Chapter 5

Chapter 5

As we have seen, the key to using Yoga practice as therapy lies in our ability to link our conscious minds to the unconscious rhythms of our bodies. This being the case, an understanding of exactly how the body, mind, and emotions interact is essential to the study of Yoga.

From the standpoint of Yoga theory, mind and body always function as one organic whole. Intellectual and emotional processes are regarded in much the same way as physiological and structural ones—as material processes. In fact, according to this view, all manifested forms are simply differentiations of a single universal material substance (prakrti). These differentiations extend from the grossest external objects, such as rocks and trees, to the subtlest internal objects, such as our changing emotional states and our self-image.

On the other hand, Yoga theory does makes an important distinction between this perpetually changing substance, which it calls the “seen,” and pure, changeless, undifferentiated consciousness (purusa), which it calls the “seer.” In fact, it views identification with the ever-changing differentiations of substance, from the grossest to the subtlest, as the result of misapprehension (avidyā), which, in turn, is the cause of suffering. The practice of Yoga involves two goals: the removal of the misapprehension that results in the qualities of mind that perpetuate emotional drama (through the process known as viyoga); and the awakening of the discrimination (viveka) that results in those qualities of mind that enable us to reach our highest potential (through the process known as sa yoga).

yoga).

Many years ago, while watching a program on PBS concerning the process of getting the spaceship Voyager out of this solar system, I was struck by the analogy between the goal and challenges of that mission and those of any individual who wishes to overcome suffering and achieve his or her highest potential.

The problem for the rocket scientists was to figure out a way for the spaceship to gain enough momentum to escape the solar system. They realized that they could use the gravity of each planet to pick up sufficient momentum to propel the spaceship outward from the sun and, ultimately, beyond the gravitational pull of the solar system. The challenge was to program the spaceship with the correct velocity and angles of approach to the planets along the way in order to avoid crashing into them or getting stuck in orbit around them. Miscalculating the approach in one way would cause the spaceship to crash and burn in the gravity well of that planet. Miscalculating the approach in another way would cause it go into permanent orbit. However, if the approach were just right, the spaceship would receive a boost from each planet along the way that would enable it to ultimately achieve escape velocity and would propel it beyond the solar system. In much the same way, we can learn to break through the limitations of our own personal solar systems, which include all the particular circumstances of our personal lives. We can learn to avoid crashing into or revolving around our personality and, like the spaceship, use the “gravitational forces” within our own systems to achieve escape velocity and propel ourselves beyond the limitations of our conditioning and onward into new dimensions of our personal evolution.

In his famous commentary on Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtras, Vyāsa describes five possible levels or states of mind, as follows:

Kṣipta: A seriously disturbed, heavily distracted, and discontinuous state of mind.

Mūdha: A seriously depressed mind, covered in darkness and without hope.

Viksipta: The “normal neurotic” mind, which alternates between distraction and attention.

Ekāgra: A mind that is focused and undistracted in one-pointed concentration.

Nirodha: The highest potential of mind. It is a state of mind that is freed from conditioned response and, therefore, allows the “seer” to perceive without distortion.

At the first three levels of mental development, we are likely to be so self-absorbed that we either crash into the gravity well of our own personality or go into permanent orbit around ourselves. Another possibility, at these levels of mental development, is that we become magnetically attracted to some other “gravitational center” (such as a lover, community, or guru) and are either absorbed into its mass or locked into orbit around it. In fact, crashing and/or orbiting are inevitable at these three levels of mental development because we have not yet programmed ourselves to use the “gravitationally attractive bodies” within our personal systems to help us reach “escape velocity.” At the level of ekāgra, we have the capacity to commit to and sustain a personal practice that will enable us to recognize the trap of revolving around the conditioned mind and to continue our journey of personal evolution. And, finally, in the state of nirodha, we begin to function at the level of our highest potential as human beings.

The nature of the seer and the process of spiritual development is not the focus here and must wait for a full consideration in our next work. However, some sense of the distinction between seer and seen is important to a correct understanding of the link between our minds (including all of our intellectual and emotional activity) and our bodies (including all of our physiology and anatomy). And the ability to make this distinction is especially important if we are to avoid the mistake of identifying the seer with those subtle functions of the complex brain, which we will now describe, that are part of the seen.

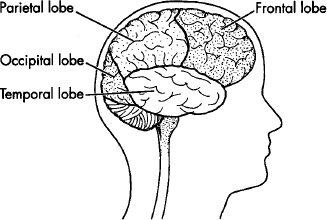

For the sake of simplicity in considering this link between mind and body, we will divide the brain into three main parts:

1. The brain stem and cerebellum are involved in the mechanical, and usually unconscious, processes of regulating and processing the sensory, emotional, autonomic, hormonal, and motor functions of the body.

2. The cerebrum is involved in conscious processes such as intellectual thought, the processing and comprehension of sensory input, the coordination of voluntary motor commands, and the storing and processing of long-term memory as well as conscious sensory and motor memory.

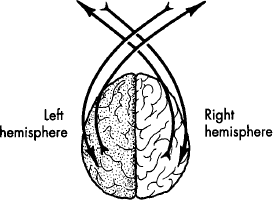

The cerebrum is divided into two hemispheres, each having four lobes (frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal). Each hemisphere receives ascending sensory input from and generates descending motor commands to the opposite side of the body, so that the right hemisphere controls the left side of the body and the left hemisphere controls the right. In addition, each lobe contains functional regions associated with the conscious perception of specific sensory information (in the form of touch, sight, sound, smell, and taste) and motor commands (including voluntary control of the skeletal muscles).

The prefrontal lobe of the cerebrum coordinates and analyzes the vast quantity of data received from the senses, and under normal circumstances dictates our responses and contains the perspective we have of ourselves and the external world that surrounds us.

3. The limbic system is specifically concerned with learning, memory, and with the emotions and their related behavioral drives. But, of even more importance to our consideration of Yoga therapy, the limbic system provides the link between the conscious, intellectual functions of the brain and the unconscious, mechanical functions of the body.

Structurally, the limbic system is located on the border between the seat of conscious functioning (the cerebrum) and the seat of unconscious functioning (the brain stem and cerebellum). One part of the limbic brain (including hippocampus and amygdala) connects directly to the cerebrum; the other part (including thalamus and hypothalamus) connects directly to the brain stem and cerebellum.

