I. INTRODUCTION: MUTUAL DISSATISFACTION

Alejandro Amenábar flunked out of film school. Today his sanitised biography in the US college textbook Cinema for Spanish Conversation says he left because he was not being challenged by the curriculum (McVey Gill et al. 2006: 260). But Amenábar was bitter as a student. He definitely held a grudge against the professor who failed him in his screenwriting class. In his successful debut film Tesis (Thesis, 1996), Amenábar took his revenge by parodying his nemesis through the character of Professor Castro (Xabier Elorriaga). Although Castro speaks the ‘dirty’ truth about the abysmal state of Spanish cinema in the 1990s in the global market, he is not only pompous and self-absorbed, but also an accomplice to murder. To say the least, this professor makes a scary thesis adviser for the protagonist Angela (Ana Torrent).

There is a spirit of rebellion against authority, and in particular, against father figures, in all of Amenábar’s films. To state this solely in terms of Amenábar’s personality is to engage in pop psychology; nonetheless, it can also serve as a metaphorical guide for exploring his career strategy within the industry and for defining the zeitgeist in which his films first appeared. Our ultimate goal is to interpret the films themselves within their cultural context. This chapter will explore how Amenabár built his career against Hitchcock; each of Amenábar’s first four films took Hitchcock’s classics as models of inspiration to work, or rebel, against. Amenábar adapts Hitchcock’s films to show and correct the errors Hitchcock made in them. For him, the anxiety of influence, to cite Harold Bloom’s eponymous text (1996), has always been a matter of rebelling against the father, or certainly against the ‘strong’ father’s work.1 Of all the directors whose work is considered in this book, Amenábar is the one for whom psychoanalysis and dreamwork play the most prevalent role in his films.

II. AMENÁBAR’S EARLY EDUCATION

Alejandro Amenábar was born in 1972 in Chile to a Chilean father and a Spanish mother. They came to Spain in 1973 days before the fall of Allende. According to Carlos F. Heredero, they did not flee Chile because they feared direct political repression for their beliefs, but rather because the turmoil reminded his mother of the upheavals of the Spanish Civil War (1997: 80). Ironically they now sought a more tranquil environment in Spain as that country anticipated the uncharted post-Franco era. Speaking of his own generation, Amenábar called himself apolitical, as did Almodóvar early in his career (Heredero 1997: 95). Almodóvar famously denied the relevance of Franco. He did, however, acknowledge the dictator’s impact on his decade of Catholic private schooling in which ‘se respiraba una especie de regustillo nostálgico por la época anterior’ (‘one breathed a kind of little nostalgic aftertaste for the earlier era’) (Heredero 1997: 87).

Amenábar’s early cinematic education came primarily through seeing movies on video with his neighbours, an American couple who were friends of his parents. Passionate about music as a youth, he played guitar and organ. He wrote short stories that he illustrated and set to music. Despite having no formal musical training, Amenábar is unique among Spanish filmmakers in that he composes major parts of the scores to his films himself using a computer programme connected to an organ. As a work method he often imagines the music for a scene before writing the dialogue.

Another youthful passion was his voracious reading of all of Agatha Christie’s novels. In high school as he began to see horror movies at the Cine Covadonga in Madrid and read the film magazine Fotogramas; he developed a taste for ‘cine que da miedo, no el que da asco’ (‘movies that inspire fear, not revulsion’) (Heredero 1997: 86). Since a career in the film industry seemed a natural match for someone with his interests, he enrolled in the Facultad de Cinematografía e Información in Madrid. While there Amenábar met Mateo Gil, another student and important future collaborator with whom he would co-write his first two feature films. Together they began to film shorts not connected to their assignments with a video camera. These early short films, La cabeza (The Head, 1991), Himenóptero (Himenopterus, 1992) and Luna (1994), explored the link between violence and voyeurism later developed in Thesis.2 The short films caught the attention of the Spanish filmmaker José Luis Cuerda, whom Amenábar calls ‘mi padre cinematográfico’ (‘my film father’) (Heredero 1997: 99) for giving him his first big break. Thesis was a double debut: Amenábar’s first feature film and Cuerda’s first attempt at producing.

III. THESIS : THE LESSONS OF HITCHCOCK’S COMMERCIAL CINEMA AND THE HUMOROUS IRONIES OF PSYCHO

The great irony of Amenábar’s career, given that he did not finish film school, is that his debut film has become the model, literally a textbook case for film school aspirants, of how to succeed in filmmaking in Spain. A study of his career began a series of ‘how-to’ books called Cómo hacer cine (‘How to make movies’). The first volume contains extensive interviews from all the major partners in this production. The tone of almost all of the exchanges is direct, what one could call ‘no nonsense’.3

Although Amenábar was, by 2002, the model in Spain for independent filmmaking, at the time he made Thesis he was taking his lessons from Hitchcock, all the while deflecting attention from the connection with false leads. For the Espejo de miradas interview Carlos Heredero probes Amenábar with the question, ‘Is it true that some shots were taken directly from a film called The Changeling? It caught my attention that you’d be referring to that movie, and not to some other film of Hitchcock…’ To which Amenábar responds:

Yes, in fact. It’s a movie that’s foremost in my mind because I think it communicates really well what I mean by suspense, by horror. It plays a lot with sound. How it uses music has influenced me not only in Thesis, but also in my shorts. (Heredero 1997: 103)

Amenábar goes on to comment that he also was influenced by The Night of the Hunter (1955), The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) and JFK (1991), but deflects any implication that Hitchcock was his model. He hides the influence of Hitchcock, yet it is strongly present in Thesis and in the shaping of his career, both in direct allusions and in broad terms of genre definition.

The attraction for Hitchcock is explained in part in Professor Castro’s remarks. Spanish cinema of the 1990s was not commercial enough. Amenábar saw Hitchcock, who was so often criticised for being too commercial, as a way out of this dilemma, a way to find new audiences against the Hollywood juggernaut.

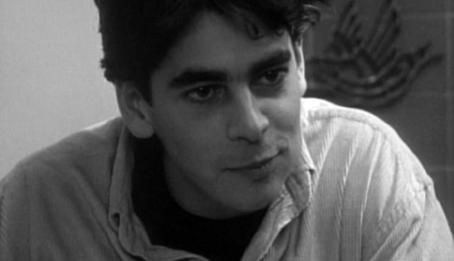

According to Amenábar’s comments in the ‘Making Of’ feature on the DVD, he intentionally chose to make a genre film with Thesis because its more ‘mathematical’ structure was easier to construct for his debut. How Amenábar ‘imitates’ Hitchcock in Thesis lies above all in his working methods, in an almost overbearing attention to planning and detail in order to replicate American, or especially, Hitchcockian genre standards.4 For example, as the veteran cameraman Hans Burman who shot Thesis comments in the ‘Making Of’, there are a very high number of shots per sequence for a Spanish film of its time. Psycho’s shower scene is not only the most obvious reference for the thriller genre, but moreover the gold standard of an incredibly high number of shots per sequence. In the scene in which Bosco (Eduardo Noriega) chases Angela (Ana Torrent) throughout the Facultad, or school of the college, Amenábar aspires to surpass this standard. He not only storyboarded the sequence, following Hitchcock’s meticulous working methods, but also composed the sequence with a high number of shots, including inserted close-ups. Because of the number of shots the sequence, which ended with Bosco catching Angela by surprise from behind, took two days to shoot.

After a long chase through the university corridors, Bosco (Eduardo Noriega) catches Angela (Ana Torrent) from behind and she turns to face her pursuer in Thesis.

Thesis broke new ground in Spanish terror films through its reliance on strings and piano in its soundtrack to the exclusion of brass instruments. Like Bernard Herrmann’s soundtrack to Psycho, which famously employs discordant string instruments to evoke terror and suspense, Amenábar attempted a similar effect in his composition. Despite its embedded technology which tries to capture the attention of a youth audience, for instance the way the music that Angela (classical) and Chema (Fele Martínez) (heavy metal) listen to through ear plugs in the school’s cafeteria is used to characterise them, Thesis still evokes older films, and their mise-en-scène, as well. In the opening credit sequence the ticket collector comes on the train personally to announce a death on the tracks and to tell the passengers not to look at the body. He poses in the train car like the announcer at the theatre in The Thirty-Nine Steps or the one who appears to introduce Frankenstein in Spirit of a Beehive. A more likely contemporary scenario would have been for the announcement to come only over the loudspeaker system. The official is lit slightly from below as were those stage announcers. His clear enunciation and resonant voice recalls theirs. This direct address creates the retro atmosphere of a horror film.

