CHAPTER 3

The Flea and the Elephant

I do not understand what I do. For what I want

to do, I do not do—but what I hate, I do.

—The Apostle Paul, in Epistle to the Romans 7:15 (NIV)

ONCE UPON A TIME there was a flea who believed that he was king of the world.

One day he decided that he wanted to go to the beach for a swim. But the western shore was many miles away, and on his own, the flea could travel only inches at a time. If he was going to reach the shore during his lifetime, he would need transportation.

So he called out to his elephant. “Ho there, Elephant, let’s go out!”

The flea’s elephant came to his side and kneeled down. The flea hopped up and, pointing to the west, said, “That way—to the beach!”

But the elephant did not go west. He rather felt like taking a stroll in the forest to the east, and that is what he did. The flea, much to his dismay, could do nothing but go along for the ride, and spent the day being smacked in the face by leaves and branches.

The next day, the flea tried to get the elephant to take him to the store to buy salve for his face. Instead, the elephant took a long romp in the northern mountains, terrifying the poor flea so badly that he could not sleep that night. The flea stayed in his bed for days, beset by nightmares of thundering along mountain roads, certain he would fall to his death, and awoke each morning in a cold sweat.

After a week, finally feeling well enough to rise from his bed, the flea beckoned the elephant to his side, clambered up, and said, “I’m not well. Please, take me to the doctor.”

But the elephant merrily trundled off to the western seashore, where he spent the day swimming. The flea nearly drowned.

That night, sitting by the fireplace and trying to warm himself, the flea had a thought. He turned to the elephant and said, “About tomorrow…um, what are your plans?”

You’re probably wondering what the moral of this story is. It is simply this: if you are a flea riding an elephant, before you make any plans, you might want to check out what your elephant has in mind.

This point is more important to your life than it might seem—because in fact, you are a flea riding an elephant. The flea of the story represents your conscious mind, which includes your intellect and power of reason, your ambitions and aspirations, your ideas, thoughts, hopes, and plans. In short, everything you think of as you. And the elephant? That’s your subconscious mind.

To understand how these two work together—or don’t, as is often the case—let’s start with the flea.

Your Brilliant, Amazing Conscious Mind

The human brain is the most remarkable, versatile, powerful creation we know of. Its roughly 100 billion neuron cells pass messages to one another through as many as one quadrillion connections—several thousand times the number of all the known celestial bodies in the Milky Way galaxy. The human brain’s capacity, to put it mildly, is enormous.

Carefully couched within its bony shell, floating in an amniotic-like bath of cerebrospinal fluid atop the impact-cushioning spinal structure, everything about the brain is designed to give it maximum nourishment, care, and protection. Weighing two to three pounds, your brain comprises a mere 1 to 2 percent of your total body weight, yet it consumes 15 percent of your total blood flow, 20 percent of the air you breathe, and some 20 to 30 percent of your body’s total energy intake.

In an average adult brain, approximately 100,000 miles of myelinated axons (functional nerve fibers) are wound like an incredibly complex ball of yarn into a structure resembling a pair of clenched fists. In fact, if you want to get a fair sense of the size and shape of your brain, make two fists right now and hold them up together, knuckles to knuckles.

At its core and base (thumbs, palms, and fingertips) lie the cerebellum, amygdalae, hippocampus, brain stem, and other structures that are in charge of hundreds of thousands of automatic functions, such as balance and motor skills, managing sensory input, and the stress response actions we mentioned in chapter 1. The layers of tissue wrapped around the front and top of the brain (fingers and knuckles), the part involved in conscious thought, is called the prefrontal cortex or frontal lobe.

The frontal lobe is the CEO of the brain, responsible for focus and concentration, for learning and the power of conscious observation. This is the part of the brain that thinks and reasons, the part through which you evaluate options, make new decisions, and exercise your free will. It is the part of you that is reading these words right now, while your brain stem and other more primal centers maintain your breathing, heartbeat, and a myriad of other functions well below the radar of your conscious awareness. If you imagine your body as a gigantic ocean vessel, your frontal lobe is the captain. It decides where you want to go, charts the course, and gives the orders that the thousands of crew members then carry out. This is the conscious brain, the part we think of as “me.”

The frontal lobe is the crown jewel of the human brain. More than our opposable thumbs, bifocal vision, or any other trait, it is the size of our frontal lobe in relation to the rest of our brain that distinguishes us from other animal species. Frontal lobes in history have penned the words of Shakespeare, the music of Bach, the inventions of Leonardo.

However, for all its brilliance, the conscious brain has its limits—and those limits turn out to be pretty severe.

George Miller, Ph.D., one of the founding fathers of modern cognitive psychology and an authority on human perception, was the first to describe the workings of the brain as an information processor—essentially, a living computer. Dr. Miller’s most famous contribution to cognitive science was the concept of chunking, an aspect of short-term memory. According to Miller, our short-term (that is, conscious) memory is capable of holding about seven “chunks” of information at any one time: for example, seven words, chess positions, faces, or digits. (Dr. Miller’s discovery is sometimes cited as the rationale behind Bell Telephone’s decision to standardize phone numbers as seven digits in length.) It’s something like the juggler spinning plates atop those slender sticks: if the conscious brain tries to hold on to many more than seven details at one time, you will soon see some broken plates on the floor.

