The Plague of Cochise County

The Clanton Clan

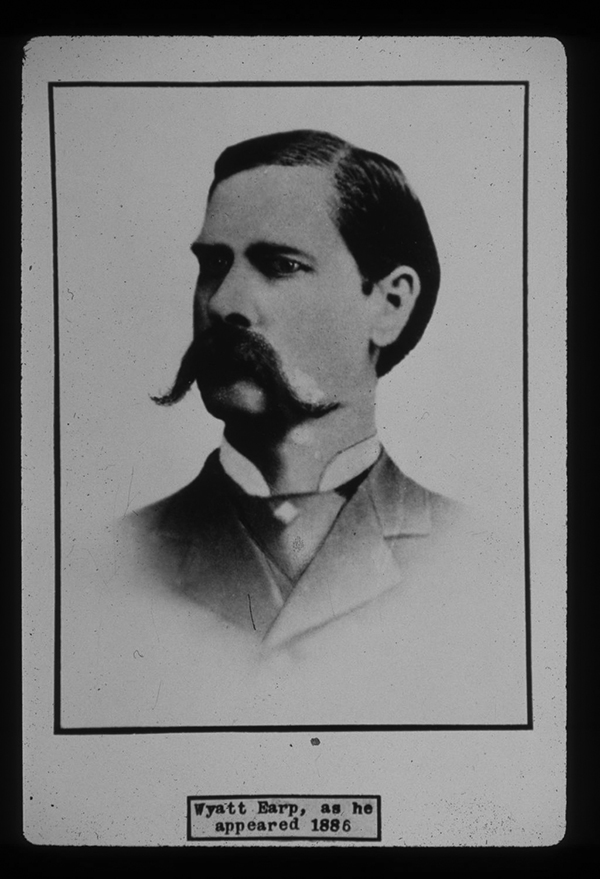

No time or place has gotten so much print or so much film as the Earp days in Tombstone. Most of it has cast the Earps in the role of the Good Guys, often without much if any regard to their human shortcomings.

Two superb recent films, Tombstone and Wyatt Earp, have stuck by the Good Guy image, although without glorifying the brothers overmuch, and at the same time giving a fair picture of Doc Holliday, especially Val Kilmer’s portrayal. Kilmer’s Holliday will ever be remembered with his classic line, delivered after Wyatt’s “single-handed” defeat of the Iron Springs ambush. Asked where Wyatt is, he replies, “down by the creek, walkin’ on water.”

The Earp brothers seldom appear in popular print—still less in the movies—as “The Fighting Pimps,” only one of the less-than-flattering names their foes and detractors gave them. And indeed, the fact is, they were men of their time, far from perfect.

So if the Earp party constituted the Good Guys—and that seems to be a fair portrayal by and large—who were the bad hombres? If Wyatt and his brothers were on the side of the angels, who were the villains of the piece?

The answer, in print as in film, is ever the Clanton clan: N. H. “Old Man” Clanton and his noxious brood. In their day, however, not everybody in Arizona subscribed to that notion. If you were part of the so-called “Cowboy faction,” your view was different.

The Clantons came to southern Arizona in 1877, where the patriarch of the family, Old Man Clanton, bought a ranch. He seems to have operated it with son Billy’s help, while sons Isaac (always “Ike”) and Phineas (“Phin,” of course) went into the freighting business. They also operated a part-time and more profitable family enterprise, regular raiding into Mexico, where there were lots of valuable cattle to be rustled.

These they peddled north of the border, and they were joined in the rustling by as unsavory a group of misfits as could possibly have collected in one place: John Ringo, Bill Brocius, Frank Leslie, Frank and Tom McLowery (sometimes McLaury), and a number of others of similarly larcenous persuasion, none of them anybody you’d want to invite home for dinner.

