The Bumbling Lawyers

Jennings & Jennings, Esq.

Clumsy Elmer McCurdy had to get killed by the law, get embalmed, and become a professional dummy to have any success in crime, but more on that later. Like Elmer, attorney Al Jennings was a considerable embarrassment to the outlaw profession. And like Elmer, he embarked on a second career with his brother Frank, also a lawyer.

Al had been infinitely more successful as a lawyer than he was as a bandit, at which he was a colossal flop. The difference was that, unlike Elmer, he didn’t have to get himself killed to change careers. Al managed to reinvent himself, producing not only reams of dubious prose but a movie glorifying his undistinguished past as a criminal.

What really set Al apart was his signal and uniform lack of success at the outlawing business. Christened Alphonso J. Jennings, he was born in 1863 back in Virginia, son of a lawyer. By 1892 his family had moved west and settled in Canadian County, Oklahoma Territory, at the town of El Reno. His father became a judge in the local court, and Al practiced law in the area with his brothers, John and Ed. In time, the family moved north to the town of Woodward.

Now in those days Territory lawyers tended to be a tough and aggressive bunch, and the Jennings boys fit right in. In due course, however, they tangled with one of the toughest of them all, Temple Houston. Houston was the son of Sam Houston, the father of Texas, and he had been both a district attorney and a state senator down in Brazoria County, in a wild panhandle judicial district. Houston was the very picture of the successful frontier lawyer, with his Prince Albert coat, ornate vest, and, of course, Colt revolver. He had also moved north to Woodward, and it was there that he locked horns with the Jennings boys.

The conflict apparently arose over some harsh words exchanged during a hard-fought case involving Houston on one side and Ed and John Jennings representing the other. Houston called brother Ed “grossly ignorant of the law”—which may have been true—whereat Ed called Houston a liar.

Both men reached for their guns, but cooler heads prevented any bloodletting there and then. Now that sort of thing was not uncommon in those rough-and-ready days, but what made the insult particularly bad this time was that after court adjourned, Houston and a sometime client—named, of all things, Love—met Ed and brother John in the Cabinet Saloon.

Predictably one thing led to another, more hard words were exchanged, and everybody started shooting. Ed ended up dead on the saloon floor, and John ran for his life, wounded in his arm and body.

Al wrote later—he wrote a lot in later life—that Ed was “ambushed.” However, several territorial newspapers published accounts of the fight that described it as no more than a common brawl, in which the Jennings brothers came in a distant second. One account reported that, at the saloon, “the quarrel was renewed. Very few words passed before all drew their pistols, including [Houston’s friend] Love. . . . All engaged in a running and dodging fight except Houston. The huge man stood up straight and emptied his revolver without twitching a muscle. . . . Neither Love nor Houston were wounded although several bullets passed through their clothes and hats.”

