Here Doctor, cry’d she, pray sprinkle every Creek and

Corner of this Room, lest there should lurk in it some

one of the many Sorcerers these Books swarm with,

who might chance to bewitch us.

—Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote, 1:6

Like the Venetian lion caught between the prestige of intellectual power and mockery at the inefficiency of words, the reader became trapped in a double bind. The book lover became the Book Fool, and the devourer of books became the bookworm, both parodies of the enraptured reader. “In short, he became so immersed in his books that he spent the night reading from dusk to dawn, and the days from dawn to dusk, until at last, from little sleeping and much reading, his brain dried up, and he came to lose his wits.” This is how, in 1605, Cervantes defined the Book Fool we know as Don Quixote. And yet, when Cervantes portrayed his brave knight, he was not quite defining the reader rendered mad by his books. Rather, Cervantes was defining a society madly afraid of its own untruths. No doubt, as we are told in the opening chapter, Alonso Quijano believes in the factual reality of the stories he reads. But then, throughout the novel, it becomes clear that Don Quixote’s conception of the world is something more complex than mere delusion. On several occasions, on the verge of allowing himself to be swept away by the fantasy concocted from his readings, Don Quixote negotiates the chasm between what is real in the world and what is real to his imagination, with lucid intuition. Many times he allows the fantasy to overwhelm him, as in the famous scene of the windmills, and suffers the consequences with his battered bones. But at other times he enters the fantasy consciously, like a reader who knows that the story is fiction and yet believes in its revealed truth, as when Don Quixote forbids Sancho to peep under the blindfold and see whether or not the wooden horse is truly carrying them through the skies; or when the enamored knight refuses to show the muleteers a portrait of Dulcinea as proof that she is the most beautiful woman on earth, “for what good would it be to swear, if you need proof in reality.”

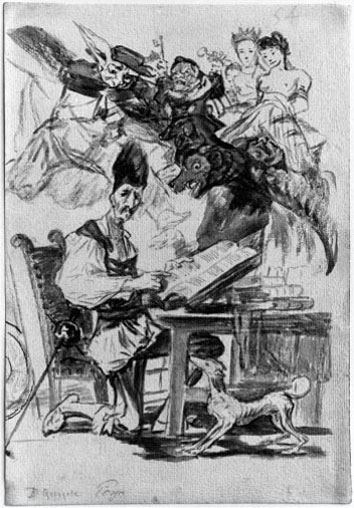

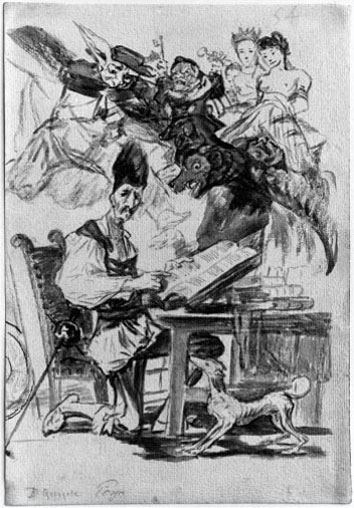

Francisco Goya, “Don Quixote” (c. 1812–1820). British Museum, London.

Courtesy Alinari / Art Resource, NY.

In counterpoint, neither is the hold of the “real” world all that strong on those who deem the knight to be mad. The curate and the barber, who cull Don Quixote’s library in order to rid it of “pernicious” titles, preserve however from the flames a fair number of volumes that they believe to be important (for themselves) both as entertainment and as means of knowledge. The innkeeper who holds public readings of novels of chivalry tells how for each of his listeners—reapers, farmhands, prostitutes, youngsters—the story acquires a personal meaning and gives a private delight, helping them bear the hardships and sorrows of daily life. And the aristocrats who make fun of the poor old knight and play cruel jokes on him live in a world in which they transform their fantasies into realities and their whims into a parody of justice. This play between the explicit imaginary world of the protagonist and the unconscious world of those around him places the reader of Don Quixote uncertainly between both, as one of the solitary creatures who find in books the experience of reality, and also as a member of the society that derides reading and wishes to impose its own views of what is and is not collectively worthy.

In Plato’s seventh (and perhaps apocryphal) letter, the philosopher states that there are certain truths that cannot be put into writing. And even if they can be written of, they cannot not be learned by merely perusing the page: they must be discovered by the readers themselves after much toil and experience, when suddenly the knowledge springs like a spark into the soul, allowing it to feed itself.¹⁶ This argument, repeated over the centuries, suggests that reading cannot teach us the truest, deepest things, and that to pretend to supplant life with reading is folly.

And yet, putting into writing words that describe experience has a prestige far greater than that of intuitive learning. In the early fourteenth century, Rabbi Sem Tob de Carrión, in his Moral Proverbs, noted what was by then a commonplace:

The word pronounced / is by and by forgotten,

But writing remains / for ever preserved.

And the arguments not / set down in writing,

Are like arrows / that will not reach their goal.¹⁷

In spite of Plato’s warning, writing (and therefore reading) became a means of instruction and knowledge. Even if the reader knew that the stories were made up and the characters only lived in the imagination of their author, this stuff made of dreams acted upon the minds of readers as models of the world in which we still attempt to survive.

“As manifest experience shows, the weakness of memory, consigning to oblivion not only those deeds made old by time but also the fresh events of our own era, has made it appropriate, useful, and expedient to record in writing the feats of strong and courageous men of old. Such men are the brightest of mirrors, examples and sources of righteous instruction, as we are told by the noble orator Tully.”¹⁸ Thus begins Tirant lo Blanc, the novel of chivalry that the barber and the priest, intent on burning Don Quixote’s library, decide to save from the bonfire as “the best book of its kind in the world.”¹⁹ Even within a story that appears to condemn the reading of such books as folly, it is stated that certain of these books lead us to the contrary of folly, and grant us “mirrors, examples and sources” of ancient righteousness and illustrious behavior.