Chapter 1

Chapter 1

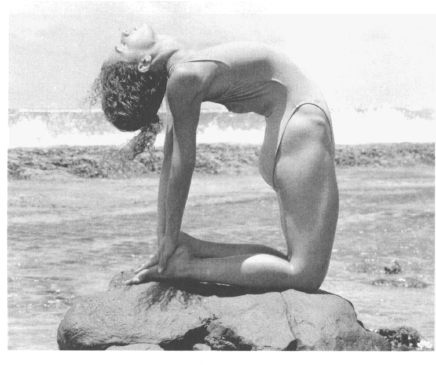

The Sanskrit word āsana derives from the verbal root as, meaning “to sit” or “to be present,” and, in the context of the Yoga tradition, means “to be established in a particular posture.” Historically the term refers to a wide range of bodily postures that have been transmitted by teachers in India for thousands of years. Because the forms of many of these postures have been more or less precisely defined in the classic texts of the Hatha Yoga tradition, each āsana is characterized by certain objective criteria; and, in fact, one traditional definition of āsana is “the arrangement of the different components of the body in a specific way.” However, the history of āsana is not a record of the possibilities of bodily contortion, nor simply a record of an ancient form of physical culture; rather, āsana evolved as an integral part of a comprehensive spiritual practice oriented toward purification, accomplishment, and realization.

Whether or not we are on the path to achieving our highest spiritual potential, āsana practice, in and of itself, promotes structural stability, physiological immunity, and emotional health. If we have the good fortune to begin āsana practice when we are young, it will help our bodies develop in a balanced way; or if we come to it as adults, it will help us restore and maintain balance as we grow older. Structurally, proper practice will promote stability, strength, flexibility, skeletal alignment, and mechanical freedom. Physiologically, proper practice will balance neurological and hormonal activity, strengthen cardiovascular and respiratory functioning, improve absorption of nutrients and elimination of wastes, and strengthen the body’s ability to resist and even overcome chronic disease. Emotionally, proper practice will increase our self-confidence, our tolerance for those different than us, our compassion for the suffering of ourselves and others, our capacity to withstand change, and our appreciation for the gift of life.

The essential qualities of āsana practice are given to us by Patañjali, the ancient authority on Yoga, in his Yoga Sūtras. These qualities are the following:

| Sthira: | to be conscious, alert, present, firm, stable |

| Sukha: | to be relaxed, comfortable, at ease, without pain or agitation |

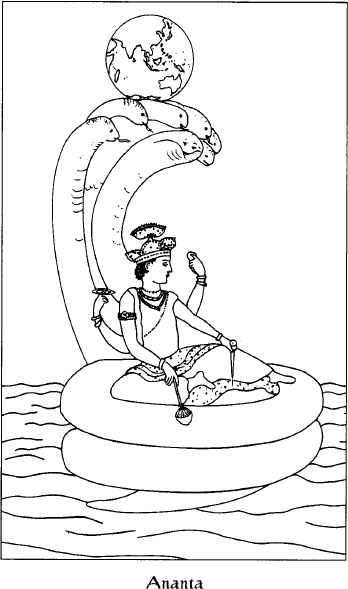

Sthira and Sukha are symbolized by the ancient Hindu story of Ananta, the Ādi Śesa, king of the Nāgas, who carries the world on his head and the Lord on his lap; and it is these qualities along with certain organizational principles and objective criteria that give us the guidelines to develop a safe and effective practice. According to this authoritative text, our ability to be present and aware in an āsana is through the breath. It is through the breath that we can truly link the mind to the body, not at an imaginary level but as an actual and tangible experience.

On a practical level, Ananta symbolizes the goal of our practice: the ability to take full responsibility for being a healthy human being in the context of our personal, social, and physical environment while at the same time being relaxed and at peace in our body, mind, and heart. Our āsana practice should be as if we are becoming Ananta: doing our work with full attention while at the same time providing a comfortable resting place for God in our hearts.

Though we all have the same basic structural and organic parts, we are nonetheless unique in our structural, physiological, and emotional functioning; and though we all have certain deep constitutional tendencies that remain constant, our own condition changes from day to day. Thus the key to the art of personal practice lies in learning how to accurately assess our present condition, how to set appropriate goals, and how to develop an appropriate practice.

Learning to accurately assess our present condition involves looking at what is really happening in our body as we practice. For example, we may accomplish the form of a posture beautifully and still actually miss the potential benefits or even neglect to see the potential harm of that posture! This may happen for two reasons: We may fail to recognize our own release valves; and/or we may be so focused on the form of a posture that we fail to consider its function, i.e., we fail to ask what we are really trying to accomplish by using it.

Release valves are compensatory mechanisms that occur when we are unable to stabilize a part of the body because of excessive mobility or restriction, habitual movement patterns, or lack of understanding and/or attention. There are many possible release valves in any posture; and because our ability to observe, identify, and block our own release valves is so fundamental to achieving the benefits of āsana practice, a full presentation of them appears in the chapters ahead.

The form-function problem, on the other hand, concerns the relationship between the classical form of a posture and its actual functional value. While it is true that the forms of the classical postures reveal a systematic record of the structural potential of the human body, achieving one of these forms does not necessarily indicate that we have achieved its function. The true value of these postures lies in their functional benefit to our own body, not in the objective character of their classical forms. Therefore, rather than focusing on the achievement of objective standards, we should focus on what is actually happening in our body as we practice. The classical postures should be used initially as mirrors to help us discover something about that actual condition. Then the information gained from this observation should be used to help us determine the direction of our practice.

