such as Guardian Heroes

and the Panzer Dragoon

series weren’t up to snuff when compared with the onslaught of games the PlayStation was showing. In autumn of 1998, Sega unleashed their new sixth generation console in Japan: the Dreamcast. Although it was only released in Europe the following year, many previous Sega’s enthusiasts had already turned their back on the company. In their eyes, Sony’s PlayStation was the impressive new kid in a town the Sega Saturn had already left.

Cheap, easy, popular

Piracy has always been a big issue in Europe, and the Demoscene owes a lot to European hackers in the 80s. Since then, games and other media were increasingly copied without the authorization of their original owners. Piracy wasn’t just an annoyance, it was common.

Then consoles appeared, bringing with them better antipiracy protection due cartridges. Until then, computer disks and taped content were fairly easy to duplicate. Consoles such as the Master System, Mega Drive and Game Boy have contributed indirectly to the downsizing of piracy. But while games couldn’t be so easily copied, consoles could. “Famiclones” were arriving by the hundreds in South and Eastern Europe, introducing consoles (and Nintendo games, in particular) to a larger audience. What is curious in all of this is the appearance of two Mega Drives clones, right in front of Sega of

Europe’s eyes. The first, called Scorpion 16, was even advertised during the TV Show Bad Influence

in the UK, in 1994. The other, called Mega Games II, was a Sega Mega Drive clone sold in the Iberian Peninsula by Ecofilmes, albeit with Sega of Europe’s official blessing.

Mega Game II

By the mid-nineties, multimedia computers equipped with CD-ROM writers were becoming affordable, and soon enough, consoles were also using CDs as their main storage units. This meant that games could be easily copied, and no console benefited more from this than the PlayStation.

“When consoles arrived in Spain, they only got popular later on. One of the key factors was they were impossible to duplicate the game, thus (not easy to copy).”

- Paco Pastor

ELPSA (European Leisure Software Publisher’s Association) reported in 2000 that piracy had cost the UK video games industry an estimated £3 billion in 1999 alone, with PlayStation games at the forefront.

“The way we come to a £3 billion figure is based in the fact that for every legitimate that is sold, there are ten PlayStation titles that are being illegally sold, given away or downloaded.”

- Roger Bennet (Director General, ELSPA)

With piracy and the possibility of copying CDs, so grew the popularity of the PlayStation in Europe. The cheapest console also happened to be easier to hack and “acquire games” for, and thus piracy indirectly played a very important role in its popularity and sales

.

A stronghold lost

In the second half of the nineties, Sega lost its hard-earned market control. Whatever good will was built up over the previous years soon crumbled, and Sega’s Europe’s was progressively losing ground. The Mega CD may have been a mixed bag in results, but the 32X was a flat-out flop. Sega of Europe’s people tried to warn their Japanese counterparts – a new strategy had to be devised – but their warnings fell on deaf ears. By 1995, when the Saturn arrived, the company’s position was already fragile.

“I confess; one of the reasons that made me leave Sega España was the strategy that Sega of Japan was taking for Europe. I didn’t think it was the right one.”

- Paco Pastor

The generational shift to 3D was also taking its toll. Many companies didn’t know how to make the most of the new medium, and the results in some cases were disastrous. At the same time, there was also a merging process going on in Europe; as the video game industry was growing, so too were both profits and ambitions. Companies were buying one another up, in order to gain access to competition’s IP. In some cases, developers’ labors of love were now the property of publisher executives. The result was that the original creative forces often didn’t agree with new directions taken, and in many cases developers left the companies that they helped to create. As a result, tragically, many promising IPs lost a bit of their soul. Sega of Europe, too, had made some of these same mistakes. In trying to grow too fast, the company ultimately lost control of the market it helped create.

In 1995, Sega of Europe was supporting seven systems at the same time: Master System, Game Gear, Mega Drive, Sega Pico, Mega CD, 32X and the Sega Saturn. Developers had supported the first three of these quite easily; their architecture was similar, and the risks were lesser. However, with the fifth generation, companies not only needed to update themselves, but account for teams that were growing in size and complexity. Furthermore, this time around Sega couldn’t rely on developers’ already having a background in the new systems’ technical issues. What had made the transition easy from home computer to consoles was now proving a problem. Sega needed to provide easy development tools, but the Saturn SDK was complex and not user friendly, and the learning curve too high. The PlayStation’s SDK, in comparison, was much more intuitive and easy to program for.

Sega also tried to push the console’s multimedia features, releasing the Saturn Video CD Card in Europe. This was a card peripheral that gave the console enhanced video capabilities, and thus, the ability to play movies.