But look at what else is going on that the brain has to keep track of! There are millions of physiological processes happening in the body, processes that, if they were to falter or stop altogether, would leave us impaired or dead. Cell metabolism, heart and circulatory function, endocrine adjustments, sensory input (and its simultaneous evaluation for signs of danger), smooth muscle operation at hundreds of thousands of different sites around the body…the scope of the task is staggering. Imagine having to give conscious attention to every single metabolic reaction happening within our digestion and endocrine glands. If the conscious mind were in charge of all these processes, we wouldn’t last ten minutes.

Fortunately, the conscious mind is not the one in charge of it all.

An Undiscovered Continent

The concept of a subconscious mind is a fairly recent thing, although humans have always sensed there was some deeper, unseen force there, lying underneath, behind, or beyond the conscious mind. Since the ancient Greeks, scientists have struggled to figure out exactly how to view the human psyche, a Greek word meaning “mind” or “soul.” Aristotle talked about the imagination (phantasia), as distinct from perception and mind, implying that it was a space within the mind that worked with specific images (phantasma) and combined them to arrive at abstract ideas. Mythologies of all cultures are rich with stories of people tapping a greater wisdom through the imagery arising in their dreams.

During the European Renaissance and “Age of Reason,” the conscious mind was especially exalted. René Descartes’s famous philosophical statement, “I think, therefore I am,” was in part a declaration of the clarity and pure self-awareness of human thought. Several generations later, John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding further championed the idea of man’s complete and transparent self-awareness. But this neat, orderly view did not hold water for long. “At the end of the [nineteenth] century,” as Tor Norretrander writes in The User Illusion, “the notion of the transparent man was severely challenged,” as scientists continued to push the envelope of their observations of the human animal. “Hermann Helmholtz, the German physicist and physiologist, began studying human reactions around 1850…[and] concluded that most of what took place in our heads was unconscious.”

By the end of the nineteenth century, scientists including William James, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Pierre Janet were using the terms unconscious and subconscious in their efforts to explore this territory. It was Sigmund Freud, in his 1899 The Interpretation of Dreams, who most famously recognized that there was a vast and uncharted continent within the human mind that had a huge impact on our lives. Calling it the unconscious mind, Freud began the task of charting this unknown landscape, using what tools he had at his disposal, largely consisting of verbal dialogue and the analysis of dreams, which he termed the “royal road to the unconscious.” (While the term unconscious is still generally preferred in scientific circles and Freud himself publically condemned the term subconscious, the latter term has come to be more widely used in everyday language, so we have opted to use it in this book.)

Freud’s conception of the unconscious mind was generally negative, in the sense that he viewed it as the repository for socially unacceptable wishes and desires, painful and repressed memories, and the like. His contemporaries, notably Pierre Janet and Carl Jung, developed this idea in further directions, as have many different schools of psychology since that time. However, the basic tools of investigation available to these generations of researchers and clinicians did not change or improve significantly—until the 1990s, with the advent of high-tech methods of brain imaging and especially functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

One of the many advantages gained from the new imaging technology was that, unlike the tools of electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG), which were significantly limited to measuring activity near the surface of the brain, the fMRI allowed researchers to look deep within the interior of the brain, paving the way for a new understanding of the sheer scope and complexity of what goes on deep inside our heads. It was as if we had spent a century attempting to explore an entire continent on foot and had suddenly gained access to helicopters, airplanes, and satellite photography.

And what an extraordinary picture it was that began to emerge! The subconscious mind:

- Is responsible for all the thousands of processes and subprocesses of physiological metabolism, functions of which the conscious brain is almost completely oblivious

- Manages and sorts through millions of bits per second of sensory input, of which our conscious brain is aware of only the tiniest slice

- Files, sorts, and maintains a storehouse of memories that, while scientists have still not fully been able to quantify it, probably numbers in the trillions

- Manages bodily functions our conscious brain typically ignores, including the minute and complex details of movement and balance, breathing, blinking, use of hands and fingers, the coordinated complexes of motion involved in walking, talking, driving a car, and so forth

George Miller, who gave us the concept of chunking, also quantified the difference between the operational capacity of the conscious mind and the subconscious mind. According to Dr. Miller, the conscious mind puts out on average between 20 and 40 neuron firings per second, while the subconscious puts out between 20 and 40 million firings per second. In other words, in measuring the activity of the subconscious mind as compared to the conscious mind, we’re looking at a factor of about a million to one.

Which turns out to be roughly the ratio of an elephant’s weight to that of, you guessed it, a flea.

An Iceberg Beneath the Surface

On one wall of our office there hangs a large photo of an iceberg to remind us of this reality of human nature.