Setting appropriate goals for our practice involves the ability to recognize change. Because our condition is always changing, we must continually redefine and renew our practice. With this in mind, we will explore throughout this book a broad spectrum of possible goals, including relieving chronic aches and pains, balancing conditions of excess or deficiency, promoting emotional health, and developing the body through challenging postures.

Because the spine is the structural core of the body, developing an appropriate āsana practice necessarily involves studying the structural relations between the various parts of the spine, analyzing the specific movements of āsana practice in relation to their effect on the spine, and developing movement patterns that bring all of the parts into proper relationship. In the chapters immediately ahead, we will explore the principles for planning an appropriate practice, including the role of the breath, the principles of adaptation, the science of sequencing, and the principles of movement.

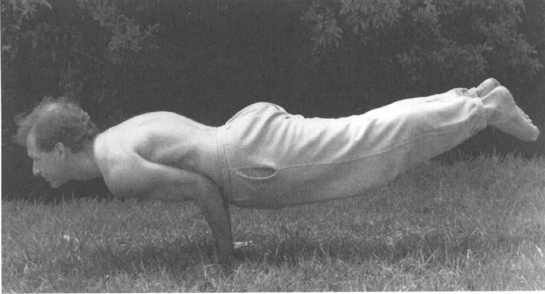

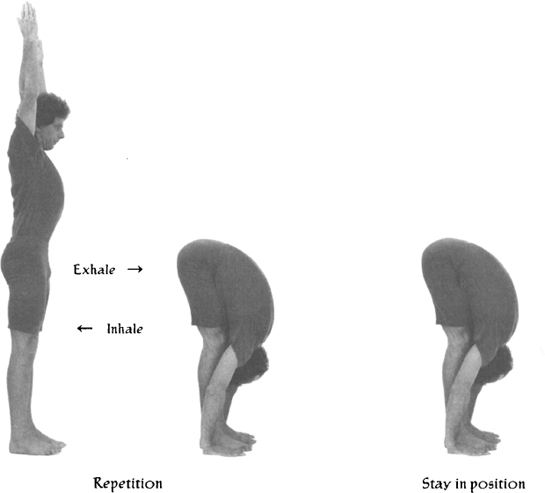

When the information gained in the process of self-observation—using the classical postures as mirrors to discover our actual condition—is combined with the principles mentioned above, we can adapt an āsana practice that truly respects our changing condition and our changing goals. Such a practice will include both the repetitive movements of the body into and out of particular postures, and the holding of particular postures for extended periods of time. Through alternate stretching and contracting, repetition increases circulation to the larger superficial skeletal muscles, making them stronger and more flexible. Thus repetition prepares us for holding postures for extended periods of time with minimal resistance. Through conscious movement with attention to our release valves, repetition helps us to identify habitual movement patterns and to develop new ones that are adapted to the structural and functional needs of our body. Thus repetition transforms the way we use our body in normal daily activity. In fact, according to the Viniyoga tradition, the most significant musculoskeletal and neuromuscular transformation occurs through this repetitive movement.

On the other hand, the most significant inner purification and physiological transformation occurs through holding postures for an extended period of time. Through the application of specific deep breathing techniques while holding a relatively fixed posture, subtle but powerful internal movements are created that activate the deepest layers of the spinal musculature. These movements act as “prāna pumps,” which increase circulation to specific areas of the body, providing great benefit to the spine, organs, and glands.

Unless the body is sufficiently prepared, however, holding certain postures will be either impossible or useless. For example, tight joints, a big belly, or a muscle-bound body may inhibit one’s ability to even get into certain postures or, once in them, create too much tension for one to realize the postures’ benefits. On the other hand, while hypermobility of the joints may make it easy to get into certain postures, they may still be without benefit. In the first case, the use of repetition is called for to help the body develop in the direction of the particular postures. In the second case, the use of adaptation is called for to help block the release valves so that the benefits of the postures may be achieved.

Considering this, a question emerges: How do we use āsanas in such a way that the movements promote new and more useful possibilities for our body, rather than increasing stress and tension or simply re-enforcing existing conditions? The answer: By bringing our full attention to the integrated relationship between the breath, movement, and the spine. By linking our awareness to the spine through our breath, instead of focusing on the external form of a posture, we are able to feel from the inside how our body is responding to the movement. Once this awareness has been established, then we can proceed to find the most effective combination of repetition and hold, of adaption of form and use of breath, and of sequencing, without losing touch with the essential purpose of Yoga practice.

In this way, āsana practice becomes an experimental ground in which we experience, learn, and grow. With this kind of an open attitude of investigation and discovery, our practice will stay alive and fresh. In a gradual and progressive way our body will be transformed toward greater balance, strength, and flexibility; and the result will be a deep and effective āsana practice, regardless of the mechanical possibilities of our body.

The six vital functions—the life breath, the faculty of speech, the eye, the ear, the mind, and the semen—were disputing among themselves about which was most excellent. They brought their dispute to Brahma, who told them, “One of you is most excellent after whose departure the body is thought to be worse off.”

The organ of speech departed and, having remained absent for a year, came back and said, “How have you been able to live without me?” They said, “As the dumb, not speaking with speech but breathing with the breath, seeing with the eye, hearing with the ear, knowing with the mind, procreating with the semen. Thus we have lived.”

The eye departed and, having remained absent for a year, came back and said, “How have you been able to live without me?” They said, “As the blind, not seeing with the eye, but breathing with the breath, speaking with the speech, hearing with the ear, knowing with the mind, procreating with the semen. Thus we have lived.”

