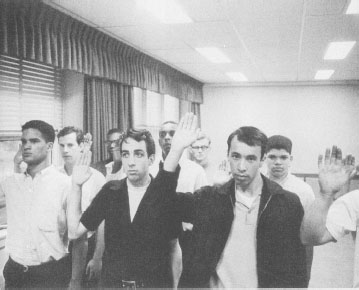

At an induction center, draftees join the U.S. Army.

These three pieces are meant to introduce the reader to the portrayal of the American soldier in Vietnam across time. Robin Moore’s The Green Berets appeared early in America’s involvement and cleaves to the government’s line; the soldiers are exemplary—strong, smart and heroic. O’Brien’s If I Die in a Combat Zone saw publication in the last year of the war, and reflects the confusion and idealism of that era. Appearing in the late seventies, O’Brien’s Going After Cacciato is more playful in its humor but equally damning. All three revolve around the soldier as hero and how he feels about the war.

Like the green recruit, the reader has to make sense of these conflicting views of Vietnam, learn the language, be careful of whom and what to trust. The various attitudes the authors, narrators, and characters take toward the war and how it’s being fought in these pieces seemingly can’t be reconciled. Likewise, precisely what constitutes a hero, a man, or a rational response is debatable. In their tone and focus, in their portrayal of Americans and Vietnamese, even in their charged descriptions of the settings, Moore and O’Brien appear to be covering completely different wars.

Robin Moore’s The Green Berets caused a sensation when it was first published in 1965. As he states in his preface, Moore, a free-lance journalist, wanted to write a nonfiction account of the U.S. Special Forces, but did such a good job of getting close to his subject that he suddenly knew too much sensitive information—so much that the Pentagon asked for a look at the manuscript and then told Crown, his publisher, that they couldn’t release the book as it was. Moore agreed to change facts and call the book a fiction (it’s not technically a novel, more a collection of related pieces). The effect of the Pentagon’s interference (and tacit admission that Moore knew the real truth) on the book’s sales is impossible to gauge, but the hardcover was licensed by the Book of the Month Club, and the paperback climbed the bestseller list. “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” a song inspired by the book and cowritten by Moore, shot to the top of the charts. In a neat tie-in, paperbacks from 1966 bear the face of the song’s co-author and singer, Sergeant Barry Sadler.

Later, John Wayne bought the movie rights to The Green Berets and directed and starred in the film version. Paradoxically, Lyndon Johnson’s administration directed the Army to give Wayne whatever technical support he needed, and they did. The resulting film (1968), which Gustav Hasford ridicules in The Short-Timers (1979), does in fact contain a scene in which the sun sets in the east. The movie was a tremendous flop, not because Wayne was so out of vogue but because in the three years since the book had come out, mainstream American attitudes toward the war had changed.

Tim O’Brien’s If I Die in a Combat Zone (1973) is nonfiction. O’Brien served as an infantryman in the Army’s Americal Division in 1970-71, and his book impressionistically describes his tour of duty from when he receives his induction notice until he returns home. Sections read like fiction, however, due to O’Brien’s novelistic technique; later he would become an acclaimed literary novelist, and some reprints of If I Die are actually mislabeled and shelved as fiction. The book was well received by critics; it was widely hailed as the best of the first prose efforts by veterans to describe the GI’s life in Vietnam. The piece included in this section details O’Brien’s indecisiveness in the face of his induction, a subject he addressed again nearly twenty years later in the award-winning short story “On the Rainy River” in The Things They Carried.

In 1978, O’Brien’s second novel, Going After Cacciato, established him as a major American writer. The book is a heavily sectioned metafiction. One narrative line follows Paul Berlin (a riff on Paul Baumer from All Quiet on the Western Front, and also a reference to the Allies’ final destination in World War II) and his squadmates as they chase a fellow grunt, Cacciato, across Asia and Europe. Cacciato (in Italian, the hunter or hunted) has quit the war and is walking to Paris. A second narrative line recounts the everyday boredom and terror of the war. The time scheme is jumbled (the war scenes jumping all over the place, the road to Paris linear), and the storylines speak to each other metaphorically without becoming obvious or heavy-handed. The two narratives are mediated by sections in which Paul Berlin is keeping a lonely watch in a tower; he may be dreaming the Cacciato story to temporarily escape the present. The novel is at once frightening and hilarious, as O’Brien leavens the tragedy of the war with zany plot twists and slapstick humor. Critics were amazed by his mix of the real and the fantastic and gave Going After Cacciato the National Book Award. The section that appears here shows Paul Berlin during his first few days in-country. It’s typical O’Brien, a combination of realism and telling metaphor.

The Green Berets is a book of truth. I planned and researched it originally to be an account presenting, through a series of actual incidents, an inside informed view of the almost unknown marvelous undercover work of our Special Forces in Vietnam and countries around the world. It was to be a factual book based on personal experience, firsthand knowledge and observation, naming persons and places. But it turned out that there were major obstacles and disadvantages in this straight reportorial method. And so, for the variety of reasons mentioned below, I decided I could present the truth better and more accurately in the form of fiction.

You will find in these pages many things that you will find hard to believe. Believe them. They happened this way. I changed details and names, but I did not change the basic truth. I could not tell the basic truth without changing the details and the names. Here’s why.

Many of the stories incorporate a number of events which if reported merely in isolation would fail to give the full meaning and background of the war in Vietnam. Saigon’s elite press corps, and such excellent feature writers as Jim Lucas of Scripps-Howard, Jack Langguth of The New York Times, and Dickey Chappell of The Reader’s Digest have reported the detailed incidents in the war. I felt that my job in this book was to give the broad overall picture of how Special Forces men operate, so each story basically is representative of a different facet of Special Forces action in wars like the one in Vietnam.

Also, as will be seen, Special Forces operations are, at times, highly unconventional. To report such occurrences factually, giving names, dates, and locations, could only embarrass U.S. planners in Vietnam and might even jeopardize the careers of invaluable officers. Time and again, I promised harried and heroic Special Forces men that their confidences were “off the record.” To show the kind of men they are, to present an honest, comprehensive, and informed picture of their activities, one must get to know them as no writer could who was bound to report exactly what he saw and heard.

Moreover, I was in the unique—and enviable—position of having official aid and assistance without being bound by official restrictions. Even though I always made it clear I was in Vietnam in an unofficial capacity, under these auspices much was shown and told to me. I did not want to pull punches; at the same time I felt it wasn’t right to abuse those special privileges and confidences by doing a straight reporting job.

The civic action portion of Special Forces operations can and should be reported factually. However, this book is more concerned with special missions, and I saw too many things that weren’t for my eyes—or any eyes other than the participants’ themselves—and assisted in too much imaginative circumvention of constricting ground rules merely to report what I saw under a thin disguise. The same blend of fact and “fiction” will be found in the locations in the book, many of which can be found on any map, while others are purely the author’s invention.

So for these reasons The Green Berets is presented as a work of fiction.

The headquarters of Special Forces Detachment B-520 in one of Vietnam’s most active war zones looks exactly like a fort out of the old West. Although the B detachments are strictly support and administrative units for the Special Forces A teams fighting the Communist Viet Cong guerrillas in the jungles and rice paddies, this headquarters had been attacked twice in the last year by Viet Cong and both times had sustained casualties.

I was finally keeping my promise to visit the headquarters of Major (since his arrival in Vietnam, Lieutenant Colonel) Train. I deposited my combat pack in the orderly room and strode through the open door into the CO’s office.

“Congratulations, Colonel.”

