After grounding the Decatur in the Philippines in the summer of 1908, Chester Nimitz reluctantly reported for submarine duty. His characterization of these vessels as “a cross between a Jules Verne fantasy and a humpbacked whale” was slow to change. During his first-class year at Annapolis, Nimitz and his classmates had taken training runs on the Severn River aboard the navy’s first commissioned submarine, Holland—all fifty-four feet of it—and Nimitz had not been impressed. The only good thing about duty aboard these small “boats”—submarines were never called “ships”—was that they offered plenty of command experience.

Submarines themselves were not particularly new, but neither had they progressed very far in sophistication. The egg-shaped, one-man, hand-driven Turtle tried to sink HMS Eagle, a sixty-four-gun ship of the line anchored off the tip of Manhattan during the American Revolution. Almost a century later, the Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley did in fact sink the Union sloop Housatonic in Charleston harbor after ramming it with a torpedo-tipped, harpoon-like device. The resulting concussion waves sank the Hunley, too, and its crew was lost.

For the entire nineteenth century, the navies of the world seemed to eschew submarine development out of some foreboding that doing so might disrupt the established dominance of capital surface ships. No one put this matter more succinctly early on than John Jervis, Great Britain’s first lord of the Admiralty during the Napoleonic wars. Hearing of Prime Minister William Pitt’s infatuation with an early submarine design, Jervis exclaimed, “Pitt is the greatest fool that ever existed to encourage a mode of war which those who command the sea do not want and which, if successful, will deprive them of it.”1

While upper echelons resisted submarine development, by the late 1890s Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt was among those urging the navy to take a closer look. Later, as president, Roosevelt was finally able to do something about it. On August 25, 1905, while he idled at his home, Sagamore Hill, and waited for emissaries to come to terms and end the Russo-Japanese War, Roosevelt embarked on a little diversion. Despite gray skies and choppy seas on Long Island Sound, he descended beneath the waves aboard Plunger, the U.S. Navy’s second commissioned submarine.

The experience left Roosevelt ecstatic. “Never in my life have I had… so much enjoyment in so few hours,” he wrote to his secretary of the navy three days later. But there was much more. “I have become greatly interested in submarine boats,” Roosevelt continued. “They should be developed.” As for the old guard “at Washington who absolutely decline to recognize this fact and who hamper the development of the submarine boat in every way,” the president was quick to order changes. “Worse than absurd” was his discovery that sailors risking their lives on these early craft were not accorded the usual extra pay for sea duty. The president decreed otherwise.2

So when Ensign Chester Nimitz reported for duty with the First Submarine Flotilla early in 1909, his assignment at least showed on his record as “sea duty.” He assumed command of the Plunger and came to grips with one of its basic flaws. Plunger and its sisters were powered by gasoline engines on the surface and batteries when submerged. But gasoline proved too volatile a fuel. Not only could it cause disastrous explosions, but also a boat could fill with crippling fumes even when submerged and running on batteries.

Reluctant submariner though he initially was, Nimitz was also always one to embrace the positive in any assignment and put his full energy into it. Characteristically, he assumed the role of problem solver and began a campaign to replace gasoline engines with diesels. The brainchild of the German engineer Rudolf Diesel, diesel engines, too, were in their infancy, but they relied on the heat of compression to ignite the fuel rather than an incendiary spark. (Ironically, the German navy would lag in incorporating this improvement into its own submarine fleet.)

The other recurring theme in submarine development was torpedoes. When Admiral David Farragut damned them and steamed into Mobile Bay during the Civil War, he was only ignoring free-floating and moored mines. No explosive projectiles came speeding toward him. But just after the Civil War, Englishman Robert Whitehead designed the prototype of a self-propelled torpedo powered by compressed air that could be launched underwater.

Fourteen feet long, fourteen inches in diameter, and weighing three hundred pounds, it delivered an eighteen-pound dynamite charge up to seven hundred yards at a speed of six knots. With improvements in directional control, range, speed, and explosive power, Whitehead torpedoes quickly became an offensive staple for navies around the world, albeit still fired from surface ships as the Japanese did at Port Arthur.

