“I have no idea what’s going to be on the exam.”

“I just don’t test well.”

“Those questions really caught me by surprise.”

“I can’t seem to think fast enough on exams.”

“I don’t know how to prepare for this test.”

“I can’t control how I do on tests—sometimes I get lucky, sometimes I don’t.”

“I crammed so hard for this exam, but then I blanked out.”

“That test was really long—I just made up answers for the last section.”

“I thought I got it right, but when I asked Tom, he got something totally different, so now I don’t know.”

“I read all the assigned material—I don’t know why I didn’t do better.”

“I could’ve done better if I had more time to study.”

Do any of these sound familiar to you? They’re common sentiments among students, but they’re not things that you should be saying. Believing that you’re not a good test-taker, that you can’t predict what’s going to be on the exam, or that you have no control over the situation are self-fulfilling prophecies. Because guess what: you can become a better test-taker, and you are in control over your test destiny.

Am I saying that exams are never unfair or that there are some things you just can’t prepare for? No, of course not. But taking a test is like any other skill: it requires preparation, strategy, determination, and lots and lots of practice. Luckily for you, your teachers have taken care of the practice part.

Getting As is about more than understanding the material—you’ve got to know your test, too. As soon as your teacher announces the exam, make sure you can answer the following questions:

1. What material will it be on?

2. Is it cumulative, or is it only on what’s been covered since the last test?

3. How much of your grade is it worth?

4. What kind of questions will it have—multiple-choice, true/ false, short answer, essays, or something else?

Most teachers waste no time providing this information, but if they’re keeping mum, don’t be afraid to raise your hand or go up to them after class. Just stay away from the all-encompassing question, “What’s going to be on the test?” because this sounds like you’re looking for the answer key. Questions such as “Will the test be cumulative?” and “What will the format be?” are a bit more polite. Don’t panic if your teacher purposefully withholds information. Look at tests from earlier in the semester for clues about format and question types. If it’s the first test of the term, be prepared for all contingencies, and remember that your classmates are in the same suspense-filled boat.

When preparing for your test, don’t forget about the syllabus! Although your teacher gave it to you a long time ago, it may still have information about what’s fair game on exams. You should also reread your notes from the first day of class, as that’s when teachers discuss their vision for the rest of the semester.

If you’re lucky, your teacher will give you an exam from a previous year. Work out all the problems by yourself under timed conditions, whether or not you already have the answers; and if anything’s unclear, ask your teacher, TA, or study group for help. Review these exams at least two or three times, as your test is bound to bear a striking resemblance.

Looking over tests you took earlier in the semester is one of the best ways to improve your performance on future exams. Read through the comments and examine the questions for patterns and preferences. For example:

• What did your teacher like or dislike about your essays? Should you have included more examples? Did you write too much or not enough? Did you answer the question?

• Are the questions more concerned with the “big picture” than with nuances and details, or vice versa?

• Do you have a tendency to over-analyze questions? Do you look for tricks in the simplest of statements? Most test questions are pretty straightforward, and you may be hurting your grade by reading too much into them.

• Did the true/false questions almost always turn out to be true?

• Were most of the questions based on problems you did in class or for homework?

• Do the exams tend to be on the long or short side? Can you answer the questions at a leisurely pace, or do you have to rush through them with superhuman speed?

• Was everything on the exam covered in class? As discussed earlier, many teachers will test you on something only if it was included in their lecture. This often means you can study exclusively from your notes—if they’re detailed enough.

The answer is: before the exam is even announced. How is this possible, you ask? Easy—if you’ve been keeping up with the homework and readings and reviewing your notes, you’ve been preparing for this test all along! When you know you have an exam coming up, however, it’s time to engage in more directed study. Based on what you know about the class and the test itself, do you have to focus on your notes or your books? Is it a test where you have to know facts as well as concepts? Are all topics equally important, or will some be emphasized more than others? Once you know what you have to study, it’s time to…

Is your idea of studying rereading your notes and books as many times as humanly possible? When you read, do you stick your head in a book and never come out? If so, you’re engaging in something called passive studying, which is a very passé thing to do. Make your study time more productive by actively reviewing the material. Active studying means you do stuff to make the information stick, such as asking questions—lots of them—as you review. Questions like:

• What “big idea” does this represent or is this an example of?

• When would I apply this formula?

• What were the causes of this event?

• How does this author compare to others we’ve read?

• Why is this important?

• What are some examples of this theme?

Some other active learning techniques are putting key concepts in your own words and saying them out loud for extra reinforcement, making diagrams for complicated processes or visualizing them in your head, and explaining a concept to somebody else. For STEM classes, redo exercises from class and homework and do additional problems from the book.

One of the best active studying techniques is to create review sheets, which are essentially summaries of your notes and readings. Not only are these great to study from in the days leading up to the exam, but the act of preparing them helps you break down the material, group things together, ingrain them in your memory, and fill gaps in your knowledge. Your study sheet can be one or several pages, but it should be short enough to read in a single sitting.

