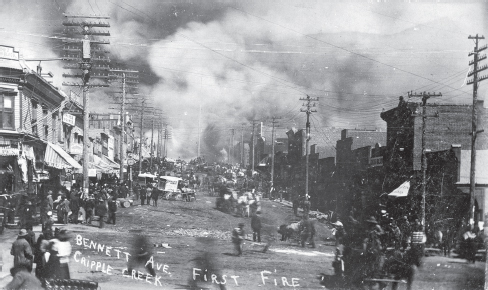

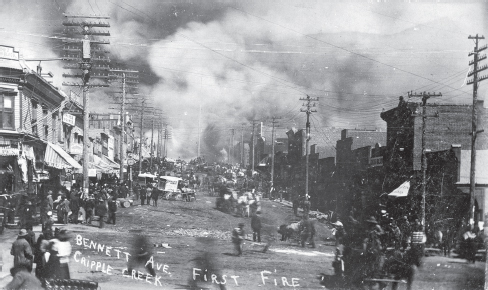

In April 1896, Cripple Creek endured two disastrous fires within a period of ninety-six hours. Courtesy of History Colorado.

17

CRIPPLE CREEK

Cripple Creek was the scene of Colorado’s last gold rush, and it ended the economic depression of 1893 when 50 percent of the men were unemployed. Cowboy Bob Womack’s discovery of unlikely looking gray rocks near a creek where a cow broke her leg started a boom that produced millions of dollars’ worth of gold.

Womack drank too much, and nobody would loan him money to develop his new claim. He put a few samples of this gray rock in a window of a Colorado Springs furniture store, hoping to attract an investor. A sharp-eyed, self-taught geologist recognized these samples as a complex mineral that combines with gold or silver. He learned the location of Womack’s claim and hurried to stake his own claim nearby. Next, he marked off a six-square-mile area around Womack’s discovery, named it the Cripple Creek Mining District, and set to work.

Womack woke up one morning to realize that in a drunken stupor he’d sold his claim for a paltry $500. When developed, it became the Gold King Mine, which produced $5 million in gold. Womack made more potentially rich claims, but he always sold them before trying to mine any. He celebrated the sale of one claim on Christmas Day 1893 by passing out $1 bills to children in front of his favorite saloon. In 1909, Bob Womack died in Colorado Springs without a penny.

It’s ironic that much of Cripple Creek’s gold was found in a ten-square-mile area where many rich discoveries were made by dentists, firemen, teachers, and clerks who knew nothing about prospecting. A pharmacist, who had no idea where to look for gold, tossed his hat into the air and started digging where it landed. He hit a rich vein, which became the Pharmacist Mine, making him one of the district’s first millionaires.

Prospectors Pat and Mike were down to their last dollar and decided they’d dig at the next spot their dog lifted his leg. The pup stopped, and they dug and struck a wide band of gold, which became the wealthy Last Dollar Mine.

Realtors Horace Bennett and Julius Myers bought 640 acres, platted a town site, named the principal streets after themselves, sold lots, and made a quick million dollars. They called the new town “Fremont.” After just two months, there were eight hundred people living in tents, cabins, and shacks scattered around Fremont. When the town was awarded a post office, the government changed the name Fremont to “Cripple Creek.”

In addition to hopeful prospectors, hordes of hustlers, gamblers, and con men—scheming to grab a share of the golden fortune—headed for Cripple Creek. Soon there was an abundance of saloons, brothels, and dance halls lining Myers Avenue, the red-light district. Prostitutes were banned from plying their trade on Bennett Avenue, the business boulevard of banks, brokerage houses, and hotels. By 1894, there were ten thousand people in Cripple Creek, with five hundred more arriving every month.

The year 1894 brought the first labor strike. Miners worked ten hours for less than three dollars a day, and their working conditions were deplorable. Injuries and deaths from explosions, falls, cave-ins, poisonous fumes, and falling rocks were common. The loss of an arm or leg or having one’s head blown off was a daily risk for them, and there was no compensation for families when an accident happened. Miners joined the union of the Western Federation of Mine Workers (WFM) for support. When their demands for an eight-hour day for three-dollar wages were denied by mine owners, they went on strike.

Winfield Stratton, who’d become Cripple Creek’s first millionaire, remembered his hungry times as a prospector and met the union’s demands at his Independence Mine. His hopes that other mine owners would follow his example were dashed, and tensions between labor and management escalated into violence and mayhem. There were gunfights, buildings were dynamited, two men were killed, and the state militia came twice to establish order in Cripple Creek. The miners’ strike lasted five months, and the union finally won an eight-hour workday for a wage of three dollars.