The same basic torpedo design was soon put aboard the early Holland-class submarines, although the Plunger and its six sisters mounted only one torpedo tube each. Bigger boats with more tubes followed, and by 1910 the American navy had commissioned eleven additional submarines of ever-increasing size, still all gasoline powered. Of these, Nimitz commanded the 105-foot Snapper, with two torpedo tubes, and the 135-foot Narwhal, which mounted four tubes. By then, Whitehead’s successors were mixing pure alcohol and water with compressed air to produce a high-pressure steam that turned a turbine connected to the propeller shaft. This improved weapon still left a telltale wake of air bubbles, but it could carry a heavier explosive payload over a much greater distance.3

By the fall of 1911, the twenty-six-year-old Nimitz, now a full lieutenant, returned from sea duty aboard the Narwhal and was ordered to the shipyard at Quincy, Massachusetts, to oversee the installation of diesel engines in Skipjack, the navy’s first diesel-powered submarine. Nimitz was to assume command after its commissioning, and he took some satisfaction in knowing that the navy had come around to his way of thinking about the older gasoline-powered boats.

But before taking Skipjack to sea, Nimitz was introduced over a bridge game to Catherine Freeman, the daughter of a ship broker. It was not necessarily love at first sight—Catherine’s older sister, Elizabeth, was the star attraction for young naval officers—but Catherine was intrigued by “the handsomest person I had ever seen in my life.” She described the young submarine captain as having “curly, blond hair, which definitely was a little bit too long because he had just come in from weeks at sea and had not had a chance to have it cut.” She “kept thinking what a really lovely person this was,”4 and by the time Skipjack was ready for sea the following spring, Chester and Catherine had begun a lifelong ritual of writing each other daily letters whenever they were apart.

On March 20, 1912, Skipjack was conducting normal surface operations in Hampton Roads, when W. J. Walsh, a fireman second class, lost his footing and slipped overboard. It quickly became apparent from Walsh’s thrashing that he was not a swimmer and was in immediate danger. Nimitz saw the situation and without hesitation jumped into the water. He reached the sailor with a few strong strokes, but between Walsh’s panic and the tide, Nimitz could not fight their way back to the Skipjack. Instead, it suddenly looked as if they both might be swept out to sea. With grim determination, Nimitz kept Walsh afloat until a boat from the nearby battleship North Dakota finally picked up both of them.

It was an act of personal courage typical of Nimitz, but it also set the naval base at Hampton Roads buzzing with the story of an officer who had risked his life for an enlisted man. Nimitz, however, was never one to draw such distinctions. The Treasury Department later awarded him its Silver Lifesaving Medal, but with his usual modesty Nimitz simply reported to Catherine the next day, “I had to go swimming yesterday, and it was awfully, awfully cold.”5

That same spring, Nimitz was invited to address the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, on the subject of defensive and offensive tactics of submarines. It was a highly unusual honor for a twenty-seven-year-old lieutenant, but it showed again that his willingness to work hard in whatever assignment he drew had its rewards. The lecture was classified, but Nimitz became a published author when an expanded, nonclassified version appeared in the United States Naval Institute Proceedings the following December.

In keeping with generally accepted naval thinking, Nimitz did not presage any great strategic role for submarines, but he certainly recognized their growing offensive importance. “The steady development of the torpedo,” he wrote, “together with the gradual improvement in the size, motive power, and speed of submarine craft of the near future will result in a most dangerous offensive weapon, and one which will have a large part in deciding fleet actions.”

In addition to those smaller submarines slated for harbor and coastal defenses, Nimitz foresaw the development of what would become the “fleet type” submarine, capable of “the same cruising radius as a modern battleship” and easily able to “accompany a sea-keeping fleet of battleships.” He also showed his tactical creativity by suggesting a “ruse” whereby escorts might “drop numerous poles, properly weighted to float upright in the water, and painted to look like a submarine’s periscope.” Nimitz speculated that these decoys might divert an enemy fleet into other waters where submarines were lurking to make an offensive strike.

Interestingly enough, in this era of early radio communications, Nimitz described an elaborate, thirty-foot-tall radio mast that transmitted and received up to fifty miles and could be “taken down ready for submergence in five (5) minutes,” a far cry from the crash dives of thirty years later.6

Service in the Skipjack and later the Sturgeon also made Nimitz by necessity something of an expert in diesel engines. In fact, when the navy decided to experiment with diesel engines in larger surface ships as the transition from coal-fired steam to oil-fired steam was being completed, he was judged the navy’s leading diesel expert, and the year before the outbreak of war in Europe, he was dispatched to Germany to inspect Rudolf Diesel’s operations.

