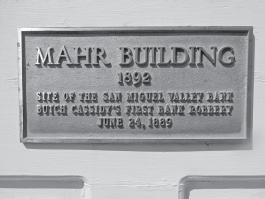

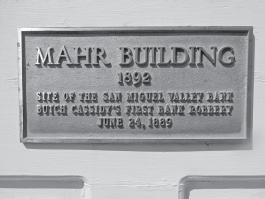

The Mahr Building once housed the bank held up by Butch Cassidy in 1889. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

11

TELLURIDE

On June 24, 1889, Butch Cassidy launched his outlaw career by robbing the San Miguel Valley Bank in Telluride. He and two other cowboys held the tellers at gunpoint, grabbed the cash, about $24,000, and dashed out of town, hooting and hollering. The sheriff quickly formed a posse and followed their trail into the mountains, but they eluded the lawmen and dropped out of sight.

The bank was doing well when it was robbed, and Telluride was flush with the profits of the booming gold and silver mines in the surrounding mountains. The first gold strike had been made in 1875 by John Fallon in a high alpine valley. He named his claim the Sheridan and went on to find three more deep lodes (veins) of gold, which he recorded as the Sheridan group in October 1875.

The Smuggler claim was squeezed in next to the Sheridan on the widest, richest, deepest part of the gold vein, and these claims produced millions of dollars. Prospectors rushed to the high alpine basins surrounded by towering peaks, which rise almost perpendicular above the horseshoe-shaped valley. Here, they found spectacular silver and gold deposits in the alpine basins.

In October 1877, San Miguel was the first settlement in the valley, and two miles east, a second town called Columbia was incorporated by the unanimous decision of its twenty-eight voters. Closer to the mines, Columbia quickly outgrew San Miguel to boast a population of two hundred men and five women. They were becoming frustrated because their mail was going to Columbia, California, in the Gold Country. When they proposed the new name of “Telluride,” for their town, postal officials refused to authorize it. The mail continued to go to California until 1878 when the post office finally accepted the new name and authorized a post office for Telluride, Colorado. This name came from the element tellurium, which forms telluride compounds with gold and silver. Although it was not found in the mountains around Telluride, it is associated with deposits of these rich minerals. Another popular story of how the town got its name is linked to the contraction of “To Hell You Ride,” the phrase often yelled at a hopeful prospector setting out for this remote area.

The Mahr Building once housed the bank held up by Butch Cassidy in 1889. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

The white building (second from the left) once housed the San Miguel Bank, robbed by Butch Cassidy. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

Telluride’s main street, Colorado Avenue, was wide enough for long pack trains to turn around, but despite the wealth of its mines, Telluride’s growth was slow because of its isolation. In 1881, Otto Mears built the Dallas and San Miguel Toll Road, which ran from the town of Dallas, west of the San Juan Range, for twenty-seven miles, skirting the mountains to reach Telluride. Wagons could travel on this road, which helped decrease the cost of transporting ore out of the valley. As more merchants and tradesmen set up new businesses, the population grew. By 1881, corner business lots were selling for twenty-five dollars, and residence lots went for seventy-five cents. Before long, nearly one thousand people were patronizing Telluride’s thirteen saloons and two grocery stores. Water was hauled from the San Miguel River and delivered to homes, saloons, and businesses for ten cents for five gallons.

In 1883, it became the county seat of the new San Miguel County. Many of the richest mines were located in the alpine basins or on steep mountainsides above and could only be reached by narrow, precipitous trails. All supplies, timber, machinery, and equipment were hauled in by pack trains, and the mines could only be worked six months a year because of the deep snows and avalanches. Mine owners built a system of trams to move buckets of ore down cables to the valley below.

Lucien Nunn achieved business success in Telluride through hard work, and he had an interest in the Gold King Mine, south of Telluride. Thinking it would be possible to use power generated by the South Fork of the San Miguel River, Nunn gathered a group of young graduate engineers who were willing to ignore old theories and try new solutions to problems. Learning as they went, the young men who called themselves “Pinheads” taught themselves about wiring, insulating and repairing, took courses in machinery and woodworking, and laid four thousand feet of pipe to conduct water to two Pelton water wheels. They climbed high poles and learned how to string electrical wires.

