My Two Oscars

On Wit and Melancholy

Rosalind: They say you are a melancholy fellow.

Jacques: I am so; I do love it better than laughing.

—As You Like It

Underneath this flabby exterior is an enormous lack of character.

—Oscar Levant, An American in Paris

Oscar Levant is a melancholy figure, full of barbed wit, self-loathing, and “Rhapsody in Blue,” which he performed more than any other twentieth-century pianist. You may not know who he is, though Jack Paar used to go off the air after a time saying, “Goodnight Oscar Levant, wherever you are.” Jimmy Durante used to say, “Goodnight Mrs. Calabash, wherever you are,” and no one ever knew who she was, which he must have found disconcerting.

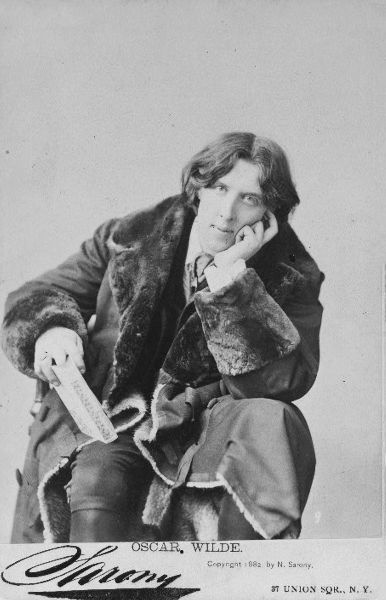

Oscar Wilde, you undoubtedly know, but you may think of him staring languidly into the camera, dressed as a dandy, self-pleased.

4. Oscar Wilde. New York Public Library Digital Collections, Billy Rose Theatre Collection.

5. Oscar Levant. © age fotostock.

I think of my two Oscars as trying to say the perfectly witty thing as a way of staying the melancholy that dare not speak its name. I think of wit as a stay against melancholy, a brief moment of verbal perfection, before its self-immolation: time.

Our attitude toward wit is: what have you said for me lately? Wits, whether Dorothy Parker or Oscar Levant (friends, by the way), or Oscar Wilde, or Samuel Johnson, make their own traps that wit springs them out of: expectation. The only way a wit can stop being a wit is to be dull, a melancholy resolution.

Oscar Levant looked a bit like a cross between Leslie Caron and Delmore Schwartz on a bad day, except for his long fingers, which must have played “Rhapsody in Blue” a thousand times. If you don’t know who Leslie Caron and Delmore Schwartz are, let’s say Levant looked like a moon for the misbegotten, with bad teeth. So, early in the essay I keep asking if you know who people are—that really means I’m concerned about my age, and yours, about whether this is a December-May essay, which might be a melancholy affair.

Like Leslie Caron, with whom he starred in An American in Paris, when he was known as one of the wittiest men in America, Levant had moony eyes. This was before he spiraled into multiple psychiatric commitments, addiction, and electric shock therapy. He would emerge one of the wittiest broken men in America, and the first full-fledged American performative psychodrama: he prefigured reality TV and the performance comedy of the neurotic self in actor comedians like Woody Allen, Larry David, and Louis C.K. “What do you do for exercise?” Jack Paar asked him in 1959. “I stumble and fall into a coma,” Levant said. That, of course, would relieve him of his wits (the Old English gewitt, the base of consciousness). If melancholy, not brevity, is the soul of wit, perhaps it is because sadness is our natural fallen state. Awareness is a painful condition: moony, misbegotten, sublunary—except when Oscar played the piano.

Melancholia, you may already know, derives from the Greek (which seems rather perfect to me; one person’s epic hero is another’s sad, anxious wanderer, or monomaniacal and impulsive oppositional type with authority problems) melaina chole, translated into Latin as astra billis and English as the black bile, an excess of which caused, and perhaps still causes for all we know, chronic sadness, which is, according to Hippocrates, in the fifth century BCE, one of the four humors, or temperaments, along with the Sanguine, the Choleric, and the Phlegmatic.

Aristotle, as far as we know, wrote the first essay on melancholy, at the least, the first that survives. And the temperaments are still being tossed around in the twentieth and twenty-first century: Balanchine and Hindemith collaborated on The Four Temperaments, Carl Nielsen composed a symphony called the Four Temperaments, the Waldorf schools rely on a version of them in their pedagogical ideology (so if you have melancholy children, relax, you know where to enroll them), and so on. Seneca, in De tranquillitate animi, notes the difficulty of pinning down melancholy, or violent sadness, in name or cause. Burton, temperamentally rather different than Seneca, eases melancholy by musing over just this difficulty for hundreds of pages, to our delight.

