If countries reflexively prepare to fight the last war, can commanders help but be influenced by the latest battle? Bill Halsey’s buddy Raymond Spruance had done his strategic duty in defending the amphibious landings on Saipan and in the process had still put his planes in a position to render the bulk of Japanese naval aviation—save for those who would turn to kamikaze attacks—largely impotent. But according to some critics, Spruance had missed a chance to destroy the main Japanese fleet.

The next opportunity for destroying the Japanese fleet—even carriers whose decimated air wings rendered them largely decoys—had proved irresistible to Halsey, a dogged fighter who had missed the earlier clashes at Coral Sea and Midway. Even Halsey’s most vehement critics can understand his rationale for his actions at Leyte. Far less understandable are Halsey’s actions in not one but two crippling typhoons in the weeks and months that followed.

After the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Halsey’s Third Fleet was called upon to provide continuing air support for MacArthur, as his “I have returned” pronouncement for a time appeared a little premature. Leyte land operations bogged down in a sea of mud and miserable monsoon-weather flying conditions. Japanese land-based aircraft on Luzon, lying to the west in a protected rain shadow, took advantage of this and repeatedly challenged American control of the air above the eastern Philippines. A major part of this effort was led by the first concerted kamikaze attacks, which momentarily upset the fighting punch of Halsey’s carriers, as well as those transports and supply ships that the Japanese targeted off the beachhead.

Just as the Japanese navy had determined the defense of the Philippines to be a do-or-die effort, the Japanese army made a similar effort. In fact, it had managed to land two thousand reinforcements on Leyte even as the sea battles raged around it. Because many of Kinkaid’s CVEs were exhausted and short of aircraft after the Leyte Gulf fight, MacArthur requested Halsey to stay on station around the Philippines with the big carriers of the Third Fleet for another month instead of raiding Tokyo. Nimitz concurred and directed Halsey to do so. Meanwhile, Nimitz’s old shipmate from the gunboat Panay, “Slew” McCain, replaced Marc Mitscher as the commander of Task Force 38 under Halsey.

Operating in concert around the Philippine archipelago, McCain’s carrier planes and submarines took a toll on Japanese transports and shipping to the islands, and by early December a quarter of a million American troops on Leyte had succeeded in getting the upper hand. But kamikaze raids continued to batter Halsey’s fleet. One carrier after another sustained heavy battle damage.

McCain had enough aircraft to initiate what came to be called the big blue blanket. It gave air cover to the big blue fleet by monitoring every Japanese airfield within range and attacking the enemy’s aircraft as they took off. There were also innovations in recognition signals. Returning American aircraft did a slow flyby of picket destroyers to keep kamikazes from slipping into the landing pattern and then plunging onto a flight deck. Finally, the Third Fleet retired eastward to the anchorage at Ulithi for a well-deserved two-week rest and resupply.

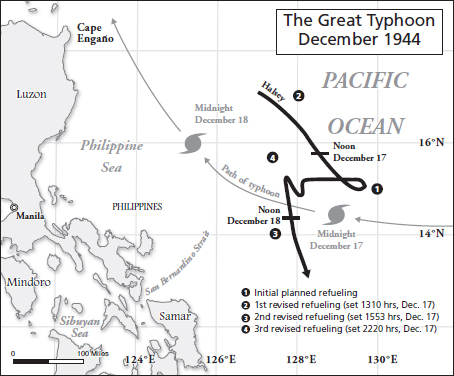

Halsey and his staff used the interval to plan their next set of operations. Their first priority was to return to the Philippines and support MacArthur’s planned invasion of Mindoro on December 15. Even as they did so, Halsey was anxious to strike westward and take operations into the South China Sea. On December 17, with commitments to MacArthur to strike Luzon on December 19, 20, and 21, Task Force 38 steamed for a refueling rendezvous some three hundred miles east of the Philippines.

As the refueling of destroyers from the larger ships started while en route, Commander George F. Kosco, Halsey’s chief aerologist, fretted over a series of weather warnings that were both vague and at least twelve hours old. Somewhere in their part of the wide Pacific, a tropical storm was gathering strength. That noon, as Halsey joined his staff for lunch aboard the New Jersey, he got a close-up glimpse of what lay ahead.

