The Kansas Horror

The Bloody Benders

In the years just after the Civil War, the so-called Western Movement accelerated as great waves of people headed west, as the saying went, “to seek their fortune.” Many of them were new immigrants, looking for a better life in this new land of promise. A man could settle on a piece of land and make it his own, no landlord, no crop sharing, no kaiser, no czar, no duke or whoever, nobody to tell a man what to do.

To the waves of pilgrims from the settled East of the United States and the hungry newcomers from across the wide ocean were added many people from the defeated South, leaving a ruined, defeated land for a new start. One hundred sixty acres of their very own just for the “proving-up” was a glowing dream to most of the families moving west.

Most of these people were solid citizens, the salt the western earth was hungry for, willing to work any number of hours in all kinds of weather to build something for themselves, something to have and to hold, something of value to leave to their children. Most of them were devout people, people who wanted to live in peace and follow the law, divine and terrestrial. They were the ideal material to build a great nation.

But there were the others. Along with the good, God-fearing people came the criminal scum, not interested in hard work, or for that matter in work of any kind. Many were fugitives from prosecution or from jail in distant parts. What all of them came west for, besides refuge from the law, was a consuming interest in what they could take away from people who worked for it, and sometimes in simply gratifying their own egos by brutalizing others.

But the Bender family was different. They were “spiritualists” for one thing, and over time the four family members exuded an aura of intense evil not common even in the tough, wild land west of the Mississippi. Their crimes were plain enough, murder and larceny; it was the rest of it that turned other people’s stomachs.

The Bender family’s lives otherwise remain a profound mystery. In the first place, it is unclear whether they were in fact a family at all. The patriarch was a hulking, unsociable brute of a man—somebody described him as “like a gorilla.” He spoke a gutteral, virtually indecipherable variety of what in those days was called Low German.

Referred to as “beetle-browed John” and otherwise known as Pa Bender, he was perhaps sixty years old. His dumpy wife, inevitably “Ma,” was somewhat younger, maybe fifty-five, so unsociable and withdrawn that some folks called her the “she-devil.” Ma Bender declared herself to be psychic; she spoke to the spirits, she said, and maybe she thought she did, given what happened later on. One neighbor put it neatly: “We thought Mr. Bender was an ugly cuss, but she’s no improvement.”

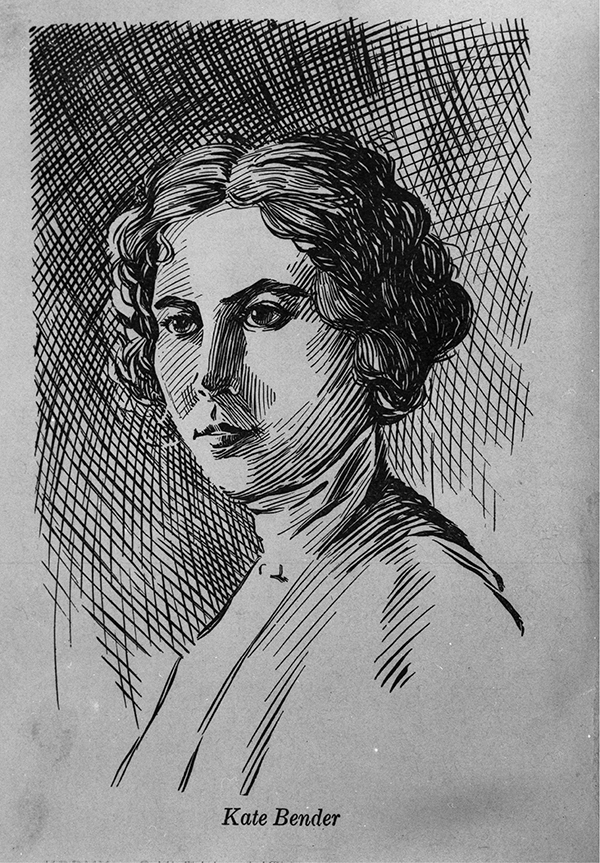

There were two children—or at least they were believed and held out to be children—son John and daughter Kate. John was given to oft-repeated spasms of giggling, which led some people to think, as one author quaintly put it, he was “a few bricks shy of a full load,” but Kate was much admired, being called beautiful and voluptuous among other good things. She was also, it appears, something of a flirt, but she had her darker side—much darker, as will appear.

