RUE BONAPARTE

…of which the north part between the Seine and the Rue Jacob was called chemin de la Petite-Seine (1368), de la Noue (1523), Rue des Petits-Augustins (XVIIth c.);—the central part between the Rue Jacob and the boulevard St. Germain, open on the ancient abbey, was called Cour des Religieux (1804), Rue Bonaparte (1810)…

Rochegude et Dumolin, GUIDE PRACTIQUE À TRAVERS LE VIEUX PARIS

My husband John and I have lived on Rue Bonaparte next to the chapel for about four years now, for six or so months of every year. Paris comes to feel more and more like home, while our place in San Francisco seems farther and farther away. In Paris, we are a step or two away from the Louvre, the Institut de France, the Pont Neuf, and other iconic structures in this precious, actually rather small, city.

Rue Bonaparte begins on the Quai Malaquais, on the Left Bank of the Seine, across from the Louvre. Parisians make a sharp distinction between the Left and Right Banks of the Seine (by which they mean the south and north banks), but the visitor has the luxury of ignoring this age-old distinction—the legacy of days when the river had to be crossed by ferry—which attributes staid respectability to the Right Bank, and an aura of artiness to the Left. The area is a harmonious ensemble, the work of centuries, but especially of the seventeenth century, the epoch that has most distinctly shaped the whole sixth arrondissement. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and even modern Paris, are also represented within a few minutes’ walk, the latter by the new Solférino bridge, a lovely arc linking the Left Bank with the Tuileries, across from the refurbished train station, Gare—now Musée—d’Orsay, a museum for the art of the nineteenth century. The Orsay includes the amazing painting by Courbet, “L’origine du monde,” of a hairy vagina and two plump thighs; the eagerness to see this curiosity, I’m told, in part explains the long lines always waiting outside the museum to buy tickets.

Rue Bonaparte, author’s home

And there are vestiges of Roman Paris and medieval Paris within a few minutes’ walk. If you go into the parking garage on the Rue Mazarine and walk down one level, you will see a formidable wall, perhaps twenty feet high and six or eight feet thick, of gray stones, part of the wall built by King Philippe-Auguste in 1200 to encircle Paris. Archaeologists must know, but I have never understood, how civilizations sink. They are always covered over by subsequent civilizations, but mustn’t they have sunk first, as if the core of the Earth were shrinking, drawing everything down? Or do they rise, thickening the Earth as they acrete layer upon layer of city? It is always hard to visualize.

A few words by way of orientation for anyone who plans walking around. Part of the pleasure of living in Paris is the pleasure of discoveries impossible when you’re separated from the world by a car. From Rue Bonaparte I can walk almost anywhere in Paris, and certainly everywhere I need to go. If you want to get there faster, or in bad weather, there are the Métro and the buses, and there is Paris by Arrondissements, a little booklet of maps that show every street in every arrondissement. You get it at any newsstand—much easier than unfolding a big map—and with this indispensable, and a packet of bus/Métro tickets, or better yet a weekly pass, you can never be lost.

Nor are you in danger, except from pickpockets. It is sometimes hard for visitors to internalize the paradox—having both the carefree feeling that personal safety gives you, and the need to keep your purse and pockets zipped up. I’m both careful and wary, but I do travel a lot, and have been pickpocketed or had things stolen, out of bags, from under the X-ray screener, in a store, five times, always in France. The skill of the pickpockets defies belief. The last time, getting off the bus at my own bus stop, I was so exasperated I confronted the thief and demanded my wallet back. To both our surprise, he gave it to me, without a word, but with a look of fear on his face. Perhaps he (correctly) saw in mine the look of a woman who was going to raise a big, audible fuss.

Say you are standing in the courtyard of the Louvre, the great palace, along with its gardens the Tuileries, that dominates the Right Bank of central Paris (and which any taxi can find). Stand with your back to the Pyramid—the amazing glass structure designed by I. M. Pei when François Mitterand was president. (Mitterand was not the only French president who wanted to change the face of Paris. Luckily most of them have been deterred. One hears that Georges Pompidou, who did place the Centre Pompidou, an amazing modern structure on the site of the old market area, also wanted freeways along the Right and Left Banks. This would have meant tearing down much of historic Paris, rather as Baron Haussmann did in the nineteenth century for Napoleon III, to build the large, handsome Right Bank apartments we think of today as being so typically Parisian.)