The destroyer Spence came alongside the big battleship’s starboard side to take on fuel. This was in the lee of the battleship and should have made for easy maneuvering. But a fluky 20- to 30-knot wind was blowing across the running sea, and it proved difficult to hold the destroyer in position. Halsey watched from his flag mess as the Spence first dropped astern and then raced ahead, only to drop astern again, all the while pitching and rolling heavily. Suddenly, the Spence yawed sharply to starboard and then twisted back to port on a collision course with the New Jersey. Halsey reflexively ducked as the destroyer’s superstructure came within feet of slamming into his flagship.1

Kosco quickly excused himself from lunch and went to the navigation bridge to analyze the latest weather information, while Halsey himself was soon swamped with numerous reports of similar fueling difficulties throughout the fleet. Well versed in at-sea refueling though they were—a far cry from Nimitz’s early experiments during World War I aboard the Maumee—Halsey’s sailors reported hoses snapping like bullwhips and the lighter destroyers bouncing wildly with all the control of fishing bobbers.

Finally, Halsey ordered refueling attempts to cease and set a new rendezvous location with the services group for 6:00 a.m. the next day, one hundred and fifty miles to the northwest. These decisions were made in large part on Kosco’s best guess that the storm was 450 miles to the southeast and would track north to northeast and clear the fleet to the east. Actually, it was only about 120 miles from Halsey’s position, and far from veering northward, it was doggedly following the fleet northwest on this new course.

Halsey’s commanders followed his orders, but not all did so without questioning his sense of the weather. Captain Jasper T. Acuff, commanding the services group of oilers and support ships, conferred with the captains of two escort carriers in his group, and all three concluded that the 6:00 a.m. rendezvous would be smack in the path of what increasingly appeared to be a building typhoon. On board the new Essex-class carrier Lexington, Rear Admiral Gerald Bogan, commander of Task Group 38.2, was certain, based on his own aerologist’s report, that a typhoon was forming and moving in a northwesterly direction with the fleet.2

For some reason—probably because these subordinates assumed that Halsey had both sea sense and weather information superior to theirs—these analyses were not passed on to Kosco or the admiral himself. Instead, Halsey conferred with Kosco and, as winds continued to build, picked a second revised refueling location directly to the west. But instead of diverging at a wider angle from a storm track running north or northeast, this course took the fleet on a course generally parallel to the oncoming storm. Bogan finally radioed his frustration to McCain, the task force commander, and urged that the best chance of escape lay to the south.

As it turned out, this second revised rendezvous location would have been better than the third location that Halsey picked late on the evening of December 17. Evidently concerned about his commitments to MacArthur to launch air raids on December 19, Halsey set course for another revised rendezvous at 7:00 a.m. on the 18th back to the north. He apparently ignored Kosco’s advice that doing so might bring the fleet right into the path of what Kosco was convinced was becoming a powerful typhoon.3

Halsey asked McCain’s advice as to the storm’s location, but McCain merely replied that he thought the fleet should not attempt to refuel under the current conditions. Aboard the key command ships, everyone seemed to have a different opinion as to where the center of the storm was located. By 5:00 a.m. on December 18, it was in fact about ninety miles east-southeast of the New Jersey.

Halsey finally ordered a course change to 180 degrees due south, but the delay running north had kept the fleet in the crosshairs of the advancing storm. By 8:00 a.m., McCain, with Halsey’s concurrence, ordered a momentary jog back to the northeast in yet another attempt to refuel the destroyers before turning south again, but this lapse only had the effect of holding the fleet in the storm’s path.4

By the time McCain changed course to 220 degrees and then finally ordered the ships to steam at will, the battleships and large carriers had been battered, but the smaller destroyers and services ships had suffered a frightful toll. “No one who has not been through a typhoon can conceive its fury,” Halsey later recalled. “The 70-foot seas smash you from all sides. At broad noon I couldn’t see the bow of my ship, 350 feet from the bridge. What it was like on a destroyer one-twentieth the New Jersey’s size, I can only imagine.”5

But Halsey certainly had a very good idea. He was first and foremost a destroyer man. If he was being tossed about on the mass of the New Jersey, he had to know what hellish conditions his destroyers and destroyer escorts were facing, not to mention the pitching decks of his smaller escort carriers. Where was the innate seamanship that Halsey had exhibited so often throughout his career? Where was that intuitiveness that had caused him to bring the destroyer Jarvis to a halt in a dense fog off the coast of Long Island in 1914?

