11

Cleisthenes and Athenian Democracy (508/7)

CHAPTER CONTENTS

11.1 Cleisthenes and His Opposition 154

11.2 Cleisthenes’ Reforms (508/7) 156

11.3 Cleisthenes Enfranchises Athenian Residents WEB50

11.4 Membership in the Deme 160

11.5 Ostracism (Ostrakismos) 161

11.6 Ath. Pol. on Ostracism and the Dating of Its Introduction WEB50

11.7 Generalship 163

11.8 Athenian Public Building ca. 500 WEB52

This chapter discusses the establishment of democracy in Athens following tyranny. It documents the struggles of the Alcmeonid Cleisthenes with his domestic and foreign foes, and describes his reforms that gave power to the people. The chapter then examines the nature of the Athenian township (demos), which was a building block in Cleisthenes’ reconstruction of the city administration. Finally, it reports on two measures that were associated, rightly or wrongly, with Cleisthenes: ostracism and the creation of the office of general (strategos).

Athenian democracy, and Cleisthenes’ reforms that contributed to it, was born out of a domestic conflict that spilled over into clashes with other states. The two chief sources for Cleisthenes’ reforms are Herodotus and Ath. Pol., which differ over their date. While Herodotus (5.66.1–2) dates Cleisthenes’ reforms to the period of his struggle with Isagoras, Ath. Pol. (21.1) dates them to its aftermath in 508/7, and the majority of scholars agree with the latter version. Both sources depict the rivalry between the leaders as a typical aristocratic contest, in which each man was helped by his respective hetaireia (companionship). In later times, and especially in the late fifth century, hetaireiai were groups of men of similar age and elite background who aided their members in politics and litigation. The nature of these associations in the late Archaic period is poorly attested, but they might have resembled the fellowships that supported Peisistratus and his rivals prior to his tyranny. Combining the testimonies of both Herodotus and Ath. Pol. suggests that Cleisthenes initially lost ground to Isagoras. In response, he imitated the tyrants by reaching out for popular support and expanded his group of friends to include the people (demos). Isagoras called in his Spartan friends, and it was ultimately the Council’s and people’s resistance to Isagoras and his Spartan allies that decided the struggle in Cleisthenes’ favor. The evidence is insufficient, however, to settle the scholarly debate between those who see the workings of a spontaneous popular revolution and others who doubt the extent of the people’s power or ability to act without guidance from the elite and Cleisthenes. In any case Cleisthenes’ democratic reforms institutionalized the rising power of non-elite Athenians.

11.1 Cleisthenes and His Opposition

Herodotus 5.66.1–67.1, 69.2–70.2, 72.1–73.1

(5.66.1) Athens, great before, became greater when delivered from her tyrants, and the two men who had power in the city were Cleisthenes, an Alcmeonid, who is reputed to have bribed the Pythian priestess, and Isagoras son of Tisandrus. Although Isagoras came from a respected family, what his precise origins were I am unable to say, but his kinsmen sacrifice to Carian Zeus.1 (66.2) These men were locked in a struggle for power, and when Cleisthenes began to lose he proceeded to associate himself [prosetairizetai] with the common people. Later he divided the Athenians, who initially had four tribes, into ten, and changed their names. Formerly they were called after the sons of Ion – Geleon, Aegicores, Argades, and Hoples – but Cleisthenes created for them names taken from other heros native to the land. Ajax was an exception, and he added him because, though a foreigner, he had been a neighbor and ally.2

(67.1) In this, I think, Cleisthenes was following his own grandfather on his mother’s side, Cleisthenes, tyrant of Sicyon.

Notes

1. Elite families were often recognized by the cult they worshipped and controlled.

2. Ajax came from the island of Salamis. For the selection of tribal names, see Ath. Pol. 21.5: 11.2.

Herodotus goes on to discuss the tribal reforms of Cleisthenes’ grandfather in Sicyon in support of his own thesis that Cleisthenes changed the Ionian tribal system from four to ten in order to distinguish the Athenians from the Ionians.

(5.69.2) After winning the support of the Athenian common people, which had formerly been given slight regard, Cleisthenes renamed the tribes and increased their number. He appointed ten tribe-leaders [phylarchoi] in place of the earlier four, and assigned demes to each tribe; and having thus brought the common people to his side he was far stronger than his opponents.

