Ingredients: mirin (sweet rice wine), white granulated sugar, sea salt, kuruma ebi (prawn), and shiba ebi (shiba shrimp)

1

2 Remove shiba ebi’s heads, shells, and tails.

NORI MAKI, TAMAGOYAKI

“To tell you the truth, I am the unworthy disciple of a master who invented the hand roll.”

There is a masterpiece called Sushitsu (Sushi Connoisseur) that was published in 1930. Its mysterious author, Ganosuke Nagase, must have been an educated idler who paid out of his own pocket to enjoy Edomae-style nigiri to his heart’s content. He wrote, “When you roast nori well, as you would unagi (eel), with bincho charcoal, it’s wonderful without losing its aroma or flavor, but there is no sushi restaurant nowadays that practices this.”

In the present day in the Heisei period, Jiro Ono practices this.

Nori is such an important ingredient that it can affect the impression of a sushi restaurant itself. Most customers order nori maki (roll wrapped in dried seaweed) after eating nigiri to round out the meal. If, at that point, the nori tastes fishy or can’t be chewed off because it’s stale, then all the guest’s feeling of satisfaction will vanish.

This is why, every morning at our restaurant, we roast the amount we use per day with kishu bincho charcoal (originated by a merchant called Bincho from Kishu).

We use bincho charcoal because, with ordinary charcoal, the flame rises so high that it burns the nori. We can’t use gas because it emits moisture, nor an electric range because it has weak heating power. If we used an electric range to roast our day’s worth of nori, it’d probably take an hour. However, with bincho charcoal, it only takes fifteen minutes. Plus, it remains crispy even in the evening, and as soon as you put it in your mouth, it melts.

As you know, the heating power of bincho charcoal is extremely intense, so even though the flame doesn’t blaze up, if you don’t pay attention the fire spreads right away.

So I often tell my son, who recently started to work on this part of the prep, “Roast it as if you’re slapping it on the gridiron of the cook stove, and don’t sweep the gridiron with it.”

You can’t roast delicious nori unless you put the flame on it instantaneously at an almost perpendicular angle, then quickly flip it front and back with tekaeshi (a technique typically used for turning over nigiri). If you roast it horizontally as if you’re sweeping with a broom, then the heat doesn’t distribute evenly, and there will be a part that’s burnt. However, this tekaeshi is considered difficult for beginners. Me, I’ve roasted nori every morning for over forty years since I became an apprentice at Kyobashi, and it’s just a matter of getting used to it. Once you get used to it, it’s no big deal.

At any rate, the character of nori is determined by how you roast it. You can’t roast it a hundred percent. If you try to roast it one hundred percent, it burns, so be ready to stop roasting at ninety-five, and equally heat all four corners. Then the color turns vivid beyond recognition and an aroma of the ocean beyond description rises in the air.

The season for nori is winter. In Tokyo Bay back in the day, they were able to catch young seaweed in December that looked as if lacquer were poured into the ocean. However, we can’t even wish for nori like that now.

That’s because they grow nori buds differently than in the past. Until the Tokyo Bay fishermen surrendered their fishing rights in 1962, they used to stick bamboo and brushwood to gather laver in the shallow tideland, and they attached buds there. The buds were underwater and grew at high tide, but at low tide they were exposed to the air and dried out. Ebb and flow. And through this repetition, good buds grew.

In the harvesting season, they picked the ones that were ready to eat, and made them into nori and dried them under the sun. This is how they became roasted nori as aromatic and fluffy as a thick Persian rug, and it melted in the mouth.

Lately, however, fishermen float nets with buds deep offshore. This way, the buds soak in seawater all year round, so they grow faster. They reap with a machine that looks like a relative of a vacuum cleaner, and they dry everything electrically, thick and thin all at once, on a belt conveyer. Because they make it this way, the finished product is flat and inconsistently roasted. It doesn’t melt when you put it in your mouth.

But I run a sushi restaurant. I can’t just indulge in nostalgia. As a sushi chef, my obligation is to roast nori as well as I can in the present day. The only way to bring back the aroma, sweetness, and texture from the good old days is to make it crispy by heating it with bincho charcoal.

I trust my nori salesperson, a pro among pros, and it seems that most of ours comes from the Ariake Sea in Saga. In fact, a regular complimented me a couple of days ago, saying, “You use such nice nori at your restaurant.” He is actually the president of a famous nori wholesaler. We received an endorsement from an authority.

![]()

Because demand has increased, fishermen have started to land sake (salmon) with spawn directly at Choshi Harbor. The freshness is exceptional compared to the time they transported it to Tsukiji via Hokkaido.

However, lately, for some reason, akizake (autumn salmon) ascend earlier, and the season for ikura keeps moving up. Up until very recently, we couldn’t eat delicious ikura unless it was November, but in 1996 they started to appear in early September, and by mid-October the roe were already hard.

Until 1995, September spawns were premature.

But in 1997, akizake with scant roe started to appear in August after the obon festival, and by the end of the month the flavor was plenty developed. At this rate, by October all the roe will be too hard.

