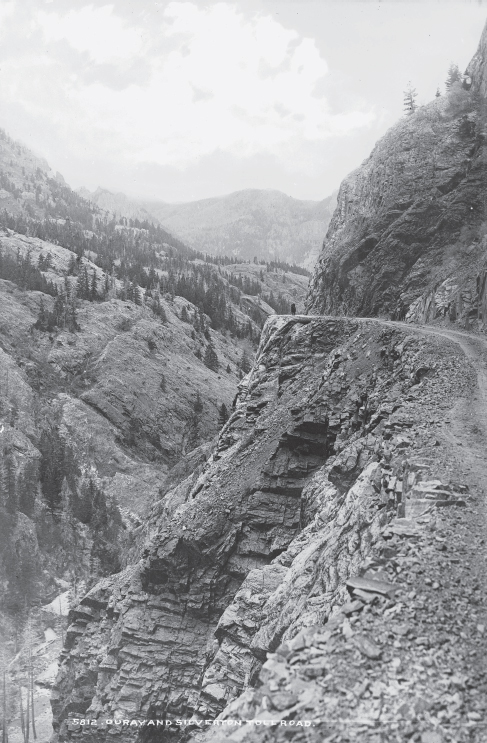

The Ouray to Silverton Toll Road, narrow and treacherous, was blasted through solid rock cliffs. Courtesy of History Colorado–William Henry Jackson Collection.

10

OURAY

On Christmas Day 1875, a little group of prospectors feasted on wild turkey and toasted their good fortune with a big shot of—vinegar. They had no wine or whiskey, so they decided that vinegar was the next best thing. These prospectors really had a lot to be happy about because they’d all found deposits of gold or silver and were busily working their claims. In the summer of 1875, they’d struggled over Engineer Mountain north of Silverton and trudged down the steep slopes into a small valley that was surrounded on three sides by sheer cliffs and towering mountains. Prospectors Gus Begole and John Eckles hadn’t had much luck in Silverton, but it changed in the valley. They were first to discover two small gold deposits, which they named the Cedar and the Clipper. Two other prospectors, who had been fishing, discovered the Trout and Fisherman lodes.

Begole and Eckles continued prospecting in the valley, and in October 1875, they made an extremely rich find they called the Mineral Farm. This claim had parallel veins of gold ore that ran along so close to the surface that they could mine it just like digging potatoes. Several rich silver lodes were found in the high mountains above the camp, including the Virginius, at an altitude of 12,500 feet. This group of silver mines at 11,000 to 12,000 feet became one of the most valuable mining districts in the San Juan Mountains.

A prospector, Andy Richardson, traveled over a high pass, which he named Imogene after his wife, and reached an alpine basin where he made several gold discoveries. Others crossed from the Red Mountain area and tramped further westward to another alpine valley, which they named Yankee Boy Basin. There the Wright brothers discovered a vein of gold that was eighteen to twenty inches wide and even contained a large amount of silver. It became the fabulously rich Wheel of Fortune Mine A townsite was laid out in the valley and named for “Uncompahgre City,” the Ute word for “warm springs.”

The hot springs at the north end of the valley had been used by the Indians for centuries, and they continued their soaks with the prospectors. These Utes and their leader, Ouray, were friendly and often visited the new settlement to trade. They were skilled horsemen and were always ready for a horse race. The Utes bet heavily on their favorites, which usually won.

During the first winter of 1875–76, the few prospectors who remained in the camp ran out of food and supplies, and by spring, everyone was near starvation. Thankfully, spring came early in 1876, and the first men who managed to get through the deep snow were welcomed with joyful shouts. A merchant named Randall brought a stock of dry goods and groceries and started a store in the camp’s first log cabin. Two others began a mercantile business in a tent with a cracker box for a counter and an old sheet-iron stove as their safe. James and Mary Dixon opened the first hotel in their own log cabin. Their guests slept on the floor and provided their own blankets. The first saloon opened, followed by a meat market and a blacksmith shop.

The camp’s name was changed to “Ouray” for the Ute leader, and by the end of 1876, the population was 400. There were 214 cabins and tents, 4 general stores, a sawmill, an ore sampling works, 2 hotels, and a school with 43 students. Soon there were 7 saloons, several gambling dens, and a brothel. When prospectors came into town on weekends, the population swelled to more than 1,000.

