In most towns, cities, and developments, water is moved off the land as quickly as possible. Although it’s critical to control flooding, when water is quickly funneled into rivers and streams without first infiltrating the ground, it can cause rivers to rise quickly and flood downstream areas, decrease groundwater levels, and begin a cycle of stream channel erosion.

To make sure we have enough clean drinking and irrigation water, and to keep the force of water from eroding the landscape, permaculture has a simple mantra: “Slow it, spread it, sink it”— that is, catch the water, hold it on-site, and get the water back into the ground. In the process of catching and distributing the water, we hold it in catchments like ponds, tanks, cisterns, and swales and use it (for growing food, irrigation, drinking, and so on) before it infiltrates the ground. There are a few ways to do this.

Store water in soil. Soil is by far the largest reservoir of water on the landscape, and given the choices of water storage, increasing the soil’s water-holding capacity is the cheapest option. Soil that is deep, friable (open and loose, not compacted), and high in organic matter (full of broken-down and decomposed plants and animals) will hold large amounts of water. We can increase water storage in the ground in a number of ways: by building up the level of organic matter in the soil, which improves its ability to hold water; by increasing the amount of vegetation on the land; and by creating earthworks, like swales and basins, that can increase infiltration and recharge the shallow groundwater.

Store water in vegetation. Thick vegetation can hold large quantities of water in several ways. When rain falls into an area with lots of plants, some of the water is held by the leaves and branches, and some is held in the low-growing vegetation close to the ground. (Think about walking out across a field or lawn after a storm. Even when the air has dried, there is quite a bit of moisture in the grass you’re walking through.) Some of this water is slowly released into the soil; some evaporates back into the air. Water is also stored in the living biomass of the plants (which are 90 percent water by weight). In thick vegetation, this amounts to a large reservoir of water.

Store water in the ground. Small catchments, such as swales and basins, are very effective for catching water and helping it infiltrate the ground, especially if the landscape is designed to slow the water, preventing it from gaining volume or speed as it moves downhill. Small basins can catch and hold water at individual plants or plant groupings; organic mulch, like wood chips in a basin, hold the water and give it time to soak in. Start by going “upstream” to identify the sources of water coming onto the land, and then look for ways to hold the water and let it percolate into the soil. In urban areas, this might mean looking at building roofs as places to intercept and direct the water. Identifying leverage points and intercepting the water early in its flow can have a large net effect.

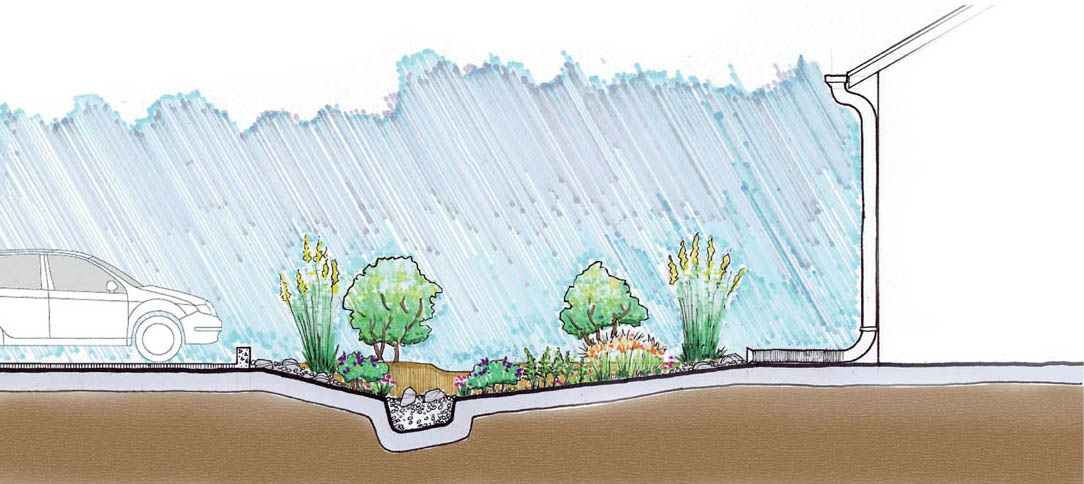

Rain gardens capture rainwater runoff and keep it in the soil. Channeling the water and using appropriate plants that can tolerate periodic flooding are key to the garden’s success.

