I. INTRODUCTION: CAREER PATTERNS

Before 2006, when Guillermo Del Toro released his international mega-hit El laberinto del fauno (Pan’s Labyrinth), the Mexican director, born in 1964, had made five feature-length films, all within the horror or fantasy genre, that alternated between small-budget Spanish-language films in Mexico and Spain – Cronos (1993) and El espinazo del diablo (The Devil’s Backbone, 2001) – and Hollywood productions – Mimic (1997), Blade II (2002) and Hellboy (2004). Conventionally this alternation makes Del Toro the epitome of a successful crossover director. Unlike other Latin crossover directors, such as Álex de la Iglesia, Del Toro has consistently been successful at the box office. This success can be credited to his study of Hitchcock and a single-minded focus on the horror genre. But it is little known that Del Toro has assiduously studied not just a few classic Hitchcock films, but every one he ever made. In 1990 while he was a film professor at the state university in Guadalajara, and before he directed his first feature film, Del Toro published a well-researched book on Hitchcock. The monograph Alfred Hitchcock (1990) comprehensively surveys all of Hitchcock’s films, television programmes and unfinished projects.1 Undertaking this academic study gave him not only intimate knowledge of cinematic techniques, but also gave him insight into Hitchcock’s career in its entirety, as an industrial model. This chapter will explore Del Toro’s writings, specific allusions to Hitchcock’s films in his work, and their shared career patterns. Throughout we will speculate on to what extent Del Toro has gone beyond the notion of crossover in the transnational scheme of contemporary cinema.

The paradigmatic importance of Hitchcock for Del Toro’s career can be sensed in the following passage from the section on Hitchcock’s Frenzy:

The product of the ‘new Hitchcock,’ as critics and publicists hastened to call Frenzy, has the privilege of being the most perfect work of the last stage of the director, and the energy he needed to carry it out is equivalent to that which a young person would need in his first work, but, while all this may be true, it is ridiculous to proclaim a ‘new Hitchcock.’ Let’s not be mistaken, the movie is driven by the dark vision of a sceptical and skilful old man; the 70 years of frustration of Hitchcock and the 50 he spent being a ‘good boy’ in the industry, vomit out a savage work, which could pass for the fresh work of a young, rebellious, and furious filmmaker, but neither fury nor rebellion are exclusive to youth. Frenzy is the darkest, most personal and admirable creation of an old and tired poet of brutality. (1990: 474)

Del Toro’s profound admiration and understanding of Hitchcock as ‘the poet of brutality’ is evident in this passage. As he contemplated the hard road to his directing debut, he looked to Hitchcock for energy and inspiration. He writes as if the old man were advising the young Turk to persevere.

Structured as a critical biography of Hitchcock, Del Toro’s introduction to Alfred Hitchcock functions as a virtual aesthetic manifesto. Moreover, when he compares British and American Hitchcock, Del Toro defines his own values and reveals his career aspirations. Del Toro strongly defends the British period: ‘The films shot by Hitchcock during his so-called British period have received much less distribution than they should have and tend to be seen negatively – even by their creator – when in reality they are as interesting, and at times even more so, than those of his North American work, since they treat ideas and situations with an intensity and purity infinitely superior to the works which succeeded them’ (1990: 26). Del Toro chooses Blackmail to illustrate his notions of intensity and purity arguing that it is ‘more complex and subversive’, and in particular, more misogynist, than other British works, such as The Lodger. He cites examples in Blackmail from the attempted rape/murder scene in the artist’s studio. Interestingly, since Del Toro was struggling towards making his own debut film at the time he was writing, he agrees that the complexity of Blackmail was ‘a little overdone’ finding that a common defect of ‘first works’ (1990: 27). Although Del Toro is a firm defender of British Hitchcock, he does appreciate Hitch’s motivation to work in Hollywood: ‘He yearned to learn all the details of the foreign industry in order to achieve his total independence later on’ (1990: 29). Again this reads like a pep talk for Del Toro’s own career path: try to get to Hollywood to learn, but make enough money to have creative control on your own projects, or as it worked out for Del Toro, film Mimic to be able to make The Devil’s Backbone. Del Toro makes a particularly impassioned defence of Hitchcock being able to create masterpieces with few resources, a situation Del Toro himself faced in Mexico: ‘There are those who commit the stupid error of trying to wipe out with a stroke of the pen the importance of this era of the director, alleging that Hitchcock’s narrative, that is, his pyrotechnics, were still not fully developed due to the lack of resources in that era and that for this reason his filmic expression appeared very limited’ (1990: 27–8). Again foregrounding the Blackmail painter’s sequence, as well as citing others in The Man Who Knew Too Much and Young and Innocent, he dismisses anyone who doesn’t see these films as he does as ‘hydrocephalic’ (1990: 28). Apart from the minor impact of these comments in a longstanding critical debate, it is hard not to read these passages as Del Toro’s cry for recognition of his own project, for his own early career and for an emerging new Mexican film industry.2

