It is an uneasy lot at best, to be what we call highly taught and yet not to enjoy: to be present at this great spectacle of life and never to be liberated from a small hungry shivering self—never to be fully possessed by the glory we behold, never to have our consciousness rapturously transformed into the vividness of a thought, the ardor of a passion, the energy of an action, but always to be scholarly and uninspired, ambitious and timid, scrupulous and dim-sighted.

—George Eliot, Middlemarch

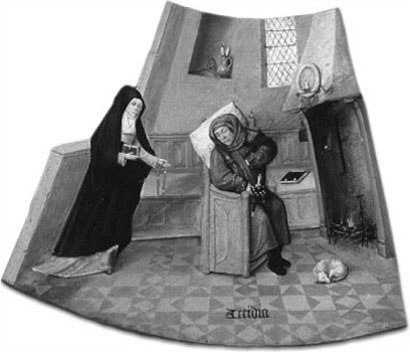

In front of a cosy fire, a curled-up dog at his feet, a man in a green dressing gown sits in his reading chair, but he isn’t reading. His book lies closed on an adjacent wooden chest. His head, wrapped in a pink scarf for warmth and comfort, leans against a white pillow. His right hand holds his robe, his left hand is tucked inside, as if to keep warm or to feel the beatings of his heart. His eyes are shut, so that he does not see (or does not choose to see) the nun approaching him with a prayer book and a rosary. The nun is perhaps an allegory of faith, summoning the man to his spiritual duties. A large side window shows a couple strolling through a bucolic landscape in the world of worldly pleasures. The shape of the picture is a sort of curved trapezoid and it lends the setting the appearance of a room in a tower. Stenciled on the patterned floor in Gothic letters is a single word: Accidia.

The image is part of a table top painted by Hieronymus Bosch in the first decades of the sixteenth century, and now in the Prado Museum in Madrid. The entire composition depicts, in a circle, the seven deadly sins, with a vigilant Christ in the center, rising over the warning: “Cave, cave, deus videt” (“Beware, beware, God sees”). Four medallions, one in each corner of the table top, illustrate, clockwise, the death of a sinner, the Last Judgment, the reception in Paradise, and the punishments in Hell. Our sleeper illustrates sloth, the sin known in the Middle Ages as that of the midday demon.

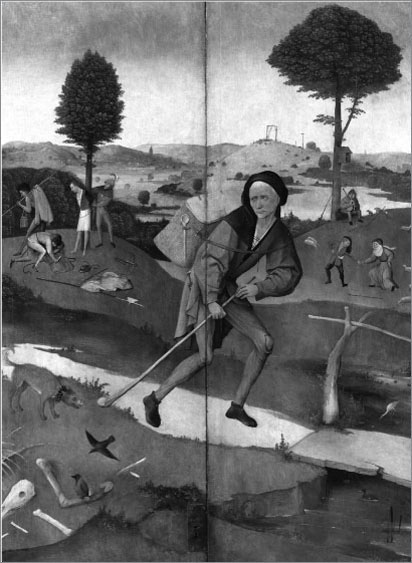

A second Bosch painting, known as The Peddler or The Prodigal Son, does not seem, at first instance, to deal with the same subject. The traditional titles of this work are misleading: the protagonist is less a peddler than a pilgrim, less one of the shady tramps of Flemish folklore than a man on a spiritual quest. The story of the Prodigal Son coming back to his father is perhaps a more fitting interpretation, since the allegorical reading speaks of the sinner repenting and returning to his Father in Heaven. Two versions exist of this work: one in the Boymans Museum in Rotterdam, another on one of the covering panels of the Hay-Wagon triptych in the Prado (a copy also hangs in El Escorial). In both versions, a middle-aged man advances through an everyday landscape of delights and threats. In the Boymans version, he is coming through a village; in the Prado version, he is out in the countryside, about to cross a stream. He is lean and shabbily dressed. One of his legs (an echo perhaps of the difference between “intellectual foot” and “affect foot,” mentioned in Chapter 1) is bandaged and slippered. He carries a basket on his back and a stick in his hands. He looks back toward a menacing dog wearing a spiked collar. In the background of the Boymans version is a tower, looming on the horizon above the pilgrim’s right shoulder. In the Prado painting, the tower is replaced by a gallows rising ominously on the hill above the pilgrim’s head. Gallows and tower share the same ignominious position.