(70.1) Isagoras, now being worsted in his turn, devised the following countermeasure. He called for assistance from Cleomenes of Sparta, who had been a guest-friend [xenos] of his since the siege of the Peisistratids; and Cleomenes was actually accused of having sexual relations with Isagoras’ wife. (70.2) Cleomenes’ first move was to send a herald to Athens to order the expulsion of Cleisthenes and many other Athenians (whom he called “accursed,” an addition to his message made on the instructions of Isagoras). For the Alcmeonids and their partisans stood accused of the killing here referred to, whereas neither Isagoras himself nor his friends had had any part in it…

Herodotus proceeds to recount the Cylon affair and the Alcmeonid curse (see WEB 6.7: “Herodotus on Cylon”).

(5.72.1) When Cleomenes sent orders for the expulsion of Cleisthenes and the “accursed” Athenians, Cleisthenes himself left town. Cleomenes nevertheless appeared in Athens after that with a small detachment, and on his arrival he expelled seven hundred families, which Isagoras identified for him, to remove the curse. He next tried to disband the Council,1 and proceeded to transfer its powers to three hundred of Isagoras’ partisans. (72.2) The Council, however, resisted and would not accept this; and so Cleomenes, along with Isagoras and his supporters, seized the acropolis. The rest of the Athenians then united and blockaded them for two days. On the third, all the Spartans amongst them left the country under the terms of a truce.

(72.3) So it was that the prophetic utterance came true for Cleomenes. For when he mounted the acropolis intending to take possession of it, he approached the temple of the goddess in order to address a prayer to her, but before he passed the doors the priestess arose from her seat and said: “Spartan stranger, go back and do not enter the shrine – Dorians are not allowed in here.” “I am not a Dorian, lady,” Cleomenes replied, “but an Achaean.”2 (72.4) And so, paying no attention to her warning, he carried on with his enterprise, and thus was once more expelled with his Lacedaemonians. As for the others, the Athenians imprisoned them under sentence of death, and they included Timesitheus the Delphian, whose feats of strength and bravery were, as I could tell, very great.3

(73.1) After the execution of the prisoners, the Athenians recalled Cleisthenes and the seven hundred families expelled by Cleomenes. They also sent a delegation to Sardis, since they wanted to form an alliance with the Persians, knowing as they did that they had provoked the Lacedaemonians and Cleomenes into war against them.

Notes

1. The exact identity of the Council is uncertain. It could have been Solon’s Council of 400, Cleisthenes’ new Council of 500, or the Areopagus. The first possibility is more attractive.

2. Cleomenes’ answer is enigmatic. Perhaps he claimed pre-Dorian descent as an Achaean.

3. Regrettably, Herodotus failed to record this man’s story.

In return for a Persian alliance the local satrap in Sardis demanded that the Athenians give the Persian king earth and water as tokens of subjugation. The Athenian envoys agreed but were blamed for it upon their return.

Cleomenes then tried and failed to lead an army of the Peloponnesian League against Athens, which was attacked also by Boeotian and Chalcidian forces (506/5). The Peloponnesians retreated and the Athenians defeated the other invaders. Cleomenes tried once more to make Spartan allies of Athens and her rulers when he planned to restore Hippias to power ca. 505, only to be rebuffed by the Corinthians again (Herodotus 5.90–93: WEB 7.27.III “The Second Corinthian Opposition to King Cleomenes I”). By this time, however, Cleisthenes’ reforms were very much at work.

Questions

1. What led to Cleisthenes’ defeats and later success in his struggle with Isagoras?

2. How did Isagoras resemble Peisistratus?

3. What were the Spartans’ reported motives for intervening in the conflict? What do the motives suggest about the sources, or Spartan foreign policy?