The ear departed and, having remained absent for a year, came back and said, “How have you been able to live without me?” They said, “As the deaf, not hearing with the ear, but breathing with the breath, speaking with the speech, seeing with the eye, knowing with the mind, procreating with the semen. Thus we have lived.”

The mind departed and, having remained absent for a year, came back and said, “How have you been able to live without me?” They said, “As the stupid, not knowing with the mind, but breathing with the breath, speaking with the speech, seeing with the eye, hearing with the ear, procreating with the semen. Thus we have lived.”

Then semen departed and, having remained absent for a year, came back and said, “How have you been able to live without me?” They said, “As the impotent, not procreating with the semen, but breathing with the breath, speaking with the speech, seeing with the eye, hearing with the ear, knowing with the mind. Thus we have lived.”

Then as the life breath was about to depart, even as a large and spirited horse might pull up the pegs to which his feet are tied, even so did it pull up those other vital functions together. They gathered around him and said, “Venerable Sir, do not depart, verily, we shall not be able to live without you. You are the most excellent among us.”

BRHAD-ĀRANYAKA UPANISAD VI, 1-13.

CHĀNDOGYA UPANISAD VI, 6-12.*

From ancient times, the breath has been recognized as the key to our life. In fact, in the root languages of modern cultures, the word for breath is also the word for spirit, life force, even God.

While normal unconscious breathing is controlled by the autonomic nervous system, the breath is readily accessible to conscious control and can therefore provide a link between our conscious mind and our anatomy, physiology, deeper emotional states, and our deepest spiritual potential. And it is this unique quality of the breath that qualifies it as the primary concern of the science of self-development that we find in the Yoga tradition. For the moment, we will specifically focus on the structural aspects of the breath as they relate to āsana practice, leaving the deeper aspects for a later consideration.

The particular techniques of breathing used in āsana practice are designed to maximize certain structural effects of inhale and exhale; and the postures themselves can be considered as a way to deepen or extend these structural effects of the breath. Moreover, all movement in āsana is initiated through the action of the breath and is guided by the breath. In other words: Breath is always initiated prior to movement; it evokes a natural movement of the spine, and the action of an āsana is coordinated with this movement. An analogy can be made to swimming in a river, the current of the river being the breath; and, while there are exceptions, the general rule of āsana practice is to first feel the current, and then swim with it.

Like all movement in the body, the mechanics of breathing are related to muscular contraction; and inhalation is specifically initiated as a result of the contraction of the intercostal muscles (the muscles between the ribs) and the diaphragm. This process is as follows: The intercostals contract; the rib cage elevates; the diaphragm contracts downward; the elevation of the rib cage, combined with the downward movement of the diaphragm, creates a negative density in the thoracic cavity, allowing air to be sucked into the lungs; and the result is an expansion of the thoracic cavity. Other muscles involved in the process include the erector spinae, the semispinalis, the multifidus, the serratus posterior group, and the interspinalis—all of which contribute to the elevation of the rib cage, expansion of the chest, flattening of the thoracic curve, and vertical extension of the spine.

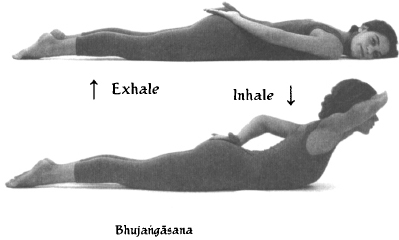

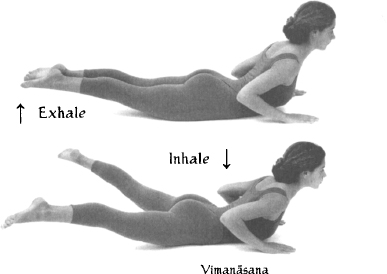

Conscious use of inhale in āsana practice should enhance this natural process, and all of the following movements, when linked to inhale, are designed for this purpose: raising the arms, expanding the chest, arching the back, moving into backward bends and extension postures, and straightening of the spine from a forward bend, a twist, or a lateral position.

The technique of inhalation is one of the most commonly confused issues in āsana practice because, although its basic mechanics are as described above, a number of variations can be introduced for the purpose of producing special effects; and these variations somewhat modify the effects of the breath itself. Such variations include emphasizing the expansion of the upper, middle, or lower rib cage; emphasizing the expansion of the abdomen; or emphasizing some combination of these events. However, according to the Viniyoga tradition, the general rule is to begin the inhale with the expansion of the upper chest. As the inhalation progresses, move the expansion down into the middle and, finally, into the lower portion of the rib cage. In the last part of the inhale, the abdominal contraction initiated on exhalation (see below) can be released, beginning from the top and then releasing progressively downward.

Where inhalation is a function of muscular contraction, the normal unconscious exhalation is the result of the relaxation of the muscles responsible for inhalation. This process is as follows: As the intercostal muscles relax, the rib cage returns from its elevated position; as the diaphragm relaxes, it raises up; and the result is the expulsion of air from the lungs.

Unlike inhalation, conscious use of exhalation in āsana practice does not follow this natural process. Instead, rather than simply relaxing the muscles contracted to create the inhalation, we intentionally contract the abdominal muscles progressively from the pubic bone to the navel. This contraction is initiated at the rectus abdominis, and then engages both the obliques and transverse abdominis. In certain circumstances, we may also intentionally contract the superficial and deep musculature of the perineal floor, including the anal sphincter, the urethral sphincter, the levator ani muscles, and the deep transverse perineus. This action stabilizes the pelvic-lumbar relationship, creates more structural stability, helps in the flattening of the lumbar lordosis, and, when there is contraction of all the muscles mentioned above, it also supports the organs of the pelvis and lower abdomen.