On Christmas 1876, everyone was invited to a huge celebration. The ladies cooked a splendid holiday feast, which they served on long tables in the butcher shop. There were plenty of toasts—with traditional spirits—and dancing that lasted into the early hours of the morning. The winter of 1876–77 was severe, and game was scarce. There was no meat for weeks, which made old bacon rinds and dried apples a real treat. Despite rationing, the prospectors ran out of food again and survived on bread and coffee. This second hungry winter taught the town’s merchants to stock up on enormous amounts of food and supplies in the fall so there would be enough to last until the spring snows melted. Food was hauled into the mountains in wagons as far as possible and then loaded on pack trains and taken to remote camps. In the winter, when the snow in the passes reached depths of twenty to thirty feet, all travel stopped, isolating the camps as their meager food supplies dwindled.

In 1876, Colorado became the thirty-eighth state in the Union, and the following January the legislature created Ouray County and named Ouray the county seat. Ouray’s newspaper, the Solid Muldoon, first published in 1879, was an instant success, and readers loved the sharp, sarcastic wit of its editor, Dave Day. He was interested in politics and often ridiculed pompous politicians and devious mine promoters in the paper. The Solid Muldoon was read far and wide, and Day’s humorous, scathing observations were often quoted.

In 1881, Otto Mears began work on a toll road south from Ouray through the rugged mountains to the booming mining camps on Red Mountain. Previous attempts to construct a road had failed. Mears had no special training, and his knowledge was based solely on his experience building toll roads throughout the San Juans. He decided that most of the road would have to be blasted through rock cliffs, creating a shelf road above the Animas River. Men were lowered down the high cliffs on ropes to drill holes, place dynamite, then light the fuses. Their lives depended upon how fast their fellow workers could pull them back up before the dynamite exploded. Five men were killed working on this hazardous section. After months of blasting, Mears succeeded in constructing a narrow, precipitous trail through the gorge more than five hundred feet above the river.

When the road was completed, only the bravest ventured over it to reach the silver-rich Red Mountain camps. Next, Mears and his brave crew set to work gradually widening the trail so a mule-drawn wagon could creep around its sharp curves. He put a toll gate at Bear Creek Falls and built a small cabin for the gate tender, and then he constructed a bridge across a wide chasm and wide waterfall. The road construction cost nearly $100,000 in 1883 money, and in those days, there were no federal funds to help. Otto Mears often said this was the most difficult project he’d ever undertaken. The completion of these few miles of road was considered one of the greatest feats of engineering and road construction in this nation. Mears extended the road from Red Mountain to Silverton in 1884.

In December 1887, everyone in Ouray gathered to cheer the Denver & Rio Grande train when it chugged into the Ouray depot. The completion of an extension line from Montrose meant that passengers who’d been careening and bouncing about on stagecoaches now could ride in comfort in a passenger car pulled by a steam locomotive. The railroad was a cheaper way to ship vegetables, fruit, and ore, and it put the freight wagons and pack trains out of business.

The 1893 repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was devastating to Ouray, causing businesses to fail and banks to collapse. The city turned off the electric street lights and laid off its employees. In 1896, Thomas Walsh, a carpenter who’d been prospecting for years and studying mining technology at night, discovered high-grade gold ore in the discarded rocks from two abandoned silver mines in Imogene Basin. He bought these old silver claims, combined them, and named his new gold mine Camp Bird, after the area’s noisy gray jays. Then he hired five hundred miners for a high wage, began mining gold and built a large stamp mill, which processed two hundred tons of ore a day.

The Ouray to Silverton Toll Road, narrow and treacherous, was blasted through solid rock cliffs. Courtesy of History Colorado–William Henry Jackson Collection.

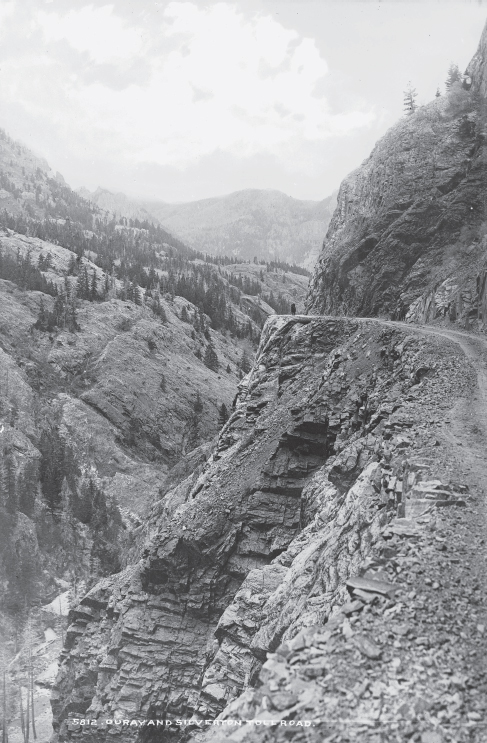

The Wright’s Opera House has an ornate cast-iron front that was believed to make it fireproof. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

The Camp Bird boardinghouse at 11,200 feet altitude accommodated four hundred men and had a game-club room with billiards and poolroom, and a reading room where the miners could spend their off-hours listening to the phonograph or reading newspapers, magazines, and books. The building had electricity, steam heat, hot and cold running water, porcelain bath tubs, and marble-topped vanities with sinks and flush toilets. Good food was served on china dishes by well-dressed waiters as soft music played in the background.