After his introduction to Hitchcock, Del Toro devotes a short chapter to each film, beginning with a story synopsis and ending with a note on the place of Hitch’s cameo in the respective film. Because Del Toro pays detailed, careful attention to selected cinematic techniques of each of the films discussed, the book serves as undeniable evidence of Hitchcock’s influence on the filmmaker in his own work, all of which postdates the book. Overall, the book stands out both as a scholarly document, and surely, as an idiosyncratic view on Del Toro’s reactions to Hitchcock’s films, to which we will continue to refer in our discussions of the individual films. Offering one preview here will attune the reader to Del Toro’s voice in the book. While noting what the critics Leonard Leff and Donald Spoto, then the directors Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol, have to say about Saboteur, Del Toro adds: ‘It is impossible for me to overlook mentioning here the profound irritation that Robert Cummings, the prognathous (sic) actor to whom Hitchcock would later give the role of Grace Kelly’s lover in Dial M for Murder, causes me. In both films the “hero” gains in stature only because of the generic convention’ (1990: 227). Del Toro expresses what can only be called colloquially ‘pet peeves’ about many of the films through the discourse of an educated man, epitomised here by the Greek word choice ‘prognathous’, chiefly used in physical anthropology, meaning with a prominent or protruding lower jaw (OED). The preferences he developed watching Hitchcock, however, are deeply felt – a profound irritation or discomfort – and long held, indications of the tenacity that has enabled Del Toro to survive both in a studio system and in the world of independent film. To avoid what Del Toro saw as Hitchcock’s errors in settling for Cummings, a ‘B list’ choice according to McGilligan and whom Hitch himself called merely a ‘competent performer’ (2003: 301), Del Toro resolved early not to compromise on casting. In interviews on his film Hellboy, Del Toro prides himself on casting Ron Perlman as the hero. Perlman had supporting roles as the nephew of the evil businessman in Del Toro’s debut film Cronos, and as the leader of the Bloodpack in Blade II. When Kellvin Chavez asks Del Toro if he had any problems casting Perlman, Del Toro replies:

Yeah, we went through the usual song and dance. I just didn’t want to give in, I think the best thing in a movie is when you’re sharing the weight of the movie with someone that you trust completely and that you feel is capable of delivering the part perfectly. I think that for Hellboy, Ron Perlman was the only actor to do it really. And the studio was suggesting other, bigger names. That’s why it took me 5½ years to get it made, because I was very stubborn and I just stuck by my chosen actor. (http://latinoreview.com/films_2004/sonypictures/hellboy/guillermo.html)

Del Toro’s study of Hitchcock’s negotiations with the studios that led sometimes to lamented casting choices prepared him for his own prolonged battle over Perlman. Del Toro saw in Perlman the perfect actor for horror/fantasy films, which had fascinated him since childhood.

Like Almodóvar, Del Toro began filmmaking through trial and error with a Super-8 camera. Significantly, whereas Almodóvar was already a self-supporting worker in Madrid, precocious Del Toro was only eight years old when he began experimenting with his father’s camera, making movies with ketchup and his Planet of the Apes action figures. He refers to them as horror movies and that one ‘was filled with exploitation elements’ (Daniel Epstein Interview, 2003). At eight, he dressed up as a vampire sucking his sister’s blood for a family photo. The impact of his early films, such as Matilda, starring his mother as an invalid devoured by a giant foetus, resurfaces both in Mimic’s giant insects and in his obsession with demonic foetuses in jars in The Devil’s Backbone and Blade II.3 Del Toro credits his parents’ large, eclectic collection of art books, which included volumes on European masters as well as on comic book artists, with inspiring his visual abilities. Later in his teenage ‘film geek’ years (Epstein, ibid.), Del Toro spent seven years as the projectionist for a cinema club that each week showed two or three movies, including world cinema, in 16 or 35mm. This was before the advent of video in Mexico. Del Toro clearly has a broad-based knowledge of global film culture.