The Hippocratic, or Temperamental school of thought, merged or married with the Latin in the form of Galen in the second century, and melancholy began its slow dance between this condition as problem and irremediable burden, or mark of specialness, even genius, as the melancholic looks inward, acts different, perhaps even performs a Saint Vitus dance of the self, and is possessed of some inordinate talent. In his journals, published as Straw for the Fire, Theodore Roethke writes, “Sure I’m crazy. But it ain’t easy.” In Anatomy of Melancholy, Burton writes, “Why melancholy men are witty, which Aristotle hath long since maintained in his Problems, and that all learned men, famous philosophers, and lawgivers, ad unum fere omnes melancholici, have still been melancholy, is a problem much controverted.” Burton also refers to the Aristotelian or pseudo-Aristotle Problema of the fourth century BCE—so the idea had melancholy legs.

As Clark Lawlor notes, in From Melancholia to Prozac, “The Renaissance saw the rise of the first form of melancholy in a flourishing of the myth of melancholic genius that has persisted up to the present day” (42). Marsilio Ficino, the fifteenth-century philosopher priest, aided the union of melancholy and genius, sprinkling the discourse of love and alchemy, and finding that, in fact, every man of genius was melancholic, though the humoral conception of the body maintains, as we see in Montaigne.

In his Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man (1795), Schiller avers that we all share in the condition of melancholia. Perhaps that’s the real beginning of the history of “depression.” Attention must be paid when melancholy separates from genius and becomes ordinary.

In the nineteenth century, melancholy becomes pharmaceutical, at least in a more organized way with the spreading use of opium, laudanum, which had been around since Thomas Sydenham, “the English Hippocrates,” concocted it in the seventeenth century. His recipe: opium, two ounces; saffron, one ounce; bruised cinnamon and bruised cloves, each one drachm; sherry wine, one pint. Mix and macerate for fifteen days and filter. Twenty drops are equal to one grain of opium. The results, as we know, thrilling and disastrous.

Not every melancholic is a genius. But Oscar Levant, along with his namesake Oscar Wilde, was a self-made genius, at least a self-proclaimed one, which alternated with a deep vein of self-laceration, a running theme of his witticisms. At the beginning of An American in Paris, Levant, who wrote almost all the lines for the films he was in, announces, “I’m the world’s oldest child prodigy.” Self-pity and delusions of grandeur—a classic combination! Except that Levant was an excellent concert pianist.

I’m not sure if any of us quite know what a genius is. But Levant did: it was George Gershwin, and he measured himself against Gershwin disastrously.

How melancholy to become the memorialist for the man you loved (“The Man I Love”?) and against whom you measured yourself so severely.

All of Levant’s film performances, from Romance on the High Seas to Humoresque to The Barkleys of Broadway to An American in Paris, are variations on the theme of Oscar Levant, the amanuensis of love, the musical third wheel. Oscar is always there to help speed or console the romantic action. But along the way, he gives us bracing asides; he’ll tell us that “my psychiatrist once said to me, ‘Maybe life isn’t for everyone.’” He’s the tonic to the saccharine action.

Oscar Levant said, repeatedly, “There is a fine line between genius and insanity. I have erased that line.” It reminds me of the line in Montaigne’s “Of Cripples”: “I have seen no more evident monstrosity and miracle in the world than myself.” If there is a kind of theory of melancholy in Montaigne’s essays, a melancholy apologia, it’s in “Of Democritus and Heraclitus.” He writes:

Democritus and Heraclitus were two philosophers, of whom the first, finding the condition of man vain and ridiculous, never went out in public but with a mocking and laughing face; whereas Heraclitus, having pity and compassion on this same condition of ours, wore a face perpetually sad, and eyes filled with tears. I prefer the first humor; not because it is pleasanter to laugh than to weep, but because it is more disdainful, and condemns us more than the other; and it seems to me that we can never be despised as much as we deserve. Pity and commiseration are mingled with some esteem for the thing we pity; the things we laugh at we consider worthless. I do not think there is as much unhappiness in us as vanity, nor as much malice as stupidity. We are not so full of evil as of inanity; we are not as wretched as we are worthless.