Don’t look now!: The ticket collector (Walter Prieto) faces the passengers to tell them not to look at the dead body on the tracks as if they were an audience at a horror movie in Thesis.

Amenábar refers to Hitchcock directly when he comments on how he and Mateo Gil conceived of Thesis’s plot. For example, he says the snuff film was ‘a good pretext, almost a “McGuffin” to construct a thriller with’ (Heredero 1997: 105). Also he mentions that they struggled with how to present multiple assassins and still sustain the suspense of the film, since they had a Hitchcockian admonishment in mind that Hitch hated whodunits. Both Psycho and Thesis construct their mysteries and build suspense in the flight from psychopaths by relying on subjective point-of-view shots. These shots mimic the glances of the impatient young women – the sisters Marion (Janet Leigh) and Leila (Vera Miles) in Psycho, and Angela and, to a lesser extent, her sister Sena (Nieves Herranz) in Thesis.

Thesis evokes Psycho’s Norman Bates in the characterisation of both the young male protagonists Bosco and Chema. As strong characters they presented Amenábar and Gil with a dilemma in their attempt to avoid making the film a whodunit. Casting an attractive Anthony Perkins as the psychopath Norman Bates was considered one of the more daring elements of the film in its time. The sexy Noriega, who resembles a heavier Perkins, as Bosco challenges the viewer in Thesis to accept a young, attractive and well-mannered killer. Yet the characterisation of the outcast Chema also picks up on elements of the less than confident Norman Bates in the mise-en-scène of Chema’s creepy apartment and in the witty bantering of the Chema and Angela.

In its visual tricks and its dialogue Thesis evokes and adapts Psycho through its profound appreciation of Hitchcock’s humour. Amenábar comments that his original concept for Thesis moreover was to depict metacritically the aesthetic devices of cinematographic violence and humour:

In the beginning I was more focused on showing the mechanisms that movies are made with and the techniques that are used to communicate humour or violence. It’s an idea that I’ve put aside for the moment because I’d like to do a movie about how you make a movie within a movie. (Heredero 1997: 105)

Although Amenábar claims to have abandoned his grander metacritical project, Hitchcockian humour remains central to Thesis’s style and tone, and critical success.5 To give one example, Angela cautiously enters Chema’s apartment just as Marion entered Norman’s parlour. The settings make the viewers fear their owners. Norman has his taxidermy, with an impressive owl hung from the ceiling. In a similarly frightening decoration Chema has mannequins of bound bodies suspended in his dark corridor. In these sequences, the male protagonists explain and defend their unusual hobbies as they simultaneously implicate the female visitor in them. In Psycho Norman begins by complimenting Marion that she eats like a bird. He then takes a dominant role by making a joke of the saying and asserting his knowledge when he explains that birds actually eat a lot. Likewise Chema first invites Angela to have a bite to eat before he shows her the videos she has come to see, but she refuses, hence being an even lighter eater than Marion. Rebuffed, he stuffs his face from the refrigerator, and says ‘al grano’ (‘to the point’, or literally, ‘to the grain’) to her as they move to his bedroom where he matter of factly lists all the kinds of exploitation videos he has. The spectator is left to tease out the sexual innuendoes of the courtship dialogue reminiscent of Norman skirting around the topic of Marion being on the run. She, in turn, treads lightly around the topic of his insecurity. To deflect the tension, he affirms his manhood by saying of his taxidermy: ‘A man should have a hobby.’

House of horrors: The dark corridor of Chema’s apartment is decorated with bound mannequins suspended upside down from the ceiling in Thesis.

The humorous tone that is created by playing off the respectability of domestic situations is common to both films. Before the lovebird couple get ready to go their separate ways from the cheap hotel in an opening sequence of Psycho, Marion describes her dream of respectability in great detail. She wants them to have dinner at her house with the picture of her mother on the wall, even if they have to turn the picture around to make love later. Her control of domestic allusions in the dialogue gives her dominance in the scene, even though she is deeply disillusioned that her affair with this divorced man Sam Loomis (John Gavin) is not leading to marriage any time soon. She leaves the hotel room finally telling her lover he cannot follow her at that moment since he has not put his shoes on yet. This innocuous banter about a mother’s portrait in Psycho of course accrues greater significance, and pleasure for the viewer, in a second viewing, when we know Norman is matricidal.

Seething with resentment for having to endure a family dinner with the suspected killer Bosco, Angela turns her disdain on her clueless sister (Nieves Herranz) who is thrilled to receive Bosco’s compliments in Thesis.

In Thesis Angela’s mother (Rosa Avila) invites Bosco to join the family for dinner to Angela’s great dismay. Angela believes that Bosco broke into her apartment using the keys she dropped the day he chased her through the college. The dinner table conversation functions simultaneously in different registers for the viewer as did the Psycho dialogue. To the parents and to Angela’s sister, Bosco comes off as supremely well mannered and a good date for Angela, someone who makes harmless wedding videos, while Angela sees a dangerous adversary. She seethes with resentment of her family for putting her in the situation of having to have dinner with Bosco, who even has the gall to hit on her sister at the dinner table. Every time we see Bosco bite into his meat, for which he effusively compliments Angela’s mother, the spectator feels Angela’s frustration at not being able to reveal what she suspects about Bosco to her family. She is progressively confirming her suspicions that he makes snuff movies and may have killed his girlfriend Vanessa. The visual humour or irony is that the charming Bosco sinks deep into flesh and does not leave the female characters with an easy exit strategy.

The very title Thesis signals that Amenábar’s debut film has an imbedded didactic purpose, to demonstrate how cinema and its spectators are implicated in the transmission of violence. Thesis shows how the camera accosts Angela in her bedroom, just as in an earlier era Norman spied on Marion through a peephole in his office wall. In the nightmare sequences of Thesis the red ‘on’ light of the video camera blinks in the corner of the frame as Angela lies in bed. She later discovers the tapes of herself with these bedroom shots in Chema’s camera. In the film’s epilogue patients in the hospital crane to see the violent snuff images the television anchor warns them not to look at. Ironically, Chema and Angela portray the ‘good’ spectators as they walk away from the spectacle on television just as the screen goes black. The scene thus reaffirms a generational break – that the younger generation can walk away from the television violence that mesmerises their elders, even though they are its protagonists.

The perfect, carnivorous guest: as he bites into his meat, Bosco (Eduardo Noriega) leans in to compliment Angela’s mother on her cooking in Thesis.

The fundamental emphasis on a generalised movie experience was an important aspect of Thesis’s success in creating a new Spanish cinema in the 1990s. As Amenábar observes:

The movie’s theme is quite international. Its universe is fundamentally cinematic. There are no explicit references to Madrid or to any specific school, on the contrary the characters are universal and it’s not hard for people to identify with them. I suppose this is the reason it’s been one of the best selling Spanish movies in the whole world. (Vera et al. 2002a: 29)

Amenábar intentionally universalised Thesis, through location and characterisation, especially by choosing a genre film, in order to reach an international audience. These are tenets of Hitchcockian filmmaking, too.

As argued throughout this book, another one of the characteristics of Hitchcock’s filmmaking appreciated by Spaniards was his humour. While Psycho is seldom thought of as a funny film,6 its trailer, which ranks among the best known of Hitchcock’s trailers and likewise of his on screen introductions, is a hallmark of his droll humour.7 In it Hitchcock gives a walking tour of the Psycho set, pausing and making hand gestures that ostensibly acknowledge the viewer’s delicate sensibilities. He waves the camera away from the gothic mansion’s bathroom. This moment in the trailer tends to elicit laughter from the audience.

Despite this bathroom not being the site of the shower scene, the audience, connoisseurs of Psycho that we are, recognise this wink not as an affirmation of Victorian sensibilities but rather as a compliment to our status as knowledgeable viewers, if not voyeurs, who are part of the overall game. Hitchcock’s humorous, gemütlich tour plays with and diffuses the tension that he built up around the marketing of Psycho. This famous strategy would lock the audience in for the film’s duration.

In the trailer to Psycho, Hitchcock waves the camera away from visiting the mansion’s bathroom, ostensibly to protect the sensibilities of the audience.