On average, roughly one-tenth of an iceberg’s mass appears above water level, which means that about 90 percent of it is below the water’s surface. This is something like how the human mind is arranged, only here the numbers are quite different. In terms of physical tissue, about 15 percent of the brain’s mass is dedicated to conscious processes: close to tip-of-the-iceberg proportions. But in terms of bits of information processing, the conscious mind’s function represents one ten-thousandth of one percent of the brain’s total function.

The brain, in other words, is an iceberg that is 99.9999 percent submerged below our level of conscious awareness.

We can access tiny bits of that submerged portion when we want—for example, when we want to remember what it was we meant to get at the store as we walk its aisles. (Because of chunking, though, if it’s more than about seven items, it might be best to make a list before you go!) Pulling up a picture in your mind’s eye of someone you knew in school, or the house where you grew up. Remembering a phone number.

But you cannot pull up all the phone numbers you know, or the faces of everyone you have ever met, even though they are all in there in the mostly submerged iceberg of your mind. If you could pull all that up at once, your conscious brain would be so flooded with information it would be overwhelmed and useless. It has to focus in order to function.

The conscious mind concentrates on a very narrow spectrum of what is going on in our lives at any given moment. It has the capacity to shift that focus and to initiate a new action—but it typically does not stay involved in the majority of the steps that are involved in taking that action. When you decide to recall something—that phone number, that face from the past—your conscious mind initiates the search. Like the captain on the bridge of an aircraft carrier, it gives the command, but then the command itself is carried out by the crew, that is, your subconscious.

Using your conscious mind is something like standing in the middle of a vast museum at night with all the lights off. There you stand, in pitch blackness, and your conscious mind is the pencil-thin beam of a penlight: you can shine it on any one shelf, any one exhibit, but not on all of them at once.

Which means it can be difficult to know what we really believe.

Beliefs are large patterns of thought. If thoughts themselves are the rush of rainfall down a mountainside, beliefs are the channels in the ground through which the water runs. As we saw in chapter 2, we form our beliefs by building new neural tissue and synaptic connections. To a great extent, they live in the subconscious brain. They are thought subroutines. Like breathing, we can put the focus of our attention on a belief if we try, but 99.9999 percent of the time, like our breathing, we don’t think about our beliefs; we just let them run.

Normally, this works out just fine. But when we have formed beliefs that are in direct conflict with our conscious desires, intentions, values, and goals in life, then, Houston, we have a problem. Because, while the flea may want to go west, if the elephant decides to go east or north, there isn’t much we can do but go along for the ride—and as the flea discovered, the ride can be brutal.

Of Two Minds

The subconscious mind works largely by association. It connects things to other things. In other words, it pays attention to resonance—and it is always working in the background. This means that when we have an experience in our conscious awareness, our subconscious is busy in the background looking for past experiences that resonate with it or that are in some way similar. It’s saying, “What can we draw on to help us deal with this situation?”

Some of this comparative thinking may surface to the level of conscious awareness. Most of it, though, occurs so deep in the subconscious that we aren’t aware of it, and thus we may find ourselves reacting to situations in ways that don’t seem to make any logical sense to us. (Like Clay, the airline pilot hugging the carpet.)

This is the reason the powerful experiences of our early lives can hold such a powerful sway over our present lives: while the flea of our conscious mind pays attention to what is happening right now, the elephant of our subconscious mind is continuously referring back to whatever is familiar in the vast files of our past. Even if the associations or connections are not that easy to see, the subconscious mind is programmed to find those similarities, and it’s extremely clever at doing so.

From a survival standpoint, this strategy makes perfect sense: the best predictor of the future is past experience. If we catch whiff of a scent, sound, or sight that is reminiscent of that hungry tiger we encountered years ago, it’s very useful to pull that memory back out of storage instantly and get those alert messages shooting into the amygdalae and adrenals as quickly as possible. The subconscious can act about a million times faster than the conscious mind—and it does.

But this refer-and-alert strategy is not so helpful if the original information was distorted. Garbage in, garbage out, as computer programmers used to say. If you have a flaw in the original assumption, then anything you base on that assumption will be flawed as well. Thus, if we built a belief based on traumatic or microtraumatic childhood experiences that said, Everyone I get close to will abandon me, or, I am a fraud and a failure, then those are the files our elephant refers to in deciding which way he goes.

Again, the subconscious is extremely adept at finding these clues. The ratio of what we sense—that is, what our subconscious mind takes in—to what we consciously perceive is about one million to one. That’s a lot of information. And if your conscious perceptions and your subconscious conclusions are not in alignment, guess which one overrules the other?

For example, let’s talk about relationships.

You meet someone new. First thing that happens, even before you smile and say, “Can I get that door for you?” is that your subconscious mind is processing millions of bits of information at lightning speed, hunting for all possible similarities between this person and this encounter with everyone and every other encounter in your entire past experience—physical traits, facial expressions, mannerisms, clothing, vocabulary, scents, sounds, anything—and then shooting mini-conclusions to the inner portions of your brain: he’s not safe, you can’t trust him, he might betray you, he slurs his T’s just like that kid who made fun of you in third grade, his eyebrows are just like your dad’s—and remember how your dad always criticized you…

You are most likely not conscious of any of this, but it shades your perceptions in subtle ways—often very subtle. Consciously, you’re thinking, “Hey, he seems like a nice guy.” Subconsciously, millions of synapses are screaming, Don’t get close to this guy, you can’t trust him, he’ll hurt you!