Ikura’s asset is the grains’ tenderness. Roe that seems to pop in the mouth, the skin melting, comes from salmon caught offshore. They return to the river where they were born and grew up to spawn, but as they get closer to the mouth of the river, the eggs get hard like ping-pong balls. This is why ikura obtained offshore is the only option.

The timing on shore is also crucial. The skin gets hard when it’s exposed to air for too long. I have to head out early so I’m there when the salmon fishmonger slits the fish’s stomach at seven in the morning.

You can tell with your hands whether they’re hard or soft. But when you come across the ones that seem good, then to be extra careful, pluck a grain and test the quality by putting it in your mouth. The roe’s firmness is consistent in each egg sac, so once you taste one or two, you’ll know.

Ikura is our newest neta. We started serving it thanks to the words of a longtime regular whom I can’t hold a candle to.

This was about fifteen to sixteen years ago. He showed up holding tupperware filled with ikura and said, “I just came back from a business trip to Hokkaido and found extraordinarily delicious raw ikura there. Maybe because they marinate it in shoyu (soy sauce) and mirin (sweet rice wine), it doesn’t have the same fishiness as the salted ikura sold in Tokyo. When I put it on warm rice, it stimulates my appetite, and I can keep on filling my bowl. And I ask you this because I know I can count on you: Can you make even more delicious ikura? I want to bring it home and have it as a side for dinner.”

At Nijyo Market in Sapporo, they marinate raw ikura in shoyu (soy sauce) on the spot. I’d heard it was really popular with tourists, but it was my first time seeing it in person. When I tried it, indeed, there was no fishiness to it whatsoever. It made sense that someone like him who appreciated great flavors would fall in love with it.

Unfortunately, he has since passed away, but this guest was a benefactor who treated me kindly every chance he got. I mustn’t turn down someone like him, I thought, and started studying about ikura right away. I couldn’t help but feel inspired.

Soon after, I perfected the flavor to his satisfaction, and he was overjoyed that he could have my ikura at his dinner table.

So the beginning of our shoyu-marinated ikura was for a regular and not as nigiri neta.

One day, however, I thought: If someone who appreciates good flavors as much as he does is happy with it, then other guests will welcome it as well. So I served it in a small bowl as a sake side, and it was received even better than I expected. And I felt so great about it, I started serving gunkan maki (“warship roll”: nigiri wrapped in nori with the neta on top). In Tokyo back then, sushi restaurants that served raw ikura were rare. Perhaps we were the only one.

But raw ikura has a drawback. We can only use it for about two and a half months in autumn. The time we can serve it is too short.

As I thought about it, I had an epiphany. Right, I should just freeze it. Freeze it, and even that regular would be enjoying delicious ikura rice all year round.

So I put a whole skein of raw eggs in what was at the time a state-of-the-art freezer at minus ten degrees (Celsius) but failed miserably. When I defrosted it, the skin ripped and the liquid inside came out, and we couldn’t use it at all. Then I tried freezing it after dismantling it. But it didn’t defrost well that way either.

So I visited a delicacy store in Tsukiji that handled salted dried goods and asked, “I keep failing at freezing it in this and that way, why do you think?”

And the head guy answered, “It’s not only raw ikura that’s challenging to freeze. Even with kazunoko (herring roe), it becomes crumpled, and after some time, it separates. But if you flavor it, it’ll be okay. The salted ikura that’s in our freezer—the quality doesn’t change even after one year.”

The key was the salt content. After I returned to my restaurant and marinated the roe in shoyu, froze it, and defrosted it, both the flavor and the appearance stayed the way it was when it was raw.

But the problem was the minus-ten-degrees freezer. When I defrosted a batch that had been frozen for about a month, the roe just washed away. I had no idea why. I’d heard that frozen maguro (tuna) didn’t change color after being frozen for many years. I wondered how they quality-controlled maguro. So this time I went to ask the maguro fishmongers. They informed me that they froze it with a minus-fifty-degrees deep freezer that was state-of-the-art at the time.

From there, I went straight to buy this state-of-the-art minus-fifty-degrees deep freezer, since I wanted to serve frozen ikura with the exact same taste as raw ikura. And when they’re frozen in a deep freezer, as the maguro fishmongers president said, ikura doesn’t change a thing even after a few months.

A −50° C freezer, originally acquired to serve shoyu-marinated raw ikura all year round. Frozen in small batches.

However, when you defrost it, the ikura goes weird. And the days of trial and error continued, and I finally came up with a rational defrosting method in the following season.

This is how I do it.

When defrosting, first transfer ikura from the minus-fifty-degrees deep freezer to a minus-ten-degrees freezer. Then after a while, put it in a refrigerator until it’s restored completely to a raw state. This is how we can serve delicious ikura all year round.

Of course, some customers who see how ikura is always displayed in our neta box might say, “Authentic sushi restaurants should adhere to what’s in season. It’s not acceptable to use frozen ingredients.”

They’re right for sure, but back then, when I was trying to come up with the successful method for about two years, all I thought about was how to serve ikura all year round, and seasonality was nowhere on my mind. I wonder how much ikura I tasted back then. I put so many ingredients like tako (octopus) and awabi (abalone) in my stomach until I settled on their flavors. I’m sure I had very many skeins of ikura.

