38

Philip II of Macedonia (359–336)

CHAPTER CONTENTS

38.1 Philip’s Accession and Challenges to his Rule (359)

38.2 King Archelaus’ Military Reforms (413–399)

38.3 Philip’s Military Reforms and Coinage

38.4 Philip’s Court: Companions and Royal Boys (Pages)

38.5 Philip’s Wives

38.6 Philip and the Third Sacred War (356–346)

38.7 Justin on the Battle of the Crocus Field

38.8 Demosthenes’ War Plan Against Philip (352/1)

38.9 Philip’s Capture of Olynthus (348)

38.10 Demosthenes on a Captive Olynthian Woman (348)

38.11 The Peace of Philocrates and the End of the Third Sacred War (346)

38.12 On the Peace of Philocrates; Isocrates Appeals to Philip

38.13 Athens Proclaims War on Philip (340)

38.14 Demosthenes against Philip; Philip on the Propontis

38.15 The Battle of Chaeronea (338)

38.16 Philip, Elatea, and Chaeronea

38.17 Philip and the Greeks after Chaeronea (338–336)

38.18 Demosthenes’ Eulogy of the Dead of Chaeronea (338)

38.19 The Murder of Philip II (336) and the Royal Tombs at Vergina

38.20 Justin on Philip’s Assassination

38.21 Links of Interest

Philip II of Macedonia was a man who transformed the history of both his country and Greece. The accomplishments of his son Alexander the Great were to a large extent based on the groundwork that Philip had prepared.

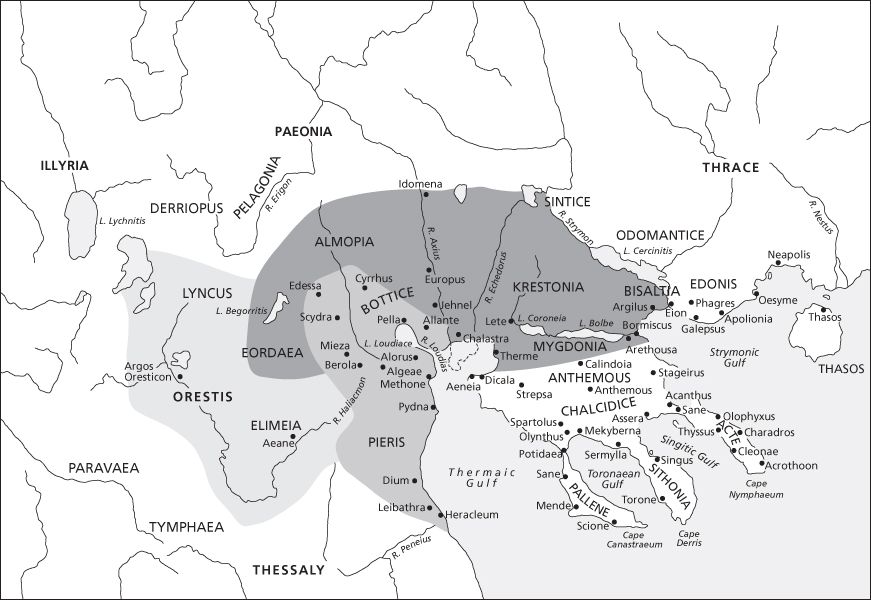

Macedonia was roughly divided into Lower and Upper Macedonia. Its ruler initially dominated only Pieris and most of Bottice. The rest of the Macedonian principalities from Pelagonia in the north to Tymphaea in the south were ruled by local dynasts who acknowledged the authority of the kings only periodically (see Map 38.1).

Before the rise of Philip, many Greeks viewed Macedonia as a peripheral state to be exploited for its timber, minerals, and other resources. The debate about whether the Macedonians were Greek has engaged many more modern people than it did the ancients. The Macedonians spoke a distinct dialect, and some sources – often hostile – called them “barbarians.” Yet Greek attitudes toward the Macedonians and their ethnic identity were changeable; in any case, many accepted the Greekness of the ruling Argead dynasty. The Macedonian royal house claimed Heracles as its ancestor, and although no Macedonian ruler before Alexander the Great seemed to have taken up the title “king,” they certainly acted like kings once they established their rule. Their authority was often challenged from within and without. Macedonia’s neighbors, whether Thracians, Illyrians, Chalcidian towns, Athens, Thessalians, and even rulers of Upper Macedonia, continued to threaten the central government. The result was that the borders of the Macedonian kingdom were highly unstable.

WEB 38.2 describes the military reforms of king Archelaus (413–399) and provides a link to coins from his reign.

The Macedonian army consisted in this period of infantrymen, recruited from the local peasantry, and of cavalry, dominated by the nobility. From at least Philip II’s time, the nobles were called “Companions” (hetairoi). They advised the king and served as his pool of military commanders. Their collective name of Companions denotes their closeness to the king. To elicit similar closeness to the infantry the kings called them “foot-companions” (petzhetairoi). Evidence from the time of Philip and Alexander refers to popular assemblies or to the Macedonians assembled under arms. Scholars are divided about the jurisdiction of these assemblies, with some granting them the power to elect or confirm the election of kings and to serve as a court for treason, and others regarding them as largely impotent.

This chapter focuses on Philip’s reign and accomplishments. It discusses the challenges the king faced upon ascending the throne and how he overcame them. The chapter then reports on Philip’s military reforms, coinage, court, and many wives. Philip’s intervention in Greece is shown through his involvement in the Third Sacred War, the capture of Olynthus, and the peace he signed with Athens in 346. Philip took over Greece after the renewal of the war with Athens and his victory over a Greek coalition at Chaeronea (338). The chapter concludes by documenting Philip’s subsequent settlement of Greek affairs, including the establishment of a Panhellenic league of Corinth, and his assassination in 336.

A link to a small ivory head identified as Philip II can be found in WEB 38.21.

Map 38.1 Ancient Macedonia. From Macedonia from Philip II to the Roman Conquest, ed. R. Ginouvês (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), fig. 15, p. 27.

38.1 Philip’s Accession and Challenges to his Rule (359)

The authority of the Macedonian king depended on his personality no less than on his office. This is why turmoil often followed the death of a king, which in Macedonia was rarely due to natural causes. Chaos and danger also attended Philip’s assumption of power. His brother, Perdiccas III, died in 359 in a battle against an invading Illyrian army, and Perdiccas’ son Amyntas was still a minor. Consequently, Philip became king (and not regent as used to be claimed). Diodorus describes the challenges that Philip faced upon assuming command and how he overcame them. Philip’s modus operandi at this time also characterized much of his later career.

Diodorus of Sicily 16.2.4–3.6; cf. Justin Epitome of Pompeius Trogus’ Philippic History 7.6.3–10

(16.2.4) … Perdiccas, however, was beaten in a great battle by the Illyrians and fell in the engagement. His brother Philip, who had escaped from his situation as hostage, then took over the kingdom, which was in a sad state. (2.5) More than 4,000 Macedonians had been killed in the battle, and the rest, left demoralized and terrified of the forces of the Illyrians, had no will to see the war through to the end. (2.6) At about the same time the Paeonians, close neighbors of Macedonia, began to raid the land out of contempt for the Macedonians; the Illyrians also proceeded to muster strong forces and prepare for a campaign against Macedonia; and a certain Pausanias, who was related to the country’s royal family, was attempting to take over the throne of Macedon through the agency of the king of Thrace. Like them, too, the Athenians were hostile to Philip; they were trying to restore Argaeus to the throne, and had sent off a commander, Mantias, with 3,000 hoplites and a substantial naval force.

(3.1) Because of the military disaster and the immensity of the dangers threatening them, the Macedonians were absolutely at a loss. However, despite all the frightening and dangerous situations facing the country, Philip was not cowed by the magnitude of the anticipated hazards. Instead, he kept the Macedonians together by holding frequent assemblies; and by his shrewd use of language he inspired them to courage and gave them confidence. Furthermore, he took measures to reorder and strengthen the armed forces, and to provide them with appropriate weapons; and he held frequent maneuvers and competitive martial exercises. (3.2) He also developed the tight formation and the equipment of the phalanx, copying the close ordered fighting of the heroes at Troy,1 and was really the first to organize the Macedonian phalanx.

(3.3) He was affable in his interrelationships; he used gifts and promises to win over the crowd to the deepest loyalty to him; and he took shrewd countermeasures against the plethora of dangers bearing down on him. For example, he saw the Athenians focusing all their hopes on the recovery of Amphipolis,2 and trying to restore Argaeus to the throne in pursuit of this end, and so he voluntary retreated from the city – after first making it independent! (3.4) He also sent a deputation to the Paeonians and, after bribing some with gifts and bringing others over by magnanimous assurances, got them to agree to peace for the time being. Similarly, he blocked Pausanias’ return by bribing the [Thracian] king who was on the point of having him restored.