The trailer for Thesis has none of the storyline of Hitchcock’s tour although it does share a certain Hitchcockian bravado in that Amenábar intended from the start to include the line ‘What is cinema?’ in the trailer.8 He saw this movie as a treatise on film itself. To understand his position, or thesis, the climactic wave scene deserves interpretation, as it furthermore underscores Almenábar’s debt to Hitchcock’s use of humour. Part of this scene is featured in the trailer, which opens with Ana saying to the camera, ‘Hello. I’m Ana and they’re going to kill me.’ Right before Bosco begins to film Ana who is tied to a chair (like a spectator in a movie theatre), to create his snuff movie of her death, he opens a door to a closet in the garage. From screen left in the frame out falls Yolanda’s body. Bosco picks up her hand and makes it wave, limply, saying ‘say hello to Ana’. It is a bizarre gesture that reveals to Ana and to the audience that Bosco killed his girlfriend Yolanda, as well as his friend, the missing Vanessa, and plans to kill again. The gesture’s ambiguity stands out. Throughout the film Bosco has played the suave, well-mannered, wealthy kid. The macabre and cheeky wave of Yolanda’s hand breaks the pattern and suggests that he is actually a psychopath.

In a macabre gesture Bosco lifts the hand of the dead Yolanda and waves it saying, “Say ‘hi’ to Ana.” in Thesis.

Bosco pushes the hand back into the closet. While I do not mean to suggest a direct allusion to Psycho’s trailer here, both films continually exploit and explore the concept of voyeurism, and in how they incorporate humour into this pursuit. Thesis relies on humour not just in the climactic scene but also throughout the film. Chema’s banter with Ana and other characters, like the security guard whom he bribes with pornographic tapes, is exemplary.

Thesis discloses how Amenábar mastered the art of Hitchcockian suspense punctuated with humour. This mastery paid off. The film made one of the most successful artistic and commercial debuts in the history of Spanish cinema, sweeping the Goya prizes in 1997, winning seven, including best film, best script and best new director.

IV. ABRE LOS OJOS: VERTIGO ‘CORRECTED’

Because of the success of Thesis, Amenábar’s second film Abre los Ojos (Open Your Eyes, 1997) was much anticipated. Given the accolades for Thesis, he now had the funding to fully realise his talent and aim for even bigger prizes in the global film market. Not the least part of the anticipation for Open Your Eyes was due to its announced reprise of both the thriller genre and the themes of audiovisual violence and voyeurism. Alongside the sexy Eduardo Noriega, Amenábar cast Penélope Cruz, a rising star internationally, coming off her role as the youngest sister in Fernando Trueba’s Academy Award-winning Belle Epoque (1992), which traced her first love and sexual initiation. The stakes were high. Amenábar and his co-scriptwriter Mateo Gil turned to Hitchcock – in this case, one might even say, with a vengeance.

Open Your Eyes tells the story of César (Noriega), a handsome womaniser with family money and a huge modern Madrid apartment. In his bedroom he has an alarm clock that wakes him with an insistent recording of the title line, ‘Open your eyes’. César falls in love with Sofía (Cruz), an aspiring actress, when his best friend Pelayo (Fele Martínez) brings her as his date to a lavish birthday party at his apartment. At the party’s conclusion he leaves with Sofía and spends the night at her apartment. They talk, he sketches her, but they do not have sex. When his current, now former, steady girlfriend Nuria (Najwa Nimri), who was shunned at the party, comes by to pick him up the next morning at Sofia’s, she drives the car into a wall in an angry attempted murder/suicide. César survives the crash but his face is horribly disfigured, so much so that he has to wear a mask. The film moves in and out of César’s subjective world, in flashbacks and dreams, as he tries to make sense of his life. It follows his attraction for the two women, but especially to Sofía, the love of his life, for whom Nuria doubles visually in his dreams.

César is particularly confused to find himself in a psychiatric penitentiary for a murder he doesn’t remember committing. There, under protest, he undergoes therapy with a psychiatrist and discusses possible reconstructive surgery with a team of doctors. Part of the puzzle he puts together from his subconscious dreamwork leads him to uncover a corporation called Life Extension, represented in television ads by the mellifluous Serge Duvenois (Gérard Barray), with a dubious scheme for cryogenic preservation of bodies. In the film’s final scene on a skyscraper rooftop, which brings together the film’s overarching themes of life and death, César confronts all the major characters from the film. Duvenois reveals that the characters are only figments of his imagination, for when César despaired at never having his face reconstructed, he committed suicide and was then frozen until 2045, which is supposedly the current moment. Duvenois tells César that he has been living a nightmare of his own creation, but that he can choose a different dream if he commits suicide again. After a brief hesitation on the precipice to observe that he suffers vertigo, César jumps from the building.

Though it is difficult to disentangle the plot of Open Your Eyes, which confused critics and viewers alike, no one missed the message that this was a supremely ambitious film.9 Simply put, in Open Your Eyes Amenábar remade Vertigo in a contemporary setting and corrected Hitchcock’s ‘errors’. In the press Amenábar was vocal about his intentions and his judgement of Hitchcock. He gave the most complete exposition of his argument to the critic Carlos Heredero for the latter’s interview book Espejo de miradas. Because it so directly concerns Amenábar’s relationship to Hitchcock, it is worthwhile reviewing the relevant exchange in its entirety. Heredero asks Amenábar, ‘Dreams, the obsession with the gaze, the reality or irreality of death … there are many elements, besides a quite explicit quotation, that refer to Vertigo. What motivated you to use this reference and how does this relate to your film?’ Amenábar answers:

Vertigo is the story of a man obsessed with transforming one woman into another one, and Open Your Eyes tells the story of the protagonist César’s obsession to separate the images of two women who he mixes up, to the extent that when he’s fucking one of them, she suddenly transforms into the other one. In this sense it could be said that my movie is a kind of Vertigo, but backwards, taking into account that mine can also be considered, basically, an explicitly romantic love story. (1997: 109)

Significantly Heredero pursues this line of questioning to ferret out Amenábar’s Hitchcockian intentions: ‘Do you realise then that you’ve tried to make a Hitchcockian movie in spite of the fact that you think Hitchcock is overrated?’ Amenábar replies not only with an extensive critique of Vertigo, but also with a generalised complaint about Hitchcock’s status as filmmaker:

Of course it’s a very Hitchcockian movie, but this doesn’t take away from the fact that I think the whole beginning of Vertigo, that attempt to communicate the progressive obsession that Scottie is feeling there, is handled very awkwardly. That movie had great possibilities, but I think it was a great error on his part to allow the viewer to find out the solution to the mystery in the middle of the film. I think it would’ve been much more effective if the audience wouldn’t have known until the end whether Judy was or wasn’t the same woman as Madeleine. I realise that I can be even more inept in my own films, but some of Hitchcock’s little tricks leave me cold and he doesn’t always seem all that skillful. (Ibid.)

As a follow-up Heredero moves to probe how Amenábar’s recognition of Vertigo’s defects – in Spanish Amenábar uses the word ‘torpe’, meaning awkward or clumsy, to describe them – influenced his concept for Open Your Eyes: ‘This very particular reading that you make of Vertigo can explain the fact that in Open Your Eyes you almost always try to control the identity of César’s gaze and what the viewers can see…’. Amenábar agrees, elaborating on his intention in the film:

What I intend is for the viewer to live exactly the same deception that César does, and for this reason the spectator’s position coincides with that of the protagonist for at least eighty percent of the film. With this in mind, in this case I’ve had to very carefully plan out the point of view from which to film each situation and where to place the camera. This way just as César has trouble understanding what is happening to him, so, too, the viewer has trouble understanding what’s going on. Even in the actual climax we see and hear what César sees and what they tell him. They don’t leave him any other choice but to believe or not believe it, and the viewer ends up in the same position as him then. This is what the game’s about. It’s precisely the reason why the end of the film is told, but not seen. (1997: 110)

Amenábar’s comments were so explosive that Oti Rodríguez Marchante in the introduction to Amenábar, voluntad de intriga (Amenábar: Will for Intrigue, 2002), the first interview book on Amenábar in Spain, almost feels the necessity to come to his defence and downplay them in order to reassert Amenábar’s precocious genius:

Besides showing his precocious and natural talent, his ability to create controversy appears put together with an explosive mix of sincerity, meditation, ingenuity and dynamite. Only with this temperament and a clear conscience would a young, strong-willed film director get the idea to question openly and publicly some classic movies and their untouchable directors. Amenábar has had to dedicate a good part of his public interactions with the press to nuance and contextualise some declarations he made about the movie Vertigo by Alfred Hitchcock. (2002: 15)

It goes without saying that allowing Judy to reveal the ruse in a letter at Vertigo’s midpoint, which lets the spectator appreciate her point of view and torment almost as profoundly as Scottie’s, does not have to be considered a falling off in quality on Hitchcock’s part. The American Film Institute ranks Vertigo number one as the best ‘mystery film’ ever; the 2012 Sight & Sound survey ranks it as the best film of all time. Yet what is clear, putting this bluster over Hitchcock’s reputation aside for a moment, is that Amenábar wanted to reconfigure Vertigo in two important ways; one, to delay the revelation to the audience, and two, to focus exclusively on the subjective reality of the male protagonist, to limit himself strictly to what he calls ‘first person narration’ (Rodriguez Marchante 2002: 67).