Brain functions associated with the hippocampus, the amygdala, and their connection to the cerebrum appear to be as follows: The hippocampus imprints and subsequently retrieves memory concerned with information. The amygdala imprints and subsequently retrieves memory concerned with emotion, and, in turn, it controls and triggers emotional response. Via the circuit created by the connection between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex of the cerebrum, thought and emotion are linked. And, via certain direct-circuit links between the amygdala and thalamus, in certain cases, emotional response is directly triggered by sensory input, bypassing the cerebrum and, therefore, avoiding processing by the conscious mind altogether.*

Brain functions associated with the thalamus, the hypothalamus, and their connection with the cerebellum appear to be as follows: The thalamus receives ascending sensory information on its way to processing in the appropriate area of the cerebral cortex. The hypothalamus processes information concerning changing emotional states and related behavioral drives. Through its connection to the brain stem, the hypothalamus directly links the changing emotional states to the nervous and endocrine systems, which, in turn, control and regulate the other organic processes of the body. And, as a result of this connection, imbalances in other systems of the body can also effect hypothalamic activity, producing strong emotion and influencing thought.

Our understanding of the structure and function of the limbic brain continues to grow as neuroscientists become progressively more sophisticated in mapping brain circuitry, and particularly in mapping the pathways of emotional response within the brain. However, we now know for certain that all sensory input (including externally related seeing, hearing, touching, tasting, and smelling, and internally related sensations of the visceral and other internal bodily parts) passes through the limbic brain on its way to the cerebrum for analysis, and back again through the limbic brain, where appropriate responses are regulated via the hypothalamus. It is now clear to neuroscientists that all parts of the brain and nervous system are connected to and converge in the limbic brain.**

The bodily response to stress initiated in the hypothalamus, known as the fight-or-flight response, involves a chain reaction of chemicals released into the bloodstream, as follows: corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is released from the hypothalamus; CRF then triggers the release of adrenocorticotropin hormone (ATCH) from the pituitary gland; and, finally, ATCH triggers the release of adrenaline and Cortisol from the adrenal glands. The results of this chain reaction are an increase in alertness, muscle tone, heart rate, and blood pressure; a heightening of all sensory reflexes; a deepening of respiration; an increase in the peripheral circulation of blood to the skeletal muscles, as digestion stops and the flow of blood is directed away from the stomach and intestines; a release of red blood cells from the spleen into the bloodstream in order to help supply increased oxygen to the muscles and to aid in the removal of residual carbon dioxide; and a whole range of other complex bodily changes.

Through this mechanism, the body is able to cope with stress and, therefore, to survive. However, if, through chronic physical and/or mental stress, this mechanism is habitually engaged, the result is a depression of the immune response and a weakening of the entire system.* In each of us there exists a unique set of triggering devices, related to how we perceive any given situation. This explains why people respond differently to the same situation because, as Patañjali points out, each of us comes to our experiences with a different set of memories and associations. Depending on those particular memories and associations, any experience can elicit a whole range of emotion—from pleasure to fear. For example, I remember being relaxed and comfortable one night while walking in a dark and quiet but familiar wooded area with a friend from the city, who, unlike myself, was extremely anxious at being in an unfamiliar place and away from the lights and sounds to which he was accustomed. But, whether the source of stress is internal, external, psychological, physical, or some combination of these factors (which is usually the case), it is clear that the link between conscious mind and unconscious body responses work in both directions. On the one hand, cerebral activity can directly trigger emotional response, and emotion can stimulate response in the autonomic system. On the other hand, changes in our physiology—due, for example, to hormonal cycles, illness, toxicity, or drugs—can trigger emotional responses that, in turn, influence thought.

Recognition of this fact has led to the development of the relatively new field of psychoneuroimmunology, which studies the links between mind (including thought and emotion), physiology (beginning with the nervous and endocrine systems), and the immune system. The results of the research carried out in this field point to a strong link between state of mind (including habits of thought and emotional response) and physical health; and there is mounting evidence to suggest that people who remain in chronic states of stress and emotional disturbance have a significantly higher incidence of disease, including digestive, respiratory, and cardiovascular.

With the development of new fields such as psychoneuroimmunology, modern science is beginning to confirm what the ancient yogis have recognized for thousands of years: disturbing emotions play a primary role in disease; and, therefore, emotional health is fundamental to the maintenance of health in the physical body. According to Yoga theory, the objects of the senses are like food: the right kind of sensory stimulus is nourishing; the wrong kind is toxic. When the end result of the complex interactions we have been exploring are pleasing sensations, there is a calming and nourishing effect on body, emotion, and thought; when they are unpleasant, there is a sense of disruption. For example, a singing bird or a gently murmuring stream is usually relaxing and restorative, while a violently vibrating jackhammer or excessively loud music often produces anxiety and stress.

The ancient masters developed complete sciences, related to the senses, to help correct imbalances and nourish our systems. For example, the Āyurvedic culinary arts relating to the sense of taste, aromatherapy relating to the sense of smell, color therapy relating to the sense of sight, and traditions of chanting and music relating to the sense of hearing. In addition, the ancient masters recognized the following negative attitudes as particularly overwhelming and tending toward dysfunctional behavior:

Kama: obsessive desire, lust

Krodha: anger, hostility

Lobha: greed, possessiveness

Moha: delusion, self-deception

Matsarya: jealousy, resentment

Mada: arrogance

Bhaya: fear, anxiety

According to the teaching of Krishnamacharya, all these negative emotions stem from the two root attitudes of aha (“I am the doer”) and mama (“it is for me”); and only when the attitude becomes that of namama (“not by or for me”) do negative emotions cease to arise. In other words, in terms of our Voyager analogy, until we can stop revolving in endless circles of emotional drama and misapprehension around the limiting self-concepts of the conditioned mind, we remain either crashed into or trapped within the narrow confines of the little “me” and, therefore, are fundamentally unable to achieve our own higher potential.

(“I am the doer”) and mama (“it is for me”); and only when the attitude becomes that of namama (“not by or for me”) do negative emotions cease to arise. In other words, in terms of our Voyager analogy, until we can stop revolving in endless circles of emotional drama and misapprehension around the limiting self-concepts of the conditioned mind, we remain either crashed into or trapped within the narrow confines of the little “me” and, therefore, are fundamentally unable to achieve our own higher potential.

To counteract these attitudes and the limitations they impose, the ancient yogis also taught the importance of śraddhā (faith), and where śraddhā was not present, they stressed the value of association with good people (sat sangha) and the cultivation of right attitudes, including friendliness toward those who are happy, compassion toward those who are suffering, joy in relation to good actions of others, and equanimity in relation to wrong actions of others.