Hieronymus Bosch, “Accidia.” Detail from The Table of the Seven Deadly Sins (c. 1485). Courtesy the Museo Nacional del Prado.

In the Middle Dutch translation of the bestselling Speculum Humanae Salvationis, it is stated that a pilgrim must leave his house and take to the road, and that he often has to seek back paths and defend himself against dangerous dogs with a stick.¹ Less an allegorical pilgrim than Everyman on the road to salvation, Bosch’s traveler responds to the late medieval Devotio Moderna movement in the Netherlands that called upon men to seek by themselves the road to salvation, trusting in God and guided not by what is set down in books but by their own reading of the world. In this, the pilgrim must be diligent: he must not allow himself to doze or tarry, or take in the words of false preachers, since “the Devil can quote Scripture for his own evil ends.” Instead, he must try to make out God’s true word in the text of the world, bearing in mind that, to prevent him from rightly following his path, the Devil has set temptations and menaces between the lines of the world’s page. One of the common dangers invented by the Devil was a fearful dog. According to Flemish folklore, this devil-dog haunted the roads; it could, however, be driven off with a walking stick, which rendered the creature powerless to pursue its victim across a stream, like the one in the Prado version.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Prodigal Son (1487–1516). Courtesy the Museo Nacional del Prado.

In the background of the Prado version, six of the seven deadly sins are represented: only the sin of sloth (accidia, more usually acedia) is not enacted. This role is left to the devil-dog. Only once the sinful effect is achieved (as in the acedia painting referred to first) can the devil-dog curl up and sleep. The Hortulus reginae of 1487 speaks of acedia as “similar to the bite of a rabid dog”; following its teachings, preachers warned their flocks that acedia is like the bite of a contagious dog, “a seminal vice that made one susceptible to all the others.”² An echo of this meaning can be heard in Winston Churchill’s reference to his acedia, depression, or melancholia as “a black dog.” Modern psychoanalytic parlance has retained the expression.

It is not easy to distinguish between states of “black dog,” acedia, depression, and melancholia; depending on the context, all can appear in a positive or a negative light.³ The ancient Greeks ascribed melancholia to the god Saturn and to one of the five bodily humors, black bile. According to legend, in the fifth century B.C.E. the philosopher Democritus, in order to escape from the follies and distractions of the world, set himself up in a hovel on the outskirts of Abdera in what appeared to be a state of melancholy. The citizens of Abdera, appalled by his conduct, asked Hippocrates to use his medical skills to cure the stranger, whom they took to be a madman. The wise Hippocrates, however, after examining Democritus, turned to the people and told them that it was they, not the philosopher, who were mad, and that they should all imitate his conduct and retire from the world to reflect in worthy solitude.⁴ Hippocrates took sides with the man who, bitten by acedia, retired to meditate on the world of which he wanted no part.

Early Christians understood that God is best encountered in isolation. Human intellect was a faculty given to us in order to assist us in our faith: not to clarify the unclarifiable mysteries but to construct a logical scaffolding to support them. The evidence of things unseen would not, by reflection and reasoning, render those things visible, but they would allow the thinker, the scholar, the reader (in the case of those who could read) to ruminate and build upon such evidence, granting the sinner-pilgrim clear sight to peruse the book of the world. For that reason, the isolation of religious men and women, in cells and caves and inhospitable deserts, assisted the work willed by God. Sometimes the isolation was accomplished high on a tower erected in inhospitable places, such as the one on which, in the fifth century, Simeon the Stylite, “despairing of escaping the world horizontally, tried to escape it vertically”⁵ and spent high above his brethren the last thirty-six years of his life.