Upon his return to the United States, Nimitz was assigned to the Brooklyn Navy Yard to supervise the installation of two 2,600-?horsepower diesel engines in the new oil tanker Maumee. He and Catherine were married by then, and their first child, daughter Catherine Vance, was born on his birthday in 1914. A year later, he was still working on the Maumee when his son, Chester Jr., was born.

Like Bill Halsey, Chester Nimitz now flirted with leaving the navy. He had a devoted wife and a wonderful, growing family. What’s more, his diesel expertise made him highly sought after by private industry. His navy pay of $240 per month, plus a $48 quarters allowance, paled alongside the $25,000-a-year, five-year contract he was reportedly offered by the Busch-Sulzer Brothers Diesel Engine Company of St. Louis. In fact, had Nimitz played the negotiation game, he might have commanded much more. Instead, after scarcely thinking it over, the quiet, self-effacing Nimitz merely said, “No, I don’t want to leave the navy.”7

With this diesel work on the Maumee, Nimitz was a hands-on officer just as he always was. It wasn’t unusual to find him in overalls and with dirty hands working next to his men. Once, when a scaffold collapsed, he was knocked unconscious and buried under a pile of lumber. But that wasn’t the most serious injury he sustained.

One day, Lieutenant Nimitz had dressed in his whites to give a tour to a group of visiting engineers from all over the country. To keep his hands clean, he put on a pair of heavy, canvas gloves. When one of the engineers asked a question about the exhaust system, Nimitz pointed to the spot in question, as he had done many times. But on this occasion a fingertip of his thick gloves caught between two gears and pulled his finger in after it. The only thing that saved his hand from being chewed to pieces was his Annapolis class ring, which caught in the gears and gave him an instant to jerk his hand away. As it was, he lost two sections of the ring finger on his left hand and was a bloody mess by the time he arrived at the hospital. Characteristically, he wanted to return to finish his tour after being stitched up, but the doctor convinced him otherwise.8

By the time the Maumee was finally commissioned, the war in Europe had been raging for more than two years. At the outset, submarines seemed to be the least of anyone’s concerns. The world’s navies combined could muster only about four hundred boats, and most of these were aging gasoline-powered relics unsafe for combat or just about anything else. France led the way, but in numbers only. Its 123 boats were hardly fit to operate beyond sight of its coast. Great Britain floated 72 subs, but only 17 were newer diesel boats. Russia ranked third in numbers but could barely match France in effectiveness. The United States stood fourth with 34, one-third of them diesel powered, thanks in part to Nimitz’s influence. Finally, there was Germany. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz had long been skeptical of the Unterseeboot (undersea boat), or U-boat, and half of the Imperial German Navy’s 26 vessels were aging smoke-belchers run on kerosene, while the other half were largely untried diesels, many still undergoing shakedown cruises.

At the outset of the war, as befit its role as mistress of the seas, Great Britain used its naval might to impose a blockade against Germany. It was all quite civilized and chivalrous. Under centuries-old international law, British warships had the right to stop any German merchant ship attempting to run the blockade, conduct its crew and passengers to safety, and then either sink or capture the vessel. Neutral vessels were subject to “stop and search” to ascertain that they were not carrying war materials or were not German ships flying a neutral flag as a disguise.

In response, Germany sortied ten of its older submarines to punch a hole in the British blockade. On this first concerted submarine attack in naval history, two U-boats were lost to the elements, and the remainder limped home without recording any damage. Von Tirpitz may well have sniffed and said, “I told you so.”

But a month later, U-9, another older boat, happened upon three aging British cruisers steaming on a straight course at 10 knots. The U-boat fired two torpedoes at the lead cruiser and scored two hits. The cruiser rolled over and sank in less than thirty minutes. But then the U-9’s captain watched in amazement as the other two cruisers, supposing their companion had hit a mine, stopped dead in the water to lower boats and rescue survivors. U-9 fired two more torpedoes into each of the remaining cruisers, and they quickly settled under the waves. In less than an hour, the British navy had lost three cruisers and fourteen hundred men. Now the fledgling U-boat flotilla had von Tirpitz’s attention.