Judging from the number of orders we receive, most people must feel, “What tastes good tastes good.” I have my customers’ support, I believe.

By the way, the shoyu-marinated ikura that I made for my regular was for bowls of rice, so I made it strong in flavor, but ever since I started using it for gunkan maki, I cut back on the salt content. The shari (vinegared rice) has saltiness as well. The tongue feels more stimulation from straight salt, even though shoyu contains it, so we tend to flavor our ikura with the shoyu.

![]()

Many say, “The season for uni (sea urchin) is summer,” but in Tokyo, uni tastes better in the colder months.

In Hokkaido, the home of uni, it’s in season in summer on the west side in the Sea of Japan, and in winter, on the east side in the Pacific Ocean. So almost all year round they can catch uni that’s good to eat, but the “white” kind that I use (ezo murasaki uni/purple sea urchin) is vulnerable to heat, so especially in summer it melts fast. Even when it’s flown in by jet, by the evening, the flesh starts to ooze out.

In the summertime, I also make nigiri with “red” (ezo bafun uni/short-spined sea urchin). This uni is a rare and expensive product, but its bits are harder, so it’s not the best suited for our nigiri. I ate and compared them and came to this conclusion, so I try to use the white.

Anyhow, each bit of the white is the size of an adult’s thumb; first-time customers are surprised. More than anything, the sophisticated sweetness, aroma, and coloring match perfectly with our shari (vinegared rice).

All the raw uni in Tsukiji come from the north. The small uni from western Japan never make it there. They don’t taste bad for sure. They deserve to be called “the best uni in Japan,” as people from Yamaguchi Prefecture brag. However, they can’t catch enough to transport to Tokyo, and it also probably doesn’t last long enough. From the west, they send tsubu uni (grainy sea urchin) soaked in alcohol or salt.

By the way, someone who lives in Yamaguchi Prefecture sent me raw uni from Kudamatsu (Seto Inland Sea), but when I tried it, the smell of the cedar from the box had permeated the uni. The odor bothered me, and a hint of bitterness had also rubbed off. It was unfortunate since they’d sent me supreme-quality uni.

In that respect, they are advanced in Hokkaido and use wooden boxes without any aroma. Before that, they put a sheet of deodorizer in the box. They give it such detailed attention.

At any rate, when it comes to uni, Hokkaido and Tsukiji have a long relationship. Now they use jet planes, but in 1969, they used night trains. When I went to the shore in the morning, many men were carrying boxes of uni on their backs.

When I asked “Where are you from,” they answered “Hokkaido.”

All the people who transported uni were former National Railways workers. I don’t know how it is now, but the retirees from National Railways owned a rail pass that they could use to go anywhere for free.

From Hokkaido to Tokyo must have taken all day at the time. They didn’t yet have any coolers made out of styrofoam, so if they slacked off, then the freshness went away. But they worked out a way to supply uni without getting complaints.

The deodorizing sheets and odor-free wooden boxes are the fruit of their efforts.

The uni I use is a brand called Hadate from Hakodate, and because they grow near the four northern islands that aren’t fished excessively, the pieces are surprisingly fat. There are four ranks—gold, green, blue, and navy—according to the colored labels, but they’re all wonderful to the point you can call all of them specialty products.

At Tsukiji, they sell uni including imported ones in dozens of different levels of rankings. By the way, when I researched the wholesale price one day, there was a huge spread, from 300 yen per box to 15,000 yen per box. The quality runs the whole gamut, and, of course, Hadate is there at the top.

What makes it the best is that there are five pieces of uni from one shell. You have to wash the dirt away with salt water and get rid of the shell particles, and then tighten the flesh and then ship, and if an experienced person doesn’t work on this process, more often than not, the edges of the uni pieces crumble.

Excluding the crumbled uni, and strictly selecting by size, form, color, and sheen, they only place pieces that are up to standard in the gold and green boxes.

So the gold is a very rare, valuable product. That’s because they don’t give the gold stamp unless the uni miraculously fulfills and scores perfect points on three criteria: a viscous grain density; plump veins, indicative of freshness; and a spotless, bright yellow color.

Such superb uni is found to complete only one out of five hundred boxes. Even someone like me who buys uni every day only sees it maybe four or five times per season. In 1996 and 1997, I didn’t see it once. Of course if I do, I definitely buy it, but whoever gets to taste it is extremely lucky. Generally speaking, the green that we use all the time is the best-quality product on the market. The difference between the gold and the green is so subtle that I can’t really tell them apart, to be honest.

I roll uni as gunkan maki (“warship roll”: nigiri wrapped in nori with the neta on top). As you can tell from its name, gunkan maki isn’t a recent invention. When I became a sushi craftsman in 1951, they were already serving it at Kyobashi Restaurant. I don’t remember seeing ikura as neta, but they used to make gunkan maki with uni and even kobashira (small scallops). If I think about the transportation capacity, there was no way they could transport it from Hokkaido, so they were probably using local uni. Uni from Hayama (Sagami Bay) was famous. Although we can’t get ahold of enough, they are sometimes caught in Tokyo Bay or Sagami Bay even now.

