Chapter 4

Chapter 4

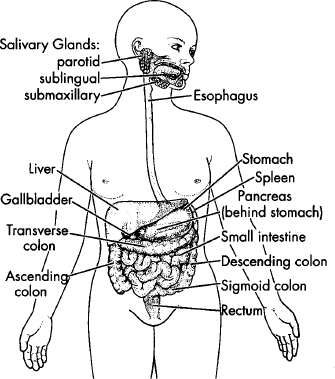

In this system, food is transformed into nourishment for the cells of the body through the functions of various organs, including the mouth, teeth, tongue, salivary glands, throat, stomach, pancreas, liver, gall bladder, the small and large intestines, and the rectum. In a complex chemical process, masticated food is mixed with fluids from the organs and is broken down into nourishing elements, which are absorbed into the bloodstream and then throughout the body, and into wastes, which are eliminated.

The functional processes of the digestive system include the following:

Ingestion, in which food enters the body and begins to be processed by the actions of the jaw, teeth, and tongue, is mixed with secretions of the salivary glands, and is swallowed.

Digestion, in which food is chemically broken down into organic components through the action of acids, enzymes, and buffers secreted by the digestive tract and its accessory organs. In addition to chemical processes there are the mechanical actions of the stomach and intestines, which churn, mix, and move substances through the system.

Absorption, in which these organic elements are moved into the fluid that feeds the cells of the body.

Assimilation, in which the nutrients of the cells are utilized.

Elimination, in which the indigestible wastes from the digestive process are eliminated from the body through processes of dehydration and defecation.

The complex process of turning food into the energy necessary to maintain life and health is regulated by the body’s own natural capacity. Ideally, the body should absorb the maximum nutritional value from the food ingested and efficiently eliminate the indigestible residue. The starting point of this fundamental process is the choice of foods we put into our mouths, as well as the state of our minds and bodies when we eat. That food choice is not always determined by the true needs of the body, and we often are not eating in the optimal frame of mind or physical state.

For so many of us, what we eat is based on convention, habit, or convenience. We often eat on the run, or in the midst of other activity, regardless of our emotional state. The result is often indigestion, which compromises our ability both to absorb the maximum nutritional benefits of our food and to eliminate waste. Improper digestion further results in a weakened condition and an accumulation of toxicity, which can then become the cause of various diseases. These diseases may manifest in the digestive system itself or elsewhere. Of course, problems of the digestive system are not always caused directly by what and how we eat: the body is an integrated whole, and there can be a variety of complex causes leading to any given condition. And there are many different problems that may manifest within the digestive system itself, in one or several of the different digestive organs.

There is an ideal among the yogis that, if we were truly in touch with our bodies, we would instinctively know what foods we needed to eat every time we felt hunger, and that if we are not clear about what we should eat, it would be better not to eat at all. Furthermore, the body and mind should be in a relaxed and pleasant state, without hurry or agitation: if we are excited or upset, either physically or emotionally, we should not be eating. While eating, we should take time to really taste and savor each bite. After eating, there should be relaxed time to digest before we engage in activities that stimulate our systems.

When our digestion is strong, our body feels light and strong. We have plenty of energy. If there are no other complications, we sleep deeply and wake up feeling refreshed. Our skin color is good, our breath and body odor pleasant, and we have a high resistance to disease.

When our digestion is poor, we lack energy. Our sleep may be disturbed, so that we may feel tired even after a full night’s rest. We are likely to accumulate toxins. Our complexion may be pasty, and the odor of our body and breath unpleasant. We are more susceptible to disease and more liable to experience hypersensitivity, irritability, heaviness or dullness, or other manifestations of emotional instability.

We can usually assess the condition of our digestive system by looking at our stools after defecation. This is, of course, a somewhat sensitive topic in our society. However, if we can overcome our squeamishness, much can be learned about how our body is responding to the foods we are eating and the way we are eating them. Some things to look for are whether the stool is too hard and compacted, or too loose, whether it tends to sink or float, and the intensity of its odor. The healthiest stool is well formed, almost like the shape of our intestines, floats, and doesn’t have a very strong odor. This feedback is useful in deepening the process of self-reflection about what and how we eat, and how this contributes to our overall health and well-being.

When we suffer from digestive problems, we can help ourselves through the appropriate combination of lifestyle changes and Yoga practices. This may include changes in diet, taking appropriate supplements and/or medicinal remedies, as well as following the therapeutic guidance of our health practitioners. And, although we cannot solve these conditions exclusively through Yoga practice, we can be sure that a carefully constructed practice of āsanas and prānāyāma makes our whole system function more efficiently and in that way brings more balance into our system. Yoga therapy is not a substitute for medical attention. It is an aid to whatever else we may be doing under our own guidance or under the supervision of a professional.

Although the entire digestive system ideally functions as an integrated whole, problematic conditions can manifest in different organs. All of these conditions can be loosely grouped into two distinct categories: conditions of excess (hyper conditions) and conditions of deficiency (hypo conditions). The ancient yogis used the image of fire (agni) to understand the power of digestion. Following this theory, digestive disorders reflect some imbalance in this internal fire. In hyper functioning, the digestive fire is too strong; in hypo functioning, it is too weak. If the fire is either too strong or too weak, food is not properly broken down into its respective nutrients. As a consequence, the body does not receive the nourishment it needs to thrive and the undigested food becomes a source of toxicity in the body, weakening the system and creating the conditions for disease.

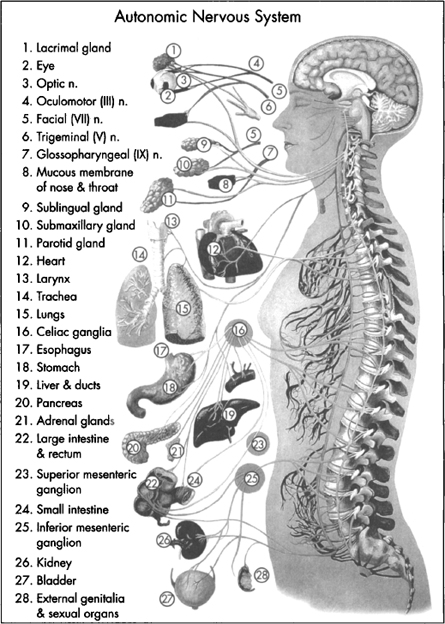

There is a paradox in working therapeutically with these extremes of the digestive system, because we work toward balance—in both cases—through relaxation. The well-known “fight-or-flight” response of our sympathetic nervous system actually stops the digestive process. Our organism developed such that, in cases of emergency, all available energy is redirected to the reflexes and musculature we need for survival. Thus blood is taken out of the digestive system and distributed to the muscles, heart, and brain, and the blood vessels in the digestive system contract, inhibiting digestion. This sympathetic response happens whenever we are under stress. In fact, many digestion problems come from a chronically stressed, over-amped sympathetic nervous system. Symptoms of this “sympathetic overdrive” include feeling stressed, “hyper,” irritable, or rushed, along with eventual fatigue and exhaustion due to depletion of bodily reserves.

The digestive process, a parasympathetic function, works best when we are relaxed. We paradoxically calm the fight-or-flight response (sympathetic function) to stimulate the relaxation response (parasympathetic function), in order to enhance digestion.

Hyper conditions of the digestive system include the following:

Conditions of the stomach: stress-based excessive gastric acid secretion, ulcers, and heartburn (not including cases of hiatus hernia).

Conditions of the intestines: mild chronic diarrhea, Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD).

These conditions often involve cramps, gas, burning sensations, and overall weakness. In these conditions, there is a tendency toward irritability, burning sensations, headaches, and even fevers.

Diarrhea or loose, watery stools. There can be mild but chronic to extreme, acute conditions of diarrhea. At any level, this condition indicates poor absorption of nutrients. The causes of chronic diarrhea can be poor eating habits, including poor food combinations, excessive spices, overeating, eating oily foods, and even eating too fast or in an agitated state of mind. Diarrhea can also be an infectious condition, resulting from impure food or water. This can range from a mild case to the more severe condition of dysentery.

In addition, there are more serious diseases of the intestines, grouped from the more mild irritable bowel syndromes to the more serious inflammatory bowel diseases. IBS symptoms include crampy lower abdominal discomfort and pain, gassiness, diarrhea, or constipation. The more serious IBD conditions include colitis, Crohn’s disease, and diverticulosis. In working with chronic digestive problems, it is important to rule out these more serious conditions first. As with the more serious musculoskeletal problems, Yoga therapy may help as an adjunct to professional medical treatments, but the wrong practice may actually irritate the condition.

When there is any kind of inflammatory disease resulting in diarrhea, there is often excessive heat in the body. In this case we work to reduce the heat (langhana) and soothe the system. We must be extremely cautious about straining the stomach through abdominal work. Thus, simple postures are most useful, such as simple forward bends with the knees bent, gently massaging the stomach, or simple twists, like Jathara Parivrtti. The lateral variation of Jathara Parivrtti is also very useful for increasing circulation without straining the system, although it must be applied cautiously. Lengthening the exhale progressively, and coordinating these simple movements with simple low-pitched sounds will further soothe the system. In acute conditions, we use even simpler techniques.

We should avoid any strong stretching of the belly (as in deep back bends), and always exhale gently, without pulling in the belly.

The practice that follows is presented to illustrate an approach to chronic hyper conditions of the digestive system. Again, it is not prescriptive but rather indicative of an approach to these conditions.

This practice was designed for L.M., a sixty-three-year-old woman who had been diagnosed with Crohn’s disease several years before. She came to see me for a general Yoga practice to support her body while she tried to work on her condition through diet, nutrition, and herbal remedies.

L.M. had a youthful energy and a very positive attitude. As I got to know her, I realized that underneath her happy countenance was an ever-present fear that she would be unable to overcome her condition and would have to have surgery—a possibility that she dreaded. Working on her condition had become the main focus of her life.

L.M. was ready and willing to develop a regular movement and breathing practice. The only structural problem that she had was an unusually deep lumbar scoliosis. I wanted to offer her a practice that would address the scoliosis, gently increase the circulation to her lower abdomen, and help her to deeply relax.

