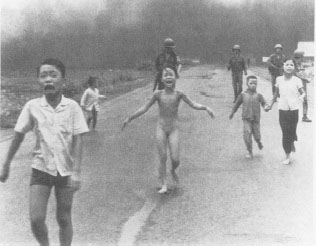

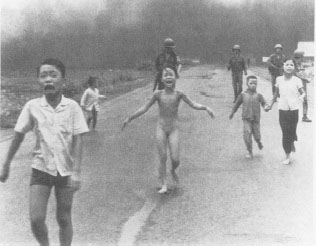

1972. A South Vietnamese girl flees a U.S. napalm strike by Highway 1.

During the early years of the Reagan administration, after the artistic success (and excess) of The Deer Hunter, Coming Home, and Apocalypse Now, Hollywood returned to form, giving America a more familiar, less complex vet, and by extension a simplified view of the war. The years between the two waves of major films were ruled first by Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo, the wronged vet on the rampage, and then by the emergence of a related subgenre, the prisoner-of-war adventure film. America, though ready to accept the warrior, still couldn’t look hard at the war. The one good serious film that came out during this period dealt with the fallout of the war in Cambodia, Roland Joffe’s The Killing Fields (1984), and it was British.

In the seventies, the psycho vet on a rampage was a staple of both film and TV, an emblem of America’s failure and a perfect catalyst for action. Typically, the vet was a damaged grunt or Green Beret or—more likely—a demolitions expert. In his bitterness against the government for wrongs real or imagined, the disturbed vet took hostages, went on a killing spree, or threatened to bomb public places until the law (our heroes) brought him to justice, often killing him. Rarely, as in the case of Billy Jack, was the vet fighting for an honorable cause. He was a menace, a reminder of how insane and out of control the country had been back in the sixties—in essence, a symptom of a larger sickness the country as a whole had now supposedly overcome.

Like his brothers the earlier psycho vets, in First Blood (1982, the year of the Wall) John Rambo comes to a quiet town, runs afoul of the law, declares war on the authorities, and ends up leveling the place with his specialized training. But unlike his predecessors, Rambo is the hero of the film. The town is corrupt, and in contrast to Billy Jack, Rambo’s noble cause is not universal brotherhood but merely the acknowledgment that the vet did his part and shouldn’t be ostracized for it. Paradoxically, Rambo the psycho vet is supposed to convince the audience of the average vet’s humanity and courage. Of course, the level of violence in the film contradicts this, but no matter, in the end we’re cheering. Interestingly, like Billy Jack, Rambo turns to both Native American and Far Eastern tactics to win his battle against the corrupt establishment; he becomes a lone guerrilla who’s one with the land, very much the frontier hero.

If First Blood could possibly be misconstrued as pro-vet, antigovernment and even antiwar, the second installment of the series, Rambo: First Blood, Part II (1985), could not. In the sequel Rambo returns to Vietnam to free American prisoners of war being held by both the Viet Cong and a few stray, sinister Russians. Though the mission is sabotaged by a dovish American politician, Rambo succeeds in an orgy of muscles and slow-motion firepower. The film’s politics are standard cold-war fare; the Vietnamese civilians are mere bystanders. Rambo—like the stereotypical vet of the period—is a victim who is now empowered to exact a personal revenge and in doing so achieves redemption. “What do you want?” he is asked at the end, and Rambo says, “For our country to love us as much as we love it.”

Later, in Rambo III, Stallone goes to Afghanistan to take on the whole Soviet Army. Like the other two movies, it’s a ridiculous shoot-’em-up with nothing to say, though all three made truckloads of money. The most interesting aspect of the series is surely the position of the vet as prototypical action hero—strong but misunderstood, brave and righteous, a true underdog. After years of fitting bombs together in seedy hotel rooms, the rampaging vet was suddenly someone to cheer.