Despite his rapidly accumulating wealth, Tom Walsh remained down-to-earth and was well liked by the people of Ouray. He and his family lived in town, and everyone was always invited to the Walsh parties and dances. He built a public library for Ouray’s citizens, supplied it with over six thousand books, and set up a fund to buy more books annually. The library dedication on July 24, 1901, was a gala affair attended by the governor of Colorado, the former governor, mayors, and dignitaries. Walsh published an apology to Ouray’s citizens in the newspaper, expressing regret that lack of space prevented him from inviting everyone.

From 1896 to 1902, the Camp Bird Mine produced about $4 million in gold per year; that’s about $5,000 per day, making Walsh a multimillionaire. Unfortunately, he developed health problems that were aggravated by Ouray’s high altitude and cold winters and decided to sell the mine. Walsh moved his family to Washington, D.C., and, as a partner with King Leopold of Belgium, opened new gold mines in the Congo. Tom Walsh died suddenly in 1909, but his Camp Bird Mine continued to operate, and by 1916, it had produced over $27 million in gold. His daughter, Evalyn, married Edward McLean, a newspaper heir, and purchased the huge Hope Diamond. Considered the world’s most perfect blue diamond, it’s now in the Smithsonian.

The large warm springs pool opened in the 1920s and draws crowds today. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

Ouray’s good old days ended officially in 1916 when voters approved Prohibition. People in the San Juans voted against the liquor ban but were overruled by the rest of Colorado’s population. Enterprising citizens became bootleggers and hid their stills in old mine tunnels, abandoned buildings, and even in fine Victorian homes.

Ouray’s many hot springs bubbling up along the Uncompahgre River from underground fissures have been a natural draw for weary, aching people for centuries. In 1920, local citizens bought pool memberships, and businesses contributed funds to build a large outdoor pool around the hot springs. The pool opened on July 4, 1927, and a huge crowd came to swim and soak in the water, which was believed to be helpful in curing arthritis and other ailments.

In 1916, federal funds provided by the Good Roads bill, combined with modern road engineering techniques, were used to improve the narrow, rugged wagon road built by Otto Mears into one that could be safely used by automobiles. In 1924, this shelf road became part of the Million Dollar Highway when it opened to cars. The new road brought tourists to Ouray, where they raved about the beauty of its waterfalls and the surrounding mountains. In 1935, Ouray received a WPA grant that put unemployed men to work, making more safety improvements on this highway.

Most of the core of Ouray’s business district and its commercial buildings date from 1876 to 1915. The houses vary from plain log cabins, built around 1875, to many homes in a variety of Victorian and Italianate architectural styles. Much of the town was designated as a National Historic District in 2006.

BEAUMONT HOTEL

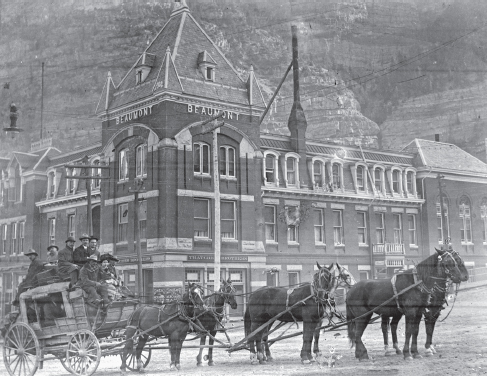

For more than thirty years, the elegant Beaumont Hotel, once the showplace of Ouray, sat neglected, the shabby symbol of an old grudge. Its wealthy owner, Wayland Phillips, furious after a dispute with the city government in 1967, closed the hotel and swore, “It’ll never open in my lifetime!” Then she had the windows boarded up, the doors nailed shut and, as a final insult, she painted the hotel bright pink.

The Beaumont, known as “The Queen of the San Juans,” was a sorry sight, bedraggled and down at the heels. Mice scurried through the grand ballroom where bejeweled ladies and gentlemen had danced the night away. The crystal chandeliers, once festooned with flowers, were draped in spidery cobwebs. Water dripped on the fine furniture through holes in the roof, and the oak floors creaked and groaned as snow piled up in the corners. Expensive hand-painted wallpaper drooped and molded. Cold drafts stirred the gauzy lace curtains, which flapped at the windows like ghosts waving hello. As the years passed, the hotel became more run-down, and there was even talk of blowing it up. Then in 1998, Wayland Phillips died, and the hotel was sold at auction to Dan and Mary King for $850,000.