If other experienced commanders in his fleet had qualms about the weather, why did Halsey vacillate on a course to clear the storm? Even if he was getting conflicting estimates of its track, the general consensus was that a decided run south on the afternoon of December 17, rather than repeatedly trying to turn back north, would have avoided much of the catastrophe.

The answer seems to be Halsey’s determination to keep his commitment to support MacArthur—a commitment he may have been feeling particularly sharply in light of criticism that he had forsaken the Leyte beachhead just six weeks before. “Have been unable to dodge storm which so far has prevented refueling,” Halsey signaled MacArthur, as he was unable to strike the intended targets. A few minutes later, Halsey reported to Nimitz, “Baffling storm pursues us.”6 But no matter the reason, there seems in hindsight little rationale to subject a fleet to such a pounding.

Three destroyers, including the Spence, capsized, with the loss of most of their crews. The Independence-class light carriers Cowpens and San Jacinto suffered minor damage, but their sister, Monterey, was almost lost when loose aircraft on the hangar deck ignited a horrible inferno. A thirty-one-year-old lieutenant from Grand Rapids, Michigan, named Gerald R. Ford was among those who led the charge to save the ship. The total toll for the Third Fleet was 790 officers and men dead and 156 aircraft destroyed.

By midafternoon on the 18th, the typhoon’s fury had passed, and a massive search-and-rescue operation was launched. From the Spence’s complement of 336 men, only 24 were pulled from the water. Meanwhile, Halsey stubbornly tried to keep his commitment to MacArthur, and on the 20th he steamed westward toward Luzon. Heavy seas on the 21st and a large measure of damage and confusion prompted a cancellation. The fleet came about and headed back to Ulithi to regroup and repair.

Early on the morning of December 24, Halsey’s battered fleet moved into the protected anchorage at Ulithi, and within a few hours a plane carrying Chester Nimitz touched down in the broad lagoon. Nimitz brought along a Christmas tree and holiday greetings to Halsey and his staff, but once the public pleasantries were over, he sat down with Halsey on Christmas Day and ordered a court of inquiry into the loss of the three destroyers and general damage to the fleet. Save for a few encounters such as at Savo Island, it was a far greater calamity than anything that had befallen the American navy since Pearl Harbor. If this court of inquiry so determined, full-blown courts-martial might later be convened against those found wanting in the discharge of their duties—including, quite possibly, Halsey himself.

The court of inquiry called the principal participants, including Halsey, McCain, Bogan, and Kosco. Halsey wasted no time blaming the weather warning system in the Pacific, at one point calling it “nonexistent.” But when asked just two questions later on what basis he had testified that the storm was curving to the northeast, Halsey gave a long answer clearly indicating that some weather information had been available. Even so, when asked if he had had a “timely warning” of the storm, he maintained that he had had “no warning.” Pacific weather information was indeed somewhat hit-or-miss, but Halsey’s effort to cast blame elsewhere flew in the face of testimony from Bogan and others that local conditions certainly indicated an approaching storm and apparent track.7

It also flew in the face of Halsey’s own testimony. When asked to compare the conditions on December 17, when the Spence encountered its refueling problems alongside New Jersey, with those on the morning of the 18th, Halsey replied, “On the morning of the 17th I was under the impression that we were on the fringes of a disturbance. On that morning of the 18th there was no doubt in my mind that we were approaching a storm of major proportions and that it was almost too late to do anything.”8

And he did nothing. For a period of nineteen hours, Halsey failed to issue a fleet-wide advisory that the storm center was much closer than initially plotted. Focusing on this, the court of inquiry found Halsey “at fault in not broadcasting definite danger warnings to all vessels early morning of December 18 in order that preparations might be made as practicable and that inexperienced commanding officers might have sooner realized the seriousness of their situations.”9

Ultimately, the court held Halsey accountable for “mistakes, errors and faults,” but then backpedaled and classified such as “errors in judgment under stress of war operations and not as offenses.” The court then went on to recommend impressing on all commanders the adverse weather likely to be found in the Western Pacific and urged the navy to upgrade its weather operations with special weather ships and increased reconnaissance planes staffed by qualified weather observers.10