Meanwhile in 1984, Chuck Norris, a B-movie version of Stallone (and formerly Bruce Lee’s sparring partner), launched the first installment of his POW-rescue series Missing in Action. Like Rambo, Norris’s character is a lone crusader for justice. He returns to Vietnam to find POWs he knows the VC are still holding—in fact are torturing with typical captivity narrative details. Stylized violence ensues. The movies are crude, even stupid, with the Vietnamese captors reminiscent of the evil Japanese guards in World War II films. They die by the bunch and the good guys ride away to big music.

The POW-rescue movies were huge successes as action flicks. While Uncommon Valor (1983) was both the first and the best of the lot, its star, Gene Hackman, didn’t have the drawing power of Norris or Stallone, and its producers didn’t feel it could benefit from a sequel. Still, as a group, the movies are interesting in their use of both the war and the vet. By framing the films (and the war) in terms of the documented Vietnamese mistreatment of POWs, the rescue movie gives American viewers a simplified moral high ground that was decidedly absent during the war. The vet finally gets his chance to reclaim America’s lost honor as well as the missing victory.

The Reagan eighties were a strikingly heroic time for the media-created figure of the Vietnam vet. After the dedication of the Wall and the oral history boom, Americans were eager to redress the past and canonize the vet as a forgotten hero. A sympathy that had been withheld for more than a decade burst forth in book after book. In each, the vet was portrayed as a noble victim, someone who’d given up his youth, his body, or his peace of mind for his country. While many of the books were well received—even lauded—by vets, Hollywood’s versions of the war were corny and cartoonish, an embarrassment. The real Vietnam was still missing.

Oliver Stone served in the Third Battalion of the Army’s 25th Infantry Division in 1967-68. After the war he became interested in film, eventually hooking up, like many young filmmakers, with Roger Corman’s production company in the late seventies. His earliest works as a screenwriter and director of B-pictures fit the Gorman formula—fast, violent, and sensational. His first mainstream scripts—for Alan Parker’s Midnight Express, Michael Cimino’s Year of the Dragon (widely picketed for its treatment of Asian-Americans), and Brian DePalma’s Scarface—seemed an extension of that sensibility. Only in Salvador (1986) did Stone begin to include the overt criticisms of the American political system that he’s become known for. That same year, he released what is commonly regarded as the best and most realistic film about the American war in Vietnam—Platoon.

The storyline of Platoon is standard fare. Like many of the oral histories, Platoon seems to follow the arc of the Bildungsroman. A quote from Ecclesiastes precedes the film—“Rejoice, O young man, in thy youth”—immediately followed by the perfectly green Chris Taylor (Charlie Sheen) arriving on an airport tarmac in Vietnam only to face a trolley of carts hauling body bags and a line of jive-talking short-timers, one with the thousand-yard stare. Like Willard in Apocalypse Now (played by Charlie’s father, Martin Sheen), Chris tells us his tale in a portentous voice-over, supposedly a letter or series of letters to his grandmother, though this device fades away later, when he tells the audience things his character would never tell his grandma.

We go out on patrol for the first time with Chris, and Stone pours on the realistic details for which the film is known: the jungle, the bugs, the equipment, the lingo, the heat. The focus, as in the oral histories and realistic novels, is on the grunt’s daily existence, the everyday life. Suddenly the other greenie who came on board with Chris is killed in an ambush, and quickly we meet the power structure of the platoon: Sgt. Barnes (Tom Berenger), a macho professional soldier whose face is grotesquely scarred; his counterpart Sgt. Elias (Willem Dafoe), who helps Chris lug his extra gear; and the useless ROTC lieutenant who wants to give the orders but doesn’t know what to do. No one mourns the dead new guy, they just look at him with disgust. “Man’d be alive if he had a few more days to learn something,” Barnes says, pointing up the Bildungsroman theme.

“I think I made a big mistake coming here,” Chris tells us.

We stand down, head back to the firebase, where Chris shares his personal history with his buddies. Stone’s screenplay touches on racial and social inequality here, as well as piling on more sharply drawn details. “You volunteered for this shit?” one guy asks. “You got to be rich in the first place to think like that.”