Oscar Levant veers between Democritian and Heraclitian melancholy, tending toward the former. Consider: “There used to be an act in the old Club Eighteen in New York where a temporarily unemployed actor would step into a green spotlight in the middle of the floor and commence to recite Longfellow’s poem which begins: ‘I shot an arrow into the air. It fell to earth I knew not where.’ The reciter would pause, then sadly say: ‘I lose more damned arrows that way.’ That has been my history of manufacturing jocose remarks” (The Unimportance of Being Oscar, 15).

Oscar Levant told this story obsessively: George Gershwin and Levant were taking the train together, spending the night in the Pullman, and Gershwin swung into the lower bunk. As Levant was climbing into the top bunk, Gershwin said, “You see Oscar, that’s the difference between genius and talent. Lower bunk, top bunk.” Ironically, in Rhapsody in Blue, Levant himself speaks the line, making the distinction. Is this deference to Gershwin, or self-slight, post-mortem? It isn’t completely clear if the two friends had been playfully sparring, or if Gershwin was sadistically poking Levant. He seemed to like to keep Levant in his place, to let him know who the real genius was. After asking Levant to perform with him at Lewisohn Stadium, Gershwin asked Levant if he wanted to be paid or have a watch that Gershwin had inscribed for him: “To Oscar, from George.” For the next thirty-five years Levant never performed without wearing it.

Levant met Gershwin when both were reasonably young, but Gershwin was already being touted as the next big thing and would become it. Levant would become a hanger-on, a Gershwin interpreter, interloper, intimate—apparently anything with an i, as long as it didn’t distract from Gershwin’s ego. Levant became so associated with “Rhapsody in Blue” that there are references to it in all his films. Those are Levant’s hands playing the piano for Robert Alda in the piano sequences in the Gershwin biopic Rhapsody in Blue, and Levant plays “Rhapsody in Blue” in its entirety in the film.

Having established himself as the sidekick to Gershwin, Oscar Levant played a sidekick in his films. But he was a different take on the sidekick—isolate, never fawning, the self-possessed neurotic, if that isn’t a contradiction in terms. You keep expecting Levant to break the fourth wall, the way Groucho does in the Marx Brothers movies. In Rhythm on the River, with Bing Crosby and Mary Martin, Levant is lounging, reading his own memoir, A Smattering of Ignorance. “A very irritating book,” he comments before putting it down. Frequently, Oscar Levant mutters something brilliant out of range of anyone but us, which establishes, with fierce economy, our relationship with him and the very nature of most wit: it’s actually unheard. “I find that girl completely resistible,” he says to himself in The Barkleys of Broadway. In Humoresque, he mutters, “I envy people who drink. At least they know what to blame everything on.”

An American in Paris (1951) may be Oscar Levant’s most well-known film role, partly because it’s his most well-known film, even a notch more than The Band Wagon (1953), a much better film. The two films are separated by two years, two dancers, and a heart attack—Oscar’s. The dancers are Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire. I must admit a prejudice against An American in Paris, the second Gershwin-inspired film Levant is featured in. Here it is: Despite being an avowed Fred Astaire acolyte, I’ve liked Gene Kelly pretty well in most of his major films. But not here. His character, Jerry Mulligan (named after Gerry Mulligan? The saxophone player that moved to Los Angeles after leaving Miles Davis’s band) is a struggling artist who is taken up by the beautiful and sexually available socialite Milo Roberts, played by Nina Foch. Because of his fear of being sexually and financially castrated by Milo, Jerry ends up repeatedly sexually humiliating her in his pursuit of the gamin Lise Bouvier, played by Leslie Caron. (Levant looked like Caron in a funhouse mirror, like her father once removed by disaster.) Gene Kelly’s Jerry Mulligan paintings are awful, warmed-over street corner impressionism, and his character superficial, casually cruel, and narcissistic. So here’s this nice looking wannabe artist, whom this enchanting woman does everything for (sure, he dances reasonably well, a nice smile), but I think Nina Foch is enchanting: supportive, witty, abandoned. Is there a specific neurosis to our objection to the fates of characters central to the rhythm of films of novels, whose disposition we find objectionable? My Nina Foch objection (which I’ll talk about again later, like any good obsession), which I experience like righteous indignation, has been my central pleasure in watching the film, a film I don’t love. It’s an experience of neurotic movie watching that Levant would probably appreciate. In the film, Foch’s original sin is that she’s older and richer than Gene Kelly. Yes, “I Got Rhythm” is a charming number, but the film leaves a bad taste in my mouth. Structurally, there is a strange moment at the very beginning where we’re almost offered a narrative alternative. We see the life of Jerry Mulligan, struggling artist, genius manqué. And then we’re presented with Adam Cook, Oscar Levant, the nascent concert pianist, the real artist. But we don’t ultimately get parallel narratives, which would be the interesting film that we don’t get to go back and shoot. Oscar is the narrative not taken. We see Cook’s talent whenever Levant sits at the piano.