The type of review sheet you create depends on the class and the type of exam, but here are some general guidelines. For STEM classes, it should contain formulas, key terms, and examples of the major types of problems you’ve seen in class and homework. For humanities classes, it should include major themes as well as key dates, names, and terms. If the test will include questions about different readings, it should list the texts, the authors, and the main points of each.

Here’s an excerpt from a review sheet I created for a college class called Literature Humanities. Since the test was going to consist of a couple of essay questions about the books we had read, I wanted to be really clear on the Big Ideas—so I went through my class notes and identified the major themes of each text.

• Life as a spectacle, a play, art; making art out of life.

• Reading as a seduction.

• The primacy of individual interests.

• Turning love or passion into art; the rationalization of the irrational.

• Compassion, pity are infectious.

• Human truth vs. absolute truth.

• Culture facilitates sexuality.

• The instability of language.

• Words create their own reality; equating the figurative with the literal.

• Faith and reason are not compatible.

• Disjunction between body and mind.

• We can know ourselves only through artifice or culture.

• Change is the only constant.

The review sheet made it much easier to compare and contrast the texts and predict potential essay questions. For example, I noticed that the nature of language and the struggle between nature and culture kept showing up again and again—so I made sure I had some good examples of these themes ready to go for the exam.

Review sheets are especially handy when it comes to foreign languages. All those conjugations and grammar rules can really add up, and having them in one place helps you notice subtle but important details. You should also include plenty of examples so you’ll remember how to use these rules months or even years from now. Here’s an excerpt of a review sheet I created for German—or, as Mark Twain called it, “The Awful German Language.”

Definite Articles (the) |

||||

|

Masc. |

Fem. |

Neuter |

Plural |

Nominative |

der |

die |

das |

die |

Genitive |

des |

der |

des |

der |

Dative |

dem |

der |

dem |

den |

Accusative |

den |

die |

das |

die |

(These are all different ways of saying “the” in German. The cases—nominative, genitive, etc.—indicate the word’s grammatical function in the sentence.)

Possessive Adjectives:

mein (my), dein (your), sein (his, its), ihr/Ihr (her, their/your), unser (our), euer (your)

Comparative: ends in – er(–).

Superlative: ends in – st(–).

Or use “am […] –sten” (example: am kleinsten = the smallest)

(Here I give some examples of verb tenses and conjugations.)

Present Tense Example:

machen (to do):

ich mache (I do)

du machst (you do)

Sie machen (you do)

er macht (he does)

sie macht (she does)

es macht (it does)

man macht (people do)

wir machen (we do)

ihr macht (you do)

Sie machen (you do)

sie machen (they do)

Preterite Example: take stem, add –te

machen:

ich machte (I did)

du machtest (you did)

man machte (people did)

wir machten (we did)

ihr machtet (you did)

sie machten (they did)

Future Tense: werden + infinitive (or present tense with future implied).

Example: ich werde…machen (I will do)

Passive Voice: werden + past participle.

Example: ich werde…gesehen (I am seen)

People who study learning for a living have long known about these grade-boosting methods, but many students still haven’t heard about them. Here’s how you can incorporate these scientifically proven strategies into your studying.

I know what you’re thinking—“I get enough tests in class. Now I’ve got to do them at home, too?” But quizzing yourself is easier than you may think, and research shows it’s one of the best ways to learn. In a 2006 study by Washington University in St. Louis, students who were tested repeatedly on a reading passage remembered more than 60 percent of it one week later, compared with 40 percent remembered by a group that had only read it a couple of times. This was despite the fact that the latter felt more confident about their retention of the material.74

A Kent State study has shown that students retain foreign vocabulary better when they’re asked to recall the meaning of words rather than study them side by side.75 And in a recent survey of 324 under-grads, researchers confirmed that self-testing is significantly associated with higher GPA.76 Quizzing yourself is a more powerful and efficient method than reading the material over and over and over again—so although it takes a little planning and initiative, you’ll actually save time and retain more in the end.

So how can you make self-testing part of your everyday study routine? For starters, if you’re given a practice test with solutions, do the questions by yourself before looking at the answers. Similarly, when studying flash cards and lists, don’t look at the answers until you’ve tried coming up with them on your own.

You should also quiz yourself on the readings. You can often find ready-to-use questions at the end of textbook chapters. If these aren’t available, try making questions out of the headings of each section. However, don’t just glance at the questions and say, “Yeah, I could answer that.” For best results, write down your answers on a piece of paper or say them out loud.

Switching between distinct but related tasks during a study session, instead of focusing on one thing the entire time, can do wonders for your comprehension. (Learning experts call this “interleaving.”) For example, if you’re studying a little español, don’t just memorize vocabulary words for hours on end—mix it up with reading a story in Spanish, listening to a language CD, and reviewing grammar.

Why does interleaving work? Because it forces your brain to make connections between things: you have to compare concepts, figure out when to apply one method and not another, and put what you learned into practice. Perhaps just as importantly, switching between topics makes studying less boring! It’s like when you go to the gym—would you rather spend the whole time doing stomach crunches, or taking turns between that and push-ups, jumping jacks, and running on the treadmill?