It seems the platoon is split into two groups, the heads and the juicers. Chris finds the heads getting stoned in a bunker (to the Jefferson Airplane’s totally overused “White Rabbit”), and Elias, bare-chested and in a hammock, beckons him. “First time?” Elias asks, and then gives him a true shotgun, blowing the smoke down a gun barrel. “Put your mouth on this,” Elias says, and Chris does. Cut to Kevin Dillon’s character, Bunny, sitting in front of a Confederate flag, swigging a beer and talking garbage with Junior and Rodriguez. Bunny tosses around ethnic slurs and seems stupid and out of touch. Back in the bunker, the heads are slow-dancing with each other.

The platoon goes out and finds a tunnel complex. A booby trap kills a man, and later, in the confusion, another member of the platoon, Manny, turns up missing. They find him dead and staked to a tree, tortured. Barnes is pissed and leads the platoon into the nearest village, where the troops unleash their frustration on civilians. Swept up in the hatred, Chris makes a one-legged man dance, firing at the ground. Right in front of him, Bunny kills a retarded boy with his rifle butt. “Holy shit,” he marvels, “you see that fucking head come apart?” This sobers Chris, and soon Elias shows up to put a stop to the slaughter, facing off with Barnes.

The LT comes up and says the captain wants the place torched, and so the village burns to Samuel Barber’s syrupy Adagio. Chris regains his humanity, stopping a gang rape, saying, “She’s a fucking human being, man!”

Back at base, Elias reports the incident, but though the captain says there’ll be a court-martial if there were any “illegal killings,” nothing immediate comes of it.

Chris and Elias talk that night. “There’s no right or wrong in them,” Elias says of the stars.

“Do you believe?” Chris asks him, about the American involvement.

“In ’65, yeah. Now, no. We’re going to lose this war. We’ve been kicking people’s asses so long, I figure it’s time we got ours kicked.”

Chris ruminates on the split in the platoon. “I can’t believe we’re fighting each other when we should be fighting them.”

Back in the jungle, the platoon runs into some serious VC. They’re in danger of being overrun when Elias volunteers to outflank the enemy. The LT botches his grid coordinates and short rounds fall all around them. They’ve got to pull back, get the hell out. But Elias is still out there. Barnes says he’ll go get him. Instead, when he finds him, Barnes levels his weapon and pumps some rounds into him.

Barnes runs into Chris, who asks him where Elias is. Barnes says he’s dead, and they hop into the Hueys and get out of there just as the VC come streaming out of the jungle, Elias a few steps ahead of them, bleeding, stumbling, raising his arms toward the departing lift-ships. He dies in slow motion with Barber’s Adagio going, his arms out, Christlike.

Chris knows Barnes killed him. “When you know, you know,” he explains.

Barnes hears his explanation down in the heads’ bunker and challenges Chris to do something about it. Barnes sneers at the joint they’re sharing. “You smoke this shit to escape from reality? Me, I don’t need this shit. I am reality.” Barnes taunts Chris until Chris attacks him, but Barnes is too strong. Barnes marks his cheek with a knife and walks off.

They’re about to be sent back into the jungle. “It felt like we were returning to the scene of the crime,” Chris says. Rumor is they’re going to see action. Big Harold (Forrest Whitaker) says, “Somewhere out there’s the beast, and he’s hungry tonight.” Getting ready, Bunny says of the village killings, “I don’t feel like we done something wrong, but sometimes I get this bad feeling,” then invokes the World War II hero Audie Murphy.

That night, they’re overrun by the VC, and Stone administers poetic justice, killing Bunny in an over-the-top scene. In the middle of the confusion, Barnes and Chris square off. Barnes is about to kill Chris (his face strikingly like Willard’s here) when an airstrike hits and we’re blinded by white light.