Lieutenant Colonel Train, looking both youthful and weathered, smiled self-assuredly, blew a long stream of cigar smoke across his desk, and motioned for me to sit down.

Major Fenz, the operations officer, walked into the office abruptly. “Sorry to interrupt, sir. We just received word that another patrol out of Phan Chau ran into an ambush. We lost four friendlies KIA.”

I sat up straight. “Old Kornie is getting himself some action.”

Train frowned thoughtfully. “Third time in a week he’s taken casualties.” He drummed his fingertips on the top of his desk. “Any enemy KIA, or captured weapons?”

“No weapons captured. They think they killed several VC from blood found on the foliage. No bodies.”

“I worry about Kornie,” Train said, with a trace of petulance. “He’s somehow managed to get two Vietnamese camp commanders relieved in the four months he’s been here. The new one is just what he wants, pliable. Kornie runs the camp as he pleases.”

“Kornie has killed more VC than any other A team in the three weeks since we’ve taken over here,” Fenz pointed out.

“Kornie is too damned independent and unorthodox,” Train said.

“That’s what they taught us at Bragg, Colonel,” I put in. “Or did I spend three months misunderstanding the message?”

“There are limits. I don’t agree with all the School teaches.”

“By the way, Colonel,” I said before we could disagree openly, “one reason I came down here was to get out to Phan Chau and watch Kornie in action.”

Train stared at me a moment. Then he said, “Let’s have a cup of coffee. Join us, Fenz?”

We walked out of the administration offices, across the parade ground and volleyball court of the B-team headquarters, and entered the club which served as morning coffeehouse, reading and relaxing room, and evening bar. Train called to the pretty Vietnamese waitress to bring us coffee.

There were a number of Special Forces officers and sergeants lounging around. It was to the B team that the A-team field men came on their way to a rest and rehabilitation leave in Saigon. Later they returned to the B team to await flights back to their A teams deep in Viet Cong territory.

Lieutenant Colonel Train had been an enigma to me ever since I first met him as a major taking the guerrilla course at Fort Bragg. His background was Regular Army. In World War II he had seen two years of combat duty in the Infantry, rising to the rank of staff sergeant when the war ended. Since his high-school record had been outstanding and his Army service flawless, he received an appointment to West Point. From the Point to Japan to Korea, Train had served with distinction as an Infantry officer, and in 1954 he applied for jump school at Fort Benning and became a paratrooper.

Almost nine years later, in line with Train’s interest in new developments, he had indicated that he would accept an assignment with Special Forces. I met him at Fort Bragg just after he had moved down Gruber Avenue from the 82nd Airborne Division to Smoke Bomb Hill, the Special Warfare Center.

It was obvious to those close to Train that he did not accept wholeheartedly the doctrines of unconventional warfare. But President Kennedy’s awareness of the importance of this facet of the military had made unconventional or special warfare experience a must for any officer who wanted to advance to top echelons.

As Train and I chatted and drank our coffee my interest grew in whether this dedicated officer was going to change and how he would operate in the guerrilla war in Vietnam.

“So you want to go to Phan Chau?” Train asked.

“I’d like to see Kornie in action,” I said. “Remember him at Bragg? He was the guerrilla chief in the big maneuvers.”

“Kornie has been one of the Army’s characters for ten years,” Train said sternly. “Of course I remember him. I’m afraid you’ll get yourself in trouble if you go to Phan Chau.”

“What do you mean by trouble?”

“I don’t want the first civilian writer killed in Vietnam to get it with my command.”

As I expected, Train was going to be a problem. “You think I stand a better chance of cashing in with Kornie than with some of the other A teams?”

Train took a long sip of coffee before answering. “He does damned dangerous things. I don’t think he reports everything he does even to me.”

“You’ve been here for three weeks, Colonel. The last B team had him four months. What did Major Grunner say about him?”

Fenz, a Special Forces officer for six years, concentrated on his coffee. Train gave me a wry smile. “The last B team was pretty unorthodox even by Special Forces standards. Major Grunner is a fine officer; I’m not saying anything against him or the way he operated this B detachment.” Train looked at me steadily. “But he let his A teams do things I won’t permit. And of course he and Kornie were old friends from the 10th Special Forces Group in Germany.” Train shook his head. “And that’s the wildest-thinking bunch I ever came across in my military career.”

Neither Fenz nor I made any reply. We sipped our coffee in silence. Train was one of the new breed of Special Forces officers. Unconventional warfare specialists had proven their ability to cope with the burgeoning Communist brand of limited or guerrilla wars so conclusively that Special Forces had been authorized an increase in strength. Several new groups were being added to the old 1st in Okinawa, 10th in Bad Tölz, Germany, and the 5th and 7th at Fort Bragg.

New officers were picked from among the most outstanding men in airborne and conventional units. Since every Special Forces officer and enlisted man is a paratrooper, it was occasionally necessary to send some “straight-leg” officers to jump school at Fort Benning, Georgia, before they could attend the Special Warfare School at Fort Bragg prior to being assigned to a Special Forces group.

This new group of basically conventional officers in Special Forces were already beginning to make their influence felt early in 1964. Lieutenant Colonel Train was clearly going to be a hard man to develop into a “Green Beret—All the Way!”

I broke the silence, directing a question at Major Fenz. “When can you get me out to Phan Chau?”

Fenz looked to Train for guidance. Train smiled at me wryly. “We’ve got to let you go if you want to. But do us all a favor, will you? Don’t get yourself killed. I thought you’d had it on the night jump in Uwarrie …”

He turned to Fenz and told him the story. “They dropped our teams together on the ten-day field training exercise.”

Fenz nodded; the ten-day field training exercise was a bond shared by all Special Warfare School graduates.

“The School picked us a drop zone in Uwarrie National Forest near Pisgah—that was something else. It was a terrible night,” Train recalled. “Cold. And the wind came up before we reached the DZ. An equipment bundle got stuck in the door for six seconds so we had to make two passes. Our friend here was held at the door by the jump master and was first man out on the second pass. We were blown into the trees over a mile from the DZ. I got hung up, had to open my emergency chute and climb down the shroud lines to get on the ground. We had three broken legs and several other injuries on that DZ.”

Train looked at me and smiled. “Our civilian, of course, came out best. Landed in a field the size of the volleyball court, threw his air items in the bag and helped pull his team together.”

I looked out the window across the rice paddies where every peasant could be and probably was a Viet Cong. “At least they didn’t have shit-dipped pungi stakes waiting for us in North Carolina,” I said.

Train frowned briefly at my language. “I guess you and Kornie will get along fine, at that. As I remember, you pulled a few tricks on that exercise that weren’t even in the books.”

Fenz took this as his cue to volunteer the information that there was an Otter flying down to Phan Chau that afternoon with an interpreter to replace the one killed a few days before on patrol.

“You might as well take it,” Train said. “How long do you want to stay?”

“Can’t I just play it by ear, Colonel?”

“Certainly. If it looks like there’s going to be serious trouble I’ll get you evacuated.”

“Negative! Please?”

Train stared at me; I met the look. Train gave a shrug. “OK, I’ll go along with you, but I still don’t—”

“No sweat. I don’t want to get myself greased any more than you do.”

“OK, get your gear together. Got your own weapon?”

“If you could lend me a folding-stock carbine and a few banana clips, that’s all I need.”

“Fenz, can you fix him up?”

“Yes, sir. The Otter takes off at 1300 hours.”

“One thing,” Train cautioned. “Kornie is upset because we transferred two companies of Hoa Hao troops from his camp on orders from the Vietnamese division commander, General Co. You know about the Hoa Hao?”