We began very simply, once a week, and over several months we evolved the following practice. She liked the practice, especially the humming, which she said helped her relax more deeply.

As we got to know each other better, we discussed the issue of surgery. I reminded her that a surgeon who specializes in her condition would have a lot of experience and that the technology was getting more and more sophisticated every year. I told her that I hoped she could open her heart to the possibility that she might have to go that route.

The day came when she told me that her doctor had scheduled the surgery. She told me that, though she was afraid, she was hopeful. The surgery was successful, and L.M. tells me she is so relieved to return to a normal life. She is still careful about her diet, but she says she no longer “obsesses” about her condition. She still does her Yoga practice and comes to work with me several times each year.

1.

POSTURE: Ekapāda Apanāsana.

EMPHASIS: To gently compress belly while progressively extending exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with right knee bent toward chest, right foot off floor, left knee bent and left foot on floor. Place both hands on right knee.

On exhale: Pull right thigh gently but progressively toward chest.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat on other side.

NUMBER: 8 times each side, one side at a time.

DETAILS: On exhale: Pull gently with arms, keeping shoulders down on floor and relaxed. Press low back down into floor, drop chin slightly toward throat. Progressively lengthen exhale with each successive repetition.

2.

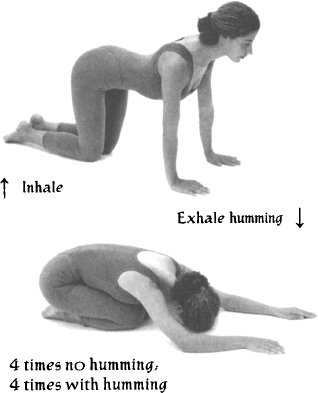

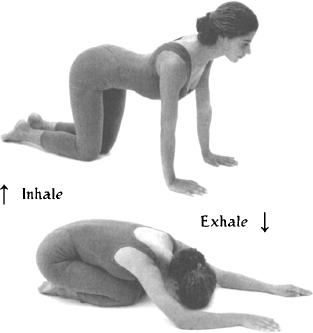

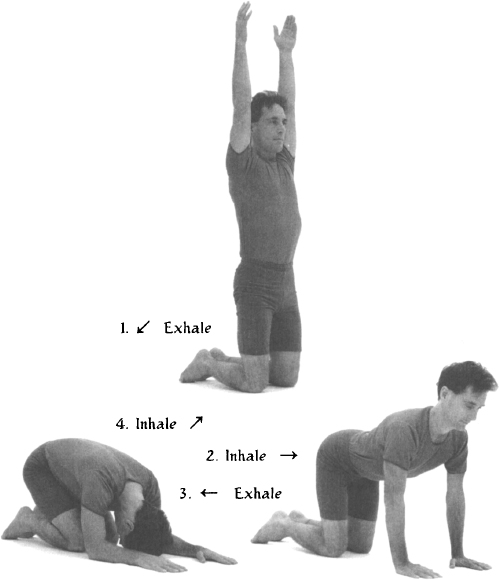

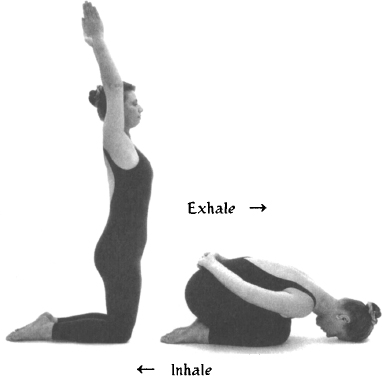

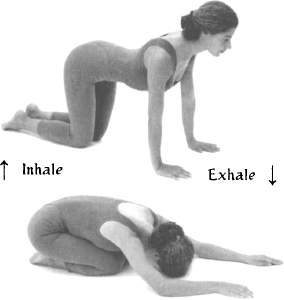

POSTURE: Cakravākāsana.

EMPHASIS: To gently compress and stretch belly while working with humming sound to soothe belly. TECHNIQUE: Get down on hands and knees, with shoulders vertically above wrists and with hips above knees.

On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly.

Exhale with a soft, low-pitched humming sound while gently contracting belly, rounding low back, and bringing chest toward thighs.

NUMBER: 4 times with no humming; 4 times with humming.

DETAILS: On inhale: Avoid pulling spine with head, overarching neck. Lead with chest, keeping chin slightly down. Avoid overarching low back; rather, feel stretching in belly. On exhale: Round low back without collapsing chest over belly. Avoid increasing curvature of upper back. Let chest lower toward thighs sooner than hips toward heels.

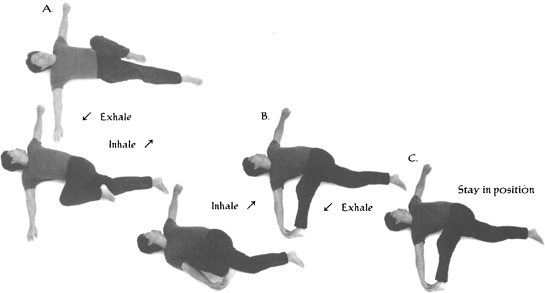

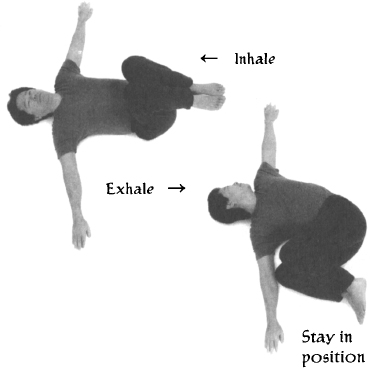

POSTURE: Jathara Parivrtti variation.

EMPHASIS: To gently twist and compress belly, progressively increasing number of breaths while staying in posture.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back with both knees bent, thighs lifted toward chest, both feet off ground, and arms out to sides, slightly less than right angles to torso.

On exhale: Bring both knees toward floor on right side of body, twisting abdomen and simultaneously turning head left.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: Stay in twist 1,2,3, and then 4 full breaths on each side, alternating sides.

DETAILS: On exhale: Throughout movement, keep knees at an angle to torso that is less than ninety degrees.

4.

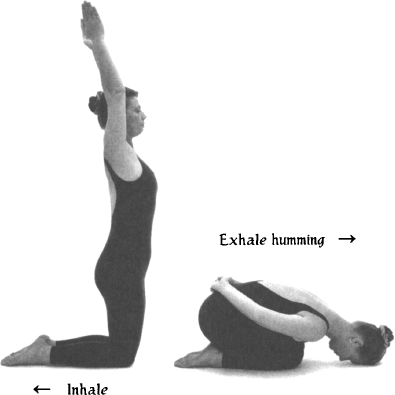

POSTURE: Vajrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To gently compress and stretch belly, working with humming sound.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward with a soft, low-pitched humming sound while sweeping arms behind back and bringing hands to sacrum, palms up.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bring chest to thighs before hips to heels. Rotate arms so palms are up and hands rest on sacrum. On inhale: Expand chest and lift it up off knees as arms sweep wide.

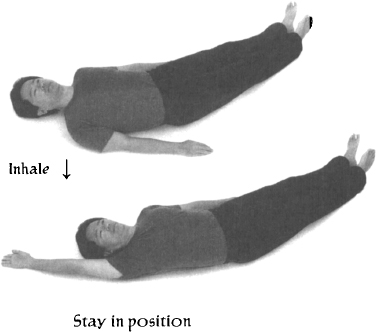

POSTURE: Jathara Parivrtti variation.

EMPHASIS: To gently compress and stretch belly, using belly breathing technique.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with legs straight and arms flat and at a small angle from sides.

Walk both feet in small increments to left until right side of lower torso and hip are gently stretched. Raise right arm up over head.

Stay and breathe deeply, gently protruding belly on inhale.

Return to starting point.

Repeat on other side.

NUMBER: Stay 8 deep breaths each side.

DETAILS: GO only as far with legs as allows low back and hips to stay stable on floor. Avoid increasing arch of low back.

6.

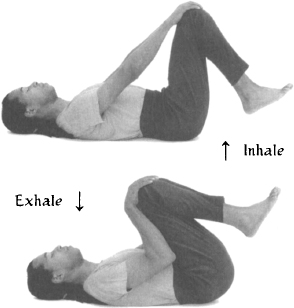

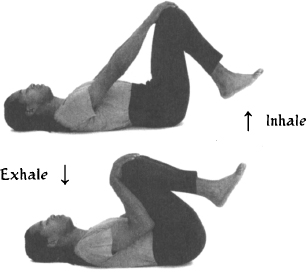

POSTURE: Apānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To gently compress belly while progressively extending exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with both knees bent toward chest and feet off floor. Place each hand on its respective knee.

On exhale: Pull thighs gently but progressively toward chest.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 12 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Pull gently with arms, keeping shoulders relaxed and on floor. Press low back down into floor and drop chin slightly toward throat. Progressively lengthen exhale with each successive repetition.

7.

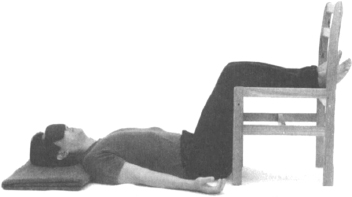

POSTURE: Śavāsana with support.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms at sides, palms up, and legs resting comfortably on a chair. Cover closed eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body.

DURATION: Minimum 5 minutes.

Hypo conditions of the digestive system, which involve either decreased digestive ability or decreased mobility, include the following:

Conditions of the stomach and small intestines: lack of digestive enzyme, low secretion of gastric acid (hypochlorhydria—a condition that often occurs in old age).

Conditions of the large intestines: constipation.

These conditions involve abdominal pain, gas, and indigestion (feeling bad after eating). In this condition, there is a tendency toward heaviness, lack of energy, and bloating.

Constipation involves infrequent, sluggish, and sometimes painful elimination. There may be mild to severe conditions of constipation. Chronic constipation can be caused by poor eating habits, delaying or suppressing the urge to eliminate, as well as excessive tension and anxiety. At any level, constipation indicates an inadequate elimination of wastes from the body.