But concomitant with this need for seclusion to nourish the inner life ran an undercurrent of guilt, a self-censuring of the very act of quiet thinking. Humankind, the church fathers taught, was meant to use its intellect to understand what could be understood, but there were questions that were not meant to be asked and limits of reasoning that were not meant to be transgressed. Dante charged Ulysses with a guilty curiosity and an arrogant desire to see the unknown world. Retreating into solitude with one’s own thoughts might allow for this same sinful desire to arise and, without the counsel and guidance of one’s spiritual leaders, remain dangerously unquenched. Therefore, the person seeking God in isolation was to concentrate solely on questions of Christian dogma and remain within the confines of dogmatic theology; pagan authors were dangerous because they distracted, like Ulysses’s sirens, from the true course.

In the fourth century, Saint Jerome recounted a dream in a letter to a friend. In order to follow his religious vocation and in compliance with the precepts of the church, Jerome had cut himself off from his family and renounced all earthly pleasures. What he could not bring himself to abandon was his library, which he had collected, “with great care and toil.” Wracked by guilt, he would mortify himself and fast, but “only that afterwards I might read Cicero.” A short time later, Jerome fell deathly ill. Fever caused him to dream, and he dreamed that his soul was suddenly caught and hauled before God’s judgment seat. A voice asked him who he was, and he replied: “I am a Christian.” “You lie,” said the voice, “you are a Ciceronian.” Overcome with dread, Jerome promised God that “if ever again I possess worldly books, or if ever again I read such, I have denied thee.”⁶ Jerome did not quite comply with his mighty oath, but the story is indicative of the dangers the church perceived in the reader’s tower.

Free to meditate on the miseries of the world, the solitary monk (the hermit, the anchorite, like the man in Bosch’s Accidia fragment) could be seduced into a state of suspended thought, melancholia, or, what was worse, the sin of acedia or sloth, the reverse of Ulysses’s sinful thirst for exploring, the shadow side of the philosopher’s reflective passion. In the ivory tower, the retired soul could lose himself or herself in inaction. Though melancholia, as has been extensively argued,⁷ is, in spite of its symptoms, a creative state, it is difficult to maintain a condition of concentrated meditation without falling into the acedic void. At such moments, the tower loses its nourishing power and becomes a place that drains spiritual and intellectual energy. At the beginning of Goethe’s Faust, the doctor laments that after reading philosophy and law and medicine, Faust feels himself incapable of accepting the tenets of the faith, and that he is none the wiser. The walls of his tower cramp his soul, and he believes that all his papers and instruments are nothing but “ancestral junk,” an image of the world invented by his thoughts. “I take no pleasure in anything now,” he says, “For I know I know nothing.”⁸ He could be voicing the lament for all his intellectual brethren.

The thinkers of the Renaissance tried to turn what the early Christians had seen as the sin of acedia into something like a virtue. The great humanist Marsilio Ficino, commenting on his own melancholia and his habit of withdrawing into solitude (“which only much playing of the lute can sweeten and soften a little”),⁹ attempted to withdraw himself from the influence of Saturn and ascribe his state to what Aristotle had called “a singular and divine gift,” and Plato before him “a divine furor.”¹⁰ Though warning scholars to avoid both phlegm (which blocks the intelligence) and black bile (which causes too much care) “as if they were sailing past Scylla and Charybdis,” Ficino concludes that thin black bile is beneficial for the man of letters. To encourage its flow, Ficino gives detailed instructions: not the energetic demeanor of the pilgrim, alert on the road, but the idling disposition of the philosopher, meditative and slow. “When you have got out of bed,” advises Ficino, “do not rush right in on your reading or meditation, but for at least half an hour go off and get cleaned up. Then diligently enter your meditation, which you should prolong for about an hour, depending on your strength. Then, put off a little whatever you are thinking about, and in the meantime comb your hair diligently and moderately with an ivory comb, drawing it forty times from the front to the neck. Then rub the neck with a rough cloth, returning only then back to meditating, for two hours or so, or at least for an hour of study.”¹¹ And Ficino concludes: “If you choose to live each day of your life in this way, the author of life himself will help you to stay longer with the human race and with him whose inspiration makes the whole world live.”¹² In certain cases and under certain conditions, as a source for philosophical enterprise, melancholy came to be seen as a privileged state, part of the intellectual condition, as well as the source of inspired creation, and the reader, locked away in his or her tower, as a maker in his or her own right.

