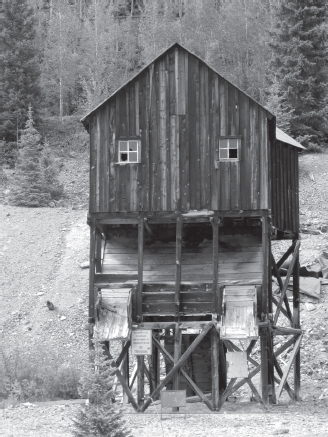

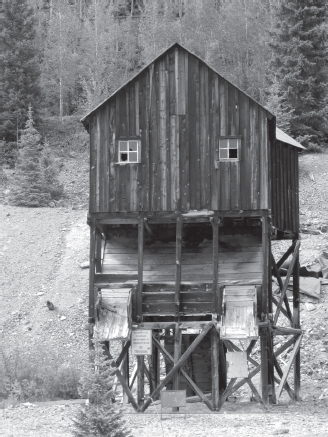

Mine structure in the Red Mountain District that produced millions of dollars in silver. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

9

SILVERTON

In 1860, a small group of prospectors led by Jim Baker ventured into the southern San Juan Mountains looking for gold. They found a little gold dust in the creeks despite the pesky black sand that clogged their gold pans. Cold weather and snow drove them from the camp they called Baker’s Park, and no white men ventured into the San Juan Mountains for the next decade.

In 1870, a few prospectors returned with some knowledge of geology, and now they knew that the pesky black sand was silver. The gold dust in the creeks came from veins in hard rock that were high above. Looking for the gold sources, they climbed the peaks around Baker’s Park, going above the tree line to twelve thousand feet in altitude. Here, three prospectors discovered silver deposits and a wide vein of gold. They began mining, and news of their discovery spread fast.

Prospecting was impossible during the winter, but in the spring of 1871, prospectors found some exposed cliffs and rocky peaks crisscrossed by wide bands of silver. As more prospectors trespassed on the Utes’ territory in the San Juan Mountains, the Indians attacked them. By the end of 1872, there was real trouble brewing. Negotiations began between the two factions, and after weeks of discussions and arguments, the Brunot Agreement was made in September 1873. The Utes gave up the San Juans, including all of the mining areas and lands surrounding the mountains. They kept some land on the west side of the Rockies as a reservation for the Northern Utes while others went to a reservation in the southwest corner of the territory. The Brunot Agreement opened the mineral-rich San Juan Mountains to mining and brought hundreds of prospectors to look for wealth on the rugged peaks. Between 1870 and 1874, 80 percent of all claims filed in the San Juan Mountains were for silver—not gold.

Mine structure in the Red Mountain District that produced millions of dollars in silver. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

In 1872, a town site was laid out in the valley, and the streets were named after the area’s first prospectors. The town may have gotten its name when a prospector joked, “We may not have gold, but we’ve got silver by the ton!” Free lots were offered to anyone who would put up a “respectable building” in the new town of “Silverton,” as ragged tents and brush shelters were slowly replaced by a rough log cabins. As more strikes were made, mining camps developed at the mouths of gulches that led up to the high peaks.

In 1874, the legislature created San Juan County and named Silverton the county seat. The summer of 1875 saw Silverton’s first newspaper, the La Plata Miner, roll off the press. This was a victory for editor John Curry, who had packed his old 1839 printing press on a pack mule and walked sixty miles over steep Stony Pass, carrying his printing supplies. There was plenty of news in this booming town, which in just two years, had a drugstore, a meat market, two general stores, an assay office, an ore reduction works, and several saloons. In 1876, Silverton had a brass band, a baseball team, and the first fire department in the San Juans. There was no church, but the town had a grand racetrack, where there was plenty of betting.

By 1878, the only roads that led to Silverton and the larger mining camps were pack trails.