Simply put, spacing is the opposite of cramming, and it’s a powerful tool for getting better grades. According to learning experts, recall and comprehension improve when you spread out your studying rather than lump it all together.77 In other words, it’s better to study an hour tonight, an hour on the weekend, and an hour a week from now than to study something for three hours in a row. You’re not putting in more time or effort; you’re just getting more out of it.

Pretty cool, huh? No one’s quite sure why spacing works, but it could be because it forces you to recall what you’ve learned, compare it to what you’re learning now, and pinpoint and correct misunderstandings. If you study everything in one go (called “massing”), you don’t have that opportunity.

When you study, try making several passes over the material, leaving a few days between each pass. You’ll find that each time you’ll absorb a little more, make more connections, and see the big picture more clearly. For the first pass, skim the material to prep your brain for what’s coming. Next, read things slowly and carefully. At this stage you may feel like you’re not accomplishing much, but when you look at the text again, you may be surprised by how much clearer it’s become. Your passes through the material will get faster and more productive as time goes on.

Spacing and interleaving are even more effective when used together. This isn’t hard to do, since interleaving naturally spaces out your review of a topic. Let’s say you’re learning four new things—A, B, C, and D—which can be distinct but related topics in any area. So, by applying spacing and interleaving, your study sessions should look something like this:

ABCD CABD BADC CBDA

As you can see, your review of each topic is spaced out because you’re interleaving it with the other three. Note that it’s better to mix things up than to do them in the same order every time (ABCD ABCD ABCD ABCD), so you don’t get the right answer simply by predicting what’s next.

To make spacing and interleaving part of your everyday study habits, have a strategy for every test. Before you start preparing, think about how you can break up the material into distinct but related topics, and alternate between them as you study. For STEM classes, do practice problems out of order. Let’s say your math teacher tells you to do ten questions from Chapter 1 and another ten from Chapter 2 for homework. Instead of answering them sequentially, alternate between questions from the first and second chapters. This forces you to think about which rules and formulas you have to apply. Just make sure everything’s in order when you hand in the assignment!

One of the most important applications of these learning techniques is to start early and space it out. Study every subject a little at a time rather than condensing it into one massive review session. This is another way of saying, “Do not cram!” Cramming leads to very poor retention of material—what you study will be in your head one day, out the next.

Memorization has gotten a bad rap recently. Lots of students, and even some educators, say that being able to reason is more important than knowing facts; and besides, why bother committing things to memory when you’ve got Google? My response to this—after I’ve finished inwardly groaning—is that of course reasoning is important, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t know facts as well. It’s not like you have to choose between one or the other. Besides, facts give you a foundation on which to reason about things.

As for depending on Google, it’s hard to have an intelligent conversation if you have to look something up every ten seconds. And it’s never good to be reliant on external devices—what if you can’t access the Internet, or you lose your iPhone, or your battery dies? Whether you agree with this or not, most teachers still require you to know things by heart. The following are some active learning techniques that’ll make you a master memorizer.

Flash cards are a cheap and easy way of learning material. You can take them wherever you go and study as much or as little as you want; you can shuffle them up and group them into stacks; you can test yourself or have a friend quiz you. But believe it or not, there’s been a lot of research on this seemingly simple method of studying.

One of the findings from this research is that it’s better to use one large stack than several smaller ones. This goes back to the theory of spacing: the bigger your stack, the greater the space between items. Take, for example, a 2009 study in which students who reviewed vocab from a stack of twenty flash cards had much better recall than those who studied the same words in four stacks of five cards each.78

You should also think twice before dropping a card from your stack, even if you feel like you know it. In a 2008 experiment by Nate Kornell and Robert Bjork, one group of students was allowed to set aside flash cards they thought they knew, while the others had to leave the deck intact. When they were tested on the material—a list of Swahili words—immediately afterward and a week later, the no-drop group scored significantly better.79

This might seem to go against common sense. After all, the more easy items you remove, the more you’ll get to review the ones giving you trouble, right? But as with many things, it’s not that simple. You may know that wingu means “cloud” in Swahili, but leaving it in your deck will help you retain that knowledge. Plus, as we saw above, it’s better to study from a large stack than a small one—and the more cards you take away, the punier your stack becomes.

If you want to get fancy with your flash cards, use something called the Leitner system. In this method, which is based on the theory of spaced repetition, you have several stacks or boxes of flash cards. Let’s keep it simple and say you have three boxes. The first box, which you review the most often (say once a day), contains items you got wrong or haven’t seen before. When you get one of these cards right, you put it in the second box, which you review less often (every other day).

When you get a card from the second box right, you put it into the third box, which you review even less often (maybe every four days). Whenever you get something wrong from boxes 2 or 3, you put it back in the first box. That way, you review the ones you have trouble with more often, and you never stop reviewing any of the cards.

Don’t want to worry about when to study what, or where to store all those boxes? No problem! Download a free electronic flash-card program such as Anki (http://ankisrs.net/) or the Mnemosyne Project (http://www.mnemosyne-proj.org/). Just type in what you want to memorize and let the software do the rest.