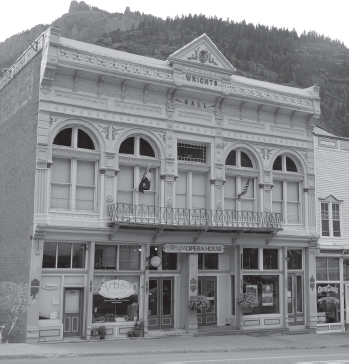

In 1886, the construction of a “really fine hotel” was financed by five businessmen who decided Ouray needed a place where wealthy investors and entrepreneurs could stay while conducting their affairs. The three-story hotel was one of the first buildings in town to have electricity and cold running water. Hot water was piped in from the nearby springs. The hotel was built of brick, and it had a Gothic tower that was two stories higher than the rest of the building. The financiers believed the tower, topped by a golden weather vane, gave the building more class. Like many hotels built during this period, the Beaumont had two front entrances: one on Fifth Avenue for the ladies, while the gentlemen entered from Third Street.

The Beaumont, the “Flagship of the San Juans,” was painted pink and closed for thirty years by its owner. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

The lobby-atrium’s gold velour wallpaper gleamed, and a large skylight bathed the entire area in wonderful light. There were two banks on the first floor, the Western Union Telegraph office, and a gentlemen’s barbershop. An impressive golden oak staircase led to the upper floors, which had forty-three guest rooms with baths. They were furnished with the finest from Marshall Fields of Chicago. There were interior balconies on the second and third floors, circling the central atrium, which opened to the skylight and gave guests a bird’s-eye view of the lobby below.

The grand opening was held July 7, 1887, and the Palmer House in Chicago sent its most experienced employees to help with the gala affair. The distinguished guests included King Leopold of Belgium, Teddy Roosevelt, and Herbert Hoover, then a young mining engineer. Sarah Bernhardt and Lillie Langtry entertained wealthy investors and mining millionaires in the ballroom. Ouray’s newspaper, the Solid Muldoon, raved, “The ballroom was crowded with dancers until daylight.…[T]he hungry did justice to the bounteous spread.”

Both the Beaumont and the Western Hotel sent carriages daily to meet travelers arriving at the train depot. To attract more guests, each driver would loudly shout out his hotel’s wonderful accommodations and special features. As they acquired additional guests, each was seated in the buggy with a flourish, their luggage loaded up, and the driver drove off triumphantly. The elegant Wright Opera House was built across the street from the Beaumont in 1888, and guests could stroll across the street for the evening performance.

By 1896, Thomas Walsh owned many of the old silver mines around Ouray and was mining their waste dumps for gold. The Camp Bird gold mine was flourishing, and on December 10, 1896, Walsh hosted a ball at the Beaumont for over one hundred guests that was described in the Ouray Herald. Bouquets of beautiful cut flowers came from Denver on the train, and the ballroom had “massive banks of pink and white chrysanthemums and carnations. Various colored globes were supplied to the lights, throwing a soft, mellow glow over the many fair dancers who tripped the light fantastic until the early hours.” The journalist continued, “The gentlemen were attired in the faultless conventional evening dress, while the ladies were perfection in attire composed of rich fabrics and adorned in profusion with brilliant diamonds and other precious stones; all presenting a scene of rare beauty.”

In 1911, Chipeta, the popular widow of Ouray, the respected chief of the Utes, and her family visited the town and stayed at the Beaumont. A special committee directed the festivities, and many photographs were taken of her visit. A concert was given in Chipeta’s honor in the evening by the town’s band, and the city fathers took her for a ride in one of the first automobiles in Ouray. This car was also the first to make the journey over Otto Mears’s rugged road from Red Mountain to Ouray. The coughs, belches, and backfires of this mechanical marvel terrified horses, sending them into snorting, bucking fits. Often a horseback rider went ahead of an approaching auto to warn the drivers of wagons and buggies that a horseless machine was coming.

Passengers arrived regularly on the stagecoach to enjoy the luxury of the Beaumont Hotel. Courtesy of History Colorado.

