To lay before you the marvellous book of the entire

universe, and have you read the excellence of its

Author in the living letters of its creatures.

—Luis de Granada, The Symbol of Faith

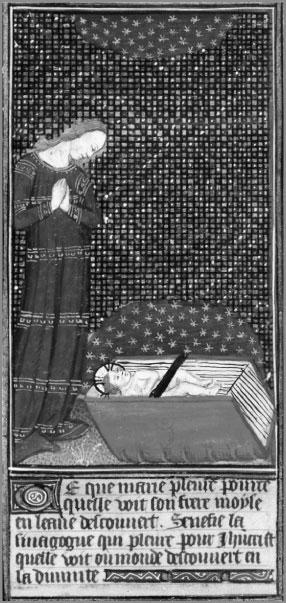

In the left margin of a fifteenth-century French manuscript,¹ a small illumination serves as incipit for the text. It shows, against a dark blue sky studded with golden stars, a woman looking upon a baby child strapped to its cradle. The scene depicted is Moses in the bulrushes. The woman is Miriam, Moses’s sister, who convinces the Pharaoh’s daughter to have the child Moses nursed by a Jewish nurse; unbeknownst to the princess, the nurse is Jochebed, Moses’s mother. The child in the illumination is Moses himself; the basket in which he is sent downriver is a thick, red, bound book. In an effort to ally the teachings of the New Testament with those of the Old, medieval commentators traced parallels between the two, providing artists and sermonists with a rich iconography. The Virgin Mary mirrored Moses’s mother, who regained her youth after her hundred and fifty- sixth year and married her husband Amram a second time: Mary’s virginity was read as equivalent to Jochebed’s new virginal state. Like the angel who announced to Mary the birth of Christ, God told Amram that his wife would bear a child whose memory “would be celebrated while the world lasts, and not only among the Hebrews, but among strangers also.” To escape the Pharaoh’s edict that decreed the slaughter of all Hebrew male children (as Herod would later, in Mary’s time), Jochebed made a cradle out of bulrushes, daubed it with pitch on the outside, and abandoned it on the shores of the Red Sea.² The image is taken up in the exquisite illumination, combining in one depiction the reenactment of the scene in Exodus, Miriam watching over the child Moses as Mary will later watch over the infant Jesus, and the promise that the Book will carry Moses into the world, implicitly announcing the coming of the Savior. The Book is the vessel that allows the word of God to travel through the world, and those readers who follow it become pilgrims in the deepest, truest sense.

Moses in a book, Grandes Heures de Rohan (c. 1430–1435).

Courtesy the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The book is many things. As a repository of memory, a means of overcoming the constraints of time and space, a site for reflection and creativity, an archive of the experience of ourselves and others, a source of illumination, happiness, and sometimes consolation, a chronicle of events past, present, and future, a mirror, a companion, a teacher, a conjuring-up of the dead, an amusement, the book in its many incarnations, from clay tablet to electronic page, has long served as a metaphor for many of our essential concepts and undertakings. Almost since the invention of writing, more than five thousand years ago, the signs that stood for words that expressed (or attempted to express) our thinking appeared to its users as models or images for things as intricate and aimless, as concrete or as abstract as the world in which we live and even life itself. Very quickly, the first scribes must have realized the magical properties of their new craft. For those who had mastered its code, the art of writing allowed the faithful transmission of lengthy texts so that the messenger had no longer to rely solely on his or her memory; it lent authority to the text set down, perhaps for no other reason than that its material existence now offered the spoken word a tangible reality—and, at the same time, by manipulating that assumption, allowed for this authority to be distorted or undermined; it helped organize and render coherent intricacies of reasoning that often became lost in speech, whether in convolutions of monologues or in the ramifications of dialogue. Perhaps we cannot imagine today what it must have felt like for people accustomed to requiring the bodily presence of a live speaker to suddenly receive, in a clump of clay, the voice of a distant friend or a long dead king. It is not surprising that such a miraculous instrument should appear in the mind of these early readers as the metaphorical manifestation of other miracles, of the inconceivable universe, and of their unintelligible lives.