Nimitz approved the court’s opinion, but in his endorsement he got Halsey off the hook a bit further. Noting that the court was of the “firm opinion that no question of negligence is involved,” Nimitz affirmed that not only were Halsey’s errors in judgment “committed under stress of war operations,” but also that they stemmed “from a commendable desire to meet military commitments”—supporting MacArthur.11

When Nimitz allowed himself some measure of criticism, it was limited to a general indictment of the reliance on new technologies over raw seamanship in a memo titled “Damage of Typhoon, Lessons of,” which he sent to the entire Pacific Fleet. Perhaps remembering his own experience with a typhoon aboard the Decatur in his early years, Nimitz found general fault with captains and aerologists alike who placed too much reliance on radio reports and other outside sources for warnings of dangerous weather. It might well be necessary, Nimitz lectured the fleet, “for a revival of the age-old habits of self-reliance and caution in regard to the hazard from storms, and for officers in all echelons of command to take their personal responsibilities in this respect more seriously.”12 No one, of course, should have been more aware of that level of innate seamanship than Bill Halsey.

King concurred in Nimitz’s opinion but softened its indictment of Halsey even more by adding “resulting from insufficient information” after “errors of judgment” and changing Nimitz’s “commendable desire” to “firm determination.”13 It was too late in the war to jettison one of the navy’s biggest heroes. Nimitz knew it, King knew it, and doubtless Leahy and FDR knew it. But on a gut level, perhaps Halsey, too, knew that he had been saved. In the end, Halsey, who was so loquacious about so many things, never mentioned the court of inquiry in his memoirs.

While Bill Halsey was battling Pacific typhoons, a whirlwind of a different sort was coming to a climax in Washington. For several years, there had been discussions about creating a five-star rank above that of the four stars of a full general in the army and a full admiral in the navy. King, in particular, was in the vanguard of those urging the new rank, while George Marshall, typically, was far more reticent about the matter.

Some of the reasons for the higher rank were indeed related to ego, but there were also practical issues. In dealing with the British chiefs of staff, the Americans always came up one star short against the five stars of a field marshal, air marshal, or admiral of the fleet. Aside from such tradition-bound circumstances as whose plane should land first or whose flag should be flown during joint exercises, there was the general perception that somehow members of the American military were not quite equal to their British counterparts, a perception that became even more important when a bevy of Russian field marshals was added to the mix.

But it is also true that on the American side, the ranks of general officers were swelling, and four stars was not the apex it had once been. In the navy, for example, there had been only four prewar slots authorized for four-star rank. At the time of Pearl Harbor, the CNO and the commanders in chief of the Pacific, Atlantic, and Asiatic Fleets wore these stars. (The four-star rank of the Asiatic Fleet commander was more a matter of parity with the other fleet commanders—American and otherwise—than a reflection of the size of the fleet.)

When the Asiatic Fleet was disbanded early in 1942, the four slots were filled by King as COMINCH, Nimitz as CINCPAC, Royal Ingersoll as commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet, and Harold Stark, who managed to keep his rank when sent to London despite no longer being CNO. By that July, Roosevelt had accorded four stars to Leahy upon his return to active duty, and largely through the good graces of Congressman Carl Vinson, Halsey received four stars after his successful efforts in the Solomons. At the same time, Eisenhower was promoted to four-star rank in the army behind only Marshall and MacArthur.

King wasn’t opposed to these promotions, but he wanted a formal policy of advancement and a clear path above four-star rank. King’s own suggestions of the higher ranks of “Arch-Admiral” and “Arch-General” fell on deaf ears. Secretary of the Navy Knox, usually King’s champion, agreed with King on “the idea of an increase of rank for you and Marshall” but thought “Arch-Admiral” sounded “too much like a church designation.”14

Leahy claimed that Roosevelt first mentioned his promotion to five-star rank early in January 1944 by saying, “Bill, I’m going to promote you to a higher rank.” Gracious Leahy expressed surprise and told FDR that “the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who were working for him exactly as I was were entitled to the same reward as he proposed to give me.”15

Considerable debate in Congress followed over nomenclature and the number of authorized slots. In the end, the British equivalents of “admiral of the fleet” and “field marshal” were also discarded for the more uniquely American “fleet admiral” and “general of the army.” When Congress finally passed the legislation on December 14, 1944, it authorized four officers of five-star grade in the active rolls of each service at any one time. And, significantly, the legislation provided that the president’s authority to make such appointments and the grades themselves would terminate six months after the cessation of the current hostilities.16

When these sets of five stars began to fall, it was no surprise that the first to receive them was Bill Leahy. In a military establishment where date of rank determines seniority within grades, there could be no question that Leahy was both FDR’s and the country’s ranking officer. His appointment was dated December 15, 1944, and the other recipients followed, one day after another.