(3.5) The Athenian general Mantias had sailed to Methone and, staying there himself, he sent Argaeus ahead to Aegae with a force of mercenaries. Argaeus came up to the city and called on the people of Aegae to accept his return and become the prime sponsors of his kingship. (3.6) Nobody paid any heed, however, and he returned to Methone. Philip then came on the scene with some of his forces, joined battle with Argaeus, and wiped out large numbers of his mercenaries. The rest took flight to some high ground, and these he released under a truce, taking from them the exiles, whom they delivered to him …

Notes

1. The reference is to Homer Iliad 13.131–133, which is cited by Polybius in 38.3.A below. Both Philip and Alexander modeled themselves on Homeric heroes.

2. Athens lost Amphipolis during the Peloponnesian War but did not renounce its ambition to regain it. Philip withdrew a garrison put there by his brother Perdiccas.

Questions

1. What foreign powers threatened Philip and how did he deal with each of them?

2. What did Philip’s domestic reforms consist of?

3. Which of Archelaus’ projects (WEB 38.2) might still have been serviceable in Philip’s time?

38.3 Philip’s Military Reforms and Coinage

It is likely that Diodorus compressed Philip’s military reforms into a single period and that he credited him with some of his predecessors’ work. The result, however, was the best army of the period.

The main offensive weapon of the Macedonian infantryman, that which gave the Macedonian phalanx its advantage, was the sarissa. This was a pike approximately 4.5–5.5 meters long, weighing about 6 kg, with a spearhead and a butt-spike. The sarissa both outreached the enemy’s spears and provided protection from missiles when held upright. Since it took both hands to wield the pike, Macedonian warriors hung their small shields around their necks, which induced many to renounce their body armor. They also used slashing swords, and occasionally spears and greaves. Alexander’s phalanx, which was likely modeled on that of Philip, consisted of six brigades (sg. taxis) of infantry, each comprising 1,500 men, and an elite brigade of 3,000 (and more) hypaspistai (shield-bearers).

Iron parts from a sarissa apparently belonging to a Macedonian warrior were found in a late fourth-century grave in a cemetery in Aegae (Vergina) (Figure 38.1, p. 524). They include a 0.51-meter-long spearhead, a 0.44-meter-long butt-spike (called sauroter, lit. “lizard-killer”), and a connecting socket that probably joined together the two parts of the shaft, which measured ca. 5 meters.

The second-century historian Polybius discusses phalanx formations and tactics, which probably resembled those of Philip’s army.

Figure 38.1 The metal parts of a sarissa: spearhead, butt-spike, and connecting socket. From the Museum of the Royal Tombs of Aegae, Vergina (BM 3014-16), in D. Pandermalis, Alexander the Great: Treasures from an Epic Era of Hellenism (New York: Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation, 2004), p. 58, fig. 10. Photo: Archaeological Receipts Fund – TAP Service.

Image not available in this digital edition.

38.3.A Phalanx Formations

Polybius 18.29.1–30.4

(18.29.1) Many considerations make it easy to see that, when the phalanx has its usual characteristics and strength, nothing could withstand its head-on charge or hold out against its attack. (29.2) When the ranks close up for battle, a man, with his weapons, takes up three feet of space. The length of the sarissa is, in its original design, sixteen cubits [ca. 7.2 m],1 but this has been reduced to fourteen [ca. 6.3 m] for practical purposes. (29.3) From this fourteen one must deduct four cubits [ca. 1.8 m] for the space between the holder’s hands and the weapon’s counterweight projecting behind him. (29.4) It is therefore clear that the sarissa must extend ten cubits [ca. 4.5 m] in front of each hoplite’s body when he advances on the enemy, holding it before him with both hands. (29.5) It follows from this that the sarissas of the fifth rank, while those of the second, third, and fourth ranks project further than these, still stretch two cubits [ca. 0.9 m] beyond the men in the front line, when the phalanx has its normal pattern and close order in the rear and on the flanks. As Homer puts it:

“Shield pressed against shield, helmet against helmet, and man against man; and when they bent their heads the horns of their horse-hair crested helmets would touch. So close was the order in which they faced each other.” [Iliad 13.131–133]

If my suggestions are accurate and precise, it is clear that every man in the front rank must have five sarissas projecting in front of him, each separated from the other by a space of two cubits.

(30.1) From this it is easy to get an impression of what the advance and charge of the entire phalanx is probably like, and the force that it has, when it is sixteen ranks deep. (30.2) Those behind the fifth rank cannot use their sarissas to engage in the fight. They accordingly do not hold the weapons level (30.3) but keep them up over the shoulders of the ranks before them in order to give protection to the whole formation from above; for the sarissas are massed together and so ward off any projectiles flying over the foremost ranks that can fall on men standing at the rear. (30.4) These men, however, put pressure on those before them in the formation and by their sheer bodily weight increase the force of the charge while at the same time making it impossible for the forward ranks to turn around.

Note

1. The cubit is a Latin term for the Greek pechys, which is the distance between the elbow and the tip of the little finger, ca. 45 cm (18 inches).

The Macedonian cavalry was recruited regionally and in Alexander’s time consisted of eight squadrons (sg. ilê). The royal squadron (ilê basilikê) included mostly nobles and other men close to the king. During Alexander’s campaign it was the cavalry that delivered the decisive blow to the enemy in set-piece battles. They rode without saddles or spurs, and their weapons included spears, body armor, and a helmet. In the Pompeii mosaic depicting the battle of Issus of 333 between Alexander and the Persians, Alexander is shown as a cavalryman dispatching a Persian warrior (see 39.4.B: “The Alexander Mosaic,” p. 561).

In addition to Macedonian infantry and cavalry, Philip employed allies and mercenaries, some of them as light-armed troops and engineers. He was a warrior king, and his frequent use of the Macedonian army helped him to consolidate his power in the kingdom. Conversely, military defeats could and did weaken his position at home.

38.3.B Philip’s Coinage

In 357 Philip captured Amphipolis, which Athens regarded as her own colony. His control of this strategic city became a bone of contention between Athens and Macedonia. Philip, perhaps sincerely, perhaps not, promised to restore it to Athens, but he never did. Athens declared war on Philip but did little to pursue it. In 356 Philip captured the city of Crenides in Thrace and, after adding to it territory and settlers, renamed it Philippi. The polis’ new name suggested the king’s ranking above his subjects and the state, because hitherto foundations of cities were not named after their founder. The possession of Philippi and Amphipolis allowed Philip to mine silver and gold ore in the region and thus to become one of the wealthiest men in Greece. His silver and gold coins soon replaced Athenian coins as the preferred means of exchange. However, Philip was also a great spender, and when he died his son found himself in debt.

Diodorus of Sicily 16.8.6–7

(16.8.6) After this Philip proceeded to the city of Crenides [356]. This he enlarged by adding significant numbers to its population, and he changed its name to Philippi, calling it after himself. He then developed the gold mines in the area, which were hitherto very unproductive and of little importance, to the point where they were able to provide him with an income of more than a thousand talents.1 (8.7) From these mines he swiftly built up his wealth, and he brought the kingdom of Macedon to great preeminence through his abundant riches. For he struck the gold coinage that was known as the Philipeios after him, and then established a considerable force of mercenaries and also used the money to bribe a large number of Greeks to turn traitor to their native lands …

Note

1. In comparison, the Athenians in 425/4 made the (probably dubious) claim that they collected 1,460 talents in contributions from about 400 cities.

There is a link to Philip’s coinage in WEB 38.21.

Questions

1. Compare the phalanx formation to that of the hoplites (8.2–3). How were they similar and how did they differ from each other?

2. What were the phalanx’s vulnerable points?

3. Did the Macedonians benefit from Philip’s use of gold (38.3.B)?

38.4 Philip’s Court: Companions and Royal Boys (Pages)

Philip gained his nobles’ support by giving them land, gifts, commands, and royal posts. Land grants also won him the friendship and services of Greek and Thessalian families. His court in Pella was the political, social, and cultural center of the kingdom. Greeks and barbarians came there as envoys, friends, or seekers of employment and patronage. The fourth-century historian Theopompus of Chios described Philip’s court in his universal history entitled History of Philip (also known as Philippica), which centered on Philip and which survives only in fragments. Theopompus depicted the king negatively, explaining his success as due to the Greeks’ moral decline. Accordingly, his description of Philip’s court appealed to the Greeks’ disapproval of heavy drinking and homosexual relationships between male adults. The Macedonian elite, however, subscribed to different protocols. Polybius, the source of the Theopompus fragment, cites the author as an example of historians who write with bias about kings.