Some have a harsh opinion: “It’s nigiri because you nigiru (a Japanese verb meaning ‘grip’ or ‘clasp’). Gunkan maki is not nigiri.”

However, I nigiru even the shari (vinegared rice) in gunkan. If I don’t, the shari doesn’t form itself. So it’s beyond me why anyone would say, “Gunkan maki is not nigiri.”

It’s certain that there is an issue. There are customers who don’t have it right away after I roll the uni into gunkan. Since we use body temperature shari, if the customer yaps away as the gunkan sits on the counter, the uni starts to melt. In extreme cases, the shari becomes soggy and the nori hard to chew off because of the humidity.

It’s the same for any nigiri, but especially with gunkan maki and maki (roll) items, I’m in trouble if the customers don’t have them right after I serve them. So I think I understand the feeling of people who say, “I don’t like gunkan.” But those sushi lovers who “have them as I serve them” appreciate it because uni and nori taste good together. With nori that we roast with bincho charcoal every morning, even if we roll it as gunkan, it doesn’t remain in the mouth. However, there is a regular who orders saying, “No, no, you say so, but please make nigiri with it and not roll it as gunkan.” I asked why, to which he answered, “Uni is the softest of nigiri-dane. So when you roll it as gunkan, the harder nori overwhelms the uni. Even if you roast it with bincho charcoal, the fiber of nori remains in the mouth. But if it’s only the tane and shari, then nothing remains in the mouth.”

This is the guest’s conviction, so I shut up and make a nigiri.

Of course, I can make nigiri with uni. Grab shari and adjust the form, and after putting the neta on it, adjust it again. Unless it’s good-quality uni, the pieces collapse, but Hadate is firm enough.

Many regulars have it as a side, I assume because the rich and sensitive flavor and texture of raw uni go well with sake. Raw uni alone doesn’t satisfy them, so there are regulars who place complicated orders. For instance, “Put thinly sliced ika (squid) and uni in a small bowl and drizzle a little bit of wasabi joyu (soy sauce with wasabi).” According to that particular old face, “When the plain ika, the rich uni, and the spicy wasabi meet, the umami triples. It goes well with sake.”

Tai (sea bream) and hirame (flounder) are served at ordinary restaurants, but if you want to eat delicious uni, become a regular at a good sushi place. It’s sushi chefs who buy the market’s highest-quality product of the day.

Even if the price hikes up, we want to serve good uni. As with hon maguro (bluefin tuna), we use uni as a matter of pride as craftsmen.

![]()

Nori maki (kanpyo maki/dried gourd roll) is profound: “mere kanpyo maki, mighty kanpyo maki.” First off, even housewives make it, so kanpyo maki doesn’t become an attraction for a sushi restaurant unless there is a clear difference in flavor between amateurs and professionals. It’s one of the neta that keeps me on my toes.

This is why we put in unrelenting effort even for just boiling it. We divide 2-kg kanpyo in five parts and boil 400 grams per batch. Cut the kanpyo in the length of a whole nori maki and soak it in water for one day. When it gets soft, sprinkle it with salt and massage it thoroughly to remove the harshness. And the next step is scalding. After scalding, you select the pieces. We check carefully and remove the hard part once and for all. If I find a wide part, then I split it into smaller pieces. Lastly, we flavor it by simmering.

After the lunch service, the entire staff gets together for their meal, made from each day’s leftover tane. On this occasion, excess vinegared rice was steamed and topped with lean meat as tekka don, and chutoro that had changed color was stewed with ginger.

So to finish just the kanpyo, it takes two days.

The crucial point in making delicious kanpyo maki is the selection process. It’s a bother to feel any toughness and discomfort when you put it in your mouth. So we make all the pieces the same soft consistency. If we don’t, it doesn’t become the “Yokozuna of Makimono (the sumo champ of rolled items).”

We don’t waste the hard parts that we don’t serve to our customers. We simmer them in a separate batch from the soft ones, dice them small, and use them as one of the toppings for chirashi-zushi (variety of toppings, mainly seafood, on a bed of rice) that we have in our kitchen. It’s really good when we mix in geso (squid tentacles).

Young people nowadays don’t know the true pleasure of kanpyo maki. They seem to prefer negitoro maki (tuna and chives roll), natto maki (fermented soybean roll), and avocado rolls, but I can’t possibly agree that they taste good. When I act as a customer of Sukiyabashi Jiro and have makimono, first I order nori maki (kanpyo maki) or anago maki (conger eel roll). Whether or not I want cucumber in the latter depends on how I’m feeling that day. I ask the chef to brush a little bit of nitsume (reduction sauce) on the surface if it’s anago maki. Sometimes there are orders requesting wasabi, but our anago goes better with nitsume than with wasabi and nikiri shoyu (thin and sweet soy sauce glaze).

However, there aren’t many customers who know that we can also roll anago, and I have no intention of advertising it as being delicious.

If its popularity increases, we won’t have much tekuzu (sliced edges) left. And if that happens, I’ll feel bad for our young guys. After we close, they make rolls and nigiri with leftover anago. I don’t want to take away this feast from them.