In 1891, Nunn built a power plant at Ames, a tiny town on the San Miguel River, and equipped it with a high-voltage, alternating current–generating motor. Nicola Tesla, the genius of alternating current, designed and built this first prototype that could generate and transmit electricity over long distances for industrial purposes. The Pinheads strung copper transmission wires over three miles from Ames up a mountain to the Gold King Mine at twelve thousand feet. On June 21, 1891, when Nunn threw the switch, a powerful jet of water hit the large Pelton wheel that was belted to the generator. A brilliant arc shot six feet into the air as everyone gasped, and within the blink of an eye, the Gold King Mine had electrical power to operate its hoists and ore crushers. This was the first long-distance transmission of alternating current power in the world. The cost of operating mining machinery at the Gold King dropped immediately from $2,500 a month to $500. This electric power would be the salvation of the mining industry and transform the use of commercial electrical power forever. This was a huge stimulus to the mining industry as electric power was brought to the Tomboy, the Smuggler and the other high-altitude Telluride mines. Transmission lines were run from the plant at Ames to Telluride, and the Telluride Electric Light and Power Company was organized. Telluride became the first town in the world to become electrified with alternating current generated by falling water. It could even boast of having electric lights before New York or Paris.

Many of Telluride’s original Victorian homes and buildings are included in a National Historic District. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

In the fall of 1891, the Rio Grande Southern Railroad arrived in Telluride, beginning an economic boom. Now ore from the San Miguel Mining District could be transported quickly to Durango’s smelters by rail, greatly improving the mines’ profitability. Droves of immigrants from Scandinavia, France, Germany, Italy, Cornwall, and China came, seeking their fortunes. Telluride soon had over ninety businesses, including blacksmiths, hardware stores, grocery and drugstores, livery stables, barbershops, a furniture store, a brewery, and several laundries, one church, one school, and numerous saloons.

Telluride’s sporting district on Pacific Street, known as “Popcorn Alley,” was lined on both sides with “cribs,” the small one- or two-room houses where prostitutes conducted business. There were about one hundred women here in 1899. The wealthy madams ruled the fancy parlor houses with their orchestras, wine rooms, and plush parlors. Each madam paid $150 a week to operate, and these fees helped keep the town running. The madam, in turn, charged each girl weekly “rent.” The girls who didn’t make the grade in the posh parlor houses worked in the Silver Belle Saloon and Dance Hall or the Senate Saloon, both of which had brothels upstairs. Known as “female boarding houses,” they were still a step above the Popcorn Alley cribs.

The repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1893 dealt a crippling blow to silver mining in Colorado. Men were put out of work as silver mines closed, while those producing lead, copper, and zinc continued to operate. By the beginning of the twentieth century, there were serious labor disputes in the mines. Underground workers labored ten to twelve hours for less than three dollars a shift and had to pay mine owners one dollar a day for their room and board. Due to the mines’ remote locations, most workers had to stay in the boardinghouses while they were working. Conditions were treacherous in the mines, and when the Smuggler-Union introduced a system greatly reducing pay, the men in the Western Federation of Miners went on strike in 1901. The violence escalated, and in 1903, the Colorado National Guard was called out by Governor Peabody, who was strongly anti-union.

Martial law was declared in Telluride, and a military pass was required to be on the street. Union members were beaten, thrown on trains and deported to towns at least fifty miles away. In a futile attempt to keep them from returning, “Fort Peabody” was built on top of thirteen-thousand-foot-high Imogene Pass, blocking a trail into Telluride. The town remained in a state of siege for fifteen months until December 1904 when the $3.00 wage was reinstated. The men went back to work facing the same dangerous conditions in the mines. Despite the labor trouble, Telluride’s mines produced more than $16 million in gold and silver between 1905 and 1911.