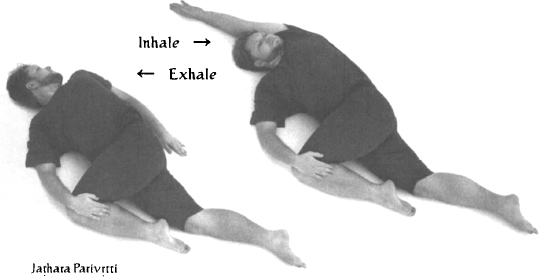

Movements linked to exhale are designed to increase this intentional effect, and they include lowering the arms; compression of the abdomen, which happens when moving into forward bends, twists, and lateral bends; and moving out of backward bends.

There is a paradox in the fact that as the structure moves upward on inhale, the attention should move downward, following the breath; and as the structure moves downward on exhale, the attention should move upward, following the breath. In other words: On inhale, the ribs are elevated and the spine extends upward, but the diaphragm and the attention move downward with the breath as it flows down into the lungs; and on exhale, the ribs drop downward, but the diaphragm and the attention moves upward with the breath as it flows up and out of the body.

In āsana practice, the main focus of attention should be on the movement of the spine through the breath. This is important because the mechanics of breathing help us to mobilize the spine in particular ways, and, at the same time, the conscious control of the breath enables us to link our attention directly to the movement of the spine. Because the spine is the core of all movement, linking our awareness to the spine brings a deeper level of awareness to all our movements. In short: instead of moving mechanically, we begin to move consciously.

In fact, throughout āsana practice, the mind should control the breath, staying aware of how the spine is moving through the breath and how we are allowing the breath to guide our movements. In this way our postures are developed from the inside out; and instead of focusing on the external form of the posture, we begin to feel from the inside how the body is responding to the movement that is taking place. In this way, instead of using the will to impose form onto our structure, as we follow the lead of the breath, we begin to discover how to adapt the form of a posture to fulfill its function.

Perhaps one of the most important reasons to adapt our practice is to keep it from becoming mechanical. Our bodies become habituated by any kind of repetitive activity to move in particular patterns, until we can successfully perform these patterns with little or no conscious attention. We are much more likely to give our full attention to something that is new. Therefore, changing the practice helps keep it alive, awakens new interest, keeps familiarity from leading to inattention, and helps us stay present throughout the process.

Another reason to adapt our practice is that our physical and mental condition is always changing: one morning we may wake up with a stiff neck and another with a pain in our lower back; one afternoon we may have low energy but want to go out for the evening; or after a celebration, we come home with an upset stomach. Therefore, by adapting the practice, we are able to work on specific conditions as they arise.

In addition to managing day-to-day changes, adaptation is essential when working with any long-term problematic condition. Accordingly, these principles of adaptation are the basis for Yoga therapy, and examples of their application for common aches and pains, chronic diseases, and emotional health can be found in the chapters ahead.

Beyond this therapeutic application, adaptation is the way to develop our potential and achieve something new through our practice. For example, if our hips are very tight, elevating our buttocks in a seated forward bend will facilitate the forward rotation of our pelvis and thus help us stretch our low back.

On the other hand, if our hips are very loose, elevating our heels in a seated forward bend will inhibit the forward rotation of our pelvis and thus help us stretch our low back.

We can also use adaptation to emphasize different aspects of the same posture. For example, in the case of Vīrabhadrāsana this symmetric adaptation emphasizes flattening the thoracic curve, while this asymmetric adaptation emphasizes stretching the psoas muscles.

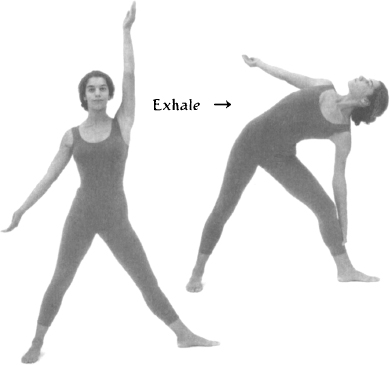

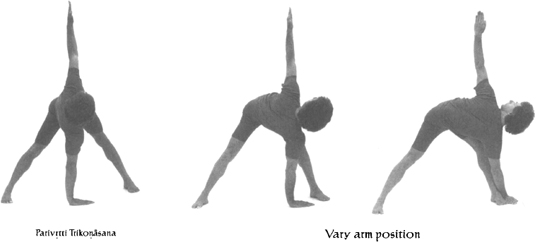

In Parivrtti Trikonāsana we can shift the location of spinal rotation by changing the placement of the hand on the floor. When the hand is midway between the feet, the primary rotation is in the mid-back; as the hand moves closer to the opposite foot, the primary rotation moves down the spine.

It is important to have a clear intention and orientation at the beginning of each practice. If we are clear, our practice will be efficient, effective, and safe; but if our intention is confused, we may actually end up doing harm to ourselves. For example, there is a tradition of sitting in the full lotus posture for prānāyāma (breathing) practices, and some schools suggest not practicing prānāyāma until this is possible for you. This is an unfortunate misrepresentation of the tradition, for although a well-conceived and adapted practice can help prepare the body for this posture, many people will never be able to sit in full lotus safely, and yet they would benefit greatly from prānāyāma. In fact, it is surprising how many Yoga teachers have had knee surgery because of inappropriate use of this posture. Therefore, the intention and orientation of our practice should be based on a realistic assessment of our needs, limitations, and potentials.