There is one more makimono that’s not so well known: oboro maki (ground and cooked fish roll). There are passionate fans of this. Our oboro is made with shiba ebi (shiba shrimp) and kuruma ebi (prawn) that’s been used as a display in the tane box, so there is enough umami in it. There is no coarse texture or discomfort when you put it in your mouth. Even the color is a beautiful natural pink. According to a regular who is a fan, “I don’t like sweet things, but your oboro is an exception. The soft and sophisticated sweetness and smooth texture go perfectly well with the nori’s aroma and the amount of vinegar in the rice.”

So he always orders oboro maki to finish his meal.

Typically, sushi chefs make oboro with white meat. They drain the fat off boiled whitefish by massaging it under running water, and then grind it with a mortar, so only its fiber becomes oboro. Depending on the management policy of the restaurant, this is sufficient. The chefs don’t feel the need to overstretch and use shiba ebi.

So for our young guys who go back to their hometowns, I teach them tricks for making oboro with white meat. If you use whitefish, you naturally end up with nakaochi (leftover flesh on the spine). You store that in the refrigerator, and once there is enough, you can make oboro.

For nori maki, unless the larger hand-rolled variety is requested, we use makisu (a bamboo mat for rolling). Well, it’s not like I have a stubborn belief that “temaki (hand roll) is not nigiri.” I simply roll how sushi chefs traditionally have for a long time: kanpyo maki taste the best cut in four pieces; six for kyuri maki (cucumber roll), oboro maki, and tekka maki (tuna roll). I think so after trying and comparing.

When I make a roll with my hands, the nori remains crispy. And the aroma of the ocean is fragrant. However, it can be too fragrant, overwhelming the flavor of the core ingredient. So I understand the feeling of people who avoid temaki.

There is another issue with temaki. You have to keep holding it with your hands until you’re done, and if you aren’t quick, the nori becomes hard to chew off because it gets soggy. By contrast, with sumaki (roll wrapped with a bamboo mat) the taste doesn’t deteriorate as soon.

But it’s questionable to decide arbitrarily that “temaki is bad no matter what.” There is no need to criticize and attack people who want to enjoy the aroma and crisp texture of nori. I personally don’t feel that it’s wrong and don’t go intoning, “Pardon me, dear guest, but temaki is not nigiri.”

If there is a request, I make a roll with my hands. This is simply a matter of customer preference.

However, I think there are neta that do well or don’t in temaki form. Takuan (pickled radish) doesn’t. Kanpyo is definitely better rolled with a makisu. Anago, too. Anakyu with anago and kyuri (cucumber) also. As for oboro, it tastes good to roll with makisu, hundred percent. If anything, I’d have tekka maki (tuna rolls) as temaki. In particular, very rich otoro (fatty tuna) tastes great as temaki.

Apparently, the person who invented temaki was the sushi master from Kyobashi Restaurant. A regular saw him making temaki for himself—giving it a twirl with his hands and eating it when he was hungry. And the guest said, “Roll one for me, too.” When that was well received, the boss started serving it to the general public. I heard a story like that. To tell you the truth, I am the unworthy disciple of a master who was “the inventor of temaki.”

![]()

I make traditional Tokyo-style tamagoyaki (Japanese omelette) the way I learned during my apprenticeship. But I improved it a little bit, so ours is moister. That’s because I dramatically increased the amount of shiba ebi (shiba shrimp). Years ago Kyobashi Restaurant put 230 grams of shiba per sheet of tamagoyaki, but ours has 400 grams. We use half shiba ebi and half eggs.

They say they mostly used ground whitefish at sushi restaurants back then. But no matter how good the minced flesh is, there is still fishiness to it. However, shiba doesn’t have that odor. And also because the flesh is soft, the tamagoyaki comes out soft and fluffy.

Lately, shiba catches from the seas around Japan have been poor. Sometimes they limit the amount you can buy, and at such times we use komaki (small kuruma ebi/prawn). Then the tamagoyaki comes out with such a beautiful color that the lack of shiba ebi is almost not an issue. However, the thing with komaki is that it stiffens once it’s heated, so the tamagoyaki inevitably gets hard. That’s the drawback.

No, it doesn’t taste bad. Komaki doesn’t. Its aroma is actually better than shiba’s. But the distinct feature of tamagoyaki is its fluffiness, so if possible, I want to continue using shiba that gives a soft finish. That’s my thinking.

It takes an hour to cook one sheet of our tamagoyaki. There is a way to cook it faster. But you’d have to flip it while the inside was still too soft and might ruin it through carelessness. My son whom I have come to trust to cook tamagoyaki seems to spend a lot of time letting the heat reach the core.

Me, I could cook it much faster. But if I did absolutely everything then my work wouldn’t be passed along to the next generation. That’s why I decided to just watch without saying anything.

It’s the same for any neta, but we flavor tamagoyaki to taste good atop shari. But recently, ninety percent of our customers eat it on its own and not as nigiri. In the past, we all made nigiri with it saddled on shari (vinegared rice).

If there isn’t that vinegared aroma from the bottom, then the true flavor of tamagoyaki doesn’t come out. Of course, it also tastes good rolled. When it’s rolled, you can also taste the true flavor. When it’s paired with vinegared rice or nori, the flavor comes out from the synergy.