Railroad tracks were gradually replacing the rough stage roads to Cripple Creek, and the Florence & Cripple Creek Railroad (F&CC), financed by the Denver & Rio Grande, was the first to steam into town on July 1, 1894. The entire population turned out to cheer and celebrate, and in December 1894, the Colorado Midland Railroad arrived. Now two railroads were busily hauling gold ore to the smelters from mines in this area. Spur lines were built to the two dozen satellite towns and their mines scattered through the surrounding hills. The Cripple Creek Mining District eventually produced more millions of dollars in gold than California did in the 1849 gold rush.

Disaster struck on the morning of April 25, 1896, when a scuffle between a bartender and his girlfriend tipped over a stove, starting a fire. Fanned by strong winds, the flames took off, destroying most of the Myers Avenue red-light district. Then it blew toward the business district, consuming banks, shops, and the post office with its twenty-five thousand pieces of mail. Within three hours, Cripple Creek suffered over $1 million in damages, two lives were lost, and 3,600 people were homeless.

In April 1896, Cripple Creek endured two disastrous fires within a period of ninety-six hours. Courtesy of History Colorado.

Just three days later on April 29, a pot of grease caught fire in a hotel kitchen, and the flames exploded into a raging inferno. The April 30, 1896 Rocky Mountain News reported that “the whole city rushed to the scene, dropping tools from their hands. The fire jumped with a roar like a hungry giant at his prey. Floods of water and the demolition of buildings with deafening explosions of dynamite didn’t stop the fire, and men stood with tears running down their cheeks, helpless.” Terrified people piled their children, pets, and possessions into wagons and rushed to leave the burning town. The fire roared through fifteen blocks of businesses, destroying four hundred buildings, and leaving six thousand people homeless.

When word of this disaster reached millionaire Winfield Stratton, he quickly formed a relief committee; volunteers collected tents, thousands of blankets, and diapers. Stratton loaded the supplies on a two-car train in Colorado Springs, and it headed for Cripple Creek, stopping at towns along the route to pick up more donations. When the supply train whistled into Cripple Creek late on April 29, it was greeted with thankful cheers and plenty of grateful tears. The supplies were distributed among the bedraggled, sooty citizens, many of whom had lost everything. Stratton organized a second relief train carrying food, which volunteers rushed to gather, taking everything from canned vegetables, cases of canned beef, beans, condensed milk, and crackers, to every loaf of bread in town. They tucked in jelly and preserves, liquor, and piles of cooking pots. When the food train arrived at dawn in Cripple Creek, it was met by grateful, hungry people who cheered and cried as the food was distributed.

Cripple Creek was soon clearing the disaster debris, and the city council passed an ordinance requiring all new commercial buildings to be built of brick. Most of the handsome new brick and stone buildings were decorated with rosettes, stained-glass windows, cast-iron pillars, and dated 1896. Six months after the fires, the population had increased by ten thousand. By 1900, Cripple Creek was Colorado’s fourth-largest city, with a population of twenty-five thousand. At its height, the mining district’s population peaked at fifty thousand. Over five hundred mines had produced more than $18 million in gold by 1900, and the mining district’s total production was well over $77 million. Cripple Creek and Victor boasted twenty-eight millionaires and countless others who’d become incredibly wealthy.

Another labor strike in 1903–4 lasted fifteen months, and it was one of the bloodiest and most violent in Colorado’s history. Governor Peabody called out the National Guard and declared martial law in Cripple Creek. Over two hundred union members were rounded up, loaded on trains, dumped across the state line, and forbidden to return. Mine owners banned organized labor in the Cripple Creek Mining District, and gold production was cut in half, scaring off investors and damaging the mine owners financially.

In 1906, Carrie Nation, called the “hatchet-face mascot of the WCTU” (Woman’s Christian Temperance Union), who specialized in invading saloons and chopping bars into pieces with her hatchet, came to Cripple Creek. As she marched up Bennett Avenue, leading a parade of temperance sympathizers, doors of liquor emporiums were slammed in her face. When she discovered Johnny Nolan’s Saloon was open, she stomped in, axe raised. When she saw Nolan’s prize, the Botticelli painting of a nude, Birth of Venus, she screamed, “Hang a blanket over that trollop! If that naked witch isn’t covered up, I’ll chop her to shreds!” She charged at the painting, hatchet raised, and began slashing at it. Nolan grabbed her, spun her around, and knocked the axe from her hands. The sheriff speedily hauled Carrie off to jail, where she spent the night cooling off. In the morning, Nolan himself bailed her out and loaded her on the train for Colorado Springs. Always a gentleman, Johnny Nolan politely advised Carrie not to return to Cripple Creek.