38.4.A Philip’s Companions

Polybius 8.9.1–13 (Theopompus FGrHist 115 FF 27, 225a)

(8.9.1) On this one might level criticism at Theopompus more than anyone. He states at the beginning of his history of Philip that what most induced him to undertake the enterprise was the fact that Europe had never produced anyone who was at all comparable with Philip son of Amyntas.1 (9.2) And yet right after this, in his introduction, and throughout his history, he shows Philip to be completely lacking in self-control as regards women, to the point of doing his best to ruin his own household by his flamboyant passions.2 (9.3) He then reveals the king as being unprincipled and mischievous in his treatment of friends and allies; as one who had subjugated and outfoxed many cities by duplicity and force; (9.4) and as one so passionately fond of drink as to be often seen by his friends clearly inebriated even in the daytime. (9.5) Anyone wishing to read the beginning of Theopompus’ 49th book will be thoroughly shocked by the writer’s eccentricities. Amongst other things he has presumed to make the following statement (I have cited the passage verbatim):

(9.6) “Those amongst the Greeks and barbarians who were depraved and shameless in character would all flock to Macedonia to Philip’s court, where they were saluted as ‘the king’s companions.’ (9.7) For Philip for the most part rejected men of good character who took care of their own property, and showed regard for, and promoted, wastrels and men who spent their lives drinking and dicing. (9.8) He not only supported them in these activities but actually made them into virtuosos in all sorts of iniquitous and repulsive behavior. (9.9) Of disgusting or degrading qualities they lacked none, and of good and upright qualities they possessed none. Some of them spent their time shaving and making their bodies soft, men though they were, and others shamelessly had sex with each other despite being bearded. (9.10) They would go around with two or three of their ‘boyfriends,’ but would themselves also provide the others with the same services as these provided to them. (9.11) So one would have been right in supposing these to be not hetairoi [companions] but hetaerai [prostitutes], and in calling them not soldiers but rent-boys. (9.12) Their nature was to be killers of men [androphonoi], but in practice they were whores of men [andropornoi]. (9.13) Let me put it simply and stop going on at length (says Theopompus), especially since I have so many matters to deal with. It is my opinion that the so-called friends and companions of Philip were worse animals, and worse in character, than the Centaurs that inhabited Pelion, the Lystrygonians living on the plain of Leontini, or any other beasts you care to think of.”3

Notes

1. Polybius’ criticism of Theopompus was perhaps unwarranted, because Theopompus’ statement about Philip’s singularity is ambivalent.

2. The reference is probably to the circumstances attending Philip’s death ( 38.19 ).

3. The Centaurs were mythological creatures who were part human, part horse, and were known for their uncivilized way of life and unbridled conduct. The Lystrygonians were cannibal giants who killed many of Odysseus’ sailors.

Young sons of important local families served as the king’s Royal Boys, or Pages ( paides basilikoi). They were educated with the royal children, attended to the king’s personal needs, and may have been used as hostages to insure their families’ loyalty. Quintus Curtius Rufus, a Roman historian of Alexander the Great, reports on the institution.

38.4.B The Royal Boys or Pages

Q. Curtius Rufus 8.6.2–6

(8.6.2) As was observed above, it was customary for the Macedonian nobility to deliver their grown-up sons to their kings for the performance of duties that differed little from the tasks of slaves. (6.3) They would take turns spending the night on guard at the door of the king’s bedchamber, and it was they who brought in his women by an entrance other than that watched by the armed guards. (6.4) They would also take his horses from the grooms and bring them for him to mount; they were his attendants both on the hunt and in battle, and were highly educated in all the liberal arts. (6.5) It was thought a special honor that they were allowed to sit and eat with the king. No one, apart from the king himself, had the authority to flog them. (6.6) This company served the Macedonians as a kind of seminary for their officers and generals, and from it subsequently came the kings whose descendants were many generations later stripped of power by the Romans.

Questions

1. How did Philip control his Companions, according to Theopompus (38.4.A)?

2. Describe Philip’s court without Theopompus’ moral judgments (38.4.A).

3. What duties did the nobles’ sons owe the king? Do these duties explain their education in military and administrative leadership (38.4.B)? If so, how?

38.5 Philip’s Wives

While the institution of the Royal Boys served to foster ties at home, Philip used marriages to cement alliances abroad. The third-century literary scholar Satyrus listed all of Philip’s wives. In the Macedonian polygamist’s court, the queen was the woman who gave birth to the crown prince. In Philip’s case this was Olympias of Molossia, Epirus, the mother of Alexander (III, the Great). Satyrus’ report belies his own statement that Philip’s marriages were always connected to his military campaigns. The dates of Philip’s marriages, some of which are insecure, are: Phila (359/8), Audata (359/8), Philinna (358), Olympias (357), Nicesipolis (353), Meda (352), and Cleopatra (337).

Athenaeus Learned Conversationalists at Table (Deipnosophistae) 13.557b–e

(13.557b) … Philip had a new wedding with every campaign. In his Life of Philip Satyrus states: “In the twenty-two years of his rule (557c) Philip married the Illyrian Audata, by whom he had a daughter, Cynnane (?), and he also married Phila, sister of Derdas and Machatas. Then, since he wished to extend his realm to include the Thessalian nation, he had children by two Thessalian women, Nicesipolis of Pherae, who bore him Thessalonice, and Philinna of Larissa, by whom he produced Arrhidaeus. In addition, he took possession of the Molossian kingdom by marrying Olympias, by whom he had Alexander and Cleopatra, (557d) and when he took Thrace the Thracian king Cothelas came to him with his daughter Meda and many gifts. After marrying Meda, Philip also took her home to join Olympias as his second wife.

In addition to all these wives he also married Cleopatra, with whom he was in love; she was the daughter of Hippostratus and niece of Attalus. By bringing her home as yet another wife alongside Olympias he made a total shambles of his life. For straightaway, right at the wedding ceremony, Attalus remarked: ‘Well, now we shall certainly see royalty born who are legitimate and not bastards.’ Hearing this, Alexander hurled the cup he had in his hands at Attalus, and Attalus in turn hurled his goblet at Alexander. (557e) After that Olympias took refuge with the Molossians and Alexander with the Illyrians, and Cleopatra presented Philip with a daughter who was called Europa.”

Philip’s Family

Note

1. Scholars disagree on whether Philip fathered a son named Caranus from Cleopatra or from another woman.

Question

1. Reconstruct the network of Philip’s alliances through his marriages.

38.6 Philip and the Third Sacred War (356–346)

What brought Philip to central Greece and eventually made him ruler of Greece were the Third and Fourth Sacred Wars.

During the 360s Delphi supported Sparta in its conflict with Thebes. In the 350s Thebes encouraged the Amphictyonic league of states connected to the oracle of Apollo at Delphi to charge Phocis (where Delphi was located) with sacrilege for cultivating land sacred to Apollo and to fine it. The charge was hardly new, but the Phocian reaction was novel. In 356 the Phocian general Philomelus occupied Delphi, obtained the support of Thebes’ enemies, and built up a mercenary army. The affair escalated into an all-Greek conflict. On the one side stood Thebes, Thessaly, East Locrian communities, and other Greeks representing the Amphictyonic league. On the other side were Phocis and Thebes’ adversaries, namely, Athens and Sparta, which was also charged and fined by the Amphictyonians for sacrilege. In 354/3, Philomelus took the unprecedented action of using Delphi’s sacred treasures to finance his war.

38.6.A The Phocians Pillage Delphi

Diodorus of Sicily 16.30.1–2

(16.30.1) It became clear that the Boeotians were going to fight the Phocians with a mighty force, and Philomelus decided to muster a large number of mercenaries. But the war called for greater expenditure, and he was obliged to lay his hands on the dedicatory offerings and pillage the oracle.1 He increased the pay for his mercenaries by half as much again, and so a large number swiftly came together, many of them responding to the call to arms simply because of the size of the pay. (30.2) Out of respect for the gods, no right-minded man signed up for the campaign, but the worst scoundrels and men who, because of their greed, had only contempt for the gods eagerly joined Philomelus, so that a strong force of men bent on plundering the temple was quickly assembled …

Note

1. Elsewhere Diodorus exonerates Philomelus of the sacrilege (16.56.5), but the present version seems preferable.

Philomelus was victorious against the Amphictyonic coalition, but in 354 he was defeated by the Thebans and took his own life. He was replaced by Onomarchus, who continued to use the sacred treasures and was as successful a general and diplomat as his predecessor. Onomarchus defeated the Boeotians, the Locrians, and then Philip, who in 353 came to help his Thessalian friends in the war. The king, however, recovered and in 352 returned to Thessaly where he was apparently elected as archon of the Thessalian League. Philip then met Onomarchus in the Battle of the Crocus Field off the Gulf of Pegasae. He won the battle, and although Athens saved Phocis from Macedonian conquest, Philip made significant gains. He now controlled Thessaly and its excellent cavalry, earning the status of a champion of a sacred cause and a legitimate player in Greek affairs.