U-boat proponents on the German Imperial Admiralty Staff proposed that Germany ring the British blockade with a wider U-boat blockade of its own. But there were problems with that approach. For starters, Germany’s twenty-four remaining U-boats were hardly enough, and stopping suspected neutrals might well expose the U-boats to aggressive countermeasures, not to mention the issue of how to dispose of the numerous passengers. But such chivalry was about to go out the window. It was about to become a different kind of war.

On February 4, 1915, Germany announced a “war zone” around the British Isles and warned that all British ships within it would be sunk. While Germany declared that it would not specifically target neutrals, it also warned that it might be hard to tell the difference from a periscope and that neutrals entering the zone would do so at their own risk. The unlimited scope and concomitant audacity of this new type of warfare was brought home a few months later when the British passenger liner Lusitania was torpedoed off the coast of Ireland. It sank quickly, with a loss of nearly 1,200 men, women, and children, including 126 Americans.

Swayed by international condemnation over the Lusitania, Germany temporarily backed off its U-boat campaign. When it renewed its efforts early in 1916 to try to force a victory in France, another civilian vessel, the French cross-Channel packet Sussex, was hit by a torpedo, with the loss of fifty lives. Once again, the world cried foul and Germany again reduced its U-boat operations, even as newer and faster boats were rolling down the ways of its shipyards.

By early 1917, the European war was well into its third year of stalemate in the trenches of France. Try as it might, and despite the massive Battle of Jutland, the German navy had been unable to defeat the British Grand Fleet decisively in the North Sea. Germany had to do something to break the British blockade, and it chose to unleash an unrestricted campaign of submarine warfare.

On February 1, fifty-seven U-boats put to sea, and for the remainder of the war, an average of thirty-five to forty boats were on station at all times. The initial result was a shock to Allied morale, as well as to shipping tonnage. One thousand Allied merchant ships totaling almost two million tons were sunk during the next three months. U.S. ambassador to Great Britain Walter H. Page intoned the obvious: “The submarine is the most formidable thing the war has produced—by far.” It threatened an “absolute and irremediable disaster.”

But this unrestricted submarine warfare by the Germans against all shipping also brought the United States into the war and united all but America’s most extreme isolationists in a way that the attack on Pearl Harbor would do a generation later. On April 6, 1917, at the peak of the U-boat offensive, President Woodrow Wilson tossed aside his slogan of “He kept us out of war” and asked Congress to declare war on Germany in response to numerous attacks on American ships.

Congress readily obliged, and the U.S. Navy dusted off its contingency plan for war with Germany, code-named Plan Black. Plan Black called for assembling American battleship might in the Atlantic and destroying the advancing German fleet in one grand battle à la Togo at Tsushima. But Germany was not Russia, and the bulk of its battleship fleet, far from crossing the Atlantic, was cautiously hidden away in German harbors. After the Battle of Jutland, Kaiser Wilhelm was willing to challenge the Royal Navy only sparingly in the North Sea, let alone sail his fleet across an unruly ocean to fight the United States.

Recognizing that most nations prepare to fight the latest war and are inevitably forced to adapt when the next one comes, Rear Admiral William S. Sims, the U.S. Navy’s highest-ranking officer in the British Isles, put it rather bluntly. Sims urged the rapid deployment of as many destroyers as possible to the seas around Britain for antisubmarine warfare and the institution of a convoy system to better protect merchant ships on the Atlantic crossing.

Ambassador Page told President Wilson much the same thing. “If the present rate of destruction of shipping goes on,” Page wrote, “the war will end before a victory is won…. The place where it will be won is in the waters of the approach to this Kingdom [Great Britain]—not anywhere else.”