Eastern newspapers described the San Juan Mountains as “the wealthiest district in the wide west,” but this did not bring wealthy investors to develop new mines. There was no economical way to get rich gold and silver ore to the smelters, and production and transportation costs were higher than profits. By the 1880s, Otto Mears had built a system of toll roads through the mountains connecting the camps, but some were barely navigable by wagons or stagecoaches.

Silverton attracted con men, thieves, and shady ladies who worked in the brothels on Blair Street. By 1875, this had become Colorado’s most notorious red-light and gambling district with around forty saloons and dance halls and eighteen brothels. There were twenty-seven gambling dens, and one of the most popular was the Laundry, where “If you went in with any money, you came out clean!”

In 1879, the town fathers passed a number of ordnances against “bawdy houses,” prostitutes, and gambling halls. Bawdy houses were fined $50 to $300 per month, while prostitutes paid $10 to $100 per month. “Fines” were issued on schedule and paid every month by the working girls or the madam. Gambling halls were charged $25 per month. The stiff license fees paid by brothel owners, prostitutes, and dance hall girls defrayed the costs of city and county government, and Silverton’s coffers grew full. This revenue from vice made property taxes unnecessary, making the town fathers happy.

Many of Silverton’s citizens and lawmen owned large saloons and elegant bordellos, often masquerading as dance halls. They operated twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. When a dance hall or a large bordello changed hands, the occasion was celebrated with a grand ball. The affair was described in the Silverton Standard, and the article would always conclude, “The lack of space prevents us from giving the names of the Silverton elite that attended.” Naturally, the “elite” did not want their names listed as attendees of a celebration at a bordello.

These gentlemen split their social obligations between Blair Street events and the numerous activities of fraternal organizations that were promoted by their wives. The newspapers used plenty of ink describing the fraternal grand balls, picnics, and social gatherings, just as they described all the Blair Street celebrations. Brothel owners and casino operators were respected members of the Elks, Odd Fellows, Fraternal Order of the Eagles, Masons, Woodmen of the World, and the Knights of Pythias, while their wives were active in the Women of Woodcraft and Eastern Star.

Silverton’s Cowboy Band of 1880 was very popular and traveled around Colorado performing. Courtesy of History Colorado.

Silverton’s citizens were anxious for the Denver & Rio Grande to arrive and watched anxiously as the railroad survey crew worked its way up Animas Canyon in 1879. The rugged mountains and narrow, rocky gorge made their work very difficult, and the crew often to be belayed down steep cliffs. During the fall of 1881, they began building the roadbed and laying the tracks north until deep snow stopped all work. Avalanches often swept down the slopes, across the canyon, tearing up the newly laid tracks.

After the spring snows melted, work resumed, and the railroad tracks slowly approached the town. On July 13, 1882, when the first D&RG train chugged triumphantly into Silverton, it was met by two brass bands and a huge crowd. The arrival of the railroad brought less expensive food and supplies, and the cost of transporting ore to the smelters was cheaper. This brought mining investors and businessmen, whose new enterprises boosted the economy.

The bitter cold winters piled up snow burying houses so deep, that people made trapdoors in their roofs so they could get inside. In 1884, heavy snow drifts and an avalanche blocked the railroad tracks and isolated the town for seventy-three days. Crews from Durango and Silverton, using picks, shovels, and dynamite, worked for days to break an opening in the eighty-four-foot-thick wall of compacted snow and ice blocking the canyon. When the train finally came whistling into town, it was met by a weeping, cheering crowd, who’d been facing starvation. Their shared food was gone, and there were only a few cups of flour left.

During the Silver Decade of the 1880s, Colorado became the nation’s number-one silver producer, more than $14 million a year. Between 1890 to 1893, silver production increased to $20 million per year, but the “silvery San Juans” became victims of their own success. For several years, the government had been purchasing silver, which maintained its price. When they produced more silver than the market could absorb, prices gradually fell. After Congress repealed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1893, the price of silver collapsed, mines closed and the Silver Kings, who’d ridden the silver wave to wealth and prominence, were ruined. Jobs were lost, foreclosures began, property values fell, savings disappeared as banks and businesses failed. Without the mines, the railroads couldn’t pay their debts, and coal mining dwindled. As Silverton’s mines closed, 1000 men were thrown out of work, and many left town to look for work elsewhere.