Walsh’s Camp Bird gold mine helped Ouray survive the depression of 1893, but production slowed during World War I. The Great Depression following the 1929 stock market crash brought massive unemployment, business and bank failures. The Beaumont closed many rooms and put furniture in storage, hoping for better days. The hotel was sold in 1941 and fell into Wayland Phillip’s hands in 1967. Then the silly dispute over her parking space caused the closure of the hotel for thirty years.

In 1998, after the death of Mrs. Phillips, the hotel was purchased at auction by Dan and Mary King. The people of Ouray were excited by the prospect of new owners, who were interested in rehabilitating the hotel and eventually reopening it. Older people reminisced about having Sunday dinner in the dining room and recalled special celebrations that had been held at the Beaumont. Families celebrated birthdays, anniversaries, weddings and special occasions here, and the hotel held a special place in the community’s heart. Dan King remarked, “The people are so in love with this building, both the city and its people feel like they own it.”

The Kings began restoration work in the early 2000s, and their first project was the removal of the peeling, pink paint, a laborious process that took five months. The bricks were heated with small propane torches, which caused the paint to bubble. Then it was scraped off, and the bricks were scrubbed vigorously with brushes. The deteriorated bricks and mortar were replaced, and all were restored to their natural color.

Another huge task was restoring the eight different types of handmade windows. They were all removed, repaired, and returned to their original locations. This was a much more expensive project than simply buying new windows. The floors were leveled, repaired or replaced, and the interior walls and roof were stabilized with twelve tons of steel. The plumbing, heating, and electrical wiring were updated, and the building was brought up to code while maintaining its historical appearance.

The wallpaper was especially challenging because there were as many as twelve different layers of paper under the moldy top one. In the lobby, seventeen layers covered the original 1886 wallpaper. Surprisingly, the company that designed this paper a century earlier was still in business and was able to make an exact replica of the original.

The old clock on the staircase landing had been ruined when the hotel was closed, and its repair was questionable. Research showed that this clock was one of only eight that had been made in the 1880s by a clockmaker in New York. The Beaumont’s clock was the original Number Eight, and it needed parts. Experts tracked down enough pieces of the original Clock Number Four on eBay to repair Number Eight. Today, the clock that visitors see quietly ticking away is a combination of the parts of two 130-year-old time pieces.

The Beaumont’s grand opening was October 7, 2002, after a $6 million renovation and restoration. In the lobby, the original registration desk, the tall walk-in safe, and the Chickering grand piano date to 1886. The Tundra Restaurant on the second floor gleams with its original wood paneling and rosewood trim, while upstairs, each guest room has at least one refurbished piece of the hotel’s original furniture. The renovation of the Beaumont earned the Colorado Governor’s Award for Historic Preservation and one of only four Preserve America Presidential Awards. In the National Register of Historic Places, the Beaumont gleams and shines with its old elegance and now boasts a luxurious spa. Once again, this lovely boutique hotel deserves its name, “The Flagship of the San Juans.”

A skylight illuminates the Beaumont’s lobby, the original front desk, and tall antique safe. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

The antique clock displayed on the landing is one of only eight made in the 1880s. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

GHOSTS

The Beaumont is haunted by the spirit of Ellar Day, a nineteen-year-old waitress hired for the 1886 opening. Born in Ouray, she was supporting her young son and was well liked at the hotel. Problems developed when the black pastry chef, Joseph Dixon, became infatuated with Ellar and pursued her relentlessly. When she spurned his advances, the chef became angry and threatening. On September 13, 1887, Dixon, furious and drunk, burst into Ellar’s third-floor room and shot her several times. Ellar’s father, the hotel plumber, trying to protect her, hit Dixon in the head with a heavy pitcher. When his gun was empty, the chef staggered down the back stairs into the arms of the sheriff, who hauled him off to jail. Friends found Mr. Day covered in blood, cradling his dying daughter in his arms.

The Solid Muldoon reported that the chef had been fired by several hotels because of his “wicked temperament,” adding that he’d threatened to kill others. The citizens of Ouray were outraged, and the town’s mood grew ugly. When night fell, an angry mob of masked citizens came to the jail, demanding the keys, but they were turned back by the sheriff. The crowd eventually dispersed, and the town grew quiet. Hours later, an alarm sounded as bright flames sprang up from all corners of the jail. The building burned quickly, and when the flames were finally subdued, the sheriff found Joe Dixon dead in his cell, overcome by the dense smoke. Everyone in town knew the mob had set the jail on fire.

Soon after the tragedy, quiet nights at the Beaumont were shattered by unearthly screams, and blood spatters appeared on the wall in Ellar’s room. Shadowy specters were seen slipping down the back stairs and around corners. In 1896, Alexander Blake, a hotel guest, was awakened by gunshots and threw his door open to see a “blood-drenched girl” running down the hall. Blake followed her and stumbled into the night clerk, who assured him that no one had been shot. Frantically, Blake insisted he’d seen a bleeding girl, despite being told repeatedly, “It’s a ghost—only a ghost!”