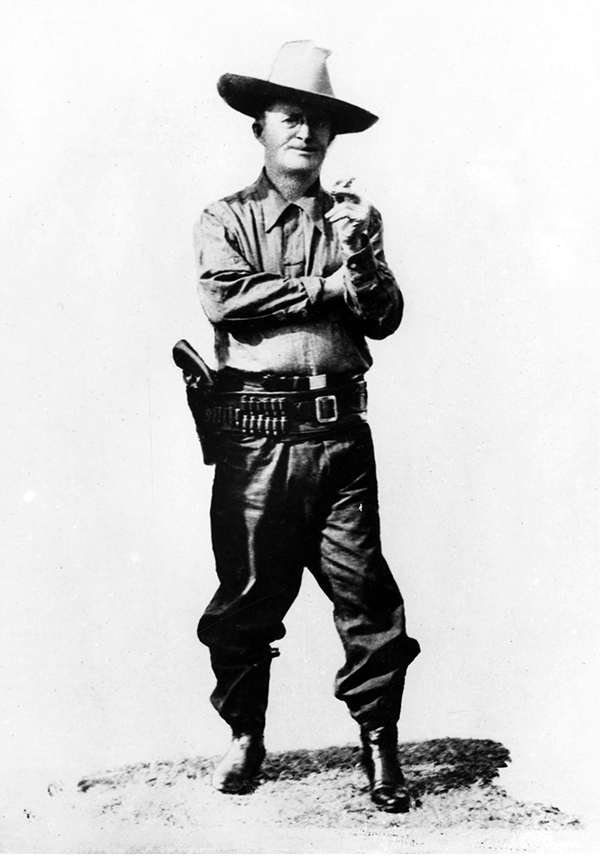

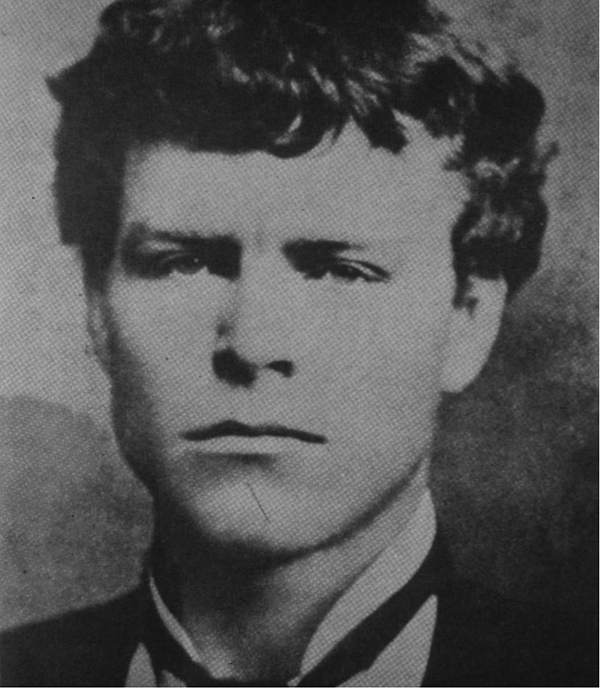

Temple Houston Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library

Al wrote that he was summoned to the saloon, where he knelt piously beside his brother’s corpse and “swore to kill the man who had murdered him.” Maybe he swore, but he sure didn’t try very hard to go seeking vengeance.

Instead, Love and Houston were tried and acquitted, after eyewitnesses said Ed Jennings went for his gun first and may have actually been shot by his own brother. In any case, Al continued to fulminate about killing Houston but continued to do nothing to carry out his dark threats. Instead, he wired another brother, Frank, in Denver, and the two went “on the scout,” as the saying went, allegedly to set up a lair from which to sally forth and kill Houston and Love. Houston and his friend weren’t hard to find, but somehow the Jennings boys couldn’t manage to be where their quarry were at the same time. Instead, the Jennings brothers launched a brief and somewhat ludicrous outlaw career.

They collected some helpers, rank amateurs Morris and Pat O’Malley, and somewhere along the way were joined by perennial Territory bad-man Little Dick West, alumnus of the Doolin gang. They may also have been assisted by Dan Clifton, another real outlaw, better known as “Dynamite Dick,” a onetime Dalton and Doolin follower.

Early in June 1897, the new gang held up a store in Violet Springs, one of the Pottawatomie County “saloon towns.” They went on to stick up another country store, robbed a “party of freighters” on the road, and then capped their spree by robbing another saloon and all the patrons. With a sackful of money and some stolen whiskey, they headed for the woods to relax and savor their success.

Robbers identified as Al and Dynamite Dick held up a post office at a wide spot in the road not far from the town of Claremore. That brought federal officers looking for them. In his dubious autobiography, Beating Back, Al said this raid was only to test out something called a “set-screw,” a contraption he said was designed to pop loose locks from safes. This robbery netted seven hundred dollars, which Al, ever boastful, said was stolen “just to pay expenses.”

It was a good beginning, since everybody in the bunch was a tyro bandit except for Little Dick and Dynamite Dick. It was also the last major run of success the gang would have, and now the law was looking for them. Chief among the searchers were Deputy US Marshals Paden Tolbert and Bud Ledbetter, experienced, smart, and tough, and very bad men to have on your back trail.

Ever hopeful, Al stopped a Santa Fe train near Edmond, a town just north of Oklahoma City. Three members of the gang had boarded the train at Ponca City, well to the north, and transferred to the tender when the train stopped for water at Edmond. The outlaws forced the train to halt a little way down the road, where four more outlaws materialized out of the darkness.

There followed much shooting and yelling to cow the crew and passengers and prevent interference with the onslaught on the express car. Bullets through the wall of the car forced the agents to open the door, and the gang entered to claim their bonanza.