“They’re supposed to be fierce fighters, aren’t they?”

“That’s right. They’re a religious sect in the Mekong Delta with slightly different ethnic origins from the Vietnamese. General Co didn’t like having two companies of Hoa Hao fighting together.”

“You mean with coup fever raging, he was afraid the Hoa Hao might get together and make a deal with one of his rival generals?”

“We try to keep out of politics,” Train said testily. “General Co’s reasoning is not my concern.”

“But it would concern Kornie to find himself on the Cambodian border in the middle of VC territory suddenly minus two companies of his best fighting men.”

Train snorted in exasperation. “Just don’t take Komie’s opinions on Vietnamese politics too seriously.”

“I’ll use discretion in anything I say,” I promised.

“I hope so.” It sounded like a threat.

Looking down at the sere-brown rice paddies, I felt a sense of quickening excitement as the little eight-place single-engine plane closed on Phan Chau in a hilly section along the Cambodian border. Across from me sat the thin, ascetic-looking young Vietnamese interpreter.

I thought of Steve Kornie. His first name was Sven actually. He was, at forty-four, a captain, as compared to Train, who was a lieutenant colonel at thirty-nine.

Kornie, originally a Finn, fought the Russians when they invaded his native land. Later he had joined the German Army and miraculously survived two years of fighting the Russians on the eastern front. After the war came a period in his life he never talked about. His career was re-entered on the record book when, under the Lodge Act of the early fifties, which permitted foreign nationals who joined in the United States Army in Europe to become eligible for U.S. citizenship after five years service, Kornie enlisted.

In a barroom brawl in Germany in 1955, Kornie and some of his more obstreperous GI companions had committed the usually disastrous error of tangling with several soldiers wearing green berets with silver Trojan horse insignias on them. The blue-eyed Nordic giant, after decking twice his weight in berets, finally agreed to a truce.

Suspiciously he allowed these soldiers, who in spite of their alien headdress proclaimed themselves Americans, to buy him a drink. In his career with several armies he had never fought such tough barehanded fighters. As the several victims of Kornie’s fists and flathanded chops came to, shook their heads, found their berets and replaced them on their heads, it became clear to Kornie that they were asking him to join their group. To his surprise and horror he discovered that one man he had knocked over the bar was a major.

Before the evening was over Kornie discovered the existence of the 10th Special Forces Group at Bad Tölz, had given the major his name, rank and serial number, and had been promised that he would soon be transferred to the elite, highly trained, virtually secret unit of the U.S. Army to which these men in green berets so proudly belonged.

When Special Forces realized the extent of Sven Kornie’s combat experience and language capabilities, the commanding officer at Bad Tölz believed his claim that he had gone to the military college for almost three years in Finland, although his academic records had been lost in the war and he could not prove his educational qualifications. Kornie was sent to Officer Candidate School, and Special Forces was waiting to reclaim him immediately upon graduation. He performed many covert as well as overt missions in Europe as a Special Forces officer, several times on loan to the CIA, and finally, having reached the grade of captain, he was shipped to the 5th Special Forces Group at the Special Warfare Center, Fort Bragg.

In his early forties he knew his chances of ever making field grade were slim. For one thing, while in uniform he had killed a German civilian he knew to be a Russian agent with a single punch. Extenuating circumstances had won him an acquittal at his court-martial; nevertheless the affair was distasteful, particularly to conservative old line officers on promotion boards. There was also Kornie’s inability to prove any higher education.

Sven Kornie was the ideal Special Forces officer. Special Forces was his life; fighting, especially unorthodox warfare, was what he lived for. He had no career to sacrifice; he had no desire to rise from operational to supervisory levels. And not the least of his assets, he was unmarried and had no attachments to anyone or anything in the world beyond Special Forces.

My thoughts of Kornie and speculations as to what fascinating mischief he would be up to were interrupted by the interpreter.

“Are you posted to Phan Chau?”

I shook my head, but he had an explanation coming. I wore the complete Special Forces uniform, the lightweight jungle fatigues and my highly prized green beret which an A team had given me after a combat mission.

“I will visit Phan Chau for maybe a week. I am a writer. A journalist. You understand?”

The interpreter’s face lit up. “Ah, journalist. Yes. What journal you write for?” Hopefully: “Time magazine? Maybe Newsweek? Life?”

He couldn’t disguise his disappointment when he learned what a free-lance writer was.

We were getting close to Phan Chau. I recognized the area from several parachute supply drops I had flown to familiarize myself with the terrain.

The little Otter began circling. Only a few miles off I could look into Cambodia, the border running down the middle of the rough, rocky terrain. A dirt landing-strip appeared below and in moments the plane was bumping along it.

I threw my combat pack out on the ground, and when the small plane had come to a complete stop jumped out after it. I saw a green beret among the camouflage-capped Vietnamese strike-force troopers milling around, and went up to the American sergeant and told him who I was. He recognized my name and mission, but I was surprised to hear Kornie wasn’t expecting me.

“Sometimes we can’t read the B team for half a day,” the sergeant explained. “The old man will be glad to see you. He’s been wondering when you were coming.”

“I guess I missed some action this morning.”

“Yeah, it was a tough one. Four strikers KIA. We usually don’t get ambushed so close to camp.” The sergeant introduced himself to me as Borst, the radio operator. He was a well-set young man, his cropped hair below the green beret yellow, and his blue eyes fierce. I wondered if Kornie had collected an all-Viking A team. Anything unusual, with flair and color, would be typical Kornie.

“The old man is working out some big deal with Sergeant Bergholtz, he’s our team sergeant, and Sergeant Falk, intelligence.”

“Where’s Lieutenant Schmelzer?” I asked. “I knew him at Bragg last year while you were all in mission training.”

“He’s still out with the patrol that was ambushed. They sent back the bodies and the wounded, and then kept going.”

Sergeant Borst picked up my combat pack, carried it to the truck, and threw it in back with the strikers and the new interpreter. He motioned me into the front seat, looked behind to make sure the mounted .30-caliber machine gun was manned, and drove off as soon as the Otter was airborne.

The low, white buildings with dark roofs which rose above the mud walls of Phan Chau, and the tall steel fire-control tower were visible from the airstrip. Beyond them, directly west, loomed the rocky foothills which spilled along both sides of the Vietnam-Cambodia border. There were more hills and a scrub-brush jungle north of Phan Chau. To the south the land was open and bare. The airstrip was only a mile east of the camp.

“This the new camp?”

“Yes, sir,” Borst answered. “The old one next to the town of Phan Chau was something else. Hills on all sides. We called it little Dien Bien Phu. Here at least we’ve got some open fields of fire and the VC can’t drop mortar fire on us from above.”

“From what I hear, you’re out of that old French camp just in time.”

“That’s what I figure. They’d clobber us in there. When this one is finished we’ll be able to hold off about anything they can throw at us.”

As we drove into the square fort, with sandbagged mud walls studded with machine-gun emplacements and surrounded with barbed wire, I could see men working on the walls and putting out more barbed wire. “Do you still have much work to do?”

“Quite a bit, sir. We’re sure hoping we don’t get hit in the next few days. The camp isn’t secure yet.”

Borst stopped before the Vietnamese Special Forces headquarters to let off the strikers and the new interpreter, and then drove me another twenty feet to a cement-block building with a wooden roof. He pulled to a stop and jumped out. Borst beat me inside and I heard him announce me.