Silverton’s economy improved during World War I since many gold and silver mines also produced lead, zinc, and strategic metals. The soldiers were coming home from the war when the Spanish influenza struck in October 1918 and wiped out entire families in one day. There were so many deaths that the undertaker was overwhelmed, and bodies stacked up outside the mortuary. In a mass grave in Hillside Cemetery, 100 victims were buried, and a memorial marker commemorates this tragic time. Spanish influenza hit Silverton hard, and in just three weeks, 152 people died; that’s twelve percent of the population. Silverton lost the greatest percentage of its citizens to Spanish influenza of any other town in the United States.

Hard times lasted until World War II, when many mines resumed operation, producing gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, tungsten, and manganese. Then in the 1950s, the boom-and-bust cycle returned as many of the larger mines that had survived for years shut down for good. Mining was at a low in Silverton, and the town barely hung on.

Today Silverton’s year-round population of 500 is supported by tourism, instead of mining, and the railroad is as important as it was a century ago. Instead of carrying gold and silver from the mines, now 200,000 visitors take the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad to this mining town every year.

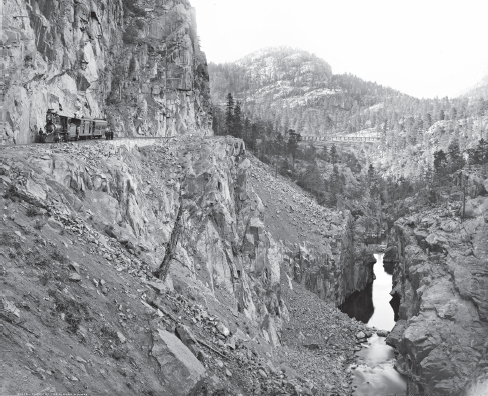

Denver & Rio Grande engine on narrow-gauge tracks high above the Animas River. Courtesy of History Colorado–William Henry Jackson Collection.

GRAND IMPERIAL HOTEL

Built by a ladies’ corset manufacturer from England, the Grand Hotel opened on July 3, 1883, to a huge celebration. The three-story brick building had been planned for businesses and apartments, but the owner, William Thomson, listened to the local clamor for a fine hotel and converted the third-floor apartments into hotel rooms. There was a large ballroom, and guests enjoyed midnight feasts in the hotel’s wood-paneled dining room, illuminated by imported crystal chandeliers. Drinks were served at the saloon’s hand-carved, cherry wood bar, with its three French diamond dust mirrors in the matching back bar.

The hotel was across the street from Silverton’s oldest bordello-saloon, built in 1875 by Jane Bowman. A London girl, she christened her brothel Westminster Hall and oversaw the construction of a tunnel that ran underneath the street to the hotel.

One of the first shootings at the hotel occurred in July 1885 when a robber broke into the hardware store on the first floor and was killed by the town marshal. There was more gunfire in April 1900 when Jack Turner found out that his lady love, Blanche, a working girl from Blair Street, was having a drink at the saloon with another Jack, a miner named Jack Lambert. He rushed to the Grand and began shooting at the couple seated at the bar, hitting Lambert twice. Blanche was unscathed, but bullets were flying as customers scrambled for cover: one pulled the faro table over on top of himself, another tried to climb a water pipe, a third hid under the poker table, while a fourth crawled under the wine room door and jumped out a window. The sheriff arrested Turner and hauled him off to jail. Lambert recovered from his wounds—and was divorced by his wife.