Unlike Almodóvar or Hitchcock, however, Del Toro was not just self-taught, but had formal university training in fields related to film. Del Toro attended his home town University of Guadalajara where he studied visual arts and opted especially to concentrate on short films and theatrical make-up. In 1984 he worked as producer on Jaime Humberto Hermosilla’s Doña Herlinda y su hijo (Doña Herlinda and Her Son, 1985) in which his mother Guadalupe Gómez de del Toro starred as Doña Herlinda. In 1985 he wrote and directed his first professional short film Doña Lupe. From there he moved to work in television. In 1986 he made his major directing debut with episodes of Hora marcada (1986–1990), a Mexican equivalent of The Twilight Zone. His friend Alfonso Cuarón, who would later make Y tu mamá también (2001) and Gravity (2013), also debuted on this series.4 Del Toro calls the Hora marcada experience ‘like a film school’ (Director’s Interview, Cronos DVD). Also in 1986 he began to storyboard what would become Cronos, his first feature-length film, which took eight years to make. Though coming at a different stage, before rather than after his feature film breakthrough, Del Toro’s career followed Hitchcock’s in working for a sustained period of time on a commercial television series.

Significantly Del Toro’s career both parallels and intersects with the development of film studies as an academic discipline. While he was imagining Cronos, Del Toro taught film at the University of Guadalajara between 1986 and 1992 and wrote Alfred Hitchock. According to Clara Cisneros Michel, a professor of literature at Guadalajara, who was involved in new programme development, Del Toro’s years at the University of Guadalajara coincided with the creation of a film degree there, a first in Mexico. The programme encompassed film production and cinema studies. This is particularly important because the recognition of film not only as an academic discipline, but also as a career track, happened not in the huge main state university, UNAM, in Mexico City, but at the campus of Mexico’s second largest city, Guadalajara. The presence of multinational tech companies, such as Hewlett Packard, in Guadalajara at the time added to the sense of the possible. Guadalajara had a ready market for those students with audio-visual skills.

Even though Del Toro’s main interest from his student days was special effects, as expected for someone with his longstanding interest in horror, this is one area where formal training was not available in Mexico. Looking elsewhere, he took Dick Smith’s US correspondence course to receive his Certificate of Special Make-up Effects Artistry. Today Smith, who did the make-up for The Exorcist (1973), posts Del Toro’s testimonial on his website: ‘Your course has been the catalyst for everything I dreamed to do.’5 In 1985 Del Toro founded Necropia, his own special effects company in Mexico. In an article in Dirigido, Quim Casas emphasised Del Toro’s pioneering spirit with this move:

Del Toro simply reasoned: at the moment of beginning the pre-production of Cronos there wasn’t in all of Mexico any company that could develop the types of effects, trick photography, and special make-up that he required. Hence, he decided to form his own team of technicians and invent everything he needed for his first feature film as he went along, just like the pioneers of cinematography and the creators of the most modest B-movies. (2004: 48)

Over the long gestation period of Cronos, Del Toro did special effects make-up on major films of top Mexican directors, such as Arturo Ripstein’s Mentiras piadosas (Love Lies, 1987), Luis Estrada’s Bandidos (Bandits, 1991), Nicolás Echevarría’s Cabeza de vaca (1991) and Paul Leduc’s Dollar Mambo (1993). Through these productions he made significant contacts in the industry, especially with Guillermo Navarro, who later served as his director of photography on Cronos, The Devil’s Backbone and Hellboy. These early projects depended on family ties, for Guillermo Navarro’s sister, Bertha Navarro, served as producer for Cronos.6

Whereas Hitchcock’s entry into the film industry was via set design, Del Toro’s was special effects make-up. Both specialised areas, which emphasise the role of the visual component in film, are unusual career paths into directing. Moreover, the high level of technical knowledge, which both Hitchcock and Del Toro acquired from an early stage in their careers, allowed them to invent new distinctive looks for their subsequent films. Both pursued these careers quite relentlessly, too. Undoubtedly Del Toro’s talents and know-how in special effects and make-up in the world of fantasy have enabled him to move in and between multiple industries, where others have failed. This background makes his work extraordinary, especially in Latin American cinema, since it has been a commonplace that peripheral industries cannot do horror well because the genre requires special effects, which in turn means high production values beyond their usual budgets. In sum, all of Del Toro’s films, which we will now consider individually, touch on the horror or fantasy genre.