By 1910, the price of gold was falling, and water was seeping into the deep mine tunnels from underground streams. Pumps could not clear the tunnels, and as workers drilled deeper than eight hundred feet, the water flow increased. Large tunnels were built at great expense to drain off the water, but the flooding continued. During World War II, the government ordered all mines that weren’t producing copper, lead, or zinc for the war effort to close. Only a few gold mines were able to resume operations after the war ended, and most shut down permanently in the 1950s.

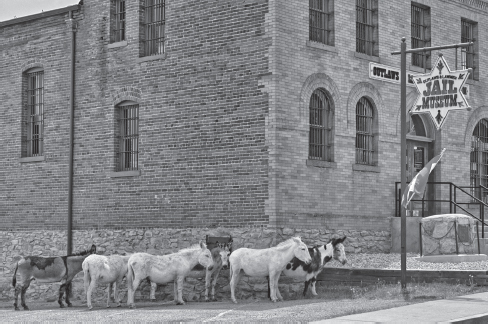

Descendants of burros that worked in the mines roam Cripple Creek’s streets. Courtesy of Tom Williams.

Cripple Creek’s population dropped to a few hundred people, who began joking that their four-legged population was larger than the two-legged one. When the mines closed, the little burros that had pulled ore carts and wagons and carried supplies and equipment were out of work, just like the miners. Turned loose to roam the streets, they demolished gardens, tipped over garbage cans, and begged for handouts. They became children’s pets and hung around posing for pictures with tourists. They still wander around town. In 1931, crowds poured into Cripple Creek for the first Donkey Derby Days, and this popular event has taken place every summer since. All proceeds go to the Two Mile High Club for the care and feeding of Cripple Creek’s burros.

In 1990, Colorado voters approved limited-stakes gambling in Cripple Creek, Black Hawk, and Central City, and their old buildings had facelifts before becoming casinos. Gold mining resumed at the Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mine, an open pit mine where gold is recovered by heap leaching. This mine is now the largest gold producer in Colorado.

IMPERIAL HOTEL

After the ashes of the devastating 1896 fires cooled, construction of the three-story brick Imperial Hotel was started, and it was completed before the end of the year. The hotel was leased by a widow, Mrs. E.F. Collins, who called it the Collins Hotel. She rented rooms to mining engineers, stockbrokers, assayers, and professional men for three dollars per day, with meals included.

In 1906, a Mrs. Shoot took over the business, renaming it the New Collins Hotel. She annexed the three-story building next door and connected the two structures with an elevated passageway. This hotel had seventy rooms with steam heat, electric lights, private bathrooms, and a large dining room, which could seat three hundred. Many elegant dinners and soirees attended by gilt-edged guests from England, Wales, and France were held at the hotel, and the society columns were filled with news of club socials, ladies’ luncheons, and elaborate teas hosted at the New Collins. Despite the hotel’s popularity, Mrs. Shoot fell behind on her mortgage payments, and George Long, who held her note, foreclosed in 1910.

Long was a wealthy English aristocrat who’d come to America to escape the gossip after he married his first cousin Ursula. A descendant of royalty, George received a monthly stipend from the British Crown, which enabled his family to live very comfortably. George and Ursula renovated the hotel and converted it into a stylish Victorian establishment, changed the name to the Imperial Hotel, and ordered expensive new furniture.

The Imperial Hotel was built in 1896 after two disastrous fires destroyed much of Cripple Creek. Courtesy of History Colorado.

The Longs lived in an apartment in the hotel with their young son, Stephen, and daughter, Alice, who was mentally ill. She had tantrums and flew into rages so violent that the Longs were forced to lock her in the apartment alone when they had hotel responsibilities. George Long was described as a shy, “gentle wispy man,” whose hearing was impaired, and he preferred to putter around in his basement shop while his wife entertained their guests.

The Longs’ fleet of seven shiny Pierce Arrow limousines, driven by smartly liveried drivers, met the train from Colorado Springs every day. They welcomed travelers and drove them to the Imperial, where as many as three hundred were served a fine luncheon with plenty of wine in the spacious dining room. Then everyone clambered aboard the train for the trip back down the mountain to Colorado Springs.

In 1940, George died from a fall down the basement stairs, and when the accident was investigated, it turned out to be murder. An angry Alice had walloped George in the head with an iron skillet when he was coming up the stairs. Then she pushed him, causing his fatal fall backward down the steps. Alice spent the rest of her life in a mental institution for the crime.