Suddenly you are the flea, thinking you are going to the beach with a new friend—and the elephant is galloping off toward the forest in the opposite direction. And the same thing happens not only in romantic relationships but also in business dealings, in classrooms, in friendships, in human interactions of every type and in every context.

This sheds new light on what happened with Stefanie. The greatest source of difficulty for Stefanie was that she consciously intended to move in one direction, but her subconscious beliefs were taking her in the opposite direction.

You can see the conflict back in her original childhood experience. Trotting home with her quarter in hand, she felt pleased and proud—until her parents’ reaction gave her the message that she should have felt ashamed of what she did, not proud. A similar conflict was alive and well in her as an adult. On the one hand, she worked hard to succeed in her business, her community, and her family life, achieving what she regarded as noble aims—but on the other hand, there was a message still hovering there that said something like, “Whatever it is you think you should be proud of, you should really be ashamed of it.”

The flea of Stefanie’s educated, skilled, very intelligent consciousness was all about creating a successful business that would benefit not only her family but thousands of others as well, making a wonderful contribution to society in the process.

But that’s not the direction her elephant wanted to walk.

Remember Clay, the fighter pilot who was terrified of heights? Clay’s flea was perfectly happy to dine out at the rotating restaurant on the top floor of a tall hotel in his neighborhood. His elephant refused to go near the place.

Using a common expression, we might say of Stefanie that she was “of two minds” concerning success, and that Clay was “of two minds” concerning whether it was safe to be suspended up in the air. And in both cases, this would be the literal truth—two minds: one conscious, one subconscious. The flea and the elephant.

This is why the Four-Step Process starts by asking the exact same question that the flea of our story finally hit on: Which way is that elephant headed? What do we truly, deeply believe?

How Do We Know Where the Elephant Is Headed?

Steve Hopkins has always been such a naturally friendly and sociable guy, you’d never have known he had a problem, but he certainly did.

“When we go out to dinner,” his wife explained as they sat together in our office, “Steve calls ahead to the restaurant to make sure they have our meals ready when we get there. He wants to go in, eat, and get out again as quickly as possible.”

“It’s not that I want to,” added Steve. “I have to.”

A high-ranking sales director with a large, successful company and on his way up in the world, Steve was in a position that required him to interact with people continually. His clients never suspected anything out of the ordinary was going on, but on the inside, Steve suffered through every social event he attended. Whether it was with colleagues, potential clients, or family and friends, Steve desperately wanted to get into the restaurant and out again without spending any more time there than was absolutely necessary. Ideally, he’d be out in minutes and in bed by 8:30.

“I know it drives my wife and my kids crazy,” he said. “Almost as soon as we get somewhere, I’m calling it quits and have to leave. I know it’s strange, and I have no idea where it comes from. It’s just how I am.”

Steve’s elephant was calling the shots, and it was making him miserable. So just where was that elephant headed, and why?

Using a technique we will explore in just a moment, we identified that something significant may have happened to Steve some time between sixth and seventh grade.

“Oh, I know exactly what this was,” he said. “We moved.”

When Steve was eleven his family moved to a new house in a different neighborhood and he began attending a different school. Suddenly he went from being popular to being unknown and alone. Fairly short for his age, he was immediately picked on, and because none of the other kids knew him yet, nobody stuck up for him.

This chapter in Steve’s life did not last forever. Naturally sociable even at that age, Steve was able to adapt and before long had made new friends. But the experience was an asteroid strike that left its mark, and now, as an adult, he was completely panicked about going out into social situations. That eleven-year-old experience was still telling him that he might be picked on and ridiculed.

A classic case of I’m not safe.

We took him through the Four-Step Process. His wife called the next day. “We went to a restaurant last night,” she said excitedly, “and we sat down, ate, and talked—for over an hour.” We continued working with Steve, going back and sorting out a number of distinct early events and dissipating their impact, one by one. A few weeks later his daughter reported, “It’s amazing to see my dad go out socially. We just went out with a group of thirty people the other night—and he lasted all evening!”

Steve soon reported an economic fringe benefit to his new sense of well-being. Because flying commercial airlines had always caused him so much anxiety, he had been spending a small fortune on chartered jets whenever he and his wife had to travel—money he now no longer needed to spend.

Case closed…except that here is where it gets really curious. One day Steve called us to report another change, one he had not anticipated.

Some thirty years earlier, Steve had fallen off a roof during a thunderstorm and broken his neck. Miraculously, he was not paralyzed, and he soon regained full use of his limbs, but he had continued to have problems with his back and neck ever since. Despite working with chiropractors, orthopedic doctors, everyone he could think of, he had been unable to get full relief, and the pain had continued to plague him.

Until now.