We have two accounts of this battle, one by Diodorus and the other by the late Roman epitomist Justin, who stresses the religious character of Philip’s position and campaign. See WEB 38.7 for Justin’s account of the Battle of the Crocus Field. The following is Diodorus’ account.

38.6.B Diodorus on the Battle of the Crocus Field

Diodorus of Sicily 16.35.3–6

(16.35.3) Later Philip retired to Macedonia, and Onomarchus launched a campaign against Boeotia, defeating the Boeotians in battle and taking the city of Coronea. In Thessaly, Philip, who had recently arrived with his army from Macedonia, opened hostilities against Lycophron, the tyrant of Pherae. (35.4) Being no match for Philip in the field, Lycophron sent for support from his allies the Phocians, promising in return to join the Phocians in effecting a political reorganization of all Thessaly; and Onomarchus swiftly came to his assistance with 20,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry. Philip therefore persuaded the Thessalians to take up the war along with him, and he brought together a total of more than 20,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry.

(35.5) There was a hard-fought battle, from which Philip emerged as victor thanks to Thessalian superiority in cavalry numbers and in courage. Onomarchus fled toward the sea, and it so happened that the Athenian Chares was coasting by with a large number of triremes.1 The result was a massacre of the Phocians. This was because the fugitives stripped off their armor and tried to swim to the triremes, Onomarchus being one of them. (35.6) In the end more than 6,000 Phocians and mercenaries were killed, including the general himself, and no fewer than 3,000 were taken prisoner. Philip hanged Onomarchus, and hurled the others into the sea as men guilty of sacrilege.2

Notes

1. It is likely that Chares came to help the Phocians rather than by accident.

2. The sources provide different accounts about Onomarchus’ death, including that he died at the hands of his troops. If the “general” killed was Onomarchus, Philip might have punished his corpse.

Questions

1. How did the Phocian Philomelus’ use of money (38.6.A) resemble or differ from Philip’s use of gold (38.3.B)?

2. What does Justin’s account of the Battle of the Crocus Field (WEB 38.7) add to Diodorus’ description of the battle (38.6.B)?

38.8 Demosthenes’ War Plan Against Philip (352/1)

In spite of Philip’s military operations in northern and central Greece in the late 350s, neither he nor Athens were interested in fighting each other. The orator Demosthenes, however, thought that Athens should confront the king and, starting from 352/1, he tried to persuade the Athenians that Philip was a threat. His calls remained unheeded until the late 340s. The Athenians did not regard Philip as a viable danger, and Eubulus, who administered the city’s affairs through his control of the Theoric Fund (cf. 35.11), approved of military operations only when they were financially feasible or did not impact the quality of life at home.

The extant assembly and court speeches of Demosthenes provide valuable information about both Philip’s actions and Athens’ reactions. In his assembly speech titled the First Philippic, delivered in 352/1, Demosthenes encourages the Athenians to fight Philip and upbraids them for their apathy. His portrayal of the citizens as indolent and reluctant to act, however, was not always warranted. He criticized the city for making grand albeit futile plans to employ large numbers of mercenaries instead of citizens, yet the expeditionary force he envisioned consisted of only 25 percent citizens, with mercenaries making up the rest. Athenian citizens still answered the call to service, but there was a growing reliance on mercenaries, who were in abundant supply. Demosthenes offered to pay them two obols per day. Mercenaries’ wages varied considerably, but this offer was clearly on the lower scale, hence, Demosthenes’ suggestion that they supplement their wages with plunder. The Athenians, however, did not endorse his plan.

Demosthenes 4 First Philippic 8, 16–17, 19–26, 28–29

(8) Indeed, do not imagine that Philip’s present power is immutably fixed, like divine power. No, even amongst those who seem to be on very good terms with him, men of Athens, there are some who hate him, fear him, and envy him. You must understand that all the reactions to him found in other men are also present in those who are around him. But all these emotions remain subdued at the moment: because of your apathy and idleness – which, I maintain, you should now cast off – they have no way out.

(16) First, Men of Athens, I say we must fit out fifty triremes. Then I say you must resolve to board them and sail them yourselves if needs be. In addition, I urge you to make ready cavalry-transports and freighters to accommodate half our cavalry. (17) These measures must be taken, I think, to counter the lightning attacks he makes from Macedonia against Thermopylae, the Chersonese, Olynthus, and anywhere else he wants to go …

(19) … But more important than this, Men of Athens, I say you should mobilize a force to maintain continuous operations that do him damage. Do not talk to me about ten or twenty thousand mercenaries, or about those huge forces that exist only on paper! I am talking about a force from our city, one that will obey and follow its leader – whether you choose a single general or more, or whether it be one particular individual or anyone else. I further urge you to provide the upkeep for this force. (20) What kind of force will it be, and of what size? Whence will come its upkeep, and how will it be made ready to discharge these duties? I shall explain, going into each of these questions individually. I am talking about mercenaries now, and about how you should avoid what has often done you harm in the past – thinking that everything falls short of what is needed and so opting with your decrees for the greatest projects, but then failing to take even the smallest steps to put them into effect. Instead, you must take those smallest steps and make due provision for them, adding further resources if they seem to fall short. (21) My suggestion is that the troops should total 2,000 men, and that of these 500 should be Athenian. They should be of any age that seems to you appropriate, and should serve for a prescribed period of time, not a long one but just for as long as you think sufficient, in successive tours of duty. The others, I propose, should be mercenaries. Alongside these there should be 200 cavalry, at least 50 being Athenian, thus preserving on campaign the same ratio as there will be in the infantry.1 These should also have cavalry-carrying vessels. (22) Right, then – so what else? Ten swift triremes; for since Philip has a fleet we need speedy triremes so that the force can be secure when under sail. And where is their maintenance to come from? That, too, I shall explain and illustrate after I tell you why I think a force of such a size to be sufficient, and why I recommend that citizens serve in it.

(23) This is why I specify these dimensions, Men of Athens: we do not at present have the capability to raise a force that could face him in battle. Instead, we must play the pirate and apply such tactics to the early stages of our fight with him. Accordingly the force should not be overlarge – we can afford neither the pay nor the support for that – nor yet should it be completely wretched. (24) The reasoning behind my recommendation that citizens be present to take part in the expedition is this. I am told that in earlier days the city maintained in Corinth a mercenary force that Polystratus, Iphicrates, Chabrias, and some others commanded, and that you yourselves served in it.2 And I know from what I have been told that these mercenaries fought alongside you, and you alongside them, and defeated the Spartans. However, ever since mercenary forces on their own have been fighting for you, they have been defeating only your friends and allies, while your enemies have gained more power than they should have. They take a nonchalant look at the war assigned to them by the city and then choose rather to go sailing off to Artabazus or anywhere else, with their general understandably following – for he cannot command them unless he provides their pay.3

(25) What do I propose, then? That you deprive both general and soldiers of their pretexts for doing this by providing them with pay and also by setting alongside them some home-grown soldiers to keep an eye on them. For the way we run things now is ridiculous. Should someone ask, “Men of Athens, do you have peace?” the reply would be, “Of course we don’t – we are fighting a war with Philip.” (26) But have you not been electing from your number ten battalion commanders [taxiarchs], ten generals, ten squadron commanders [phylarchs], and two cavalry commanders? So what are these men doing? Apart from the one man that you send out to the war, the rest are organizing religious processions alongside the public sacrificers [hieropoioi]. Just like those who fashion clay figurines, you are electing your battalion commanders and squadron commanders for the marketplace, not the war.

(28) … Now for the finances. There is upkeep, just the provision of food, which for this force is 90 talents and a bit more. Forty talents will be needed for the swift triremes (twenty minas a month per ship); another forty for two thousand infantrymen, so that each soldier can get ten drachmas a month as a provision-allowance; and twelve talents for the two hundred cavalry, if each man is to get thirty drachmas a month. (29) If anyone thinks that providing supplies for men on active service is a trifling investment, he is mistaken. I know full well that, if this is enacted, the army will itself provide everything else from the proceeds of the war, making up the pay without causing loss to any of the Greeks or the allies. I am willing to join the expedition and am ready to suffer any penalty if this turns out not to be the case …

Notes

1. Unlike mercenaries, citizen soldiers saved the state their wages, but they could serve only for limited periods, hence the need to rotate them.

