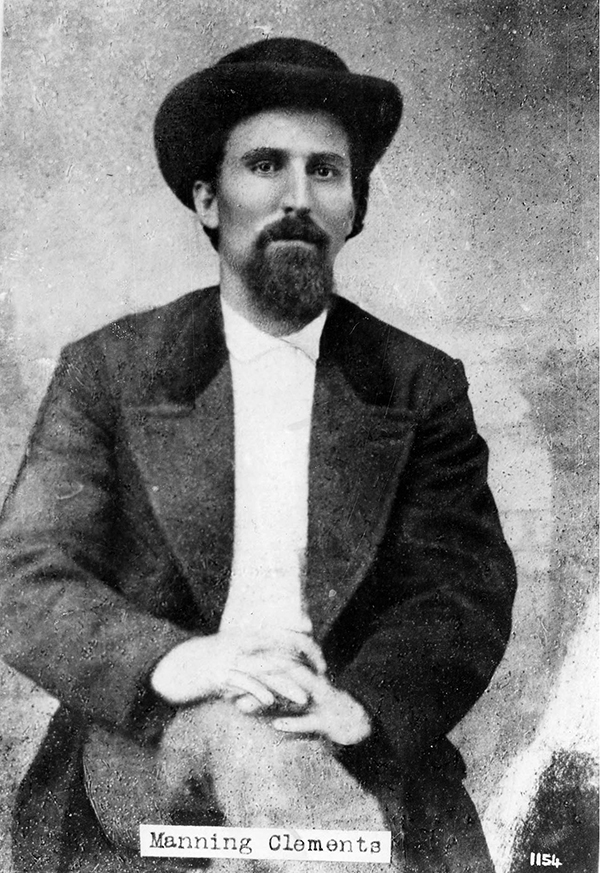

Like Father, Like Son

The Clements Family

The given name of both father and son was Emmanuel, but there ended any resemblance to things heavenly. The father, generally known as Mannen, was raised on a ranch in a Texas backwater called, of all things, Smiley. Mannen early on showed an inclination to wander from the straight and narrow path of righteousness; he was suspected of rustling and other minor peccadilloes before he branched out to jail breaking in 1872.

The man he freed was, if anything, a worse thug than he was, none other than John Wesley Hardin, killer of at least twenty-one men; he said it was forty, and it may even have been more. That is, until he was ultimately ushered out of this vale of tears in El Paso by old John Selman. Hardin was Mannen’s cousin, and Clements got him out of jail even though Hardin had fought with the Taylor clan against the Taylor family, related to the Clements. In the tangled world of Texas feuds such entanglements were not unknown.

Mannen went on to prosper in the family cattle business, driving herds northward to the Kansas cow towns—with some time out along the way in jail, where his cellmates were John Ringo, Hardin, and one of the Taylor clan. That didn’t stop him from running for the office of sheriff; after all, in his part of the world nobody wanted a shrinking violet to maintain the peace.

Mannen met his end—well deserved—in Ballinger, Texas, in 1887 at the hands of Marshal Joe Townsend. Runnels County had been recently created, and Mannen’s candidacy for sheriff was opposed. Mannen was having a few in the Senate Saloon when Townsend came in, and some hard words followed. The last one was Townsend’s.

But families like the Clements didn’t vanish into the musty halls of history that easily.

Mannen’s worthy successor was his son, also called Emmanuel, but locally referred to as Mannie. In the 1890s, Mannie teamed up with his vicious cousin John Wesley Hardin and another equally vile relative, this time an in-law, Jim Miller.

Now Hardin is well known in the annals of the murdering business; his uncivilized nature was surely not due to a neglected childhood—one of the standard excuses for growing up mean—for his father was a preacher, and the Hardin family had been prominent in the history of the Texas Republic.

Sadly, whatever fine genes his relatives may have had, Hardin didn’t get any. He started turning bad at the tender age of eleven, when he stabbed another boy. He killed his first man at age fifteen. Once he reached a sort of adulthood, Hardin kept on killing here and there, at one point hiding out with his relatives, the Clements boys.

Along the way he rode with his cousins in the bloody Sutton-Taylor feud. He was (for him) relatively quiet for a time, but in 1874 he killed a deputy sheriff, and the long-suffering state of Texas slapped a fourteen-thousand-dollar dead-or-alive reward offer on him, a considerable amount of money for the time.

He fled to Florida with his family, engaging in more or less peaceful pursuits, but in time the Texas Rangers found him even there. And so Hardin finally spent some time in a Texas prison for murder. He studied law while he was behind bars—there went another of the hackneyed excuses for outlawry . . . poor thing, he was just too stupid to get along in the world. He had married along the way, but his wife died while he was in prison, leaving him with three children.

After being paroled, he actually practiced law in Texas for a while, first in Gonzales and later in Junction. There he married again, a much younger woman who, it is said, had the good sense to leave him on their wedding day.

Hardin at last ended up in El Paso, where he spent much of his time with some kindred spirits, of which there was no shortage in the booming, violent border town. Along the way he had words with the Selmans, father and son, men as violent as Hardin was. In fact, he threatened to kill both father and son. Trouble was, the Selmans were the law in El Paso, and they were not inclined to suffer insulting hoodlums gladly.