Beware of spending so long making flash cards that you don’t have enough time to review them! When days are short and your list is long, don’t bother rewriting every item on a 3×5-inch piece of paper. If the material’s already in one convenient place—for example, at the end of a chapter, in the back of the book, on the Internet, or in a handout your teacher gave you—just study directly from the source. To test yourself, simply cover up the answer column with your hand. If you get something wrong, make a mark next to it in pencil so you can come back to it later. And don’t forget to test yourself in both directions. If you’re studying Spanish vocab, make sure you can go from English to Spanish as well as Spanish to English.

One problem with studying from lists, however, is that people tend to remember the beginning and the end better than the middle. (This is known as the serial position effect.) A simple way to prevent this is to start reviewing from a different place each time. Studying from a list can also make it difficult to identify terms out of order, so it’s a good idea to pick items from the list at random when you’re testing yourself.

You know how in the opening credits of The Simpsons, Bart is always writing something twenty times on the blackboard? Things like, “The capital of Montana is not ‘Hannah’” and “I will not eat things for money”? Well, this may be Bart’s everlasting punishment, but it’s also an excellent way to burn things into your brain.

Grab a pad of paper and write out things like Spanish verb tenses, physics formulas, and the dates of Revolutionary War battles. Write each item ten to twenty times per sitting, until you feel like you could conjugate the first-person preterite of hablar in your sleep.

Note: Do not just copy things from a book as you write; you should be actively recalling them from memory to get the best results.

In a 2010 study, people who read half a list of words silently and spoke the other half recalled the spoken words much better than the silent ones. In other words, saying things out loud seemed to help them remember it.80 So does this mean you should stand up in the middle of the library and give an impromptu reading of The Fundamentals of Calculus? Fortunately for your fellow students, the answer is no. It turns out that this memory boost occurs only when you read things out loud once in a while, not when you do it all the time.

Test subjects who verbalized the whole list of words remembered them no better than a group who read the entire list silently. If you start saying everything out loud, it’s no longer a distinctive, memorable event. So save your breath for the really important stuff that’s more likely to show up on tests—key terms, formulas, big ideas, and so on. By the way, if you’re in public and don’t want people to think you’re crazy, you can get the same benefit from silently mouthing the words.

Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally, My Very Energetic Mother Just Served Us Nine Pizzas (although the Pizzas have since disappeared!), Roy G. Biv—do these sound familiar to you? You probably learned lots of mnemonic devices as a kid, and what’s more, you probably still remember them.

Rhymes, acronyms, mental images, silly phrases, and memorable word groupings are great ways to learn material at any age, and you don’t have to wait for somebody to make them up for you. If you’re drawing a blank, grab a dictionary and pick a word based on the first letter of each term you’re trying to remember, or plug them into one of these handy mnemonic generators:

• http://spacefem.com/mnemonics/

• http://human-factors.arc.nasa.gov/cognition/tutorials/mnemonics/index.html (The Mnemonicizer, from the people who brought you the Space Shuttle!)

If you take public transportation, this is an excellent time to stretch out those synapses. There’s something about the way the wheels on the bus go round and round, or the steady hum of the engine, that primes the brain for memorization. While it may not be the best time to study, say, multivariate calculus, commuting is great for relatively straightforward tasks like reviewing outlines, lists, flash cards, or the glossaries at the back of your books. If you get jostled around a lot, use spiral-bound index cards instead of the loose ones so your stuff doesn’t go flying.

Not really. While a lot of students won’t look at a topic once they feel like they know it, a really good student will keep going until he or she has got it practically by heart. (Cognitive psychologists call this over-learning.) In the heat of an exam, it’s not just about whether you know something, it’s also about how fast you can recall it. If you have to keep dredging things out of your memory like a stick out of mud, you may not have time to finish the test or check your answers. Plus, it’s much easier to blank out on things you only know superficially. Overlearning makes coming up with the right answer practically effortless.

While there’s no such thing as over-studying, there is such a thing as spending too much time on one thing and not enough time on something else. If you have a lot of topics to cover, make sure you devote enough time to each. Interleaving will help you avoid this problem.

It happens to all of us sooner or later—we find ourselves in a class so painful that it makes a root canal look like a walk in the park. You have no interest in it. It’s hard, it’s boring, and the mere sight of a book on the subject makes you want to run the other way. So how do you make it through this term of torture?

Try bargaining with yourself. If you can’t bear the thought of reading a chapter in depth, say that you’ll skim it for now. When you go back to it later, it’ll be easier to digest. Can’t imagine devoting a whole hour to this detestable subject? Commit to ten or twenty minutes—a little is better than nothing at all. And when you get to the end of that time, you might find yourself saying, “Hey, this isn’t as bad as I thought. Maybe I could go for a few more minutes.”

You should also make yourself extra comfortable when it’s time to study your least-favorite subject. Go to your best study spot, put on some relaxing music, maybe take a shower before you crack open the book. Try to study when you’re most relaxed. You should be awake enough to concentrate, but not so awake that you’re too restless to read something incredibly dry and boring. I find the best times for this are shortly after waking up and a little before I go to bed.