Unlike hyper conditions, where we want to soothe the system, in hypo conditions we can work the abdominal area more directly in order to stimulate digestion and the movement (peristalsis) of wastes along the digestive tract. We work with a firm pulling in of the belly on exhalation, coordinated with forward bends and twists. We can even do forward bending and/or twisting postures while holding the breath out after exhalation. It is also often helpful to include some stretching of the belly through gentle backward bends. Finally, the use of segmented (krama) breathing on exhalation is also very useful for these conditions.

The practice that follows is presented to illustrate an approach to chronic hypo conditions of the digestive system. As with the previous practice, it is not prescriptive but rather indicative of an approach to these conditions.

This practice was developed for D.M., a thirty-six-year-old woman working in the commodities market. She told me she spent the better part of each day in front of a computer terminal and on the phone. She said her job was very stressful. She told me that she had been constipated for years, and although increasing the fiber intake in her diet had helped, the problem persisted. She also told me she went to the gym regularly to do low-impact aerobics.

D.M. was in good physical condition and did not suffer from chronic aches and pains. I noticed that, though she was physically toned, there was a lot of tension in her musculature—especially her jaw. I decided to develop a langhana practice for her, emphasizing exhalation, movement on hold after exhalation, forward bends, and twists. Since she regularly worked out, the main focus for this practice was to help her relax generally, and to increase circulation to and relax the lower abdomen specifically.

Over several months, we evolved the following practice. D.M. was very disciplined and was able to practice daily. She told me that often, within an hour or two after practice, she was able to have a satisfying bowel movement. I saw her again about a year after our last session together, and I asked her how she was doing. She told me that when she practices, she has no problems, but if she stops, the constipation comes back.

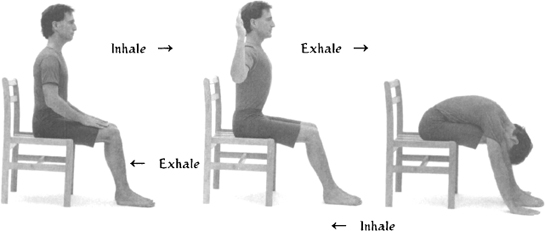

1.

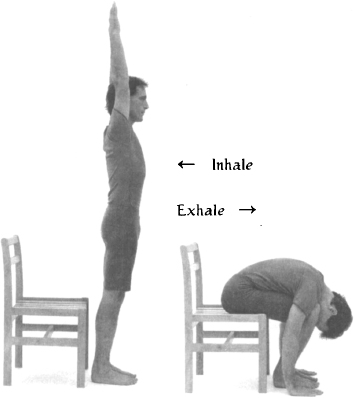

POSTURE: Vajrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To compress belly and progressively extend exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, sweeping arms behind back, bringing hands to sacrum with palms up.

Make each exhale progressively longer.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bring chest to thighs before buttocks to heels. Rotate arms so palms are up and hands rest on sacrum. On inhale: Expand chest and lift it up off knees as arms sweep wide.

2.

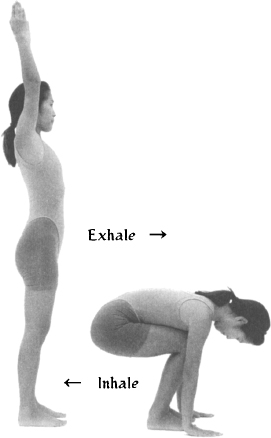

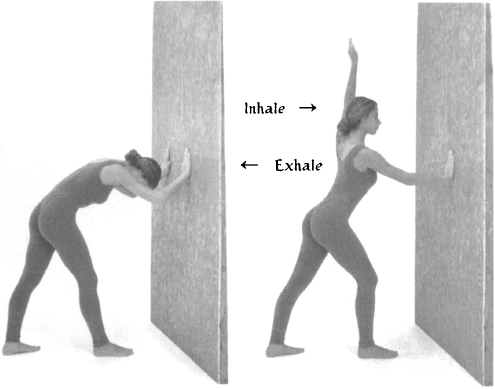

POSTURE: Uttānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To compress belly. To introduce movement on hold after exhale.

TECHNIQUE:

A: Stand with feet slightly apart, arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, bending knees slightly, bringing chest to thighs, and palms to sides of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

B: Exhale fully in starting position.

Holding breath out after exhale, bend forward, keeping belly held in.

On inhale: Return to starting point.

NUMBER: A four times. B four times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bend knees to facilitate stretching of low back. Move chin down toward throat. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back. Keep knees bent until end of movement.

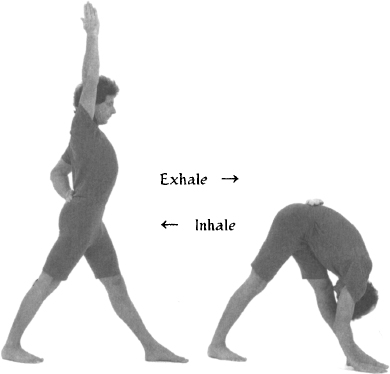

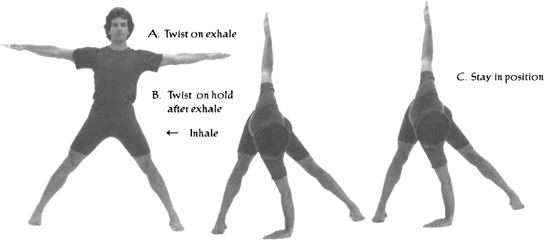

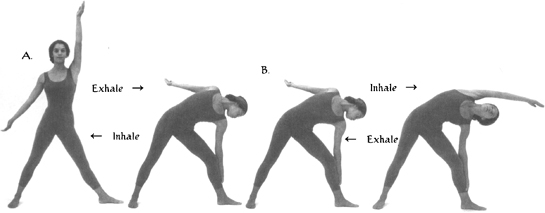

POSTURE: Parivrtti Trikonāsana.

EMPHASIS: To twist and compress belly. To achieve subtle torsion on hold after exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with feet spread wider than shoulders, arms out to sides and parallel to floor.

On exhale: Bend forward, bringing left hand down to floor, right arm pointing upward, twisting shoulders right. Turn head down toward left hand.

Holding breath out after exhale 4 to 6 seconds, twist slightly further.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat on other side.

NUMBER: 6 times each side, alternately.

DETAILS: On exhale: Initiate and control torsion through belly contraction. Rotate shoulder girdle until right shoulder is vertically above left. On inhale: Untwist torso while returning to starting position.

4.

POSTURE: Cakravākāsana.

EMPHASIS: To make transition from standing to supine position. To stretch rib cage on inhale and low back on exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Get down on hands and knees, with shoulders vertically above wrists and with hips above knees.

On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly.

On exhale: Gently contract belly, round low back, and bring chest toward thighs.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lead with chest, keeping chin slightly down. Avoid compressing low back; rather, feel chest expanding. On exhale: Round low back without collapsing chest over belly. Avoid increasing curvature of upper back. Let chest lower toward thighs sooner than hips toward heels.

POSTURE: Jathara Parivrtti.

EMPHASIS: To twist and compress belly. To move on hold after exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms out to sides and with left knee pulled up toward chest.

A: On exhale: Twist, bringing left knee toward floor on right side of body while turning head to left.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 4 times.

B: Exhale fully in starting position. Holding breath out after exhale, twist again to right, holding belly in.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 4 times.

Repeat on other side.

DETAILS: On exhale: When twisting right, keep angles between left arm and torso and between left knee and torso less than ninety degrees.

6.

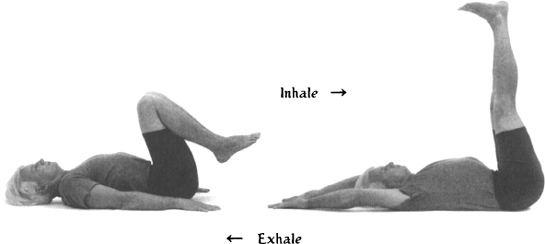

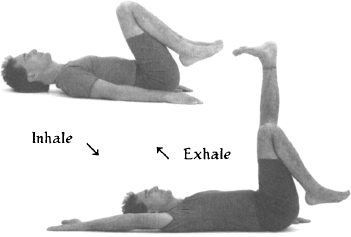

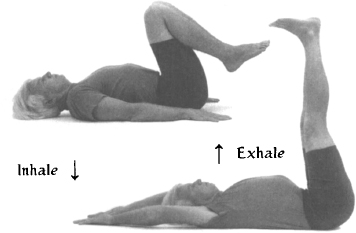

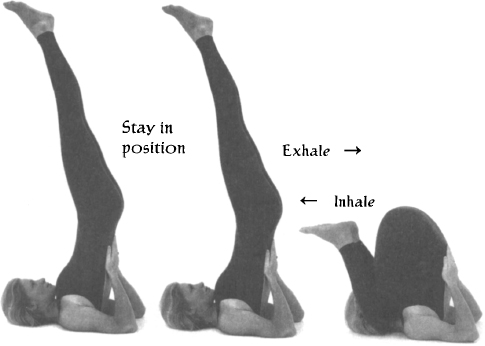

POSTURE: Ūrdhva Prasārita Pādāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stimulate lower abdomen, extend spine and flatten it onto floor, and stretch legs.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, legs bent, and knees in toward chest.

On inhale: Raise arms upward all the way to floor behind head, and legs upward toward ceiling.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat 4 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Flex feet as legs are raised upward. Slightly bend knees, keeping angle between legs and torso less than ninety degrees. Push low back and sacrum downward. Bring chin down.