Nor were they inclined to let chivalry get in the way of satisfaction. And so, while Hardin was shooting dice at the bar in a local saloon, Selman senior walked in behind him. Hardin was obviously having a good time, having just remarked to his companion, a grocer named Brown, “you have four sixes to beat.”

Brown didn’t have to beat anything, for about then Selman shot Hardin in the back of the head and then pumped two more rounds into him as he lay on the floor. So much for the Hollywood notion of the Code of the West. The Code of the Gunfighter worked infinitely better: no confrontations; no unnecessary risks; after all, if you took such chances, you might get hurt. Shoot ’em in the back if possible; in the back in the dark is even better.

If Hardin was a thoroughly evil man, shirttail relative Jim Miller may have been even worse, far worse. For Miller was an assassin by trade. It was his profession and probably his pleasure. If the money was right, he’d take out just about anybody; his long list of victims even included the formidable Pat Garrett—shot in the back, of course. Miller customarily dressed in funereal black suits and had considerable association with local churches when he wasn’t out killing people; hence his nickname, “Deacon Jim.”

Less flatteringly, he was also known as “killin’ Jim.” He seems to have sported an additional clothing item not customarily found on men of the cloth: a steel vest worn under his shirt, a thoughtful accoutrement that saved his life at least once.

For all his pretended piety and his long success at his trade, Miller was betrayed by his own arrogance and overconfidence. Having killed a man named Bobbitt, a leading citizen of Ada, Oklahoma, he made the simpleminded mistake of answering a wire calling him back from safety in Texas. Jim thought it was from the men who had hired him to do the murder in Ada, but it wasn’t. Though the names on it were indeed those of the men with whom he had contracted for Bobbitt’s murder, the wire was sent by the law.

And so he found himself in the Ada jail with his employers. Arrogant and boastful as ever, he ostentatiously feasted on steak sent in from the local restaurant and announced his intention to hire ace attorney Moman Pruiett for his defense. That proved to be his undoing.

For Pruiett had a phenomenal win record, a product of his great ability and, some said, a well-developed talent for trial rigging. One tale, perhaps apocryphal, tells that when one client retained him by wire, Pruiett responded that he was coming by the next train and bringing “eye-witnesses” with him. Pruiett denied the story the rest of his life, but the legend lives on.

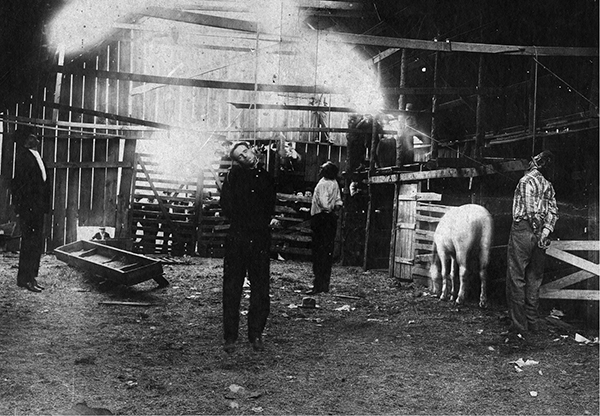

Deacon Jim Miller and friends Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library

News that the great Pruiett was on the way to defend the odious Miller was the last straw for the long-suffering people of Ada. Outraged at the thought that Miller might escape retribution for killing one of their citizens, they took immediate hands-on action.

So Deacon Jim found himself involuntarily broken out of jail along with his erstwhile employers, dragged to a nearby stable, and strung up, ad hoc, from a rafter. Jim bragged to the last; he wanted everybody to remember that he’d killed fifty-one men. Maybe he even had; it didn’t do him any good.

The good people of Ada rejoiced. The local paper commented that while lynching was ordinarily a bad thing, this one would be approved by “God and man.” If the assumption that the Almighty was on the side of the citizens was a mite presumptuous, the hanging sure played well in Ada.

And so passed another minion of the Clements clan.

His in-law Mannie Clements was not an unalloyed success as a bad man, though it wasn’t for lack of trying. He left his part of Texas when he fouled up an assassination assignment, the murder for hire of a hoodlum named Pink Taylor. He indeed took a whack at Taylor through an open window, but his shooting was lousy. He missed and killed somebody else. That made him unpopular enough that he felt a pressing need to try out new climes, in this case El Paso.

There, Mannie acquired a star, serving as a deputy sheriff and deputy constable. Now El Paso at the close of the nineteenth century was as tough a town as there ever was in the West, which is saying quite a lot. Mannie seems to have thrived on trouble, and he even got himself arrested for armed robbery in 1908. He went free, however, and the story goes that the jury cared a trifle more about their skins than about law enforcement. One healthy effect his arrest had: His career as a lawman was finished for good.

But as time wore on, Mannie turned more and more to John Barleycorn for solace and to smuggling for income. The commodity he ran across the border into the United States was, however, human. The early twentieth century saw a thriving business in running Chinese illegal immigrants from Mexico into the United States.

However good Mannie’s cash flow was from this dirty trade, in the end it proved a bad idea. It got him killed in 1908. In the Coney Island Saloon in El Paso, Mannie got into some sort of dispute with the bartender, one Joe Brown, who apparently was a competitor in the people-smuggling business. Things escalated until the two rivals went for their guns.

Mannie came in second. Like his father, he died on a dirty saloon floor.