11.2 Cleisthenes’ Reforms (508/7)

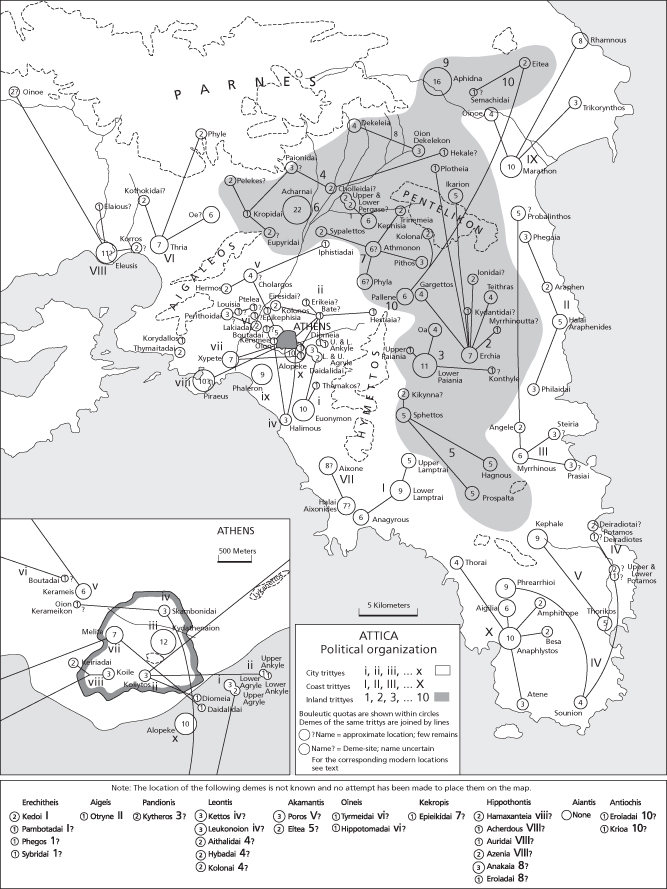

The most informative source on Cleisthenes’ reforms is Ath. Pol. 21. To better understand the account, it is helpful to look at Cleisthenes’ reorganization of the city’s political structure from its basic unit, the demos (deme). Generally, Cleisthenes divided the citizens into demes (townships) that made up larger districts called trittyes (thirds), which in turn comprised larger groups called tribes.

The word demos could mean the entire people, the masses, the rule of the people (democracy), and a local settlement or township. It is the last unit, which scholars have termed “deme,” that formed the basis of Cleisthenes’ reforms. Cleisthenes expanded the basis of citizenship from kinship to include free aliens and other disenfranchised residents who lived in the demes (see Aristotle in WEB 11.3). The new citizens probably supported him in his struggle against Isagoras. Many demes existed prior to Cleisthenes’ reforms, and together with the new demes he created, they now numbered 140. Cleisthenes created thirty districts called trittyes. A trittys might consist of a number of demes, which were not always in close proximity, or of a single deme if it was large enough. Cleisthenes also divided Attica into three regions: city (asty), coast (paralia), and inland (mesogeios). The names resembled those of the regions that supported Peisistratus and his rivals, with the significant exception of the “aristocratic” plain, which now disappeared into the “city” and “inland.” Each region included ten trittyes. Using lots, Cleisthenes joined three trittyes, one from each region, into an artificial body called a tribe (phylê). In other words, a tribe consisted of one trittys from the city, one from the coast, and one from the inland. “Deme,” “tribe,” and “trittys” were old, familiar terms, and Cleisthenes further mitigated his departure from the past by giving each of his ten new tribes an eponymous hero who had a well-established cult and known myths. Yet he changed the substance of tribal affiliation when he transformed the old four-tribes system based on (fictitious) kinship to ten tribes made up of disjointed territories. The four old tribes continued to fulfill religious duties but lost their political powers to the ten new tribes. By making the new tribes the basis for recruiting Council members, troops, and tribal choruses who competed with one another in the city festivals, Cleisthenes fostered solidarity within the new tribes as well as mixing elite and non-elite Athenians in the city’s institutions.