![]()

Gari (pickled ginger) tastes good in the season of young shoga (ginger), in spring. From April to May, the young oumi shoga (ginger from Oumi) starts to appear first in Kochi and then in Wakayama. Young shoga like this turns pale pink just by going through vinegar, and it’s refreshing: “Ahhh, the height of spring!” Plus, it has a mild spiciness, so the amount that our customers have increases dramatically. In August, the pink color disappears, but our gari is always young shoga; we never use hard and spicy hineshoga (old ginger). That’s because they dig a cave in the hillside and store young ginger that was just harvested, and probably because the temperature is cold and consistent, it doesn’t age. So our gari’s flavor doesn’t change throughout the year. Lately, new potatoes also start to appear in February or March. These were also stored in a cave the previous year.

Of course, we pickle our gari at our restaurant, using vinegar, salt, and white granulated sugar. The reason the sourness is slightly strong is that it’s made to match the flavors of our nigiri. Commercial gari is too sweet and not edible. Saccharin usage is prohibited so that can’t be it, but it’s not the sweetness of sugar, either. I wonder what kind of sweetener they’re using.

To enjoy delicious nigiri, you eliminate the flavor, fat, and aroma of the one you just had with the spiciness of gari, and then wash the inside of your mouth with a very hot agari (green tea for eating sushi) that’s made with powdered tea. That’s the Edomae way.

Sencha (classic unshaded green tea), which is delicious at a lukewarm temperature, surely has a nice flavor and aroma, but the tepidness can bring out the fishiness. Agari has to be hot.

This is why an apprentice boy at a sushi restaurant keeps an eye on how fast the guests are sipping it, and if a cup is becoming empty, it’s refilled immediately. Using regular tea leaves would take too much time. If you make green tea by pouring hot water on expensive shincha (new tea) or gyokuro (“jade dew,” the finest of Japanese teas), it doesn’t taste good at all. This is why they came to use powdered tea, which turns into strong tea as soon as we pour hot water. Our powdered tea is from Kawane in Shizuoka Prefecture, and we get a direct shipment from the local producers.

Place only as much tea powder as necessary in the strainer and pour hot water over it. Since the agari goes into a teapot first, it won’t be scalding when it’s served into a cup.

It’s hard to make a sushi restaurant’s agari. It’s not good too strong. It’s not good too weak. This is why I always strictly lecture our young guys on how to make tea, saying, “You idiot! It’s not like if agari is bitter, then it’s good!” You can only use the powders once. If you reuse them a second time, it doesn’t taste good.

So if there are two customers, then we make exactly two servings of powdered tea, then discard it. This way, we can always serve delicious tea.

Put tea powder corresponding to the number of people in a tea strainer, and then pour hot water for that number of people into a teapot. I get mad when the young guys make tea indifferently without a mind to such basic common sense.

Say you’re serving agari to two customers. If an apprentice pours a lot of tea and there’s still half a teapot left, what happens to it? You have to make hot tea all over again. This is how it gets to, “You idiot!”

If I’m just having some tea, I wouldn’t holler even if it’s too strong. But with agari, it’s not like if it’s bitter, it’s good. Or if it’s hot, it’s good. The sourness of kohada (gizzard shad), the sweetness of the nitsume (reduction sauce) of anago (conger eel), the fat of otoro (fatty tuna), and the aroma of the ocean of nori maki—all of these need to be eliminated quickly with a sip or two of agari.

Some customers might like their agari bitter to the point that their faces twist. If a customer like that says, “Give me a bitter one,” then you should make and serve a really strong tea.

First off, for agari and other matters, sushi restaurants have procedures that are common sense. “If you’re aspiring to be a first-class pro, then follow that procedure.”

That is what I want to say.

A sushi chef in the habit of using the same amount of powdered tea for when there are two customers, five customers, or eight customers will create waste elsewhere too. And when he becomes independent, he’ll be in the red. But when it’s completely ingrained in you while you’re young that things belonging to other people are valuable, you’re bound to treat your own things as valuable when you become independent.

It’s not because I don’t want to waste powdered tea or because my wealth decreases a little that I get angry. It’s not that. It’s that if they keep doing such things, they’re never going to make it on their own. They’ll never make delicious nigiri.

When I was in second grade, at the age of eight, I went to serve at a kappo ryokan (an inn serving high-end traditional cuisine) in Futamatacho (present-day Tenryu) in Shizuoka Prefecture, and I worked as an assistant in the kitchen while I went to school. Apart from my stint at a munitions plant and enlistment during the war, ever since second grade I’ve always held a kitchen knife and was taught to treat other people’s things with care.

Even the young guys who work at our restaurant can’t possibly stay as apprentice boys forever. Their fate is to start their own places in the future or to inherit their fathers’ establishments. I want them to continue making nigiri in high spirits even when they’re over seventy like me, so being strict with them is a part of my job.

I’ll keep on scolding them for small mistakes if it has anything to do with sushi. No matter what they think of me, I’ll stay the stubborn scary pops of a sushi restaurant.

I’ve started thinking things like that, too, lately.