2. For Iphicrates’ victory near Lechaeum (390), see 31.10 (“Peltasts and the Battle of Lechaeum”). Chabrias defeated a Spartan navy in 376, and Polystratus’ victory is unknown.

3. Artabazus, son of Pharnabazus, was a satrap in Asia Minor who rebelled against the Persian king. Demosthenes refers to the Athenian generals’ need to finance their underfunded expeditions, here by hiring themselves as mercenaries for Artabazus; cf. 35.12 (“Financing Military Operations”).

Questions

1. How did Demosthenes plan to fight Philip? What constraints framed his plan?

2. How did Athens’ methods of financing campaigns (35.9: “Liturgies,” 35.12: “Financing Military Operations”) affect Demosthenes’ view of the struggle with Macedonia?

38.9 Philip’s Capture of Olynthus (348)

Since 432, much of Chalcidice was organized as a federal state centered on the city of Olynthus. The federation was dissolved or greatly weakened by Sparta in 379, but came back to life in the 360s. The Chalcidians’ major adversaries were Macedonia and Athens, and when these states were in conflict the Chalcidians had to pick sides. In 352, fear of Philip’s growing power as well as disagreements within the Chalcidian federation led to a change in its alliance from Philip to Athens and later to supporting pretenders to the Macedonian throne. In response, Philip declared war on Olynthus in 349. The city requested aid from Athens, and in spite of Demosthenes’ best efforts in what are known as his Olynthiac speeches, Athens’ help came too little and too late. The Athenians were more concerned at that time about the island of Euboea, which was nearer and where they fought to maintain their influence against hostile local leaders. Thus Philip was able to beseige Olynthus and capture it in the autumn of 348.

38.9.A Philip’s Capture of Olynthus

Diodorus of Sicily 16.53.2–3

(16.53.2) In this period [348/7] Philip was eager to conquer the cities on the Hellespont, and took Mecyberna and Torone through betrayal and without running any risk.1 He then embarked on a campaign, with a large force, against Olynthus, the greatest of the cities in that area. He initially bested the Olynthians in two engagements and hemmed them in under siege; but while launching a series of attacks on them he lost large numbers of men in battles at the walls. In the end he bribed Euthycrates and Lasthenes, the two foremost Olynthians,2 and took Olynthus after it was betrayed to him through their agency.

(53.3) Philip pillaged the city, enslaved its inhabitants, and sold them off. After doing this he found himself with a lot of money to carry on the war, and he also struck fear into the other states that were opposing him. He rewarded those soldiers who had fought bravely in battle with appropriate prizes and he also distributed largesse to the powerful men in the various cities, thereby providing himself with many men ready to betray their own. And he would himself declare that he had expanded his kingdom by means of gold far more than by arms.

Notes

1. Mecyberna was the harbor of Olynthus. Torone was located on Sithonia in Chalcidice.

2. Euthycrates and Lasthenes were two cavalry commanders who defected with their cavalry to Philip. Their betrayal became notorious.

In WEB 38.10, Demosthenes makes use of Olynthus’ destruction and a story about the abuse of a captive Olynthian woman to attack a political rival.

The tragedy of Olynthus turned out to be a blessing in disguise for excavators. Archaeologists have found in Olynthus sling bullets and arrowheads, some of which bear the name of Philip or of his generals. More importantly, because the city was resettled only in a sporadic way, it has become a primary archaeological source for Greek town planning, private houses, and public buildings in the Classical era. Of course, not all Greek houses looked alike but responded to the specific character of their environment.

38.9.B Plan of an Olynthian House

The “House of Many Colors,” which owes its name to its painted and colored stucco walls, belongs to a common Classical type called the pastas (or portico) house (Figure 38.2, p. 536). Two vertical and horizontal axes divide the house plan almost equally. The house occupies a plot 17 meters by 17 meters. At its center is the courtyard, made up partly of earth floor (l) and partly of cobblestones (i). It served as the main entrance and illuminated the adjacent rooms, although privacy was attained in general at the expense of light. A square altar is built on the court’s west side. The pastas (e) was an additional open space. Rooms (c), (d), (f), and (j) had earth floors. The other rooms had cement floors with a mosaic in room (f), and a central mosaic apparently embedded in the floor of a shallow pool in room (d), which probably served as the andron (men’s dining room). Room (a) was used for manufacturing and coloring woven fabric. Other Greek houses also included commercial production as part of the household economy. Room (h) operated as the kitchen. The use of the rooms was not fixed but changed according to the needs of the family and seasons of the year.

For more information and images of ancient Olynthus, see a link in WEB 38.21.

Questions

1. Why did Philip treat Olynthus as he did?

2. To what extent does Demosthenes’ description of the party in Macedonia (WEB 38.10) resemble Theopompus of Chios’ account of the Macedonian court (38.4.A)? What moral values do both descriptions appeal to?

3. Try to map the domestic activities described by Lysias in his speech concerning the killing of an adulterer (37.12.D: “The Killing of Eratosthenes”) in the space of the Olynthian house (Figure 38.2).

Figure 38.2 Plan of an Olynthian house. © Nick Cahill. Reprinted with kind permission of the author.

Image not available in this digital edition.

38.11 The Peace of Philocrates and the End of the Third Sacred War (346)

Philip’s gains in the Sacred War and Olynthus and his expressed desire to repair his relationship with Athens led to a peace initiative in Athens. After two Athenian embassies, which included the rival politicians Demosthenes and Aeschines, had gone to Macedonia and come back, a third embassy, this time without Demosthenes and Aeschines, went to inform Philip, now in central Greece, about the latest Athenian resolution. (For the resolution, see Demosthenes in WEB 38.12.I, which also describes the background to the Peace of Philocrates and the difficulties faced in reaching it.) When the embassy discovered that Phocis had surrendered to Philip, however, it returned home. The frightened Athenians thought that Philip was about to march on their city and began preparing for a siege. But Philip had no such intention. Instead, he convened the Amphictyonic council to decide how to end the war.

The Peace of Philocrates, named after one of its Athenian proponents, concluded the war and generally confirmed that Athens and Philip would keep what they already held. However, the agreement favored Philip, who gained control over the Amphictyonic council through his and the Thessalian votes, while his opponents and even allies fared much worse. Phocis was ordered to be dissolved, and Athens failed to defend its mainland allies, including Halos. Thebes got very little for its prolonged conflict with Phocis. Philip was arguably now the strongest man in Greece. The following is Diodorus’ account of the Amphictyonic decision that ended the Sacred War.

Diodorus of Sicily 16.59.4–60.5

(16.59.4) Contrary to his expectations, the king had finished off the sacred war without a battle, and he held a council meeting with the Boeotians and Thessalians. He then decided to bring together the council of the Amphictyonies and leave to that body the decision on all matters in question.

(60.1) The council members accordingly decided to make Philip and his descendants members of the Amphictyonic League, holding the two votes that the Phocians held before their defeat. They further ordered that the walls of the three cities in the hands of the Phocians be removed, that the Phocians should have no association with the shrine or the Amphictyonic League, and that they should have no right to acquire either horses or weapons until they paid back the god the amount of money they had plundered.1 Further, those Phocians who had fled, and all others who had participated in the looting of the shrine, were everywhere to be under a curse and outlawed, and (60.2) all the cities of the Phocians were to be razed to the ground and their populations transferred to villages. Each village was to have no more than fifty houses, and the villages were to be no less than a stade’s distance from each other. The Phocians would keep their lands and every year bring to the god sixty talents in tribute, until they paid off the amount of cash officially registered in the shrine at the time of its desecration. In addition, Philip was to put on the Pythian Games, along with the Boeotians and Thessalians, because the Corinthians had joined the Phocians in their religious transgression.2 (60.3) The members of the Amphictyonic League and Philip were to smash the weapons of the Phocians and their mercenaries on rocks, burning the remnants of them, and to sell off their horses. In conformity with these decisions, the members of the Amphictyonic League formulated regulations for the care of the oracle and all other matters pertaining to religious observance, the common peace, and the harmony of the Greek world.

(60.4) After that, when he had assisted the Amphictyonic League in carrying out its resolutions and shown kindness to all, Philip went back to Macedonia, having now not merely acquired a reputation for godliness and excellence as a commander, but also having laid down a solid groundwork for the greatness that he was to achieve. (60.5) For he dearly wished to be appointed the commander-in-chief [strategos autokrator] of Greece and to embark upon the war against Persia, something that was going to come about …

Notes

1. The plundered money was estimated at ca. 10,000 talents, which the Phocians repaid over the years in varied annual installments starting with sixty talents down to ten in the mid-330s.