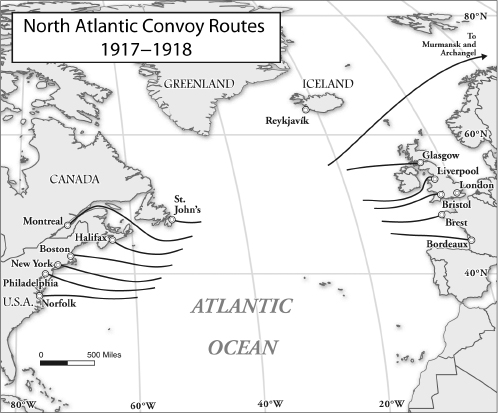

At first, the American naval hierarchy was incredulous, certain that Sims was way off base and had duped Page in the process. Thinking this was the Spanish-American War all over again, the admirals in Washington clung to the idea of one pitched battleship encounter. But as shipping losses continued at a deadly pace, something had to change. U.S. destroyers were finally rushed across the Atlantic, and the British, who had dragged their feet in implementing the convoy system in part out of fear of massing potential targets for German surface raiders, first instituted the convoy system on a Gibraltar-to-London run on May 20, 1917. By September, convoys were in general use on both sides of the Atlantic.9

By then, Nimitz was deep in the middle of the North Atlantic as executive officer and chief engineer on the Maumee. Diesel engines for surface ships was an idea that never got very far, but under Nimitz’s watch the Maumee performed admirably and led the way with a far more important innovation—refueling at sea.

Heretofore, while on duty in the Gulf of Mexico, the Maumee had simply stayed at anchor while its customers came alongside to refuel. But now, given the vastness of the North Atlantic and thirsty destroyers both shepherding convoys and chasing after real and suspected U-boats, the fueling station had to come to them. As with his push for diesels in submarines, Nimitz was an early proponent of underway refueling and he worked with the crew of the Maumee to craft equipment for a full range of procedures.

Maumee was on station in the North Atlantic to refuel the first six American destroyers dispatched to Great Britain. It was tricky and dangerous work. “Spring and early summer in this area is no time for a vacation,” Nimitz later wrote. “Icebergs are numerous and there is much drifting ice. Strong and bitter-cold winds prevail, and there are few days of smooth seas.”10

But in this storm-tossed environment, Maumee was up to the challenge, and by July had refueled all thirty-four of the American destroyers ordered to Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland, for antisubmarine duty. Such underway replenishing would become indispensable twenty-five years later when the U.S. Navy was flung across the wide Pacific, and Nimitz could say that he had been involved from the very start of such operations.

One destroyer skipper who was not yet in the North Atlantic but who was champing at the bit to sail was Lieutenant Commander William F. Halsey, Jr. After cruising around Campobello Island with Franklin Roosevelt, Halsey had taken command of the destroyer Jarvis and refined his tactics and techniques under William S. Sims, then commander of the Atlantic Fleet Destroyer Flotilla.

When the war started in Europe, Jarvis was assigned patrol duty off New York harbor. During these days, Halsey’s seamanship was never in question. By his own account, he was once running through thick fog when “a hunch too strong to be ignored” caused him suddenly to order, “Full speed astern!” When the Jarvis settled to a stop, Halsey hailed a nearby fisherman and asked his position. “If you keep going for half a mile,” came the reply, “you’ll be right in the middle of the Fire Island Life Saving Station!”

“What caused me to back my engines,” Halsey recalled years later, “was probably a feeling of drag from the shoaling water, or the sudden appearance of large swells off the stern; but something told me I had to act and act fast.” And that innate sense of the sea, as well as his commanding presence, was more than enough to make his crew follow him willingly anywhere his can-do demeanor and confident swagger led.

But before the United States entered the war, Halsey was assigned to shore duty as the disciplinary officer at the Naval Academy. Bill Halsey had not pushed the disciplinary limits during his own academy days as much as Ernie King had, but neither was Halsey one to take any great delight in enforcing what would later be called “Mickey Mouse” regulations. He found the shore duty less than challenging.

The highlight of his tour at Annapolis may have been the birth of his son, William Frederick Halsey III, on September 8, 1915. It was a great family time with Fan, four-year-old Margaret, and young Bill, but by the following year, Halsey was clearly bored “nursing midshipmen” and desperately yearned to get back to sea. By the time the United States officially entered the war in April 1917, Halsey’s yearning had turned to an obsession. For nine months, he sat with his gear laid out and waited for orders. Finally, he learned that Sims, his old commander, was leading the destroyer deployment to Europe and that he had Halsey on a short list of officers he wanted assigned to his command. So, Bill Halsey celebrated Christmas with Fan and their children and then shipped off to Queenstown, Ireland, arriving there on January 18, 1918.