Amenábar calls his reconfiguration a ‘reversal’ of Vertigo. This can be understood in different ways. For one, in general terms where Scottie tried to make two women into one, Judy into Madeleine, César tries to separate Sofía from Nuria. For another, more specifically Open Your Eyes does reverse the order of the defining events of Hitchcock’s film. Vertigo’s plot is a spiral as is the film’s overall artistic concept, from Saul Bass’s credit sequence of a swirl superimposed on a red open eye, to Hitchcock’s famous stairwell vertigo shot. The end of the film circles back to the beginning as it positions Scottie between life and death on the bell tower as he was on the edge of the city roof. Open Your Eyes on the other hand places Nuria’s suicidal crash, which is analagous to Judy slipping off the bell tower, towards the beginning, but it ends with a rooftop scene, the opening and original setting for Scottie’s vertigo. This is the reverse order of Vertigo’s plot.

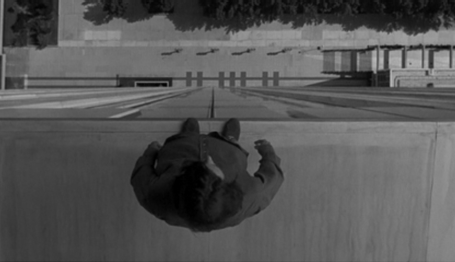

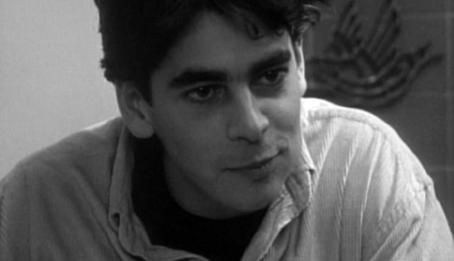

As a prelude to discussing the plot intricacies in even more depth, and probing the psychoanalytical interpretation of the film, it is instructive to acknowledge the existence of, and to explore the place the director’s cameo has in, Amenábar’s Vertigo remake. Open Your Eyes is the only Amenábar film in which he appears on screen. The presence of a director’s cameo has always been associated with Hitchcock and Amenábar adheres to the convention of this well-known feature. As Richard Allen writes regarding ‘The Author in the Film’ in Hitchcock’s Romantic Irony, Hitchcock’s cameos ‘playfully draw attention to Hitchcock, the director, as a presence behind the work, by inscribing that presence, not as a character in his films but as the flesh-and-blood director who populates his own film as an extra’ (2007: 21). In Vertigo Hitchcock appears crossing a street carrying a horn case. In Open Your Eyes Amenábar and his longtime buddy Mateo Gil cross paths with the protagonist César at a nightclub. They appear as nameless extras, as Hitchcock did in Vertigo. Amenábar and Gil taunt César as they are exiting the men’s room as César is urinating. When Gil tells César ‘Fix your face,’ Amenábar looks directly at César and laughs in his face.

In his cameo in Open Your Eyes, Amenábar laughs at César (Eduardo Noriega) and the line Amenábar’s co-scriptwriter Mateo Gil has just said (‘Fix your face’) as César exits the men’s room of a club.

This scenario cleverly acknowledges the role of Gil as assistant director and co-scriptwriter. In addition, as in Hitchcock’s cameos, which often took place at bus stops or on the sidewalk, Amenábar/Gil’s cameo occurs in a public place. Whether the twosome make fun of themselves, as Hitchcock does in Lifeboat where he stares longingly out of an ad for a diet aid, is less certain. Perhaps the men’s room set and male duo indirectly refer to Amenábar’s coming out as a gay man; however, he only made that revelation public in Shangay Express, a free Spanish newspaper for the gay community, in 2004, seven years after the release of Open Your Eyes.10

More significant to our reading of the film is the relationship of the authorial cameo in Open Your Eyes to the interpretation of the narrative, especially its structure and pace. As Richard Allen, citing Michael Walker, remarks: ‘Hitchcock’s cameos are often carefully timed interventions in the story which signal a decisive shift in the action as the protagonist “crosses a threshold” into the shadow world’ (2007: 22). Allen further explains:

These appearances achieve their most self-conscious form when Hitchcock actually seems to acknowledge his role in orchestrating or precipitating the narrative action. This is nicely illustrated in his cameo appearance in Rear Window, where the attentive viewer will observe Hitchcock repairing the clock in the apartment of a composer who is struggling to write the song that will become the love theme of the film. As John Falwell has argued, Hitchcock through this gesture identifies himself with the composer as the orchestrator of his film. (2007: 22–3)

The Janus shot in Open Your Eyes: César (Noriega) in profile facing one way with his mask on the back of his head facing the other.

To a certain degree Amenábar and Gil, through their mocking do ‘precipitate’ the narrative action and mark a shift into a ‘shadow world’ for César. The extensive nightclub sequence and the parting on the way home lead César to a crossroads in his life, the decision to actually take his own life. This is symbolised artistically through what I am calling the Janus shot, in which his profile faces one direction and the mask on the back of his head faces another. When César leaves the men’s room after being laughed at by Amenábar and Gil, his ego is too deflated to continue trying to resume his old life. He is surrounded by the club crowd rave dancing. He picks up his mask where he had discarded it and places it on the back of his head. The camera frames César’s profile in a shot that symbolises his dual consciousness as old and new selves.11 He makes himself so drunk he returns to the men’s room to throw up. The Janus shot is repeated a second time here as we watch him vomit. Afterwards César stares at himself in the mirror as if taking stock of his life. The Janus shot is repeated yet again as leitmotif when he joins Sofía, and later Pelayo, too, in conversation at the bar. Throughout the bar sequence César stands off to the right side of the frame with his face and mask in profile.

Sofía (Penélope Cruz) and César (Noriega) in a Janus shot talk at the nightclub’s bar.

‘Open your eyes’: Nuria (Najwa Nimri) in close-up as if seen from the angle of César lying on the pavement.

Pelayo, Sofia and César exit the club together and say their late-night good-byes in the street before going their separate ways. Sofía leaves first, and then Pelayo hurries off after her. A jealous César cannot bear the thought that after Pelayo rounds the corner out of sight he is actually reuniting and hooking up with Sofia. César runs after them and collapses. The film cuts to a black fade. A female voiceover says: ‘Open your eyes.’ This sequence, which begins with the black fade, is key to understanding how Amenábar revises Vertigo. In it the order of shots limits the perspective to that of César. First Nuria appears in blurred close-up as if from the angle of César lying on the pavement, then the film cuts to a reaction shot of César gasping at the vision of her, and finally the film quickly cuts again to a close-up of Sofia from the same low angle. The black fade accompanied by a female voiceover in Open Your Eyes functions as far more than a simple transition. Not only does it significantly disorient the viewer, but it also acknowledges the role of the moviegoer as an interpretative subject in this play of doubles. In psychoanalytical terms, the black fade sutures the viewer into Amenábar’s obsession for Vertigo. Specifically it revises the crucial revelation at Vertigo’s midpoint, which is another female voiceover, as Judy mentally composes her confessional letter to Scottie. Open Your Eyes delays the Vertigo revelation through how the female doubles are depicted. In Vertigo Scottie forces Judy to become Madeleine, and she acquiesces. Judy tears up the confessional letter and decides to become Scottie’s lover, the object of his obsession, no matter what the consequences. On the other hand, in Open Your Eyes César desires Sofia, but Nuria blocks this desired transformation and interposes herself in his dreams. This blockage appears in the pavement sequence, just discussed, and in a later sequence in Nuria/Sofia’s apartment, to be analysed shortly. First, however, it is important to take stock in more general terms as to how Open Your Eyes both reconfigures Vertigo while it uncannily repeats the latter’s artistic leitmotifs.