11.2.A Cleisthenes’ Measures

Ath. Pol. 21.1–5

(21.1) It was for these reasons, then, that the demos put their trust in Cleisthenes. At that time he became the leader of the people, and now, three years after the overthrow of the tyrants, and in the archonship of Isagoras [508/7] (21.2) he first of all divided the whole citizen body into ten tribes to replace the four then in existence. His object was to mix them up, so that more people would participate in the government; hence the saying “Do not investigate by tribes,” directed at those wanting to look into people’s families.1

(21.3) Next Cleisthenes established a Council of 500, to replace the existing Council of 400, fifty members coming from each tribe, whereas at the time it was a hundred from each [of the four]. His reason for not organizing the people into twelve tribes was to obviate the use of the already-existing trittys (there being twelve trittyes in the four tribes). That would have meant failing to achieve the mixture of the population that he wanted. (21.4) He also divided up the land amongst the demes, forming thirty units, ten in the area of the city [asty], ten on the coast [paralia], and ten in the inland area [mesogeios]. These units he now termed trittyes, and he assigned three by lot to each tribe so that each would have one part in all three areas.2 And all living in each of the demes he made fellow-demesmen to each other. This was to stop people from using the father’s name in forms of address, thereby exposing the newly enfranchised citizens; instead, they would refer to them by their demes, which is why Athenians use the demes in their nomenclature.3

(21.5) Cleisthenes also appointed demarchs [heads of demes], and these had the same functions as the earlier naukraroi, for he replaced the naukrariai4 with the demes. He gave names to the demes, some of them deriving from their localities but some, too, from the people who founded them, since the demes did not all now have the same geographical location as the place-name. But as far as clans, phratries [brotherhoods], and priesthoods were concerned, he allowed ancestral custom to prevail throughout. As eponymous heroes of the tribes he instituted ten that the Pythian priestess chose from a shortlist of a hundred.

Notes

1. Since the new tribe was a discontinuous territorial unit, inquiring after the family background by tribe would have been unproductive. Yet citizens continued to be identified by their father’s name.

2. Because the number of citizens in each trittys was roughly similar but not equal, there was a chance that the lot would join together three small or large trittyes, thus undermining the principle of similar size among the ten tribes. Perhaps the lot was “assisted,” or was fortuitously fair; in any case, it was considered divinely guided.

3. Cleisthenes’ attempt to allow new citizens to hide their parentage failed. In Athens citizens were identified by their patronymic and deme, for example, Pericles son of Xanthippus of Cholargus.

4. See 6.6 (“A Failed Attempt at Tyranny in Athens: Cylon”) for the naucraries’ possible function.

11.2.B Athenian Demes

Cleisthenes’ reforms had far-reaching outcomes. The link between deme membership and citizenship undercut the advantage of kinship and birth and created greater equality among citizens. Cleisthenes also removed political power from kinship groups and religious organizations such as the clans, phratries, and cults. The influence of regionally based politicians was curbed. The tribes, which functioned as political and military units, required politicians and citizens to take into account “national” rather than local interests. For example, Cleisthenes’ Council (boulê) consisted of 500 members, fifty per tribe, who presided over the Council for one-tenth of the year (prytaneia) as its presidents (prytaneis). The members’ diverse political base and the rotating presidency guaranteed that power in the polis would not be regionally based. (The view that Cleisthenes’ tribal system was geared to insure Alcmeonid influence in three tribes [e.g., Stanton 1990, 148–159] has not gained much support.) Moreover, the new system strengthened the links between the city and the more remote parts of Attica. Finally, the mobilization of hoplites by demes and tribes, as opposed to the old system, significantly increased their numbers and consequently the city’s military power. Indeed, Athens soundly defeated armies from Boeotia and Chalcis that threatened the new regime (Herodotus 5.77).

The Areopagus was the body that legislated measures. However, Cleisthenes did not change property qualifications for public office or diminish the Areopagus’ power to supervise the political system. This was accomplished by later popular leaders who continued the democratization of the city.

Map 11.1 The Athenian demes: Attica political organization. From The Demes of Attica 508/7–ca. 250BC by David Whitehead (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986). © Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

Questions

1. Trace the group affiliations of an Athenian citizen from his family to larger groups. What civic engagement was entailed in each group?

2. Why did Athens become more democratic following Cleisthenes’ reforms?

11.4 Membership in the Deme

The building block of Cleisthenes’ reforms was the deme. As with the polis, the deme had local elected officials such as demarchs, who ran the deme’s assembly, implemented its decisions, and served as treasurers. The deme was in charge of local temples and religious activity, including contributions to the polis’s sacrifices and festivals. Many demes had an agora and a theater. Membership in the deme was hereditary and stayed with a man even if he moved elsewhere in Attica. The deme also served as a military unit and sent members to the Council in proportion to its size within the fifty-member quota allotted to a tribe.