II. HUMOUR, VISUAL PYROTECHNICS, AND MORALITY: FROM YOUNG AND INNOCENT, THE TROUBLE WITH HARRY, THE BIRDS, SABOTEUR AND PSYCHO TO CRONOS

Over eight years Del Toro poured everything he had learned into his first feature film Cronos. The result was a thoughtful, not particularly gory, vampire tale with visually rich and complex sets. When it was made, its $2 million budget ranked it as the second-most expensive Mexican film ever made, after Como agua para chocolate (Like Water for Chocolate, 1992). Although Like Water for Chocolate broke new ground internationally, Mexican cinema had a long track record with period costume dramas. Audiences connected easily with their melodramatic strains reminiscent of Mexican telenovelas or soap operas. Yet Cronos represented different generic conventions and technical aspirations altogether. It was quite a surprise that Cronos became a huge critical success, winning the 1993 Critic’s Prize in Cannes and nine Ariel awards, the Mexican equivalent of the Academy Awards, including those for best picture and best director. Just like Hitchcock, who was known, and often derided throughout his career, for his commercial aspirations, Del Toro aimed to make a commercial film viable in a global market beyond Mexico. To increase the film’s viability, he targeted different markets with specific language versions: one, an unsubtitled, bilingual version of Spanish with some English, primarily in the dialogue of the American actor Ron Perlman, for most markets; two, a version of Spanish with English subtitles for the world art-house market; and three, a dubbed, Spanish-only version for the US Latino market. Del Toro was so committed to this experiment he did some of the dubbing voices himself.7

Cronos begins with a voiceover narration telling how in 1535 an alchemist makes the Cronos device, a special golden timepiece in the form of an egg-shaped mechanical insect for a Mexican viceroy. Four hundred years later the same alchemist, who has survived as a vampire, is found dead in the wreck of a bank building. A beam from the building’s collapse has stabbed him through the heart. Fastforwarding to modern-day Mexico, Jesus Gris (Federico Luppi), an Argentine antiques dealer, discovers the magic device in an angel statue he buys. Playing with it like a toy in front of his granddaughter Aurora (Tamara Shanath), he sets the ancient mechanism in motion. When it pierces him, he turns into a vampire. In the meantime Dieter de la Guardia (Claudio Brook), a dying industrialist, relentlessly quests for this same Cronos device, which he knows to be a source of eternal life. De la Guardia lives over his factory in an apartment full of religious relics, books on alchemy and preserved organs. He orders his goon-like nephew Angel (Ron Perlman) to wrest the time machine away from Gris. Like De la Guardia, Gris himself begins to understand the powers of the device. Rejuvenated by periodic fixes or piercings, he now begins to crave human blood and follows a man with a nosebleed at a New Year’s party into the men’s room. There the nephew Angel kidnaps Gris. He later pushes him over a cliff in a car. After a funeral Gris rises from the dead. Only the granddaughter Aurora understands what has happened and hides him in her toy chest. She accompanies Gris to a showdown with De la Guardia at his factory. She kills the old man. Angel and Gris struggle and fall to their deaths. Instead of seeking rebirth this time, Gris destroys the device by smashing it with a rock. His wife and Aurora mourn his subsequent death, but human order, embodied and portrayed by this nuclear family, has been restored.