He’s playing Gershwin, of course.

Oscar Levant tries to mediate his two friends’ interest in the same woman in the film, but it just makes him a nervous wreck: the wreck of the Levant, which sounds like a great disaster. It was, eventually. However, in one of the most fully realized sequences of Levant’s film career, he fantasizes playing Gershwin’s “Concerto in F,” and conducting, and playing the violin, and being in the audience—simultaneously. It’s a sly and funny commentary, dreamed up by Levant, who pitched it to Vincente Minnelli, about ambition, artistic ego, self-congratulation, and at the end of the fantasia Levant is back in melancholy real time, shaking his head as though to say, “Well, yeah, in my dreams”—the real work of the performing artist.

Oscar Levant provides us with an alternative, if undeveloped, possibility of character in the film: he doesn’t care about money at all. He may fantasize, but he doesn’t sell out or throw anyone under an emotional bus. “The supreme vice is shallowness,” as Wilde writes in De Profundis. Levant is our alternative to Kelly’s shallowness in American in Paris.

“I’m a concert pianist,” he says. “That’s a pretentious way of saying I’m unemployed at the moment.”

The melancholy of wit is frequently accompanied by unrequited love, the wit turned inward as if saying this is what I should have expected, or what I deserve. Dorothy Parker’s “I am Marie of Romania” and her line about an early abortion: “That’s what I get for putting all my eggs in one bastard.” Levant was enthralled with Gershwin, call it what you will.

Oscar Levant was completely aware of his namesake, the other Oscar, Wilde, whose unrequited love is the occasion of his most melancholy, penultimate work, De Profundis. Levant calls his ultimate memoir The Unimportance of Being Oscar. In the 1955 film The Cobweb, Levant, severely diminished by having been a mental patient so often the last several years, is undergoing hydrotherapy. A nurse stops in to tell him it’s time for bed. Levant, who wrote almost all of his own lines, says, “That’s the wittiest thing anyone has said since Oscar Wilde.” And in The Unimportance of Being Oscar, Levant writes, “The two great writers who have never let me down over years are Samuel Johnson and Oscar Wilde” (174).

In “The Critic as Artist” (1888) Oscar Wilde writes, “What people call insincerity is simply a method by which we can multiply our personalities.” He also says, in self-enshrinement, “It is much more difficult to talk about a thing than to do it.” There is a melancholy vein in Wilde—in this essay as elsewhere—that fully emerges only after his fall in De Profundis. But even earlier, when he speaks of music in “The Critic as Artist,” Wilde writes, “After playing Chopin, I feel as if I had been weeping over sins that I had never committed, and mourning over tragedies that were not my own.”

Reading De Profundis is always a profoundly moving and strange experience. It’s one of the most wrenching works of epistolary literature. Wilde can’t seem to break free of Alfred Douglas, Bosie as he calls him, despite compiling a rogue’s gallery of offenses that Bosie has committed against him, really nasty stuff, like when he left Wilde alone in his rooms in Paris when he was dreadfully ill, despite Wilde’s having cared for Bosie during his illness. The line that Wilde can’t shake is Bosie having said to him, “When you are not on your pedestal, you are not interesting.” When Wilde was ill, he was not on his pedestal, not interesting, but there for Bosie to tap into for cash. Wilde’s refrain in De Profundis is, “The supreme vice is shallowness.” He repeats it like an accusation, but it’s a self-haunting line. Nothing is shallower than the flat surface of a mirror.

In “Mourning and Melancholia” Freud distinguishes between the conscious grief one feels at the loss of a loved one through death, and the loss of a beloved object we have desired and identified with, which puts us in an unconscious state of grieving, of melancholia. Freud stresses that the melancholic has “a loss in regard to his ego.” He goes on to explain the nature of the loss, the transformation, the internalizing of the other: “The shadow of the object fell upon the ego, and the latter could henceforth be judged by a special agency, as though it were an object, the forsaken object. In this way an object-loss was transformed into an ego-loss.” The melancholic in this vision has become the thing he has lost, and he continually loses himself. For this to happen, “a strong fixation to the loved object must have been present.” I think of Oscar Levant’s melancholy devotion to George Gershwin. “If it wasn’t for George Gershwin I could have been a pretty good mediocre composer,” he said.