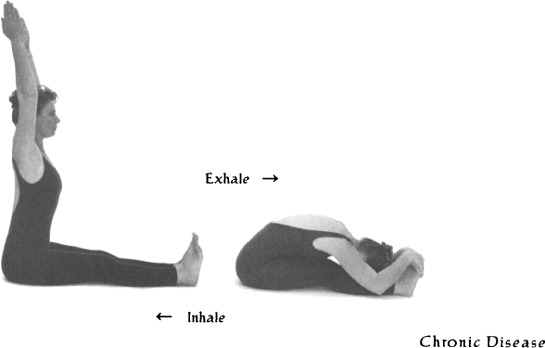

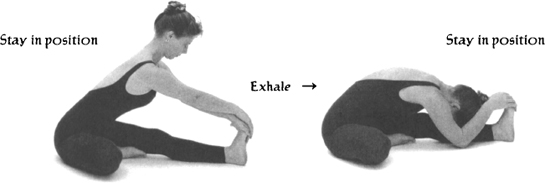

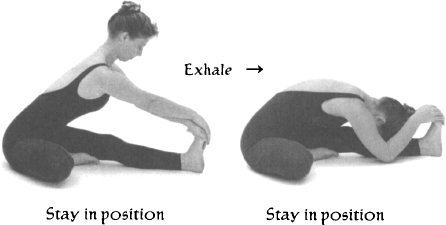

POSTURE: Paścimatānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To compress belly and stretch back.

To move on hold after exhale.

TECHNIQUE:

A: Sit with legs forward, back straight, and arms raised over head.

On exhale: Bending knees slightly, bend forward, bringing chest to thighs, and palms to balls of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

B: Exhale fully in starting position.

While holding after exhale, bend forward, keeping belly held in.

On inhale: Return to starting point.

NUMBER: A four times; B four times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bend knees to facilitate stretching low back and bring belly and chest to thighs. Move chin down toward throat. Feel like diaphragm moves up while holding after exhale. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back.

8.

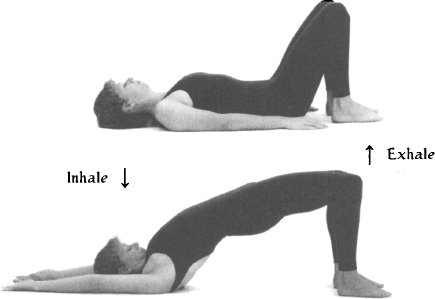

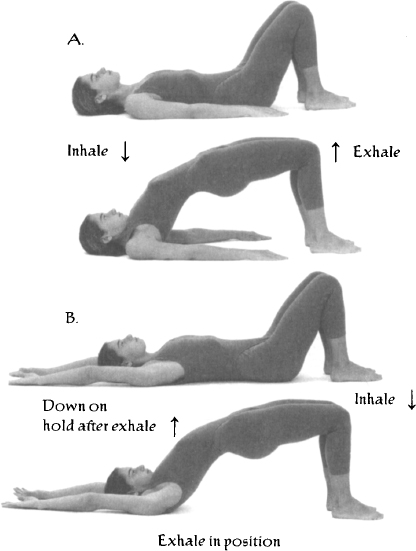

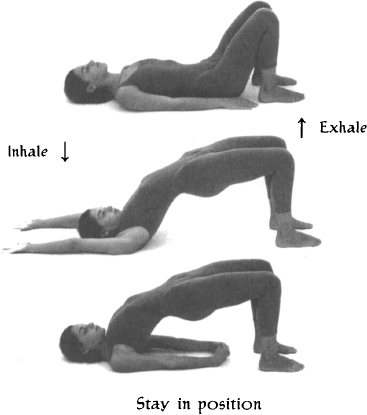

POSTURE: Dvipāda Pītham.

EMPHASIS: To relax back and stretch belly.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, knees bent, and feet on floor, slightly apart and comfortably close to buttocks.

On inhale: Pressing down on feet and keeping chin down, raise pelvis until neck is gently flattened on floor, while raising arms up overhead to floor behind.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift spine, vertebra by vertebra, from bottom up. On exhale: Unwind spine, coming down vertebra by vertebra.

POSTURE: Śavāsana with support.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms at sides, palms up, legs slightly apart, with a support under the knees. Close eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body.

DURATION: Minimum 5 minutes.

10.

POSTURE: Prānāyāma-Viloma Krama.

EMPHASIS: To stimulate and compress belly through segmented exhale.

TECHNIQUE:

Inhale deeply and fully.

Exhale 1/2 of breath in 4 to 6 seconds.

Pause in middle of exhale for 4 to 6 seconds.

Exhale remainder of breath in 4 to 6 seconds.

Hold breath out 4 to 6 seconds.

Inhale deeply.

Repeat.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: Control first segment of exhale from pubic bone to navel. Control last segment of exhale from navel to solar plexus.

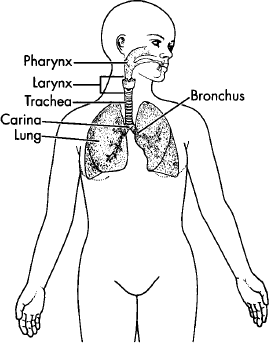

Respiration is essential for the life and function of every cell in our bodies. Cells utilize oxygen and produce carbon dioxide, and it is through respiration that the cells obtain the one and eliminate the other. The respiratory system consists of the nose, nasal cavities, sinuses, pharynx, larynx (voice box), trachea (wind pipe), and the lungs—including the air passages (bronchi), the air sacs (alveoli), and the surrounding membranes (pleura). The upper part of the respiratory tract serves to filter, warm, and humidify incoming air. The lower part provides surfaces through which the vital exchange of gasses occurs.

There are actually three levels of the respiratory process:

Ventilation refers to the twofold, mechanical process of inhalation and exhalation.

Delivery refers to the vital exchange (by diffusion) and transport (via circulation) of gasses between the lung surfaces and the bloodstream, between the bloodstream and the fluids surrounding the cells, and between those fluids and the cells themselves.

Utilization refers to the use of oxygen by the cells for metabolic processes, primarily the production of energy. It is through this cellular metabolism that the cells generate, store, and use energy to support and maintain bodily function.

This threefold process of respiration nourishes and purifies the blood, and thereby the entire body. The cardiovascular system provides the link between these three processes. Through inhalation, oxygen in the air passes through the lungs, into the bloodstream, and then to every cell of the body. Through exhalation, waste material (carbon dioxide) is returned from the cells, via the bloodstream, to the lungs, and is exhaled out of the body.

In addition to their vital respiratory function, the pleural membranes protect the delicate lung surfaces from changes in temperature, dehydration, and the presence of pathogens. The larynx, which includes the vocal chords, enables us to generate vocal sounds. The nose filters the air, preventing airborne particles, insects, et cetera, from entering the deeper nasal cavity and from there into the lungs.

In normal activity, the cellular demand for oxygen is met by automatic, reflexive breathing. In this process, the inhalation phase, which is active, lasts for approximately two seconds, and the exhalation, which is passive, lasts for approximately three seconds. The normal rate of respiration for an adult is between twelve and eighteen cycles per minute.

When we are exercising or otherwise stressing the system, there is significantly greater demand for oxygen, and our respiratory rate increases accordingly. When this occurs, there is a homeostatic integration of the respiratory rhythm and the cardiovascular response, so that the increased respiratory rate and the cardiac circulation are coordinated. In fact, we measure the quality of our aerobic workouts by this increase, usually measured by the increased heart rate.

It is interesting to notice that these increases in respiratory and cardiac rates occur both when we are very physically active and when we are strongly stimulated emotionally. When we are physically active, the muscles function as auxiliary pumps for the heart, assisting circulation. In this case, there is an overall developmental conditioning of the body. If, on the other hand, we are chronically emotionally stressed without being physically active, the respiratory and cardiac rates have to increase to meet the increased oxygen demand without the support of the musculature. In this case, the systems of the body are taxed in an unhealthy way.

There is an old notion among the yogis that we are all born with a certain number of breaths in this life.

The goal of the yogis was to slow down the natural respiratory rate and to develop the capacity to engage in increasingly demanding muscular activities with progressively deeper and slower breaths. This represents a somewhat different view of aerobic conditioning than the one current today, though both are oriented to the efficient oxygenation of the entire system and the development of cardiovascular fitness and stamina. Public recognition of the importance of aerobic exercise for maintaining optimal health is on the rise. Yet many people have not been able to integrate this important practice into their lives.

Usually, we are so caught up in the momentum of our activities that we are unaware of our breathing patterns. It is common for people to say, when reflecting on their breath, “I don’t breathe.” Of course, we are all always breathing in some fashion, but the normal patterns of breathing are usually shallow, restricted, and punctuated with holding patterns. The ancient Yoga authority Patañjali declared that these normal, disturbed, irregular habits of breathing are themselves symptoms of deep imbalances in our system. They can either indicate the presence of various mental afflictions, physical diseases, or be contributing factors to lowering our immunity and increasing our susceptibility to such diseases. When our breathing patterns are weak, we may have low energy and find ourselves easily fatigued and more emotionally stressed. When, on the other hand, our breathing patterns are deep and strong, we have increased endurance, stamina, and a sense of well-being.

In addition to developing poor breathing habits, many of us live and work in relatively toxic environments, where the need for the purification that occurs through good aerobic activity is even greater. In addition, habits like smoking tax the respiratory system and increase toxicity in the body. In fact, lung cancer is on the rise worldwide, and the vast majority of lung cancers have been directly linked to cigarette smoking. Smoking makes the air we take into our lungs dryer and contaminates it with particles that have been shown to be carcinogenic.

There are many different factors that, in combination, reduce the efficiency of the respiratory system. When this vital function is impaired, the rest of our system is negatively impacted and there are various problematic conditions that may manifest within the respiratory system itself.

Structurally, breathing is inhibited due to weak respiratory muscles, rigid and inelastic structures of the chest, and poor lung capacity. The result is often poor ventilation and oxygenation. This condition is often present when there is a sunken or shallow chest. Symptoms include weakness, low breath endurance, and fast or shallow breathing.

Infectious conditions, directly linked to a weakened immune response, that attack the respiratory system include common colds, coughs and flus, or, at a more serious level, bronchitis, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. Symptoms of these conditions range from runny nose or sore throat to accumulation of mucus and phlegm, fevers, difficulty in breathing, cough, wheezing, weakness, and chest pain.