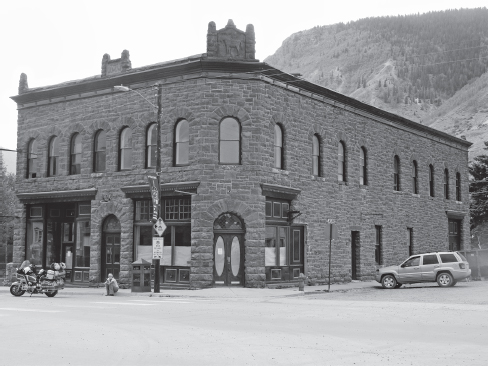

The Grand Imperial Hotel, opened in 1883, was Silverton’s largest building and first fine hotel. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

On September 3, 1904, about 1:00 a.m., a masked man burst through the saloon’s front door yelling, “Hands up!” He was waving a pistol and shotgun around when the manager grabbed the gunman’s arm, attempting to get his weapon. As the two struggled, the robber fired, striking the manager in the chest and leg. Everyone ducked for cover as the bullets flew. The bartender was hit in the arm, and John Loftus, a young miner standing at the bar, was shot in the abdomen and fell to the floor, mortally wounded. His last words were, “My God, I’m done for!” The wounded manager staggered out the door and collapsed in the street as the gunman escaped out a back window. The sheriff quickly organized a search, and the murderer was found dead in an alley, a suicide. He was identified as an “honest and trustworthy fellow” who’d accumulated huge gambling debts. The manager and bartender recovered, but John Loftus, just twenty-nine, was buried in Silverton’s cemetery.

This antique hand-carved Brunswick bar has a bullet hole, a reminder of numerous shootings in the saloon. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

The saloon was robbed several times as thieves cleaned out the safe and grabbed all the cash from the roulette and faro games. On April 17, 1907, about 3:00 a.m., three masked men strode in the door and commanded, “Throw up your hands!” The robbers were all heavily armed, each with at least one revolver and a sawed-off shotgun. They herded the thirty customers against the wall and swept the money from the gaming tables into ore bags. They emptied out the cash register and went behind the bar where the safe was wide open. Grabbing a money bag containing $1,000 in silver and currency, they raced out the back door with approximately $3,000.

Everyone knew the safe was never locked except the new bartender. When he closed the saloon on his first night, he tossed the money bag in, shut the door, and twirled the dial, locking it tight. The next morning, the safe couldn’t be opened because no one knew the combination. This fiasco concluded days later when a safecracker imported from Denver successfully used his skills on the safe.

The hotel weathered several ownership transfers, and the name was changed to the Grand Imperial Hotel in 1909. The robberies continued until the owner finally decided to lock the safe. In 1916, Colorado became a “dry state,” four years ahead of national Prohibition, and overnight, the rowdy saloon was transformed into a pool hall, serving soda pop and sarsaparilla. Prohibition hurt the hotel, which closed its restaurant around 1919 and the saloon the following year. During the hard times of the Depression, the mines shut down, and the Miners’ Union Hospital closed because it had no money. Then the Grand Imperial Hotel closed.

The hotel’s accumulated property taxes were paid in 1921 by Henry Frecker, who was issued a tax deed for the property three years later, according to Colorado law. He leased the hotel to Rosa Stewart, who reopened in 1925 and kept it going by taking boarders. One of Rosa’s tenants, fifty-nine-year-old John Zink, became infatuated with her. One day, they had an argument and a furious Zink whipped out his revolver and shot at Rosa point-blank. Luckily, his aim was bad, and he only hit her in the arm and the side. Then he turned the gun on himself, firing one shot into his head. Zink died on the spot, and after Rosa recovered, she left town.

Henry Frecker took over the management and remained at the hotel until his death in February 1944. He willed the hotel to his daughter, Edna Frecker, who was very surprised to learn of her inheritance. Forty years earlier, Frecker had abandoned his family in Victor, Colorado, and disappeared. He was assumed dead. Surprisingly, Frecker had been in Silverton since 1905 and had acquired a mine, which he eventually sold for a large profit. He saved his money and was regarded around town as a tightwad. He bought the Grand Imperial at a bargain price.