Cronos alludes to such a wide range of international cinematic classics, beginning with the threatening machinery of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, which morphs into the machinery inside the Cronos device, that it is hard to isolate only Hitchcock’s presence in the film. In fact, Victor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive is more of a consistent backdrop than any other one film. Cronos’s opening repeats the Rembrandt colouration and lighting of The Spirit of the Beehive. In both films a little girl befriends a ‘monster’. In the latter he is an escaped soldier to whom she unwittingly gives her father’s musical watch. Her father is a beekeeper. The Cronos device combines these motifs of watch and insect hive. However, both Erice and Del Toro appear to have looked back to Hitchcock for inspiration in terms of the role of nature. Interestingly, Del Toro refers to Erice several times in his book on Hitchcock, most consistently when he discusses the meaning of The Birds. He writes: ‘For Victor Erice, the presence of “a series of obsessions deriving from the notable Catholic education” of Hitchcock becomes evident in the film, and suggests the intervention of chaos can have a divine origin’ (1990: 431–2). Erice reads Hitchcock’s The Birds in terms of a markedly Catholic allegory. This allegorical approach manifests itself in the many layers to the structure of The Spirit of the Beehive, which Cronos repeats. The Spirit of the Beehive’s indirect metaphorical language, linking Franco and Frankenstein, allowed it to critique patriarchal society and avoid censorship. In Cronos capitalism, as symbolised by the industrialist de la Guardia, receives the brunt of the critique.

As Erice engages the imagination of the child Ana (Ana Torrent) in The Spirit of the Beehive, a child obsessed by seeing the film Frankenstein, Del Toro enters completely into a child’s fantasy in Cronos through the relationship between grandfather and grandchild. The desire to do so appears autobiographical. In the director’s commentary to the tenth anniversary DVD edition of Cronos, Del Toro says that his film is an homage to his childhood relationship with his own grandmother Josefina Canbreros who died a year before the film was finished.8 Her portrait appears on the bedroom wall in the final death scene of the movie.

Hitchcock did significantly incorporate children in dangerous situations into some of his films. In both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much, a child is kidnapped. The schoolhouse and the children’s party scenes are key locations for terror in The Birds. In Sabotage the young boy Stevie unwittingly carries a bomb in a film canister that explodes and kills him. Yet Hitchcock’s films rarely acknowledge the child’s point of view to the extent that Cronos, or even more so The Spirit of the Beehive, do. In a notable exception, the child’s point of view allowed for the frame structure of Hitchcock’s The Trouble with Harry. In this film the child Archie, while roaming the fields with his toy gun, discovers the dead body in question at the beginning and end of the film. In contrast Del Toro’s Cronos genuinely accedes to the pleasures of child play at key junctures. Yet when casting children, Del Toro’s point of view in Cronos, as was Hitchcock’s in most of his films, remains that of a sympathetic adult, rather than that of the child herself, as in Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive. When Hitchcock cast his own daughter Pat as a young daughter of a senator in Strangers on a Train, for example, she entered into an adult world of cocktail parties and acted as an adult. She prepared and served the drinks while making witty small talk.

Hitchcock is most present throughout Cronos in the film’s use of leavening humour. Two deliciously funny sequences of the mortician working to the beat of ranchero music illustrate the film’s pacing with comedy. Tito the mortician, moreover, serves as a Del Toro alter-ego since he is an under-appreciated macho Mexican make-up artist, doing his best work on a body he finds out later will be cremated. The first sequence begins with an insert shot of a lacy pincushion, a feminine detail associated with women sewing. The camera gradually pulls back to show the grimy mortician sewing together the now vampiric Jesús Gris’s face and jaw, as a foppishly dressed man looks on. The visual joke is gender-based, like that of the salesmen of lady’s under garments the fugitive Richard Hannay meets on the train in The Thirty-Nine Steps. In The Thirty-Nine Steps we first see the girdle held up, then the camera pulls back to show the two bourgeois salesmen in suits who are responsible for this incongruous display. The film cuts to a view of another fellow traveller, a priest overwhelmed with righteous disapproval and forcing himself to keep reading his newspaper. In this mortician sequence, as in sequence of The Thirty-Nine Steps, we find ‘la risa por contraste’, or humour through contrast (1990: 345), which Del Toro also praises when he analyses The Trouble with Harry. Del Toro defines it as when ‘generally, the everyday, impassive gentleman of five o’clock tea comes face to face with an absurd and chaotic scene’ (ibid.).

To the sound of ranchero music in Cronos, Tito (Daniel Jiménez Cacho) the macho Mexican mortician does his best work sewing up Jesús Gris (Frederico Luppi), now a vampire, while a foppish man looks on.