Many allergic conditions, also linked to a defect in the immune system, attack the respiratory system. Common allergies such as allergic rhinitis or hay fever produce similar symptoms, including sneezing, wheezing, accumulation of mucus and phlegm, feeling of tightness in the chest, and difficulty in breathing. Bronchial asthma, which is less common but still widespread, is a more serious form of allergic reaction. Asthma sufferers have episodes of mild to severe breathlessness and wheezing. These episodes, commonly referred to as asthma attacks, are characterized by narrowing of the air passages and difficulty in exhalation. These attacks are usually recurring and are variable in severity. Although acute asthma can indeed be life threatening, there is no actual damage to the lung tissue.

More serious, long-term conditions, which result in actual physical damage to the respiratory tract, are chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Chronic bronchitis is the long-term inflammation of the bronchial passages. Symptoms of this condition include restricted breathing and a chronic cough that produces a thick, greenish-yellow mucus. Emphysema is a disease in which the air sacs (alveoli) are destroyed, inhibiting the vital gas exchange with the bloodstream. Symptoms of this condition include laborious breathing, gasping sounds with each breath, and debilitating weakness.

The common denominator of these conditions is the obstruction of the air flow either into or out of the lungs, or the inability of the lungs to efficiently exchange gases into and out of the bloodstream. In addition, there are the shared symptoms described above.

Breathing is perhaps the single most important activity we do to maintain our lives. When our capacity to breathe is obstructed, it is a very frightening experience. In all acute conditions, it is important to be under the guidance of medical professionals. Even in the case of chronic asthma, sufferers should receive the benefit of modern medical care. In acute asthma attacks, the use of bronchodilator drugs can be life-saving.

The causative factors of these respiratory conditions are complex. They are clearly influenced by hereditary tendencies, improper diet, poor digestion, smoking, excessive physical exertion, lack of adequate physical exercise, poor posture, exposure to weather extremes, air pollution, infections, tension, and emotional stress.

According to the Yoga tradition, these conditions are often linked to the digestive system. With improper digestion, mucus and phlegm are produced in the stomach and accumulated in the lungs. A careful assessment of our diet, as well as other lifestyle adjustments, are essential ingredients to any program of self-improvement.

In addition to these lifestyle adjustments, and in coordination with appropriate medical care, a carefully constructed Yoga therapy program will strengthen our systems and even help people with chronic conditions to become more independent of medications.

Allergies that attack the respiratory system may be considered a kind of hypervigilance of the immune system. An asthma attack is a bronchial spasm in response to an irritation. In this case, even though the bronchial spasm is parasympathetic, the direction of practice is first to soothe and then to strengthen the system, giving particular attention to developing the capacity for exhalation.

Cases where the breathing is structurally restricted, on the other hand, may be considered hypo or deficient conditions. Here the direction of practice is to mobilize the rib cage, and particular attention is given to developing the capacity for inhalation.

In the respiratory system, however, this division of diseases and symptoms into excessive (hyper) and deficient (hypo) is not a perfect fit. Many people suffering from asthma have restricted chest mobility and would equally benefit from developing their capacity to inhale. And those with restricted chests will likewise benefit from strengthening their exhale. Therefore, the best approach for any specific condition must be developed in the context of individual body type, structural capacity, and breathing habits.

In fact, everybody will benefit from the development of their breathing capacity. The core ideas in Yoga therapy for working with respiratory conditions are relaxation, developing the breath capacity, and, in particular, achieving greater control of the diaphragm. In certain conditions, it may be more appropriate to emphasize strengthening exhalation, and in other conditions, inhalation. As we have seen, in Yoga breath training, we develop the capacity to expand the chest and abdomen on inhalation and to pull the belly in on exhalation. There are different techniques that may be applied in different situations, and we learn through training to utilize the most appropriate method for each situation.

In the sequences that follow, we will offer practices designed to increase confidence, strengthen the body, increase the capacity for inhalation and exhalation, increase circulation to all the organs, move the body fluids, and facilitate digestion and elimination.

In the case of the asthmatic, for example, the normal breathing pattern is often reversed, with the belly coming in on inhalation and going out on exhalation. The first step in working with these conditions is breathing reeducation. We begin by training in “abdominal” breathing, where the abdomen goes out on inhalation and is pulled in on exhalation. This is developed with the help of simple positions and movements.

The next step is increasing the ability to deepen and control exhalation. As we have seen, exhalation is considered a technique of relaxation. This is achieved through the use of simple postures that facilitate exhalation and help the diaphragm move fully upward.

As breath control increases, we can introduce stronger positions that place a greater demand on breathing capacity. We then will begin holding the breath after exhalation.

Fear and anxiety are strong factors in any restricted breathing, and they must be respected. Progress in this direction is gradual and should proceed without forcing the system. The following sequence is illustrative of an approach to working with asthma.

The sequence that follows was developed for C.D., a forty-three-year-old woman who, when she first came to study with me, was a personnel manager for a regional telephone company. She had been suffering from asthma for many years and also complained of chronic pain in her shoulders.

C.D. had taken some group classes at our school while she was on vacation with her family. She liked our gentle approach and was hopeful for some improvement in her long-standing condition. I had the opportunity to work with her on and off over many years, both at our school and in various other cities where I teach. Her dedication to the study and practice of Yoga was clear, and, in time, she completed an extensive training program with me. She eventually left her job and is now a full-time Yoga teacher. Through her experience of learning to manage her own asthma, she has become a great resource for others suffering with the same condition.

C.D.’s faith in Yoga gave her the discipline to practice regularly for many years. When we first started working, she had a lot of fear about both her asthma and her shoulder. I noticed that the movement of her rib cage was severely restricted and that her whole upper body was weak. Any attempt to expand her chest on inhale created breathing spasms, and she was also unable to come forward in Cakravākāsana without breathing spasms.

We began with very simple movements to mobilize her chest and upper back without any emphasis on inhalation. Our next step together was to emphasize exhalation in simple forward bends. As her confidence grew, we then added inhalation techniques coordinated with arm movements. My next aim was to help her increase the mobility in her upper back and to release tension in her neck.

Over time she let me know which āsanas felt the best to her, and the following sequence emerged as the foundation for her daily practice. Over the years I noticed that she never failed to have a plastic water bottle with her. As her fear about her shoulders lessened, I suggested that she keep two of them with her while she practiced. I asked her to hold one in each hand while she did her forward bends, both seated and standing. Over time she put progressively more water in them. After her practice, I asked her to drink some of the water. She liked this idea very much. Though her asthma is still with her, she is able to manage it much better now and has much more confidence in herself. She is able to do a deep-breathing practice without spasm on most days. She tells me she feels much stronger, and her shoulder pain is, for the most part, a memory.

1.

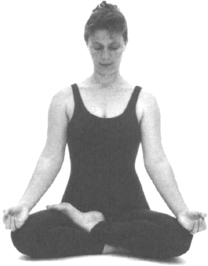

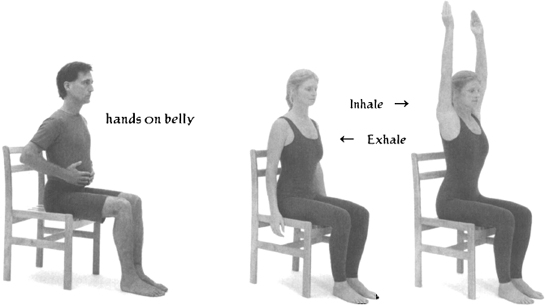

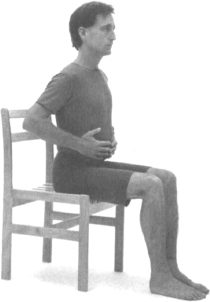

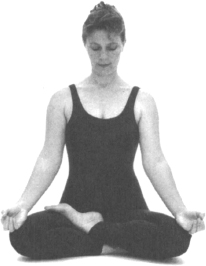

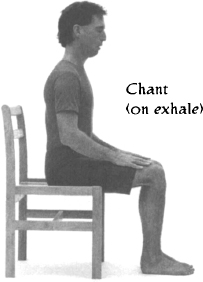

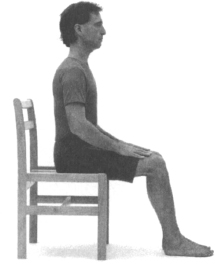

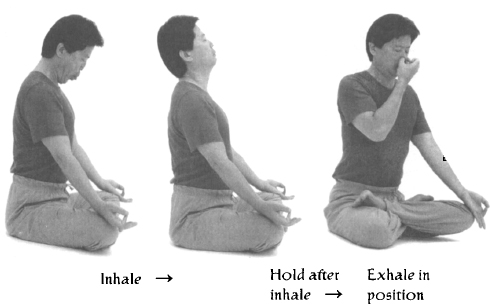

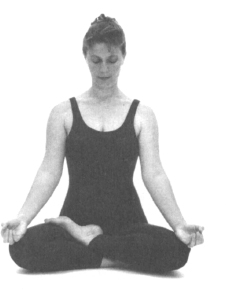

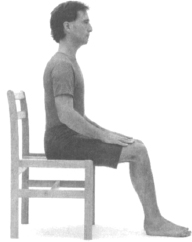

POSTURE: Seated breathing.

EMPHASIS: To train abdominal breathing.

TECHNIQUE: Sit forward on a chair with spine erect and hands placed on abdomen.

On exhale: Gently pull belly in toward spine.

On inhale: Gently release belly and let it come out.

NUMBER: 12 times.

DETAILS: Make both inhale and exhale long and smooth.

2.

POSTURE: Vajrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To compress belly. To gently mobilize rib cage. To introduce lengthening of exhalation.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, sweeping arms behind back, bringing hands to sacrum with palms up.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Make exhalation progressively longer with each repetition. Bring chest to thighs before buttocks to heels. Rotate arms so palms are up and hands rest on sacrum. On inhale: Expand chest and lift it up off knees as arms sweep wide.

3.

POSTURE: Uttānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To strengthen arms, shoulders, and upper back (holding water bottles). To compress belly and continue lengthening exhalation.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with feet slightly apart, arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, bending knees slightly, bringing chest to thighs and bottles to sides of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Make exhalation progressively longer with each repetition. Bend knees to facilitate stretching of low back. Move chin down toward throat. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back. Keep knees bent until end of movement.