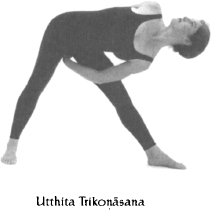

In most postures, use of the arms can be adapted to make the postures more or less challenging, and can even be used to shift the postures’ effects altogether. Look, for example, at these different possibilities:

One-arm variations lessen the work load, reduce stress in the neck and shoulders, and emphasize each side independently. Sweeping arm movements also lessen the workload and reduce stress in the neck and shoulders, and when used in combination with head movements, they also help to stretch and strengthen the neck and shoulders. Bending the arms reduces stress in the neck and shoulders, and bending and straightening the arms helps bring awareness to the thoracic curve and facilitates flattening it. Using the arms as levers increases the potential to work deeper into the posture, although there is also an increased risk to the joints. Also, as can be seen from these examples, the same type of arm adaptation can be applied in different types of movements. For example, when one-arm sweeping movements are used in combination with turning the head in a forward bend, a twist, or a backward bend, the benefit of this adaptation to the neck and shoulders is increased.

In most postures, the position of the legs can be adapted to make the postures more or less challenging, and can even be used to shift their effects altogether. Look, for example, at these different possibilities:

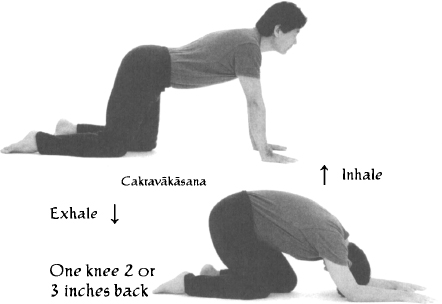

Bending the knees in standing postures lowers the center of gravity and facilitates the stretching of the low back. Bending the knees in seated postures can be used to either facilitate or inhibit the forward rotation of the pelvis, and often reduces stress in the low back. Increasing the distance between the feet in standing or seated postures increases and modifies the stretching of the legs. Widening the feet in the prone and supine postures above increases the contraction of the musculature of the hips. Displacing one knee backward increases the stretching of that side of the back. Rotating the knee externally, in the kneeling posture, increases the stretching of the inner thigh; and, in the supine twist, it increases the contraction of the musculature of the hip.

The place of origin determines the effect of a movement. For example: in a standing forward bend, originating the movement in the abdomen inhibits the forward rotation of the pelvis, while originating the movement in the hips facilitates it.

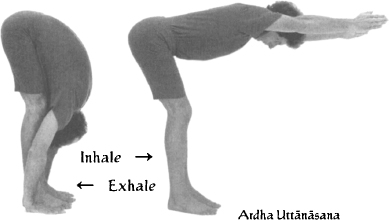

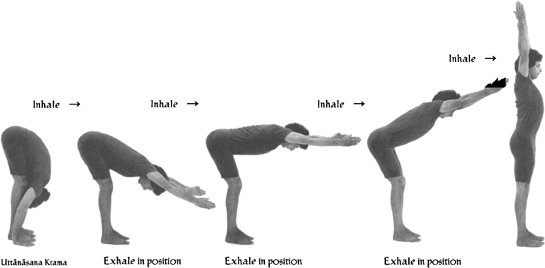

Moving into a posture in different ways also changes the effect of the posture. For example: coming up into Ardha Uttānāsana encourages the flattening of the upper back, and is most appropriate if you have a normal to excessive thoracic curve; while moving down into Ardha Uttānāsana encourages the rounding of the upper back, and is most appropriate if you have a normal to flattened thoracic curve.

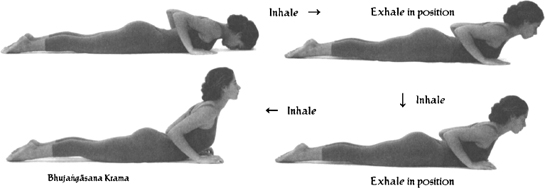

Another example is how to apply the force of the arms when coming up into Bhujangāsana: pushing down on the hands and lifting the chest deepens the arching effect in the lower back; while pulling back on the hands and pushing the chest forward deepens the arching effect in the upper back.

It is not correct to assume that the goal in any āsana is to move as far into the posture as possible; and sometimes the ability to move fully into a particular posture may even interfere with the ability to truly benefit from it. If you are one of those people who can easily drop into a posture like Upavistha Konāsana without any resistance, try bending one or both knees and keeping your sit bones on the floor as you bend forward. You will not go as far into the posture but will much more effectively stretch your low back.

Breaking a movement into stages can deepen its effect.

Speed of movement should always be coordinated with the length of a full breath. Speed influences the effect of movement: in general, faster movements being more energizing and slower movements more calming. However, if the movement is too quick it is easy to slip into unconscious movement patterns or to avoid sustained muscular work.

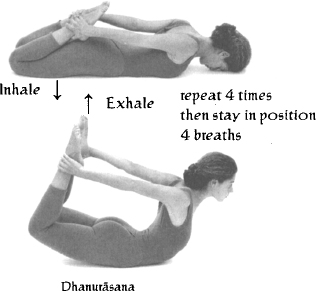

In general, we use the repetitive movement into and out of a posture as a preparation for staying in it. We can create various combinations of moving and staying to modify the effects of the positions.

This is done with postures that can be linked together easily to create a flowing sequence.