And don’t forget to reward yourself. You know the deal—eat some chocolate, check Facebook, go for a walk, watch TV, chat with a friend. Give yourself something to look forward to after struggling through an assignment.

When studying a subject you hate, make sure you know what the purpose is. It might not always be obvious, but it is there. If you’re a high school student with dreams of becoming an English major, you may wonder why you have to suffer through pre-calculus. Keep reminding yourself that it’s bringing you one step closer to your goal of getting into college. Universities want to see advanced coursework in a variety of subjects, not just the one you plan to specialize in. Besides, lots of people change their plans. What if you decide to get a BA in English and do pre-med? You’ll be glad you stuck it out with pre-calc.

You may think that studying’s all in the mind, but it’s got a physical side as well. The right environment can do wonders for your concentration. You should be comfortable when you study, because you’re going to be doing a lot of it! If you’re constantly thinking about the lighting or the temperature or your aching back, you might not give your work the attention it deserves. Here’s how to make studying a more pleasant experience.

Everyone knows you should study in a quiet, well-lit place with few distractions. But where should this place be? At home, in the library, in the student lounge?

Research shows that you may be better off alternating where you study. In a 1978 experiment by Robert Bjork and others, college students were given a list of forty words to memorize. One group reviewed the list in two different rooms, while the others spent all their time in a single location. When they were tested on the vocab, the nomads recalled an average of 24.4 words, compared to 15.9 by the stationary group.81

Being in different environments seems to enrich the information that’s being stored in your brain, making it stay there longer. So consider staking out a number of learning zones—the rooms in your house, the library, a quiet café, a student lounge, a park—and switching locations every few hours or going to a different place each day. Remember that all of your study spots should be relatively quiet and distraction-free. If you have after-school access to the room where the test’s being given, you may be in luck. Researchers have found that students perform even better when they take exams in the same environment as where they studied.82

The fact of the matter is, when you’re a busy high school or college student, you’ve got to study whenever you can. However, research shows that some times are better for learning than others. Studying in the afternoon or evening seems to have the best effect on long-term memory, even for those who say they’re morning people.83

Researchers have also found that learning something shortly before bedtime will help you retain it. In a 2012 University of Notre Dame study, for example, test subjects recalled a list of word pairs better when they went to sleep soon after studying than when they learned it early in the day.84 So try memorizing things like facts, dates, and formulas before calling it a night. This has the added benefit of making it a cinch to fall asleep!

Make sure your study space is on the cool side and has good ventilation. In 2004 and 2005, researchers found that students performed better on exercises when the temperature was lowered from 77 degrees to 68 degrees, and when the air supply rate was increased. Although the number of errors they made didn’t change significantly, they did get the exercises done faster.85

Did you know that going green is good for the environment and your grades? It’s true—you can increase your productivity simply by adding plants to your work space. In a 2010 study, test subjects performed several demanding cognitive tasks in an office setting with four indoor plants, while another group did the same tasks in a room minus the greenery. The result: the plant people’s performance improved after completing the first task, but the other group’s did not.86

No one’s quite sure why plants have this effect on people. It could be because of the oxygen they produce, or maybe the presence of nature helps people relax and focus, or perhaps it’s a combination of the two. Whatever the case, get yourself down to the plant store and pick up a few hardy specimens.

If you’re in a classroom where there isn’t any greenery, try to sit by the window—just having a view of the great outdoors can improve performance. And if you live in a house with a backyard, or if your campus is a landscaped wonderland of green meadows and rolling hills, this is the perfect opportunity to study outside. Natural light, fresh air, and plants are all excellent study aids.

Think of your brain as a muscle. You wouldn’t go to the gym and work out for hours without taking a breather, would you? Well, you shouldn’t shut yourself up in a room and study that way, either. There’s no question that breaks help prevent burn out. In a 2011 study by psychologist Alejandro Lleras, for example, test subjects who worked nonstop on a computerized task for fifty minutes showed a decline in performance, while those who took two brief breaks were as attentive at the end of the task as they were in the beginning.87

Although you shouldn’t force yourself to stop working if you’re in the zone, doing something else when your mind starts to drift will help you get back on track. Breaks are also useful because you remember the first and last things you study better than the stuff in the middle. The more breaks you take, the more firsts and lasts you’ll have stored in your memory.

Can’t stop fidgeting when you study? Does the thought of sitting quietly in the library for hours make you go off the deep end? Well, take heart! There’s no law that says you have to sit still to learn. If you have access to a treadmill, grab a book and take a nice, long stroll as you read—or just walk around your room while you’re holding the book. (Make sure you get rid of all obstructions first.) Squeeze a stress ball or chew some gum to relieve tension while you’re stuck in the classroom.

Cats are usually more than happy to do this—in fact, you may have trouble keeping them off keyboards and books—and dogs will often serve as well. Few things are more relaxing than having a warm, furry creature next to you as you study.

In the early ’90s, Mozart CDs flew off the shelf as news came out that listening to this classical composer could raise your IQ. Unfortunately, later studies revealed that playing Eine kleine Nachtmusik would not turn you into a genius—but that doesn’t mean Mozart has no impact on your brain. The real effects of his music are much more subtle and complex.