Another guest sensed a frightening presence in her room, which was especially strong near the window draperies. When she cautiously peeked behind them, she saw nothing. She said that she was really scared in the bathroom and insisted that something was in there with her.

During the years that the hotel was boarded up with dust, gloom and ghosts, passersby reported hearing faint screams and an occasional pop like a gunshot inside the building. A psychic, who visited Ouray before the renovations, said she heard music and laughter coming from the building, and she noticed the clip-clop of horses’ hooves and the sound of carriage wheels.

When author Anthony Garcez visited the Beaumont, he was drawn to the Buckskin Bookstore on the first floor of the hotel. He interviewed the owner, who said she often heard footsteps in the store when she was alone. There was an occasional banging and knocking in the rear of the building when no one was around. Books flew off the shelves and slammed onto the floor when they hadn’t been touched by human hands. She recalled that three books flew from nearby shelves and landed neatly at the cash register near two customers. She believed the ghosts in the building wanted to make their presence known. She said that she often felt like she was being watched and even whirled around to find she was alone. Other employees reported similar experiences.

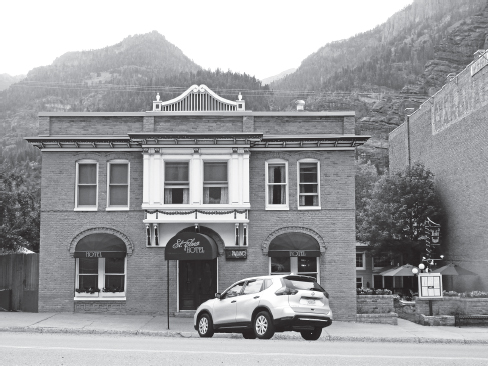

ST. ELMO HOTEL

Young Kitty O’Brien Porter came to Ouray about 1886 with her twelve-year-old son, Freddie. She landed a job managing the Bon Ton Restaurant, worked hard and eventually saved enough money to buy the restaurant. Kitty’s day began about 5:00 a.m. and ran until midnight, seven days a week. She cooked meals, waited on tables, washed stacks of dirty dishes and, at the end of the day, tackled the bills. Kitty’s hard work paid off, and her restaurant was popular in Ouray. The Solid Muldoon expressed the local sentiment: “The Bon Ton combines excellent fare and courteous treatment to a degree that renders living kind of home-like. It is by far the best establishment in Ouray.”

Kitty was quite attractive and had plenty of suitors. She married an electrician, Joseph Heit, on April 30, 1889, and within a few years, the couple adopted a young boy named Francis. When the silver mines closed in 1893, hundreds of miners lost their jobs and were broke, and down on their luck, but they could always get a free meal at the Bon Ton. Kitty never turned anyone away. She survived the economic depression, continued to work hard and saved money.

By 1897, Kitty had enough cash to start construction on a hotel next door to her restaurant. It was completed the following spring, and she named the hotel the St. Elmo. It had arched stained-glass windows with a large second-floor bay window that looked out on Main Street. The rooms had marble-top armoires, brass or mahogany beds, and bright flowery wallpaper. This was an affordable “miners’ hotel,” and the April 21, 1898 Ouray Herald advertised its rates for “regular boarders $1.00 per day: transients $1.50 and new and modern in all its appointments.” Meals were available next door at the Bon Ton Restaurant. Kitty was well liked in Ouray and was everyone’s friend, always ready to extend a helping hand to anyone in need.

Hardworking Kitty Heit’s dream was realized with the opening of the St. Elmo Hotel on Main Street. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

In 1909, fire destroyed many of Ouray’s wooden frame buildings, but the St. Elmo and the Bon Ton escaped the flames. In the fall, a heavy cloudburst sent gallons of water, mud and boulders roaring through town, washing out bridges and roads, and sweeping away buildings. Again, Kitty’s establishments weren’t damaged.

When labor trouble began in the 1900s, Kitty was sympathetic to the union movement. The hotel and restaurant were popular places for Miners’ Union meetings and social events. When striking members of the Western Federation of Labor were deported from Telluride, Kitty took many into her hotel until they could return to their homes. She took care of miners injured during the turmoil and assisted their families. “Aunt Kitty” was beloved and respected by the miners and their families.