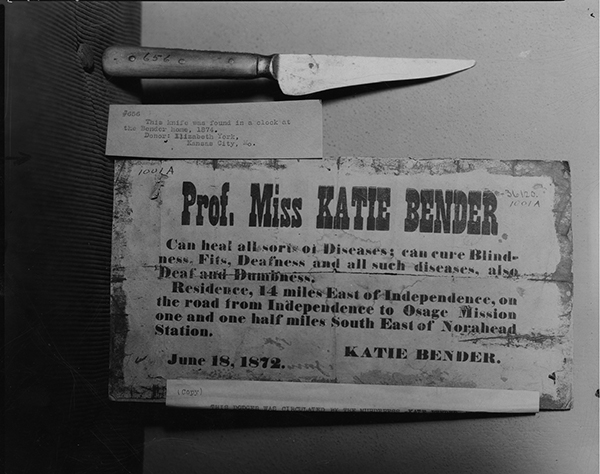

Like her sullen mother the lovely Kate also boasted of her prowess in talking to spirits, even devising a handbill calling herself, rather grandly, Prof. Miss Katie Bender, and advertising her ability to “heal all sort of diseases; can cure Blindness, Fits, Deafness . . . also Deaf and Dumbness . . .” She is said to have journeyed to small settlements round about to demonstrate her clairvoyant powers, “curing” the sick and holding séances with a variety of spirits.

In short, the whole family was a spooky lot, including the much-admired Kate. But then, people lived much farther apart in those pioneer days, and it took longer to get to know even your neighbors at all well. Today, when all the evidence is in that ever will be, there is some evidence that the Benders were not a family at all.

Pa Bender may have been born Flickinger. Ma, it is said, was named Almira Meik; she had been married earlier to one Griffith and produced twelve children, one of whom was Kate. There is also a tale that Ma had been married a number of times before Pa, and that each of her prior spouses “died of head wounds.” Giggling John, says another story, may have been Kate’s lover or husband.

The men filed on adjoining homesteads in what would later become Labette County, Kansas. The area was very sparsely peopled when the two male Benders arrived in the autumn of 1870; it had been much fought over by frontier guerrillas. In the words of one early resident, the area had been “made perfectly desolate” by the year the Civil War ended. But now eager pilgrims were coming in ever-mounting numbers.

Pa and John settled two adjoining parcels of 160 acres each, one of which was a long, narrow strip running beside the Osage Trail, which led from Independence, Missouri, northeast to St. Paul. It was regularly used by travelers of all kinds, and that was probably its attraction. The Bender men built a sixteen-by-twenty-one-foot single-room house by the road, complete with a tiny basement about seven feet wide.

The basement could be entered by either a trapdoor in the house floor or either of two exterior doors, which seem always to have been locked. There was also a sort of tunnel, which may have been used to lever in a monstrous seven-foot slab of rock, which became the cellar floor . . . or maybe it had other uses, too.

The house was to serve as the family dwelling. It would also do further duty as a sort of primitive country-store-cum-bed-and-breakfast, advertised by a crude sign that read “Grocry” until Kate turned the sign over and neatly spelled “Groceries” correctly. The Bender womenfolk arrived some time in the winter of 1871, and their crude hostel was soon open for business. Kate spent some time waiting tables at the restaurant in a hotel in newly minted Cherryvale. That there were then two hotels in that nearby town by December of 1873 is some indication of the increasing traffic on the Osage track. She apparently held the job only a few weeks, until the spirit moved—literally—to start her career as a spiritualist and healer.

So far, although the senior Benders won no popularity contests, at least Pa was known to spend some time reading his German Bible—You can’t be all bad if you read the Good Book—and Kate and Young John attended Sunday school. But a little at a time the initial good, or at least neutral, impression began to change.

Kate was accused of larceny of a sidesaddle left with her by a woman who used it to secure Kate’s healing fee. And a man—probably well in his cups—told a tale of seeing Kate and another woman dancing naked by firelight to strange music. In another report, when a doctor interrupted a Bender healing session with his patient, he was disturbed by the anger he saw in Kate’s face.

Kate’s spiritualist ad Kansas History

Right up there with the naked dancing in the theater of the bizarre was another woman’s description of her last visit to the Bender homestead, of witnessing there the Bender men plunging knives into pictures of men drawn on the house walls. That memorably unpleasant evening ended when Kate confided that the spirits told her to kill her visitor, who fled into the night. Consistent with that tale is the story of someone who saw satanic images and figurines in the Bender shack.