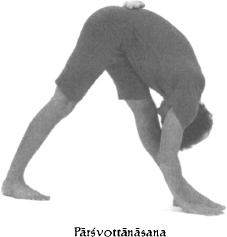

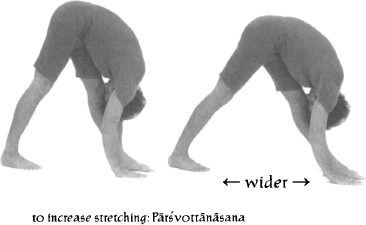

Generally, we suggest keeping attention on the breath and the parts of the body where the most action is occurring. However, shifting the focus of attention can also change the effect of a posture in surprising ways. For example, try moving into and out of Pārśvottānāsana four times on each side. On the first repetition, keep the attention on the back heel; on the second, keep the attention on the abdomen; on the third, keep the attention on the hands; and on the fourth, try to keep your attention on all three points at the same time. Notice how, each time, the effects of the movement shift.

At a different level, try placing your attention on a quality, such as kindness, and hold that in your thoughts. With this focus, you may notice that your practice softens and deepens.

Or, allow yourself to sincerely connect to the mysterious source of life itself, and hold that in your heart. With this focus, you may notice that your practice becomes a kind of prayer.

The breath can be adapted in a variety of ways to deepen the practice and produce different effects. Look, for example, at these different possibilities:

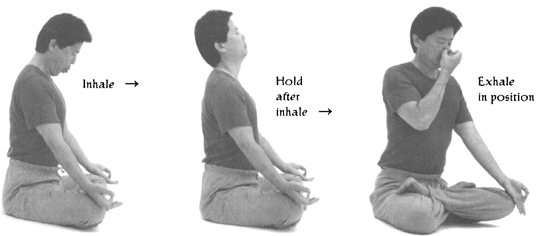

Holding after inhale generally extends the effects of the inhalation and is therefore usually applied in positions that emphasize inhalation. Holding after exhale generally extends the effects of exhalation and is therefore usually applied in positions that emphasize exhalation.

Or doing a movement while holding after exhale that is normally done on exhale.

Using vocal sound techniques in combination with postures effectively intensifies practice, focuses attention, deepens exhalation, increases circulation to the organs, and balances the emotions. Sound creates internal vibrations that increase circulation to different parts of the body.

The main factors that determine the effects of the sounds that are used are their particular vowels and consonants (varna), their pitch (svara), and their volume (bala). Though different traditions give different explanations about the use of the different vowel and consonant sounds, we can explore for ourselves how these various sounds resonate in our own bodies. There seems to be universal agreement that higher pitched sounds tend to resonate higher in the body and energize the system, while lower pitched sounds tend to resonate lower in the body and calm the system; and that louder sounds tend to awaken the energy and externalize the attention, while softer sounds tend to pacify the energy and internalize the attention.

Vocal sound techniques include humming, chanting simple syllables, chanting simple phrases that have certain meanings, and chanting more complete songs or prayers. Examples of the therapeutic uses of sound for common aches and pains, chronic diseases, and emotional health can be found in the chapters ahead.

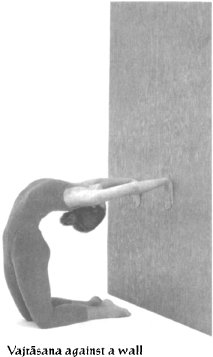

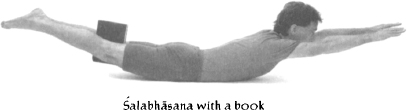

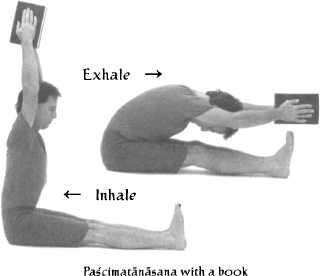

Props are useful when the capacity for movement is restricted due to structural limitations. They can be particularly useful in therapeutic application. They can also be useful to intensify work in a particular area. Props can include a wall, a table, a chair, blocks, cushions to support the body, straps for help with achieving closed-frame postures, and weights to intensify the effects of open-frame postures.

A well-conceived sequence is the key to an effective practice. Such a sequence has the qualities of order, harmony, and efficiency throughout, each posture and adaptation being selected and placed purposefully to create an integrated whole. Building effective sequences is at once an art and a science based on definite principles. So if you study and apply the principles detailed in this chapter, you will find your practices becoming progressively more elegant, refined, and relevant to your changing needs and interests, and in time, you will master the fine art of sequencing.

The many sequences appearing in this book are presented as models for approaching different specific conditions through practice. However, because no individual can be characterized by one specific condition alone, the sequences are necessarily descriptive rather than prescriptive, and each must be further adapted to respect your total situation, including your age, physical and emotional condition, profession, and personal interests. Therefore, the information in this chapter is also intended to help you in this process of adaptation.

Your Yoga practice should help to enhance the flow of your day; it should not be a predetermined and fixed affair that you fit in whenever you can. This means that the character of the sequences you use should change, depending upon the time of day, the activities that proceed practice, and the activities that follow it. For example, in the morning, you may want to do a more general warming up and energizing practice to prepare you for the day ahead. In the evening, on the other hand, you may want to do a more specific and relaxing practice to unwind from the stresses of the day. How you spend your day will also influence your practice. For example, if your work is physically demanding, you may want to use your practice to compensate for the physical stresses of your work and to help return balance to your body. If, on the other hand, your work is physically sedentary, you may want to use your practice to work out your body, to help release mental stress, and to achieve a clear mind.

The components of your practice are variable and can include any combination of the following elements: āsana, prānāyāma, chanting, meditation, prayer, and ritual. The keys to the science of combining these elements and arranging them in a particular order are the principles of Vinyāsa and Pratikriyā, which apply to all of the above-mentioned elements of a Yoga practice and to most activities in daily life as well.