With Leahy and the navy taking top billing, there was also no question—in Roosevelt’s mind, at least—that George Marshall would become the first five-star general of the army. Whatever glories others had found on far-flung battlefields or nurtured in the public’s perception of them, they all owed the organization and the resources that made their efforts possible to Marshall’s leadership.

King’s promotion to fleet admiral was dated December 17, 1944, making him third on the five-star list. For someone who had once worried about approaching retirement age before achieving his goal of CNO, it was the epitome of his expectations.

The fourth slot belonged to the army. Even though Dwight Eisenhower had skillfully led supreme Allied commands from Torch to Overlord and was arguably the principal implementer of Germany’s defeat, there was another that Roosevelt felt compelled to put ahead of him. Douglas MacArthur could hardly argue with the choice of Marshall, but politics and public image dictated that he receive five-star rank ahead of his one-time “clerk.” And whatever the realities of MacArthur’s role in the Pacific, in the minds of a great many Americans, he personified the Pacific war effort. Chester Nimitz held much the same position on the navy’s side and became the third fleet admiral on December 19. Eisenhower got his five stars the next day.

Roosevelt might well have stopped there with six—three fleet admirals and three generals of the army. But parity on the American Joint Chiefs, as well as with the British air marshal on the Combined Chiefs of Staff, encouraged the appointment of Army Air Forces Chief of Staff Henry H. “Hap” Arnold to the seventh set of five stars on December 21. (In 1949, with the department of the Air Force now separate from the army, Arnold would be honored as the only “general of the air force” and the only American to hold five-star rank in two military branches.)

Then FDR did pause. No one on the navy side had to be promoted to the fourth fleet admiral slot, but with four five-star generals of the army, the navy was not about to be left out. But who would be accorded the fourth set of five stars as a fleet admiral?

King, who rarely allowed himself to be put in an awkward position, seems to have been forced into just such an uncomfortable spot on this issue. James Forrestal, who had become secretary of the navy following Frank Knox’s death, told King to make a recommendation. King was inclined to pick Raymond Spruance, the only officer in the navy who King felt was his intellectual superior and who had been steadfastly reliable from Midway to the Marianas.

But Congressman Carl Vinson, who as chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee in the House of Representatives since 1931 was the veritable godfather of the navy, remained Bill Halsey’s champion. To slight Vinson in this regard might spell trouble for King, since he had lost his own protector in Frank Knox and would have a rocky relationship with Forrestal. Then there was Halsey’s public persona. He had become “Bull” Halsey, the hard-hitting darling of the press who was seemingly immune from mistakes or too much scrutiny of his military decisions. His reputation had been built on the Marshalls and Wake Island raids of early 1942, when the country desperately needed a hero, and solidified by his gritty talks with war correspondents in the Solomons. Few ever mentioned that when Halsey assumed command of the Third Fleet from Spruance in August 1944, he had not had a sea command in two and a half years—since before Midway—and that the logistics of commanding the Third Fleet could not begin to compare to those of commanding the smaller task forces he had overseen in the earlier hit-and-run raids.

Bill Halsey’s most vehement defense of his actions throughout—whether at Leyte Gulf or in the typhoon—was always that only the man on the spot could truly understand what led him to the decisions he made. Seventy years later, that remains a valid point, and the very fact that those seventy years have done little or nothing to dim Halsey’s reputation in the popular press or among the general public shows how extraordinarily revered he was. Everyone needs heroes, and for the American people and the United States Navy in World War II, Bill Halsey was the hero who personified the effort and the ultimate victory.17

This says something about men making their reputations on the battle line, even if the contributions of those in staff assignments frequently provide the battlers their opportunities—as Spruance readily acknowledged of Nimitz at Midway. Leahy, and to a lesser extent Nimitz, both eschewed the spotlight. Nimitz got more of it because he was more readily accessible to the press and his subordinates. Leahy is usually present in the photos of the major strategic conferences of World War II, but his role—which fit him perfectly—was to give advice and support to only one man, FDR.