POSTURE: Utthita Trikonāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch and mobilize rib cage.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with feet spread wider than shoulders, left foot turned out at ninety-degree angle to right foot, left arm over head, and right arm out to the side with palm up.

On exhale: Bend laterally, bringing left hand below left knee, while twisting shoulders right. Turn head down toward left hand.

On inhale: Raise right arm up and forward, turning head to follow hand.

On exhale: Return right arm out to the side, turning head down to left foot.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times each side.

DETAILS: On exhale: Pull pubic bone slightly up to avoid increased lumbar curve. Bend left knee slightly. Keep shoulders in same plane as hips. On inhale: Stretch intercostal muscles fully on up side.

5.

POSTURE: Cakravākāsana.

EMPHASIS: To gently compress and stretch belly. To introduce humming on exhale. To transition from standing lateral bend to seated twist.

TECHNIQUE: Get down on hands and knees, with shoulders vertically above wrists and with hips above knees.

On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly.

On exhale: Gently contract belly, round low back, and bring chest toward thighs while making a gentle, low-pitched humming sound.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lead with chest, keeping chin slightly down. Avoid compressing low back; rather, feel chest expanding. On exhale: Round low back without collapsing chest over belly. Avoid increasing curvature of upper back. Let chest lower toward thighs sooner than hips toward heels.

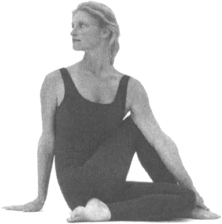

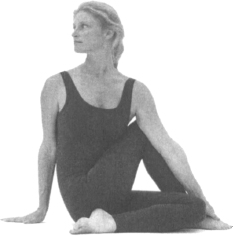

POSTURE: Ardha Matsyendrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To fully exhale by deeply twisting belly and moving diaphragm upward. To introduce hold after exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with left leg folded on floor, left foot by right hip, right knee straight up, right foot crossing over on outside of left knee, right arm behind back with palm down on floor by sacrum, left arm across outside of right thigh, and left hand on right foot.

On inhale: Extend spine upward.

On exhale: Twist torso and look over right shoulder.

Hold breath 4 to 6 seconds after exhale.

NUMBER: 8 breaths each side.

DETAILS: On exhale: Control torsion from deep in belly, using arm leverage only to augment twist. On inhale: Subtly untwist body to facilitate extension of spine.

7.

POSTURE: Paścimatānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To strengthen arms, shoulders, and upper back (holding water bottles). To compress belly and stretch and strengthen back. To deepen hold after exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with legs forward, back straight, and arms raised over head.

On exhale: Bending knees slightly, bend forward, bringing chest to thighs, and bottles to feet.

Hold after exhale 4 to 6 seconds.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bend knees to facilitate stretching low back and bring belly and chest to thighs. Move chin down toward throat. Feel like diaphragm moves up while holding after exhale. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back.

POSTURE: Śavāsana.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms at sides, palms up, and legs slightly apart. Close eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body.

DURATION: Minimum 5 minutes.

9.

POSTURE: Prā āyāma—Viloma Krama, three-stage exhale.

āyāma—Viloma Krama, three-stage exhale.

EMPHASIS: To stimulate and compress belly through segmented exhale.

TECHNIQUE:

Inhale deeply and fully.

Exhale 1/3 of breath in 3 seconds.

Pause 3 seconds.

Exhale another 1/3 of breath in 3 seconds.

Pause 3 seconds.

Complete exhale in 3 seconds.

Inhale deeply and repeat.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: Contract abdomen from pubic bone to solar plexus in 3 stages. Skip the 3-second pause after the third stage of exhale.

In the case of restricted chest mobility, for example, practice is designed to progressively expand the structures of the rib cage, strengthen the respiratory muscles, and deepen the capacity for inhalation. The first step is to improve expansion of the chest on inhalation. This is facilitated by the use of simple arm movements, coordinated with breathing.

As breath control increases, we can introduce stronger positions that place a greater demand on breathing capacity. Then we will introduce holding the breath after inhalation.

The next step is increasing the ability to deepen and control the inhalation. This is achieved through the use of simple postures that facilitate inhalation and help the chest expand even more fully.

This sequence was developed for G.T., the nineteen-year-old nephew of one of my students from Italy. He came to me on the advice of his aunt, who had been studying with us for some time. She was concerned that he was drifting without any direction and thought that maybe Yoga would help. G.T. came with an open and sincere attitude, though he was both uncertain and confused about his future. He had been to the United States when he was twelve, spoke some English, and liked the idea of learning some more.

Initially I asked him about how he was feeling and what he would like to do with me. His main physical concern seemed to be the narrowness of his chest, and he wondered if he could do something to help expand and develop it. He didn’t talk to me about any other concerns. My impression was of a sweet and rather timid young man.

As we began working together, I discovered that he had some difficulties at school and had left before graduating. His main interest seemed to be art, and he was quite talented as a graphic artist. He had held odd jobs for the past year or two since he left school. He was not involved in any sport or physical activity.

As we were in Italy that year for about three months, I was able to follow his progress until I felt he could understand and practice the brahmana sequence below on his own. It took us the full three months, working once a week, to reach this point.

The emphasis of our work was postures that place a demand on the larger muscles of his body and postures that expand the chest. At the same time I wanted to keep the practice relatively short and uncomplicated, since I knew I wouldn’t be able to check in with him regularly.

I somehow felt that he needed more physical and mental stimulation and hoped he would be able to find some direction. The area in Italy that he is from is hilly and full of villas, churches, and chapels. He told me about some of the special hidden places he knew of and, with my hopes for him in mind, I asked him to take me to one. Instead of driving up the steep hill to the parking lot, I suggested we walk. It was interesting for me to notice how winded he was and, at the same time, how excited to arrive at this hidden spot. I asked him if there were others around, and he said many. Since he obviously enjoyed these special places and recognized the need for more exercise, I suggested that he go on small excursions once a week, hiking up to the various sites.

G.T. enjoyed both the Yoga practice and the excursions and was able to keep them up for quite some time after I left Italy. I was happy to hear that he went back and finished school. As of this writing, G.T. is twenty-two years old and is studying art history and painting at a university in Italy.

1.

POSTURE: Prā āyāma—Anuloma Krama, two stages.

āyāma—Anuloma Krama, two stages.

EMPHASIS: To expand chest and deepen inhalation capacity.

TECHNIQUE:

Exhale deeply and fully.

Inhale 1/2 of breath in 4 to 5 seconds.

Pause 4 to 5 seconds.

Inhale remainder of breath in 4 to 5 seconds.

Pause 4 to 5 seconds.

Exhale slowly and fully.

Repeat.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Expand chest from pit of throat to sternum. Then expand abdomen from solar plexus to pubic bone.

POSTURE: Vajrāsana/Cakravākāsana Vinyāsa.

EMPHASIS: To warm up body. To introduce lengthening of inhale.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, bringing arms to floor in front of you.

On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly, coming forward onto hands.

On exhale: Tighten belly, round low back, and bring chest toward thighs.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Make inhalation progressively longer with each repetition. Bring chest to thighs before hips to heels. Avoid pulling spine with head, overarching neck. Lead with chest, keeping chin slightly down. Avoid overarching low back; rather, feel stretching in belly. On exhale: Round low back without collapsing chest over belly. Avoid increasing curvature of upper back. Let chest lower toward thighs sooner than hips toward heels.

3.

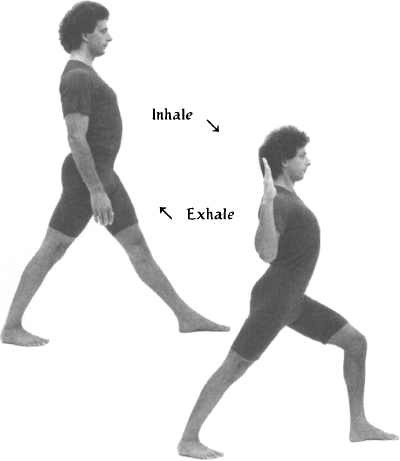

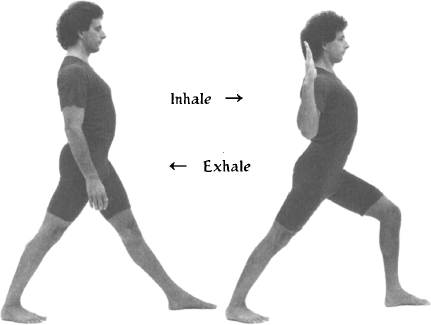

POSTURE: Vīrabhadrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To strengthen muscles of back and legs.

To expand chest and flatten upper back. To increase hold after inhalation.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with left foot forward, feet as wide as hips, and arms at sides.

On inhale: Simultaneously bend left knee, displace chest slightly forward and hips slightly backward, bringing arms out to sides and shoulders back.

After inhale: Hold breath 2, 4, and 6 seconds, 2 times each, progressively.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times each side.

DETAILS: On inhale: Keep hands and elbows in line with shoulders. Feel opening of chest and flattening of upper back, not compression in low back. Keep head forward. Stay firm on back heel.

POSTURE: Ardha Utkaṭāsana.

EMPHASIS: To increase inhalation while increasing demand on musculature. To strengthen legs and upper back.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with feet slightly apart and arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, bending knees, until thighs are parallel to ground and hips are at knee level, bringing chest to thighs and palms to sides of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat, increasing inhalation by 1 or 2 seconds after every 2 repetitions.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Push heels firmly and reach arms forward. On inhale: Lift chest, flattening upper back without exaggerating lumbar curve. Then straighten legs.

5.

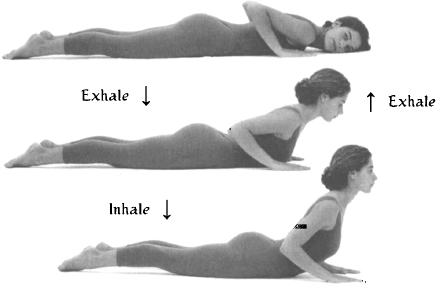

POSTURE: Dhanurāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch and expand chest. To strengthen back and legs. To deepen inhale.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on stomach, resting on forehead, with knees bent and hands grasping ankles.