“I don’t know what you did,” he told us, “but that chronic pain in my neck and back? It’s gone.”

Of course, it wasn’t what we did, it was what he did: he identified and cleared the trauma, which allowed his fog of distress to finally dissipate.

The problem had been that, while the injury from his fall had healed, the echo of the trauma had not. In the few seconds it took for that terrible accident to occur, an asteroid of fear had ripped through Steve’s being: fear of the fall, fear of dying, fear for his family. His muscles had stored the emotional trauma associated with the injury to that area, and while the event itself was over in moments and the obvious effects of the injury had healed in months, the echo of all of that emotional impact was still encoded in the fabric of Steve’s neuromusculature all these decades later. And, as with David the journalist, working on one issue had also relieved an entirely different issue—because to the subconscious, it was not entirely different, but just another resonant facet of the same issue: I’m not safe.

There was nothing wrong with Steve’s neck muscles, physiologically. But they knew something Steve’s conscious mind did not: they knew what was on the elephant’s mind.

They were part of the elephant’s mind.

Candace Pert, Ph.D., who served for twenty years as section chief on brain chemistry of the clinical neuroscience branch at the National Institutes of Health, is a leading researcher on the relationship of physical and emotional health and trauma.

“People have a hard time discriminating between physical and mental pain,” says Dr. Pert. “Often we are stuck in an unpleasant emotional event from the past that is stored at every level of our nervous system and even on the cellular level. My laboratory research has suggested that all the senses—sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch—are filtered, and memories stored, through the molecules of emotions, mostly the neuropeptides and their receptors, at every level of the bodymind.”

Scientists generally believed that neuropeptides predominately populated the brain, until Dr. Pert and other researchers demonstrated that we have similar neural receptor cells running throughout our bodies, or to put it another way, that intelligence resides throughout our bodies, and not exclusively within the cranium. And that intelligence knows a great deal more than our conscious minds know it knows.

In a sense, muscle memory is really an aspect of our subconscious intelligence. The working of the subconscious, in other words, is not limited exclusively to certain parts of the brain alone but is distributed throughout the body. The muscles and other tissues of the body are, functionally speaking, part of the subconscious mind.

And we can use that body intelligence to learn what our subconscious is really thinking.

Your Body Knows

You’re probably wondering, just how did we suspect that something had happened to Steve when he was in sixth or seventh grade? We used a technique we call neuromuscular feedback.

Often referred to as muscle testing or applied kinesiology, this simple process can tap into a tremendous amount of information that the person being tested may not be consciously aware of, from details on the subject’s health and current state of mind to particulars about his or her own history and family dynamics.

One thing we love about this technique is the utter simplicity of the premise. The basic idea is that the body has an unerringly accurate and complete self-knowledge. On a very primal level, we know a good deal more about ourselves than we think we know. Our sophisticated conscious mind may not have access to that enormous body of knowledge, but our muscles and peripheral nerves do.

In a way, this is common sense. We reveal it in our language. For example, when we are about to give someone some emotionally charged news, whether very good or very bad, we say, “Are you sitting down?” Why? Because we know instinctively that a strong surge of emotion can make our muscles suddenly go slack. You’re probably familiar with the texting shorthand LOL ROTF—laughing out loud, rolling on the floor. In the days before text messaging was popular, we used to say, “I fell out of my chair laughing.”

These are more than mere figures of speech. Strong emotional responses do have instant echoes in our neuromusculature. In fact, scientific studies have shown that the stress evoked by making an untrue statement consistently causes a weakening of the muscles of anywhere from 5 to 15 percent. This is not a huge difference, but it’s distinct enough to be clearly discernable. What’s more, this happens whether or not the person being tested knows consciously that the statement is false.

The conscious mind can play tricks on us—but the body always tells the truth.

As a simple overview, here is how neuromuscular feedback works: you make a declarative statement while holding out your arm, and the person testing you presses down with mild but firm pressure. If your statement is true, your arm will resist the tester’s push and remain in place. But if your statement is false—whether or not you are consciously aware of it—your arm will weaken slightly and give in to the tester’s downward push.

Neuromuscular feedback opens a window to a whole new world of information. Bypassing years of conscious thoughts, concepts, and opinions, it directly reveals our mostly deeply held subconscious beliefs as conveyed through our peripheral nerves and muscles.

Window to the Truth

In our earlier description of that first office visit with Stefanie, we left out one key detail: before going through all her history, we took a few minutes to do some neuromuscular feedback.

When Stefanie’s arm was outstretched, we said, “Something upsetting happened to you when you were five or younger.” Her arm weakened and lowered, giving in to our mild downward pressure, meaning Not true—nothing profoundly upsetting happened when I was five or younger.

“When you were six,” we continued. Another weakening of the arm: no, not at that age either. “When you were seven.” Bingo. Stefanie’s arm now held solid, indicating a resounding yes. Whatever upsetting event it was we were looking for had happened at the age of seven, and her neuromusculature knew it.

Once we had pinpointed the exact age when that asteroid hit Stefanie’s world, she immediately knew what event we were talking about.