King was never shy about promoting his talents, but despite his role as COMINCH, it was Nimitz and his principal deputies who got more press attention. And while King usually held the respect of even his critics, he was simply too aloof and lacked the likability and follow-you-anywhere personality that radiated from both Nimitz and Halsey. From Nimitz, it came from studied calm; Halsey’s resulted more from his volcanic “hit ’em again harder” football mentality.

If Marshall and King had agreed on only one thing, it would have been that each of them had their public heroes to nurture and attempt to control: MacArthur for Marshall and Halsey for King. And in the end, it was this recognition of Halsey’s place in the public consciousness that seems to have tipped King from Spruance to Halsey in recommending that fourth set of five stars. Halsey was too much of an institution in the American press to be denied.

Had Spruance been of a similar ilk as Halsey and sought the spotlight rather than shunned it, the result might have been different. As it was, Spruance passed off attempts to be called the hero of Midway by recognizing the staff he had inherited from Halsey and Frank Jack Fletcher’s commanding role.

“It was a tough thing to decide who should be the fourth five-star admiral,” King wrote to Spruance after the war. He had “hoped that the Congress would make a fifth five-star admiral.”18

“The fourth five-star promotion went where it belonged when Bill Halsey got it,” Spruance replied, “and I never had any illusions about Congress ever creating a fifth vacancy.” Then, in a show of the genuine humility and decency that made Raymond Spruance the man he was, he told King, “I have always felt that I was most fortunate in being entrusted with the command of the operations that I had during the war, and their successful outcome was ample reward in itself.”19

Heat-of-battle decisions at Leyte and the typhoon aside, it is difficult to argue that Bill Halsey didn’t deserve the five stars of a fleet admiral, although with King’s procrastination, he didn’t receive them until December 11, 1945. But there is convincing evidence that of the remaining American admirals of World War II, Raymond A. Spruance was no less deserving of five stars than Halsey. Indeed, with the exception of Spruance, it is difficult to imagine another of their contemporaries on the same level as Leahy, King, Nimitz, and Halsey. In 1950, Congress resolved a similar dilemma in the army when it accorded Omar Bradley a fifth set of army five stars, in part for his postwar role. It could have done Spruance similar justice by making a similar provision for the navy.

As it was, Nimitz tried his best throughout the 1950s to get Carl Vinson to revisit the five-star issue for Spruance. “I appreciate more than I can tell you,” Spruance wrote Nimitz in 1957, “what you said to Mr. Vinson about me—not that I have any idea that anything can or will be done in the matter at a time like this, but it is very gratifying to know how you feel. The good opinion of my fellow officers in the Navy means a great deal to me, and you and King are at the top of my list in that respect.”20

And what of Spruance and Halsey, who had been prewar buddies in California? “So far as Bill Halsey and I are concerned,” Spruance wrote Halsey’s biographer nine years after Halsey’s death, “I was always a great admirer of Bill, as we had served together prewar in destroyers; and I was most happy during World War II to go to sea again under his command.”21

Before Bill Halsey received his five stars, however, there was to be one more controversy on his record. King was right. There was not one typhoon, but two.

After the court of inquiry into the December typhoon concluded, the Third Fleet sailed from Ulithi to conduct air raids against Formosa and the Ryukyu Islands in an effort to stifle the flow of reinforcements to the Philippines. A few days later, the fleet struck northern Luzon to pave the way for MacArthur’s landings at Lingayen Gulf north of Manila. Once again, kamikaze attacks were the principal threat to the fleet until McCain was able to spread the big blue blanket even wider.

On the evening of January 6, 1945, Halsey led Task Force 38, the fighting core of the Third Fleet, through the Luzon Strait between the Philippines and Formosa and into the South China Sea—what had once been considered a veritable Japanese lake. Reports that the battleships Ise and Hyuga, which had retreated from the Cape Engaño action off Leyte largely intact, were lurking about again got Halsey’s combative juices flowing. No battleships appeared to oppose him, but Third Fleet aircraft sank forty-four lesser ships and destroyed large numbers of Japanese aircraft that now would not find their way to reinforce the Philippines.

