Universally acknowledged as one of the most influential masterpieces of silent cinema, F. W. Murnau’s 1922 expressionist classic, Nosferatu, still haunts viewers today, still exerts an uncanny power. It was ground-breaking in so many ways, not least because it was not studio-bound, being shot almost entirely on location… If, like me, you are a horror movie buff and love this film, then it’s hugely exciting to anticipate being there—visiting the actual filming locations of one of your favourite movies. And for Nosferatu, all the information is well documented, allowing us to put together an itinerary to visit those iconic locations in Germany and Slovakia where it was principally filmed.

To put all this in context: I did not do this alone. Members of the Dracula Society (of which I am currently Chair and Treasurer) love to travel. One of the Society’s founding objectives back in 1973 was to visit Dracula’s homeland, Transylvania, at a time when tourism to Romania barely existed. Since then, we’ve travelled to Egypt (mummies), Prague (the Golem) and Paris (The Phantom of the Opera) in search of authentic locations. But our reverence for Nosferatu has taken us to Slovakia no less than three times (2001, 2011 and 2022), and to Germany twice (2012 and 2019).

Let us return, then, to Murnau’s masterpiece Nosferatu, and we’ll begin with Thomas Hutter and his wife Ellen, at their home in the fictional German town of Wisborg, which we visited in 2019. This is, in fact, Wismar, a gorgeous Hanseatic port city on the Baltic coast. The opening shot of Murnau’s film is taken from the tower of the Marienkirche (St. Mary’s Church), looking down at the market square with the Wasserkunst (an elaborate wrought-iron fountain) clearly visible on the left. Sadly, the hexagonal spire that we see in the foreground of the shot no longer exists, the rest of the church having been destroyed in a bombing raid in April 1945. The Markt with its fountain appears now much as it did in 1921 when Murnau was filming there.

The first and most obvious location we identified was the Wassertor, the harbour gate of Wisborg, through which Graf Orlok carries his coffin into the city in that wonderful blue-tinted scene. You don’t see the top, crenelated gabled part above the gate in the actual film, but it’s an impressive structure. And of course, who can forget that ominous shot in the film where Orlok’s death ship, the Empusa, slowly glides into harbour from the right of the frame, presaging the disaster to come?

It’s was pleasing to see that Wismar is aware of its Nosferatu film connections, with helpful plaques set in the ground at important locations around the city to remind tourists of the fact. There was one by the Wassertor, and another in the courtyard of the Heiligen-Geist-Kirche (the hospital Church of the Holy Spirit), the other main location here used in the film. This courtyard is where ship-owner Harding lived, and where Ellen stayed to be looked after by his wife Ruth, when Hutter departed on horseback on his fateful journey to Transylvania. The courtyard looked pretty much as it does in the film, although on our visit there was some building work going on, with an area cordoned off by red and white tape.

While the exterior shots of ship-owner Harding’s house in Wisborg were actually filmed in Wismar, we had to travel to Lübeck, another German city on the Baltic coast, to seek out four other important filming locations. The first was Count Orlok’s new residence, which was virtually impossible to miss: you just pass through the western city gate (the Holstentor), stroll along the Upper Trave River, and there they are— six tall, historic salt storehouses (Salzspeicher), two of which are gabled and are instantly recognisable from their rows of small black windows. Comparing the window configuration with a screen grab from the film, we were even able to pinpoint the actual window Graf Orlok stares out from.

With the aid of google maps and more screen grabs, we went in search of the other locations. Hutter’s house was easily identifiable in a small square near the churchyard of St. Aegidien, just a short way off a street called Depenau, which we recognised from the scene in which coffin bearers carrying plague victims make their slow procession. Many of these streets were used in the scenes where the townspeople are on the hunt for Knock. The final Lübeck location we tracked down was from an early scene in which Hutter encounters Professor Bulwer: this was the medieval Fuchting’s Courtyard off Glockengassen Strasse, looking just as calm and peaceful as it did in 1921.

That was most of the Germany film locations ticked off, but what about Transylvania? Murnau didn’t actually take his film crew to “the land beyond the forest”. He went to Slovakia instead. Hutter’s journey through the mountains and valleys was filmed in the High Tatras and the Vratna Valley in northern Slovakia. And his destination, Count Orlok’s castle, is Oravsky Hrad—the magnificent Orava Castle—perched high on a rock overlooking the Orava River. Probably still my favourite of all the castles I’ve ever visited, Orava never fails to impress. (Mark Gatiss obviously thought so too, as he went there to film it as the location for Dracula’s castle in his BBC TV adaptation of Stoker’s novel in 2020).