Jiro Ono roasts nori. Over blazing bincho charcoal, heat at nearly a right angle and swiftly turn over—a difficult technique.

Tekka Maki (tuna roll), (chutoro/medium-fatty tuna), May, Sado

Among Sukiyabashi Jiro orders, there are many for chutoro. Typically eaten dipped in shoyu (soy sauce) but served with nikiri brushed on it if a customer prefers.

Kyuri Maki (cucumber roll)

Two pieces of thin murokyuri (muro cucumber) as a core after removing the bumps, rolled with wasabi.

Oboro Maki (ground flesh roll)

The ebi oboro (ground flesh of shrimp) thin roll favored by regulars. Nice as a dessert of sorts to round out the meal.

Anakyu Maki

The tail flesh from simmered anago (conger eel) and cucumber as the core, rolled with wasabi and brushed with nitsume (reduction sauce) on the surface.

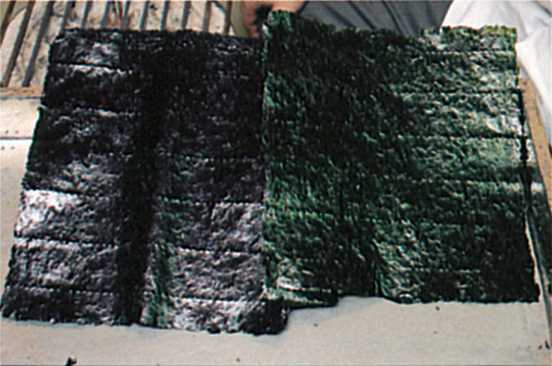

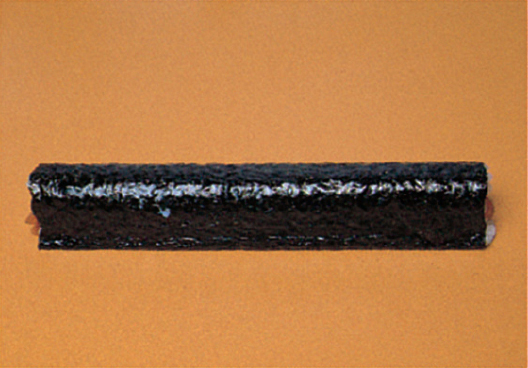

Left: nori upon stocking Right: grilled with bincho charcoal, turns vivid and aromatic

Kanpyo Maki (dried gourd roll)

Back in the day, nori maki (roll wrapped in seaweed) meant thin kanpyo maki. The umami of kanpyo worked on for two days has depth. Kanpyo maki are usually cut into four pieces, the other thin rolls in six.

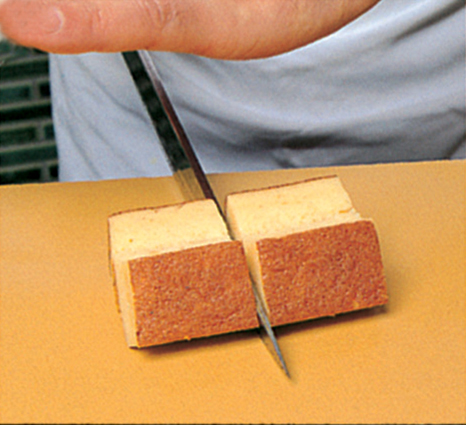

Sliced in two so it’s easier to eat.

For orders of just the tamagoyaki, it’s sliced into nigiri-dane size and brought to the counter.

Tamagoyaki (Japanese omelette)

Put a deep slit in tamagoyaki and make nigiri with it saddling. Less rice used than for other nigiri.

Ingredients: mirin (sweet rice wine), white granulated sugar, sea salt, kuruma ebi (prawn), and shiba ebi (shiba shrimp)

