Water is essential for all life on earth. Although it covers 71 percent of the earth’s surface, there is a limited supply of fresh water, which exists primarily in the ground (groundwater), but also in streams and lakes. Only 3 percent of water on the planet is freshwater, and a mere 0.03 percent is not in glaciers or deep groundwater. Whether you live in the drought-stricken West or in a region that experiences unpredictable rainfall, you know what a precious resource freshwater is.

Threats to our limited freshwater are largely from overuse and pollution. Groundwater levels are dropping; many water bodies are contaminated with nutrients, sediment, or toxic compounds. The future of our water supply is uncertain, and planning for our water needs should be a top priority. The ethics of permaculture — care for the earth and care for people — indicate that we should use water thoughtfully and leave the water cleaner than when it arrives to us. The ethic of fair share asks us to limit our consumption, in order to leave enough water for others. There are many ways to use less water, keep it clean, and collect the water we need for our personal and community uses.

An astounding volume of rain falls from the sky, even in areas with low rainfall amounts. For example, a 0.2-inch rainfall (a mild storm) on 1,000 square feet of ground amounts to 125 gallons of water. This rainwater is a resource just asking to be caught and stored for use in irrigation and as drinking water.

The easiest way to capture rainwater is to collect what falls off a roof. Metal roofs, though expensive, are best suited to this type of use (after tile or slate, which are even more expensive) because they don’t release petroleum compounds into the water.

Knowing how much rain falls in your area every month, and how much roof area you have, can help you gauge your rainwater harvesting potential. Even a small surface, like a shed or back porch roof, can collect large amounts of rainwater through a season. My family collects rainwater for our chickens simply by putting a bucket under a low corner of the mobile chicken coop roof; this way, we don’t need to carry water to the coop as it moves around the land.

Rainwater collected off a building roof is commonly stored in a tank or cistern. Although the tanks themselves, or materials to build a cistern, can be expensive, consider it an investment in resilience. There are many shapes, sizes, and types of tanks that can fit in different sites and conditions. Rainwater barrels that hold 40 to 55 gallons are now relatively common. They are a good start and are usable on a small scale, but once your irrigation needs go beyond 55 to 110 gallons (which can happen quickly), you’ll need to increase your water storage capacity. A tank that holds 300 gallons can get a small orchard through a brief drought; it’s enough to give 20 trees 5 gallons each per week, over a three-week dry period.

Some tanks are designed to be set belowground. Buried tanks take up less land space and aren’t a visual distraction, and depending on how deep they’re set and the weather conditions, they can protect their contents from freezing. Whatever type of tank (or any water storage container) you have, set it as high up as possible, so that you can use gravity to draw water from it, without the need for pumps.

In addition to collecting water, we can limit how much we use. We can easily take steps like installing low-flow showerheads and faucets, taking shorter showers, and using an energy-efficient dishwasher instead of washing by hand. We can also address the fixture that accounts for almost 27 percent of household water use — the toilet.

Most people use a flush toilet without giving a thought to the clean water used in the process and the contamination that ensues as the waste seeps into the ground or is “treated” by water treatment plants and then flows into a nearby waterway or back into the water supply. Even a “low-flush” toilet uses 1.6 gallons per flush; using the toilet five times per day means each person is pumping and flushing 2,920 gallons of water each year. A family of four in the house may be using as much as 11,680 gallons per year just flushing the toilet. A “regular” toilet (not low-flush) uses twice as much.

The alternative to the flush toilet is a composting toilet. Some people might picture a composting toilet as a smelly outhouse in the woods, but we’ve come a long way since then. There are many efficient, clean ways to compost our “humanure.” Systems can be simple owner-built setups or commercial units. At my home, our composting toilet is a large-batch Phoenix-brand composting toilet. After every use, we toss in a handful of wood shavings. The pile is mixed weekly with several aerating tines, and every two years we remove 20 to 30 gallons of rich, earthy compost, turning what would have been a waste product into a resource.

A popular way to compost humanure that I’ve used in the past is the bucket system outlined by Joe Jenkins in his Humanure Handbook. This is a simple, effective way to compost waste, but it requires more handling than is ideal for many people. Small batches are collected in a 5-gallon bucket and then transferred to a larger, dedicated compost pile. For larger households and for long-term use, an in-place batch composter is probably better.