Let’s take a look at a 1999 experiment by Kristin Nantais and E. Glenn Schellenberg in which test subjects performed spatial reasoning tasks after hearing a piece by Mozart, listening to a Stephen King story, or sitting in silence.88 The result: the people who preferred Mozart did better after listening to the music; the ones who preferred the story did better after hearing the King tale; and both groups outperformed the ones sitting in silence. (It’s worth noting, though, that the people who preferred Mozart did the best overall.)

What seems to be happening here is a psychological phenomenon known as arousal—and no, I’m not talking about anything dirty! In this case, arousal is a measure of mental stimulation. Too little arousal, and people are bored and unmotivated; too much, and they’re stressed out and anxious. Get it just right, and their performance skyrockets. When you like something—such as music or a story—your mood and concentration tend to improve, which in turn can raise your score on cognitive tests. So as it turns out, Mozart may give your brain a boost after all—but only if you like Mozart.

And lots of people do like Mozart, especially when they’re studying. It’s calming, it’s not too distracting, and it puts you in a studious frame of mind. Perhaps more importantly, you can use it to block out annoying background noise. I have a playlist of “study music” ready to go on my iPod, and it’s a lifesaver when I have to read in a public place. It also comes in handy when I’m by myself and things are a bit too quiet. I don’t only listen to Mozart, however; I also play Bach, Boccherini, Vivaldi, Schubert, and many others. My favorite pieces for studying are Mozart’s violin concertos, which I’ve listened to nearly every day since junior high school! Whether or not Mozart has improved my IQ, it does wonders for my concentration.

You don’t have to limit yourself to Mozart or classical, but there are some general rules to follow when choosing a study soundtrack. The music should fade into the background, not demand your attention. Make sure it’s instrumental only, as lyrics interfere with learning. You use the same part of your brain for studying as you do for listening to music with words. That means that Jay-Z, Lady Gaga, and Beyoncé are out.

Study music should have a steady rhythm and a relatively constant volume. And it should be upbeat rather than sad or angry, since songs that produce positive emotions are more likely to help you learn. In a 2001 experiment by William Thompson, E. Glenn Schellenberg, and Gabriela Husain, test subjects who listened to a lively Mozart sonata did better on a spatial reasoning task than those who heard a sad adagio by the composer Albinoni.89 If you don’t like classical, some other likely candidates are smooth jazz, electronic music, and movie soundtracks.

Lots of people, including some education experts, will tell you that study groups are the way to go. They can make studying more fun, help students stay motivated, and give them the opportunity to learn from one another. And this is all true—up to a point. While study groups can be good in certain situations (which we’ll discuss later), they have many hidden dangers—such as leading you to rely on others for explanation and motivation when these things should really come from inside yourself.

The social aspect can make it difficult to concentrate and think critically. Seeing somebody working on a different but related task can actually slow you down, according to a 2007 University of Calgary study by Tim Welsh.91Perhaps even more troubling, people in study groups may give you wrong information. Your classmates probably don’t know more and may even know less than you, so all too often it becomes a case of the blind leading the blind. You might be better off getting help from the real experts: your textbook, your TA (if you have one), and your teacher.

With that said, there are plenty of situations where it is smart to join the crowd. For example:

• You have a problem staying focused, and working with others helps keep you on track. Think of it as AA for procrastinators.

• You’re an aural learner—that is, you learn best by listening.

• You want to practice conversation for a language class.

• The other people in the group really know their stuff, and there’s a lot you can learn from them.

• You can’t go to a teacher or TA for help.

• You’ve finished studying all the required material and want to test your knowledge with others.

• You want to go over exercises for a class, and group discussion is allowed. (Make sure you know your teacher’s policy on this, because the last thing you want is to be accused of cheating.)

And if you do join a study group, make sure you follow these six simple rules:

1. Don’t let the group get too big. Things might get out of control with more than six or seven people.

2. Stay away from groups that use studying as an excuse to PARTAAAY!

3. Don’t hesitate to ask a question, give your opinion, or help someone who’s having trouble.

4. Choose someone to be “the leader” to keep the group on track, or take turns if no one wants this role for the entire semester.

5. Don’t split up homework assignments among members of the group. It’s much harder to learn the material if you don’t do all the questions—and besides, how do you know something’s done right if you don’t do it yourself?

6. Have a specific goal for each meeting. What are you trying to accomplish—is it working on homework problems, trying to understand a concept, or discussing a chapter in a book?

So far we’ve been discussing how to study, but now let’s turn our attention to the equally important but often overlooked question of how much to study. (In this context, studying refers to reading, doing homework, and any other preparation for a subject outside of class time; doing a math problem or reading an assigned text counts just as much as cramming for an exam the following day.) You may be wondering what a “normal” amount of study time is for American students. There’s no one answer, since it varies from school to school, region to region, grade to grade, and so on, but here’s some info to give you an idea.