The search for studious solitude led countless writers and artists, throughout the centuries, to imitate Democritus’s isolation. A seemingly endless span of brick-and-mortar towers crosses the literary landscape, from that of Rabelais in Ligugé to those of Hölderlin in Tübingen, Leopardi in Recanati, Jung at Bollingen. Perhaps more than any other, the tower in which Montaigne chose to set up his study has become emblematic of such refuges. Attached to the family chateau in the Bordeaux region, the four-story tower was transformed by Montaigne’s father from a defense building into a living space. The ground floor became a chapel, above which Montaigne set up a bedroom to which he could retire after reading in the library, which occupied the floor above, while a large bell rang the hours in the tower’s attic. The library was Montaigne’s favorite room, where his books, more than a thousand of them, sat on five curved shelves that hugged the circular wall. He tells us that from his windows he has “a view of my garden, my chickenrun, my backyard and most parts of my house. There I can turn over the leaves of this book or that, a bit at a time without order or design. Sometimes my mind wanders off, at others I walk to and fro, noting down and dictating these whims of mine.” Privacy was of the essence. “There,” Montaigne says, “I have my seat. I assay making my dominion over it absolutely pure, withdrawing this one corner from all intercourse, filial, conjugal and civic. Elsewhere I have but a verbal authority, one essentially impure. Wretched the man (to my taste) who has nowhere in his house where he can be by himself, pay court to himself in private and hide away!”¹³

Even today, the image of the ivory tower retains at times this connotation of allowing the intellectual to retire from the world only better to assume it. In 1966, the Austrian playwright and novelist Peter Handke gave a talk at Princeton entitled “I Am an Inhabitant of the Ivory Tower,” in which he opposed his own writing to the German literature that preceded him. “A certain normative conception of literature uses a lovely expression to designate those who refuse to go on telling stories, while seeking new methods to describe the world,” Handke said. “It says that they ‘live in an ivory tower’ and brands them as ‘formalists’ and ‘aesthetes.’” Handke started off his lecture by confessing: “For a long time, literature was for me the means, if not of seeing my inner self clearly, then at least of seeing with more clarity. It helped me to realize that I was there, that I was in the world. Certainly, I had become conscious of myself before dealing with literature, but it was only literature that showed me how this consciousness was not a unique case, not even a case, nor a sickness. Before literature, this self-consciousness had, so to speak, possessed me, it had been something terrible, shameful, obscene; this natural phenomenon seemed to me an intellectual deviance, an infamy, a motive for shame, because I seemed to be alone in this experience. It was only literature that caused my consciousness of this consciousness to be born; it showed me clearly that I was not a unique example, that others lived the same thing.”¹⁴ The intellectual act, performed in the ivory tower, is for Handke (as it has been for Ficino) a means of apprehending our own experience, and of putting the world into words.