Using rain barrels to capture water for irrigation is a simple way to cut down on groundwater usage.

Even a “low-flush” toilet uses 1.6 gallons per flush; using the toilet five times per day means each person is pumping and flushing 2,920 gallons of water each year.

Gap Mountain Permaculture in Jaffrey, New Hampshire, is the homestead of designer Doug Clayton. The water system at Gap Mountain comprises several integrated elements that work together to collect, hold, and cycle the water falling on and flowing over the land. Doug created this water system at his home to make the best use of water in a very low-energy system.

Rainwater is collected off the metal roof via gutters and downspouts and then is funneled down into a basement cistern. This concrete cistern, which forms part of the basement foundation, holds 3,400 gallons of water for use in irrigation and for in-home water needs. The cistern is built into the ground so that its contents won’t freeze in the bitter New Hampshire winters.

Overflow from the cistern gravity-feeds into a pond downslope of the house. The pond is sealed with a layer of bentonite clay, so that the sandy, gravelly soil here can hold the water. The water of the pond and nearby large stones hold heat and create a warm microclimate, which is ideal not just for pond-side plants but also for people; it’s a beautiful spot to relax. The pond also allows some water to infiltrate the soil and recharge the groundwater and support nearby plantings.

Overflow from the pond moves through a small spillway that directs the water down the slope and into the orchard below. Water flowing into the orchard infiltrates the ground, recharging the groundwater and making it available for the fruit trees and associated plants.

In addition, a shallow well in the orchard provides access to this groundwater, and during a drought period, a solar-powered pump cycles water back up to the cistern at the house. With these three main gravity-fed storages — the cistern, the pond, and the soil — and a solar-powered pump, the water stays on-site and makes a complete cycle through the property.

In addition to the rainwater harvesting and cycling, Doug has a composting toilet for the solid “waste” and a graywater system for the water from sinks, shower, and laundry. The graywater flows into a 70-gallon tank inside the attached greenhouse. When the tank is full, it empties in one surge, forced by gravity, into piping that irrigates a garden bed below the house. That garden bed is filled with wood chips and planted with raspberries. The wood chips host soil organisms that take up the nutrients in the graywater, passing them to the raspberry plants. As the wood chips decompose into soil, they are replaced with fresh chips. And any detrimental organisms in the graywater become part of the food chain when they enter the soil.

The composting toilet, a design that Doug and permaculturist Dave Jacke developed (called the Gap Mountain mouldering toilet), composts the humanure in two adjacent bins used in succession. While one bin rests and its contents break down into rich earth, the other is in active use as the toilet. The bins hold solid human waste and urine as well as wood shavings or other bulk material.

There are many easy water-saving techniques we can incorporate into our daily lives. If we take it a step further and evaluate how we design the systems that support us, we can have an even bigger effect.

A composting toilet can save thousands of gallons of water each year.

Collecting and distributing graywater (the water from washing machines and the kitchen sink) to irrigate gardens is a good way to use water more than once.

With surface irrigation (like a sprinkler system), a portion of the water delivered is lost to evaporation; subterranean irrigation avoids this and keeps water in the ground.

When we built an addition onto our house, we incorporated a cistern into the poured foundation to capture and store rainwater.