There are few films that can benefit from formalist interpretation of storytelling in terms of fabula (the complete chronological story) and syuzhet (the reorganised version of events that plays out on screen) as much as Open Your Eyes.12 The first half of the film almost lulls the viewer into thinking that the two develop simultaneously, and consequently the plot develops in a linear fashion. Only one early scene signals a possible disjunction, through the presence of the uncanny. César discovers a deserted Madrid, specifically an empty Gran Vía in the morning. The sequence hints at the existence of another reality, or at least the genre of a sci-fi film. Yet an educated viewer, the same kind of viewer Hitchcock took on Madeleine’s obsessive visits to the gallery of the Legion of Honor to see Carlotta’s portrait, might recall how the Spanish artist Antonio López García, considered a supreme figurative or realist painter, depicted precisely this avenue as devoid of people after stationing himself on the Gran Vía at dawn day after day over a period of years, in order to record this tableau. The desolation of the familiar is considered one of the characteristics of López’s work that received its first major exhibition in Madrid in 1993.13 However after the nightclub scene, where Amenábar appears to assert his directorial presence through the cameo, fabula and syuzhet diverge, and the sense of the film as a dream world is much stronger. In the movie’s final scene, called ‘Final Realization’ on the DVD, the representative of the Life Extension corporation, Serge Duvenois, tells César that a ‘empalme’, or splice, was made in César’s life the night of the nightclub visit. It was the night of Janus because he led two lives thereafter. Duvenois explains that after that night a reclusive César gave up on restoring his face, signed a contract with Life Extension to be frozen, and committed suicide by taking pills. Duvenois encourages César to commit suicide again to enter into a different dream.

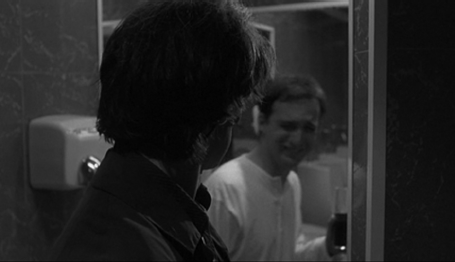

The film’s narrative from the dividing point of the nightclub sequence is a different nightmare. It is far more disorienting, more synchronous, than the first half of the film. Moreover, as Open Your Eyes transitions from what in classical formal analysis would be from exposition to complication, Hitchcock’s Vertigo assumes a more prominent role artistically as the model for César’s wish fulfillment that was signalled by the female voice intoning ‘Open your eyes’. At the same time as the correction of Vertigo, with the interference between the female doubles, becomes more prominent, so, too, does the emphasis on César’s subjectivity increase. As he lies in the street, César wakes up to the image of Sofía over him. They proceed to have sex in her apartment. The duality of the situation, as reality and dream, and the primacy of César’s subjectivity to the film’s interpretation, is signalled in another bathroom scene. This one is in an apartment rather than in a nightclub. César wakes up once during the night and heads to the bathroom. There he sees his disfigured face in the mirror. Frightened he goes back to bed with Sofía. He wakes up again to repeat his trek, but the second time he sees himself in the mirror restored to his former handsomeness.

In this second half of Open Your Eyes César’s dual consciousness becomes synonymous with his condition of romantic love. Two sequences, both of which convey romantic love, directly allude to Hitchcock’s Vertigo and employ his well-known cinematographic techniques. César goes to an apartment, which we identify as Sofía’s from the figurines of mime artists that appear in the foreground. All he encounters, however, are photos of Nuria where before he had seen ones of Sofía. As he ransacks the place in fury, Nuria hits him over the head with a bottle and he falls down. He wakes up to Nuria standing over him saying apologetically that she thought he was a robber. The close-up of Nuria’s face is hazy. At his request she goes to get him a glass of water. The film cuts from a close-up of César prone on the floor to a medium shot of Sofía in a haze coming through the door and framed by it. The sequence alludes to the transformation sequence in Vertigo in which Judy enters the hotel room where Scottie is waiting for her after her daylong makeover in the image of Madeleine. Judy as Madeleine, platinum blonde and wearing the grey suit Scottie picked out for her, enters the hotel room in a fog of light. She has realised his romantic dream. Amenábar’s adaptation of Vertigo here is straightforward. César’s desire, like Scottie’s, is to possess the innocent or aloof, romantic partner—not the slutty, sexually available Nuria/Judy. They realise their desires.

Open Your Eyes alludes to Vertigo: a medium shot of Sofía (Penelope Cruz) in a haze coming through the door and framed by it, as she appears to César.

Green haze in Vertigo: Judy (Kim Novak) coming out of the hotel bathroom to reveal to Scottie her transformation into Madeleine’s image.

Romantic rotating close-up shot of Sofía and César kissing in Open Your Eyes.

Scottie kisses the transformed Judy in Vertigo’s hotel room sequence.

As the sequence progresses, César embraces Sofia. Their kiss is filmed in a rotating shot that recalls the hotel kiss in Vertigo in which Scottie’s memory of taking Madeleine to the mission stable is a background projection. The soundtrack to this sequence, which culminates in César and Sofia naked, making love, is one of the most symphonic moments in the film’s score. Unlike Vertigo’s score for the hotel room transformation, which repeats the romantic musical theme of the film, and hence emphasises the image of Madeleine as the sublime Other, the music in Open Your Eyes conveys an ominous tone through the minor key punctuation of piano and violin phrases. It more resembles the eerie theme music that accompanies Vertigo’s credit sequence. The music reinforces the ever-present threat in Open Your Eyes that Sofía will again be revealed in César’s consciousness as Nuria. Whereas for most of Open Your Eyes the desire to separate Sofía and Nuria is prevalent, and in this the film differs markedly in emphasis from Vertigo, that strives to conflate the two women, this particular bedroom sequence points the way towards a common interpretation of the two films. Both Hitchcock and Amenábar are concerned with the role of loss in the symbolic order.

To explore Amenábar’s interpretation it is helpful to consider Slavoj Žižek’s analysis of the two losses that befall Scottie in Vertigo:

Hitchcock’s finesse consists in the way he succeeds in avoiding the simple alternative: either the romantic story of an ‘impossible’ love or the unmasking that reveals the banal intrigue behind the sublime façade. Such a disclosure of the secret beneath the mask would leave intact the power of fascination exerted by the mask itself. The subject would again embark on a search for another woman to fill out the empty place of Woman, a woman who, this time, will not deceive him. Hitchcock is here incomparably more radical: he undermines the sublime object’s power of fascination from within. Recall the way Judy, the girl resembling ‘Madeleine’, is presented when the hero runs into her for the first time. She is a common redhead with thick makeup who moves in a coarse, ungracious way – a real contrast to the fragile and refined Madeleine. The hero puts all his effort into transforming Judy into a new ‘Madeleine’, into producing a sublime object, when, all of a sudden, he becomes aware that ‘Madeleine’ herself was Judy, this common girl. The point of such a reversal is not that an earthly woman can never fully conform to the sublime ideal; on the contrary, it is the sublime object herself (‘Madeleine’) that loses her power of fascination. (1993: 85)

Žižek elaborates on this ‘second loss’ in which ‘the whole fantasy structure that gave consistency to his being falls apart’ (1993: 86):

Madeleine’s ‘second death’ functions as the ‘loss of loss’: by obtaining the object we lose the fascination dimension of loss as that which captivates our desire. True, Judy finally gives herself to Scottie, but this gift of her person ‘is changed inexplicably into a gift of shit’: she becomes a common woman, repulsive even. This produces the radical ambiguity of the film’s final shot in which Scottie looks down from the brink of the bell tower into the abyss that has just engulfed Judy. This ending is at the same time ‘happy’ (Scottie is cured, he can look down into the precipice) and ‘unhappy’ (he is finally broken, losing the support that gave consistency to his being). This same ambiguity characterizes the final moment of the psychoanalytical process when the fantasy is traversed; it explains why a ‘negative therapeutic reaction’ always lurks as a threat at the end of psychoanalysis. (Ibid.)

César’s disillusionment in the final scene, his learning that Sofia (further idealised by her white gauzy dress) and his psychoanalyst Antonio were figments of his imagination, is likewise a loss of a loss, as explicated by Žižek.

Though we have seen here how Open Your Eyes alludes to specific shots from Vertigo, of the fog and the kiss, and thus adapts Hitchcock’s artistic vision most directly or formally, it is important to consider how Open Your Eyes incorporates indirectly, in the logic of the film, the famous tracking shot from Hitchcock’s film. Again Žižek’s Looking Awry, especially the section entitled ‘The Hitchcockian Blot’, may serve as an important guide to our comparisons of the two films. Since the exposition of Žižek’s text is a rather dense detour, it may be helpful to preview our argument. Significantly, the black fade in which a female voice intones ‘Open your eyes’ is analogous to what is commonly called the vertigo shot. Both black fade and vertigo shot represent the gaze turned back upon the respective film’s spectator and announce the maternal superego.