The remnants of Mesopotamian literature bear witness to both the sense of marvel of the scribes and the extraordinary uses to which the new craft was put. For example, in The Epic of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, composed sometime in the twenty-first century B.C.E., the poet explains that writing was invented as a means of properly conveying a text of many words. “Because the mouth of the messenger was too full, and he was therefore unable to deliver the message, Enmerkar molded a piece of clay and fixed the words upon it. Before that day, it had not been possible for words to cleave to clay.” This capacious quality was complemented by that of trustworthiness, as affirmed by the author of a hymn in the twentieth century B.C.E.: “I am a meticulous scribe who leaves nothing out,” he assures his readers, heralding the future promises of journalists and historians. At the same time, the possibility of manipulating this same trustworthiness is attested by another scribe, serving under the Akkadian king Ashurbanipal, in the seventh century B.C.E.: “Everything that will not please the king, I shall delete,” the loyal subject declares with disarming frankness.³

All these complex characteristics that allowed a written text to reproduce, in the reader’s eye, the experience of the world, led to the container of the text (the tablet, later the scroll and the codex) being seen as the world itself. The natural human propensity to find in our physical surroundings a sense, a coherence, a narrative, whether through a system of natural laws or through imagined stories, helped translate the vocabulary of the book into a material one, granting God the art that the gods had bestowed upon humankind: the art of writing. Mountains and valleys became part of a divine language that we were meant to unravel, seas and rivers carried a message from the Creator and, as Plotinus taught in the third century, “if we look at the stars as if they were letters, we can, if we know how to decipher this kind of writing, read the future in their configurations.”⁴ The creation of a text on a blank page was assimilated to the creation of the universe in the void, and when Saint John stated in his Gospel that “in the beginning was the Word” he was defining as much his own scribal task as that of the Author Himself. By the seventeenth century, the tropes of God as author and the world as book had become so engrained in the Western imagination that they could be once more taken up and rephrased. In Religio Medici, Sir Thomas Browne made the now commonplace images his own: “Thus there are two books from whence I collect my Divinity. Besides that written one of God, another of his servant Nature, that universal and publik Manuscript, that lies expans’d unto the eyes of all; those that never saw him in the one, have discovered him in the other.”⁵

Though its sources are Mesopotamian, the precise metaphor relating word to world was fixed, in the Jewish tradition, around the sixth century B.C.E. The ancient Jews, lacking for the most part a vocabulary to express abstract ideas, often preferred to use concrete nouns as metaphors for those ideas rather than inventing new words for new concepts, thereby lending these nouns a moral and spiritual meaning.⁶ Thus, for the complex idea of living consciously in the world and attempting to draw from the world its God-given meaning, they borrowed the image of the volume that held God’s word, the Bible or “the Books.” And for the bewildering realization of being alive, of life itself, they chose an image used for describing the act of reading these books: the image of the traveled road.⁷ Both metaphors—book and road—have the advantage of great simplicity and popular awareness, and the passage from the image to the idea (or, as my old schoolbook would say, from the vehicle to the tenor)⁸ can be smoothly and naturally effected. To live, then, is to travel through the book of the world, and to read, to make one’s way through a book, is to live, to travel through the world itself. An oral communication exists almost exclusively in the present of the listener; a written text occupies the full extension of the reader’s time. It extends visibly into the past of pages already read and into the future of those to come, much as we can see the road already traveled and intuit the one waiting before us, much as we know that a number of years lie behind us and (though there is no assurance of this) that a number of years lie ahead. Listening is largely a passive endeavor; reading is an active one, like traveling. Contrary to later perceptions of the act of reading that opposed it to that of acting in the world, in the Judeo-Christian tradition words read elicited action: “Write the vision,” says God to the prophet Habakkuk, “and make it plain upon tables, that he may run who readeth it.”⁹