Like her father, Edna Frecker wasn’t popular, and she was especially disliked by the men of Silverton. She campaigned relentlessly against vice and sin and was determined to close the saloons, dance halls, and brothels. The town fathers breathed a sigh of relief in 1950 when Edna sold the hotel to a wealthy Texan. He went bankrupt after an expensive hotel renovation, and the heating oil supplier found himself the owner of the Grand Imperial as payment of his bill. He sold it to the Broadmoor Hotel of Colorado Springs, who owned it for eighteen years. The hotel has been through several more ownership changes and subsequent renovations.

GHOSTS

The hotel’s most well-known ghost is Luigi Regalia, a physician who’d come from Italy around 1880. He established a practice and made many friends, but after a failed romance, he sank into gloom and dark despair. On November 1, 1890, Luigi rented room 28, locked his door, and wrote a farewell letter to a friend. Then he picked up his revolver, and holding a small pocket mirror, he put the gun to his head and pulled the trigger. A physician friend and the desk clerk found Luigi lying in a pool of blood, the revolver grasped in his hand. Despite a large hole in his head, Luigi was still breathing. A second physician came, and the two doctors struggled to keep the poor man from dying, but their efforts were futile. About 2:30 a.m. on November 2, 1890, Luigi Regalia breathed his last. He was buried in Hillside Cemetery, mourned by his numerous friends.

Sometime later, a traveling salesman staying at the hotel was awakened by a sound and startled to see a dark figure in a black coat and hat standing near his bed. He described a man with a black, bushy moustache and eyes that were agonized and full of pain. The salesman was terrified, as the shadowy figure slowly approached with his hand outstretched, pleading. He whispered something, and then suddenly he was gone. The salesman jumped out of bed and ran down the stairs to tell the desk clerk. “Oh, you saw Luigi!” she exclaimed and told him the tragic story of Luigi Regalia.

This melancholy spirit is well known around the Grand Imperial, and he has been seen by both guests and employees. He makes his rounds at night, a wispy figure drifting from room to room, and some guests have awakened to see a dark shadow leaning over their bed. One woman said, “I didn’t believe in ghosts until I stayed here.…I woke up to a man with a top hat leaning over my bed in the middle of the night. I had no idea this place was haunted until the next morning when I told the staff. They just smiled and said, ‘That’s Luigi.’”

One former owner told ghost writer Anthony Garcez that Dr. Luigi has often been seen in room 314. Some guests have answered a knock on the door to find a stranger, who introduced himself as a doctor, inquired about their health, then left. Guests have commented on this ghost’s life-like appearance and professional demeanor.

There have been several renovations and re-numbering of rooms, so no one is sure where Luigi died. Some employees and guests have seen a strange tableau of a man lying on the bed while a woman in a Victorian dress bends over him. She paces frantically around the room before returning to the bedside as the scene slowly fades away.

This portrait of Lillian Russell in the lobby dates to the hotel’s early days. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

Upstairs, doors open and close on their own, startling guests. One man was lying in bed when his room door opened. He went to the door; no one was there, and the hall was empty. He returned to bed, and the door opened again. No one was there. This happened several times, and the man was ready to move to a different room when the activity stopped. Sometimes a flowery fragrance or the scent of spicy men’s cologne is noticed in the halls, and many have heard the sound of heavy footsteps. Employees report hearing footsteps approach a guest room where they’re working; then the sound stops, and no one is around. Housekeepers complain that they often feel uncomfortable, like they’re being watched while they work.

Loud banging is sometimes heard coming from the kitchen at night. The blame is often laid on the spirit of George Foster, who worked in the kitchen and was killed by an avalanche in February 1900. Occasionally a thin, scruffy-looking miner walks up to the saloon’s bar and asks for a drink. As the bartender turns to make it, his customer vanishes. A paranormal group, called Haunted Dimensions, spent some time investigating the hotel and identified Luigi’s spirit and sixteen other entities. They became aware of various apparitions in the saloon where several people have been killed. The investigators said that this was the most haunted part of the hotel.