High school:

• 63 percent of high school sophomores spend ten hours or less a week on homework.93

• Most high school students spend five hours or less a week reading or studying for class.94

• 65 percent of college freshmen and 56 percent of college seniors spend ten hours or less per week studying and doing homework.95

• The average full-time college student spends between twelve and fourteen hours per week studying, which is about 50 percent less time than several decades ago.96

Now take a look at the statistics for the top students I surveyed:

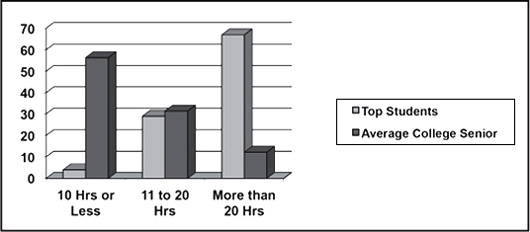

Take a look at this chart comparing how much time typical college seniors and the top students in my survey (as undergrads) spend studying and doing homework per week. (The stats for the former come from a 2009 survey of over 24,000 graduating seniors.)97 The results are rather jarring.

As you can see, the top students study a lot more than their peers. While many people in high school and college prepare for ten hours or less a week, only 20 percent of the high achievers did that in high school, and almost none did so in college. The majority studied more than 20 hours per week as undergrads, and almost everyone in this group said that hard work played a major role in their success. When asked to rate the importance of hard work on a scale of 1 to 10, 43 percent of the top students gave it a perfect 10, and 27 percent gave it a 9; this was second only to determination.

Let’s look at the issue from a broader perspective. In case you’ve been living under a rock for the last few years, you know that students in many Asian countries have been kicking our butts. For example, in the 2009 PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) test of high school students in sixty-five countries and regions, the United States came in twenty-third in science, seventeenth in reading, and thirty-first in math.

The real winners were the nations or regions of Shanghai, China; Hong Kong, China; Singapore; Japan; Korea; Taiwan; and, making a surprise appearance, the Scandinavian country of Finland. Take a look at the chart to see where each one came in. Arne Duncan, U.S. Secretary of Education, called the results “an absolute wake-up call for America.” If the U.S. is to remain competitive in the global economy, its students must catch up to their foreign peers.

Results of the 2009 PISA Test |

||

Science |

Math |

Reading |

Shanghai, China |

Shanghai, China |

Shanghai, China |

Finland |

Singapore |

Korea |

Hong Kong, China |

Hong Kong, China |

Finland |

Singapore |

Korea |

Hong Kong, China |

Japan |

Taiwan |

Singapore |

Korea |

Finland |

Canada |

… |

… |

… |

United States (23) |

United States (31) |

United States (17) |

Source: PISA 2009 at a Glance, OECD Publishing (2010), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264095298-en.

There are a lot of possible reasons for Asia’s success. It’s been attributed to cultural values, better teachers, a stronger work ethic, longer school days, shorter summer vacations, parental pressure, fiercer competition for university spots and jobs, and many other factors. In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell even links it to the labor-intensive rice-paddy economy of southern Asia.99 Probably all of these things play a role, but I want to talk about the ones you have control over. Let’s look at some stats about Asian—specifically Chinese—students. As you’ll see, it’s not just top American students who are putting in the extra time.

• Chinese students spend twice as many hours doing homework as their peers in the United States.100

• According to one survey, Chinese high school students study for an average of seventeen hours per week.101

The average Chinese student seems to study a lot more like a top student than the average American scholar. Time magazine put it bluntly in the article “Five Things the U.S. Can Learn from China” when it stated, “The Chinese understand that there is no substitute for putting in the hours and doing the work.”102 According to the Asia Society’s 2005 report on education in China, “Effort, not ability, is presumed to determine success in school.”103 In other words, what matters isn’t how naturally talented you are, but how hard you try. This is an important part of the Chinese attitude toward education, and it’s something you can apply to your own life no matter where you come from. By contrast, many American students fail to see the connection between hard work and success.104

There’s no “magic number” of hours you have to study to succeed in school, but many college professors recommend two hours of studying per every hour of class time. So according to this rule, if you’re taking five three-credit courses—where a credit represents an hour of class time—you should be studying about thirty hours a week ((3 × 2) × 5). If you’re in high school, you might want to consider each of your classes to be a two- or three-credit course.

However, I find this view a little simplistic. There are too many variables such as the difficulty of each class, how reading-intensive it is, and how fast you work. I’ve had some three-credit classes where I barely had to work at all and others which ate up nearly half my overall study time. But the rule does give you a rough idea of how much you should be doing. Not surprisingly, there’s a direct connection between how much you study and your grades. Decreasing study time by about forty minutes per day lowers GPA by an average of 0.24 points.105

Keep in mind that I am not telling you to become a hermit, locking yourself away in your room after class and memorizing your textbook. But studying ten to twenty hours a week, or even twenty to thirty hours, doesn’t seem excessive, especially when you consider that you can make up a lot of time on the weekends. If you study or do homework for two hours a day after school, you’ve got ten right there. Add in a few hours over the weekend, and you’re well on your way to twenty.