As far as Stefanie was concerned, that event surrounding the quarter her aunt had given her was something from her childhood, something long behind her. No big deal, yesterday’s news. But it was not yesterday’s news: her nerve and muscle fibers were still shaking with the emotional impact of the experience. Her conscious mind said, “Hey, no big deal,” but her body was screaming out, “It’s a huge big deal—I’m still upset about it!”

We are all well defended; that’s how we get by. Our remarkable capacity for self-deception allows us to deny reality in order to feel more comfortable in the moment. Neuromuscular feedback slips behind the curtain of denial, behind the façade that says, “Oh, I got over that a long time ago,” and sees clearly what is truly going on deep inside ourselves.

A little later in that same visit, we did some additional neuromuscular feedback to help Stefanie more vividly see what we were seeing. We had her make the statement, “I am CEO of [her company’s name],” and she tested strong. No surprise there. Then we had her make this statement: “I want to be financially successful”—and much to her astonishment, her arm went weak.

We tested her on this: “I want my family to be happy.” She tested strong. It was true. Her flea and her elephant were in agreement: they both wanted that. But when we had her then say, “I want to be happy,” her arm went weak. Her flea wanted her to be happy. Her elephant had other ideas.

How to Do Basic Neuromuscular Feedback

To give yourself a simple demonstration of neuromuscular feedback, all you need is a few minutes together with a willing partner to serve as tester. Your partner does not need to know any background or detail; all they have to do is follow these simple instructions. (We have also provided a brief instructional video on this book’s website: www.codetojoy.com.)

1. First neutralize the system.

In order to ensure that you get accurate results, it is helpful for both the subject (you) and the tester (your friend) to first take a minute to balance your neuromuscular system with a simple breathing exercise. We call this crosshand breathing, and here is how you do it:

- In a seated position, cross your left ankle over your right.

- Place your left hand across your chest, so that the fingers rest over the right side of your collarbone. Then cross your right hand over your left, so that the fingers of your right hand rest over the left side of your collarbone.

- Breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth. As you breathe in, let your tongue touch the roof of your mouth, just behind your front teeth. As you breathe out again, let your tongue rest behind your lower front teeth.

Crosshand Breathing

Continue breathing this way, slow, even, and relaxed, for about two minutes.

You’ll find this not only helps to ensure accurate results in what follows, it also is likely to make you feel significantly clearer and more relaxed. We’ll return to this exercise in the next chapter and learn more about exactly what it and other similar exercises do in the body, and why.

For now, though, let’s go on to master the basics of neuromuscular feedback.

2. Get the feel of it.

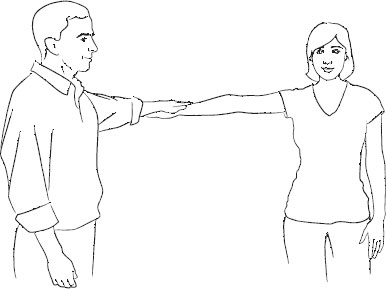

To begin, the two of you stand facing each other. You (the subject) hold one arm straight out to your side, palm down. While you continue holding your arm out straight, your partner (the tester) places the fingers of one hand on top of your wrist and pushes down, gently but firmly, while you resist the downward pressure and try to keep your arm straight.

Neuromuscular Feedback

At first, the tester presses down just firmly enough to feel the extent of your resistance. Neither of you should lock your arm or make an effort to be forceful. Think of this as calibrating the instrument: you’re finding out just how much force it takes to match the tester’s downward push with the subject’s resistance.

It does not matter whether you use your right or left arm. If either arm has any sort of soreness or physical problem, simply use the other arm.

3. Test a true statement.

Have your partner test you while you say, “My name is…,” and state your true name. You should be able easily to maintain your arm straight out as before.

4. Test a false statement.

Now have your partner test you again while you say, “My name is…,” and this time substitute some other name, not your own. In other words, lie. Typically your muscle will be sufficiently weakened that it will not be able to resist the tester’s downward push, and your arm will give way.

5. Test another set of true/false statements.

Take a quick break to shake out your arm for a moment, and then repeat the process.

This time, try a different set of true and false statements: “Today is Monday,” or whatever day it is. Then, “Today is…” some other day, not the correct day.

Note that what you are typically measuring is a decrease in muscle strength of only 5 to 15 percent. Your arm will not collapse dramatically or go completely limp. But you should be able to discern a definite difference. In many cases, the subject will be flat-out unable to keep his or her arm out straight when “testing weak.”

Have some fun with this; try a series of true and false statements. For example, we often use “Two plus two equals four,” followed by “Two plus two equals seven,” or “I am [your age] years old” followed by “I am [some other age] years old.”

You don’t want to overdo it to the point where you tire or strain your arm. But play with it enough to get the feel of the difference between testing strong and testing weak. Again, this is not a test of wills; neither tester nor subject should exert a major effort. The point is not for the tester to force your arm down, but for you both to work together to gauge your arm’s ability to resist.