It took a moment for my eyes to get used to the cool interior grayness after the hot, bright sunlight. The big form of Sven Kornie came toward me. He had a large grin on his lean, pleasant face and his blue eyes snapped. His huge hand enveloped mine as he welcomed me to Phan Chau. He introduced me to Sergeant Bergholtz, and I sensed my guess was correct that a Germanic-Viking crew had indeed been transported intact to the Vietnam-Cambodia border.

“Well, well,” Kornie boomed cheerfully. “You come here at a dangerous time.”

“What’s happening?”

“By God damn! Those Vietnamese generals—stupid! Dangerous stupid. Two hundred fifty my best men that sneak-eyed yellow-skin bastard corps commander take out of here yesterday—and our big American generals? Politics they play while this camp gets zapped.”

“What are you talking about, Steve?”

“Two hundred fifty Hoa Hao fighting men I had. The best. Now General Co decides he don’t want any Hoa Hao companies fighting together because maybe they get together under their colonel and pull another coup. So he breaks up the best fighting units in the Mekong Delta. God damn fool! And Phan Chau, what happens? We get more Vietnamese strikers we don’t know if they fight for us or VC. You better go back to the B team,” he finished lugubriously.

“Too late now,” I said. “What action have you got going?”

“Two actions. The VC got one action and we got one. Tell him, Bergholtz.”

The team sergeant began his briefing. “The VC have been making ladders for a couple of weeks now in all their villages. They’re also making caskets. That means they figure on hitting us sometime soon. The ladders they use to throw across the barbed wire and the mine fields and later as stretchers to carry away the dead and wounded. The VC fight better when they know they’re going to get a funeral and a nice wood box if they’re killed. They see the coffins, it makes their morale go up.”

“We are not ready for attack,” Kornie said, “so it probably comes soon.”

“What’s Schmelzer’s patrol doing?”

Kornie’s deep laugh boomed out. “Schmelzer is looking for KKK.”

“KKK? I thought we were in South Vietnam, not South Carolina.”

“The KKK are Cambodian bandits. They fight only for money. They are very bad boys. Tell him, Bergholtz.”

“Yes, sir.” The team sergeant turned his rugged face to me. “The KKK—that’s what everyone calls them—live around these hills. They even attack our patrols for the weapons if they are strong enough. We figure the ambush today may have been KKK. Last week four Buddhist monks went through here to Cambodia to buy gold leaf for their temple. All the local Buddhists kicked in to buy the stuff. You can’t buy gold in Vietnam.” Bergholtz paused. “We told the monks they better stay home but they said Buddha would protect them.”

Kornie finished the story. “Three days ago I was leading a patrol in KKK area. We find the monks. They are lying on the trail, each has his head under his left arm. The KKK got them and their gold.”

“And Schmelzer is going to get the KKK?” I asked.

“He is only trying to locate them. Maybe they will be useful to us on the operation we plan.”

I gave him full attention, unslinging my carbine and leaning it against the wall.

“We get tired of the VC hitting us and running across the border to Cambodia where we can’t get them,” Kornie said. “This team of mine, we got only one month left before we go back to Fort Bragg. Garrison duty.” Kornie growled. “Two cowardly Vietnamese camp commanders in a row we get. Sometimes is a week between good VC contact.”

“But this time I hear you have a good counterpart.”

“This one is good,” Kornie conceded. “He maybe don’t like patrols himself, but if the Americans want to kill themselves and only a reasonable number of strikers, that’s our business by him. Come, follow me. I will show you what we are going to do.” He led me out of the teamhouse, down the mud road and on past several cement barracks with wood and thatch roofs. We stopped at one and a guard saluted. His dark skin and imprecise features marked the striker in tiger-stripe camouflage as a Cambodian. Kornie returned the salute and walked inside. There must have been about 50 men in the barracks. They were cleaning their rifles, making up packs, and apparently readying themselves to go out on a combat operation.

“These Cambodes good boys,” Kornie boomed. “Loyal to the Americans who pay them and feed them. Not like the KKK.”

The Cambodes evidently liked the captain, for Kornie lustily shouted some indistinguishable words and got back an enthusiastic response. “I ask them if they are ready to kill Communists anywhere, even in Cambodia. They are ready.” He gave them a cheerful wave and we left.

“Let’s go to the radio room and see what we hear from Schmelzer.”

Borst was at the radio, earphones on, scribbling on a sheet of paper in front of him. He looked up as Kornie came in.

“Sir, Lieutenant Schmelzer is standing by on voice.”

“Good!” Kornie exclaimed, taking the mike. “Handy, Handy,” he called. “This is Grant, Grant. Come in Handy.”

“Grant, this is Handy,” came back over the receiver. “Made contact with bandits at BP 236581.” On the map above the radio Kornie located the position of his executive officer from the coordinates. It was eight miles north of Phan Chau, almost straddling the border.

Schmelzer continued. “Our assets now having friendly talk with bandits. Believe you can go ahead with operation. That is all. Handy out.”

“Grant out,” Kornie said, putting down the mike. He turned to me. “Our plans are coming along well. Now if the Viet Cong give us tonight without attacking, we will buy another few days to finish the camp’s defenses. Then”—Kornie grinned—“they can throw a regiment at us and we kill them all.”

Kornie led the way back to the operations room where Sergeant Bergholtz was waiting for him. As we walked in the sergeant said, “Falk just got another agent report. There are about 100 VC hiding in Chau Lu, resting and getting food. Less than half live there, the rest must be hard-core just come over from Cambodia.”

“That is good, that is good,” Kornie said, nodding. “Now, I will explain everything. Here.” He pointed to the map. “You see the border running north and south? Our camp is three miles east from Cambodia. Four miles north of us is this nasty little village of Chau Lu right on the border near which we were ambushed this morning. Four more miles north of Chau Lu, still on the border, is where Schmelzer is right now, talking to the KKK.”

“I’m with you so far,” I said.

“Good. Now, in Cambodia, exactly opposite Chau Lu, ten miles in is a big VC camp. They got a hospital, barracks, all the comforts of a major installation. The attack on us will be launched from this big Communist camp. The VC will cross the border and build up in Chau Lu, like they do now. When they’re ready, they hit us. If we try to hit their buildup on our side of the border they only got to run a hundred meters and they’re back in Cambodia where we can’t kill them. Even if we go over after them they pull back to their big camp where we get zapped and cause big international incident.”

Kornie watched me intently for a reaction. I began to get a vague idea of what he had in mind. “Keep talking, Steve. I’ve always wanted to go inside Cambodia.”

The big Viking laughed hugely. “Tonight, my Cambodes, 100 of them, cross the border and take up blocking positions two miles inside Cambodia between Chau Lu and the big VC camp. There is a river parallel to the border in there. My Cambodes put their backs to the river and ambush the VC who are running from Chau Lu, which we attack just before sunrise tomorrow morning. At the river my boys can see and kill any VC from the main camp who try to cross it and get behind them.”

I had to laugh, the thinking was so typically Kornie, and just what Lieutenant Colonel Train, who was so scrupulous about international politics, was afraid of.

Kornie continued. “If the VC are suddenly cut to little pieces right where they think they are safe, in Cambodia, they will be careful for a while. Maybe they think they get attacked again in this sanctuary our politicians give them.”

“They’ll know you did it, Steve,” I said soberly. “And then they’ll raise international hell.”

“Yes, they know we do it,” Kornie agreed. “This will scare them. But international incident? No. They don’t prove we have anything to do with it.”

“Well, somebody had to ambush those VC,” I pointed out. “If there’s a bunch of shot-up bodies nobody’s going to believe Cambodian-government troops did it to their Communist friends.”

Kornie’s blue eyes sparkled with humor and excitement. “Oh yes. But we got what you call, fall guys. Come, let’s go back to the radio room.”