Anyway, you are facing the Tuileries. From this spot, you turn left and walk toward the river on the street that runs through the middle of the Louvre, cross the bridge (Pont de Carousel), a wide structure guarded by four female figures, whether queens, goddesses, or muses I am not sure. When you get to the Left Bank turn left on the Quai Malaquais. Walk eastward, crossing the Rue des Sts.-Pères, and continue along the Quai Malaquais past the École des Beaux-Arts museum, a large, classical nineteenth-century building fronting the quay to the next street, which will be Rue Bonaparte. It will take no more than ten minutes to walk from the Louvre to Rue Bonaparte.

On this short stretch of the Quai Malaquais, by the way, the buildings, except for the museum, were built about the time that d’Artagnan came to Paris, in the 1630s. Number seventeen, now part of the École des Beaux-Arts, was formerly Hôtel de la Bazinière, or Chimay, whose beautiful doors are classées, that is, on a list of valued buildings or parts of buildings that cannot be changed. We have a friend to whose family this palais belonged in former centuries, but I don’t know if it was the Revolution or the persecution of Huguenots that deprived them of it.

The name Malaquais came from mal acquis, or wrongly acquired, no one knows by whom or why, and the stretch of it between Bonaparte and the Rue des Sts.-Pères was called Escorcherie aux Chevaux. The meaning is unclear—I haven’t found the word escorcherie in my French dictionary, the closest being escorter, to escort. The street names of Paris have often changed when a new or better name came along, and the changes always tell a story. Recently the Quai du Louvre on the Right Bank was changed to Quai François Mitterand after the late president.

As in one of those puzzles where the eye must discern the shapes of cats or Indians from among the patterns in a drawing of draperies or foliage, so do the seventeenth-century houses emerge from the jumble of subsequent construction in St.-Germain, once you start looking for them, for though the quarter is vibrant with modern activities, its characteristic buildings are from the 1600s, and still form the infrastructure of everyday life. The spirit of St.-Germain somehow began with these, and once you are conscious of them, they form the visual matrix as well as the physical foundation, and account for the beauty of the quarter. Here they still are, built around and onto and in front of, but still serviceable and sound, with their gables and pitched roofs, elegant mansards, handsome eaves, and imposing gateways.

Among things Italianate that came with Catherine de Médicis and others in the mid-sixteenth century were architectural principles that influenced the style of most of the great châteaux and palaces of France. The seventeenth-century “hotels” in this neighborhood are classically symmetrical L- or U-shaped buildings set in courtyards, shut off from the street by a wall and gate or by a fourth wall of rooms closing the space so that the courtyard is completely interior, reached by a large street door and wide passage through the streetside building to the court. When the visitor walks along a Paris street he sees a solid facade of buildings with wide, thick oak doors that require numeric codes to be typed in before they will open. He should remember that behind these somber facades are delightful courtyards and gardens, and windows looking down on them as well as onto the street.

Sometimes the garden spaces are enormous—one such garden nearby at 176 Boulevard St.-Germain (serving partly as a parking lot) can be seen by anyone during the day and gives a good idea of what is often behind the solemn facades. Some of the gardens here and in the seventh arrondissement, belonging to the huge private seventeenth-century palaces, have now been turned into embassies or government buildings, and if you happen to be in Paris on the right weekend in September, all the great private gardens of these buildings, usually hidden, are thrown open to the public. On a subsequent weekend, it is the palaces themselves to be opened, and people stand in line from early morning to get a glimpse of the remarkable interiors and treasures of furniture and paintings inside, where they are enjoyed by government officials in private the rest of the year.