Chris wakes to a red deer. Barnes is trying to crawl away. “Get me a medic,” he says. “Go on, boy.” Then when he realizes that Chris means to kill him, Barnes chides him: “Do it.”

Chris does.

In the end, good wins out over evil. The stoner dudes live, and Barnes’s right-hand man O’Neill gets stuck with the crappy task of leading second platoon. As the medevac lifts off, taking Chris away, Rhah, one of the heads, bangs his chest and lifts his arms in triumph, an echo of Elias’s last gesture.

Chris flies off, profile framed in the door of the chopper (again the Adagio), the green mountains of Vietnam (the Philippines) sliding by behind him. “I think now, looking back,” he concludes, “we did not fight the enemy; we fought ourselves, and the enemy was in us. The war is over for me now, but it will always be there the rest of my days, as I’m sure Elias will be, fighting with Barnes for what Rhah called the possession of my soul. There are times since I’ve felt like a child born of those two fathers.” Lastly, Chris cites for all veterans “an obligation to build again, to teach to others what we know, and to try with what’s left of our lives to find a goodness and a meaning to this life.”

The film ends with a placard: “Dedicated to the men who fought and died in the Vietnam War.”

With that wrap-up of a speech, it seems Platoon can be read as a Bildungsroman, as Chris moves from innocence to experience and can make a meaningful lesson of his service that he can use and pass along to others. He’s no longer the young man in Ecclesiastes, and while there may be little reason to rejoice, he’s survived his trial. He’s learned.

Oliver Stone struggled for years to get the backing to make Platoon, so it would be wrong to call it an instant success, but upon release the film garnered solid box-office receipts and sterling reviews, becoming something of a phenomenon. It was talked about, lauded, debated. Time magazine dedicated seven pages to it. Most critics noted the level of detail as well as the response of many veterans, who thought it the first film that showed what Vietnam was really like. In 1986, Platoon was sold and accepted as realism, perhaps even history. Stone had done the impossible, critics said, and the academy agreed. Platoon won the Oscar for best picture, and Stone won for best director.

Now, a decade later, it’s hard not to see Platoon— despite its attention to concrete detail—as an allegory for American society during the war. Chris is given the choice of backing the heads (the antiwar counterculture) or the juicers (the establishment), which, in Stone’s view of America, is an easy choice. And the day-to-day moral dilemmas of the American soldier in Vietnam—the grunt’s inner life—aren’t gone into in any real depth, only sideswiped during big, melodramatic scenes, most of which are, and were at the time, familiar clichés in the literature. The first dead, the U.S. atrocity in the village, the incompetent ROTC LT, Bunny the psycho—all of these would have been old hat to anyone who’d read the novels or the oral histories. But astonishing as this may seem, in 1986, thirteen years after the last U.S. ground troops left Vietnam, the American moviegoer had never seen any of them.

The major films that preceded Platoon focused not on combat but the effect of the war on America—the war as a way of understanding America. Platoon does this as well, but merely as subtext. On the surface, it deals with combat and the tensions and camaraderie between soldiers, and though it awkwardly twists its plot and characters to set up almost cartoonish good-versus-evil climaxes, it succeeds around the edges, nails the atmosphere, takes us there. In a sense, all the smaller elements of the movie work, while the major pieces fail. What, finally, does Platoon tell us that we don’t already know? And yet, this is it, this is the Vietnam movie. It captured the attention of the nation as no other version of Vietnam has or possibly ever will.