Nature created plenty of trouble in the San Juan Mountains, which receive the most snowfall in the Rockies and are one of the earth’s most dangerous avalanche regions. The avalanches were a constant threat to miners and pack trains and created havoc with the railroads, often completely blocking or tearing up the tracks. Early on the morning of February 28, 1902, the night shift of the Liberty Bell Mine had just crawled into their beds in the boardinghouse, while the day shift miners filed into the dining hall for breakfast, when a massive avalanche hit without warning. It started high above on the mountainside, uprooting trees, splintering their massive trunks, tossing huge boulders in the air and creating a seventy-five-foot-wide wall of snow. With a terrible roar, it swept three huge mine buildings into the valley below, tossing debris and bodies about. The alarm was sounded in Telluride, and soon a rescue crew, armed with picks, shovels, and dynamite, was on the way, winding up the trail to the Liberty Bell. A dozen miners had been dug out of the snow when a second avalanche roared down the slopes, burying twenty-four rescuers. The survivors searched frantically, pulling all but two out of the suffocating snow. As the weary men were dragging injured miners and the dead back down the mountain on sleds, a third avalanche swept down, burying several more. Historian David Lavender described one man “saving himself by grabbing a tree as he was being hurled down a hillside; there he clung, deafened and semiconscious, almost suffocated by the snow that had packed like cement into his ears, mouth, and nose.” The deadly Liberty Bell avalanches continued for days, making rescue work impossible, and several bodies weren’t recovered until summer. Twenty-four men were killed, and many more were injured in this avalanche disaster.

Three days after the Liberty Bell tragedy, there were several more avalanches that killed workers at nearby Pandora and swept away buildings at the Smuggler-Union Mine. The storm continued to pound the San Juans as the “White Death” crashed down mountainsides, sweeping away miners, rescue parties and people trying to reach the safety of towns. The railroads ground to a stop, isolating Silverton and Telluride.

The first decade of the twentieth century ended disastrously when the dam on a nearby lake burst, sending torrents of water crashing down the San Miguel River. It damaged the Ames power plant and tore up miles of railroad track, isolating Telluride. Then in July 1914, there were tremendous cloudbursts with torrential rain that overflowed creeks and rivers, sending water sweeping down Cornet Creek, smashing through a dam. A rushing wall of water, filled with tumbling boulders and ripped-up trees roared down Colorado Avenue, sweeping homes and businesses away. The lower floors of the Miners’ Union Hospital and the New Sheridan Hotel were filled with twelve feet of thick mud, and Colorado Avenue was blocked by a five-foot-high wall of tangled debris. Luckily, only one person was killed in the disaster.

Many homes were swept away in the devastating Cornet Creek Flood of July 27, 1914. Courtesy of Denver Public Library–Western History Collection.

When Colorado enacted Prohibition in 1916, many saloons closed, while others operated as soda parlors. Telluride’s city treasury quickly levied special license fees on soda parlors to replace the lost liquor establishment fees. Since law enforcement was very lax, the town’s stone brewery continued churning out suds, and stills popped up in the hidden gulches. Moonshiners produced so much hooch that they were able to ship their choice batches to New York City. Al Capone bought large quantities of booze, and private clubs in Denver proudly served “Telluride Shine.”

Bootlegging helped the town survive during the late 1920s when the mines started shutting down because of the low prices of gold and silver. It was a dark day in the struggling town when the stock market collapsed in 1929, and as businesses failed, the population plummeted to six hundred. As banks closed their doors, depositors lost all their money. The president of the Bank of Telluride, Charles “Buck” Waggoner, concocted an elaborate scheme using secret bank codes to swindle six of the largest financial institutions in New York City of $500,000. He used the money to cover losses in the Bank of Telluride and to repay his depositors, saving the hard-earned wages of the miners and the town’s citizens. When the scheme was finally discovered, the press gleefully reported the story about a little country banker who’d fooled the wealthy New York bankers. He was compared to Robin Hood, who stole from the rich and gave money to the poor. Everyone in Telluride was very grateful to Waggoner for salvaging their funds, but the big banks were furious, and he spent several years in prison.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the old mine and mill tailings were reworked, yielding valuable base metals and gold, but this wasn’t enough to keep the town going. The Idarado Mining Company purchased the Telluride mines and connected them to large mines at Red Mountain with a five-mile-long tunnel through the mountain. The Idarado mines and mill operated until 1978 but then shut down operations, and the population fell to around four hundred. Many feared it was only a matter of time before Telluride became a ghost town.

Telluride was resurrected in the 1970s by another kind of gold: “white gold,” better known as snow. The new ski resort reshaped the economy, revived the Telluride community, and put the town back on the map. In 1978, two Colorado natives, Ron Allred and Jim Wells, with the backing of their Benchmark Corporation, assumed control of the ski area. They built Mountain Village, a resort with a first-class ski area, installed snowmaking equipment and lifts, and carved out new beginner terrain. In 1996, a gondola was installed to connect this luxury community with the town of Telluride, now a National Historic District.