On inhale: Simultaneously press feet behind you, pull shoulders back, lift chest, and lift knees off ground.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

Increase hold from 2 to 4 to 6 seconds after inhale every second breath.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift head forward, pulling ears away from shoulders. Do not collapse head backward. Keep knees from opening wider than hips.

POSTURE: Ūrdhva Prasārita Pādāsana.

EMPHASIS: To extend spine and flatten it onto floor. To stretch legs.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, legs bent, and knees in toward chest.

On inhale: Raise arms upward all the way to floor behind head and legs upward toward ceiling.

Stay and stretch 2 full breaths.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 4 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Flex feet as legs are raised upward. Slightly bend knees, keeping angle between legs and torso less than ninety degrees. Push low back and sacrum downward. Bring chin down. While staying in position: On exhale, flex knees and elbows slightly; on inhale, extend arms and legs straighter.

7.

POSTURE: Mahāmudrā/Jānu Śirṣāsana.

EMPHASIS: To develop both inhalation and exhalation capacity. To introduce breathing ratio. To strengthen respiratory and spinal musculature.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with right leg folded in, heel to groin, left leg extended forward, and holding left leg between ankle and knee with both hands.

On inhale: Extend spine upward, expanding chest, flattening upper back, and lengthening in front of torso.

Hold after inhale.

On exhale: Maintain posture while pulling belly firmly in.

Hold after exhale.

Remain in extended position 8 breaths. Then sink belly and chest to thigh.

Stay in forward-bended position 4 breaths.

Repeat on other side.

NUMBER: 8 breaths with spine extended; 4 breaths in forward bend, each side.

DETAILS: Ratio: begin with 6-second inhale, 3-second hold, 6-second exhale; 3-second hold. Increase to 8-second inhale, 4-second hold, 8-second exhale, 4-second hold. Bend extended leg so as to focus on spine.

POSTURE: Dvipāda Pītham.

EMPHASIS: To relax back and stretch belly.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, knees bent, and feet on floor, slightly apart and comfortably close to buttocks.

On inhale: Pressing down on feet and keeping chin down, raise pelvis up toward ceiling, until neck is gently flattened on floor, while raising arms overhead to floor behind.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift spine, vertebra by vertebra, from bottom up. On exhale: Unwind spine, coming down vertebra by vertebra.

9.

POSTURE: Śavāsana.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms at sides, palms up, and legs slightly apart. Close eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body. DURATION: Minimum 3 to 5 minutes.

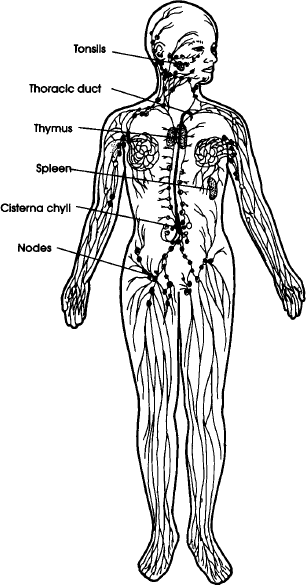

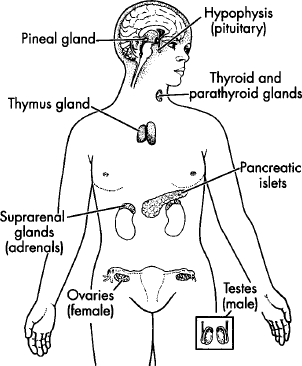

Our cardiovascular system is essential to the life and function of our bodies. Through the bloodstream, nourishment from the digestive system, oxygen from the respiratory system, and hormones from the endocrine system are carried to every cell. Also through the bloodstream, wastes and toxins are collected from the cells and moved toward the body’s main organs of elimination, including the lungs, skin, kidneys, and intestines. In this work, the cardiovascular system is aided by the lymphatic system, whose fluids aid in both absorption of nourishment from the blood and elimination of wastes from the cells.

The cardiovascular system includes the heart, which pumps the blood, the circulating blood itself, and the arteries, veins, and capillaries through which the blood travels. In addition, the heart is encased in a membrane called the pericardium.

The functions of blood are varied and essential to the maintenance of life. In addition to transporting and distributing oxygen and nutrients to the cells and transporting wastes from the cells, blood delivers hormones and enzymes to specific tissues. Through buffers, it also neutralizes acids generated by muscular activity, protects from blood loss by its clotting mechanism, defends against foreign substances through its white blood cells and antibodies, and helps regulate body temperature by appropriate redistribution of heat.

The circulatory system includes a pulmonary circuit, which transports blood to and from the lungs, and a systemic circuit, which transports blood to and from the rest of the body. Arteries carry blood from the heart, veins carry blood to the heart, and capillaries carry blood between the arteries and veins. The chemical and gaseous exchanges that nourish and cleanse the cells taking place across their microscopic walls is a process called diffusion.

The central organ of the cardiovascular system is the heart, a four-chambered pump whose primary role is that of developing the pressure necessary to move a volume of blood through the system at an appropriate speed. The heart is not a continuous pump but works in cycles of contraction (systole) and relaxation (diastole), generating a pressure system that, along with a series of valves, assures that the blood flows in the desired direction.

In a simplified way the process is as follows: Purified, oxygenated blood leaves the lower left chamber (left ventricle) of the heart and travels through the body via the arteries and capillaries, delivering to the cells the materials they need to live and develop. On its journey, the bloodstream also collects wastes, including carbon dioxide, and returns, via the veins, to the heart, entering its upper right chamber (right atrium). From here it is pumped through the lower right chamber (right ventricle) of the heart into the lungs where it is oxygenated and purified of carbon dioxide and other gaseous wastes. And, finally, the blood is pumped back to the upper left chamber (left atrium), of the heart, then into the lower left chamber (left ventricle) and out again through the arteries into the body. This cycle continues from shortly after conception until the moment we die.

Through volume of blood, integrated actions of the heart pump, and changes in the diameters of the blood vessels (vasodilation and vasoconstriction), the cardiovascular system regulates and maintains the body’s entire supply of blood. Because pressure in the system is determined by strength and rate of blood flow, volume of blood in the system, and resistance of the blood vessels, under normal circumstances an increase in heart rate will increase blood flow to the capillaries. The balance between pressure and resistance, which determines our blood pressure, is regulated by both neural (ANS) and hormonal control, which work automatically to regulate our blood flow, ensuring that our cellular need for oxygen and nutrients is met.

However, we also directly influence this complicated system through our thoughts, emotional states, and habitual activities. For instance, just think of how your body responds to emotional stimulation and how thoughts and emotions influence your heart beat. This is because strong emotions like desire, anger, anxiety, and fear speed up the heart and increase blood pressure. This is also why without an increase in physical activity, which engages the muscles to assist the blood flow, excessive cardiovascular response can in time weaken the system.

Our diet influences the volume of fluid in our system. If we have too much salt, for example, we tend to retain fluid (edema), which by increasing the volume of fluid in our body can also raise our blood pressure. If, on the other hand, we are protein deficient, we tend to lose blood volume, which lowers our blood pressure.

Exercise increases the heart rate and, during the period of exercise, tends to raise the blood pressure. If we exercise moderately, resistance in the blood vessels drops (vasodilation), the cells get more oxygen and nutrients, and wastes are more efficiently removed. The end result is a lower resting blood pressure. However, if we exercise excessively, we can actually strain and ultimately weaken our systems. At a certain point our exercise results in fatigue, stress, and, potentially, in strain and injury. In fact, according to the yogis, chronically reaching this point of fatigue by overtraining is one of the causes of disease. It is important to exercise on a regular basis, but we must beware of becoming compulsive and, in the long run, turning our health-oriented program into a stress-producing one!

Conditions that affect the circulatory system are generally grouped under the heading of heart disease. These conditions can be grouped as genetic defects, coronary heart disease, cardiomyopathy, and anemia. Genetic defects include conditions such as irregular heartbeat (cardiac arrhythmia) and heart murmurs. Coronary heart disease involves damage or malfunction of the heart that is caused by the narrowing or blockage of the coronary arteries (arteriosclerosis). Cardiomyopathy refers to diseases of the heart muscle itself such as inflammation of the heart muscle, or enlarged heart. Anemia is a condition of low concentration of oxygen-rich hemoglobin in the blood.

Causes of these conditions can include genetic predisposition, diseases (such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus), infection (myocarditis), elevated blood cholesterol, improper diet and poor digestion, being overweight, poisoning through self-destructive unhealthy habits (such as excessive smoking, drinking, or use of other drugs), tightness of the chest, excessive physical exertion, insufficient physical activity, and chronic emotional stress (including anxiety, anger, and depression).

Symptoms and consequences of these conditions can include rapid heartbeat (tachycardia), chest pain (angina), high blood pressure (hypertension), low blood pressure (hypotension), and finally heart attack (myocardial infarction). Serious heart conditions require the direct care and guidance of a qualified medical practitioner.

When we have heart conditions, we can really help ourselves through the appropriate combination of lifestyle changes and appropriate Yoga practices. We should take time to reflect on our diets, consider giving up smoking or other substance abuses, and regularly take time to relax. If we are overweight, it is important to begin to face this circumstance and work to bring it under control because the heart works overtime when we are chronically overweight. If our lifestyle is sedentary, we can begin a cardiovascular exercise program although, in order to avoid further stress, we should be careful to build up into it gradually.

Although we cannot resolve our heart conditions exclusively through Yoga practice, a well-conceived program of Yoga therapy can be beneficial for restoring and maintaining the balanced functioning of the cardiovascular system.

Hypertension—the technical term for chronically high blood pressure—is a widespread and serious condition, which, if left untreated, can lead to heart attack, stroke, accelerate the development of arteriosclerosis, and even lead to kidney failure. At present, there are effective means to control dangerously high blood pressure through medication. With this control, those who suffer from this condition can begin the process of lifestyle adjustment that can eventually reduce their dependency on medication.

Blood pressure refers to pressure within the arteries during the two phases of the heart cycle. In a blood pressure reading the first number refers to pressure in the arteries when the heart is contracting (systolic) and the second to pressure remaining in the arteries between contractions while the heart is resting (diastolic).