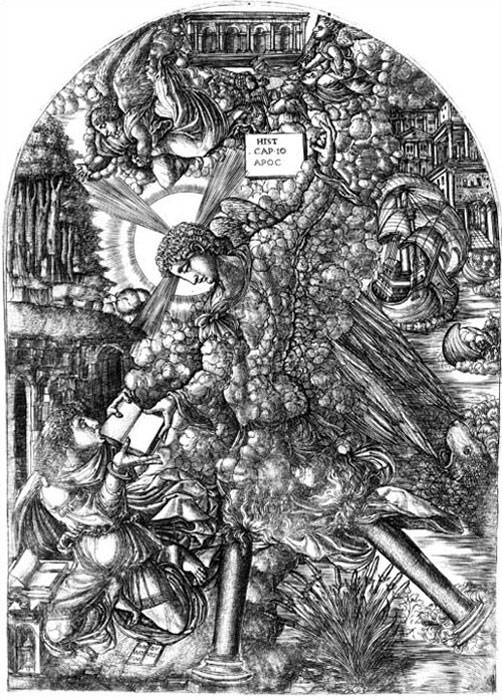

St. John devouring a book. Jean Duvet, The Apocalypse (1561).

© Trustees of the British Museum.

Composed probably a century after the prophecies of Habakkuk, the Book of Ezekiel offers an even clearer metaphor of the readable world. In a vision, Ezekiel sees the heavens open and a hand appear, holding a scroll of parchment that is then spread before him, “written within and without; and there was written therein lamentations, and mourning, and woe.”¹⁰ This scroll the prophet must eat so that he may speak the ingested words to the children of Israel. Much the same image is later taken up by Saint John on Patmos. In his Book of Revelation, an angel descends from Heaven with an open volume. “Take it and eat it up,” says the angel, “and it shall make thy belly bitter, but it shall be in thy mouth sweet as honey.”¹¹

Both Ezekiel and John’s images gave rise to an extensive library of biblical commentaries that, throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, see in this double book an image of God’s double creation, the Book of Scripture and the Book of Nature, both of which we are meant to read and in which we are written. Talmudic commentators associated the double book with the double tablets of the Torah. According to Midrash, the Torah that God gave Moses on Mount Sinai was both a written text and an oral commentary. During the day, when it was light, Moses read the text God had written on the tablets; in the darkness of the night he studied the commentary God had spoken when he created the world.¹² For the Talmudists, the Book of Nature is understood as God’s oral gloss on his own written text. Perhaps for this reason Philo de Biblos, in the second century, declared that the Egyptian god Thoth had invented simultaneously the art of writing and that of composing commentaries or glosses.¹³

For Saint Bonaventure, in the thirteenth century, Ezekiel’s book is both the word and the world. God, says Bonaventure, “created this perceptible world as a means of self-revelation so that, like a mirror of God or a divine footprint, it might lead man to love and praise his Creator. Accordingly, there are two books, one written within, and that is [inscribed by] God’s eternal Art and Wisdom; the other written without, and that is the perceptible world.”¹⁴ Faced with God’s double creation, we are entrusted with the role of readers, to follow God’s text and to interpret it to the best of our abilities. For Bonaventure, the constant temptation, the true demonic temptation, is expressed in the words of the serpent to Eve in the Garden: “Ye shall be as gods.”¹⁵ That is to say, instead of wishing to serve the Word of God as readers, we want to be like God himself, the author of our own book.¹⁶

Saint Augustine made this explicit in his Confessions, using his own childhood experience as example. How is it, he asks, that reading “the fancies dreamed up by poets” may entice us with what is untrue and steer us away from the truth of God? The craft of reading and writing “are by far the better study,” but they may lead us to believe in these “hollow fancies.”¹⁷ Human beings, according to Augustine, strictly “obey the rules of grammar which have been handed down to them, and yet ignore the eternal rules of everlasting salvation which they have received” from God himself. Our task therefore consists in balancing the experience of the pleasurable illusions created by the poets’ words, with the knowledge that they are illusions; to enjoy the translation into words of that which can be felt and known on this earth, and, at the same time, to distance ourselves from that knowledge and that feeling in order to read more clearly the contents of God’s word as written in his books. Augustine distinguishes between reading what is false and reading what is true. For Augustine, the experience of reading Virgil, for example, carries all the material problems that the reading of the sacred texts does, and one of the questions to be resolved is the degree of importance a reader is permitted to attach to either. “I was obliged to memorize the wanderings of a hero named Aeneas,” writes Augustine, “while in the meantime I failed to remember my own erratic ways. I learned to lament the death of Dido, who killed herself for love, while all the time, in the midst of these things, I was dying, separated from you, my God and my Life, and I shed no tears for my own plight.”¹⁸ The physical literary road taken by Aeneas becomes Augustine’s own mistaken metaphorical road of life, while the book in which he reads of it can be (but fails to be) a mirror of his own called-for regret.