But most important, on the basis of their understanding of the interconnectedness of all things, they developed the art and science of affecting overall change in our system through the various techniques of Yoga, including āsana, prānāyāma, chanting, and meditation. Understanding the direct influence of habits of thought and emotion on biochemistry, and knowing that positive states have a deeply restorative impact on the entire system, they were able to develop certain practices to transform negative qualities of mind and to promote general well-being as a basis for spiritual development.

The effectiveness of the technology they developed has been repeatedly demonstrated by scientific studies. For example, in states of deep meditation, the heart and respiratory rates consistently slow down; the overall metabolic rate drops; as the metabolic rate drops, muscular tension decreases and blood flow increases to the muscles; and the result is a positive influence on biochemistry and an improvement in the overall condition of health—all of which strongly suggests that by changing our state of mind, we can affect an overall qualitative change in our lives.*

According to theories in neuroscience, the evolutionary origin of the limbic system is linked to the sense of smell and can be traced to that part of the limbic brain known as the olfactory lobe.** It is primarily through the sense of smell that animals identify danger, food, or sexual partners; and it was from the olfactory lobe, in its most primitive form, that reflexive messages were sent to the rest of the nervous system, initiating appropriate behavioral responses. The limbic system still forms the “emotional core” of our own vastly more complex brains and, as we have seen, still has the capacity to powerfully influence and even override the rationality of the cerebral cortex.***

The ancient masters specifically developed the practice of prānāyāma (regulation of the breath) to balance the emotions, clarify the mental processes, and ultimately to integrate them into one effectively functioning whole. In light of what we now know about the close connections between the various structures of the limbic brain and the prefrontal lobes of the cerebral cortex, it is interesting to speculate about exactly what the ancients actually did understand concerning the power of prānāyāma.

Though a full treatment of the complex and highly evolved science of prānāyāma is beyond the scope of this work, it is interesting to note that the practice of prānāyāma has a significant impact on the olfactory lobe and, in this way, on the limbic brain. In fact, the ancient masters taught that states of physical and emotional arousal or nonarousal can be regulated via control of the breath at the nostrils. Specifically: inhaling through the right nostril and exhaling through the left (sūrya bhedana) is said to activate or stimulate our system; and inhaling through the left nostril and exhaling through the right (candra bhedana) is said to calm, soothe, and pacify our system. We can also use both inhalation (brahmana) and exhalation (langhana) techniques to stimulate or soothe our systems respectively; and we use different ratios between the various parts of the breathing cycle—i.e., between inhale, retention after inhale, exhale, and suspension of the breath after exhale—to achieve very specific degrees and types of stimulation and pacification. A detailed exploration of this fascinating and profound science will be the topic of a later work.

One thing is certain: the ancient masters knew how to use prānāyāma techniques to “remove that which covers the light of the mind” (YS, 2:52). In other words, they knew the power of prānāyāma to balance and clarify the emotions so that they support rather than obstruct the unfolding of our highest potential.

Although the whole question of mental illness is very complex and is not our focus here, the following generally recognized conditions of mental aberration are suggestive of the types of problems and range of effects that are often involved:

Neuroses: a wide range of psychological and behavioral responses whose common denominator is anxiety. These vary in seriousness and can impair both work, social adjustment, and health.

Schizophrenia: a psychosis marked by progressive withdrawal from reality, grossly inappropriate behavior, aberrations of thought, discrepancies between thought content and mood, delusions or hallucinations, et cetera.

Depression: varies from normal reactions to the sorrows of life to serious mood disturbance that can lead even to suicide. Full-blown depression involves weight loss, decreased sexual desire, difficulty sleeping, excessive fatigue, chronic pain or complaints about pain, headaches, a sense of worthlessness, and difficulty concentrating.

Many times conditions of mental and emotional illness have their basis in brain chemistry. When this is the case, the problem is often related to an abnormal concentration of neurotransmitters—the chemicals that trigger and block impulses concerned with the flow and regulation of motor and sensory input to the brain and, therefore, that regulate the nervous system. Other biological causes include the following: certain disorders of the nervous, endocrine, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems; infectious diseases; use of drugs (whether illicit, over-the-counter, or prescription); poor dietary habits; and environmental toxicity and other environmental factors.

A psychiatrist once told me that if a troubling emotional condition is psychologically based, then the appropriate treatment is one of several of a variety of psychotherapeutic technologies; but if that condition is biochemically based, though psychotherapeutic technologies may be helpful, the most appropriate treatment is pharmacological. Our point of view is that the integrative approach of Yoga therapy, working at the level of the body, breath, and mind through the practice of āsana, prānāyāma, and meditation, is very effective as an adjunct to any treatment plan. In fact, science has demonstrated the effectiveness of meditation in this regard, and while prānāyāma has received little attention from science, we have seen again and again its power with disturbed people to help balance emotion and even to reduce dependence on psychiatric medication.

Although a well-conceived Yoga therapy practice may be helpful in any condition, where there is genetically or disease-based biochemical abnormality, we recommend seeking professional psychiatric or medical care. In this section on emotional health, we are primarily addressing the vast majority of “normally neurotic” people, who have minor to serious emotional imbalance, and for whom Yoga therapy can function as a temporary method of symptom reduction so that they can begin the work of permanently removing the cause of their problems. The ancient teachings on this deeper work have been given to us by Patañjali, in the science of Kriya Yoga, which we will explore in detail in our next book.

According to Yoga theory, our emotional condition fluctuates between states of balance, excess, and deficiency. The ancient yogis explained these states as a result of the predominance of one of the three primary energies (gunas) that are the fundamental constituents of the universal material substance (prakrti) that makes up the world of the “seen”: sattvic (balanced), rajasic (excessive), and tamasic (deficient). And they developed a highly evolved science around these states in relationship to health and disease.

The sattva guna can be characterized as an energy of balance, harmony, and equilibrium. When it is predominant, and all of the systems of our body and mind are in balance, there is an optimal level of mental clarity, physical health, emotional serenity, and creative inspiration. The sattvic quality of mind can be described as a neutral state of relaxed present awareness; it is described in the Yoga tradition as luminous and clear, and it represents one of the most important goals of Yoga practice.