Now, let’s use this tool to investigate what’s going on for you at a subconscious level. You’ll notice that in our meeting with Stefanie, we used neuromuscular feedback twice: once to pinpoint her negative past experience, and once to pinpoint her self-limiting belief. Let’s now do the same with you, starting with pinpointing that past event.

Using Neuromuscular Feedback to Identify Significant Past Experiences

As you went through chapter 1, you identified a number of events and experiences in your past that may be having a long-term negative impact on your life. You can use neuromuscular feedback to determine which events are most relevant to your current issue or problem.

There may be a number of significant events, but let’s seek to identify the single most significant one, that is, the one experience that has had the strongest negative impact on you.

Starting with your list of significant past events, which you wrote out in chapter 1, now test each event, just as you tested simple statements about your name or the date.

“Grandma died has a significant impact on my present problem.”

“Grandma died does not have a significant impact on my present problem.”

Make sure these are statements, and not questions. Each statement you test should be in the form of a present tense, declarative statement: “This is so,” or “This is not so.”

Once you have identified which events are significant, you can refine your search further:

“Grandma died is having the strongest negative influence in my life right now.”

“Grandma died is not having the strongest negative influence in my life right now.”

In chapter 1, we suggested that you identify each significant negative past event with just a few words. Now you can see how useful this is. It’s far easier to test statements that are short and simple rather than lengthy and involved.

For simplicity’s sake, it is helpful to narrow your search here down to a single past event. Of course, there may well be more than one such event that has had an impact on you, and in time, you can certainly work through all of them. But as you go through the Four-Step Process for your first time, it is helpful to focus on just one past event.

Later, you can come back and go through the process a second time, focusing on a second past event, and a third, and as many times as you want. In Stefanie’s case, we helped her go through and clear three distinct past events, one at a time. In Steve Hopkins’s case, it was six.

But for now, find one to focus on.

Using Neuromuscular Feedback to Identify Your Self-Limiting Beliefs

Once you have gone through the events of your past, you can use the same process to assess the self-limiting beliefs you worked with in chapter 2.

“I am not safe is my strongest self-limiting belief.”

“I am not safe is not my strongest self-limiting belief.”

And so on.

As with the testing of significant past events, you may find more than one self-limiting belief. In fact, chances are good that you will. Most people are dealing with not one but at least two or three of these beliefs. But again, it is most helpful to single out the one most significant belief and work on just that one for now.

Again, as we said in chapter 2, there are no wrong answers here: the Four-Step Process is a very forgiving system. Even if you select a belief that doesn’t perfectly match what is truly going on for you, you’re going to get improvement anyway. It’s just that the more accurately you pinpoint the events that have affected you and the beliefs that are affecting you now, the more rapid and dramatic that improvement will tend to be.

Does This Really Work?

“How do I know this is really working, and the other person isn’t just pushing harder on my arm?” People often ask us this. After all, couldn’t this just be an example of the placebo effect—all in our minds?

It’s a reasonable question. We wondered the same thing ourselves when we first began exploring the process many years ago. But the results of neuromuscular feedback are objectively measurable by the tools and instruments of hard science.

One of the most striking confirmations of neuromuscular feedback appeared more than a decade ago, in a 1999 study conducted by Daniel Monti, M.D., a professor at Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College. Monti and his colleagues took a group of eighty-nine medical students and systematically had them say true and false statements. (In the language of the study, they were “exposed to congruous and incongruous semantic stimuli.”)

There was no human factor involved in making the measurements. Instead, they used computerized dynamometers (an instrument that measures power output) to measure the force exerted on the subjects’ deltoid (shoulder) muscles. Muscle response, as measured by these purely objective physical instruments, was consistently some 17 percent weaker when the subjects made incongruous (that is, false) statements.

As we mentioned, this process is not meant to be a test of brute strength. Still, we once had an interesting opportunity to test the sheer physical limits of the procedure when we had a visit from one of the world’s strongest athletes, whom we will call Dan.

A former NFL lineman, Dan ranked at the time as the number two power lifter in the world. He had flown in from the East Coast to participate in an international competition in California. During his visit, we asked if we might do some simple neuromuscular feedback, and he readily agreed.

Dan was the biggest man either of us had ever seen up close. When he held out his arm for us to test, it felt like we were putting our hand on a tree trunk. At our direction, he stated his name. Not surprisingly, we could not budge his arm. (The man has the power of a horse.) Then, again at our direction, he again stated what his name was, but this time he gave a fictitious identity. We easily pushed his arm down.

He couldn’t believe it. He was convinced it was a trick. “Let me try that again,” he said. We did. This time, he tried with all his might to keep his arm outstretched. He simply could not do it.

That is the beauty of muscle testing: it’s simple, and it works.

Trouble-Shooting

“What if my tester can’t feel any difference?”

Make sure your tester waits just a moment after you make the statement, before gently applying pressure. Also make sure this is gentle, gradual downward pressure, and not an immediate or abrupt pushing.

“What if our results seem unclear or inconsistent?”