Consider devoting half your weekend to your school-work and the other half to whatever you want to do. The weekend is prime study time, since you’ve (hopefully) caught up on your sleep and won’t have as many distractions from classes and friends. Your parents—people with regular jobs—may get evenings and weekends off, but don’t try to copy their lifestyle. The sooner you accept that you’ll often have to work while the adults get playtime, the better.

Some people may be horrified by the idea of downsizing their social life, but the amount of socializing that goes on in high schools and colleges seems to be spiraling out of control. In a study examining why up to 45 percent of U.S. college students fail to improve in core academic skills—you know, just little things like critical thinking, writing, and reasoning—Arum and Roksa say that this is partly due to students’ “defin[ing] and understand[ing] their college experiences as being focused more on social than on academic development.” Students spend about one-third of their all-too-few study hours with their peers, an arrangement which is “not generally conducive to learning.”106

Being able to work by yourself is a skill that’s often overlooked, but solitude fosters independence, concentration, creativity, and original thinking. And socializing isn’t the only thing U.S. students are doing too much of: according to a 2010 report by the Kaiser Family Foundation, Americans age eighteen and younger spend an average of seven hours and thirty-eight minutes a day using entertainment media.107 If students are able to devote nearly half their waking hours to watching TV, listening to music, playing video games, sending texts, and surfing the Web, they have little excuse for not hitting the books more.

Some students say they’re too busy with jobs or extracurriculars to devote more time to their studies. It is important to do stuff outside of school, both for your sanity and for your resumé. But you should also ask yourself whether you’ve bitten off more than you can chew. It’s no secret that students have become chronically overscheduled, jumping from activity to activity, often at the expense of their schoolwork.

Only you can decide how important these activities are. Keep in mind that, in the case of extracurriculars, quality is more important than quantity. It’s usually better to excel at one or two things—for example, to get really good at a sport or an instrument, or to become president of a club—than to superficially engage in lots of activities just so you can pad your applications.

If you’re doing a menial job for a little extra spending money, can you cut your expenses so you could work fewer hours? Also ask yourself, is it really the job and extracurriculars that are causing you to study less than you should? Or is it actually a combination of other, less vital activities? According to Babcock and Marks, students appear to have reduced studying by 50 percent over the last few decades to have more leisure time, not to do more paid work or extracurriculars.108 Something to think about.

Think fast—how many hours a week do you spend watching TV? How about studying and doing homework? Not so easy, is it? Most of us have only a vague idea of where our time goes, so here’s an awareness exercise for you to complete over one week. In the space on the following pages, write down how many hours you spend on the given activities each day. Note that you should pick a typical school week, not during finals or summer vacation.

Tip: Most top students spend more than ten hours a week studying and doing homework in high school, and more than twenty hours a week in college. If you’re spending much less time than this, you might want to cut back on some nonessential activities.

Attending class: ___

Studying/Doing homework: ___

Extracurriculars/Job/Internship: ___

Commuting: ___

Exercising: ___

Chores/Family responsibilities: ___

Socializing (Dates/Parties/Hanging out): ___

Entertainment (TV/Games/Web/Movies/Shows): ___

Sleeping: ___

Other: ___

Attending class: ___

Studying/Doing homework: ___

Extracurriculars/Job/Internship: ___

Commuting: ___

Exercising: ___

Chores/Family responsibilities: ___

Socializing (Dates/Parties/Hanging out): ___

Entertainment (TV/Games/Web/Movies/Shows): ___

Sleeping: ___

Other: ___

Attending class: ___

Studying/Doing homework: ___

Extracurriculars/Job/Internship: ___

Commuting: ___

Exercising: ___

Chores/Family responsibilities: ___

Socializing (Dates/Parties/Hanging out): ___

Entertainment (TV/Games/Web/Movies/Shows): ___

Sleeping: ___

Other: ___

Attending class: ___

Studying/Doing homework: ___

Extracurriculars/Job/Internship: ___

Commuting: ___

Chores/Family responsibilities: ___

Socializing (Dates/Parties/Hanging out): ___

Entertainment (TV/Games/Web/Movies/Shows): ___

Sleeping: ___

Other: ___

Attending class: ___

Studying/Doing homework: ___

Extracurriculars/Job/Internship: ___

Commuting: ___

Exercising: ___

Chores/Family responsibilities: ___

Socializing (Dates/Parties/Hanging out): ___

Entertainment (TV/Games/Web/Movies/Shows): ___

Sleeping: ___

Other: ___

Yes, you must include weekends, too!

Attending class: ___

Studying/Doing homework: ___

Extracurriculars/Job/Internship: ___

Commuting: ___

Exercising: ___

Chores/Family responsibilities: ___

Socializing (Dates/Parties/Hanging out): ___

Entertainment (TV/Games/Web/Movies/Shows): ___

Sleeping: ___

Other: ___

Attending class: ___

Studying/Doing homework: ___

Extracurriculars/Job/Internship: ___

Commuting: ___

Chores/Family responsibilities: ___

Socializing (Dates/Parties/Hanging out): ___

Entertainment (TV/Games/Web/Movies/Shows): ___

Sleeping: ___

Other: ___