Žižek analyses films in terms of three stages – oral, anal and phallic. In formal terms for Žižek, ‘if montage is the “anal” process par excellence, the Hitchcockian tracking shot represents the point at which the “anal” economy becomes “phallic”’ (1993: 95). He explains, ‘“phallic” is precisely the detail that “does not fit,” that “sticks out” from the idyllic surface scene and denatures it, renders it uncanny’ (1993: 90) and further, referring to Lacan:

This is the way Lacan defines the phallic signifier, as a ‘signifier without signified’ which, as such, renders possible the effects of the signified: the ‘phallic’ element of a picture is a meaningless stain that ‘denatures’ it, rendering all its constituents ‘suspicious,’ and thus opens up the abyss of the search for a meaning – nothing is what it seems to be, everything is to be interpreted, everything is supposed to possess some supplementary meaning. The ground of the established, familiar signification opens up; we find ourselves in the realm of total ambiguity, but this very lack propels us to produce ever new ‘hidden meanings’: it is a driving force of endless compulsion. The oscillation between lack and surplus meaning constitutes the proper dimension of subjectivity. In other words, it is by means of the ‘phallic’ spot that the observed picture is subjectivized; this paradoxical point undermines our position as ‘neutral,’ ‘objective’ observer, pinning us to the observed object itself. This is the point at which the observer is already included, inscribed in the observed scene – in a way, it is the point from which the picture looks back at us. (1993: 91)

Žižek details how several artistic innovations in Hitchcock’s films, among them the vertigo shot, function as the ‘phallic’ spot or ‘blot’. A black fade with a voiceover is nothing new. However, the disembodied voice saying ‘Open your eyes’ after we have witnessed César’s fall likewise acknowledges our voyeurism, the essence of cinema. We may have closed our eyes to avoid seeing death. Thus, we have been, in Žižek’s words, pinned to the observed object, and inscribed in the scene, afraid of our own death as well as of César’s. The voice of the maternal superego speaks and asserts her power over life and death.

Bird’s-eye-view of César on the edge of the roof in the climactic scene of Open Your Eyes.

In an overhead shot in Open Your Eyes César bends backward on the roof’s edge, body foreshortened, as in the optical illusion of Dalí’s ‘Crucifixion.’

Although the two black fades in Open Your Eyes, at the suture of the ‘empalme’, or splice, at the film’s midpoint, and at the film’s end, are structurally analogous to the disorienting the vertigo tracking/zoom shot shot, neither a black fade or a female voiceover are particularly innovative as cinematographic techniques, as was the vertigo tracking/zoom shot shot in its day. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that Amenábar does experiment artistically and challenge Hitchcock’s status as innovator and cinematographic artist in the end sequence to Open Your Eyes in a different way. As he declared to Heredero in the interview quoted above, Amenábar intentionally maintains the perspective of César, with a far greater consistency than Hitchcock does for Scottie in Vertigo. However, right before the film cuts to show César jumping, in the image of Scottie’s psychedelic nightmare, there is a bird’s-eye, or God’s-eye, shot of César. This shot breaks with the consistency of representing César’s perspective. He is then shown bending backwards, which gives us an unusual perspective. His whole body is foreshortened and he looks up. As in the uncanny Gran Vía sequence, the reference here is to other well-known Spanish paintings, in this case of Salvador Dalí. Dalí experimented with perspective to represent both the Crucifixion and the Ascension, in a manner that merged Christian iconography with his personal mystical mythology based on ‘the metaphysical spirituality of the substantiality of quantum physics’ (quoted in Ades 2000: 164). The paintings ‘Crucifixion (Hypercubicus)’ and ‘Ascension’ show the Cross floating in space with the observer left in a ‘dizzying’ sense of space. The two later Crucifixions, two stereoscopic panels, ‘Gala’s Christ’ (1978), depict Christ precisely from the angle that the back-bending César is shown in Open Your Eyes (see Ades 2000: 182–3).

A reference to Dalí at this point in the film, as a dual allusion to Hitchcock whose Spellbound included a dream sequence designed with Dalí, seems particularly appropriate, as Duvenois has just explained that Antonio the prison psychiatrist (Chete Lera) was only a ‘necessary’ character in César’s ‘first’ dream, and hence should not be believed. Hitchcock vocally dismissed psychoanalysis as a bogus practice, thus striking out at his ‘father’/benefactor the producer Selznick, who avidly believed in it. In Spellbound the character John Ballantyne (Gregory Peck), who has assumed a false identity as Dr. Anthony Edwardes, undergoes analysis to discover the buried guilt for his brother’s death in childhood. In his dreams César, too, has been uncovering his guilt, not for killing a woman as the prison psychiatrist suggests, but rather class guilt. Sofía caricatured him as a soulless tycoon. He imagines their sexual climax as dependent on him putting money into her body as if she were a life-size bank. Previously in the film we have seen her strike a frozen pose as she solicits money as a street mime. To interpret the suicide sequence as a crucifixion emphasises the moral tone of the film, something that Amenábar shares with other Latin directors who have creatively translated Hitchcock’s films. Amenábar in the director’s notes to the US DVD of Open Your Eyes further personalises the moral message when he observes: ‘I might even agree with my producer, José Luis Cuerda, who suggested that César was a kind of punishment for the spoiled rich youth in my film Thesis.’

To conclude and underscore how Amenábar revised Hitchcock in Open Your Eyes, we may revisit the differences between the two films as seen in their endings. Vertigo universalises themes in the religious setting of the dénouement in which the Mother Superior appears to frighten Judy and precipitate her fall; Open Your Eyes in evoking Crucifixion iconography also makes a similar gesture. However, Open Your Eyes at the same time presents a more secular, relativistic option. It contextualises the climax as corporate scandal. César’s belief or lack of belief in Life Extension, and consequently his willingness to jump off the roof, is bracketed by the suggestion, uttered by the psychiatrist Antonio in that final scene, that César’s business partners plotted his demise to take over the catering firm and forced him into signing the Life Extension contract and committing suicide to carry it out. Vertigo had its Gavin Elster as evil manipulator of Judy’s fate, but his business was the prosaic shipping, never a whole corporation based on bogus science like Life Extension. Neither ending, of Vertigo or Open Your Eyes, however, can be interpreted as definitive closure. Vertigo had two different endings, for example, though the casual moviegoer would not have been aware of the duality since only one was ever shown at any given screening. Nonetheless, because it implies a rereading of all of the ‘events’ of the film as dreamwork, the ending of Open Your Eyes throws the spectator into a postmodern questioning of the integrity of subject, which is far removed from the classical Hollywood dictum that by the finale all plot elements be clearly resolved. This questioning is how Amenábar aggressively ‘corrected’ Hitchcock.

With its ending at the Spanish mission, and castanets giving the beat on the soundtrack to Scottie’s psychedelic nightmare, Vertigo stands out in its mise-en-scène as one of Hitchcock’s most atmospherically Spanish films. Even so Spanish audiences gave Vertigo only a bemused polite reception when the film was shown in competition at the San Sebastián Film Festival. They far preferred Hitchcock’s witty interviews to the actual film (see Bolín 1958). It took decades for the film to find the place in world film history that it has attained today.

It is unlikely that these more folkloric Spanish touches are what drew Amenábar to this classic in the first place. Nonetheless, Open Your Eyes, with in its setting in contemporary Madrid, is a uniquely Spanish interpretation of Vertigo, rooted in Spain’s cultural history, of urban architecture, home design and modern painting. Even more so than the original Vertigo, Open Your Eyes did not fare terribly well at gathering invitations to the official competition sections of the major film festival circuit. Still, it did win the Panorama award in Berlin, a lesser award than the Golden Bear, and best film prizes in Tokyo and Guadalajara. In Spain it was nominated for ten Goyas, but won none. Simply put, it was too dense. Yet even without the accolades, given that Open Your Eyes was a French/Italian/Spanish co-production with a budget of ‘300 milliones de pesetas’14 the film achieved considerable international distribution in theatrical and DVD release over a period of years. Finally, it is worth noting the timing of the film’s release was a particularly good career move since it was poised to feed off an increased interest in Hitchcock at the time.15 Open Your Eyes was launched on its international run in 1998, the year preceding the Hitchcock centenary. Already film magazines were gearing up in with special essays, such as Carlos Losilla’s ‘Hitchcock a la sombra del cine negro’ (‘Hitchcock in the shadow of film noir’) in Dirigido’s June 1998 issue. In the US in 1998 Gus Van Sant directed and produced the remake of Hitchcock’s Psycho for Universal Studios, which was met with a considerable backlash.16 During this decade Universal also oversaw the lucrative franchise of Psycho sequels – Psycho II (1983), Psycho III (1986) and Psycho IV: The Beginning (1990), all of which had different directors. Amenábar was not in the running to direct either a remake or a sequel, but his own film was ready for a Hollywood remake.