Then began the time of the disappearances. During the terrible winter of 1872, two men turned up with their throats cut and their skulls fractured. Later that year a man named John Boyle disappeared after he set out to buy some land, and he was carrying almost $1,900 to finance his real estate transactions.

On and on those and other unsettling stories continued to circulate in the Cherryvale area of Labette County, rumors of travelers disappearing without a trace. As early as the autumn of 1869, one Joe Sowers had set out for Kansas and simply vanished. So did a man called Jones somewhat later. He later turned up, what was left of him, in a water hole, with a smashed skull and his throat cut all the way across.

And then there was the fop in the chinchilla coat who stopped in at the Benders’ place for a drink, the man who drove up in a fine new wagon pulled by two matched horses, and Billy Crotty, who was carrying more than two thousand dollars with him; all vanished. The worst tragedy was George Lonchar, who had lost his wife and was taking his little daughter to stay temporarily with her grandparents; both gone.

Even men of the cloth were not immune, such as Father Paul Ponzilione, scared away from Benders’ “Inn” after he saw Pa Bender with a hammer whispering conspiratorially with Kate. And then there was William Pickering, a well-dressed traveler who wanted toast instead of corn bread; he also elected to sit on the side of the table away from the canvas curtain used to separate the dining area from the living quarters, and which he saw had several greasy spots at about head level.

An argument with Kate followed, and at last Pickering announced that if he couldn’t eat on the clean side of the table, he wouldn’t eat there at all. At which Kate pulled a knife on him, and Pickering departed in some haste. What finally revealed the Bender’s reign of terror was the disappearance of Dr. William York, from whom Lonchar had bought a team and wagon before he disappeared with his daughter. When Dr. York heard about the disappearance of Lonchar and his little girl, he rode down to aid in the search. When a half-starved team was found abandoned, he identified the famished horses as those he had sold to Lonchar.

And then the doctor was suddenly gone, too, vanished like the others. There was some indication that he had stopped for the night at the Benders’, and he was known to have been carrying several hundred dollars and riding a fine horse. In light of what the neighbors later learned, his possessions and his interest in the Lonchar family were a certain death warrant.

Dr. York’s disappearance brought in Nemesis at last. Dr. York’s brother, a very tough soldier, Colonel Alexander York rode out to find out what happened to his brother. He brought along still another brother, Ed York, and the persistence of the two spelled the end for the Benders’ comfortable life of murder and robbery. The brothers dug so deeply that the Benders disappeared virtually overnight, telling nobody, and leaving starving stock behind them.

For the York brothers had talked to as many residents as they could find, and they had even hired local help to drag waterways and beat their way through thick brush. With a crew that one writer estimated at fifty helpers, the brothers covered a lot of ground, and they didn’t look like they’d be stopping anytime soon.

They had interviewed the Benders and had gone away profoundly underwhelmed. The giggling son had invented a fable about himself, a tale about being ambushed and shot at; he even led the brothers to the alleged site of the shooting. The second act had been Kate’s boasting about her prowess as a healer and seer. Neither sibling impressed the investigators in the slightest, and it was a given that the older Benders would have created a very bad impression.

No doubt the vexing investigation by the York brothers provided part of the impetus, but what probably told the Benders that the game was up was a mass meeting of local men that resolved that all the residents ought to open their farms to a search. It was apparently unanimously approved, and so the handwriting was on the wall.

The news of the Benders’ sudden flight brought neighbors out in force. Once it was certain that the Benders had vanished from their shack, a thorough search was launched. It was not long before a sharp set of eyes spotted a depression in the earth in one of the few small areas ever cultivated by the Benders. The searchers began to probe, and very shortly they uncovered the body of the colonel’s brother, buried facedown in a shallow grave.

Nobody could forget the mysterious series of disappearances that had plagued this end of Labette County; now that one body had turned up and there were solid suspects, digging on a larger scale began immediately. Very soon large groups of citizens were turning over the earth near the Bender shanty, shoveling grimly in a stench of putrefaction as they uncovered victim after victim.

How the murders had been committed came slowly to light. When the crude Bender hostel was fitted out for company, a canvas curtain or tarpaulin was hung from the ceiling to separate the minuscule “restaurant” area from the family’s tiny private space. The kitchen table sat in front of the canvas, and guests were ordinarily seated at the table with their backs to the canvas. Dinner was served by one of the Bender women, but food was not all some unfortunate guest got.

The story goes that while the guest was being entertained inside, some family member checked his wagon or horse, including his luggage or saddlebags. That gave the family some notion of the desirability of turning him into a corpse; there were always risks, they knew. Sooner or later somebody might come looking for the traveler.