Ursula Long was heartbroken by her husband’s death, but she managed to keep the hotel open for four more years and then gave up. The Imperial sat vacant and neglected for decades until Wayne and Dorothy Mackin purchased it in 1946. This optimistic young couple saw potential in the dismal, down-at-the-heels building, sitting crookedly on its steep hillside lot. The fine furnishings were gone, and the only things left in the faded lobby were an old potbellied stove and a scuffed roll-top desk.

The Mackins began a room-by-room renovation: scrubbing away accumulated grime, scraping off old paint, removing stained, peeling wallpaper, refinishing and polishing the hardwood floors, and renovating the kitchen. They remodeled the owners’ apartment, bought cheap furniture at auctions, and moved in. By the summer of 1947, the kitchen was functional, and the dining room was ready for customers. Their hard work paid off, and the Imperial soon gained a reputation for serving good food

Imperial Hotel hosted the longest-running melodrama theater in the nation. Courtesy of Tom Williams.

In 1947, the Mackins presented the first performances of an old-fashioned melodrama, which received rave reviews. They hired a troupe of traveling performers and converted the basement into a cabaret-style theater, called the Gold Bar Room Theater. In 1953, they opened ta luxurious lounge in the Red Rooster Room and introduced the new Imperial Players as permanent performers. By 1996, their renowned productions had become the nation’s longest-running melodrama theater. The Mackins’ son, Stephen, took over management of the hotel in the 1980s and continued its operation until the Imperial was sold in 1991. After Colorado voters approved legalized gambling, the hotel underwent several ownership changes and subsequent renovations.

GHOSTS

The ghost of George Long, who loved the Imperial, might be responsible for the mysterious activity in the hotel’s casino. A night-shift casino employee named Richard Duwe was startled when a slot machine suddenly began dumping out coins. The casino was closed, and no one was around. Security cameras showed that one slot machine spitting out hundreds of dollars in coins—although all the slots have a variety of mechanisms to prevent this. The Colorado Gaming Commission examined the machine and found no evidence of tampering or malfunctioning, leaving many to wonder if George had been tinkering around.

On another night, after the casino closed, quiet and empty, Duwe heard the familiar “ding” of a coin dropping into a slot machine. He radioed security, thinking that a customer had managed to stay after closing, hidden, and now was trying his luck. Duwe and the security officer searched the entire casino and found no one. None of the slots had its “Coin Accepted” light on. The security officer settled the question, saying, “It was probably just George!” Duwe became convinced that there was a ghost sharing his night shift at the Imperial,

Several people who have abilities as a medium have picked up the presence of various spirits in the hotel, and these “sensitives” have noticed there are different levels of both negative and positive energy present in different areas. The old lobby has been restored and looks just like it did over one hundred years ago, but most guests don’t linger here, saying they feel like they’re being watched. Others may get a “creepy” feeling on the stairs where George Long fell to his death, and still more say they sense a presence downstairs. Employees have seen shadowy figures and felt mysterious touches. Remodeling often stirs up resident spirits, and several paranormal investigators commented that one entity was very angry about the presence of so many people in the hotel casino.

There are unexplained loud banging sounds, and employees have heard scratching sounds at the door to the Red Rooster Bar—as if someone was trying to get it open. This was once the apartment where the Longs locked Alice when she became violent. Rick Wood, who formerly led the Cripple Creek Ghost Walk Tours, said that George often wandered about the halls of the Imperial and that he was especially active in rooms 39 and 42. The water faucets was often turned on and left running in these bathroom sinks, and the doors opened and closed by themselves. Through the years, George has been blamed for jammed dresser drawers, stereos that don’t work, and doors slamming unexpectedly. Wood said that George was always blamed if a woman’s behind was discreetly patted. One man who stayed at the hotel said he spent a restless night and kept waking up. In the early morning hours, he said, “I woke up and thought I saw a man in a straw hat and white shirt standing by my bed. I guess I was dreaming, but it sure seemed real.”

Jeff Belanger, author of the book The World’s Most Haunted Places, interviewed Stephen Mackin, who spent the first seven years of his life in the apartment—now the Red Rooster. Stephen said his family never publicized the hotel’s ghost, although they were aware of its presence and referred to it as “the silent owner’” Mackin said, “I’m sure that George is still there somehow. Nobody in my immediate family ever saw him, but I had a director for my theater who saw him. I also had a couple of actors who saw him.” He continued, “A couple of people who worked in the kitchen also saw him.” He explained, “The things that we did see from George were all friendly things. There was nothing spooky or evil or anything like that.” One actor who saw George standing behind the bar downstairs recalled “a well-dressed man with a balding head with a thin ring of ‘monk-like hair.’” That fits George’s description perfectly.