2. It appears that Corinth lost its votes or privileges in the Amphictyonic League. The Spartans too were expelled from it.

Philip’s clear prominence put him in Isocrates’ sights. In 346, the ninety-year-old Athenian author tailored his plan to save and unify Greece through a war on Persia to fit the Macedonian king. It is uncertain, however, that Philip seriously entertained the idea of a Persian campaign at this time. See WEB 38.12.II for Isocrates’ appeal to Philip to lead a Persian campaign by virtue of his Heraclid ancestry.

Questions

1. What were Philip’s constraints in signing the peace, according to Demosthenes (WEB 38.12.I)?

2. How was Phocis punished for its sacrilege, and what did Philip gain from the Amphictyonic settlement (38.11)?

3. Why, according to Isocrates, should Philip go to war against Persia (WEB 38.12.II)?

38.13 Athens Proclaims War on Philip (340)

Dissatisfaction with the Peace of Philocrates soon emerged in Athens, which politicians tried to use to get rid of their rivals. In 343 Demosthenes prosecuted Aeschines for his conduct as an envoy to Philip, and Aeschines was acquitted by a small majority. Philocrates, the man most associated with the peace, was convicted the same year in an impeachment trial (eisangelia) and went into exile. Demosthenes also intensified his calls to confront Philip (see WEB 38.14.I).

Philip was busy consolidating his power both at home and abroad. In 340 he attacked the city of Perinthus on the Propontis. Perinthus received aid from the Persians and from the city of Byzantium. The Byzantine intervention led Philip to put this city under siege too, and Athens sent a navy to help Byzantium. See WEB 38.14.II for Philip’s siege of Perinthus, which shows advancement in siege warfare, and for the Byzantine and Persian aid to the city.

The Athenian fleet to Byzantium, under the command of Chares, anchored at Hieron on the Asian coast north of Byzantium in order to protect a large number of merchant ships sailing from the Bosporus to the Aegean. Philip, however, took advantage of Chares’ departure for a meeting with Persian satraps and captured the merchant ships. The blow to Athenian imports and manpower enabled Demosthenes to persuade the Athenian assembly to declare war on Philip. We learn of these events from the fourth-century historians Philochorus and Theopompus. They are cited by the first-century Alexandrian scholar Didymus in his commentary on Demosthenes’ speeches, and by the literary critic and historian of Augustus’ time, Dionysus of Halicarnassus. In 339, Philip pulled his forces out of both Perinthus and Byzantium.

38.13.A Philip Seizes Ships to Athens

[Demosthenes] 11.1; Didymus Demosthenes 10.34–11.5 = Theopompus FGrHist 115 F 292; Philochorus FGrHist 328 F 162 = Harding no. 95B

[Demosthenes] 11.1: “It has become clear to you, Men of Athens, that Philip did not establish peace with this but merely postponed the war.”

Didymus: The war the Athenians fought against the Macedonian was kindled … all the other transgressions of Philip against the Athenians while he feigned to be observing the peace, and most of all his campaign against Byzantium and Perinthus. He was eager to have these cities on his side for two reasons: to eliminate the Athenian grain supply, and to prevent the Athenians from having cities on the coast for their fleet and from possessing in advance operational bases and places of refuge for the war against him. He then brought off his most lawless action: he seized the ships of the traders at Hieron. In Philochorus’ account, these numbered 230, but in Theopompus’ 180; and from the ships he raised a total of 700 talents. According to other sources, and Philochorus in particular, these events took place in the archonship of Theophrastus [340/39], whose term followed that of Nichomachus. Philochorus’ account runs as follows:

“Chares went off to a meeting of the commanders of the Persian king and left ships at Hieron to gather up the freighters from the Pontus. When Philip saw that Chares was no longer there, he initially tried to send ships to seize the freighters, but, unable to take them by force, he shipped troops over to Hieron and took possession of the freighters there.”

38.13.B Philip and Athens Go to War

Dionysus of Halicarnasus To Ammaeus 1.741F. = Philochorus FGrHist 328 F 56a = Harding no. 96A

The two sides went to war with each claiming to have been wronged by the other. Philochorus, in his Attica Book Six, is very precise in his account of the reasons for this, as he is concerning the time at which they broke the peace, and I shall cite the most important elements from this work.

Theophrastus of Halae. It was during his archonship [340/39] that Philip first sailed up and attacked Perinthus. Failing in that venture, he next blockaded Byzantium, bringing up siege-engines.

Philochorus then goes through all the charges Philip leveled against the Athenians in the letter, and adds the following (which I quote verbatim): “After they heard the letter and Demosthenes inciting them to war and proposing decrees, the people voted to tear down the stele that had been erected commemorating the peace and alliance with Philip, to man their ships, and put all other war measures into effect.”

Questions

1. Why did Philip attack Perinthus and Byzantium, according to Didymus (38.13.A)?

2. According to Demosthenes, what were the arguments for peace in Athens, what stood behind them, and why should they be rejected (WEB 38.14.I)?

3. What were Philip’s tactics and instruments of war in the siege of Perinthus (WEB 38.14.II)?

38.15 The Battle of Chaeronea (338)

What led Philip back to central Greece and eventually to the decisive battlefield of Chaeronea was the Fourth Sacred War of 340/39. Following an Amphictyonic invitation to fight Locrian Amphissa, Philip came with his army and occupied Elatea in Phocis. This was perceived as a threat both in Boeotia and in Attica. See WEB 38.16.I for Philip’s capture of Elatea and the reaction to it in Athens.

Demosthenes recommended forming an alliance with Thebes against Philip. He went to Thebes with nine other envoys and had not only to compete against Philip’s offer of an alliance, but also to overcome the mutual animosity that frequently characterized the relationship between the two states. Demosthenes regarded (and presented) his success in forming an alliance with Thebes as a crowning achievement, but it came at a price. Athens promised to help Thebes secure its rule over Boeotia, pay for two thirds of the expenses of the coalition army and all the expenses of the joint navy, and give seniority in command to the Thebans.

Following intensive diplomatic activity and small-scale military operations, including Philip’s punishment of Amphissa for its sacrilege, the two sides faced each other on the battlefield of Chaeronea in Boeotia in early August 338. On one side were Philip and his allies, and on the other forces from Boeotia, Athens, Euboea, Megara, Corinth, Achaea, Leucas, and Corcyra. Chaeronea is considered one of the most decisive battles in Greek history. For many modern historians it marks the end of the Classical Age and the beginning of the Hellenistic Age when the Greek poleis of the mainland lost much of their independence. It is unfortunate, however, that we are not well informed about the fighting. The two chief sources for the battle are Diodorus of Sicily and the second-century CE Macedonian author Polyaenus, who wrote a didactic military work entitled Strategmata (stratagems). Diodorus commences his description of the battle following a report that Philip failed to convince the Boeotians to move to his side.

38.15.A Diodorus on the Battle of Chaeronea

Diodorus of Sicily 16.85.5–86.6

(18.85.5) After this Philip failed to gain an alliance with the Boeotians; even so, he decided to take on the fight against both of them [i.e., the Boeotians and the Athenians]. After waiting for the latecomers of his allies to arrive, he came into Boeotia at the head of more than 30,000 infantry and no fewer than 2,000 horse.1 (85.6) Both sides were ready for battle, both were psychologically prepared and full of spirit, and both were the other’s equal in courage; but it was the king who had the edge in numbers and leadership qualities. (85.7) Having fought many different kinds of battle, emerging victorious from most encounters, he had extensive experience in the conduct of warfare. On the Athenian side the finest commanders were dead – Iphicrates and Chabrias, and Timotheus as well – and of those remaining the best was Chares, who was in no way superior to your ordinary, run-of-the-mill officers in terms of action and judgment in military leadership.

(86.1) The two forces were drawn up at break of day. On one of the wings the king stationed his son Alexander, in years just a boy, but distinguished for courage and speed in action, and he set beside him his most outstanding officers. Philip himself took charge of the other wing, keeping with him his elite troops, and the other squadrons he deployed in order as circumstances dictated. (86.2) The Athenians arranged their line-division by nationality, giving one part to the Boeotians and themselves assuming command of the rest. The battle was hard fought for a long time, with large numbers falling on both sides, and for a while the struggle still offered both sides hope of victory.