So far, so good. But then things went sour when the safe refused to open. The “set-screw” was apparently left behind or maybe it proved to be unsatisfactory; so the gang tried dynamite. Not once but twice they blasted the formidable Wells Fargo safe, but it refused to open. Or maybe, according to another version of their debacle, there wasn’t a safe on that train at all. Defeated, the outlaws disappeared.

They were empty-handed from their first try at a train robbery, and they were unsuccessful at simply trying to flag another down—the engineer just waved at them. And so the gang decided that practice might just make perfect; they would try on a train again a couple of weeks later.

This time they chose Bond Switch, not far from Muskogee. The gang laboriously stacked railroad ties on the tracks as a roadblock and hunkered down in ambush to wait for their prey. The train arrived as scheduled, but the engineer, instead of using the brakes and stopping, used the throttle instead. He smashed through the barricade of ties, and the train disappeared into the night.

Unrobbed.

With the law again on their trail, the gang decided to replenish their money supply by robbing the Santa Fe train depot at Purcell, south of the town of Norman. This time they didn’t even get started, for a night watchman saw them skulking about in the gloom before they even began to rob anything. The watchman promptly alerted the station agent, who called the city marshal, who showed up with a posse.

Foiled again.

Shortly afterward, one story goes, the law learned that the gang intended to rob the bank in Minco, but the outlaws again were thwarted because a band of citizens mounted a twenty-four-hour guard on the bank. The Jennings boys and company were getting hungry.

By this time, considerable mythology surrounded the gang’s operations. Al Jennings wrote long afterward that at this point he and Frank were comparatively rich from train robberies and a bank job down in Texas. Well, maybe. Rich or not, Jennings wrote that they took a six-month trip to Honduras. There they met one William Sydney Porter, better known later as O. Henry, who would go on to write dozens of the world’s most memorable short stories. Just now, however, Porter was also on the run, facing an embezzlement rap in Texas.

Early in 1897, Porter came back to turn himself in and face the music, but Jennings, according to him anyway, returned to Texas by way of San Francisco and Mexico City. Whether Al was luxuriating in Honduras, or simply hiding out in penury, he was back with the old gang by October of 1897 and preparing to try another train holdup.

The gang chose a southbound Rock Island train they thought was carrying some ninety thousand dollars, headed for banks in Fort Worth. Al decided to stop this train in broad daylight, on the dubious thesis that the usual guards were only on duty at night. And so, on the morning of October 1 the gang—six men this time—forced a railroad section crew to stop the train. The gang hid themselves behind bandannas, except for Al, that is, who made himself a weird sort of mask out of a bearskin saddle pocket, cutting a couple of eyeholes for some minimal visibility.

Again, a good beginning, although Al’s mask slipped sometime during the holdup. And this time Al and his men had brought lots of dynamite. They were resolved not to be stopped again by a strong safe. And so they laid their charge, lit the fuse, and waited for the money. Frustrated, the bandits laid another and even heavier charge, and the whole train shook. But not the safe.

So the gang was reduced to tearing open the registered mail and robbing the train crew and the passengers—more than a hundred of them—of their cash and watches. Along the way one of the outlaws shot off a piece of ear from a passenger who was slow to cooperate, but he was the only casualty.

This unusual daylight robbery brought lawmen in swarms, several posses converging by train on the outlaws’ probable escape route. In addition, the American Express Company and the Rock Island ponied up a reward, eight hundred dollars a head for every outlaw, a good deal of money back then.

But at least the gang got away, ending up circling back to a farm near El Reno, home of a farmer well-disposed to them. There they rested and split up the loot. Moving on, in the cold weather of late October, they moved east toward the town of Cushing, and there they sought sanctuary from the chill and an infusion of money at the home of one Lee Nutter, a local merchant.

They did this simply by waking Nutter, shoving a pistol in his face, and demanding that he go to his store at the front of the building and give them his money. But there wasn’t any, for Nutter had sent his store’s receipts on to the bank in Guthrie. So the gang had to make do with a couple of weapons and a whole fifteen dollars, plus stealing a jug of whiskey and a selection of coats and such from the store’s stocks. The pièce de résistance of their loot was a bunch of bananas. It was another failure, but it was as close to a success as this inept gang would ever have again.