ST. NICHOLAS HOTEL

By 1893, Cripple Creek had eighty practicing physicians but no hospital. The town’s citizens appealed to the Sisters of Mercy to open a facility to care for the sick and injured. They even offered to donate wooden frame house that could serve as a small hospital. On January 4, 1894, the Sisters of Mercy opened St. Nicholas Hospital in the donated house, and they treated three hundred patients the first year.

In April 1896, when flames from two disastrous fires almost destroyed Cripple Creek, the nuns hurried to evacuate the hospital and move their patients to safety. While the nuns were working frantically, a member of an anti-Catholic group sneaked into the hospital’s kitchen and planted dynamite in the stove’s chimney. He wanted to totally destroy the nuns’ hospital, but his evil plan backfired when the dynamite suddenly exploded and blew off his leg. The merciful sisters treated his injury and calmly evacuated him with the rest of their patients. Cripple Creek’s disastrous fires left thousands homeless in cold weather, but luckily, the hospital was spared. After the flames were subdued, the nuns brought their patients back to their little house. They were surprised to find the dynamiter’s leg, minus his shoe, which had been blown off and landed in their tea kettle.

The St. Nicholas Hotel was once a hospital, opened in 1898 by the Sisters of Mercy. Courtesy of Tom Williams.

As Victor, Cripple Creek, and their satellite mining communities grew, the nuns bought land on a hill overlooking Cripple Creek and hired a Denver architect to design a state-of-the-art hospital. When it was completed, the three-story brick building had steam heat with hot and cold running water, electricity, and a modern surgery department with an operating room. St. Nicholas Hospital had twenty-six patient rooms, one of which was elegantly furnished by mine owner Bert Carlton to be used by his ill or injured employees. Eventually, a small ward was added for the mentally ill. The nuns lived on the third floor, while the orderlies’ quarters were in the attic above. The huge boiler in the basement kept the place toasty in the winter, although it used over one hundred pounds of coal a day.

The hospital opened in March 1898, and the first patient was a miner who’d had an unfortunate fall down a mine shaft. During a smallpox epidemic in 1901, the nuns vaccinated as many as possible and cared for all of the sick. During the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic, the hospital was inundated with deathly ill patients, and so many people died that bodies were piled outside the funeral home. In 1925, the nuns sold St. Nicholas to a group of physicians, who operated it as a private hospital. It remained open until 1960, when the county bought it for one dollar.

In 1972, the hospital closed and sat vacant for years until it was purchased in 1995. It was remodeled into a hotel with fifteen Victorian-style rooms, all with private baths. The massive safe in the office that was manufactured around 1900 has been in use for over one hundred years. Numerous photos of the hospital’s early days are displayed throughout the hotel, and there are sweeping views of Cripple Creek, its mines, and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

GHOSTS

Spirits of some long-departed patients and a few dedicated nuns drift around the St. Nicholas, but Stinky can’t be missed. A foul odor around the hospital’s back stairs is a tip-off, and occasionally, someone catches a glimpse of a worn-looking miner. Sometimes only half of the miner’s body is seen floating down these back stairs. There are many stories about Petey, an orphan, who lived at the hospital and was taken care of by the nuns. He’s a mischievous spirit and is often seen darting around the hotel. His favorite spot is the tiny Boiler Room Tavern, where he moves bottles around, hides keys, and creates small disturbances.

When the hotel owner was working in the small office behind the old cashier’s booth in the lobby, she was startled by a strange sound. Looking around, she saw a tall, thin man in a long coat and wearing a derby. He just looked at her and then vanished. Another employee was frightened when she saw this thin man, similarly dressed, pass by her and slowly disappear while she watched. A group of six men were standing at the small tavern bar talking when the doorbell rang. When one of the men answered the door, no one was there. He said he felt something touch his shoulder, and he turned to see a tall, shadowy figure walk past him and right through the back wall.

Patient rooms have been renovated into comfortable guest rooms. Courtesy of Tom Williams.

Guests in room 11, which was once the hospital’s operating room, have been awakened by the sound of crying. They’ve seen a little girl standing at the foot of their bed, and then she vanishes. Guests have been awakened by children laughing and the sounds of a ball bouncing about on the third floor. This paranormal activity has occurred when there are no young children staying at the hotel.

The St. Nicholas Hotel has been investigated by several paranormal groups, including Southwest Paranormal and Spirit Chasers. Their observations and video recordings can be seen on the internet. Another group of investigators from Digital Dowsing and Darkness Radio spent three days tracking the spirits at this old hospital. They obtained some interesting EVPs and a video that can be seen on the internet.