However, this was focused mainly in the UK; and few other countries ever saw compatible titles. Very few movies were available in VCD format; Photo CD applications were scarcer, still. On top of that, at a price of £170, the card was expensive, and support was limited, at best. The few Japanese games that were compatible with the peripheral weren’t even released in Europe.

Not long after, Sega conducted testing of the Sega Saturn Net Link, a peripheral that enabled users to access the Internet through the console. These tests were conducted in Finland, but the results weren’t positive. As the peripheral had already bombed in the US, Sega of Europe opted not to release it.

By early 1996, a quick peek at the console top sales yielded some insights: The most popular games were almost all the arcade conversions from Sega, including Daytona USA, Sega Rally, Sega Worldwide Soccer, Virtua Cop

and Virtua Fighter

, with few third party developers’ games really helping to push the console. In fact, many of them were rushed projects, and thus had a contrary effect on the console’s image, with early games such as Mansion of the Hidden Souls

and Robotica

doing its reputation more harm than good. Sega did have decent offerings – Clockwork Knight, Theme Park

, and Mortal Kombat 2

were all good games – but they didn’t move sales as much as they could. Furthermore, the definitive Sonic

title was nowhere to be seen; Sonic 3D, Sonic Jam

and Sonic R

may have had their appeal, but none was a decisive system seller. Eventually, gamers got tired of waiting, and moved on to other systems.

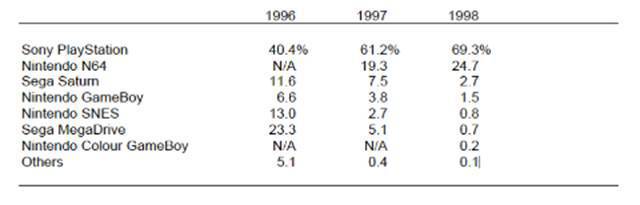

On July 22, 1997, Marketing Week magazine ran a report titled ”SEGA plots attack on game giants,” which mentioned that Sega in that year, in the UK alone, had sold 90,000 Sega Saturn units worth £11.7 million. Sony, by contrast, had moved 1.2 million PlayStations (£163 million), while Nintendo had sold 600,000 N64s units (£84 million).

UK Game Console Market Share

In 1998, Sega of Europe was seeing results best described as merely

decent. It seemed that in the fifth generation their biggest achievement had been helping create the blueprint for the PlayStation’s success in Europe. Many of Sega’s historical accomplishments probably had helped the competition more than the Saturn, itself. Sega helped birth the video game console market in Europe. It ran edgier marketing campaigns, improved the market position of Europe’s third party developers. And, it introduced Sony Imagesoft to European developers. Sega may have planted the tree, but Sony collected the fruit. If PlayStation was big in Europe during the fifth generation, it was mostly on its own merit; but an unofficial debt of gratitude is owed to everything that Sega indirectly did to pave the path.

Sony Imagesoft logo

A new cast

Entering 1998, Sega Europe’s operations encountered major turbulence, having clearly lost the advantage it held in the territory. Whatever the Mega Drive, Master System and Game Gear had accomplished, it was fading away at an alarming rate. The company’s future in Europe was for the very first time in doubt. By then, everyone knew that Sega was releasing a new console in Japan somewhere at the end of the year; and, as such, the Saturn was headed for retirement. Europeans were divided; some were anxious to see what Sega was preparing, others were suspicious of the company and its plans. After all, the combined disappointments of the Mega CD, 32X and Sega Saturn had taken their toll. In less than five years, Sega had introduced three systems – on average, releasing a new platform every 18 months. To make things worse, they didn’t really meet the expectations. Sega’s reputation in Europe was very fragile, indeed.

In spite of this, some stayed true to Sega. The Saturn may have driven away mainstream audiences, but others were still enjoying the console and its games. A niche of Saturn supporters somehow sprang up, helping sustain sales until the end of the year, when Sega of Europe released its official numbers: Roughly 1.5 million Sega Saturn consoles had been sold in the entire territory during 1995-1998.

Preparing for the Dreamcast’s debut, Sega of Europe decided on some cosmetic changes, starting with the logo. Instead of an orange spiral logo, the European version was blue; some speculated that Sega of Europe wanted to avoid a probable trademark infringement with German game/DVD publisher Tivola, which also sported an orange spiral as its logo. Using a blue logo also made sense, as Sega had always had an association with the color. This, however, this didn’t go well with the other branches. The western marketing plan was to create total awareness of the Dreamcast brand, and even a small change – like the color – could compromise the entire operation.