The gates that wall and close the courtyards are usually high and imposing, large enough for carriages to enter, and sometimes flanked by a single door for entrance by people on foot. (One can’t help but think of La Door, the name a witty architectural historian has given to a sort of pretentious door found in fancy Los Angeles houses; the criterion is that La Door rises higher than the eaves, as these seventeenth-century gates do.) These were palaces designed to announce the wealth, piety, and power of their owners, with vast reception rooms for public entertaining, and smaller, more intimate, apartments above—and with gardens where possible.

The main rooms are on the first floor, that is, to Americans the second floor, or one floor up from street level. These have wooden parquet or stone floors, high ceilings, and tall windows almost to the ceilings, closed by interior shutters or volets; the remaining two (usually) floors will have lower ceilings, and on the top floor, the low, small rooms are where the servants lived. Since the invention of the elevator, these rooms have developed considerable prestige, for they are sunny and cozy, and now considered chic. As a result, it’s Americans and other foreigners who are consigned to live in the fancy étages nobles, apartments unwanted by the French and rented out.

Then, as now, all was and is not grandeur in St. Germain-des-Prés. On the Rue Visconti, “little Geneva,” named after the main center of Protestant thought in Switzerland, runs between Bonaparte and the Rue de Seine. Racine died in 1699 in reduced circumstances at number twenty-four; and Balzac would later have his printing business at number seventeen. These are rather homely buildings, mostly plain-faced stucco over the stone walls, smaller windows shuttered on the outside, with grilles of wrought iron across their lower panes. Throughout the whole of this “historic” area, the city of Paris strictly ordains the color each building is to be painted—no frivolities of rose or blue permitted. Modest expressiveness is allowed in choosing the color of the massive double doors, sometimes painted blue or left in natural wood, like the doors from the château Anet now stuck onto the Église des Petits-Augustins—but the choice for most doors is, overwhelmingly, dark, shiny green.

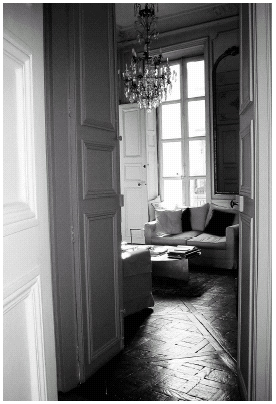

Interior of the author’s apartment

We, like other foreigners, live on the first floor. At Bonaparte, turn right, and our building is a few doors along on the right, facing number five, which has a battery of plaques announcing that Maréchal Lyautey lived there, and that Edouard Manet was born there in 1832. In four hundred years, any building will have had a lot of residents, its seedy patches and its glorious ones, but number five has had more than its share: The French biographer Henri Troyat lived there until recently; and a friend who grew up in it says that the rumor among its occupants was that Napoleon’s mother did, too, as well as Napoleon’s sister, the frisky Pauline Borghese.

Typical courtyard of the sixth arrondissement

Josephine herself lived at 1 Rue Bonaparte with her first husband, Count Beauharnais, who later was beheaded in the Revolution; the street, naturally, wasn’t called Rue Bonaparte before Napoleon’s time, but Rue des Petits-Augustins. The star of number five has risen these days, as it is partly owned by Pierre Bergé, patron of the arts and founder of the empire of Yves St. Laurent. My friend Monsieur B. says that Bergé, when he wasn’t permitted to raise the ceiling of his very grand ground floor apartment, could not be impeded from lowering the floor—but he couldn’t confirm this story.

Picture this same Rue Bonaparte at the beginning of the seventeenth century, or still earlier, when it was not a street but a canal, la Petite Seine. The present Rue de Seine was la Grande Seine. Sometime around 1540, la Petite Seine was filled in, and became the Rue des Augustins, or Petits-Augustins, referring to the Augustinian convent being built there, set in the middle of a field, or pré. In this field, students from the medieval university used to disport themselves, doing whatever they did, apparently mostly quarrel and fight. A lot of dueling, which seemed to have been the principal activity of the Three Musketeers, went on in this field, and it was here, I was sorry to learn, that the real-life counterpart of Athos, my favorite of the Musketeers, met his real-life end in a duel.