Just after dark I accompanied Kornie and Sergeant Bergholtz as they led the company of cocky, spoiling-for-action Cambodians to the border where a rally point was established with a squad guarding it. This was the point at which the Cambodians would cross back to the Vietnam side of the border after their mission. Kornie wanted Bergholtz and every one of his Cambodians to be familiar with the place. It was at the base of one of the many hills along this section of the border. For positive identification Kornie sent another squad to the top of the hill. There they would start firing flares a few minutes after the shooting started and keep it up until all the Cambodians had found their way back to the rally point and were accounted for.

With the return point on the border clearly defined, Kornie, Bergholtz, I, and the company of Cambodians stealthily moved northward on the Vietnam side of the border. We carefully gave the Viet Cong village of Chau Lu a wide berth an hour later and kept pushing north two more miles. Halfway between Chau Lu and the KKK camp we stopped.

Kornie shook Bergholtz by the hand and silently clapped him on the back. Bergholtz made a sign to the Cambodian leader and they started due west across the ill-defined border into Cambodia. Kornie watched them until they melted into the dark, rugged terrain. In two and a half miles they would come to the river and follow it back south until they were squarely between Chau Lu and the Viet Cong camp. They would straddle the east-west road and bridge connecting the two Communist bases and set up blocking positions.

Kornie and I and a security squad walked the six miles back to camp, arriving about 3:00 A.M. We made straight for the radio room and Kornie called Schmelzer.

Schmelzer was handling his operation well. Fifty KKK bandits were already crossing into Cambodia. They would penetrate a mile and staying that far inside Cambodia walk south until they were opposite Chau Lu. Here, according to instructions, they would stop until sunrise. Then they would proceed another mile south. At the point where a needle of rock projected skyward they would cross back into Vietnam and report all they had observed to the Americans.

The KKK leader realized that the Americans had to know what the Viet Cong were doing. He also knew they couldn’t send patrols across the border to find out. He was glad to mount an easy reconnaissance patrol in return for the equivalent of $10 a man plus five rifles and five automatic weapons.

Half the agreed-upon money and weapons Schmelzer had already presented to the KKK leader at the time his men began crossing the border. The balance would be forthcoming the moment the men crossed back into Vietnam at the needle-shaped rock and gave their reports.

In the radio room Kornie chortled as his operation began to tighten. “Schmelzer is good boy,” he said. “Takes guts to deal with KKK. If they think for a minute they can take Schmelzer and his men, they do it.”

“Aren’t you afraid they’ll use those automatic weapons against you some day?” I asked.

Kornie shrugged. “Most of those KKK and their weapons will never get back from this mission.”

He looked at his watch. It was 4:00 A.M. Kornie smiled at me and patted my shoulder. “Now is the time to start out for Chau Lu. We will drive the VC straight into the KKK at 0545, and Bergholtz and the Cambodes will cut both the KKK and VC to pieces and be out of there by 0600 hours.” His laugh resounded in the radio shack. “Give me just a few more days and a regiment couldn’t overrun Phan Chau.”

There was a snapping of static and then the radio emitted Schmelzer’s voice. “Grant, Grant, this is Handy. Come in, Grant.”

Kornie picked up the mike. “This is Grant. Go ahead, Handy.”

“Last of the bandits across. We are ready to carry out phase two. Is 0545 hours still correct?”

“Affirmative, Handy. But wait for us to start our little party off.”

“Roger, Grant. We will be in position. When you open up, we’ll let go too. Leaving now. Handy out.”

“Grant out,” Kornie said into the mike and put it down. He walked out of the radio room, and on the parade ground we could sense more than see the company of Vietnamese strikers. Two Vietnamese Special Forces officers, the camp commander, Captain Lan, and his executive officer were standing in front of the company of civilian irregulars waiting for Kornie. They saluted him as he stood in the light flooding from the door of the radio room.

Kornie saluted back. “Are you ready to go, Captain Lan?”

“The men are ready,” the Vietnamese commander said. “Lieutenant Cau and Sergeant Tuyet will lead them. I must stay in camp. Maybe B team need talk to me.”

“Very good thinking, Captain,” Kornie complimented his counterpart. “Yes, since I go out, very good you guard camp.”

Pleased, Captain Lan turned his men over to Kornie and departed. “Lieutenant Cau, let’s get these men on the move,” Kornie urged. “You know the objective.”

“Yes, sir. Chau Lu.” In the dim light from the radio shack Kornie and I could just make out the broad grin on Cau’s face. “We will clobber them, sir,” he said, proud of his English slang.

Kornie nodded happily. “Right. We massacre them.” To me he said, “Cau here is one of the tigers. If they had a few hundred more like him we could go home. He went through Bragg last year. Class before yours, I think.”

For the second time that night we started north toward Chau Lu. Kornie seemed to be an inexhaustible tower of energy. Walking at the head of the column he kept up a brisk pace, but we had to stop frequently to let the short-legged Vietnamese catch up. It took exactly the estimated hour and a half to cover the almost five miles to the positions we took up south and east of the VC village. At 5:45 A.M. two companies of strikers were in place ready to attack Chau Lu. Schmelzer’s men were ready to hit from the north.

Lieutenant Cau glanced from his wristwatch to the walls of the village one hundred yards away. He raised his carbine, looked at Kornie who nodded vigorously, and blasted away on full automatic. Instantly from all around the village the strike force began firing. Lieutenant Cau shrilled his whistle and his men moved forward. Fire spurted back at us from the village, incoming rounds whining. Instinctively I wanted to throw myself down on the ground but Cau and his men advanced into the fire from the village shouting and shooting. From the north Schmelzer’s company charged in on the village also. Within moments the volume of return fire from the Viet Cong village faded to nothing.

“They’re on their way now, escaping to their privileged sanctuary,” Kornie yelled. “Cease fire, Lieutenant Cau.”

After repeated blasts on the whistle the company gradually, reluctantly, stopped shooting. Schmelzer’s people had also stopped and there was a startled silence.

The two companies entered the village and routed the civilians out of the protective shelters dug in the dirt floors of their houses.

Kornie looked at Lieutenant Cau in the pale light of dawn. Disappointment was clearly written on his face as his men herded civilians into the center of town. Cau had not been told about the rest of his operation. After a few minutes of preliminary questioning Cau came to Kornie.

“The people say no men in this village. All drafted into the Army. Just old men, women, and children.”

Kornie glanced at his watch. 5:53. His infectious grin puzzled the Vietnamese officer. “Lieutenant Cau, you tell the people that in just a few minutes they’ll know exactly where their men are.”

Cau looked at Kornie, still puzzled. “They run across into Cambodia.” He pointed across the town toward the border. “I would like to take my men after them.” He smiled sadly. “But I think maybe I do my country more good if I am not in jail.”

“You’re so right, Cau. Now search the town. See if you can find any hidden arms.”

“We are searching, sir, but why would the VC hide guns here when just two hundred meters away they can keep them in complete safety.”

Before Kornie could answer, a sudden, steadily increasing crackling of gunfire resounded through the crisp air of dawn. Kornie cocked an ear happily. The noise became louder and more scattered. Automatic weapons, the bang of grenades, sharp rifle reports and then the whooshing of hot air followed by the shattering explosions of recoilless-rifle rounds echoed up and down the border.

“Bergholtz is giving them hell,” Kornie shouted gleefully, thumping me on the back. I tried to get out from under his powerful arms. “My God! I wish I was with Bergholtz and the Cambodes.” A sharp burping of rounds which suddenly terminated with the explosion of a grenade caused Kornie to yell at Schmelzer, who was approaching us.