“It was just indicative of the complete lack of integration there was – the Dreamcast logo was blue in Europe instead of orange, the concept of a globalized brand, just evaded the Japanese completely. And Jean-François, who was the general manager in Europe, went his own way, and had his own positioning.”

- Peter Moore (President and COO, Sega of America)

Nevertheless, both western markets were targeted at practically the same time. Sega Dreamcast arrived in North America on the symbolic date of 9-9-1999, and Europe was expected to be 9-23-1999.

A year before, in November of 1998, Sega of Europe had undergone some major changes, with Jean-Francois Cecillon appointed CEO to oversee all of the company’s major operations in France, Germany, Spain and the UK. The press dubbed him “Sega’s Napoleon.”

“Sega became very strong in the early 90s and I think got carried away a bit. So if we are successful this time, I am determined we will avoid making the same mistakes. There will be no huge increase in headcount and structure. We still have a strong brand as a result of previous advertising. This time I think we will focus the marketing work on the product, not the Sega name.”

- Jean-Francois Cecillon (CEO, Sega of Europe)

Cecillon had worked in EMI records in the UK and Ireland, and saw that the music and video game markets were similar. They reached the same audiences, and had to be ready to adjust to change rather quickly. During his first months as CEO, he brought new blood into the marketing department. One of his first moves was to hire Giles Thomas – known for his work at MTV Networks – and make him responsible for advertising, public

relationships and marketing across all major European markets. The first priority was damage control. Sega of Europe had been losing market control since 1996, and had been forced to close several offices, including Austria, Benelux, and Switzerland. The Saturn had given a glimpse of Sega’s future, and the entirety of its European operations were losing money as a result.

In 1998, early drafts of the Dreamcast marketing campaign were drawn up with the consent of Sega of Japan. It was a go-or-bust moment. By 1999, Sega of Europe announced to BBC News Online that their marketing budget for the console advertising would be £60m for the first year alone. The Dreamcast’s launch plans mimicked the past strategy that had worked for the Mega Drive: get to market before the competition, creating a foxhole for the upcoming console war battle. In the eyes of Sega, one of the reasons the Saturn had failed was that it released too close to the PlayStation. If it got onto the market ahead of the competition, the new console would be better positioned to compete. But first of all, audiences needed to be reintroduced to the brand, and – if possible – reminded of how important Sega was to the video game market.

“We are here to launch a brand [Dreamcast] first, a console second. Sega is a very open-minded about the marketing mix. It is looking to do things in an unconventional way.”

- Giles Thomas (Sega of Europe, Marketing Director)

In the next months, Sega rolled out its marketing campaign. The brand was heavily marketed at big events, blockbuster movies premieres, in urban centers and shopping malls, and of course, in edgy TV and magazine ads. September of 1999 was drawing closer.

Giles Thoma

s

Living the dream

With the console already available in Japan, the US and Europe were next in line to enjoy the Dreamcast in 1999. But not everything went smoothly. Sega of Europe commenced its marketing campaigns as early as January of 1999, and the biggest selling point was the console’s online capabilities, with advertisements proudly boasting, “Up to six billion players” and “We all play games, why don’t we play together.” The official European release date for the Dreamcast was just two weeks after it hit in North America. The anticipation for Sega’s new console was so intense that on April 16, 1999, BBC New online reported that “there is a significant number of (grey import) Dreamcast consoles from Japan already in the UK.”

“Marketing at Sega in those days was very much more post-development marketing; the traditional idea of marketing as opposed to marketing these days tends to be very involved in product generation. Now when you talk about marketing you’re thinking about what kind of products should we build, but then I think it was much more developer-push. So some guy would have some technical idea and then you would push it that way as opposed to getting someone right at the beginning say ‘how can we sell this?’”

- Tom Szirtes (Sega of Europe)

Spanish Sega Dreamcast advertisement

Nevertheless, there were some problems. Sega hadn’t learned from the PlayStation’s marketing campaigns, and failed to reach out across all of the

European markets, focusing instead on the traditional mainstays. For all the others, third-party companies were hired to promote the Dreamcast, and given modest budgets to work with. As the release date drew nearer, Sega of Japan – aware of the big expectations for Dreamcast in the US – changed its plans. The production run initially intended for Europe was partially diverted to North America, while the rest would not be available on the expected date, due to “technical issues.” The original European release was delayed by three weeks at the last minute, to October 14, in an effort to focus on the North American launch. Truth be told, the executives in Japan weren’t entirely confident that the upcoming battle could be won in Europe. It was the North American effort that was most important.

French Sega Dreamcast advertisement