(86.3) Alexander, however, was eager to demonstrate his personal courage to his father, and he did not lay aside his overpowering greed for glory. With many of his brave soldiers fighting alongside him, he first of all breached the dense front of the enemy line and, felling large numbers, put heavy pressure on the troops ranged against him. (86.4) Since his companions did the same, the enemy front was repeatedly being broken. As the pile of bodies kept rising, Alexander, ahead of the others, forced his way through and drove back the enemy. After this, the king himself came to the forefront of the battle, refusing to concede credit for the victory even to Alexander. First of all he thrust back those deployed in front of him, and then, by also forcing them to take flight, he became the author of the victory. (86.5) Of the Athenians more than a thousand fell in battle, and no fewer than two thousand were taken prisoner. (86.6) Many of the Boeotians, too, were killed, and not a few were captured. After the battle Philip erected a trophy and gave up the bodies for burial. Then he offered victory sacrifices to the gods and made appropriate awards to those who had performed valiantly.

Note

1. The size of the army that opposed Philip is uncertain. In addition to citizen troops, it included between 10,000 and 15,000 mercenaries and 1,000–2,000 cavalry. Scholars estimate their totals at between 30,000 and 35,000 men.

38.15.B Polyaenus on the Battle of Chaeronea

Polyaenus Stratagems 4.2.2, 4.2.7

(4.2.2) Drawn up against the Athenians at Chaeronea, Philip was retreating and giving ground before them when Stratocles the Athenian commander shouted out, “We must not stop piling on the pressure until we bottle up the enemy in Macedonia,” and he would not halt his pursuit.

“The Athenians do not know how to win,” said Philip, and he gave ground gradually, keeping the phalanx in tight formation, and sheltered by shields. In a short time he gained some higher ground and, encouraging the rank and file, he turned and vigorously attacked the Athenians. And after putting up a superb fight he won the victory.

(4.2.7) At Chaeronea Philip was aware that the Athenians were hotheaded and poorly trained, while the Macedonians were disciplined and well trained. He therefore drew out the battle, swiftly sapping the Athenians’ strength and making them easy to defeat.

38.15.C Plutarch on the Battle of Chaeronea

Plutarch reports on Alexander’s role in the attack in his biography of the king.

Plutarch Alexander 9.2

Alexander was also present at Chaeronea and took part in the battle against the Greeks, and it is said that it was he who was the first to burst into the Sacred Band of the Thebans. Even down to our time they show near the Cephisus River an old oak, called “Alexander’s Oak,” near which he encamped on that occasion, and not far from it is the communal grave of the Macedonians.

38.15.D Reconstructing the Battle

Scholars have offered different reconstructions of the battle and the positions of the opposing sides. One suggestion is that Philip commanded the Macedonian right wing and Alexander the left. At first Philip approached the enemy with his line at an oblique angle, but when the enemy attacked he feigned a retreat (see Polyaenus above). This provoked the Athenians into pursuit, which created a gap in the Greek front, and which Alexander exploited when he charged the Thebans at the head of the Macedonian cavalry. At about the same time, Philip reversed to attack the Athenians, and he and Alexander (now on foot fighting the Sacred Band) brought the battle to a conclusion. This is N.G.L. Hammond’s reconstruction of the battle (1973, 534–557). See Figure 38.3.

Figure 38.3 Plan of the battle of Chaeronea. From Macedonian State by N.G.L. Hammond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), fig. 5, p. 117. Reprinted with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Image not available in this digital edition.

It should be said, however, that no source mentions Alexander leading the cavalry into battle, or, as has been suggested, that he commanded the entire left-wing phalanx against the Sacred Band (Rahe 1981). An alternative view dissociates the monument of the Macedonian dead from the battle’s reconstruction and positions the Thebans on the left against Philip (Ma 2008, 74). See WEB 38.16.II for the likely Macedonian and Theban monuments commemorating the battle of Chaeronea. WEB 38.18 includes Demosthenes’ eulogy of the Athenian dead of Chaeronea and his patriotic depiction of the battle.

Questions

1. What was the reaction in Athens to the news about Philip at Elatea, and what qualified Demosthenes to save the day? What did he do (WEB 38.16.I)?

2. What advantages did Philip have over his opponents in Chaeronea (38.15.A–C)?

38.17 Philip and the Greeks after Chaeronea (338–336)

Following Chaeronea Philip moved to regulate his relationship with the Greeks and settle their affairs. He must now have been planning his campaign against Persia and hoped to encourage the Greeks to support it, or to prevent them from spoiling it. In general, Philip’s hegemony over the Greeks was not oppressive. He treated each city-state or group of peoples on an individual basis, favoring some, punishing others, so that they would have little in common. For example, Athens was a well-fortified city with a strong navy that could be used against the Persians, so Philip gave back the Athenians their dead and prisoners-of-war without ransom and allowed them to retain some of their holdings in the Aegean. But he also forced Athens to give up her empire and territorial claims elsewhere and to become his friend and ally. His treatment of Thebes was very different. He allowed the city’s Boeotian enemies, Plataea, Thespia, and Orchomenus, to rebuild and engineered a change in Thebes’ government to a pro-Macedonian regime, placing a Macedonian garrison in the city’s citadel of the Cadmea. The Greeks called this and other garrisons in Corinth, Ambracia, and later in Euboean Chalcis the “fetters of Greece.” Philip did not wish to fight a second Chaeronea.

Most Greeks acknowledged Philip’s supremacy, except for Sparta, which was punished with loss of territory. In early 337 Philip called a meeting in Corinth at which Greek representatives endorsed a common peace under his leadership. The result was the so-called League of Corinth.

38.17.A The Corinthian League

Diodorus of Sicily 16.89.1–3

(16.89.1) In the archonship of Phrynichus at Athens [337/6], the Romans appointed as consuls Titus Manlius Torquatus and Publius Decius. It was during these men’s terms of office that king Philip, swollen-headed from his victory at Chaeronea, and having now stunned the most famous city-states, began to aspire to becoming leader of all Greece. (89.2) He put out the word that he wanted to conduct a war against the Persians on behalf of the Greeks, and make them pay for their lawless treatment of the temples [under Xerxes], and by this he won their loyalty and good will. He showed kindness to everybody on the private as well as the public level, and to the city-states he made a show of wanting to discuss their interests.

(89.3) A general assembly was therefore brought together in Corinth, and there Philip discussed the war against Persia, holding out to them great hopes and thereby pushing the delegates to support a war. Finally, the Greeks chose him as a commander-in-chief [strategos autokrator] of Greece, and he proceeded to make large-scale preparations for the campaign against the Persians. He fixed the number of troops for each city to contribute to the alliance and then returned to Macedonia.

Two fragmentary inscriptions found in Athens tell more about the oath taken by the Greeks. The numerals next to the names in the second fragment may represent the number of votes each state had in the council.

38.17.B The Greeks’ Oath on a Common Peace

The Greeks’ Oath IG II2 236 = Harding no. 99 = R&O no. 76

A

[Oath. I swear by Zeus, Ge (Earth), Helios (Sun), Pos]eidon, A[thena, Ares and by all gods and goddess]es. I shall abide [by the peace and shall not break] the treaty [(5)…] nor shall I bear weapons [to do harm against those who keep the oaths, neither by land] nor by sea. [And] I shall not capture [any city nor a fo]rt [nor a harbor in order to make w]ar, of any of those who participate (10) in the [peace] by any device [or plot; nor] shall I overthrow the kingdom of Ph[ilip and his descendant]s, not the [existing constitutions] in each state when they swore [the oaths regarding] the peace; (15) [nor shall I myself do anything] contrary to these [agreements nor] shall I allow any one else as far as it is [in my power. And if any one does anything] to breach [the agreements, I shall give aid] as requested by [those who are wronged], and I shall make war against (20) the one who transgresses [the common peace] as [resolved by the common Coun]cil [synhedrion] and the hegemon; and I shall not abandon […]

B

[..] 5 […] [The]ssalians: 5. … ]ans: 2. … ]iots: 1. [Samothracians and] Thasians: 2. ] … ans: 2. Ambraciot[s: 1 (?)]. ] … f]rom Thrace and […]. Phocians: 3. Locrians: 3. … Oet]aeans and Malians and [Aenianians … Ag]raeans and Dolopians: 5. … Pe]rrhaebians: 2. Acynthu]s and Cephallenia: 3.

An assembly speech, whose attribution to Demosthenes is uncertain, includes charges against Alexander the Great for violating his agreement with the Greeks. Some of the charges refer to obligations under the treaty. Even if the treaty was with Alexander, it is likely that it was based on a former treaty with Philip. The speech and the above inscription show that the treaty resembled other common peace treaties that ordained the cessation of war and local autonomy under a hegemonic control. But the treaty with Alexander (and the one with Philip if its reconstruction above is correct) also differed from previous peaces in their insistence on preserving the status quo within the polis. It also provided a mechanism to enforce the peace.