V. A REMAKE VIA THE STAR SYSTEM: TOM CRUISE’S VANILLA SKY, BETWEEN SCI-FI AND TRUE ROMANCE

Amenábar’s film caught the eye of someone with deep pockets and Hollywood insider knowledge – namely Tom Cruise. Cruise bought the rights to remake Open Your Eyes with the money he had made through his roles in Mission Impossible (1996) and Mission Impossible II (2000). As Stephen Holden wrote in ‘Plastic Surgery Takes a Sci-Fi Twist’ in the New York Times:

‘Vanilla Sky’ has been faithfully adapted from the Spanish filmmaker Alejandro Amenábar’s 1997 romantic thriller ‘Abre los Ojos’ (‘Open Your Eyes’) into a star vehicle for Mr. Cruise, its story transplanted to New York City from Spain and amplified by a blockbuster budget. Redemption (by true love or a heroic exercise of will) has been the theme of some of Mr. Cruise’s biggest hits, and here it takes on a more personal resonance than in any of his previous films. (14 December 2001)

Launching into the Hollywood saga of Vanilla Sky (2001), a star vehicle if ever there was one, was Amenábar’s crossover moment. Though Amenábar told Carlos Heredero he did not believe in the Spanish star system as a means of making a box office hit, he certainly had a different opinion of the potential of the Hollywood star system to further his career and to break into bigger budget markets.17 Amenábar and Gil received joint script credit for Vanilla Sky with its director Cameron Crowe. Cruise entrusted the project to Crowe as the latter had previously written and directed Jerry Maguire (1996), a huge hit in which Cruise starred.

It is entertaining to speculate what attracted the scientologist Cruise to Open Your Eyes – the sci-fi or the love story? His jet-set love affair with Penélope Cruz during the filming of Vanilla Sky, as a possible rebound from the end of his marriage to Nicole Kidman, was tabloid fodder and will always be associated with the film.18 As we saw above in Holden’s comments, most critics considered Vanilla Sky a faithful scene-by-scene adaptation of Open Your Eyes. To give just one example of the transposition, Cruise as David Ames wanders an empty Times Square, for instance, whereas César looked askance at the empty Gran Vía. The director Crowe in his DVD commentary expresses special pride at this Times Square sequence because they managed to empty out the heart of New York and do the scene without the assistance of CGI, as Amenábar likewise had when he imitated the uncannily realistic atmosphere of López García’s paintings. When we think of sci-fi and romance, it is worth a pause to contemplate that Amenábar may have perceived a melding of genres already in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, particularly when Madeleine wanders into the redwood forest and traces her life backwards and forwards, which others had not noted.19 However, the uncanny moment for which Vanilla Sky will perhaps be most eerily remembered today is for transposing the final leap from a skyscraper in Madrid to one in New York City. In Vanilla Sky the World Trade Center towers from which so many leapt to their deaths in 2001 are clearly visible.

Faithful adaptation of the Gran Vía: David Ames (Tom Cruise) wanders an empty Times Square in Vanilla Sky.

Despite the ominous premonition of its ending, the overall tone of Vanilla Sky is infinitely lighter than that of Almenábar’s original. For instance, when Sofia Serrano (Penélope Cruz) calls Juliana Gianni (Cameron Diaz) the ‘saddest girl to ever hold a Martini’, somehow the drink and Diaz’s coquettish image displaces the sadness. Shot from the back in her tight satin slacks as she holds her glass over her head, Diaz is a cute and sexy jilted lover, not the noir femme fatale that Najwa Nimri was in her red cheongsam in Open Your Eyes. The party is just livelier, more fun in Vanilla Sky.

This change in tone is in some ways ironic, since humour was one of the main selling points of Amenábar’s Thesis for a college-age audience. To recall, Vertigo confined, or even segregated, its humour to the sessions between Scottie and Midge, generally in her apartment and with cocktails. Who can forget Scottie staring at the cantilevered brassiere on a pedestal and Midge asking Scottie rhetorically if his mother didn’t teach him about women? Since Amenábar intentionally concentrated on César’s subjectivity and restricted the woman’s presence in Open Your Eyes, he eliminated the option of a Midge character, and with it most of the opportunities for humorous banter. Pelayo and César pick up the slack a little in their buddy humour about scoring with women, but these exchanges fall flat in comparison with Vertigo’s zingers. One notable exception of a joke that does work occurs in an interior apartment scene. When César asks Sofía what she does for a living, she replies she is an ‘arms dealer’. It’s so implausible, it’s funny. In Vanilla Sky Sofia uses the exact same line that she is an ‘arms dealer’, but it comes off even better because it fits the overall lighter, happier tone. The effect is moreover amplified as the early party scenes with the charming duo of Cruise and Cruz run twice as long as those in Open Your Eyes.

There are many ways in which Open Your Eyes was a particularly good candidate for a remake, and making it into a comedy was not one of them. Open Your Eyes was a relatively inaccessible art house film. Viewers got lost – though many enjoyed the confusion – in its postmodern markings in the indecipherable suspension of meaning. Hollywood smoothed out or clarified the plot. Motivation was made clearer, and more conventional cinematic techniques were used to signal to the viewer when a sequence is a hallucination.

What is much clearer in Vanilla Sky is the conspiracy of the Board of Directors against David to declare him incompetent due to the accident with Juliana. In Open Your Eyes César’s ‘socios’ or business partners are only mentioned in passing, never seen. Vanilla Sky adds a boardroom scene. Every one of the ‘Seven Dwarfs’, as the trust fund company managers are called, has an on camera introduction by Disney dwarf name. Likewise the Life Extension scheme is given an extensive on-screen sales pitch by the actress Tilda Swinton, playing Rebecca Dearborn, who explains the special option of a ‘Lucid Dream’ upgrade to the contract. In general Vanilla Sky makes the corporate structure visible with these humorous villains, whereas Open Your Eyes outlined the workings of capitalism more vaguely, as distant tentacles in César’s subjective world. Because they are presented overtly as seedy elements within a corporate structure, as opposed to David’s faithful, though still corporate, lawyer who wrests the company back for him, Vanilla Sky’s critique of capitalism is more easily dismissed.

The clarity of Vanilla Sky, whose title, as David explains, describes the sky in a Monet painting that he inherited, is not necessarily a virtue. There were jokes in the press about the film being plain vanilla compared to Amenábar’s film.20 With rare exceptions, Hitchcock remaking his own The Man Who Knew Too Much among them, remakes have horrible reputations in film history. Gus Van Sant’s Psycho is a key example of a lesser version of a classic. Lucy Mazdon in Encore Hollywood: Remaking French Cinema (2000) notes that the 1980s and 1990s marked a heyday for remakes of French films. Most well-known remakes of the time were comedies, such as Three Men and a Baby (1987) of Trois hommes et un couffin (1985) and The Birdcage (1996) of La cage aux folles (1978), though the thriller Nikita (1990) was also remade as The Assassin (1993) to considerable attention. Mazdon argues: ‘The act of remaking the films and the various ways in which they are received should be seen as related components of a wider process of cross-cultural interaction and exchange’ (2000: 2). Mazdon is particularly keen on debunking a general distain of ‘a much wider body of (particularly French) criticism which condemns remakes, dismissing them as “pap” purely because they are remakes and, by extension, ignoring the “vacuity” of the French films upon which they are based, terming them “fine Continental fare” simply because they are the source of a remake’ (2000: 1). In short, the European intelligentsia has long looked down on Hollywood. Ironically the huge poster of Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962) in David Ames’ apartment, which Roger Ebert in his review finds puzzling and out of place, partially answers the Europeans and reclaims the territory. The cultural markers of the apartment, of wealth, are French, i.e. the Monet painting and the Jules et Jim poster. On the one hand, this French décor simply characterises David as wealthy. To love Monet or French Impressionism is not particularly esoteric. Packing the art museums for Impressionist blockbusters is a common American cultural experience and represents mainstream tastes. However, a clip from Jules et Jim that is shown in the concluding sequence of Vanilla Sky suggests that David learned how to love from the film. To recall, Truffaut was the champion of Hitchcock and stood for a re-appreciation of commercial cinema, need we say, Hollywood cinema like Vanilla Sky. The film’s concluding sequence shows how movies, mostly American fare, gave shape to David’s reality. It is a sweeping vindication of the role movies play in the cultural consciousness in general in contrast to the singular reassessment of the solitary spectator of Vertigo that is Open Your Eyes.