Vinyāsa, literally “arranging” or “placing,” refers to the preparatory steps required to move the mind, breath, and/or body in a particular direction. The general idea of vinyāsa is to move progressively from the gross to the subtle, from the external to the internal, from the simple to the complex, and from the easy to the difficult. For example, āsana is more external than prānāyāma, and prānāyāma is more external than meditation. Therefore, you can use āsana to prepare the body and breath for prānāyāma, and prānāyāma to prepare the breath and mind for meditation.

In āsana practice, vinyāsa refers to the steps that must be taken in order to achieve a particular goal. Such goals might include achieving proficiency in a particular āsana, as demonstrated in the sequences in the chapters on āsana practice; working on a particular area of the structure, as demonstrated in the sequences in the chapters on common aches and pains; or producing an overall effect in the body, as demonstrated in the sequences in the chapters on chronic disease.

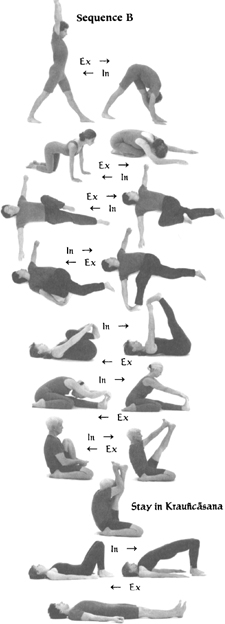

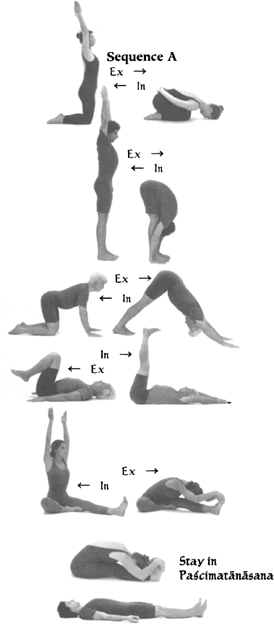

In preparing for a particular posture, it is helpful to progressively warm up the body by using simpler postures that move the body in the same direction. For example, simple forward bends can be used to prepare for deeper forward bends, simple back bends can be used to prepare for deeper back bends, et cetera. In making specific choices along these lines, characteristics of the main posture as well as specific body needs should also be considered. The sequences appearing on the following page are good examples for illustrating these principles. Both sequence A and sequence B are preparations for Krauñcāsana, using asymmetrical forward bends, in some cases with both hands holding the foot of the extended leg as in Krauñcāsana itself. Sequence A shows increased back bend preparation. If there is an exaggerated thoracic curve, this preparation will help in keeping the chest lifted while stretching the extended leg. Sequence B shows increased twisting preparation. If there is tightness in the low back and hips, this preparation will help in keeping the hips rotated forward while one leg is inwardly rotated and folded back.

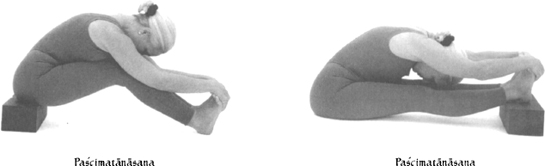

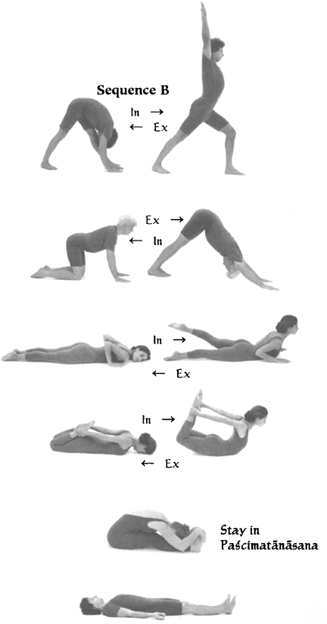

The effectiveness of any posture is influenced by the other postures it is combined with. If you look at the two sequences that appear below, you will notice examples of this interrelationship. Sequence A shows a general forward bending preparation for Paścimatānāsana. If there is tightness in the hips and/or low back, this preparation will help you to move further into the posture by progressively working to release the hips and stretch the low back. Sequence B, on the other hand, shows an unusual back bending preparation for Paścimatānāsana. If there is excessive looseness in the hips and/or loose low back, this preparation will help you experience the effects of the posture by progressively working to stabilize the hips and tighten the low back.

Pratikriyā, literally “counteracting,” refers to the compensatory steps required to return the mind, breath, and/or body to a neutral condition. The general idea of pratikriyā is that balance can be progressively restored by moving from the internal to the external, from the complex to the simple, and from the difficult to the easy. For example, simple prānāyāma can be used to reintegrate the body and the breath after a complex āsana practice; simple meditation can be used to reintegrate the breath and the mind after a deep prānāyāma practice; and simple āsana can be used to reintegrate the mind and the body after a long meditation.

In relation to āsana practice, pratikriyā specifically refers to the steps that can be taken to maintain or restore balance to the body. For example, such steps may be concerned with avoiding stress to a particular part of the body in the midst of a practice, or returning the body to a balanced and neutral condition at the end of a practice. Such appropriate compensation usually involves a simple posture or group of postures that will neutralize the stress accumulated from the preceding ones, and, accordingly, they relate to the specific areas of accumulated stress. For example, on different days you may need different counterposes to the same posture, depending on how your body is responding at the particular moment.