“Hey, Schmelzer. That was one of those Chinese machine guns we gave the KKK. Did you hear it jam?”

“I heard a grenade get it,” Schmelzer answered.

The faces of the old men, women, and children were masks of sudden fear, confusion, and panic. They stole looks at we three Americans and a slow comprehension began to show in their eyes. Then their features twisted into sheer hatred.

The fire-fight raged for fifteen minutes as the sun was rising. To the south a steady series of flares spurted from the top of the hill, marking the rally point where Bergholtz and his Cambodians would cross back into Vietnam.

Kornie took a last look around the village. “OK, Schmelzer, let’s go pay off the KKK. Give the ones that come back a nice bonus. If they complain about being attacked by their good friends the VC, tell them”—Kornie grinned—“we’re sorry about that.”

He gave his executive officer a hearty slap on the bad that would have sent a smaller man tumbling. “Be sure that your whole company has weapons at the ready,” Kornie cautioned. “They might think we slipped it to them on purpose and do something naughty.” Kornie was thoughtful for a moment. “Maybe I take a platoon of Lieutenant Cau’s men and go with you. If we meet no trouble I’ll go on south, find Bergholtz, and see how he did.”

Leaving Lieutenant Cau the dreary task of searching the village and questioning the inhabitants, we started south. It was only a mile walk to the needle of rock, and a band of about 15 KKK were already there. Schmelzer, well covered by a platoon of his best riflemen, approached the KKK leader who was dressed in khaki pants and a black pajama shirt—two bandoleers of ammunition crossing his shoulders. An interpreter walked beside Schmelzer, and Kornie and I edged forward, being careful not to get between our riflemen and the KKK. Both Schmelzer and Kornie gave the thoroughly mean- and suspicious-looking bandit leader friendly smiles. Schmelzer reached inside his coat and produced a thick wallet. The sight of the money seemed to have a slightly calming effect on the KKK chief.

“When all your men are back I give you the other 25,000 piastres,” Schmelzer said, counting the money.

The translator came back with the chief’s retort. “Maybe my men do not all come back. Who they fight over there?”

“The VC of course,” Schmelzer answered innocently. “Your men are friends of the Americans and Vietnamese aren’t they?”

The KKK chief scowled, but he did not take his eyes off the money as Schmelzer counted it out. There was an uncomfortably long wait in a highly hostile atmosphere until the rest of the KKK started to arrive at needle rock from across the border.

Kornie and Schmelzer impassively watched the wounded, bloody men straggling in. Those who couldn’t walk were helped by others. One or two carried shattered bodies.

“Remember how those monks looked with their heads under the arms?” Kornie asked Schmelzer, who nodded grimly.

Of the 50 KKK who had gone out, 30 were alive, only 10 unwounded. They brought back only six bodies.

The KKK chief, regarding his broken force, turned toward Kornie, his hand twitching at the trigger guard of the Chinese submachine gun Schmelzer had given him.

There was no doubt that the KKK knew they had been tricked by the Americans. Still, Kornie and Schmelzer played the game, expressing condolences at the number of KKK killed and wounded.

“Tell the chief,” Schmelzer said, “we will pay a bounty of 500 piastres for each VC killed.”

The chief’s visage grew blacker as he walked to the survivors. The interpreter listened, turning his head sidewise to the KKK leader.

“He says,” came the translation, “that his men were attacked from two directions at once. He says that first the shooting came from inside Cambodia and then from the VC running from the attack we made on Chau Lu. His men fired in both directions but killed mostly the men running from Chau Lu because they were easier to see. He says he wants to be paid for killing 100 VC. His men had no time to take ears or hands for proof. He says we tricked him, we did not tell him about Chau Lu.”

“Tell him it was a very unfortunate misinterpretation of orders,” Kornie said. “We’ll pay him 500 piastres each for 25 VC dead, and we’ll give him a 1,000 piastres for each of the men he lost KIA.”

Schmelzer’s company of Vietnamese irregulars sensed the hatred of the KKK for us and shifted their weapons uneasily; but the chief was in no position to instigate violence. His eyes glowed malevolently as he estimated our strength and then accepted the deal.

“Why do you pay him anything?” I asked. “He’s going to try and get you anyway first chance that comes along.”

Kornie grinned. “If a battle across the border is reported I think Saigon would accept the proposition that I paid a bunch of Cambodian bandits to break up the VC in Cambodia long enough to make my camp secure.” To Schmelzer he said, “Get receipts from the leader for the money and get photographs of him accepting it.”

The interpreter called to Kornie as he and I were about to leave with a security platoon. “Sir, KKK chief say he lose three automatic weapons and two rifles. He want them replaced.”

“You tell him I’m sorry about that. We gave him the guns. If he can’t hold on to them, that’s his fault.” Kornie waited until his words had been translated. He stood facing the chief, staring down bleakly at the sinister little brown bandit. The KKK chief realized he had been accorded all the concessions he could expect and avoided Kornie’s steady gaze. Schmelzer and his sergeant continued counting out the money for the Cambodian bandits.

The groans of the wounded men attracted Kornie’s attention. He walked over to where they were sitting or lying in the dirt. After examining some of the more seriously wounded he straightened up.

“Schmelzer, before you go, ask the Vietnamese medics to help these men. They may be bandits fighting us tomorrow, looting merchants and monks the next day, but they do us a big service today—even though they do not mean to.

“And when you finish here go directly back to Phan Chau. And keep an alert rear guard all the time.” Kornie grinned goodnaturedly at the scowling group around the KKK leader. “Those boys have big case of the ass with us.”

Kornie and I and his platoon left the needle-rock rendezvous and walked south for two miles to our Cambodians’ rally point, covering the distance in less than an hour.

Sergeant Falk and his security squad were just welcoming the returned Cambodians as we arrived. Sergeant Ebberson, the medic, had the tools of his trade spread out and ready. Stretchers and bearers were waiting.

Bergholtz, grinning from ear to ear, was waiting for us. “How goes, Bergholtz?” Kornie called, striding toward his big sergeant.

“We greased the shit out of them, sir,” Bergholtz cried joyfully. “These Cambodes never had so much fun in their lives.” The little dark men in tiger-striped suits bounced around happily, chattering to each other and displaying bloody ears, proof of the operation’s success.

“How many VC killed in action?”

“Things were pretty confused, sir. From Chau Lu the VC walked right into us and the KKK. There was a lot of shooting going on in front of us. I think they killed as many of each other as we did in. Then the KKK and the VC both concentrated on us and our Cambodes flat-ass massacred everything that lived in front of us. If there aren’t 60 dead VC lying out there I’ll extend another six months. We lost a few dead and maybe 8 or 10 wounded but we didn’t leave a body behind, sir.”

Kornie’s eyes glistened with pride. “By God damn, Bergholtz. We got the best camp in Vietnam. I volunteer us all to stay another six months. What do you say?”

“Well, sir, we still have one more month left of our tour to burn the asses off the VC. This operation we made it out just in time. When we moved the VC were barreling down the road from the big camp, shooting like mad.”

Kornie watched as two Cambodians deposited the gore-smeared body of a comrade on the ground beside two other bodies. Sergeant Ebberson was working on the wounded as they were dragged and assisted in. Even the wounded were in good spirits. They had won a victory and the fact that it had been won by going illegally across the border only made the triumph more satisfying.

Kornie threw a massive arm around my shoulder, another around Bergholtz, and started us in the direction of Phan Chau. “Let’s go back, men. Maybe the VC call Phnom Penh and the Cambodian government will be screaming border violation. We must get immediate report to Colonel Train.”