The attitudes and emotions considered to be sattvic include appreciation, awe, bliss, compassion, contentment, courage, forgiveness, friendliness, goodness, happiness, honesty, joy, kindness, love, patience, peace, serenity, stability, tenderness, tolerance, and wonder. In fact, the emotions of happiness and joy have been scientifically demonstrated to increase the presence of white blood cells and the levels of the antibody immunoglobulin A (IgA), both of which are fundamental to the immune response.*

The rajo guna can be characterized as an energy of activity and creativity. When it predominates, however, it may lead to hyperactive, aggressive behavior, and an inability to control energy in difficult and unpleasant situations. The rajasic quality of mind can be described as a state of agitation. Because unbalanced rajasic energy can lead to violence and other extreme actions that cause suffering both to ourselves and others, it is important to know how to rectify an unbalanced rajasic condition.

Anger can be considered an example of a rajasic emotion. There are many different degrees and kinds of anger, ranging from quiet brooding anger to explosive rage and even violence. The following attitudes and emotions can be included under the general heading of anger: animosity, annoyance, aversion, criticism, cruelty, enmity, hostility, hatred, impatience, indignation, irritation, rage, resentment, violence, and wrath. In any form, strong states of anger trigger the fight-or-flight response, providing the body with a chemical rush that readies it for appropriate or inappropriate response to a given situation.

Anger is impulsive; it leads to a short reaction threshold; and it too often has negative effects on our relationships and on our health. Studies show that heart disease is the direct result of chronic states of anger and hostility; that such states are particularly dangerous for those who already suffer from heart disease; and that anger and hostility represent a particular risk to men. They also show that anger depresses the levels of the antibody immunoglobulin A (IgA), which is fundamental to the immune response.*

Once we recognize that we are in a state of anger, it is possible to defuse it. One way is to use a langhana prānāyāma practice to regulate the breathing. For example, by sitting down and focusing on where the breathing starts and where it ends, and by practicing a long exhale and short suspension of the breath after exhale for some time, the tendency to impulsive reaction will be reduced. Because this is a technique to manage, and not suppress emotion, apply the technique and notice what actually happens in your system. Generally, the efftect of this technique will be soothing. Finally, when the anger has subsided, continue using the breathing technique while reflecting on and reevaluating the situation that led to your anger. Because this is a pratipakṣa technique (what modern psychology knows as “cognitive reframing”) and, therefore, involves reconditioning, once the reaction is over and has been restructured in your mind, your initial anger may even look silly to you.

Anxiety is another rajasic emotion. There are many different degrees and kinds of anxiety, ranging from chronic, mild worry to obsessive-compulsive disorder to full-blown panic attack. The following attitudes and emotions can be included under the general heading of anxiety: agitation, apprehension, compulsiveness, concern, dread, edginess, fear, horror, insecurity, nervousness, obsessiveness, panic, paranoia, phobia, surprise, terror, uneasiness, wariness, and worry. In any form, strong states of anxiety, like strong states of anger, trigger the fight-or-flight response and can manifest symptoms of sweating, accelerated heart beat, tightness in the belly, muscle tension, shakiness of the limbs, inability to be still or to concentrate, shortness of breath, and insomnia. Increased muscle tension and decreased circulation to the areas of tension are the result of pressure on the capillaries, which together cause an increase in lactic acid.* Lactic acid, in turn, causes muscle fatigue, a tendency toward muscle cramping, and an increase in stress to the liver. Extensive research conclusively links states of anxiety to depressed immune function; to increased susceptibility to gastrointestinal problems, such as IBD and IBS; to infectious disease, such as colds and flus; to respiratory conditions, such as asthma; to the onset of type I and type II diabetes; and even to the metastasis of cancer. Although evidence supports a link between anger and hostility and heart disease in men, in women heart disease is more strongly linked to states of fear and anxiety. There is also evidence suggesting that in many cases anxiety has a genetic component and/or is based in biochemical imbalance.**

In practice, we must make a distinction between normal tension and anxiety and those pathological conditions that reflect a biological disorder rather than a psychological one. For example, where there are serious and persistent conditions of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic attacks, or post-traumatic stress disorder, it is best to seek professional psychiatric help.

One way to reduce anxiety is to use a brahmana/ langhana strategy to reduce the hyperarousal in the mind and the subsequent stress in the body. First create a level of physical activity equal to the level of bodily stimulation generated by mental anxiety. Once the muscular and respiratory activity has reached a sufficient level, gradually slow the movement down and introduce deep, slow breathing. We also recommend the use of sound techniques to help shift attention away from anxiety-producing thoughts; and, after that, we recommend either meditation or prayer, depending on one’s inclination.

In addition, the support, caring, and touch of loved ones is an invaluable remedy to any condition in which the rajo guna is predominant. Finally, in these conditions, we suggest avoiding alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine; we recommend spending time in nature; and, if there is little sunlight, we also recommend sitting in front of a full-spectrum light box for at least twenty minutes each day.

Conditions of anxiety are as variable as the people who suffer from them, and, as we have seen, a Yoga therapy practice is ideally adapted to the uniqueness of each individual. The sequence that follows offers an example of working with conditions of chronic anxiety and, though not prescriptive, is indicative of an approach to these conditions.

C.S. was a forty-year-old artist when she first came to our school to study Yoga many years ago. She had been married for a long time, though she had no children. She attended group classes consistently for several years. C.S. was always attentive to the needs of others in the class and had a quality of kindness that was felt and appreciated by all. She was soft spoken and somewhat self-effacing.

I was very surprised, one day, when she told me in private that she could no longer come to class. She had a strange expression on her face and told me in a quiet voice that she couldn’t take it anymore. I had no idea what she was talking about. Then it began to come out that she felt that the other members of the class had a bad opinion of her, and that they talked about her behind her back. Fortunately she did not include me in this group. She told me that I must be aware of how the conversation in the room shifted when she arrived, and how the other people looked at each other with little, knowing smiles.

I asked C.S. if she was interested to continue her studies with me in private, and she said yes. She came to see me once a week for nearly a year. Over time, it came out that she had been in a group of artists many years earlier and finally had to leave for the same reasons. I assured her that everybody in this group had a very high opinion of her, and she had their love and respect. Her initial reaction was almost a bit angry, and she couldn’t understand why I was hiding the truth from her. So for many months we simply dropped the discussion and focused on her personal practice.