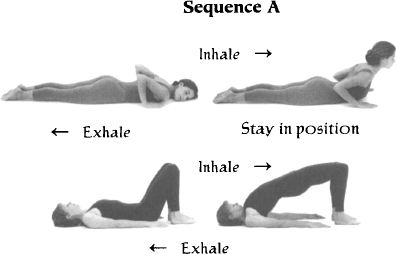

In sequence A below, the counterpose is for the neck and upper back. In sequence B the counterpose is for the lower back.

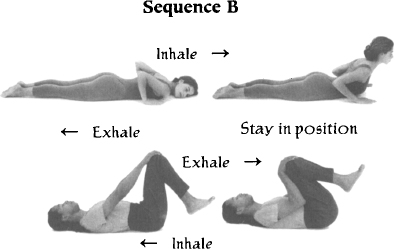

Often several postures will be required to return the body to a balanced and neutral condition. For example, after a deep back bend, you will need to balance the low back, hips, upper back, neck, and shoulders, and the order of these counterposes will depend on the needs of your own body. In sequence A on the next page, the priority is to the low back and hips. In sequence B, the priority is to the upper back, neck, and shoulders.

If your aim is to develop your body, challenging postures will be the major focus of your practice. You can begin with simpler movements, build progressively to more challenging postures, neutralize with simpler postures again, and end with a simple prānāyāma practice and rest.

If your aim is to develop your breath, prānāyāma will be the major focus of your practice. In this case, you can begin with some simple āsana practice to prepare the body and breath, then start the prānāyāma simply and move progressively into deeper and/or more complex techniques, neutralize with simpler breathing again, and end with a simple meditation and rest.

If your aim is to develop your mind, meditation will be the major focus of your practice. With this focus, you can begin with simple āsana, prānāyāma, and chanting to prepare the body, breath, and mind for the practice; then move into the meditation practice, and end with some simple āsana, to relieve any structural stress from extended sitting; and rest.

If your aim is to open your mind and heart to the sacred dimension of life, prayer and ritual will be the major focus of your practice. However, āsana, prānāyāma, chanting, and meditation can also be an integral part of your practice, helping to prepare for the pinnacle of the practice as well as to reintegrate to normal awareness after it is finished.

And if your aim is to do a therapeutic practice, any combination of the above elements may be appropriate, depending upon your condition.

1. Intention: Set an intention or goal for your practice. For example, your intention may be to achieve certain postures, to work a certain area or condition in your body, or to prepare for a prānāyāma and/or meditation practice.

2. Efficiency: Limit the number of postures and adaptations. Link your choices purposefully to the intention of your practice. A focused course can be more powerful, useful, and specific than a general one. In fact, too many postures can dilute the effect of the practice, just as eating too many foods at one meal can limit (overload) the body’s ability to absorb the nutrients.

3. Breath: Use the breath to link your attention to the spine and to move the spine. Maintain a deep and even breathing pattern throughout the practice. Use retention of the breath purposefully, and link it to the overall intention of the practice.

4. Transition: Take time to make the transition from other activities into your practice. Also within the practice, make transitions smooth. For example, use kneeling postures to transition from standing postures to postures on your back or stomach.

5. Cumulative stress: Use appropriate compensation for stresses that accumulate in the neck, shoulders, hips, and knees. For example, use arm movements to release stress accumulated in the shoulders from postures where the arms are fixed.

6. Risk: Postures that are risky for the joints should follow sufficient preparation. Usually, riskier postures are placed toward the end of the practice, followed by simple counterposes to leave the body in a neutral condition.

7. Rest: Use rest appropriately. For example, rest when the breath becomes unsteady, after difficult postures, or when transitioning from one direction to another. The position in which you rest should be one in which you feel relaxed and supported without residual stress. A longer rest at the end of the practice is important in order to both absorb more fully the deeper effects of the practice and to make a transition to the next activity.

In relation to āsana practice, forward bending is considered the hub of the wheel, and back bending, twisting, and lateral bending are considered the spokes. Forward bending is used to transition into and out of other movements. For example, forward bends are used to transition from a back bend to a twist, from a lateral bend to a back bend, and even from a twist to a lateral bend. The following examples can be used as a general guideline for beginning to work with combining postures, respecting their general biomechanical requirements.

Postures can be done standing, kneeling, on the back, inverted, on the stomach, and seated. Standing and kneeling postures are generally useful for warming up the body. Standing postures are stronger, and kneeling postures more stable. Kneeling postures are good for transitioning from standing to lying on the back or stomach. Postures on the back are generally relaxing, although they can be adapted to create deep stretching of the legs, hips, and low back as well as the neck and shoulders. They can also be good preparation for inverted postures. Both headstand and shoulder stand require good preparation and compensation and are therefore usually placed between half and two-thirds of the way through the practice. In the Viniyoga tradition, the shoulderstand is considered the classic counterpose to headstand. Postures on the stomach can be good compensation for the shoulderstand; generally stronger than other postures, they are useful for strengthening and stabilizing the back, and they are also good preparation for deeper back bends. Seated postures generally place more stress on the low back; they can be good compensation for deeper back bends; they are also good preparation for the extended sitting required in prānāyāma and/or meditation; and they are usually placed at the end of the practice.

Respecting these principles, different strategies can be used for combining postures. For example, if you are tired in the morning and want to warm up slowly and then go off to work, you may begin lying on your back, transition through your knees to standing, and end resting on a chair. If, on the other hand, you come home form work in the evening feeling hyperactive, and want to relax before going to sleep, you may begin standing and transition through your knees to lying on your back.