With Lord Alfred Douglas and George Gershwin, Wilde and Levant found complex and troubling mirrors in which they both could and couldn’t see their own reflections:

I could have held up a mirror to you, and shown you such an image of yourself that you would not have recognized. (De Profundis, 37)

An evening with George Gershwin is a George Gershwin evening. (Levant, various sources)

The memory of our friendship is the shadow that walks with me here. (De Profundis, 29)

Tell me, George, if you had it to do all over, would you fall in love with yourself again? (Levant)

The shadow of the other, the other’s self-love, the love of the self-love of the other: it’s a melancholy train of association and dissociation. Levant said, “It’s not what you are, it’s what you don’t become that hurts.” Wilde echoes this in De Profundis: “I ruined myself and . . . nobody, great or small, can be ruined, except by his own hand.” But both men veer between a tragic sense of responsibility for having not lived up to potential and a longing, angry gaze at the other who impeded them, who led them down the path to self-disgust, failure.

Oscar Levant was extraordinarily homophobic—he admits as much in Memoirs of an Amnesiac, his second memoir—and Gershwin was . . . a mystery, gay, bisexual, confused? It’s still not clear. In Memoirs of an Amnesiac, Levant writes, “Spender had written a rather shocking, revelatory autobiography dealing in some part with homosexuality, and I said to Isherwood [who was and remained a dear friend], ‘I know that Spender’s half Jewish. Does that account for it?” Does that account for Levant’s half-acknowledged love for Gershwin? He writes: “I was often lightheartedly acrimonious or sarcastic with him, but my real feeling for him was undiluted idolatry.” One wonders if Gershwin was interesting off his pedestal, if he ever was.

Levant’s forbidding and distant father died when he was fourteen. His mother seemed to care most about his success at the piano, and at fifteen dropped him off alone in New York from their home in Pittsburgh so he could take lessons and make his way. Levant relates the story of his father sitting him down on Saturday night, his “night for chastisement,” and telling him the following story:

A son murders his mother and cuts her heart out to present to his sweetheart. With the heart in his hand he rushes off to present it to his fiancée. In his hurry he stumbles, and the disembodied heart that he clutches in his hand cries out, “Did you hurt yourself son?”

Levant says the story made him feel “free and easy.” Which part?

As much as I love Oscar Levant’s melancholic pith, his fuck-it-all daring on the air—“I said outrageous things that not only frightened me, but the whole community,” he writes in Memoirs of an Amnesiac—I think what startled me into caring more about him was that after years of going in and out of Mount Sinai for addiction, clinical depression, shock therapy, he encountered a fellow patient, an old man, who was disconsolate at being prevented from seeing his son and began to cry. Levant put his arm around him and said, “Suddenly I forgot all my troubles. . . . I’d let go of myself” (Amnesiac). He experienced real empathy for the first time, and knew it. He was fifty.

In 1945, six years after Gershwin’s stunning death from a brain tumor, Jesse L. Lasky decided to produce the Gershwin biopic Rhapsody in Blue. It is a really awful film. If you’ve read anything about Gershwin, you know he had a kind of charismatic reserve, watchfulness, and self-involvement. Robert Alda’s lovesick musical enthusiast, now vacuously narcissistic, now vivacious in his ingenuous outpouring of talent, is hard to stomach. The musical numbers aren’t even particularly well staged, for the most part (though it’s always grand to see Jolson—he seems very excited and does a sweet bit of two stepping, and Anne Brown is marvelous singing “Summertime”). Levant was the musical adviser for the film and played the piano parts that Alda mimicked. Most strangely, of all his roles—usually a melancholy version of himself, writing his own lines—here Levant actually plays himself, Oscar Levant, Gershwin friend and hanger-on, re-creating the lines he did say, or might have said, or l’espirit del’escalier, wished he had said. As in most of his films, Levant almost seems like an interloper: he doesn’t really act, he seems to have just wandered on from off set, or as if someone said, let’s get Oscar Levant in this scene to liven it up with a few good lines. But he is more comfortable here, in this biopic rotten egg, than in most of his other films, more relaxed, as though playing Oscar Levant to George Gershwin were the role he had to perform, or perhaps that he was just doing a pantomime of real life. But if you watch it, you can trace the slight amusement in his temper. Is it because Gershwin is alive and dead? (The live Gershwin, for once, doesn’t outshine him?)