Over the years, she had never complained of discomfort in her body. She did occasionally complain that her breath was shallow and that she had trouble sleeping. Though she didn’t experience pain in her body, she was not strong. And she lacked confidence in herself. She told me that she had difficulty being around large groups of people and that she preferred being alone. C.S. confessed that she couldn’t go out to the market without anxiety about what other people were thinking and saying to each other about her. She also told me that she had reached an impasse in her work ad had not been able to get beyond it.

My initial strategy included a brahmana āsana practice to strengthen her body and deepen her breathing capacity, and a langhana prānāyāma practice to help balance and stabilize her emotional state. I hoped that strengthening her body would also help increase her self-confidence.

C.S. lived in a valley that bordered on state forest. Near her house were paths that led up into the mountains. We developed the following practice, which I asked her to do in the early morning, followed by a brisk hike in the forest before beginning her day.

In my conversations with C.S., I learned that she had a strong and positive memory of her deceased grandmother—who had been a devout Catholic. One day she told me that she had a dream in which she was a little girl and was with her grandmother, who was reading to her. I asked her if she remembered what her grandmother was reading, and she said it was her grandmother’s favorite psalm.

I asked C.S. to bring her Bible to her next class, and we read the psalm together. It was the famous Psalm 23, which begins “The Lord is my shepard, I shall not want.” In the middle of the psalm is the line “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me.” We decided to integrate that psalm into her practice. I asked C.S. to read the psalm before each practice and, so she could feel as if she were not alone, to use the words “thou art with me” as a mantra to count certain parts of her breath throughout the practice. She told me how this added element took her practice much deeper, and how much it meant to her.

I left my home in Hawaii to work in the continental United States and in Europe for about four months. While I was away, she practiced the sequence that follows. One evening, after returning home, C.S., whom I had not seen for about five months, arrived for a group class. It was the same class that she used to attend, and many of the friends were very happy to see her. After class, she told me that she had taken a job in an art gallery and, through some connections there, had got a big commission for her own artwork. She told me that she was feeling stronger and more confident, and happy to be back in class.

1.

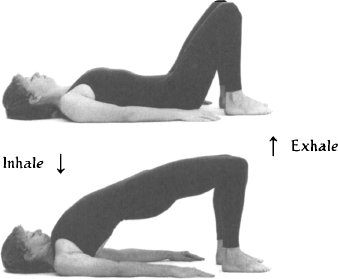

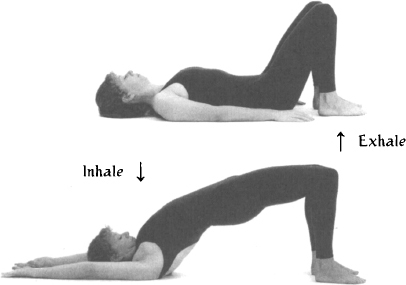

POSTURE: Dvipāda Pitham.

EMPHASIS: To warm up the body by engaging thighs and buttocks.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, knees bent, and feet on floor, slightly apart and comfortably close to buttocks.

On inhale: Pressing down on feet and keeping chin down, raise pelvis until neck is gently flattened on floor.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift spine, vertebra by vertebra, from bottom up. On exhale: Unwind spine, coming down vertebra by vertebra.

2.

POSTURE: Vajrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To make transition from supine to standing. To stretch low back.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, sweeping arms behind back, bringing hands to sacrum with palms up.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Bring chest to thighs before buttocks to heels. Rotate arms so palms are up and hands rest on sacrum. On inhale: Expand chest and lift it up off knees as arms sweep wide.

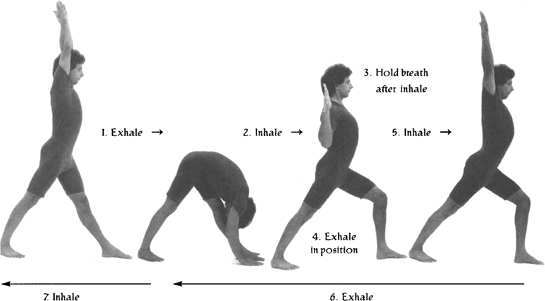

POSTURE: Vīrabhadrāsana.

EMPHASIS: To build energy, strengthen muscles of back, expand chest and flatten upper back, increase hold after inhalation, and strengthen leg muscles.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with left foot forward, feet as wide as hips, and arms at sides.

On inhale: Simultaneously, bend left knee, displace chest slightly forward and hips slightly backward, and bring arms out to sides and shoulders back.

On hold after inhale: Mentally recite thou art with me.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times each side.

DETAILS: On inhale: Keep hands and elbows in line with shoulders. Feel opening of chest and flattening of upper back, not compression in low back. Keep head forward. Stay firm on back heel. On hold after inhale: Recite mantra twice for the first two repetitions, three times for the second two repetitions, and four times for the last two repetitions.

4.

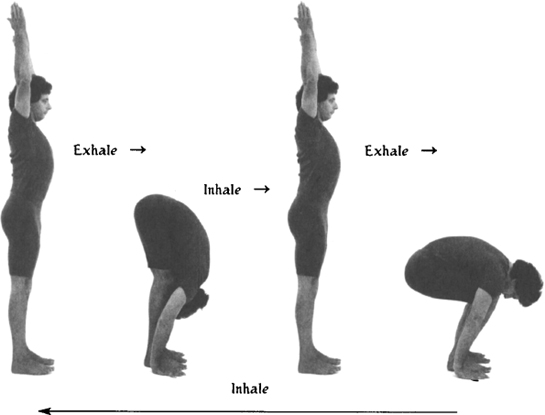

POSTURE: Uttānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To compress belly and lengthen exhalation.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with feet slightly apart, arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, bending knees slightly, bringing chest to thighs, and palms to sides of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Make exhalation progressively longer with each repetition. Bend knees to facilitate stretching of low back. Move chin down toward throat. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back. Keep knees bent until end of movement.

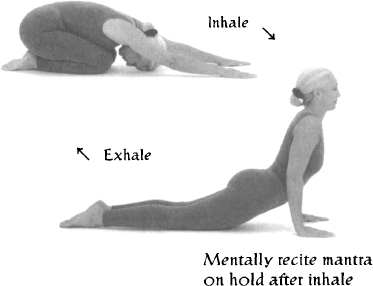

POSTURE: Vajrāsana/Ūrdhva Mukha Śvānāsana combination.

EMPHASIS: To energize system by engaging musculature of upper body, expanding chest, and stretching belly.

TECHNIQUE: From a kneeling forward bend position, place hands on ground in front of body.

On inhale: Stretch body forward and arch back, keeping only hands and from knees to feet on floor.