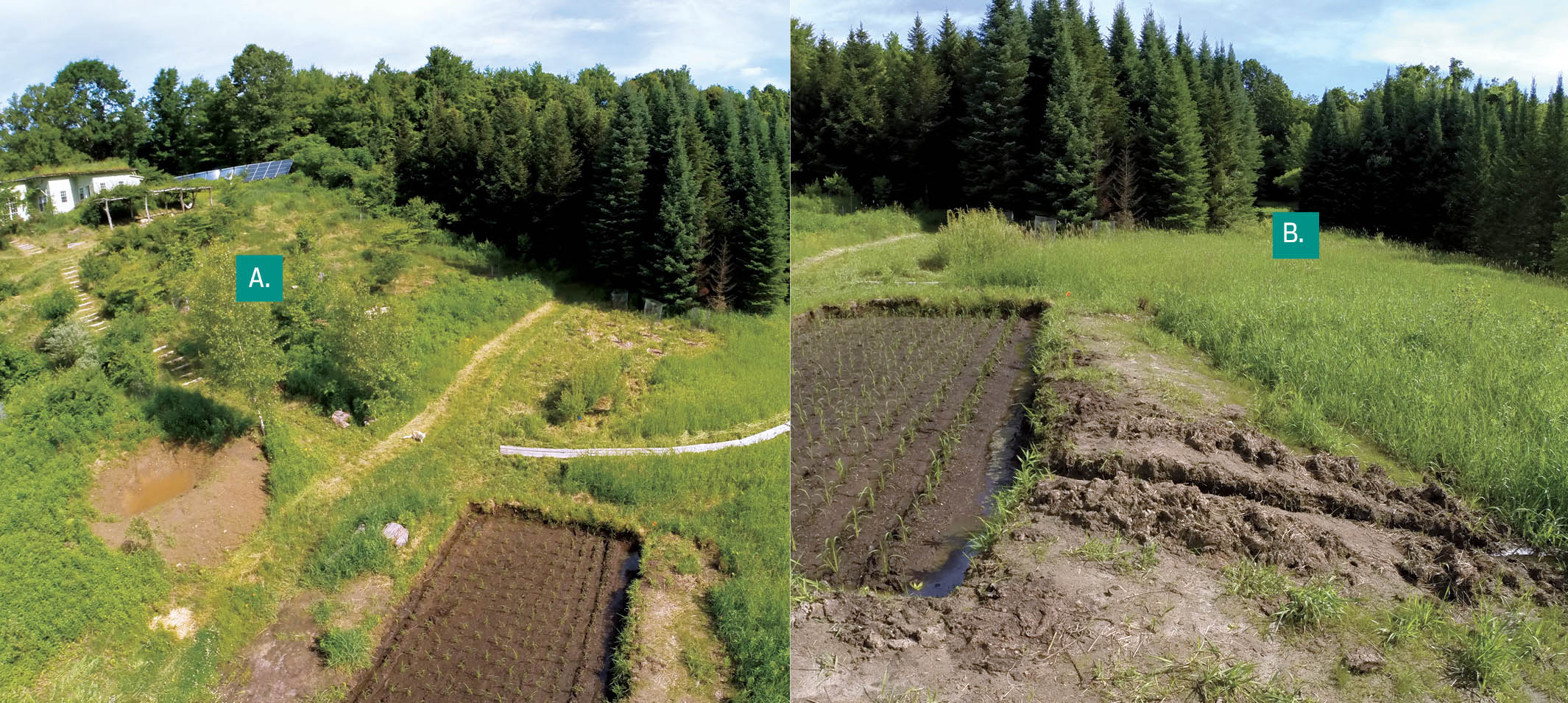

For the last five years, my design firm, Regenerative Design Group, has been developing an example of integrated permaculture design on an 8-acre rural homestead in Conway, Massachusetts: Wildside Gardens. It is stewarded by owner, resident, and caretaker Sue Bridge, and it contains all the elements of a fully functioning system: a small, energy-efficient, off-grid cottage with energy systems, greenhouse, root cellar, and green roof. It also includes production gardens, kitchen gardens, an orchard, a forest garden, a rice paddy, and surrounding habitats that are utilized for less-intense production.

I entered the process as the home was being built. After interviewing Sue about her intentions and spending almost a year observing the land and its patterns amid the ongoing construction, we came up with a whole-site plan. Much of the initial pattern of the site planning has remained as we designed it. But, as is the case with any design project, there have been changes as we’ve come to know the land better and as we’ve refined the project goals.

The arbor is made of black locust, a rot-resistant, locally grown wood. In the background, the cottage produces its own electricity and hot water with the solar electric and hot water system, making it independent of the energy grid.

An inviting path leads through the forest garden and creates access on the steep slope.

The green roof cottage at Wildside is positioned on a south-facing slope — perfect for active and passive solar. The green roof insulates the roof and lengthens its life span. Gardens wrap around the cottage to the south for easy harvesting access and the solar hot water and electric systems are positioned out of the way to the north of the cottage.