Ath. Pol. describes a late fourth-century procedure for registering and reviewing membership in the deme, whose core may go back to Cleisthenes’ time.

Ath. Pol. 42.1–2

(42.1) The constitution is currently structured as follows. Citizenship is limited to those whose parents are both citizens, and these are registered amongst the deme-members at the age of eighteen.1 At the time of their registration, the deme-members make the decision on their membership by a vote taken under oath. They decide first whether candidates seem to have reached the age prescribed by the law, and if they do not, they rejoin the ranks of the boys, and secondly whether the candidate is free and of legitimate birth. If by their vote they judge him not to be free, he then appeals to the law courts, and the deme-members choose five men from amongst their number to present the case against him. If the court decides that the person has no right to be registered, then the state sells him off; but if he prevails, the deme-members are obliged to register him. (42.2) After this the Council conducts a review of all who have been registered and, in the event of its deciding that someone is younger than eighteen, it fines the deme-members who enrolled him …

Note

1. Prior to Pericles’ law of 451/0, only paternal citizenship was required for granting a man Athenian citizenship.

Questions

1. What were the criteria for Athenian citizenship, and how did the state try to prevent false claims to it?

2. What prevented members of the deme from abusing their power to admit or refuse admittance of new members to their group?

11.5 Ostracism (Ostrakismos)

Ostracism was a procedure that allowed Athenians to exile a citizen for a ten-year period. The term ostrakismos comes from ostrakon (pl. ostraka), a potsherd on which the name of the candidate for ostracism was scratched or, less often, painted. Voting with potsherds was called ostrakophoria. Philochorus (ca. 340–260), the historian and chronograph of Attica (Attidograph), provides useful information about the way ostracism was conducted. Plutarch (Aristides 7.5) has a similar account, though his version that it required a minimum of 6,000 citizens to make the vote valid, and that the man ostracized received the majority of these votes, is preferable to Philochorus’ report. Philochorus’ claim that the term of exile was changed from ten to five years is questionable.

11.5.A Trial by Potsherds

Philochorus FGrHist 328 F 30 (Lexicon Rhet. Cantab.)

Procedure for ostracism: Philochorus describes ostracism in his third book in the following manner:

The people would, before the eighth prytany, hold a preliminary vote on whether they wanted to hold the ostracism.1 When they decided to go ahead, the agora was fenced in with planks, with ten entrances left open through which the people would enter according to their tribes, and put in their ostraka, turning the written face downwards. The nine archons and the Council would preside. When the count of who received most votes was made – the quorum being 6,000 – that individual was obliged, within ten days, to settle any private litigation in which he was involved either as accuser or defendant, and leave the city for ten years (later it became five). He continued to enjoy the income from his own property, but was not allowed to come closer to Athens than Geraestus and the tip of Euboea. Hyperbolus was the only dishonorable man to be ostracized for moral turpitude and not for being suspected of tyrannical aspirations.2 After him the practice was terminated. It originated with Cleisthenes’ legislation, which was designed to enable him, when he brought down the tyrants, to drive out their friends along with them.

Notes

1. Ath. Pol. (43.5) states that the preliminary vote was taken in the sixth prytany. The ostracism took place in the eighth prytany, around February/March.

2. Hyperbolus was ostracized between 416 and 415, when two of his political rivals colluded with their supporters against him: 27.1.D (“Alcibiades and the Ostracism of Hyperbolus”).

Archaeologists have found thousands of discarded ostraka in the agora, the Kerameikos quarter, and the northern slope of the acropolis. The published ostraka show that voters often identified candidates for exile by their names and patronymics, and, at times, by their demes as well. Some motivated Athenians supplemented their vote with unkind words about the candidates for exile.

11.5.B Ostraka

Lang 1990, 134, no. 1065

“This ostrakon says that Xanthippus, son of Ariphron, does the most wrong of the accursed leaders [ prytaneis].”

Xanthippus, who was ostracized in 485/4, was Pericles’ father and married to the Alcmeonid Agariste (II). The curse refers to leaders generally or to his Alcmeonid connection. The ostrakon, in the form of an elegiac couplet, was incised around the foot of a black-glazed vase.