Every time a number is performed, the camera cuts to Gershwin’s greenhorn father announcing: five minutes, twelve minutes; his son’s coming up in the theater world measured by how much time he is taking up on stage. One winces. But consider: Rhapsody in Blue was directed by Irving Rapper, who directed Marjorie Morningstar, Now Voyager, and The Christine Jorgensen Story. Levant ends up being the star of Rhapsody in Blue by default, playing the music, speaking the best lines. True, a slightly desultory achievement in a lousy film, but a film, nevertheless, that was given an enormous sendoff by Warner Brothers. Remarkably, in the last scene of the film, after Gershwin’s death, as Levant plays “Rhapsody in Blue” at the Lewisohn Stadium memorial concert, we see the Gershwin faux-love interest (Joan Leslie) watch Levant turn into Gershwin. What a stunning wish fulfillment for Levant!

Freud writes, again in “Mourning and Melancholia,” that “the occasions which give rise to the illness extend for the most part beyond the clear case of a loss by death, and include all those situations of being slighted, neglected or disappointed, which can import opposed feelings of love and hate into the relationship or reinforce an already existing ambivalence.” But what about when there is both, both mourning and melancholia, both death and neglect? I suppose the answer would be, rather obviously, mourning and melancholia.

The irony of this is that Levant had far from an undistinguished career. He was in thirteen films, including An American in Paris, Humoresque, The Band Wagon; he was a radio phenomenon for several years on Information Please in the late ’40s, early ’50s; he was a popular and classical composer, he toured widely for years with a contemporary and classical repertoire, and was for several years the highest paid pianist in the country; he published three memoirs that sold handsomely; he had a reputation as one of the wittiest men in the country.

And he was one of the first people to expose the fragility of their mental health publicly, going on TV repeatedly, both his own television show and Jack Paar’s, to talk about his addictions, his shock therapy, his hypochondria, his general decline in the mid-to-late-’50s. But there had always been a sharp edge to Oscar Levant. It was why people who loved Oscar Levant loved Oscar Levant. He created the persona of the self-aware, self-mocking neurotic, the person in the room who was aware of everything going on in the room but was never the center of attention. He was, in other words, off-center, before off-center became culturally central.

Although he was an extraordinary pianist, accompanying anyone on anything, leading Broadway orchestras, the favorite second piano to Gershwin, later taken on as a student by Schoenberg, it was his wit that got him entry; declared the “wag of Broadway” by Walter Winchell, he hung around with gangsters and the Guggenheims and was one of the best friends of Harpo Marx, the man everybody loved. Women seemed to like him especially, and men with lower levels of testosterone. Hyper-masculine types and the egomaniacal tended to see in his devastating one-liners deflation heading right between their eyes.

He said, “I admire Leonard Bernstein, but not as much as he does,” and, “He uses music as an accompaniment to his conducting.”

He said, famously, “I knew Doris Day before she was a virgin.”

He said of Eisenhower, “Once he makes up his mind, he’s full of indecision.”

The line that got him taken off the air, on live television in 1958: “Now that Marilyn Monroe has converted to Judaism, Arthur Miller can eat her.”

Of Grace Kelly: “She married the first Prince who asked.”

Of himself: “I’m a study of a man in chaos in search of frenzy.”

But there was something wounded, something vulnerable in his mien before he became outright self-destructive. That happened right after he filmed Band Wagon, in 1953, after his heart attack, when fear of death sent him chasing after it, into Demerol addiction.

In the Middle Ages jesters were kept by kings partly for their ability to entertain, but also because they could be expected to tell the truth, wittily, to utter the unpalatable. This license kept their positions secure. Rahere was the jester to Henry I in the twelfth century. (He later became a cleric and founded St. Bartholomew’s Hospital). He was called the “joculator” (which is a wonderful title). But one wonders if the joculators were always so secure. Wit, it seems to me, is always accompanied by the uncertainty of timing, like the goalie’s anxiety before the penalty kick, and the exigency of expectation, and it’s evil twin, deflation. Imagine Dorothy Parker, expected to deliver the epigram, which Oscar Levant called “a wisecrack that’s played Carnegie Hall.” Is that what he considered himself? A wisecrack that played Carnegie Hall? Parker came to loathe the demand that she utter something quotable, some witticism whenever she spoke.