There’s no certain answer as to why this happened. By 1986, as evidenced by the Rambo and Missing in Action films, America was ready to see the Vietnam vet as a hero, and this applied retroactively to the vet as soldier in Vietnam. Platoon gave America back the vet as innocent, the vet capable of seeing clearly and making the right choices. Chris Taylor (Christ?) is seen, as the eighties demanded, as a victim of the war, a survivor, and it’s his experience that’s held up as representative, not, as Chris implies at the end, a mix of Barnes’s and Elias’s. Chris isn’t a professional soldier or a frontier hero type; he’s an average middle-class kid, yet he volunteered, hoping “to see something I haven’t seen, learn something I don’t know yet.” It could be said that he’s an everyman, a regular guy yet not a reluctant draftee. There’s something of the adventurer in him, or the quest hero, which he fulfills by killing the clearly evil figure of Barnes. As in Apocalypse Now, the war itself is assumed to be absurd and unwinnable, but the inner struggle for the soul of America doesn’t end in an ambiguous tie, as it does with Willard slaying Kurtz and becoming one with the face of the stone Buddha, but in a clear victory for Good, with Chris surviving to bring his message home and teach it to others. For a supposedly gritty, realistic film about the American war in Vietnam, Platoon has the form of a melodrama and what could be seen—in a historical context—as an incredibly happy ending.

Just as The Deer Hunter beat Apocalypse Now into theaters, Platoon upstaged Stanley Kubrick’s long-awaited Full Metal Jacket (1987). Kubrick’s previous epics, such as Spartacus, Dr. Strangelove, A Clockwork Orange, and 2001, had established him as one of the finest filmmakers in the world, one with a keen—even cutting—political and cultural sensibility. When early word leaked that he was training his eye on Vietnam, critics wondered if he would be the one to finally “get the war right.” Kubrick had enlisted Gustav Hasford and Michael Herr to help him adapt Hasford’s The Short-Timers to the screen. The talent, it seemed, was in place, and hopes for the film were high; it had been seven years since Kubrick’s last release, The Shining, and that movie, though obviously brilliant in parts, had been widely met with disappointment. This would be Kubrick’s return to form. And so, like Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket steamed into theaters both too late and burdened with impossible critical expectations.

The movie opens with recruits being shorn of their locks to a country-western tune, “Good-bye My Darling, Hello Vietnam,” and soon it’s apparent that we’re going to spend a good deal of time (half the film, in fact) going through basic training with this group of Marines. In the barracks, drill instructor Gunny Hartman (Lee Ermey, a real-life DI before taking up acting) berates his charges in an extended and hilarious routine, giving our major players their new names—Joker (Matthew Modine), Cowboy (Arliss Howard), and Gomer Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio)—and laying out his philosophy of the Corps. His harangue is full of lines like, “Only steers and queers come from Texas. Do you suck dicks? You look like you could suck a golfball through a garden hose. You look like the kind of person who would fuck someone in the ass and not give him the courtesy of a reach-around.” He leads his men through PT (physical training), calling obscene cadences and intimidating the fat, hapless Pyle. He instructs the recruits to give their rifle a girl’s name and to sleep with it. “No more finger banging Mary Jane Rottencrotch,” this is the only pussy they’re going to get. In making these boys into men, Hartman stresses the immortality of the Corps, saying “God’s got a hard-on for Marines,” and in one brutal sequence, he strikes Joker for saying he doesn’t love the Virgin Mary. Impressed by Joker’s courage in standing up to him, Hartman makes him squad leader.

The training continues, as Joker narrates the change in the men in a flat voice-over. Pyle can’t hack it, and Hartman puts Joker in charge of shaping him up. It’s no use. Again and again, we see Pyle lagging behind the group, his trousers around his ankles and his thumb in his mouth. When he talks with Joker, it seems he’s reverting to childhood; he can’t button his shirt, he doesn’t know left from right. On the rifle range, Hartman tells them that a Marine needs a hard heart to kill, and later, after Pyle screws up and Hartman punishes the squad for it, Joker becomes at first a reluctant and then a vicious participant in a blanket party as the whole squad beats the sleeping Pyle. In the darkened barracks, Pyle cries like a baby, and Joker plugs his ears with his fingers.