To return to Mazdon’s call to interpret remakes in a wider context, the cinematic and cultural context from which Vanilla Sky and Open Your Eyes emerged began to position Spanish cinema broadly as European cinema. By 1998 Almodóvar had become a well-known Spanish director, but he was seen as a singular example. Moreover, because of his progressive sexual mores, Almodóvar was long seen as more French than Spanish. His films received far better press in France than in Spain, his work frequently premiered in Cannes. The remake of Amenábar’s film, or the cross-cultural exchange that it represented, had a more general significance for the emerging role of Spain in the European Union, and in twentieth-century global culture. Although André Bazin, among other critics cited in Mazdon, lamented that the remake had a ‘detrimental effect upon the films on which they were based’ because no one bothered to re-circulate the original (2000: 4), this ‘annihilation’, in Mazdon’s words, does not seem to have been the case with Open Your Eyes. It has continued in circulation, and in particular its availability in the US region code has depended more on the interest generated by Amenábar’s subsequent films, which reached yet further into global markets, or the repackaging of the DVD cover in the US to show Penélope Cruz’s cleavage as her career blossomed, than by any ‘quasi-Oedipal’ ‘act of violence’ by Vanilla Sky. In short, the cultural issues the French have with the US are of an entirely different order than those of Spain with the US. As seen briefly above, Crowe seems to acknowledge this, and perhaps even thumb his nose at the French, in the placement of Jules et Jim in the décor and in the sequence of clips from the movies.

In conclusion, Amenábar’s career benefited from the remake, however the two films are judged. Even if it did not rise to the box office figures of a Mission Impossible sequel, nor satisfy Cruise fans with more of the same, Vanilla Sky’s success was of a different order than that of Open Your Eyes. Like Open Your Eyes it garnered numerous award nominations, particularly for Cruise as Best Actor and Cameron Diaz as Best Supporting Actress, though few major prizes. The title song composed by Paul McCartney received the most recognition. However, Vanilla Sky actually marked a low point in Penélope Cruz’s crossover career for she was nominated for a Razzie as Worst Actress of the Year for her performance in it and Blow (2001).

Since he did not have artistic control over his film’s adaptation, the interpretation of Vanilla Sky, either as a version of Vertigo or of Open Your Eyes, which we have attempted here, is perhaps less significant than the mere fact of the huge recognition that a Hollywood remake of his work represented. Some would say Amenábar sold out to Hollywood commercialism and compare him unfavourably to Almodóvar who has famously resisted the chance to remake any of his films in Hollywood – by 1998 Almodóvar had already received many offers to remake Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, for instance. Nonetheless buying into the remake for Amenábar led to an entirely different category of stars becoming accessible to him in casting future projects. Cruise’s interest made Amenábar a known quantity at a relatively early stage in his career. The special feature ‘Hitting it Hard’, contained on the US DVD with clips from Cruise and Cruz adored by crowds on a world marketing tour, shows just how powerful the Hollywood marketing machine can be. The feature ends with the film’s opening night in Madrid and subsequent party. Cruise tries to sing in Spanish. Almodóvar dances. Amenábar appears hugging Crowe and smiling with a rather more satisfied look than the ‘Fix Your Face Dude’ gave César and us in Open Your Eyes.

VI. THE OTHERS: CROSSING TO HOLLYWOOD VIA REBECCA

In his brief preface to the Spanish edition of the script for Los otros (The Others, 2001), an immense glossy full-colour book, Amenábar looks back on his career trajectory and compares this project to a little boat crossing the Atlantic for an encounter with ‘the others’:

I wrote The Others in the summer of 1998 with a spirit very similar to that which took over me when I wrote Thesis. I just let myself get carried away with wanting to enjoy myself – that is, to frighten myself. I never thought that it would end up being my next movie, or that that little boat, that is a project when it is born, would cross nothing less than the Atlantic, and would put us in contact with ‘the others,’ the Americans, on a completely new journey, an unusual one I’d say, for Spanish cinema. The effort to get to port safely was intense and the apprenticeship was permanent. (Robles 2001: 7)

Using metaphors usually applied to Columbus’s encounter with indigenous peoples, Amenábar expresses not only personal pride for what he learned by making the film, but also more significantly pride for what the product represents for Spanish cinema – that is, the exceptional achievement of crossing over to Hollywood as no other Spanish director had done before. Although Vanilla Sky showed that Amenábar’s films were viable products for adaptation in a global market, The Others, whose script he wrote and directed, represented his true crossover moment. Not only did it gain the backing of a Hollywood studio, but it was his first, and until Agora in 2009 his only, English-language movie. Indeed the launching of the two English-language projects, Vanilla Sky and The Others, was intimately connected. The deal-making happened in quick succession. Sensing the international potential of The Others when they read the script, Amenábar’s Spanish producers contacted Canal+ (France) and Miramax (US), both of which expressed interest in co-production. Subsequently when Amenábar travelled to New York City to meet Tom Cruise a few months after Cruise bought the remake rights to Open Your Eyes, he met Nicole Kidman there, too. Listening to Amenábar talk about The Others project in that initial meeting, Kidman expressed an interest in taking the lead role. Cruise then became involved as executive producer of the film, a role he had already assumed for Vanilla Sky.

Adding interest to the story of the deal, the story of Cruise and Kidman also continued to draw the attention of the popular press at the same time. Just as the romantic story of Vanilla Sky fed the tabloids a plotline for the Cruise and Cruz romance, the story of The Others, of a woman abandoned by her husband, drew parallels with Kidman and Cruise’s rocky marriage at the time. Cruise and Kidman had starred together in Kubrick’s controversial and sexually steamy thriller Eyes Wide Shut (1999). They separated in 2000 and later divorced in 2001. Narrative and star discourse tend to intersect in the public domain.

To recall, The Others tells the story of Grace Stewart (Nicole Kidman), whose husband left for war but in the present moment of the movie, 1945, has not yet returned to their home, which she believes to be haunted, on the island of Jersey off the French coast. Three servants – a housekeeper/nanny, ground-skeeper and maid – arrive looking for employment, before her advert was even printed in the paper. They are ghosts from another era of the house. Grace, whose staff has just mysteriously left, hires them to care for the house and her two photosensitive children, Anne (Alakina Mann) and Nicolas (James Bentley). To protect her children from the light, she is strict about the rules of the house. She keeps the curtains shut and locks every door behind her before opening another one. Even with all her precautions, numerous strange sounds and apparitions in the house disturb her and the children and provoke investigation. At one moment she witnesses her daughter, dressed in her First Communion dress transform into an old woman. Grace’s husband returns, but leaves suddenly again without explanation. Afterwards servants rising from the graveyard, who resemble photos from a book of the dead that Grace has discovered, approach the house menacingly. Grace locks them out. However, she and the children find themselves on the margins of the meeting of the living and the dead at a séance in the house. A new family living in the house wants to uncover who is haunting it and why. The séance reveals that Grace had suffocated her children, and then killed herself. The new family flees the house and puts it up for sale.

To deal with these megawatt stars, Cruise and Kidman, Amenábar had to modify his directing style. This was only one aspect of the crossover transformation that Amenábar underwent as a result of Vanilla Sky and The Others. Kidman, for example, expected to hear when a take was good and actively shaped her on-screen image through frequent conferences with Amenábar. It is hard not to see the predominant choices of backlighting and grey tones for all aspects of the mise-en-scène – in Amenábar’s words, ‘so that the faces of the actors stood out’ (Robles 2001: 229) – as accommodations to Kidman’s star status and to expectations of classical Hollywood cinema. Amenábar laments, ‘I would have liked to make a movie that truly seemed filmed in the 1940s’ (Robles 2001: 240). But he came close.

Not only are there significant parallels between the career paths and dealings with stars and producers of Hitchcock and Amenábar, but also The Others is in many ways, especially in terms of narrative structure and cinematographic art, a remake of Rebecca, Hitchcock’s first film in Hollywood. In his own crossover moment between 1939 and 1940, which culminated in the release of Rebecca, Hitchcock had similarly been swept up into the maelstrom of star commentary based on off-screen real-life family tensions. To recall, Rebecca follows the nameless second wife of Maxim De Winter (Laurence Olivier) in the mansion Manderley as she tries to fit into the larger than life image of Rebecca, the deceased but much remembered (especially by the housekeeper Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson)) first Mrs. De Winter. Hitchcock managed to use the implicit family rivalry between Vivien Leigh (Laurence Olivier’s wife) and Joan Fontaine (playing Mrs. De Winter) to his advantage. Olivier, comparing Fontaine unfavourably to his more famous wife on set, made Fontaine cower. By not censoring Olivier, Hitchcock captured the perfect look for the insecure second Mrs. De Winter.