The desk clerk said pens and papers are occasionally moved around, and that dragging sounds are heard overhead, like furniture being moved about. This happens after the rooms have been cleaned, when no one is working upstairs. Lights flicker on and off randomly in the halls and rooms, and the updated electrical system can’t be responsible. The ghostly figure of a man has been seen in the lobby, where photographers have obtained some unusual photos of orbs and shadowy shapes.

WYMAN HOTEL

Louis Wyman was thirteen years old when he stowed away on a German ship bound for New York. When the ship docked, he sneaked off and raced down an alley to start a new life with forty-eight cents in his pocket. He could say “yes” and “no” in English and worked at any job he could get. Deciding he’d like to become a cowboy, he headed for the New Mexico Territory in 1874 and was hired as a ranch hand. After about a year, he’d learned a lot about cows, horses, burros, and mules. He’d heard they were shoveling up silver in the streets of Silverton, so he decided to head for Colorado. He owned his horse, and his English was greatly improved.

Wyman was caught in a snowstorm near Raton Pass on the Colorado-New Mexico border and found shelter with “Uncle Dick” Wooten. A mountain man–entrepreneur, Wooten had widened the rugged trail over Raton Pass so trade wagons could pass, and he charged a toll. Louis worked for his room and board at Wooten’s ranch until early summer and then left for Colorado.

Louis made it through the mountains to Silverton, where he tried prospecting but did not have any luck and decided to look for other ways to make a living. He worked in a restaurant, hoping to learn to cook, but spent most of his time washing dishes. He earned his U.S. citizenship and changed his last name to “Wyman.” He decided he might have a future in the freighting business, hauling supplies to the mines in the mountains. Louis learned how to pack goods on burros and mules as he continued to plan and wash dishes.

Wyman saved his money and bought a small string of burros. They were surefooted on the mountain trails and were much cheaper to feed because they ate the wild grasses and didn’t need hay and grain like mules or horses. He contracted to haul mining supplies, food, and equipment to the mines scattered through the San Juan Mountains. Returning from the mines, the burros were loaded with bags of silver ore headed for the smelter. Wyman acquired more pack animals and a wagon, and by 1887, he was operating the largest freighting business in the area. He eventually acquired a building at the edge of Silverton as headquarters for his freighting business and stables for his animals.

The Denver & Rio Grande Railroad had arrived in 1882 and was bringing supplies and equipment from Durango and hauling silver ore to the smelters. The railroad could offer much cheaper rates than Wyman or the other freighters. Some mine owners had built a series of aerial trams using thick wire cables to carry ore in large buckets down from mines perched thousands of feet above. The cables ran in an endless loop and could haul supplies up to the mines. Miners often hitched a ride up or down in the large ore buckets of the tram. One miner described swaying along in an ore bucket as it dropped thousands of feet down a deep canyon as “producing a creepy feeling to the stoutest heart!”

Freight wagons pulled by six-horse teams were still needed to haul the heaviest or largest pieces of equipment, like boilers or compressors, to the mines, but Wyman could see that the freighting business was declining. In 1900, he sold his entire business to the British government. Wyman loaded up his mules, pack saddles, six horse teams and wagons, all the tools, and even spare horseshoes. He took everything east to St. Louis and loaded the animals and goods on barges, and then they floated down the river to New Orleans. There the animals and goods were put on an ocean freighter and taken to South Africa, where they would carry supplies to the British army in the Boer War. Wyman felt some of pangs of regret as he saw his life’s work and several four-legged friends, who’d been with him for years, leaving on that freighter.

Returning to Silverton, Wyman tore down his freighting headquarters on Greene Street and built the red sandstone Wyman Building. He carved the images of his favorite pack mules into two large pieces of sandstone and placed them on top of his new building. These monuments to the animals that were so important in his success are still there today.