Halsey spent what was called a “makee-learn” month as an executive officer on a destroyer pulling convoy duty. There was the occasional rescue or submarine hunt, but mostly the destroyer sailed west with an outbound convoy to the usual limit of U-boat activity—about five hundred miles west of Ireland—and then picked up an inbound convoy to escort back east. The normal routine was five days at sea and then three days in Queenstown to enjoy the liquid hospitality of the Royal Cork Yacht Club.

After this quick apprenticeship, Halsey was given command of the destroyer Benham and then the Shaw. Convoy duty continued, along with chases of suspected U-boats. Although Halsey later admitted that he never actually saw a U-boat, his ships dropped their share of depth charges. “First egg I have laid,” he recorded in his diary. Later, when his seniority put him in command of two U.S. destroyers and two British sloops, he confessed that he “had the time of my life bossing them around.” It was Halsey’s first experience in multiple command in a war zone, and he was “proud as a dog with two tails.”11

The member of the foursome who would sit atop the American naval hierarchy twenty-five years later, and who gained the most insight into fleet operations during World War I, was Ernest J. King. After his baptism piloting the Terry back from the Gulf of Mexico, King considered himself a destroyer man and got command of the new one-thousand-ton Cassin, which was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet Destroyer Flotilla. In short order, he became the commander of a four-ship division. The war had begun in Europe, but the United States was still a declared neutral.

In 1915, King got a summons, much as William D. Leahy had earlier received, from Henry T. Mayo, who by now was a vice admiral and commander, Battleship Force, Atlantic Fleet. Once again, King mulled over the politics: Should he stay with destroyers and hope to get into the fight, or accept a staff appointment with Mayo? This decision was easy, however, as Mayo was definitely considered an up-and-comer and the probable commander in chief, Atlantic Fleet, by the following summer.

King reported to Mayo’s staff in December 1915 as staff engineer, but he was by then far more interested in operational planning than mechanics. When the admiral’s staff produced a fleet plan dictating each destroyer’s course and speed, King boldly challenged it as unnecessary supervision. Surely, King argued, destroyer captains were capable of devising their individual operations within the broader fleet directives. The next morning, King was hauled before a peeved Admiral Mayo, who might well have told him to mind his own duties or pack his seabag. Instead, the admiral heard King out and agreed to test his captains with more discretion as to their own ships.

In King’s mind, he was taking a page from his hero, Napoleon, who instructed his marshals in the grand strategy but permitted them certain discretion in its implementation on their particular piece of the battlefield. To King’s credit—and perhaps relief—the destroyer captains performed admirably on their own initiative, and King’s standing with Admiral Mayo increased as a result.

Thus, when the United States finally entered the war and Mayo had indeed become commander in chief, Atlantic Fleet, King was right at his side, supervising the required buildup of men and ships and completing the transition from coal- to oil-fired propulsion plants. But King’s most valuable experience may have come when he and Mayo sailed for Europe in August 1917 and confronted the issue of how the Americans might best work together with their new British allies.

Admiral Sims was already in Great Britain rushing destroyers into service and implementing the convoy system. For a time, Sims feared that Mayo might assume direct tactical command in Europe and push him aside. But instead Mayo, with King in tow, embarked on a round of diplomatic visits both in Great Britain and on the continent. During these visits, King formed his first impressions of the British general staff and its rather ponderous, ritualistic way of doing business over elaborate lunches and dinners—both floated with ample spirits. The no-nonsense King was not particularly impressed, and this early exposure would color his later reactions when he was a key participant at Allied planning conferences during World War II.

Mayo and King, who by now was a commander and serving as Mayo’s deputy chief of staff, also spent their share of time as guests of the Royal Navy. Its battleships and cruisers were still impressive, but they hadn’t seen action against the German navy since the Battle of Jutland in 1916, when neither side had been willing to risk the all-out, Nelson-like tactics that may have been the price of complete victory. Despite some 250 ships on both sides, the direct dreadnought-to-dreadnought clash to the death never occurred. The survivors in the German fleet were quickly spirited away to safe ports for the duration, and Great Britain, while it lost more ships and sailors, retained control of the North Sea and the integrity of its German blockade. But there were many critics on the British side who were certain that the Admiralty had parried here and there during the action and lost the chance to annihilate the Germans in another Tsushima.12

So the Royal Navy now paraded its battle fleet in routine North Sea maneuvers while Mayo and King had plenty of time to ponder the lost opportunity of Jutland and the future of such fleet-to-fleet encounters. With submarines a threat, and on one occasion King came under enemy fire from aircraft, it was clear that naval warfare was changing. King was a willing pupil under Mayo’s tutelage, and he continued to advocate the ongoing study of strategy and evolving tactics for all naval officers so that they would be prepared for these changes.