The citizens of Ouray were shocked in 1915 when they learned that Kitty Heit had suffered a sudden massive heart attack and died at age sixty-six. She was mourned by many, and the Ouray Herald described her as “the miner’s friend” and paid her tribute:

Her many acts of kindness and charity are legion and she was recognized as the miners’ friend. They were always welcome at her home whether flush with money or down and out. Her hotel came about as near being a real home for the lonesome and homeless as possible and everything was done for the comfort and pleasure of “her boys.” During her residence in Ouray, she had been a regular “mother” to hundreds and no one could possibly be missed more than she.

Kitty’s son, Freddie, took over the hotel, but he lacked his mother’s determination and dedication. Kitty had been discouraged by his laziness and lack of interest in the business, and Freddie did a poor job after her death. Kitty’s second son, Francis, had enlisted in the military and was off to World War I before she died. He immediately headed home upon learning of his mother’s death and was disgusted at the sorry state of her business affairs. Freddie had frittered away everything his mother had worked so hard for. He’d wasted so much money drinking and gambling that her beloved St. Elmo Hotel was on the auction block. When it was sold, the cash went to pay Freddie’s gambling debts.

Broke and depressed, Freddie continued to drink while Ouray’s citizens didn’t hesitate to show their disappointment and scorn. Freddie had few friends left, sank into despair and committed suicide by shooting himself. After Freddie’s death, his wife regained control of the hotel and transferred its ownership to Francis in 1920. He built up the business once again and operated the hotel successfully for three years before selling it.

The bell at the front desk of the St. Elmo often rings mysteriously when no one’s there. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

Through the years, the St. Elmo Hotel changed hands several times and has been restored to its original appearance. Stucco that was slapped over the brick exterior has been removed, a new bay window has been installed above the entrance, and the hotel has been returned to its former Victorian style with antiques and period-style wallpaper.

The parlor’s French doors open onto a patio where the original Bon Ton Restaurant once served Ouray’s citizens. That building was torn down in 1924, and the present Bon Ton Restaurant reopened in 1977 on the hotel’s lower level. The old rock walls, hardwood floors, warm lighting, and beautiful polished mahogany bar enhance its charm. Today’s Bon Ton is regarded as one of the best restaurants on the Western Slope. The St. Elmo Hotel is included in the Ouray National Historic District.

GHOSTS

The St. Elmo has several protective spirits hovering about the premises, paying close attention to its operation. Most paranormal experts believe that Freddie is watching over the hotel that he neglected so badly during his lifetime. Francis was always the responsible son, and some people believe that he, too, is keeping a sharp eye on the hotel—and his brother.

A medium, who was drawn to the St. Elmo on visits to Ouray, said she sensed the spirit of Francis and another man in the hotel. She felt that Francis was very angry because Freddie had lost the hotel and said she believed there had been a fierce argument between the brothers. She even speculated that Francis might have shot Freddie. There is no proof to back up this theory, and most people believe that Freddie took his own life.

Sometimes the St. Elmo’s protective spirits make their presence known by ringing the bell at the front desk. Employees hurry to the lobby, thinking a guest has arrived, but no one is there. They return to their tasks, and then the bell rings again. Sometimes the ringing is ignored, while a live guest waits—and waits.

WESTERN HOTEL

The Western Hotel, built in 1891, has survived the ravages of time, and it is in the National Register of Historic Places and is included in the Ouray National Historic District. Conveniently near the “red-light” district, a tunnel went to one of the popular bordellos and was an ideal place to conceal liquor during Prohibition.

When the Western opened in 1892, it was advertised as “the miners’ hotel with forty-three sleeping rooms, three toilets, and a bath tub.” Some called it a “miners’ palace” with its inviting lobby, richly paneled woodwork, stained-glass windows, electric lights, and fine Victorian furniture. The comfortable sleeping rooms rented for $1.25 a night, and a meal was included for an additional $0.25. The dining room was known for its delicious food, and many townspeople ate there instead of at Ouray’s more expensive restaurants. The saloon was a popular place where hotel guests, miners, and local citizens relaxed with a drink and cigar.

The Western was one of Ouray’s finest hotels and more affordable than the Beaumont, which charged three to four dollars a night. In 1896, the Ouray Plaindealer called it “an authentic hotel of the Old West.” It was sold in 1899, and in 1916, Floro and Maria Flor purchased it. They welcomed travelers, but many of their rooms were rented to miners, who were permanent boarders. Maria took care of the men when they were sick, saw that their laundry was done, helped them write letters and was affectionately called “Mother Flor.” Even though a miner was down on his luck, he was always welcome at the Western.