Pyle degenerates further, developing a strange relationship with his rifle, Charlene. On the range, he finds the one thing he can master. Earlier, Hartman cited the marksmanship of Lee Harvey Oswald and Charles Whitman (the University of Texas tower sniper) as products of the Marine Corps. Cowboy and Joker are worried about Pyle, and the night after they graduate and receive their assignments, Joker finds him in the head with his rifle, obviously deranged. He calls for Hart-man, who comes in with his usual over-the-top bluster—“What is your major malfunction, numbnuts? Didn’t mummy and daddy show you enough attention when you were a child?”—and Pyle blows him away, then eats Charlene and splashes the back of his head all over the clean white tiles.

Cut to Saigon, awash in signage and blatting traffic. A whore cruises Joker, now a combat correspondent, and Rafterman (Kevyn Major-Howard), his green photographer, as Nancy Sinatra belts out “These Boots are Made for Walkin’.” “Me so horny,” the whore entices Joker, “Me love you long time.” A Saigon cowboy snatches Rafterman’s camera and jumps on a buddy’s Honda. Afterward, Rafterman gripes about the ingratitude of the Vietnamese. “It’s just business,” Joker says.

At a Stars and Stripes briefing in Da Nang, we see how Joker’s out-of-it editor only wants to publish good news, asking Joker to change his phrasing (“search and destroy” becomes “sweep and clear”) and even to fabricate stories (“grunts like reading about dead officers”). It’s Tet 1968, and that night in the barracks Rafterman and Joker are talking about “getting back into the shit” when the VC hit the front gate to the tune of “The Chapel of Love.” Our green heroes rush out to a bunker, Joker manning a machine gun. “I’m not ready for this shit,” he admits.

The next morning the wire is strung with dead VC. At his Stars and Stripes briefing, Joker mouths off, and his editor assigns him to cover the enemy occupation of Hue. (This is also the first time we see the peace sign on Joker’s helmet, as well as the motto: BORN TO KILL.) Rafterman asks if he can come along, and the two take a chopper north.

In Hue their first stop is a mass grave of civilians executed by either the VC or NVA, another learning experience for Joker. An officer comments on the contradictory messages on Joker’s helmet, asking if it’s a joke. Joker replies that he’s trying to say “something about the duality of man, sir.” The oblivious officer (as loopy as Kilgore in Apocalypse Now) tells him to jump on the wagon for the big win, and that “inside every gook there is an American trying to get out.”

Joker finds out that his old buddy Cowboy’s outfit is in Hue, and tracks him down. The two have a macho, insult-filled reunion, and Joker and Rafterman join Cowboy’s Lusthog Squad (with Animal Mother [Adam Baldwin], Eightball [Dorian Harewood], Crazy Earl, and T.H.E. Rock, among other colorful grunts) as they move through Hue. At one point, as in Apocalypse Now, a camera crew shoots them during combat. The men mug and wisecrack for the camera: “This is Vietnam—the movie.” “Is that you, John Wayne? Is this me?” “We’ll let the gooks play the Indians.”

A surprising amount of time is given to this kind of highly self-conscious criticism of, or simply statements about, the war. In the next sequence a squad member has been killed, and the survivors stand above him, all chipping in their thoughts; and immediately after this is a montage of mock TV interviews (a tactic familiar to viewers of the TV series M*A*S*H) in which the men comment on how little the Vietnamese appreciate their efforts, including the line “We’re shooting the wrong gooks.” As if to confirm this, in the next episode an ARVN soldier rides up on a Honda with a whore, whom he offers to the men, who are stretched out in an unbolted row of seats in front of a movie theater playing a Western.

Finally the squad moves out on patrol. Crazy Earl is killed by a sniper in a ruined building, leaving the untried Cowboy in charge, hunkered down behind a mound of rubble. Cowboy can’t seem to read the map. “What are we,” Joker asks, “lost?” Eightball tries to cross a patch of open ground to reach Crazy Earl and is gunned down—in slo-mo—by the sniper. Cowboy can’t control Animal Mother, who makes a heroic, John Wayne-like charge to safe cover. Animal Mother spots the sniper and covers the squad as they move up.