On hold after inhale: Mentally recite thou art with me.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Expand chest, stretch belly, and avoid compressing low back. On hold after inhale: Mentally recite mantra twice for the first two repetitions, three times for the second two repetitions, and four times for the last two repetitions. End in forward bend position.

6.

POSTURE: Bhujangāsana.

EMPHASIS: To engage big muscles of back, stimulating movement of energy in body.

TECHNIQUE:

A: Lie on belly, head turned to right, with hands crossed over sacrum and palms up.

On inhale: Lift chest and right arm, turning head to center.

On exhale: Lower chest, sweeping arm behind back and turning head to left.

Repeat on other side.

B: From starting position:

On inhale: Raise both arms up.

On exhale: Bend elbows back towards ribs, and lift chest higher.

On inhale: Straighten arms again.

On exhale: return to starting position.

NUMBER: A four times each side, alternately. B four times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Keep knees and feet on floor. B: On exhale, Keep palms and elbows level at shoulder height.

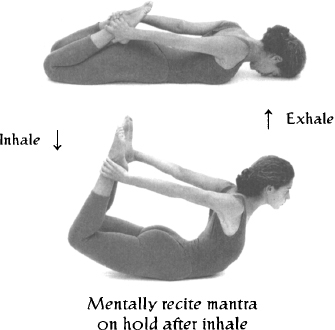

POSTURE: Dhanurāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch and expand chest, deepen inhale, and strengthen back and legs.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on stomach, resting on forehead, with knees bent and hands grasping ankles.

On inhale: Simultaneously, press feet behind you, pull shoulders back, lift chest, and lift knees off ground.

On hold after inhale: Mentally recite thou art with me.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift head forward, but do not collapse it backward. Keep knees not too wide. On hold after inhale: Recite mantra twice for the first two repetitions, three times for the second two repetitions, and four times for the last two repetitions.

8.

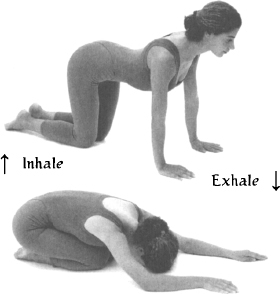

POSTURE: Cakravākāsana.

EMPHASIS: To stretch low back. To make transition from prone to sitting position.

TECHNIQUE: Get down on hands and knees, with shoulders vertically above wrists and with hips above knees.

On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly.

On exhale: Move hips back and down towards heels, lowering chest towards thighs.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lead with chest, keeping chin slightly down. Avoid compressing low back; rather, feel chest expanding. On exhale: Let chest lower toward thighs sooner than hips toward heels.

9.

POSTURE: Nāvāsana/Paścimatānāsana combination.

EMPHASIS: To stimulate and strengthen abdomen and low back. To stretch low back and legs.

TECHNIQUE: Sit with legs forward, back straight, and arms raised over head.

On exhale: Lean backward, lifting legs off floor and lowering arms, palms together, until parallel to floor.

On hold after exhale: Mentally recite thou art with me.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

On exhale: Bend forward, bending knees slightly, bringing chest to thighs, and palms to balls of feet.

Stay 2 breaths.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 3 times.

DETAILS: Nāvāsana: Keep low back rounded, eyes and toes at same level, and torso to legs at an angle greater than ninety degrees. On hold after exhale: Recite mantra twice for the first two repetitions, three times for the second two repetitions, and four times for the last two repetitions. Paścimatānāsana: Relax low back and belly.

10.

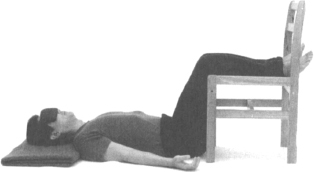

POSTURE: Śavāsana with support.

EMPHASIS: To rest.

TECHNIQUE: Lie flat on back, with arms at sides, palms up, and legs resting comfortably on a chair. Cover eyes. Relax body fully, keeping mind relaxed and alert to sensations in body.

DURATION: Minimum 3 to 5 minutes.

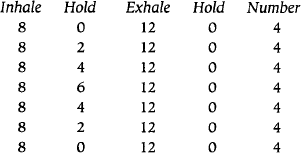

EMPHASIS: To progressively lengthen and then shorten hold after inhale.

11.

POSTURE: Prānāyāma, Antah Kumbhaka.

EMPHASIS: To progressively lengthen and then shorten hold after exhale.

To use thou art with me on hold after inhale.

TECHNIQUE:

A: Establish deep and equal inhale and exhale, with no breath retention.

B: Initiate and extend length of retention after inhale by mentally reciting two more mantras every two breaths, increasing from two repetitions to six progressively.

C: Reverse the process from six repetitions back to two.

D: Repeat A.

DETAILS:

The tamo guna can be characterized as a force of stability. When it predominates, however, a great inertia sets in. When this happens, situations that are difficult or unpleasant lead to feelings of helplessness, depression, and, in extreme cases, to drug addiction or even death. The tamasic quality of mind can be described as a state of dullness. Because in this condition there is no movement and no motivation to do anything, what is required is a shift of focus and an awakening of interest that can activate our energy.

Depression can be considered an example of a tamasic emotion. There are many different degrees and kinds of depression, ranging from a lack of direction and purpose in life; to grief due to loss; to chronic sadness, low self-esteem, or helplessness; to an acute clinical depression that can even lead to suicide. The following attitudes and emotions can be included under the general heading of depression: complacency, dejection, despair, disappointment, emptiness, gloom, grief, hopelessness, loneliness, melancholy, sadness, sorrow, self-pity, and shame. Depression differs from anger and anxiety in a fundamental way: while in both anger and anxiety, the body is flooded with the chemicals characteristic of the fight-or-flight response, in depression there is a low level of certain neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine and serotonin. Genetic research indicates that certain types of depression are inherited; but, whatever the cause, there is mounting evidence that depression significantly inhibits recovery from illness, disease, and surgical procedures. Depression and the other emotions mentioned above are characterized by a loss of energy, appetite, interest, and enthusiasm and are marked by a slowing down of the body’s metabolic rate.

A certain amount of depression is a normal reaction to the inevitable losses we suffer in life. However, abnormal or clinical depression is actually a serious illness and often leads to suicide. Thus, when recurring suicidal thoughts are present, it is best to seek professional psychiatric help.