NEW SHERIDAN HOTEL

The two-story wood frame Sheridan Hotel was built in 1891, but it was destroyed by fire in 1894. It was rebuilt with bricks in 1895 and became the “New Sheridan.” The front entrance opened into the elegant saloon with its calfskin wall coverings and mahogany and cherrywood bar imported from Austria. The matching back bar had large Corinthian columns framing the thirty-foot-long diamond dust mirror from France. Brass chandeliers cast a warm light on the pressed-metal ceiling, and the popular bar was separated from the lobby by leaded glass room dividers. Sparkling ore specimens from local mines were displayed in glass cases in the impressively furnished lobby. A third floor was added in 1899, and the hotel had electricity and modern plumbing with steam heat.

The New Sheridan was known all over Colorado for its delicious cuisine—said to surpass Denver’s Brown Palace. Oysters, fancy ices, caviar, and lobster were packed in ice and shipped by rail to Telluride for lavish banquets and grand balls. Waiters in tuxedos served guests truffles and quail on fine china, while the snooty sommelier extoled the virtues of selections from one of the West’s finest wine cellars. The Japanese pastry chef whipped up extravagant desserts for diners, some of whom had been grateful for biscuits and beans before a lucky strike made them millionaires.

Wealthy business men took their wives to dinner in the mirror-lined American Room and then danced the night away to tunes played by musicians seated in the balcony. They met their mistresses in the more intimate Continental Room, which had a discrete rear entrance. There were sixteen private dining booths, draped in heavy, plush velvet, ideal for cozy tête-à-têtes. Every booth had its own telephone that could be used to summon a waiter when he was needed—and to avoid any embarrassing interruptions.

In 1903, William Jennings Bryan addressed a crowd in front of the New Sheridan Hotel. Courtesy of History Colorado.

In October 1903, three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan spoke to a huge crowd of supporters from a grandstand in front of the New Sheridan. He delivered a reprise of his stirring “Cross of Gold Speech” supporting free silver, which he’d originally given at the 1896 Democratic convention in Chicago.

The New Sheridan Hotel on Colorado Avenue is popular with locals and tourists. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

The hotel hosted Lillian Russell, Sarah Bernhardt, Lillian Gish, newspaperman Damon Runyon, and Eugene Debbs, the union leader. During the Telluride labor struggles in 1903–4, when the town was under martial law, federal troops took over the hotel for their headquarters. They even imprisoned a union leader, Charles Moyer, for six months in an upstairs hotel room.

The New Sheridan fell on hard times in the 1940s when many large mines stopped producing lead and other metals, sending Telluride into a decline. The hotel changed hands several times, but it was neglected and most of its fine furniture was sold to Knott’s Berry Farm in California. In 1977, a new owner completely renovated the hotel and furnished it with fine antiques. The elaborate Victorian wallpaper was replaced with an elegant replica, and today the historic saloon looks just as it did in 1895. There’s fine dining in the Chop House and the Parlor, or guests can eat while they soak up the sunshine and mountain views on The Roof. The hotel is part of the National Historic District and is listed on the National Trust for Historic Hotels of America

GHOSTS

The New Sheridan, like many hotels that date back a century or more, has a few guests who’ve remained through the years. There are unexplained creaks and groans, quiet footsteps in the night, cold drafts, and mysterious shadows. The hotel was investigated in 2011 by StanJan Paranormal, who posted their findings on YouTube. Antonio Garcez, author of Colorado Ghost Stories, interviewed a maid at the hotel who told him about her strange experience. She had closed and locked the door of a vacant room when she suddenly saw a man walk right through the door. He didn’t speak, walked by, and went to the end of the hall where he passed right through the exterior wall. Frightened, she screamed for her co-worker, who told her about some of her own strange experiences. This other housekeeper had been cleaning a room when she heard a man speaking to her. No one was around, and the room was empty. Frightened, she hurried to finish when a man started singing an old song, “Rosemarie, why don’t you dance with me?” She stopped her work again to make sure the hall and the nearby rooms were empty. She found no one. She was serenaded several different mornings, and there was never anyone around. Sometimes she heard a light cough and sounds like someone was clearing his throat repeatedly.