A couple of my favorite lines of Levant’s are actually moments when the anxiety peeks through, when the melancholy nature of wit, the charge of having to deliver the bon mot, is revealed. Friends insisted to Greta Garbo that Levant’s wit was legendary, that she had to meet him. When they were introduced, Levant fumbled, “I’m sorry, I didn’t catch the name,” to Garbo, perhaps the most famous woman in the world at the time. To her witty if not especially sensitive credit, Garbo rejoined, “Perhaps it’s better if some legends remain legends.”

The sobriquet of “the wit” is something of a literary consolation prize, a melancholy distinction for writers and performers whose other work doesn’t overshadow what they managed to say. Even Oscar Wilde, perhaps the wit’s wit, the name that seems a synonym, practically an eponym for wit, who did write, after all, The Importance of Being Earnest, De Profundis, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” lives most vividly where his reputation was first made: in his creation of himself as the outré wit, the decadent, a sower of verbal anarchy in the balanced sentences of epigrams. And perhaps that’s the magic of wit: it’s combustible, anarchic, but perfectly composed and timed, as though it were a form whose internal tensions make it seem almost impossible, which may be why we value it. It’s thought turned into writing in the context of the moment, with supernal cleverness. But ironically, most of our greatest wits haven’t been our greatest writers: Johnson, Wilde, Parker, Sheridan. Of course, the melancholy idea asserts itself that wit is frequently a social form of communication. Clearly, Shakespeare was witty, as was Pope; we know that Lamb was witty, of course, because he occasionally quotes himself, and says in his “autobiography” that he is “more apt to discharge his occasional conversations in a quaint aphorism or a poor quibble, than in set and edifying speeches, and has consequently been libeled as a person always aiming at wit, which as he told a dull fellow that charged him with it, is at least as good as aiming at dullness.” Lamb, of course, was a melancholic of the first order, whose own bout with black bile had to take a back seat to his care for his sister, Mary, who had killed their mother when he was all of twenty-one.

But we need a recording audience, or a recording medium to capture the spirit of wit in its performance. I’m distinguishing the wit of conversation from literary wit. In the case of Wilde or Parker or Levant, the recording has to be a combination of self-preservation in the form of written reportage and self-reportage such as the reprinting in newspapers, in letters, repeated in memoirs. Or in Levant’s recreations of his own witticisms on film. Wit is usually the most transitory of verbal arts. Do you remember the wittiest things you’ve said? And how many of them weren’t spoken to an audience at all but murmured to yourself on the street, or caustically said under your breath at a lecture. The world is full of the ghosts of buried witticisms, the most anonymous of genres. Wit has an audience problem. But if your ego is large, like Wilde’s, you capture your witticisms as epigrams. Parker and Levant were surrounded by writers, newspaper- men and women, columnists. What they said was written down, or passed around as liberally as the Tatler and the Spectator. After awhile they were expected to be witty. They were expected to say something memorable, and it was remembered.

Watching the few Oscar Levant clips that remain from the late ’50s, especially the kinescopes from his appearances on Paar, is fascinating and painful, partially because they seem so anachronistic—we don’t associate painful self-revelation and self-laceration with the late ’50s. With Lenny Bruce, perhaps, but not on national TV. Levant went on Jack Paar, and Paar, to his discredit, seemed to find Levant just clownishly amusing. “For every pearl that comes out of his mouth,” Paar said, “a pill goes in.” Levant said to Paar, “You know, when you’re suffering from deep depression, you cannot make a decision. I first had deep apathy, then relapsed into deep depression. How I long for those deep apathy days.” One thinks of Spalding Gray, years later, crafting monologues out of his life, entertaining, amusing, playing with the line between performance and persona—as Woody Allen had done in the early ’60s—while, as we see Gray in his diaries, wondering whether the creation had gotten the better of him, whether he was locking himself into a performance he’d rather shake, he too, an obsessive hypochondriac. (The joke around Hollywood was that Levant’s epitaph was going to be, “I told you I was sick.”) In his diaries, Gray writes, “It is not enjoyable or easy for me to have a non-narrated private experience and I’ve always known that.”

Levant’s biographers write that “by the mid-thirties, Levant had turned his anxieties into topics of conversation—he had begun to invent the character of Levant the Neurotic, an invention based on his real neuroses. He was, in essence, playing himself, but the line between the real and the acted would always remain blurred.” And he seemed to be able to manage the line to some extent until his heart attack in 1953, picking up an obsession here and a compulsion there: like the number of cigarettes that could be in an ashtray, or what couldn’t be said to him before he performed. (“Good luck” brought him into a fury; in the Barkleys of Broadway [1949], before he performs Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto, if you’re paying close attention, you can hear him saying “goodbye” to two stagehands before he goes on stage.)