We walked at the head of the security platoon for a few minutes and then Kornie said to me, “You are friend of Colonel Train. How much of what happened today can I tell him? If the VC attack us tonight we might not be able to hold. But they won’t hit us now.”

“I guess he’d understand that, Steve. Wouldn’t look good for him to lose a camp. But he’s still not really an unconventional warfare man.”

Kornie nodded in dour agreement.

“Too bad he couldn’t spend a week with you,” I went on. “That would make a Sneaky Pete out of him if anything ever could.”

“He would court-martial me out of the Army after a week with me,” Kornie declared. I tended to agree.

The summer of 1968, the summer I turned into a soldier, was a good time for talking about war and peace. Eugene McCarthy was bringing quiet thought to the subject. He was winning votes in the primaries. College students were listening to him, and some of us tried to help out. Lyndon Johnson was almost forgotten, no longer forbidden or feared; Robert Kennedy was dead but not quite forgotten; Richard Nixon looked like a loser. With all the tragedy and change that summer, it was fine weather for discussion.

And, with all of this, there was an induction notice tucked into a corner of my billfold.

So with friends and acquaintances and townspeople, I spent the summer in Fred’s antiseptic cafe, drinking coffee and mapping out arguments on Fred’s napkins. Or I sat in Chic’s tavern, drinking beer with kids from the farms. I played some golf and tore up the pool table down at the bowling alley, keeping an eye open for likely-looking high school girls.

Late at night, the town deserted, two or three of us would drive a car around and around the town’s lake, talking about the war, very seriously, moving with care from one argument to the next, trying to make it a dialogue and not a debate. We covered all the big questions: justice, tyranny, self-determination, conscience and the state, God and war and love.

College friends came to visit: “Too bad, I hear you’re drafted. What will you do?”

I said I didn’t know, that I’d let time decide. Maybe something would change, maybe the war would end. Then we’d turn to discuss the matter, talking long, trying out the questions, sleeping late in the mornings.

The summer conversations, spiked with plenty of references to philosophers and academicians of war, were thoughtful and long and complex and careful. But, in the end, careful and precise argumentation hurt me. It was painful to tread deliberately over all the axioms and assumptions and corollaries when the people on the town’s draft board were calling me to duty, smiling so nicely.

“It won’t be bad at all,” they said. “Stop in and see us when it’s over.”

So to bring the conversations to a focus and also to try out in real words my secret fears, I argued for running away.

I was persuaded then, and I remain persuaded now, that the war was wrong. And since it was wrong and since people were dying as a result of it, it was evil. Doubts, of course, hedged all this: I had neither the expertise nor the wisdom to synthesize answers; most of the facts were clouded, and there was no certainty as to the kind of government that would follow a North Vietnamese victory or, for that matter, an American victory, and the specifics of the conflict were hidden away—partly in men’s minds, partly in the archives of government, and partly in buried, irretrievable history. The war, I thought, was wrongly conceived and poorly justified. But perhaps I was mistaken, and who really knew, anyway?

Piled on top of this was the town, my family, my teachers, a whole history of the prairie. Like magnets, these things pulled in one direction or the other, almost physical forces weighting the problem, so that, in the end, it was less reason and more gravity that was the final influence.

My family was careful that summer. The decision was mine and it was not talked about. The town lay there, spread out in the corn and watching me, the mouths of old women and Country Club men poised in a kind of eternal readiness to find fault. It was not a town, not a Minneapolis or New York, where the son of a father can sometimes escape scrutiny. More, I owed the prairie something. For twenty-one years I’d lived under its laws, accepted its education, eaten its food, wasted and guzzled its water, slept well at night, driven across its highways, dirtied and breathed its air, wallowed in its luxuries. I’d played on its Little League teams. I remembered Plato’s Crito, when Socrates, facing certain death—execution, not war—had the chance to escape. But he reminded himself that he had seventy years in which he could have left the country, if he were not satisfied or felt the agreements he’d made with it were unfair. He had not chosen Sparta or Crete. And, I reminded myself, I hadn’t thought much about Canada until that summer.

The summer passed this way. Gold afternoons on the golf course, a comforting feeling that the matter of war would never touch me, nights in the pool hall or drug store, talking with towns-folk, turning the questions over and over, being a philosopher.

Near the end of that summer the time came to go to the war. The family indulged in a cautious sort of Last Supper together, and afterward my father, who is brave, said it was time to report at the bus depot. I moped down to my bedroom and looked the place over, feeling quite stupid, thinking that my mother would come in there in a day or two and probably cry a little. I trudged back up to the kitchen and put my satchel down. Everyone gathered around, saying so long and good health and write and let us know if you want anything. My father took up the induction papers, checking on times and dates and all the last-minute things, and when I pecked my mother’s face and grabbed the satchel for comfort, he told me to put it down, that I wasn’t supposed to report until tomorrow.

After laughing about the mistake, after a flush of red color and a flood of ribbing and a wave of relief had come and gone, I took a long drive around the lake, looking again at the place. Sunset Park, with its picnic table and little beach and a brown wood shelter and some families swimming. The Crippled Children’s School. Slater Park, more kids. A long string of split-level houses, painted every color.

The war and my person seemed like twins as I went around the town’s lake. Twins grafted together and forever together, as if a separation would kill them both.

The thought made me angry.

In the basement of my house I found some scraps of cardboard and paper. With devilish flair, I printed obscene words on them, declaring my intention to have no part of Vietnam. With delightful viciousness, a secret will, I declared the war evil, the draft board evil, the town evil in its lethargic acceptance of it all. For many minutes, making up the signs, making up my mind, I was outside the town, I was outside the law, all my old ties to my loves and family broken by the old crayon in my hand. I imagined strutting up and down the sidewalks outside the depot, the bus waiting and the driver blaring his horn, the Daily Globe photographer trying to push me into line with the other draftees, the frantic telephone calls, my head buzzing at the deed.

On the cardboard, my strokes of bright red were big and ferocious looking. The language was clear and certain and burned with a hard, defiant, criminal, blasphemous sound. I tried reading it aloud.

Later in the evening I tore the signs to pieces and put the shreds in the garbage can outside, clanging the gray cover down and trapping the messages inside. I went back into the basement. I slipped the crayons into their box, the same stubs of color I’d used a long time before to chalk in reds and greens on Roy Rogers’ cowboy boots.

I’d never been a demonstrator, except in the loose sense. True, I’d taken a stand in the school newspaper on the war, trying to show why it seemed wrong. But, mostly, I’d just listened.

“No war is worth losing your life for,” a college acquaintance used to argue. “The issue isn’t a moral one. It’s a matter of efficiency: what’s the most efficient way to stay alive when your nation is at war? That’s the issue.”

But others argued that no war is worth losing your country for, and when asked about the case when a country fights a wrong war, those people just shrugged.

Most of my college friends found easy paths away from the problem, all to their credit. Deferments for this and that. Letters from doctors or chaplains. It was hard to find people who had to think much about the problem. Counsel came from two main quarters, pacifists and veterans of foreign wars.

But neither camp had much to offer. It wasn’t a matter of peace, as the pacifists argued, but rather a matter of when and when not to join others in making war. And it wasn’t a matter of listening to an ex-lieutenant colonel talk about serving in a right war, when the question was whether to serve in what seemed a wrong one.

On August 13, I went to the bus depot. A Worthington Daily Globe photographer took my picture standing by a rail fence with four other draftees.