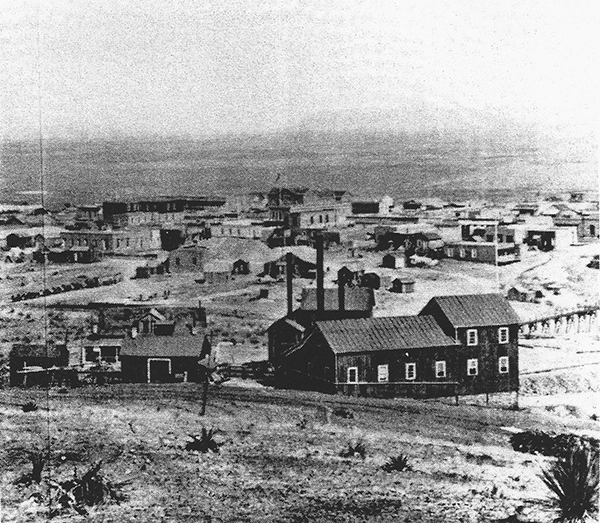

For a while, the wild town of Tombstone was their oyster, a wide-open place of twenty-four-hour merriment and considerable killing. Boot Hill was filling fast—it’s a tourist attraction these days—and the local law—in the person of Sheriff John Behan—was tolerant if not actually complicit. Since struggling small ranchers in the area grew their herds in part on the illicit traffic in beef, they tended to side with the rustlers.

Understandably, northern Mexico’s rancheros were not pleased with this wholesale rustling, nor with the murder that sometimes accompanied it. In July of 1881, for example, the Clantons waylaid a group of Mexican cowboys driving a herd through Guadalupe Canyon and are said to have murdered nineteen of them.

Tombstone, major streets 1879–80

Just a few weeks later, a band of vaqueros—or maybe it was soldados—ambushed the Clanton clan and their cowboys on the way home with a stolen herd. They blew away five of them, including Old Man Clanton himself. The shooting occurred on the American side of the border, also in Guadalupe Canyon, long the scene of considerable bloodletting.

Leadership of the clan now descended to Ike Clanton, one of the truly poisonous characters in the history of the western United States. His portrayal in Tombstone—as a bully, a criminal, and a coward—seems to be right on the money.

Once the Earp brothers appeared in Tombstone, the high-handed behavior of the Clantons and their mangy friends hit a snag. Their buddy, Sheriff John Behan, who did little or nothing to enforce the law as to the cowboys, was obviously only a talking head. The Earp boys, however, ably supported by Doc Holliday, tended to do unfriendly things like pistol-whipping noisy and recalcitrant cowboys, especially if their names were Clanton. The Earps had the support of Mayor John Clum and much of the town’s population.

After some sore heads and time in jail and similar frustrations for the Clantons and their friends, it inevitably came to open war, but exactly how that sparked is forever lost in the mists of time and the mythology that tends to grow up around any notable event in the Old West.

For what followed was the famous, deadly confrontation at Tombstone’s OK Corral—not in it as so much popular “history” has it. There are—of course—two wildly different versions of the encounter. In one, the Clantons and their friends are mostly unarmed; they don’t want to fight; they protest that they are peaceful, but in the end they are shot down mercilessly by the brutal Earp party.

In the other version, the Cowboy party spends the day bragging in the hearing of other citizens about how they’ll exterminate the Earps and Holliday. They send word to the Earps that they’re down near the corral and ready to fight, and so on. If that’s the case, then the fight that follows is entirely the Clantons’ fault. Virgil Earp summons them to surrender, holding out his gun hand in a gesture of peace and persuasion.

At the hearing before Judge Spicer, other witnesses testified to the Clanton bunch making threats to Virgil and his brothers. There were a number of witnesses who testified they saw the gunfight, or parts of it, but there was no agreement about who shot whom and when they shot them. Ike Clanton, of course, blamed everything on the Earp party and said the whole idea of the Earps was to kill him.

A woman with a clear view of the fight may have given the most compelling testimony, among other things that: “The cowboys opened fire on them, and you never saw such shooting. One of the cowboys after he had been shot three times, raised himself on his elbow and shot one of the officers and fell back dead.”