38.17.C Alexander’s Treaty with the Greeks

[Demosthenes] 17 On the Treaty with Alexander 6, 8, 10, 15, 16, 19–20

(6) Such a situation cannot be permitted if you want to maintain justice; for there is an additional statement in the peace accords that anyone behaving as Alexander has behaved is to be treated as an enemy – and his country along with him – by all participants in the peace, and that these should all make war on him. So if we follow the terms of the treaty, we shall treat as an enemy the man who restored the exiles.

(8) Moreover, the treaty explicitly states at the beginning that the Greeks must be free and autonomous. So how is it not truly absurd that the statement that they be free and autonomous should stand at the head of the accords, while the man who led them into servitude is not regarded as having contravened our common accords? So, Men of Athens, if we are to stand by the accords and our oaths, and to take the just course that they require – as I just called on you to take – then it is incumbent on you to take up arms and launch a campaign, alongside those who are willing to join us, against those who have broken the treaty.

(10) I come now to another point of justice relating to the accords. There is a clause in them to the effect that any who subvert the constitutions that existed in the various states at the time when they took the oaths ratifying the peace treaty – these men are to be considered enemies by all participants in the treaty. Consider this, Men of Athens. The Achaeans in the Peloponnese had democratic governments, but the Macedonian has subverted the democracy in Pellene, driving out most of its citizens; and he has turned their property over to their slaves and installed Chaeron the wrestler as tyrant.

(15) But there’s something even more ridiculous. Amongst the accords is the stipulation that members of the Council [synedrion] and those responsible for public safety are to insure that in the states that are signatories to the peace treaty there be no killings or banishment in contravention of the laws established in the cities. There are to be no confiscations of property, either, no redistribution of land, no canceling of debts, and no emancipation of slaves to promote revolution …

(16) I will point out another violation of the treaty. It is stated that exiles are not permitted to make cities that are participants in the peace treaty their base of operations for an armed assault on any of the cities that are signatories to the treaty …

(19) None of the Greeks is ever going to reproach you with having in any way breached the common accords; in fact, they will be thankful to you for having been the only people to point the finger at those guilty of doing this. And so you may be more certain of this fact, I shall merely touch upon some minor points relevant to the issue, though there is much that can be said.

It is stated in the agreement that all signatories to the peace treaty may sail the seas, with no one obstructing them or forcing a vessel to shore. Anyone contravening this is to be considered an enemy by the signatories to the peace. (20) Well, Men of Athens, you have very clearly observed such actions taken by the Macedonians…

Figure 38.4 The Philippeum. © Netfalls/Shutterstock.

38.17.D The Philippeum

In addition to regulating his relationship with the Greeks, Philip sought to enhance his stature among them. This was probably the purpose of his building the Philippeum at Olympia (Figure 38.4). This monument stood on what was prime real estate near the most popular entrance to the sanctuary of Olympia next to the Temple of Hera. It was a tholos building made of limestone and marble and consisting of a circular colonnade of eighteen Ionic columns. The rotunda enclosed a circular interior with nine Corinthian half-columns used for decorative purposes. Inside were statues of Philip, his parents Amyntas (III) and Eurydice, his wife Olympias, and his son Alexander. The sculptor was Leochares, who used gold for the statues’ attire and ivory (Pausanias Description of Greece 5.17.4, 20.9–10) or marble (archaeologists, including Schultz 2007) for the flesh. Philip may have wished to display thus the continuity, legitimacy, and authority of his dynastic rule. Yet the shrine-like structure also suggests his desire to accord himself and his family superhuman, if not divine, status.

Questions

1. Describe the goals, institutions, and officials of the League of Corinth (38.17.A–C).

2. Compare the speech on Alexander’s treaty with the Greeks (38.17.C) with the Greeks’ oath on the common peace (38.17.B). Which peace terms in the oath does the speech confirm? Which does it add?

3. What did the Greeks gain from Philip’s common peace (38.17.A–C)?

4. What themes are highlighted in the commemorations of Chaeronea and its aftermath (38.17.D, WEB 38.16.II, WEB 38.18)?

38.19 The Murder of Philip II (336) and the Royal Tombs at Vergina

Philip returned to Macedonia to plan his Persian campaign and even sent an advanced force into Asia Minor. The preparations were cut short, however, by his assassination in the summer of 336. Unnatural deaths of political leaders have always encouraged allegations of conspiracy, and Philip’s death is no exception.

In 337 Philip married his seventh wife, the Macedonian Cleopatra. At the wedding banquet Cleopatra’s uncle, Attalus, questioned Alexander’s legitimate birth. The incident led to a conflict between Alexander and Philip and the exile of the young prince and his mother Olympias (see 38.5 for Philip’s wives). The sources agree that Philip married Cleopatra for love, although some scholars have detected behind the marriage Philip’s desire to replace Alexander with an heir from his new wife.

The murder of Philip took place during the celebration of the marriage of his daughter and Alexander’s sister, (a different) Cleopatra, to Olympias’ brother, Alexander of Epirus. Philip used the occasion to officially launch the campaign against Persia. Delegations arrived from all over Greece (Athens included) to pay honor to the king. The celebration included games, banquets for the guests, and a procession in which Philip’s statue was carried among statues of the Olympic gods, thus demonstrating his claim to divine status. Diodorus’ description of the event includes reports (omitted here) of omens that foretold Philip’s death and which the self-confident king failed to understand.

38.19.A The Death of Philip II

Diodorus of Sicily 16.92.5–94.4

(16.92.5) Eventually the drinking party broke up, and the games were due to start the next day. It was still dark when the crowds moved hastily to the theater and at daybreak the procession took place in which Philip put on display, along with all the other paraphernalia, statues of the twelve gods, superbly crafted and amazingly decked out in rich splendor. But with these he also displayed a thirteenth image that was appropriate for a god, one of Philip himself – the king was actually showing himself seated among the twelve gods.

(93.1) The theater was full when Philip himself came in wearing a white cloak. He had given orders for his bodyguards to follow him at some remove, for he was showing the world that he had the universal goodwill of the Greeks to safeguard him and needed no protection from bodyguards. (93.2) While he was basking in such success and while everybody was showering praise and congratulations on the man, there suddenly appeared – unexpectedly and completely out of the blue – a plot against the king, followed by his death. (93.3) To make my account of these events clearer, I shall preface it with the reasons for the plot.

Pausanias was a Macedonian by birth who came from the area called Orestes. He was a bodyguard of the king, and because of his good looks he had become Philip’s lover. (93.4) When Pausanias saw another Pausanias – the man had the same name – receiving Philip’s amorous attentions he used insulting language to him, saying that he was effeminate and ready to submit to sex with anyone who wanted him. (93.5) The fellow could not bear such malicious abuse, but for the moment he held his tongue. Then, after informing Attalus,1 one of his friends, about what he was going to do, he committed suicide in an extraordinary manner. (93.6) For, a few days later, when Philip was in combat with king Pleurias of the Illyrians, this second Pausanias stood before the king and on his own body took all the wounds aimed at the king, dying in the act.

(93.7) The event gained notoriety. Then Attalus, who was one of Philip’s courtiers and had great influence with the king, invited Pausanias to dinner, and there poured large quantities of neat wine into him and handed him to muleteers for them to abuse his body in a drunken orgy. (93.8) When Pausanias sobered up after the drinking bout, he was deeply hurt by the physical outrage and charged Attalus before the king. Philip, too, was angered by the enormity of the deed, but he was unwilling to show his disapproval because of his close ties with Attalus and because he needed his services at that time. (93.9) Attalus, in fact, was the nephew of the Cleopatra who had become the king’s new wife, and he had been chosen as commander of the force that was being sent ahead into Asia – he was a man of courage on the battlefield. Thus the king preferred to mollify Pausanias’ legitimate anger over what he had endured, and he bestowed on him substantial gifts and promoted him to positions of honor in the bodyguard.2

(94.1) The resentment of Pausanias, however, remained unchanged, and he passionately longed for revenge not only on the perpetrator of the deed but also on the man who failed to exact punishment for him. The sophist Hermocrates also greatly helped him decide to take action. Pausanias had studied under Hermocrates, and during his schooling had asked him how one could gain great fame. The sophist replied that it was by killing a man who had accomplished great deeds, since the person who brought off the killing would become part of posterity’s memory of the man. (94.2) Pausanias took the remark in the context of his personal indignation and, his anger brooking no delay in the plan, scheduled his enterprise for the upcoming games.