Dynamite Dick and Little Dick West left the gang at about this time somewhere around Tulsa, disgusted with all that work and danger and hardship for no reward. They split up, and Dynamite Dick headed in the direction of Checotah. Early one morning he rode past two deputy marshals—Hess Bussey and George Lawson, lying in ambush waiting for him to appear.

The marshals offered Dick a chance to surrender, but he was wanted for more than the gang’s amateurish crimes. There was a warrant for him for a murder committed back in his days with the Doolin gang. With nothing to lose, the outlaw whipped up his Winchester and fired. A return shot broke his arm and knocked him from the saddle, but he regained his feet and staggered into the brush, leaving his rifle behind.

The marshals followed, trailing him by spatters of blood, but the trail was hard to stick to. And then, as night fell and it seemed they had lost him completely, they came on a cabin in the woods. Nobody answered their summons to surrender, until they fired warning shots and announced that they intended to burn the cabin to the ground.

At this a woman and a boy came out. The officers twice commanded them to set fire to the cabin, and on the second command Dynamite Dick ran from the door, shooting as he came. The officers quickly put several holes in him, and he was dead within minutes.

Thus passed Dynamite Dick, veteran of dozens of outlaw forays including the fight at Ingalls in Oklahoma Territory, in which three deputy marshals died, as well as of the bank holdup and murder at Southwest City, Missouri.

Little Dick West was next. Heartily sick of the inept Jennings and his crew, West agreed to help the law entrap the gang, which was again planning to rob a gold shipment. The gang had assembled at the ranch owned by one Red Hereford, but they left at the high lope just before the marshals’ posse arrived.

Which only delayed the reckoning a little. On November 29 the gang was holed up in a ranch house owned by a Mrs. Harless. After they had eaten the evening meal, they were visited by a neighbor. He had been sent by the law to confirm the bandits’ suspected presence at the Harless place, but he was obviously nervous and somewhat unconvincingly claimed that he was lost.

Mrs. Harless didn’t believe him and the bandits took alarm, so much so that they posted Morris O’Malley as a sentry in a wagon near the barn. None of them saw the federal posse surrounding the house in the darkness. Deputy Marshals Tolbert and Ledbetter were out there in the night with five other men, simply biding their time until the house grew dark and quiet.

O’Malley wasn’t much of a guard, for Bud Ledbetter appeared out of the gloom, threw down on Kelly, and left him bound and gagged in the barn. On the morning of November 30, Mrs. Harless’s son appeared, walking out to fetch a bucket of water. He entered the barn and the officers snapped him up to join O’Malley. But when her son was missed around the family hearth, Mrs. Harless herself appeared and went into the barn. Ledbetter collared her and explained the situation.

He told her they had a warrant for Al Jennings, and he wanted her to go back inside and tell the outlaws they were surrounded. The outlaws were to come out with their hands up and surrender. If they didn’t, she and her hired girl were to leave the house at once and go to the cemetery. Mrs. Harless returned to the house and delivered her message, and Ledbetter could hear sounds as of an argument from inside. Very quickly Mrs. Harless and the girl left the house, swathed in blankets against the cold.

Jennings opened fire on the lawmen, but this time he and his men were up against the first team. Within a few minutes it dawned on them that it was high time to leave. And so they did, running out the back of the cabin, heading for an orchard, and scrambling through fire from two possemen.

They were lucky, for one officer’s rifle jammed at the first shot. A second got a charge of shot into Frank Jennings, without appreciably slowing him down. All of the bandits had been wounded, but none so crippled that they could not run at least a little way.

Al Jennings had been hit three times, including a bullet in his left thigh, but he could still move, and the bandits waded a creek and disappeared. Ledbetter was not happy, and he was even less so when the officers lost the trail and could not regain it after a long search. Taking Morris O’Malley and the gang’s horses and horse furniture with them, the posse returned to Muskogee.

The fleeing gang members got a sort of transportation when they encountered two Indian boys in a wagon and commandeered both wagon and boys. The next day, after wandering somewhat aimlessly around the countryside, they stopped at the home of Willis Brooks. The gang may have been free, but they were in sad shape otherwise. Al and Pat O’Malley, at least, needed medical attention, and so they sent Brooks into town with directions to find a doctor.