There are several ways to slow the flow of water and hold it in a landscape, so that it has time to infiltrate the soil and recharge groundwater, and to avoid soil erosion.

Infiltration swale. A shallow trench dug across a slope, on contour, to intercept the flow of water and give it time to infiltrate the ground.

Berm and basin. A smaller infiltration basin on a slope with a corresponding berm downslope. Not as linear as a swale.

Fish-scale swale. A small, miniswale or minibasin set up as overlapping basins to catch the overflow of the basin above, thus the fish-scale reference. Usually used where larger swales cannot be installed or where water catchment in many small locations is preferred, such as at multiple tree locations.

Conveyance swale. A shallow trench or channel, dug slightly off contour, to catch and direct the flow of water. The steeper it is, however, the faster the water moves, reducing water infiltration. Water bars are a conveyance swale to take water off a road and into some other structure, such as a rain garden or infiltration basin. Check dams (small dams in a stream or swale) can slow water movement for better infiltration and to even out varying flow levels. When a conveyance swale is filled with vegetation, it is sometimes referred to as “vegetated swale” or “bioswale.”

Rain garden. A small to large basin filled with plants that tolerate sporadically wet conditions. Rain gardens catch and hold water and allow it to infiltrate the soil, and they can be used in any type of landscape, whether residential, commercial, or urban.

Detention/retention basin. A basin meant to hold and slowly release stormwater in an effort to reduce flooding and extreme flows into streams from highly developed areas. Retention basins catch and hold water; detention basins catch and slowly release water, drying out between storms.

Terrace. A flat planting bed on a slope that can also act as a water catchment site, slowing water and encouraging it to infiltrate the soil. Increases access and planting space as well.

Fascine, log-terrace, or log-erosion barrier. Logs or bundles of sticks (fascines) staked across slopes or set into shallow cross-slope trenches. These small barriers slow water and catch sediment. Over time they can form stable microswales.

Strip cropping, living dams. Rows of perennials planted on contour can catch and hold water as well as any moving nutrients or sediment. Plants that produce a lot of biomass can hold slopes and also be used as mulch (like switchgrass in a temperate zone and vetiver grass in the tropics). Strip cropping with alternating rows of hay or seed and tillage crops like corn or beans can also catch and hold water and reduce erosion.

Village Homes, an ecologically designed community in Davis, California, was almost never built. The process of getting the development plans approved by local government was difficult and contentious, mostly because of its innovative stormwater management plan, which was designed to keep as much water as possible on-site. The system called for moving water away from the homes and toward central open drainage channels to allow the water to infiltrate the soil. Excess water would flow into larger basins and catchments around the property as needed, depending on the volume of rainfall.

At a time when building requirements called for getting stormwater into pipes and off-site as quickly as possible, this design was controversial. The town engineer, dubious of the “radical” system, suggested declining the permit application. Fortunately, the town permitting board allowed the first phase to go ahead as planned— with the requirement that the developers post a bond to cover any costs that might result if the water system failed and caused flooding into neighboring developments.

During construction of the first phase, there happened to be some periods of intense rain, and several local areas flooded. However, the Village Homes system operated as designed, allowing stormwater to infiltrate on-site, and it even absorbed stormwater that had backed up from neighboring developments. After this successful showing, the town lifted the bond requirement for successive phases of the development project.

At a time when most housing developments funneled stormwater into the town sewer system, the Village Homes community was designed with a network of drainage channels to keep stormwater on-site and allow it to infiltrate back into the soil.

A stormwater retention basin becomes an outdoor amphitheater during dry times.