Then the bus took us through corn fields, to little towns along the way—Lismore and Rushmore and Adrian—where other recruits came aboard. With some of the tough guys drinking beer and howling in the back seats, brandishing their empty cans and calling one another “scum” and “trainee” and “GI Joe,” with all this noise and hearty farewelling, we went to Sioux Falls. We spent the night in a YMCA. I went out alone for a beer, drank it in a corner booth, then I bought a book and read it in my room.

By noon the next day our hands were in the air, even the tough guys. We recited the proper words, some of us loudly and daringly and others in bewilderment. It was a brightly lighted room, wood paneled. A flag gave the place the right colors, there was some smoke in the air. We said the words, and we were soldiers.

I’d never been much of a fighter. I was afraid of bullies. Their ripe muscles made me angry: a frustrated anger. Still, I deferred to no one. Positively lorded myself over inferiors. And on top of that was the matter of conscience and conviction, uncertain and surface-deep but pure nonetheless: I was a confirmed liberal, not a pacifist; but I would have cast my ballot to end the Vietnam war immediately, I would have voted for Eugene McCarthy, hoping he would make peace. I was not soldier material, that was certain.

But I submitted. All the personal history, all the midnight conversations and books and beliefs and learning, were crumpled by abstention, extinguished by forfeiture, for lack of oxygen, by a sort of sleepwalking default. It was no decision, no chain of ideas or reasons, that steered me into the war.

It was an intellectual and physical stand-off, and I did not have the energy to see it to an end. I did not want to be a soldier, not even an observer to war. But neither did I want to upset a peculiar balance between the order I knew, the people I knew, and my own private world. It was not that I valued that order. But I feared its opposite, inevitable chaos, censure, embarrassment, the end of everything that had happened in my life, the end of it all.

And the stand-off is still there. I would wish this book could take the form of a plea for everlasting peace, a plea from one who knows, from one who’s been there and come back, an old soldier looking back at a dying war.

That would be good. It would be fine to integrate it all to persuade my younger brother and perhaps some others to say no to wars and other battles.

Or it would be fine to confirm the odd beliefs about war: it’s horrible, but it’s a crucible of men and events and, in the end, it makes more of a man out of you.

But, still, none of these notions seems right. Men are killed, dead human beings are heavy and awkward to carry, things smell different in Vietnam, soldiers are afraid and often brave, drill sergeants are boors, some men think the war is proper and just and others don’t and most don’t care. Is that the stuff for a morality lesson, even for a theme?

Do dreams offer lessons? Do nightmares have themes, do we awaken and analyze them and live our lives and advise others as a result? Can the foot soldier teach anything important about war, merely for having been there? I think not. He can tell war stories.

Even before arriving at Chu Lai’s Combat Center on June 3, 1968, Private First Class Paul Berlin had been assigned by MACV Computer Services, Cam Ranh Bay, to the single largest unit in Vietnam, the Americal Division, whose area of operations, I Corps, constituted the largest and most diverse sector in the war zone. He was lost. He had never heard of I Corps, or the Americal, or Chu Lai. He did not know what a Combat Center was.

It was there by the sea.

A staging area, he decided. A place to get acquainted. Rows of tin huts stood neatly in the sand, connected by metal walk-ways, surrounded on three sides by wire, guarded at the rear by the sea.

A Vietnamese barber cut his hair.

A bored master sergeant delivered a Re-Up speech.

A staff sergeant led him to a giant field tent for chow, then another staff sergeant led him to a hootch containing eighty bunks and eighty lockers. The bunks and lockers were numbered.

“Don’t leave here,” said the staff sergeant, “unless it’s to use the piss-tube.”

Paul Berlin nodded, afraid to ask what a piss-tube was.

In the morning the fifty new men were marched to a wooden set of bleachers facing the sea. A small, sad-faced corporal in a black cadre helmet waited until they settled down, looking at the recruits as if searching for a lost friend in a crowd. Then the corporal sat down in the sand. He turned away and gazed out to sea. He did not speak. Time passed slowly, ten minutes, twenty, but still the sad-faced corporal did not turn or nod or speak. He simply gazed out at the blue sea. Everything was clean. The sea was clean, the sand was clean, the air was warm and pure and clean. The wind was clean.

They sat in the bleachers for a full hour.

Then at last the corporal sighed and stood up. He checked his wristwatch. Again he searched the rows of new faces.

“All right,” he said softly. “That completes your first lecture on how to survive this shit. I hope you paid attention.”

During the days they simulated search-and-destroy missions in a friendly little village just outside the Combat Center. The villagers played along. Always smiling, always indulgent, they let themselves be captured and frisked and interrogated.

PFC Paul Berlin, who wanted to live, took the exercise seriously.

“You VC?” he demanded of a little girl with braids. “You dirty VC?”

The girl smiled. “Shit, man,” she said gently. “You shittin’ me?”

They pitched practice grenades made of green fiberglass. They were instructed in compass reading, survival methods, bivouac SOPs, the operation and maintenance of the standard weapons. Sitting in the bleachers by the sea, they were lectured on the known varieties of enemy land mines and booby traps. Then, one by one, they took turns making their way through a make-believe minefield.

“Boomo!” an NCO shouted at any misstep.

It was a peculiar drill. There were no physical objects to avoid, no obstacles on the obstacle course, no wires or prongs or covered pits to detect and then evade. Too lazy to rig up the training ordnance each morning, the supervising NCO simply hollered Boomo when the urge struck him.

Paul Berlin, feeling hurt at being told he was a dead man, complained that it was unfair.

But Paul Berlin stood firm. “Look,” he said. “Nothing. Just the sand. There’s nothing there at all.”

The NCO, a huge black man, stared hard at the beach. Then at Paul Berlin. He smiled. “ ’Course not, you dumb twirp. You just fucking exploded it.”

Paul Berlin was not a twirp. So it constantly amazed him, and left him feeling much abused, to hear such nonsense—twirp, creepo, butter-brain. It wasn’t right. He was a straightforward, honest, decent sort of guy. He was not dumb. He was not small or weak or ugly. True, the war scared him silly, but this was something he hoped to bring under control.

Late on the third night he wrote to his father, explaining that he’d arrived safely at a large base called Chu Lai, and that he was taking now-or-never training at a place called the Combat Center. If there was time, he wrote, it would be swell to get a letter telling something about how things went on the home front—a nice, unfrightened-sounding phrase, he thought. He also asked his father to look up Chu Lai in a world atlas. “Right now,” he wrote, “I’m a little lost.”

It lasted six days, which he marked off at sunset on a pocket calendar. Not short, he thought, but getting shorter.

He had his hair cut again. He drank Coke, watched the ocean, saw movies at night, learned the smells. The sand smelled of sour milk. The air, so clean near the water, smelled of mildew. He was scared, yes, and confused and lost, and he had no sense of what was expected of him or of what to expect from himself. He was aware of his body. Listening to the instructors talk about the war, he sometimes found himself gazing at his own wrists and legs. He tried not to think. He stayed apart from the other new guys. He ignored their jokes and chatter. He made no friends and learned no names. At night, the big hootch swelling with their sleeping, he closed his eyes and pretended it was not a war. He felt drugged. He plodded through the sand, listened while the NCOs talked about the AO: “Real bad shit,” said the youngest of them, a sallow kid without color in his eyes. “Real tough shit, real bad. I remember this guy Uhlander. Not such a bad dick, but he made the mistake of thinkin’ it wasn’t so bad. It’s bad. You know what bad is? Bad is evil. Bad is what happened to Uhlander. I don’t wanna scare the bejasus out of you—that’s not what I want—but, shit, you guys are gonna die.”