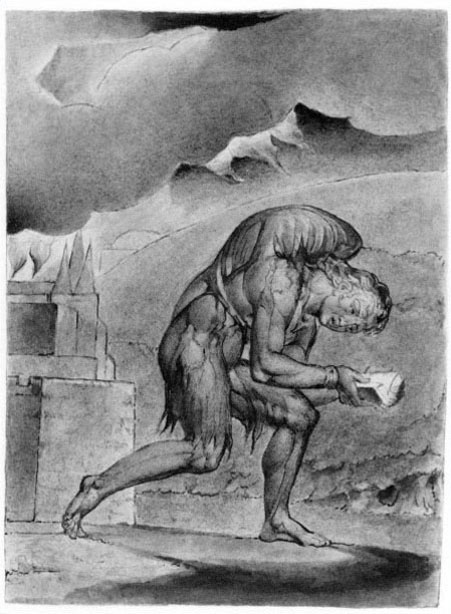

Reading the Bible has the same metaphorical function. “Between the paths of the Bible and those of its readers,” wrote the twentieth-century Israeli novelist Yehuda Amichai, “the words of Scripture are the space that must first be crossed: the first pilgrimage is that of reading.”¹⁹ The Bible is a book of roads and pilgrimages: the departure from Eden, Exodus, the travels of Abraham and of Jacob. In the penultimate chapter of the Pentateuch the last word is “to ascend,” that is to say, to travel on, toward the earthly Jerusalem or toward that other, celestial city. To walk, to wander, to saunter (from the Old French “Sainct’Terre,” the Holy Land)²⁰ is to make active use of the Bible’s words, just as to read is to travel. This analogy is made explicit in depictions of readers who turn the words on the page into worldly action, from Saint Anthony (who took the words in Matthew 19 literally and went out into the desert with nothing but the Gospel’s words)²¹ and the prophet Amos (who “reads” his own visions to the people of Israel)²² to Bunyan’s Pilgrim dreaming of a man “turned away from his own house, a book in his hand, and a great burden on his back.”²³ We advance through a text as we advance through the world, passing from the first page to the last through the unfolding landscape, sometimes starting in mid- chapter, sometimes not reaching the end. The intellectual experience of crossing the pages as we read becomes a physical experience, calling into action the entire body: hands turning the pages or fingers scrolling the text, legs lending support to the receptive body, eyes scanning for meaning, ears tuned to the sound of the words in our head. The pages to come promise a point of arrival, a glimmer on the horizon; the pages already read allow for the possibility of recollection. And in the present of the text we exist suspended in a constantly changing moment, an island of time shimmering between what we know of the text and what yet lies ahead. Every reader is an armchair Crusoe.

This becomes apparent in Augustine’s understanding of the relationship between the act of reading and the all- too-swift passing through life. “Suppose that I am going to recite a psalm I know,” he suggests in the Confessions.

Before I begin, my faculty of expectation is engaged by the whole of it. But once I have begun, as much of the psalm as I have removed from the province of my expectation and relegated to the past, now engages my memory, and the scope of the action which I am performing is divided between the two faculties of memory and expectation, the one looking back to the part which I have already recited, the other looking forward to the part which I have still to recite. But my faculty of attention is present all the while, and through it passes what was the future in the process of becoming the past. As the process continues, the province of memory is extended in proportion as that of expectation is reduced, until the whole of my expectation is absorbed. This happens when I have finished my recitation and it has passed into the province of memory.

William Blake, “Christian Reading in His Book.”

From Blake’s illustrations for John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (c. 1824).

For Augustine, the act of reading is a journey through the text being read, claiming for the province of memory the territory explored, while, in the process, the uncharted landscape ahead gradually diminishes and becomes familiar territory. “What is true of the whole psalm,” Augustine continues, “is also true of all its parts and of each syllable. It is true of any longer action in which I may be engaged and of which the recitation of the psalm may only be a small part. It is true of a man’s whole life, of which all his actions are parts. It is true of the whole history of humankind, of which each life is a part.”²⁴ The experience of reading and the experience of journeying through life mirror one another.