Instead, he sought out and found Bud Ledbetter and told him where the gang was hiding. That night Ledbetter, Tolbert, and two other lawmen set up an ambush in a ravine where the road passed beneath high banks. They dropped a tree across the road as a barricade and settled in to wait.

They waited most of the night until a wagon came creaking out of the gloom with Al and Pat O’Malley bedded down in the back and Frank driving, following directions from Brooks that were supposed to take them to safety in Arkansas. In fact, Brooks had sent them straight into Ledbetter’s trap. There was no fight this time. Confronted by four rifles, the outlaws gave it up and were transported to the Muskogee jail, where Morris O’Malley already languished.

Which left Little Dick West, still free, still wanted. West had friends in the Territory, so he could often find a safe place to hole up. Moreover, he had long been famous for wanting to sleep out of doors whatever the weather, someplace out in the brush away from people. He would be hard to catch.

But the law managed it, the law this time in the person of tough Deputy US Marshal Heck Thomas, who had kept order in the territory for many years, and who had killed Bill Doolin when the outlaw leader would not heed his order to surrender. If anybody could run West down, it would be Thomas.

West was now working as a farmhand between Kingfisher and Guthrie, laboring for two different farmers, Fitzgerald and Arnett. Mrs. Arnett spilled the beans when she was heard to say in Guthrie that Fitzgerald’s hired hand was trying to get her husband to commit a robbery with him. Such evil tidings quickly found their way to Heck Thomas. The man had used an alias when he hired on, but Thomas guessed from the description that he was hearing about Little Dick West.

Accordingly, on the seventh of April, Thomas led a four-man posse, including the formidable Bill Tilghman, off to the Fitzgerald farm. Fitzgerald said he didn’t know anything about the hired man, who in any event had long since left his employ. When the lawmen found a horse matching the description of West’s in Fitzgerald’s barn, the farmer said that he traded for the animal.

Unconvinced, the posse rode off toward the Arnett place, and on the way they got lucky, spotting a man “scouting along the timber to the left.” Thomas and Tilghman began to follow him, and the others rode on toward Arnett’s farm. There they saw the same man standing by a shed. The man promptly ran for it, and the three lawmen stepped into the open and ordered him to halt.

It was West, and his only response was to keep running and snap off several shots from his revolver. The lawmen responded with shotgun and rifle fire, and West was hit as he dove under the bottom strand of a barbed-wire fence. He was dead before the possemen could reach him.

Frank Jennings got five years hard time in Leavenworth; so did the O’Malleys. At that they were lucky, and Frank, at least, knew it. When he got out, Frank headed for the family home down in Oklahoma and passed from history.

There is a story that Temple Houston magnanimously offered to defend Al, an offer somewhat ungratefully refused. And so, in 1899 the court gave him a life term, but that dreadful sentence was later reduced to five years, allegedly through the able legal work of his brother John. He was out of durance vile in 1902 and received a presidential pardon five years later. Now he could start his second career, having been a notable failure at the first one.

Jennings settled in Oklahoma City in 1911, went back to practicing law, and almost immediately set his sights on political office. The next year he won nomination for county attorney of Oklahoma County on the Democratic ticket, but he lost in the general election. Nothing daunted, two years later he ran for governor, of all things, openly talking a lot about his outlaw days.

By then his life on the scout was commemorated not only by his 1913 book, Beating Back, but also by the film he made from the book, also called Beating Back. Al even starred in the movie, which at least gave him great face recognition with the voters.

It wasn’t enough. The best Al could do was place third in a field of six in the Democratic primary. That was enough for him, so Al gave up both politics and the practice of law and retired to sunny California, where he went to work telling big lies, posing for innumerable swaggering “tough guy” photos, and working as an “advisor” to people making Western outlaw films. He worked hardest at assiduously cultivating his own myth as a real bad man.

Along the way he allowed as how he’d been a buddy of Jesse James—an interesting claim, since the Woodward gunfight with Houston had been in 1895 and Jesse was dead by early 1882. But at least Al was consistent about it: The moment he laid eyes on preposterous Jesse imposter J. Frank Dalton, he crowed that he knew that there feller was Jesse for sure.

Al died in Tarzana, California, the day after Christmas 1961. He had been a monumental flop as an outlaw, but all the same, it had been quite a life.