Make sure you are focusing on the statement you are testing, and not simply saying it out loud while thinking about something or someone else. Neuromuscular feedback will work just as well whether you speak your statement out loud or simply think it silently—so if you are thinking strongly about something else while you make a verbal statement, it could confuse the results.

It’s best for subject and tester not to look each other in the eye while testing, as it’s too easy for the tester to look for subtle cues in the subject’s face. The tester should strive to be a neutral agent here, acting purely as an objective, mechanical arm.

If you have concerns about the tester’s objectivity concerning your past events and limiting beliefs, or if you feel uncomfortable speaking these various beliefs out loud in front of your tester, you can always test these statements by making them silently. In that case, you can tell the tester you will make a silent statement in your mind, and that you will nod to them when it’s time for them to test. This way, they will not even know what statement they are testing.

“What if our answers come out backward—for example, if ‘Two plus two equals seven’ tests strong instead of weak?”

If you’re getting a clear distinction, but it’s opposite from what it should be, then have both of you sit and do another two minutes of crosshand breathing to ensure that your systems are balanced and neutral.

If you are still not getting clear results after doing this, then leave it for now and go on to the next chapter. We will look at more techniques for clearing and balancing your system in chapter 4, and you may want to wait until you go through those and then come back to explore neuromuscular feedback at that point.

“What if I don’t have anyone I can get to be my testing partner?”

Although it takes time and practice, it is possible to act as your own tester. We have provided an overview of how to do this on our website, www.codetojoy.com.

However, it’s also important to understand that, while neuromuscular feedback is a powerful and valuable tool, it isn’t absolutely essential here. If you don’t have anyone to partner with at the moment, you can still effectively practice every step of the Four-Step Process.

In fact, there are three basic tools you have that will help you gauge which are the specific past negative events and present self-limiting beliefs you want to deal with:

1. The evidence of your life

To an extent, we can see what our deeply held beliefs are simply by looking at the results in our lives. We may say we are ready for a long-term, committed relationship (that’s the flea talking) and be mystified every time yet another relationship blows up in our face (the elephant).

This requires being willing to take an honest look at your life. What is the true state of your relationships, your health, your work, your career?

2. Your own gut sense

Nobody knows yourself better than you do. And even though the conscious mind is unaware of more than 99 percent of what is going on in the subconscious, you are subconsciously aware of all of it, 100 percent.

How do you feel as you greet each new day?

3. Feedback from others

While it’s true that nobody knows us better than we do ourselves, it is also true that we tend to have blind spots—and sometimes these occur in the areas we most need to see clearly. The people around us, especially those who are close to us, may have the benefit of objectivity.

Just as family members may know of traumatic early events that you have no memory of, there may be family and/or friends who have a truer picture of some of the beliefs that run your life. They may, in other words, more clearly see your elephant than you do.

The Problem with Positive Thinking

Understanding the enormous disparity between the conscious and subconscious functions—the communication gap between flea and elephant, you might say—helps to explain the profound limitations of counseling and other forms of cognitive therapy. When it comes to that persistent and pervasive fog of distress, as we said in the introduction, talking it through just doesn’t provide much help.

We have often heard people say, as we explore their history and look at past events that may be causing them distress, “Oh, I already dealt with that in therapy.” And indeed, they may have felt better when talking about it and may have even seen some improvements in their lives as a result. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, though, they have dealt with the issue only on a conscious level—and that is like dealing with the foam on the top of an ocean wave, not the powerful currents deep underneath. It is the subconscious level that really determines the feeling state.

This is why popular approaches to self-improvement, such as positive thinking and affirmations, are so rarely as effective as their adherents hope they will be. Remember, the conscious attention functions something like a penlight in a vast, dark room: it is a powerful little beam, but it can only illuminate the one tiny area where you shine it—and it only illuminates that tiny area while you’re shining it there. As soon as you move the beam to light up something else, that first area slips back into darkness. You can put all your heart and soul into consciously thinking, “I deserve love, I deserve love, I deserve love…”—and then the moment you go back to your normal routines and are no longer focusing the flashlight of your prefrontal cortex on that thought, your subconscious routines kick in with their one-million-times-more-powerful message: I am worthless and unlovable.

The problem with positive thinking is that, while it may be positive, it’s still thinking. And that is using the power of a flea to divert the path of an elephant.

This is not to say that there is no value in focusing on our conscious awareness. There are good conscious techniques that can be quite helpful, which is why cognitive behavioral therapy does have value. When you pay careful attention (conscious awareness) to how you are thinking about things, it can change your emotional state. It’s something like learning to play a musical instrument, learning a new language, or learning anything new: you have to focus on it consciously at first, practicing it until it starts to become a habit.

The problem is that, when we are dealing with these profoundly ingrained, emotionally charged belief structures that have been seared into our nervous systems by the asteroid strikes of early traumatic experiences, they are tough to change. It is something like bending spring steel: as long as you hold it in that new position, it stays there—but the moment you let go, it springs back to its former shape. In order to effect a genuine and lasting change in these deeply held beliefs, we need to address them at the deepest cellular level.

That is the purpose of step 2, which we’ll explore in the next chapter.