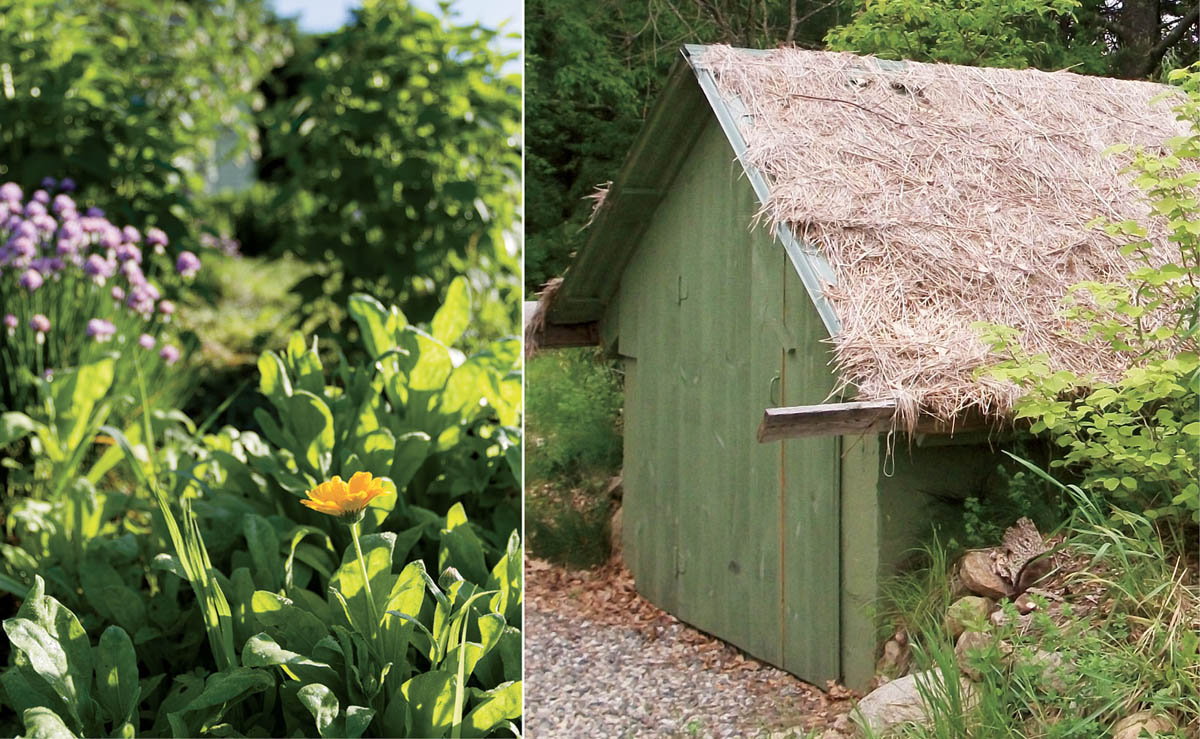

Left: Perennials such as chives and calendula attract and feed pollinators, and can be harvested for medicine and food.

Right: The root cellar at Wildside (built into the hillside to utilize the relatively constant temperature of the earth) stores root crops and winter vegetables for use through winter and spring.

The homestead is a place of learning and experimentation, and a way to document the development of a full permaculture-designed homestead. As such, it’s become a destination for groups and classes. Sue thinks of this as an early-twenty-first-century work-in-progress, to get ready for the “new normal”: a world affected by the effects of climate change.

The different areas of the Wildside Cottage and Gardens are:

Wildside Gardens is a place of study and learning as well as production. Here, Keith Zaltzberg of Regenerative Design Group leads visitors through the forest garden.

The production gardens and earth-bermed greenhouse with a green roof allow for almost year-round production and supply a sizable amount of Sue’s food. In the summer the greenhouse has heat-loving crops like ginger, sweet potatoes, and fig.

Turkish rocket is a perennial vegetable, producing yearly crops of broccoli-flower heads and edible leaves. The flowers support myriad pollinators.