Louis Wyman carved the images of his favorite pack mules in the slabs of sandstone displayed on the Wyman Building. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

Silverton needed a community building for the fraternal organizations’ meetings, dances and social events. The ladies’ clubs, sewing circles, and church groups needed space, too. The new building had a large ballroom, meeting areas, a spacious banquet hall, and a lounge for the ladies. There was indoor plumbing, and the entire first floor was comfortably furnished. Offices on the second floor were rented by doctors, dentists, and mining companies. Several small businesses and the electric light company rented space in the building for years.

In 1911, a friend of Louis’s bought an automobile in Denver and wanted to bring it to Silverton, but there were no roads that the car could navigate. The men worked out a plan so Louis’s friend and another acquaintance, who was a magazine writer, probably sensing a story, drove the car from Denver to Del Norte. Then they plowed as far as possible up the rough Rio Grande Valley toward the river’s headwaters near the beginning of Stony Pass where they met Louis.

The auto, a Croxton-Keeton, was vigorously cranked until it sputtered, then caught, started, and settled into a reassuring rumble. Off they went. The car got across the shallow Rio Grande River and then began the steep climb up the mountain. They struggled along in deep ruts, avoiding rocks and trying to protect the undercarriage. They blew out a tire, and after finally getting it changed, the men used a hand pump to inflate it with ninety pounds of air pressure. Exhausted, they crossed the Rio Grande thirteen more times, trying to avoid the river’s numerous boulders. These crossings would not have been a problem for a pack train, but after each crossing, the car crawled out of the river like a tired old turtle. As they slowly approached the summit of Stony Pass, creeping around sharp switchbacks, the tires squealed over slippery rocks as the radiator sent up jets of steam. The car was chuffing and coughing, and the carburetor barely functioned at twelve thousand feet in altitude.

The car clawed its way up the last steep grade and groaned to a stop a short distance from the top. The wheezing machine could go no further, so it was chained to a team of huge dapple grays that Wyman had arranged to have waiting nearby—just in case. The team had no trouble pulling the car over 12,500-foot-high Stony Pass. The writer snapped plenty of photos before they started downhill toward Silverton. The car’s tendency to hurtle forward like a rocket frightened everyone, and they had to stop often to cool the brakes before lurching forward again. They breathed much easier when they finally skidded around the last curve to level ground. When they drove triumphantly into town, they were greeted by a cheering crowd waving American flags, while the fire bell rang wildly. The Silverton Brass Band struck up a rousing Sousa march, and blasts of dynamite were set off from a hillside. The writer described the journey vividly in Outdoor Life magazine, and the folks in Silverton got their first look at an automobile.

The Depression brought hard times to Silverton, and as businesses failed, the Wyman Building lost its tenants. Louis remodeled the first floor to accommodate a meat market and dry goods store, but both businesses failed. Then he developed cancer in an old leg injury and died in 1924. His casket was placed on a mule-drawn sled for the short journey to Hillside Cemetery, where his many friends and business acquaintances gathered for his burial.

David Wyman, Louis’s brother, paid the taxes on the building and sold it to a friend. The first floor was converted into a warm winter garage with storage for miners working at the Mayflower Mine and Mill. This arrangement collapsed when the mine and mill closed, leaving the miners without jobs. The building went through several ownership changes and was eventually remodeled and converted into a hotel. Now this building has been included in the National Register of Historic Places.

GHOSTS

Guests and employees complain about misplaced personal items, mysterious sounds, and shadowy figures in this old building, Employees have help making beds, straightening rooms and cleaning, and some say Mrs. Wyman’s spirit is making sure the hotel runs smoothly.

The Wyman trolley picks up passengers at the railroad depot and brings them to the hotel. Courtesy of Wendy Williams.

The shadowy shape of a woman has been seen in the upstairs hall, and she’s usually carrying a bundle of towels or sheets. A previous owner told an investigator that she sometimes felt like she was being watched when she was working at the front desk. She thought this was a helpful presence and recalled instances when items and papers she’d been looking for would suddenly turn up in unusual places. The owner recalled times when she needed help with a difficult task, and miraculously, she’d suddenly get it done, “As if I had someone helping me!”