But there’s a line of fire through the building they’re crouched behind, and the sniper takes out Cowboy. He dies in Joker’s arms. It’s time for some payback.

The squad infiltrates the building, clears the first floor, moves upstairs. Joker is the first person to see the sniper, who wheels around to reveal she’s a woman, her braid flying, teeth gritted as she fires. Joker fumbles with his weapon, and is saved only because Rafterman unloads a clip into her. Shaken, Joker joins the circle of grunts standing over her. Rafterman is doing a little victory dance, humping the air. The sniper’s not dead, instead she’s croaking out a few words none of them understand. “She’s praying.” “No more boom-boom for this babysan,” Animal Mother says.

Joker’s worried. What should they do with her? “Fuck her. Let her rot.” “Cowboy’s wasted,” someone reminds him. Joker has to make a choice, and he chooses to kill her—out of mercy, it seems. “Fucking hardcore,” Animal Mother says, possibly misinterpreting his motives, and they move out.

It’s night and the fires are burning, the men spread out on patrol, stalking through the rubble. Joker’s voice-over says that though he’s “in a world of shit,” “I am not afraid.” As we close, the men are singing the theme from the Mickey Mouse Club. Fade out and the credits roll over the Stones’ “Paint It, Black.”

Initial reaction to Full Metal Jacket was cool. Critics called the film aimless, partitioned, episodic, and singled out Matthew Modine’s performance as wooden and ineffective. The screenplay was praised for its inventive use of language, but, film being a visual medium, the fact that Kubrick chose to shoot the movie in England rather than the Philippines (the location of choice) completely undermined Full Metal Jacket’s authenticity. In the wake of Platoon, the release of Full Metal Jacket couldn’t help but be anticlimactic. Comparisons with Stone’s film were inescapable and harsh, as were comparisons with Kubrick’s own earlier work. On the very basic level of cinematography, even The Shining was more interesting. Full Metal Jacket was a disappointment, the critics said, a failure on all counts.

That view of the film hasn’t changed. Veterans find the basic training section on target except for Pyle’s violence and the Vietnam sections unconvincing. Film critics continue to hold Full Metal Jacket up to Kubrick’s earlier work as well as to Platoon (more realistic) or Apocalypse Now (more daring and more interesting visually). Thematically though, the film—like most of Kubrick’s work—is chock-full of interesting stuff.

First, the film comments sharply on the Vietnam narrative as Bildungsroman. Where Platoon affirms the old and romantic idea of war as a crucible that builds men, Kubrick seems to be saying-through Pyle and then Joker and the men of the Lusthog squad—that Vietnam, or simply war, takes these boys not from innocence to experience but to numbness or madness. The ironic use of the Mickey Mouse theme song to close the film is a far cry from Chris Taylor’s heroic speechmaking.

Second, throughout the film Kubrick is examining the construction of gender and the institutionalized twining of sex and violence. The extremes to which the recruits have to create a dominant masculine self (violent, sexually potent) at the expense of anything feminine (weak, rotten, helpless) is shockingly reversed in the end, with the revelation that the sniper is a woman, is in fact what Gunny Hartman said they would have to become—a hardhearted killer of many enemies whose weapon is an expression of her will. And yet even then the men (except for Joker, our hero) persist in equating death with sexual domination, standing over her like participants in a gang rape, Rafterman dancing lewdly.

Third—and part of the construction of gender falls under this—in Full Metal Jacket, as in A Clockwork Orange and 2001, Kubrick is interested in the institutional and societal shaping or destruction of personality and the mystery of the human capacity for evil, this time playing it off American claims of innocence.

Beyond these conscious, well-developed themes, Full Metal Jacket looks at truth versus fiction in the media (especially in the official misuse of language), America as an inherently violent culture, war as business, race relations, and the institution as religion (and vice versa). Critics likewise have investigated Kubrick’s ironic use of pop culture and language, the film’s view of the Vietnamese, and Kubrick’s implementation of Herr’s dictum of the beauty or allure of destruction, the spectacle of war (you want to look and you don’t want to look).