In the end, Judge Spicer exonerated the Earp party; Virgil was, after all, an officer of the law. He had every right to stop the Clanton bunch and arrest them for possessing weapons in the city, which was a clear violation of the law. Spicer’s opinion is worthy of a partial quote: “Isaac Clanton could have been killed first and easiest. If the object was to kill him, he would have been the first to fall. . . . I cannot resist firm conviction that the Earps acted wisely, discretely and providentially to secure their own self-preservation.”

Judge Spicer seems to have examined the evidence with great care, concluding among other things that the wounds to Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton could not have been received if they were in the midst of trying to surrender, as Ike loudly asserted.

The county grand jury, which could have overridden the judge’s tentative findings, chose not to. Doc and Wyatt were safe from the law, but not out of danger. The feud wasn’t over, of course. There were death threats to several citizens, including Judge Spicer.

Even the town newspapers took sides: The Epitaph supported the Earps and the decision by Spicer and the grand jury. The rival Nugget as usual took the opposing view. The small ranchers tended to support the “Cowboy faction,” while the town’s citizens welcomed the extinction of the Clanton bunch, that perpetual irritant to the public peace.

A large funeral procession and public finale for the three dead cowboys hadn’t helped cool things off at all. The remains had first been laid out for public view gussied up in new suits, under a big sign proclaiming that they had been “Murdered in the Street of Tombstone.”

The losers from the Earp-Cowboy fight Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library

Nobody will ever know precisely what happened in this the most famous of all western gunfights. The Earp version of the tale is far more persuasive, and it has considerable support from the citizen witnesses. And it’s doubly convincing for another simple reason, which the mass of writing usually tends to overlook: Only one of the Earp party had anything but a revolver.

Had a group of experienced gunfighters gone to the OK Corral intending to kill a group of probably armed enemies, surely everybody in the Earp group would have carried a shotgun, far and away the best close-range weapon ever devised. Not only is the shooter virtually certain of a hit, he can count on doing enough damage that his opponent doesn’t have the strength to shoot back.

Although the legends—both ways—will never die, the shootout is a matter of fairly straightforward history. Ike Clanton survived the fight, pleading loudly that he wasn’t armed, moving Wyatt Earp to famously declare, “The fighting has now commenced; go to fighting or get away!” Or something like that. Whereupon Ike the blowhard fled the scene, taking refuge at Camillus Fly’s nearby photography emporium.

Ike did indeed “get away,” but his brother Billy did not. One version of the battle has Billy shouting “I don’t want to fight!” and being blown away all the same by Morgan Earp. Billy had more than his share of guts: Even while wounded once and shot again, he was on his back trying to shoot at the Earps when Tombstone photographer Fly courageously ran between the warring parties and grabbed Billy’s gun from his hand.

The aftermath is fairly straightforward, continuing with the murder of Warren Earp and the crippling wounding of Virgil from ambush. The rest of the story, the “vengeance ride” of Wyatt and his friends, is better documented, with a good deal less myth and invention than the fight and its causes.

The old Cowboy faction was gone now, even John Ringo, mysteriously dead with a bullet hole in his temple and a pistol in his hand, sitting in a faraway canyon, his boots mysteriously missing, his feet wrapped in rags. He was murdered, some say, maybe by Wyatt or Doc, maybe by Johnny-behind-the-Deuce or Buckskin Frank Leslie. Or maybe somebody else. Or he shot himself. Nobody will ever know. Or care.

Phin and Ike Clanton left the Tombstone area, moving some two hundred miles north to Apache County. There they went to ranching, but old habits die hard, and they couldn’t seem to keep their hands off other people’s stock. And so, in the summer of 1887, they were faced by a stock detective and his posse. Phin wisely surrendered, and he would get ten years’ hard time. But the poisonous Ike either went for his gun or tried to flee or both. It was a bad idea, whatever it was, and the world was finally rid of him.

Whatever the true sequence of events was before and during the fabled gunfight, it seems certain at least that it would not have happened without Ike.

Not much of an epitaph.