Certain metaphors are slow in the making. Even though the image they depict has long been part of a society’s imaginaire, as an allegorical or symbolic figure, its metaphorical transformation, the actual wording of the image, can come much later. Death visualized as a territory into which we enter for the first time, without knowledge of its geography or of the path to take, appears in the earliest Sumerian texts and runs through almost every literature, until Shakespeare names it the “undiscovered country” from which no traveler returns. Sleep imagined as a stage of dramatic creation in which stories are acted out for the observance of the dreamer is frequently mentioned in the Epic of Gilgamesh, in early Egyptian literature, in the Anglo-Saxon poems and on into our time, but only in the sixteenth century does sleep become, in the words of Francisco de Quevedo, a “dramatic author” (“autor de representaciones”) who sets up his theater upon the wind. The reader seen as an eccentric withdrawn from the common affairs of society, aloof and supercilious, caring nothing for his fellow citizens, only for the world of books, is mocked in Greek and Roman satires, and turns up (alas) in every era, but it was not until the nineteenth century that the literal term “ivory tower” was used to denote the reader’s intellectual sanctum as a place of escape and alienation from the world.¹⁵ In 1837, the French critic Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve employed the term, perhaps for the first time, with no negative connotations, to contrast the abstract poetry of Alfred de Vigny with the more politically engaged lyrics of Victor Hugo, imagining the ivory tower as a bookish sanctuary, a place in which the intellectual could work quietly and effectively.

And Vigny, more secretly,

As if to his ivory tower, returned before noon.¹⁶

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the tower stands as a symbol of either protecting strength or perfect beauty. The Book of Proverbs says, “The name of the Lord is a strong tower: the righteous runneth into it, and is safe,”¹⁷ while Psalm 61 asserts, “For Thou hast been a shelter for me, and a strong tower from the enemy.”¹⁸ This image is mirrored in its reverse in the Book of Isaiah as the tower of the proud against which the Lord will victoriously rise.¹⁹ In the Song of Songs, the tower becomes a symbol of the beauty of the beloved (her neck is “a tower of beauty,” her breasts are “like towers”).²⁰ Sainte-Beuve’s image associated the notions of protection from the outside world and intellectual beauty that ideally make up the reader’s resilient, sensuous realm.

But soon afterward, the image of the tower as providing seclusion for studious intellectuals began to be used to depict not their haven but their hiding place, the cell to which they escaped from the duties of the world. In the public imagination, the ivory tower became a refuge set up in opposition to the life in the streets below, and the intellectual there ensconced was seen as a snob, an effete, a shirker, a misanthrope, an enemy of the people.

At the same time that the ivory tower acquired this denigrating connotation, another equally denigrating connotation arose: that of “the masses”—one entity redefining and sustaining the other in a mutual battle of execration. Already in the first century, Seneca, taking sides with the ivory tower intellectual, railed against the ignorant populace or masses. “The best should be preferred most,” he wrote, “and yet the masses choose the worst....Nothing is as noxious as listening to the masses, considering as right that which is approved by most, and modelling one’s behaviour on those who live, not according to reason, but merely to conform.”²¹ Implied in the condemnation is the notion that the individual life of the mind should be preferred to the communal rule.

In his important book on intellectuals and the masses, John Carey observes that the varying concepts of “masses” in Hitler’s Mein Kampf (“as exterminable subhumans, as an inhibited bourgeois herd, as noble workers, as a peasant pastoral”) would be familiar to contemporary readers. “The tragedy of mein Kampf,” Carey writes, “is that it was not, in many respects, a deviant work but one firmly rooted in European intellectual orthodoxy.”²² The perceived opposition between the thinking, creative elite and the pusillanimous, uncomprehending masses has a long tradition in Europe. Carey begins his history with Ortega y Gasset’s Revolt of the Masses of 1930, where the Spanish historian notes that while up to 1800 the population of Europe did not exceed 180 million, from then to 1914 it grew to 460 million human beings. Faced with this “flood,” “swarm,” “inundation,” “explosion” (these are a few of the terms used by writers at the time), the individual intellectual felt threatened and saw the very existence of these “masses” as an abomination. At the same time that movements of democratization were advancing in many different social areas, intellectuals were seen to be retreating further and further into their ivory towers, far from what the novelist George Moore called “the blind, inchoate, insatiate Mass.”²³ To the tower of the melancholy intellectual, modern imagery opposed the open spaces of the crowds. Toward the former, there developed a certain feeling of resentful claustrophobia, while a feeling akin to a haughty agoraphobia arose toward the faceless masses.