As always, King could be brash, arrogant, argumentative, and even hostile to juniors and superiors who failed to measure up to his way of thinking. His volcanic temper with his own subordinates became legendary, and King also bristled and frequently argued with any criticisms that came his way from senior officers.

Admiral Mayo seems to have been one of the few officers in the entire navy whom King truly respected and admired. By King’s own admission, Mayo’s influence on his career “was more decisive than that of any other officer that he had encountered.” This may well have been because Mayo came to refine and espouse the management principles that King himself had proposed some years before in his prizewinning essay on shipboard management.

According to King, the lesson he learned from Mayo that most influenced his later career was “a proper realization of ‘decentralization of authority’ and the ‘initiative of the subordinate.’ ” To Mayo, this meant “passing down the chain of command the handling of all details to the lowest link in the chain which could properly handle them,” while keeping in hand matters of policy and strategic importance.

Reminiscing about Mayo on the admiral’s eightieth birthday some twenty years later, King, by then himself an admiral, recalled that Mayo “had an exceptionally open mind, he was always willing to hear all sides of a situation and to discuss any matter of moment.” But while Mayo trusted his subordinates, he also required of them “due performance of their proper responsibilities.”

There was never any doubt, King continued, that Mayo was always the commander in chief. He alone was in charge. King may well have been describing the goals to which he aspired in his own commands, but only time would tell whether he was truly able to emulate his mentor or simply pick and choose from among his attributes.13

By and large, World War I for the U.S. Navy proved a very focused and linear affair. The line ran across the North Atlantic between the East Coast and Great Britain and became a conduit of men, materiel, and provisions to both Britain and France, as well as to Russia. Thus, the navy’s role became primarily one of convoy duty and antisubmarine warfare, just as Admiral Sims had urged. The proud U.S. battleships steamed about and one division was temporarily assigned to assist the British fleet, but there was no great clash for the American fleet reminiscent of Dewey at Manila Bay or Togo at Tsushima.

The Americans, however, also decided to dispatch a submarine flotilla to Great Britain. Consequently, the order went out in August 1917 to Chester Nimitz, now a lieutenant commander, to report as engineering aide to Captain Samuel S. Robison, the commander of Submarine Force, Atlantic Fleet. Robison appreciated Nimitz’s mechanical abilities, but this staff assignment also exposed Nimitz to a wider view of the navy’s command structure. It got him out of the engineering room and started up the ladder of command.

The deployment of U.S. submarines to Europe during World War I was of little military importance, but it gave Robison and Nimitz a close-up opportunity to study the tactics and engineering of both British and German boats. Interestingly enough, in this early period of submarine warfare, the countermeasure that had the highest percentage of effective kills against enemy submarines was opposing submarines. Three hundred Allied destroyers and sub chasers deployed exclusively to hunt U-boats sank forty-one, but an average force at sea of thirty-five Allied subs accounted for eighteen German sinkings.

There is no question that both sides in World War I learned the growing importance of the submarine. Certainly, the Germans saw how close they had come to choking off Great Britain. The Allies belatedly embraced countermeasures and convoy tactics that would be ready at the outbreak of the next conflict. In the final analysis, of course, the greatest naval lesson of the war may have been to prove once again Alfred Thayer Mahan’s thesis of the importance of sea power—however evolving—on history. It would be even more essential to the defense or conquest of nations in future struggles.14

Some would call the recent conflict “the war to end all wars,” but for the American navy, World War I was only a dress rehearsal for a much deadlier and far-reaching conflict two decades later. When that conflict came, the submarines and aircraft that had come of age during World War I would become strategic weapons far outclassing the heftiest of battleships. And the four sailors who traced their bonds to their years at the U.S. Naval Academy would be catapulted into positions of leadership and responsibility the likes of which they could not have imagined during their days at Annapolis.