Once the victim was seated at his meal, and his possessions inspected, that set the stage for the hulking Pa Bender. Once the guest was occupied and off his guard, Pa simply stepped up with one of his three hammers and caved in the diner’s skull. Maybe he sometimes struck through the canvas—there were suspicious stains on it at about the right height; or he simply stepped around it and struck his victim, or both. The grisly details remain unknown.

Then the remains were quickly shoved through the trapdoor into the basement, where one or more family members cut the man’s throat. The cellar floor was soaked with blood; the stench was overpowering, and if that were not enough, the searchers found scattered bullet holes, as if hammers and knives had not been enough to finish off some of the tougher victims.

The digging turned up one horror after another. The bodies were largely naked, and at least one had been badly cut up, as if in a fury of anger. If the sight of the corpses and the smell of putrefaction were not enough, what really turned the stomachs of the searchers was the little girl. Alone of all the victims, the little Lonchar girl had not been cut or battered, rather she had been, as the examining doctor grimly concluded, buried alive under her father.

The temper of the crowd was also not improved by the sight of much of the Bender stock, which had simply been abandoned. The family had done nothing to even marginally protect the beasts, not even turn them loose to fend for themselves. The searchers were sickened by the sight of dead animals, and by some still living that had long been deprived of food and even water.

To this day, nobody is sure of the tally of the dead. There is pretty general agreement about the bodies actually found, eleven of them, plus an assortment of body parts which could not be reassembled into a single whole. What happened to the missing pieces remains a mystery. There are any number of stories that more men were killed; one old tale established the tally of victims at “pretty near forty.” That same story has Kate sleeping with John, and “whenever she had a baby they would just knock it in the head.”

And there may be some truth in the mass of mythology that has followed the killings. One story laments a young married couple who stopped at the Benders and never left, the groom murdered and the bride raped by both John and Pa before she, too, was killed.

It seems reasonable to suppose there were more victims than were ever found. The body parts account for some of them, and considering that murdering strangers was a way of life for the bloody Benders, there is a measurable chance that today’s sophisticated electronic gear might reveal anomalies in the old Bender property that could lead to more graves.

Once it was obvious that the Benders had fled, several posses went looking for them. The governor of Kansas announced a reward of five hundred dollars a head, and another thousand dollars came from Colonel York, although the enormity of the family’s crimes probably made the money secondary to a burning urge for vengeance. There were arrests and rumors of arrests of other people, none of which came to anything.

Journalists flocked to the scene, and visitors by the hundreds went away carrying a piece of the old homestead as a treasured souvenir. As the Thayer Headlight reported, “The whole of the house, excepting the heavy framing timbers . . . and even the few trees, have been carried away by the relic hunters.”

The searches for the Benders went on. One story declares that the Benders were run down “on the prairie,” killed on the spot, Kate being singled out to be burned alive, the ancient punishment for a witch. Others said the searches found nothing, or that all four Benders were caught and hanged forthwith, without benefit of clergy.

One tale with the ring of truth relates that the Benders got away by train, their progress traced by recollections of railroad employees of their luggage, which included not only a white bundle but a “dog hide trunk,” whatever that may be. One search led across the Oklahoma border to the town of Vinita, where pursuing detectives got word of four Germans, the youngest of whom had told a local man that the four wanted to go far west to an “outlaw colony.”

The detectives seem to know of this place, a spot where fugitives lived like troglodytes in dugouts—and a place where lawmen who went in stood a very good chance of never coming out again. The search went on, and they found traces of their quarry somewhere north of El Paso. There the searchers gave it up.

There are other variations on the tale, leading to the family’s ultimate unhappiness with living in or near the “outlaw colony.” This story had Kate leaving first, bugging out with a transient painter, who later deserted her. The same tale has the old folks leaving, too, until Pa deserted Ma, taking with him the remaining loot.

Bender victims’ graves Kansas History

Other tales abound. Ma murdered three of her children, goes one such story, because they saw her murder her husband of the day. Pa was a suicide in 1884, or maybe Ma killed him in an argument over their bloody loot. Another story reports that John really was shy some bricks.

There is much, much more to the suppositions about the ultimate fate of the repulsive Benders, all of it entertaining, but far too convoluted to be included here. It has been ably explored by more than one writer, particularly Fern Morrow Wood, in The Benders: Keepers of the Devil’s Inn.

Whatever the family’s subsequent history, one would suspect that it involved a strong odor of brimstone.