An insatiable reader and writer, Kubrick fits his movies together like novels. As a literary object—a thing to be read—Full Metal Jacket continues to interest academics if not Vietnam vets, general moviegoers, or video renters. The film won’t go away, though, as Kubrick’s position as an intellectual moviemaker is firmly established, whereas Stone’s, like Cimino’s, seems to fade with each new release.

The second wave of films includes one other major work of note, John Irvin’s Hamburger Hill (1987), from a script by veteran James Carabatsos. The movie is remarkable solely for the fact that some vets rank it with or even above Platoon in its depiction of combat. While the script is leaden and obvious and the performances weak, the production crew’s attention to detail is sometimes impressive. On the whole, the film has little to say, since the action is given almost no context, political or otherwise, and the occasional statement about the war, the media, or America is inevitably old hat—as are, in fact, the details of Hamburger Hill. As with Platoon, the idea that a movie might get something right about Vietnam—if only the basest physical elements—was impressive to moviegoers (and vets) as late as 1987. As a study of character and war, however, Hamburger Hill owes more to the melting-pot platoon movies of World War II than to Vietnam.

Barry Levinson’s Good Morning, Vietnam (1987) did impressively at the box office, but other than Robin Williams’s typical shtick, the film gives us nothing that hasn’t already been done—and done better—elsewhere. Its widespread acceptance as a commercial vehicle is a good indicator of Hollywood suddenly embracing Vietnam if not as subject matter then at least as a palatable background.

The great success of the second wave was due almost entirely to Platoon, and for the first time, television sought to cash in on that success. In 1987, CBS developed a weekly series called Tour of Duty, in which the viewing audience followed the fortunes of a platoon in the Americal Division. Much of the writing was done by veterans, and the young actors involved underwent a less rigorous form of basic training so the details would be right. Though it earned solid reviews, the show lasted only two seasons.

More successful was ABC’s 1988 China Beach, which introduced us to a group of nurses stationed by the seaside R&R site. The writing and the performances were better than average for TV, and the details, especially in the first year, were handled carefully. Later the show slid into melodrama (some critics have dismissively called it a high-tone soap opera), and with the same anachronistic hindsight used by M*A*S*H in its later years contemporary issues such as nurses’ PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) were sensitively addressed in the context of the late sixties. Despite—or because of—its obvious debts to M*A*S*H, China Beach gobbled up solid ratings, established a following, and took home a number of Emmys before being canceled in 1992. For several years it was the only view of Vietnam offered to the average American viewer, and, like M*A*S*H and Korea, is probably at this writing—for those too young to remember the nightly newscasts—the most familiar face of the Vietnam War next to that of the hapless Forrest Gump (1994).

Since the second wave, a number of major Vietnam films have been released, including Brian De Palma’s Casualties of War (1989, from a script by vet David Rabe) and the two remaining entries in Oliver Stone’s Vietnam trilogy—his adaptations of Ron Kovic’s Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and Le Ly Hayslip’s Heaven and Earth (1993). Some have done well—notably Born on the Fourth, because of Tom Cruise’s star power—but no Vietnam film has captured the American imagination since Platoon, and it’s likely none will, at least for a while. The latest success was Disney’s Operation Dumbo Drop (1995), a comedy about a group of misfit, good-at-heart GI’s who have to deliver an elephant to a village. Since the second wave, there’s been an industry trend of using Vietnam simply as a backdrop for a standard genre film (detective, comedy) or to examine something else—say, women’s rights in China Beach, or the African American experience in The Walking Dead (1995)—not why America was there, what it was doing, and who paid the price. The prospect of a serious new Vietnam film, in 1998, seems remote. The common wisdom now in Hollywood is that Vietnam has been done and is therefore over with. But, like America’s view of the war, that will certainly change.