Built in 1891, the Western Hotel is the largest wood frame building of its era still standing in Colorado. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

The lobby of the Western Hotel looks much as it did a century ago. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

The Flors raised seven children at the hotel and managed to keep it open during the Depression. After Floro died in 1936, Maria carried on the business alone. When the years began to catch up with her, Mother Flor leased the hotel but retained ownership. In 1961, when she was eighty years old, she decided to sell her beloved hotel. Born in 1875, she’d seen many changes: the discovery of silver in Ouray, the growth of the town, the Depression, and two world wars. Mother Flor died in 1963 and was buried in Cedar Hill Cemetery beside her husband.

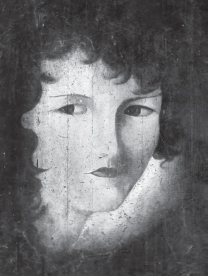

The Western’s lobby, with its high tin ceiling, creaky hardwood floors, and Victorian furnishings, hasn’t changed much since the 1890s. The adjacent saloon, with its original carved wooden bar, potbellied stove, spittoons, and mounted trophies is an echo of the past. Visitors are intrigued by the portrait of a woman painted on the floor, which is similar to The Face on the Barroom Floor in the Teller House in Central City. Both portraits are the work of artist Herndon Davis, and the mysterious face belongs to his wife, Juanita.

The Face on the Bar Room Floor is the work of artist Herndon Davis. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

There are fourteen guest rooms on the second floor, with two that have private baths. Room no. 1 has its original marble sink and hand-painted, blue wallpaper. There have been few changes in these old rooms, and they look like they did one hundred years ago. There are about twenty more rooms on the third floor that are not in use. What the Western lacks in amenities, it makes up in authenticity and character. One visitor summed it up, “Walk into the Western, and you walk into the past.”

GHOSTS

John Hopkins, a young miner, who committed suicide here, did not find peace when he died, and his restless spirit wanders about at night. In 1902, the Silverton mine where he worked shut down, and he was unable to find another job. Hopkins’s loss of income was overshadowed by the recent death of his beloved wife, and grief transformed him from a pleasant fellow into a gaunt, gloomy shadow. He was drowning in sorrow. On December 27, 1902, Hopkins wrote a letter to his former landlady in Silverton. Next, he composed a farewell letter to his mother and asked her forgiveness. Then he undressed, put his folded clothes on a chair, and crawled into bed.

When Hopkins didn’t appear at mealtime for a couple of days, the manager went upstairs to his room and was horrified to find the young man dead. An empty poison bottle lay on the floor, and there was a stack of letters on the desk. The first asked that the letters be mailed and continued, “An inquest will not be necessary. I take my own life—being tired of life and unable to get work, I take this way out of my troubles.” John Hopkins was only twenty-one years old when he was laid to rest in the Hillside Cemetery in Silverton.

Now his spirit, full of remorse and sadness, lingers in the hotel. Sudden cold drafts blow through the narrow hall upstairs, and footsteps are heard when no one’s around. Employees and guests have been frightened by a partial or full apparition of a man that most believe is Hopkins. Some say this entity looks life-like, except for a gray pallor, and a horrible grimace on his face. “He looks like he’s in pain,” shuddered one lady who awoke to see the ghost standing at her bedside.

A guest noticed a stack of clothing on a chair when she first entered her room, but she didn’t think much about it, Later, the clothes were gone. During the night, she was awakened by a cold chill in the room and was terrified to see a filmy figure standing nearby, gazing at her. She said it was “holding out his hands as if he was begging for help.” She said the figure had a “a pleading expression,” and she was so frightened that she just pulled the covers over her head. She lay there, frozen with fear, and when she found the courage to peek out, he was gone.

The misty apparition of a plump woman is occasionally seen on the stairs to the second floor, and a little girl has been glimpsed here, too. Another guest woke up to see a young girl standing near her bed. She was wearing a white, gauzy petticoat and one stocking, and her long, reddish blonde hair was ruffled by a breeze coming through the open window. As the frightened guest watched, the little figure slowly faded away. When she told the owners about her unusual visitor, they shared the story of a previous owner whose young daughter had perished in a snowstorm.

The bar of the Western Hotel has been a popular place for more than one hundred years. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

Two guests in room 18 awoke early one morning to see a woman’s hat floating along the ceiling. When it suddenly fell to the floor, the ceiling light fixture began to gyrate wildly. Then a decanter tumbled off the dresser as if it had been swept aside by an invisible hand. When the activity finally ceased, the frightened couple tried to grab a few winks but were awaked by the bed shaking and bouncing about. The man became very upset and yelled, “For Heaven’s sake, please stop!” The shaking stopped immediately.

Plenty of unusual encounters and scary experiences are recorded by guests in the journals in each room.