By January 25, Halsey and his ships were back in the safety of Ulithi Lagoon, and it was time for Halsey and McCain to rotate their commands to Spruance and Mitscher. Gruff guy that he could be, Halsey was also a sentimental sort, and he always had kind and affectionate words for his subordinates upon leaving a command. “I am so proud of you that no words can express my feelings,” he told the Third Fleet. “We have driven the enemy off the sea and back to his inner defenses. Superlatively well done!”22

So as Halsey and McCain returned stateside for a little rest and relaxation and to plan future operations, the task of invading Okinawa, in the Ryukyus, fell to Spruance and Mitscher. First, there was the campaign against tiny Iwo Jima, a five-week ordeal to capture eight square miles of rock that cost the lives of almost seven thousand Americans. Once the U.S. flag was raised on Mount Suribachi and the rest of the island secured, Iwo Jima was used as an emergency landing base for B-29s bombing Japan and as a staging area for the next step to Okinawa. Those landings began on April 1.

Nimitz had planned to rotate commanders from Spruance and Mitscher back to Halsey and McCain at the end of the Okinawa campaign, but the island proved tough. The American Tenth Army spent six weeks in the spring of 1945 barely moving against Okinawa’s devilish array of pillboxes and caves, while supporting navy ships offshore endured furious kamikaze attacks. Nimitz decided to rotate command at the end of May whether or not Okinawa was subdued.

This change occurred between Spruance and Halsey on May 27, 1945, and between Mitscher and McCain the following day. Once again designated Task Force 38, McCain’s various task groups continued to pound Okinawa and provide air support over the island.

Then the weather began to sour. Early on the morning of June 4, with McCain aboard the carrier Shangri-La in tactical command of the task force, McCain recommended to Halsey on the battleship Missouri that due to an approaching storm, air operations should be canceled and the task force should momentarily retire eastward from the Okinawa area. Halsey agreed and ordered a course to the east-southeast at 110 degrees, even though McCain had recommended due east. Part of the problem would become that the oncoming storm had split in half, with one portion trailing away to the west but a greater concentration gathering strength to the south.

By 8:00 p.m., Task Force 38 consisted of Task Group 38.1, which had just completed refueling and was under the command of Rear Admiral J. J. “Jocko” Clark; Task Group 38.4, which had been with McCain and Halsey all along; and Services Squadron 6, the oilers, cargo ships, and escort carriers under the command of Rear Admiral Donald B. Beary. McCain, still in overall tactical command, wanted to keep moving east out of the path of the storm. But he consulted with Halsey, who ordered a U-turn to the northwest and settled on a course of 300 degrees—slightly north of due west.

“What the hell is Halsey doing,” McCain asked his staff incredulously, “trying to intercept another typhoon?”23 Later, with Halsey’s concurrence, McCain brought the fleet to due north, but the tightly packed southern half of the storm still had the ships in its sights. Halsey and McCain were in Task Group 38.4 leading the line, with Clark’s Task Group 38.1 in the middle, about sixteen miles to the south, and Beary’s services group following another eighteen miles south of it.

As the task force ran due north, the typhoon struck with a vengeance. Task Group 38.4 was far enough north that it rode out the fury with little damage. Beary made the mistake of signaling his ships to proceed independently to the northwest—right into the storm center. But it was Task Group 38.1, in the center of the fleet, that took the brunt of the storm’s punch.

At 4:00 a.m. on June 5, Clark requested permission to steer clear of the storm center by turning to a course of 120 degrees. Once again, McCain checked with Halsey, who signaled McCain that Clark was to maintain his heading due north. Evidently, both Halsey and McCain felt they were getting into calmer seas at the northern end of the line, and unlike Clark, neither apparently could see the storm center on his radar.

McCain waited to reply to Clark’s request to turn to 120 degrees while he mulled over Halsey’s insistence on continuing due north. Finally, McCain signaled Clark that he could use his own judgment, but by then, when Clark made a series of course changes in search of calmer seas, the moves left his task group near the eye of the storm.

Clark’s group suffered major damage to the fast carriers Hornet and Bennington, two escort carriers, and three cruisers, including the Pittsburgh, which lost its entire bow. Twenty-six other ships reported minor damage, and 146 aircraft aboard the carriers were destroyed or damaged. The only bright spot was that the human toll—six—was much lower than in the December typhoon.