One way to work with depression is to use a brahmana/langhana strategy. First, brahmana postures are used to increase physical activity and energy in the body and to raise the spirit; then langhana prānāyāma is used to reduce mental activity, especially the flow of negative thoughts, and to soothe the mind. This is particularly useful when the depression is accompanied by anxiety. Another appropriate method is that of pratipaksa—a method for assuming another point of view, which corresponds to cognitive reframing and is suggested by Patañjali. For example, a normally self-critical person would begin to recognize and focus on his/her positive qualities.

Other suggestions include getting involved in charitable work, helping others who are less fortunate; playing with or teaching young children, who are generally light and happy; and, if there is faith, getting more involved in prayer and/or a spiritual community. In addition, as with anger and anxiety, the support, caring, and touch of loved ones is an invaluable remedy to any condition in which the tamo guna is predominant. Finally, we also recommend that people suffering from depression avoid alcohol and refined sugar, spend time in nature, and, if their environments have a shortage of sunlight, use full-spectrum lights.

As with anxiety, conditions of depression are as variable as the people who suffer from them, and, as we have seen, a Yoga therapy practice is ideally adapted to the uniqueness of each individual. The sequence that follows offers an example of working with conditions of chronic depression and, though not prescriptive, is indicative of an approach to these conditions.

S.H. was a forty-five-year-old married woman. She had occasionally attended seminars I taught in Los Angeles. After about five years of seeing me once or twice a year in workshops, she told me that she had decided to come to Hawaii to work with me privately.

I had noticed, over the years, that her body was flexible. She was able to do many postures without much difficulty. I remembered, however, that she was not strong and that her breath was shallow. S.H. complained that she lacked stamina and fatigued easily. She also told me that she often had difficulty sleeping and in concentrating.

As we began to work together, she told me that she had not been able to overcome a deep sense of hopelessness that had been plaguing her for many years. She also told me that she did not have much energy or motivation and had reached a point where she was basically doing nothing.

In the beginning, S.H. told me that she had a good relationship with her husband, who was quite successful in his career, and that they were free of financial worries. They had no children.

As we worked together a little longer however, S.H. told me that her husband was very taken by his work and that they hadn’t spent “quality time” together for many years. She told me that they hadn’t gone out just to have fun or taken a vacation together in a long time. She said that though he was a good provider, she felt emotionally abandoned.

S.H. told me she had few friends. She said that she had stopped seeing them because she felt guilty about her depressed state.

S.H. told me that she had no enthusiasm for cooking and that she and her husband had gotten into the habit of eating out. They both drank wine, and she expressed to me that perhaps she “drank a bit too much.” She said she didn’t eat breakfast and usually stayed in bed late into the morning. She said she didn’t eat much during the day, except a couple of candy bars!

In my conversations with S.H., I learned that when she was a child, she had spent a lot of time in nature as a Girl Scout. She told me that she remembered that as a happy time. Coming to Hawaii had reminded her of those times, and she realized how much she missed being out in nature and in the company of good friends.

The strategy I developed for S.H. while she was is Hawaii included improved diet, increased physical activity, reconnecting to nature, and developing a personal practice.

We agreed that, at least for the month she was in Hawaii, she would get up early each morning, take a walk on the beach as the sun was coming up, and then do her practice before eating a healthy breakfast. I asked her to focus on the sunrise as she walked, and to keep that in her mind as she did her personal practice. I asked her to feel during her practice as if the sun was rising in her heart and a new day was dawning in her life. I also asked her to spend some time outside in the night looking at the stars before she went to bed and to visualize a happier future.

In addition, I asked her, at least while she was in Hawaii, to give up candy bars and wine. I encouraged her to contact the Sierra Club and go with the groups to hikes in the mountains. One day she came to see me full of excitement. She told me that some people she had met on a hike had invited her to go on a whale watching excursion. She told me that when a whale swam very near the boat she was on, she felt her heart open like she hadn’t felt in years. The word she used was “exhilarating.” She said that in that moment, she felt a happiness that she hadn’t felt in a long time.

We developed the following practice during that month we worked together. My intention was to strengthen her body, deepen her breathing, improve her concentration, increase her energy, help her sleep, and stimulate her interest in life. The use of simple to progressively more complicated series (vinyāsas) of linked movements were designed to increase her energy. The prānāyāma practice was designed to deepen her breath. And the meditation on the sunrise was designed to stimulate her interest in life.

I saw S.H. again the next time I went to Los Angeles, and she came to Hawaii with her husband the following year. She told me that the quality of her life had improved greatly since her last trip to Hawaii. She laughed and told me that she wasn’t sure if it was the Yoga practice or the whale! She told me she was spending more time with her husband and was sleeping better. She also told me that she had been inspired by the flowers in Hawaii, and had started getting up early in the morning to go downtown to the flower markets to buy flowers for her new hobby, making flower arrangements. She told me that she has been making gifts of the arrangements to her friends, who love them. Then she thanked me for the “sunrise in the heart” meditation, which, she assured me, she uses every morning.

1.

POSTURE: Apānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To gently compress belly while stretching low back. To warm up body with gentle movements.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with both knees bent toward chest and feet off floor. Place each hand on its respective knee.

On exhale: Pull thighs gently but progressively toward chest.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 12 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Pull gently with arms, keeping shoulders relaxed and on floor. Press low back down into floor and drop chin slightly toward throat.

2.

POSTURE: Dvipāda Pitham.

EMPHASIS: To further warm up body by engaging thighs and buttocks.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, knees bent, and feet on floor, slightly apart and comfortably close to buttocks.

On inhale: Pressing down on feet and keeping chin down, raise pelvis until neck is gently flattened on floor, while raising arms overhead to floor behind.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift spine, vertebra by vertebra, from bottom up. On exhale: Unwind spine, coming down vertebra by vertebra.

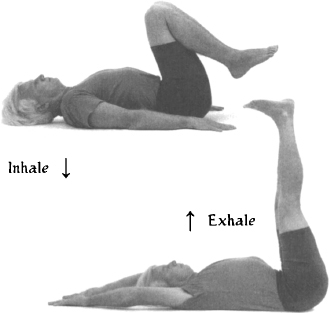

POSTURE: Ūrdhva Prasārita Pādāsana.

EMPHASIS: To extend spine and flatten it onto floor. To stretch legs. To progressively engage the larger muscles.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, legs bent, and knees in toward chest.

On inhale: Raise arms upward all the way to floor behind head and legs upward toward ceiling.