Themistocles played a key role in the Persian War of 480–479. There are more than 2,600 ostraka bearing his name. One hundred and ninety of them were found in a well on the acropolis’ north slope and were written by only fourteen scribes. Although never used, these ostraka show how resourceful Athenians sought to assist illiterate voters, or no less likely influence the vote against this famous politician. The thirteen ostraka in Figure 11.1, all wine cup (kylix) bases, were written by the same hand (“Hand C”).

See WEB 11.6 for Ath. Pol. on ostracized Athenians, as well as for the problems of dating the introduction of ostracism and its role in Athenian democracy.

Figure 11.1 Ostraka with inscription: “Themistocles, son of Neocles.” From M. L. Lang, Ostraka (Agora XXV ) (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), pl. 6, nos. 1211 C–1223 C. Courtesy of the Trustees of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Image not available in this digital edition.

Questions

1. Who made a good candidate for ostracism according to documents in 11.5.A–B and WEB 11.6?

2. What might have facilitated the abuse of the “trial by potsherds”?

3. Was ostracism fair? Was it democratic?

4. Regardless of whether Cleisthenes instituted ostracism, was it in line with his reforms? How?

11.7 Generalship

Another democratic change, which Ath. Pol. 22.2 dates to no earlier than 501/0, involved the election of ten generals (sg. strategos), one per tribe. Some time later, the procedure for electing generals was changed to allow the election of two generals from the same tribe, and in the late fourth century the Athenians elected the generals regardless of their tribal affiliation (Ath. Pol. 61.1).

Starting from 487/6, the Athenians selected nine archons, including the polemarchos (military chief), by lot from a panel of 100 pre-elected candidates. If prior to the election of archons by lot the archon polemarch had higher authority over the generals, it soon became too risky to allow luck to decide who would command the army. Selection by lot also reduced the prestige of the archonship (and consequently that of the Areopagus, which consisted of former archons). The result was a rise in the authority and status of the generals. The office differed from most other magistracies in that there was no limit on reelection to it. This, and the strong link between military and political leadership, made the office of strategos highly attractive for the elite. The people too tended for a long time to elect elite members as generals because of the belief that they had leadership qualifications, experience, and a traditional claim to power.

Ath. Pol. 22.2

First of all, in the fifth year after these [Cleisthenes’ laws] were enacted, in the archonship of Hermocreon [501/0], they instituted the oath for the Council of 500, which they take even today. Then they began electing the generals by tribes, one from each tribe, and the polemarch was in command of the whole army.

See WEB 11.8 for public works at Athens that possibly date from this period and an agora boundary stone.

Review Questions

1. Describe the democratization of Athens following Cleisthenes’ reforms (11.2, 11.5, 11.7, WEB. 11.3, WEB 11.6). In what aspects was Athens not fully democratic even within the group of male adult citizens?

2. Rank in power Athenian political institutions and offices after Cleisthenes (11.2, 11.7).

3. Was stasis (strife) good or bad for Athenian democracy?

4. Compare and contrast Solon’s political and judicial regulations (9.8–9) with the reforms of Cleisthenes (11.2).

5. WEB 11.8 has a link to an image of a stone that marked the boundary between public and private spaces in the Athenian agora. Show how Cleisthenes integrated both spaces in his reforms.

Suggested Readings

Cleisthenes’ rise to power and reforms: Ober 1996, 35–52; 1998b (a people’s revolution); contra: Raaflaub 1998b, 1998c; Samons 1998; G. Anderson 2003, esp. 76–83; see also Develin and Kilmer 1997; Ste Croix 2004, 129–179. Reforming the army: Signor 2000; G. Anderson 2003, 147–157. Demes: Traill 1975, 1986; Osborne 1985a; Whitehead 1986. Ostracism and its ideology: Stanton 1990, 173–186; Forsdyke 2005. Ostraka: Lang 1990. Boundaries of the ostracized: Figueira 1993. Generals and archons: Badian 1971; Fornara 1971; Hamel 1998, 79–87; Mitchell 2000. Athenian public space and new democracy: Camp 2001, 39–47.