Clark reported aboard the Shangri-La the next day to confer with McCain about the damage. When he told McCain that he could have avoided the brunt of the storm had he been permitted to deviate from the base course earlier, McCain was noncommittal. It seemed clear to Clark that McCain was reluctant to criticize Halsey’s actions. By the time both McCain and Clark reported to Halsey on the Missouri, it seemed equally obvious to Clark that Halsey was fully aware that his own actions were to blame for Clark’s losses.24

Crippled though it was, Task Force 38 soon regrouped and headed westward for more strikes against Okinawa. Tough Jocko Clark, back on board Hornet, ignored its warped flight deck over the bow and steamed full astern at eighteen knots for two days in order to launch and recover planes. By then, the Okinawa campaign was finally showing signs of winding down, and Task Force 38 withdrew to San Pedro harbor in Leyte Gulf, the navy’s most recent advance base. There Halsey, McCain, Clark, and Beary were summoned aboard the New Mexico to appear before a court of inquiry convened to investigate the second thrashing of an American fleet by a typhoon in just six months.

Halsey led off by once again blaming the weather service, but it was hardly that simple. Clark’s counsel presented a chronological record complete with track charts and photographs of the radar images that showed the task force to have been eastward of the storm path when Halsey ordered the course change to 300 degrees. If the fleet had continued eastward, the storm would have passed astern.

In the end, the court of inquiry concluded that Halsey had failed to heed Nimitz’s admonishment after the December typhoon to improve the coordination and timeliness of weather reports and that Halsey was to blame for the “remarkable similarity between the [two] situations, actions and results.” It further concluded that the proximate cause of the damage to the Third Fleet “was the turning of the Fleet to course 300.”25

Secondarily, the court blamed McCain for his twenty-minute delay in granting Clark permission to steer eastward to 120 degrees. It might not seem like much of a delay, but in the face of this concentrated typhoon, minutes made all the difference. Clark and Beary also incurred some blame because they had continued on courses and speeds “although their better judgment dictated a course of action which would have taken them fairly clear of the typhoon path.”26 Actually following their better judgment in the face of Halsey’s orders to stay the course would, of course, have required a good deal of brass.

The court of inquiry recommended that Halsey and McCain be sent letters of reprimand pointing out their errors and “lack of sound judgment displayed”—lessons, it noted, which might have been learned from the December encounter, but which were “either disregarded or not given proper consideration.” The court also recommended that “serious consideration” be given to assigning Halsey and McCain to other duties—that is to say, relieving them of their sea commands.27

Halsey’s shot at the fourth set of five stars might have vanished on that note, but once again Nimitz and King stepped in to save him. According to Jocko Clark, Nimitz was privately furious with Halsey and “minced no words in charging Halsey with gross stupidity in both typhoons, especially the latter, where Halsey had good weather information.”28 But such an outburst, if indeed Nimitz made it, would never be given a public airing.

“CINCPAC has considered,” Nimitz wrote the court in his official response, “not only the events under inquiry, but the outstanding combat records of the officers to whom responsibility has been attached in this case.” Halsey had “rendered invaluable service to his country. His skill and determination have been demonstrated time and again in combat with the enemy.”

King retraced the court’s opinion by noting in his own endorsement, “The gravity of the occurrence is accentuated by the fact that the senior officers concerned were also involved in a similar, and poorly handled situation, during the typhoon of December 1944.” King felt that Halsey and McCain could have avoided the worst of this second storm “had they reacted to the situation as it developed with the weather-wise skill to be expected of professional seamen.” But that was the end of his lecture. “Notwithstanding the above,” King wrote, he recommended “no individual disciplinary measures be taken, for the reason stated by… Fleet Admiral Nimitz.”29

Halsey was untouchable, but Slew McCain was not so lucky. He was expendable, and Nimitz quietly prepared to relieve McCain of his task force command notwithstanding King’s official pronouncement. It does not seem an exaggeration to say that McCain took the fall for Halsey. McCain had always been a loyal “King man,” and this result may have grated on King at least as much as his public posturing in Halsey’s defense. Small wonder, then, that King would be inclined to admit, “I should not say it but it is true. Halsey made two mistakes; not the great battle; what I had against him were the two typhoons.”30