1

2 Remove shiba ebi’s heads, shells, and tails.

3

4 Peel shells off kuruma ebi as well. They can be leftover boiled ones.

5 Boil salt water, less salty than seawater, and put kuruma ebi in it.

6 Once surface of kuruma ebi has slightly colored …

7 Add shiba ebi.

8

9 Take out shiba ebi half-raw right before they are cooked through.

10 Drain water in colander.

11 Divide boiled shrimp into three batches and put in food processor.

12 Add a little water so it’ll be pasty, and switch on.

13 It turns into ground paste shortly.

15 Add white granulated sugar, for a plainer sweetness than regular sugar.

16 Add pinch of sea salt.

17 Completely dissolve sugar.

18 Once it starts to boil, lower heat and add ground ebi.

19 Stir with wooden spoon to avoid clumping.

20 Stir as if cutting with spoon so it doesn’t burn or become sticky.

21 Keep at it.

22 Keep roasting as long as it’s steaming.

23 Forty minutes after roasting, take off of heat and dissipate residual warmth by stirring with wooden spoon.

24 Done. Lasts about two weeks refrigerated.

1 Cut 400 g of dried kanpyo to the width of nori (dried seaweed).

2 Soak in water and restore.

3 Softens overnight.

4 Discard water and sprinkle two pinches of salt.

5 Massage with both hands until soft.

6

7 Rinse with water. Keep changing water to remove salt.

8 Put kanpyo in large pot, fill with water, and heat over high flame.

9 Stir once in a while to avoid tangling.

10 Check kanpyo while it’s boiling. It’s good when you can insert your nail.

11 Remove from heat and cool with water.

12 Squeeze lightly with both hands, trying not to squash kanpyo.

13 Drain in colander.

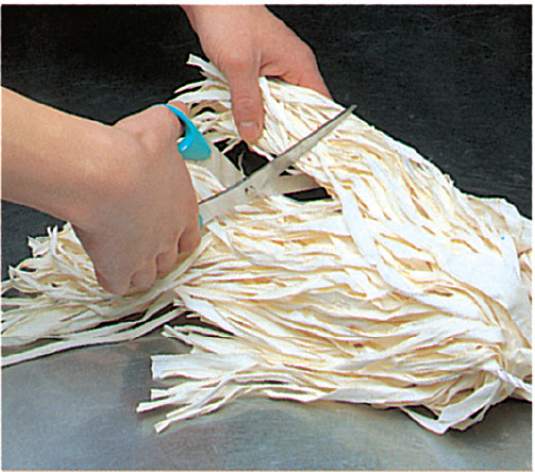

15 Now uniform in thickness, length, and width.

16 Put water and granulated white sugar in pot and bring to boil.

17 Add shoyu (soy sauce) when sugar has melted.

18 Bring back to a boil.

19 Unravel kanpyo and place in pot.

20 Spread and stew in just enough fluid to cover.

21 Once done, place in a colander to cool so it doesn’t get soggy.

22 Try to avoid uneven cooking.

23 Grab pot with both hands to toss kanpyo, instead of using saibashi (long chopsticks).

24 Simmer until all of the broth has soaked into kanpyo.

25 Once broth boils, flip kanpyo upside down.

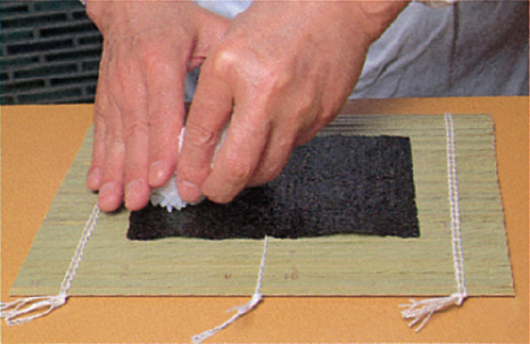

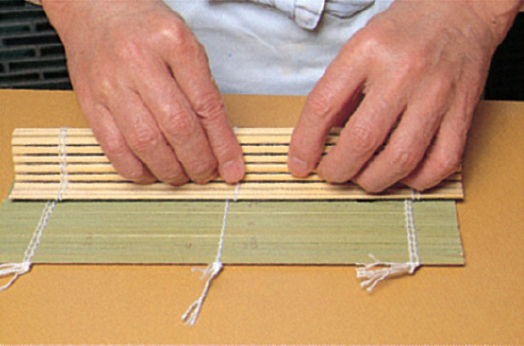

1 Place one roll worth of sushi rice on nori on top of makisu with the front side of nori facing down.

2 Press down while trying not to squash grains and spread sushi rice.

3 Spread it evenly into the edges.

4 Spread it toward you.

5 Leave about 5 mm on your side on nori.

6 Place kanpyo in the middle of sushi rice.

7 Press down kanpyo with middle fingers, lift up your side of makisu with thumbs, and roll in one go.

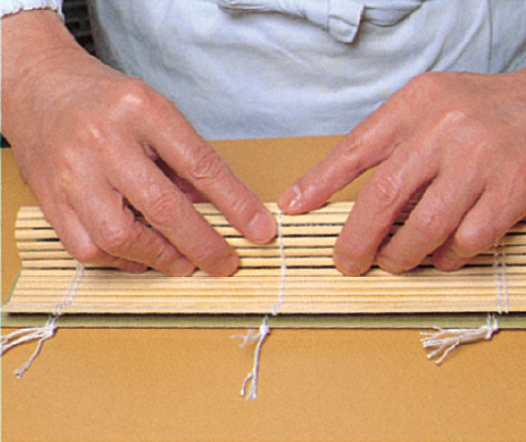

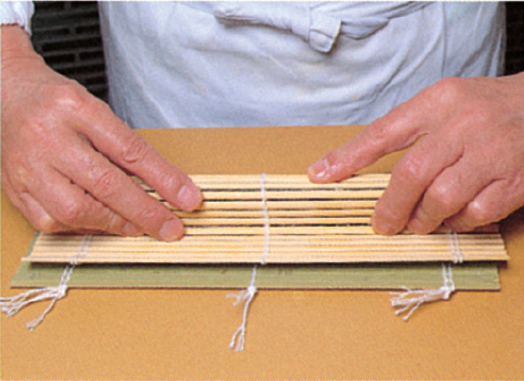

8 Tighten makisu without having it catch.

9

10 With where the nori meets on bottom, adjust shape into square.

11 Push both edges to keep contents from spilling.

12

13 Rolling done. Kanpyo maki is cut into four. Slice roll in half and then in half again.