Dorothy Kilgallen writes in a column in the late ’30s that “he refers to himself always as a neurotic, but when someone asked him, ‘Are you really neurotic or is it just a pose?’ he looked up blandly and said, ‘I guess it’s just a pose.’” But like Robert Benchley, who became trapped by his role as the confused public speaker in films like Road to Utopia and I Married a Witch, or later Woody Allen’s persona as the neurotic character as leading man (whose character, the film director, is assailed in Stardust Memories by fans of his “earlier, funnier” persona), the indelible character who borrows from his public persona is in danger of not being able to give the character back.

By the time of Jack Paar in the late ’50s, Levant had metamorphosed from the public neurotic to the country’s first public mental patient. He said to Paar, “If I have an argument with my wife, she has me committed. The ambulance is at our house quite frequently. It’s a hell of a way to win an argument.”

Through it all Levant’s ability to produce memorable, even brilliant, lines remained undiminished. He was an extraordinary autodidact. Jean Peters, whom he dated for a while in the ’30s, called him “the only brain in Hollywood.” His talky memoirs are full of casual references to Rimbaud, Dostoevsky, Proust, Oscar Wilde. Levant says (in Amnesiac) of a performance at the Hollywood Bowl that it was “wrought out of my own originality, with the help of extra-sensory perception, somnolence at the moments when I wasn’t playing, and out-and-out passages of Coleridge and De Quincey—when the world adumbrated the last vestige of the peripheral boundary of reality, and unreality.” Not to mention his musical range—he could play anything from Beethoven to Copland, ragtime to Kern, and did play with Ormandy, Toscanini, Beecham. But connecting music and life, he said, “Instant unconsciousness has been my greatest passion. . . . My life is a morbid rondo. . . . Every moment is an earthquake to me.”

I remember the poet Robert Creeley telling me about meeting Beckett in Paris. I’m just a one-eyed American poet who no one’s ever heard of, he said to Beckett, in some grotto of a bar in Paris, but your work is so bleak, what keeps you writing? He said Beckett said he wrote in search of the perfect word, which was “small, and round and speckled.” Perhaps wits are searching for the perfect line, straight and sharp and speckled, since wit is linear, but also frequently defensive—it draws attention and shoots down any response. Wit is usually a closed system, and self-referential. We call wit razor sharp, yes, but we also talk about mordant wit. They aren’t binaries, the deathly and the razor. Think of anything Dorothy Parker said or wrote. “You might as well live,” indeed. “Razors pain you,” but they’re also the sharp edge of aggression. Razor sharp wit frequently cuts both ways. “Anger was my chief raison d’être,” Levant said in Amnesiac. “The first thing I do in the morning is brush my teeth and sharpen my tongue.”

He said, mordantly, sharply, and with melancholy wit: “Judy Garland has become the living F. Scott Fitzgerald of Song” (Amnesiac, 187), and, “My behavior has been impeccable; I’ve been unconscious for six months,” and, “Happiness isn’t something you experience; it’s something you remember.” One wonders if part of the melancholy of wit is saying something admirable, if you’re dubious about being something admirable.

In De Profundis, after his love object, Bosie, has lured him into fatal error and cast him off, Wilde is still crafting epigrams and aphorisms about his genius and the betrayal of his genius, and his incredible stupidity at hooking his bright star to a millstone. He’s pinioned between accusation and self-accusation—I think that’s one of the real fascinations of De Profundis, psychologically. Humility isn’t a philosophy. It’s an act of recognition. And Wilde is still bitterly angry in De Profundis, despite all attempts at achieving a stasis of reconciliation. He writes, “I made up my mind to live, but to wear gloom as a king wears purple: never to smile again: to turn whatever house I entered into a house of mourning: to make my friends walk slowly in sadness with me: to teach them that melancholy is the true secret of life: to maim them with an alien sorry: to mar them with my own pain.” His own recognition is partial, though, as he continues, mournfully, to write, “Nobody is worthy to be loved. . . . Or if that phrase seems to you a bitter one to hear, let us say that everyone is worthy of love, except he who thinks that he is.” Perhaps the supreme vice is making anyone feel that way. Poor Oscar. Oscars. “It is always twilight in one’s cell, as it is always midnight in one’s heart,” Oscar Wilde writes in De Profundis, and that sounds like a kind of epitome of melancholy, a kind of rhapsody in blue.