Although both measurements are important, it is the lower number (diastolic) that is the more important indication of hypertension. In fact, many people with high blood pressure don’t even know it unless it is so high that headaches and perhaps chest pains result. Usually we discover high blood pressure when we go to see a doctor or check our own blood pressure at a local mall. In fact, after the mid-thirties, it is a good practice to have your blood pressure checked regularly and, if your diastolic pressure is consistently over ninety, to consult with your physician.

The main orientation for working with hypertension through Yoga therapy is to take a calming and conserving (langhana) approach. We should establish a regular, gentle practice including simple movements coordinated with breathing, adequate rest, simple prānāyāma, palming the eyes, guided relaxation and visualization, and peaceful meditations. I have worked with many people suffering from hypertension. Some have been overweight, and some have been thin. Some have had increased curvature of their upper backs and some have had excessively straight upper backs. Therefore, as high blood pressure is not generally limited to a specific type of person, in working with this condition structural and constitutional needs must be recognized and respected. Accordingly, the following sequence is designed to illustrate universal principles in working with hypertension and further individualization of the practice should be done respecting such needs.

With regards to breathing, we recommend that you avoid the following, at least initially: straining to increase the length of inhale or exhale, prolonging retention of the breath after exhale or inhale, forcing the chest to expand on inhale, and pulling the stomach in strongly on exhale. With regards to postures, we also recommend that you avoid the following, at least initially: strong standing postures, inverted postures, and moving from standing immediately to supine positions.

This particular sequence was developed for D.M., a forty-five-year-old caretaker of the gardens of a large estate, who came to see me for help with his hypertension. He was referred to me by a physician who believed that D.M. would benefit from our work. I saw D.M. two times per week for two weeks, and then once a week over the next several months. This sequence evolved out of our work together over the first month. When we began our work together, D.M. told me that he was on medication and that he was curious to see what Yoga could do for him. Although he was physically active in his profession, he told me that he was not involved in any regular exercise program. He complained of chronic low back tension and discomfort.

We began our work together with very simple arm movements and breathing exercises, done seated in a chair. He was surprised to discover how tight his back was and how shallow his breathing.

As we got to know each other, he began to share with me more about his life. He had been living for about three years with a woman who had a daughter from a previous marriage. It seems that he and the daughter, who was just going through puberty, were not getting along. This was creating problems between him and his girlfriend, and the tension was high in the house. I could see he was both frustrated and angry and was developing resentment toward the daughter. I asked him about his work, and he told me that he spent a lot of time running a lawn mower and a Weed Eater™. Both machines have intense vibration and high-pitched sounds.

As he became more comfortable with the exercises, I added progressive lengthening of exhalation to his practice, and later some low-pitched humming sounds to help him to relax. I also introduced some postures to help strengthen and loosen his back. I strongly suggested that he avoid running the machines when he was angry and that he use ear protection to dull the sound.

In subsequent months, he told me that he had hired someone to work with him and run his machines. He also told me that he and his girlfriend and her daughter had begun family counseling. Things were much better between him and the daughter, and he and his girlfriend were planning to get married.

When I asked him about his back, he told me that he had forgotten about his back problems. He was happy to report that his doctor had reduced his medication. He was feeling much better about himself and his prospects for the future.

1.

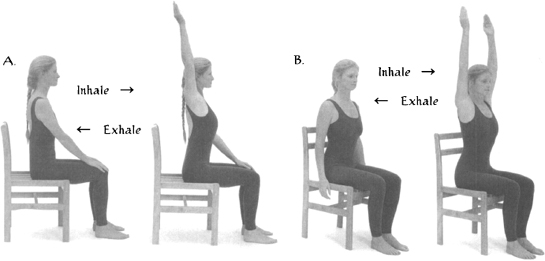

POSTURE: Arm movements in chair.

EMPHASIS: To gently mobilize rib cage while deepening inhale and exhale.

TECHNIQUE:

A: Sit on a chair or bench with back straight and hands on knees.

On inhale: Raise one arm forward and up over head.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

Repeat on other side.

B: On inhale: sweep both arms out to sides and up over head.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: A four times each side, alternately. Rest.

Then B six times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly and lift chin slightly.

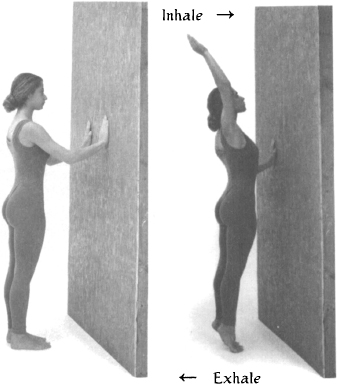

POSTURE: Uttānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To extend length of exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with feet slightly apart facing a chair.

On inhale: Raise arms forward and up over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, bending knees slightly, bringing chest to thighs, and palms to chair.

On inhale: Return to previous position with arms over head.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back. Keep knees bent until end of movement.

3.

POSTURE: Sitting on chair.

EMPHASIS: To relax using sound and deep breathing.

TECHNIQUE:

Inhale deeply.

Long exhale, using a soft, low-pitched humming sound on every other exhalation.

NUMBER: 16 breaths.

POSTURE: Cakravākāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch rib cage on inhale. To gently compress and stretch belly on exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Get down on hands and knees, with shoulders vertically above wrists and with hips above knees.

On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly.

On exhale: Gently contract belly, round low back, and bring chest toward thighs.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lead with chest, keeping chin slightly down. Avoid compressing low back; rather, feel chest expanding. On exhale: Round low back without collapsing chest over belly. Avoid increasing curvature of upper back. Let chest lower toward thighs sooner than hips toward heels.

5.

POSTURE: Bhuja gāsana.

gāsana.

EMPHASIS: To gently stretch and expand rib cage, deepening inhalation.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on belly with palms by chest, head turned to one side.

On inhale: Lift chest, turning head to center.

On exhale: Lower chest to floor, turning head to opposite side.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Use back to lift chest; don’t push with arms.

POSTURE: Apānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To gently compress belly while progressively extending exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with both knees bent toward chest and feet off floor. Place each hand on its respective knee.

On exhale: Pull thighs gently but progressively toward chest.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 12 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Pull gently with arms, keeping shoulders relaxed and on floor. Press low back down into floor and drop chin slightly toward throat. Progressively lengthen exhale with each successive repetition.

7.

POSTURE: Śsavāsana with support.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms at sides, palms up, and legs slightly apart. Close eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body.

DURATION: Minimum 3 to 5 minutes.

Hypotension is generally not considered to be as serious as hypertension, yet many people suffer from it; and serious low blood pressure can result in oxygen and nutrient deprivation in the peripheral systems. Because low blood pressure is often related to overall weakness in the system and specifically weakness of the digestive fire, it is often accompanied by lack of energy, poor circulation, coldness in the extremities, weakness of the heart muscle, and a tendency toward dizziness. Once I was in India working with a woman who had finished her practice and was resting on the floor when someone knocked on the door. She got up to a standing position suddenly, and the next thing I knew she had passed out on the floor. So, a general principle for working with hypotension is gradual transitions, particularly from a lying to a standing position. For the same reason, standing postures with the head below the waist often result in dizziness.

As with hypertension, in cases of hypotension the same principle of respecting structural differences applies. I have worked with heavyset and thin people with low blood pressure. For some, shoulder stand presents too much risk to their necks and upper back; for others shoulder stand is a wonderful posture. Therefore we recommend twisting, backward bending, shoulder stand, and some holding of the breath after inhalation, and the following sequence is illustrative of our approach and how each practice can be adapted, respecting the principles given earlier in this book, to your own unique structural needs.

This particular sequence was developed for D.O., a thirty-eight-year-old woman who came to me without any particular complaints. She began by coming to group classes sporadically over several years. She would appear for a while and then disappear again. D.O.’s body was very flexible, and she was easily able to practice many āsanas. She always wanted to do the shoulder stand and if I didn’t include it in the sequence, I would invariably find her doing it on her own at the end of the class.

After one period of absence, she came to me after class and expressed interest in seeing me privately. D.O. told me that her main interest was in spiritual matters, but that she was coming to Yoga only to help maintain her body and support her health. She told me that she was living off of a small inheritance, which kept her at a minimalist lifestyle, but that she didn’t have to work. She was very much the “loner,” though she went to church regularly, and I never knew her to have a boyfriend.

As we began working together privately, I noticed that although she was interested and willing to work her body, she had great resistance to working with her breath. When I commented on that, she said that focusing on her breath made her dizzy. She told me she often felt dizzy when getting out of bed in the morning. She also said that she often felt weak and without energy reserves. I asked her about her diet, and she told me that she was practically a “fruitarian.”

Since she had worked with me in group classes on and off for several years, she was very familiar with our approach to āsana practice. Over several months, we evolved the following course, which I asked her to practice in the afternoon. I suggested that she go for a brisk walk in the morning, preferably with some hills to climb. I also asked to her to eat some oatmeal in the morning before her walk. At one point, I encouraged her to find some kind of work or social service to engage more actively in the community.

D.O. still shows up at group classes sporadically, but assures me she is practicing on her own. She told me that she now enjoys the small breathing exercises I gave her and no longer gets dizzy when she practices. She also happily told me that although she still wasn’t working, she had begun to go to church gatherings and had met a man, and that they had recently moved in together.

1.

POSTURE: Dvipāda Pīṭham.

EMPHASIS: To warm up body by engaging large muscles of thighs and buttocks.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, knees bent, and feet on floor, slightly apart and comfortably close to buttocks.

On inhale: Pressing down on feet and keeping chin down, raise pelvis until neck is gently flattened on floor, while raising arms overhead to floor behind.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift spine, vertebra by vertebra, from bottom up. On exhale: Unwind spine, coming down vertebra by vertebra.

2.

POSTURE: Cakravākāsana.

EMPHASIS: To make transition from supine to standing position. To stretch rib cage on inhale and low back on exhale.

TECHNIQUE: Get down on hands and knees, with shoulders vertically above wrists and with hips above knees.

On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly.

On exhale: Gently contract belly, round low back, and bring chest toward thighs.