Stay in stretch 2 full breaths.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 4 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Flex feet as legs are raised up ward. Slightly bend knees, keeping angle between legs and torso less than ninety degrees. Push low back and sacrum downward. Bring chin down. While staying in position, on exhale, flex knees and elbows slightly; on inhale, extend arms and legs straighter.

4.

POSTURE: Vajrāsana/Cakravākāsana Vinyāsa.

EMPHASIS: To increase activity in body by combining two postures. To introduce lengthening of inhale.

TECHNIQUE: Stand on knees with arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, bringing arms to floor in front of you.

On inhale: Lift chest up and away from belly, coming forward onto hands.

On exhale: Tighten belly, round low back, and bring chest toward thighs.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Make inhalation progressively longer with each repetition. Bring chest to thighs before hips to heels. Avoid pulling spine with head, overarching neck. Lead with chest, keeping chin slightly down. Avoid overarching low back; rather, feel stretching in belly. On exhale: Round low back without collapsing chest over belly. Avoid increasing curvature of upper back. Let chest lower toward thighs sooner than hips toward heels.

POSTURE: Uttānāsana/Ardha Utkatāsana combination.

EMPHASIS: To activate big muscles of body, to stimulate cardiovascular and respiratory function.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with feet slightly apart, arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, bending knees slightly, bringing chest to thighs, and palms to sides of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

On exhale: Bend forward, bending knees until thighs are parallel to ground, hips are at knee level, chest to thighs, and palms to sides of feet.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Make exhalation progressively longer with each repetition. Bend knees to facilitate stretching in low back. Push heels firmly, and reach arms forward. On inhale: Lift chest up and away from thighs, flattening upper back without exaggerating lumbar curve. Keep knees bent until last part of movement.

POSTURE: Pārśvottanāsana/Vīrabhadrāsana combination.

EMPHASIS: To stretch and strengthen muscles of back and legs.

To expand chest and flatten upper back. To increase hold after inhalation.

To continue to stimulate cardiovascular and respiratory function.

TECHNIQUE: Stand with left foot forward, right foot turned slightly outward, feet as wide as hips, and arms over head.

On exhale: Bend forward, flexing left knee, bringing chest toward left thigh and bringing hands to either side of left foot.

On inhale: Lift torso two-thirds of the way up while bending left knee, arching back, and bringing arms out to sides and shoulders back.

After inhale: Hold breath 4 seconds.

On exhale: Remain in position.

On inhale: Raise arms straight up over head.

On exhale: Return to forward bend position.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 4 times each side.

DETAILS: Stay stable on back heel and keep shoulders level throughout movement. Vīrabhadrāsana: On inhale, keep hands and elbows in line with shoulders. Feel opening of chest and flattening of upper back, not compression in low back. Keep head forward.

POSTURE: Vajrāsana/Ūrdhva Mukha Śvānāsana combination.

EMPHASIS: To further energize system by engaging musculature of upper body, expanding chest, and stretching belly.

TECHNIQUE: From a kneeling forward bend position, with hands on ground in front of body.

On inhale: Stretch body forward and arch back, keeping only hands and from knees to feet on floor.

Stay 1 breath.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Expand chest, stretch belly, and avoid compressing low back. On exhale: In arched position, push mid-thoracic forward. End in forward bend position.

8.

POSTURE: Dvipāda Pitham.

EMPHASIS: To relax upper back, shoulders, and neck.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with arms down at sides, knees bent, and feet on floor, slightly apart and comfortably close to buttocks.

On inhale: Pressing down on feet and keeping chin down, raise pelvis until neck is gently flattened on floor, while raising arms overhead to floor behind.

On exhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 6 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Lift spine, vertebra by vertebra, from bottom up. On exhale: Unwind spine, coming down vertebra by vertebra.

POSTURE: Apānāsana.

EMPHASIS: To relax lower back.

TECHNIQUE: Lie on back with both knees bent toward chest and feet off floor. Place each hand on its respective knee.

On exhale: Pull thighs gently but progressively toward chest.

On inhale: Return to starting position.

NUMBER: 12 times.

DETAILS: On exhale: Pull gently with arms, keeping shoulders relaxed and on floor. Press low back down into floor and drop chin slightly toward throat.

10.

POSTURE: Prānāyāma/Anuloma Krama, 2 stages.

EMPHASIS: To expand chest and deepen inhalation capacity. To increase energy and confidence.

TECHNIQUE:

Exhale deeply and fully.

Inhale 1/2 of breath in 4 to 5 seconds.

Pause 4 to 5 seconds.

Inhale remainder of breath in 4 to 5 seconds.

Pause 4 to 5 seconds.

Exhale slowly and fully.

Repeat.

NUMBER: 8 times.

DETAILS: On inhale: Expand chest from pit of throat to sternum. Then expand abdomen from solar plexus to pubic bone.

11.

POSTURE: Seated Rest.

EMPHASIS: To rest without lying down.

TECHNIQUE: Sit comfortably with eyes closed. With a relaxed mind, notice the sense of well-being stimulated by the practice.

DURATION: Approximately 5 minutes.

In summary, the therapeutic methods of the Yoga tradition are based on the ideas of viyoga (removing something undesirable) and samyoga (linking to something desirable). From the point of view of emotions, viyoga refers to the reduction of rajasic states of agitation (e.g., emotional states categorized under the general headings of anger and anxiety) and tamasic states of dullness (e.g., emotional states categorized under the general heading of depression); and sa yoga refers to the sustained effort to develop in ourselves the sattvic state of clarity and contentment. Yoga therapy is used to help people stabilize their emotional lives so they can begin to use Yoga as a process of spiritual transformation; and, for those with rather serious problems, it can function as a “life raft” in the process of getting out of troubled waters. But Yoga therapy is only a preparation for the true intention of Yoga, which is to function as a “launch pad” to new possibilities of personal evolution. While this book has focused on the developmental and therapeutic aspects of Yoga, our next book will focus on Yoga as a spiritual practice.

yoga refers to the sustained effort to develop in ourselves the sattvic state of clarity and contentment. Yoga therapy is used to help people stabilize their emotional lives so they can begin to use Yoga as a process of spiritual transformation; and, for those with rather serious problems, it can function as a “life raft” in the process of getting out of troubled waters. But Yoga therapy is only a preparation for the true intention of Yoga, which is to function as a “launch pad” to new possibilities of personal evolution. While this book has focused on the developmental and therapeutic aspects of Yoga, our next book will focus on Yoga as a spiritual practice.