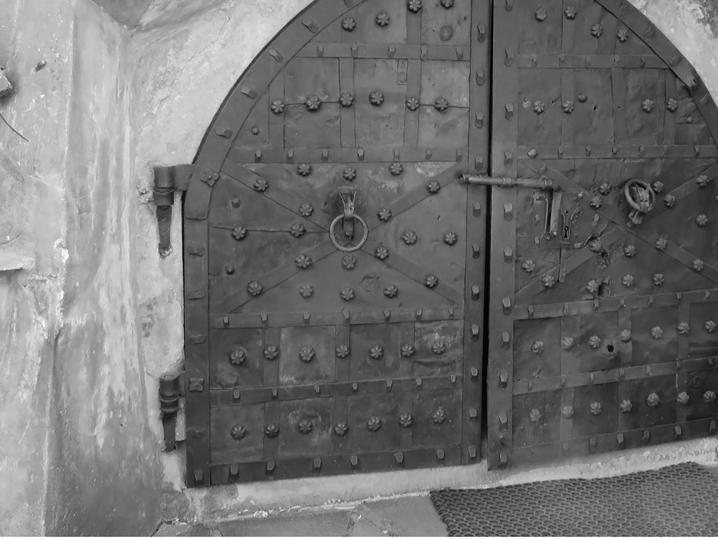

Our first visit to Orava was in 2001, when the experience felt arguably the most authentic. Our guide had to phone the keyholder to come and let us into the castle, so there were no tourists, just us. Everywhere we looked brought back a scene from the movie: the approach to that great arched door where Orlok welcomes Hutter to his home, the inner courtyard and the circular tower with its dark, pointed roof, and the small domed structure by a balustrade where Hutter writes his letters to Ellen. There were no restrictions in 2001. In 2011, this area was roped off, but our guide did manage to gain us admission. Not so in 2022—a padlocked gate barred all access. But that is how progress works: Orava castle now attracts hordes of tourists, with timed admission for its two-hour tour, and souvenir stalls, cafes and restaurants have mushroomed up all around. But on the plus side, Murnau’s landmark movie is now publicised everywhere: a large banner at the castle entrance referenced Nosferatu’s centenary in 2022, there’s an exhibition devoted to it in the citadel on the highest level, and on our visit, even a display of Count Orlok artwork—all by school children!

Still in Slovakia, some sixty-odd kilometres from Orava, is one other location in the film that we finally managed to tick off our list, on our 2022 trip. You know the one? The shot of Orlok’s ruined castle at the very end of the film. This has long been established as the ruins of Starý Hrad (“Old Castle”), which towers high above the Vah River. Probably, most people would content themselves with just viewing the ruins from the road below, just as you see them in that final shot. But not our little group—we just had to climb the steep path up through the forest to clamber over the actual castle. But just as we emerged at the summit, everything got strangely surreal… There before us was a unit of Wehrmacht soldiers, encamped around the castle ruins. Had we suddenly passed through a time warp? Or been transported into a real-life version of The Keep? Alas, no—just a group of WW2 re-enactors preparing to recreate a major battle the next day. (We encountered several groups of partisans on the way back down). An experience at a Nosferatu castle evoking another, very different, vampire movie… Not particularly relevant to my reminiscences of visiting the 1922 Nosferatu sites perhaps, but—all part of the adventure.

And finally, we come to a couple of locations that are appropriate to mention here—particularly at the end of these recollections. Back in Germany, to the south-west of Berlin, are two cemeteries. The Wilmersdorfer Waldfriedhof, in the Berlin suburb of Stahnsdorf, is a large forest cemetery, and with the help of a German speaking fellow-Dracula Society member, we managed to locate the grave of Max Schreck. Neglected for many years, a new granite slab was erected in 2011, bearing the simple words “Max Schreck, Schauspieler” (Actor), with the dates of his birth and death. F. W. Murnau’s grave, by contrast, has a much more imposing resting place, as you might expect, and this can be easily located in the nearby, quite separate, cemetery of Sudwestkirchhof.

Murnau died in a car accident in California in 1931, but in classic Dracula style his body was shipped to Berlin for interment. There he lay undisturbed until July 2015 when his grave was broken into and his skull stolen. Wax candle residue found at the scene suggests some sort of occult ceremony may have taken place and the whereabouts of his skull is unknown to this day.

At both graves, Dracula Society members raised a toast to the memory of two men who helped create one of the most powerful and influential horror films of all time.

Plates:

Although now tourist attractions, various sites in F. W. Murnau’s silent masterpiece Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror have been preserved and remain largely unchanged:

1. Courtyard inside Orava Castle—In the original movie, Hutter walks towards the camera in this scene.

2. Wismar (“Wisborg” in the film—the harbour gate through which Orlok is seen carrying his coffins.

3. Lübeck—the restored Salzpeicher (salt storehouses) used by Murnau as Orlok’s “new” residence.

4. Inside Orava castle—the heavy double doors leading down to Orlok’s crypt.

1. Courtyard inside Orava Castle - Hutter walks towards the camera in a similar shot

2. Wismar (‘Wisborg’ in the film) - the harbour gate through which Orlok is

seen carrying his coffins

3. Lübeck - the restored Salzpeicher (salt storehouses) used by

Murnau as Orlok’s “new” residence

4. Inside Orava castle - the heavy double doors leading down to Orlok’s crypt