An incongruous display is good for a laugh: A bourgeois salesman, who the fugitive Richard Hannay meets on the train, holds up a girdle in The Thirty-Nine Steps.

In the second sequence that illustrates Cronos’s Hitchcockian pacing, the mortuary worker tries to start the crematorium fire. The situation recalls the kitchen scene of Torn Curtain when Paul Newman and the spy Frau struggle to kill off the bad guy, finally holding his head long enough in the gas oven. Similarly, getting a gas crematorium fire going to incinerate the vampire’s body is no easy task. It just will not light. The mortician has to go down into the cellar to check the gas line. In his absence Gris gets out of the coffin and leaves. The viewer not only appreciates the difficulty of a workman’s task, as in the prolonged killing in a gas oven in Torn Curtain, but also shares a privileged point of view unknown to the film’s characters. The viewer roots for the vampire’s escape when the worker is away fixing the leaky gas line. The sequence ends as the mortician successfully incinerates an empty coffin. Ironically, his meticulous make-up job does not go up in smoke, but the vampire Gris removes his own stitches in the next scene.

Likewise the creation of suspense through the insertion of humour is evident in the men’s room sequence at the New Year’s Eve party. The idea of a holiday party with dancing, to contrast with the vampiric condition of the protagonist, itself appears inspired by Hitchcock’s narrative stock in trade. Writing on Hitchcock’s Young and Innocent, another British period film, Del Toro observes the prevalence of the party motif:

The scene of the children’s party and the already mentioned ‘long takes’ of the end are the first signs of a dramatic situation that will be repeated many times in Hitchcock’s work: the use of a party, of music and dance (generally associated with the joy of living), in contrast to a terrible situation for the characters or a place appropriate for death and corruption. This association, which had been already outlined in Secret Agent, will be repeated in Rebecca, Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, Rope, Strangers on a Train, The Birds and Marnie. (1990: 172)

In a low-angle shot in Cronos Jesús Gris (Frederico Luppi) as a vampire, licks blood off of the men’s room floor as a man with highly polished shoes walks in.

In Cronos the viewer almost expects Del Toro himself to come out of one of the toilet cubicles, as in a Hitchcock cameo. Instead a husky Mexican man, who actually bears some physical resemblance to Del Toro, does. The clearest gesture to Hitchcock is how the sequence ends, however, with a low-angle shot of Gris licking blood on the men’s room floor, as a highly polished pair of men’s shoes walks by. This close-up recalls the characterisation through close-ups of shoes that opens Strangers on a Train.

Finally the climatic rooftop sequence with the illuminated company logo sign owes much to Hitchcock’s innovative set creations and camera techniques. The showdown scene on high is a staple of Hitchcock thrillers, spanning from Blackmail (on the face of a huge statue) and Saboteur (on the Statue of Liberty), to North by Northwest (on Mount Rushmore) and Vertigo (in the mission bell tower). Although there are other classic allusions at play here, such as the clock sequence in Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936), which point to a critique of capitalism implicit in a death scene on an advertising sign, it is instructive to consider what Del Toro himself comments about how critics have interpreted these Hitchcock sets. Writing on the section on Blackmail, Del Toro cites both Spoto and Leff, noting that in the giant monument chase sequences in Saboteur and North by Northwest ‘the clearest intention is to show monuments erected to honour humanity, which remain indifferent to the human dramas that take place in front of them’ (1990: 108). The giant illuminated sign ‘De la Guardia’ signifies honour only in a virtual, postmodern sense. Although the company is ironically called after a guardian angel, it is indeed indifferent to the human struggle, or morality play that is unfolding on it. The fall of the two characters, Angel and Jesús Gris, from the sign platform and through the roof of the factory recalls the sophisticated set and camerawork that Hitchcock created for Saboteur’s Statue of Liberty sequence. To recall, Hitchcock had a huge model of the Statue’s hand made for the studio. The saboteur is forced to the edge of the statue. He slips off but the hero catches his sleeve, which gradually tears away. Insert shots of the ripping create tension. The fall, which was done with a hydraulic seat for the actor that moved away from the camera, was an example of Hitchcock’s ‘pirotécnica’ or pyrotechnics, as Del Toro calls these innovations. Interestingly Del Toro ‘corrects’ what Hitchcock told Truffaut he saw as a possible defect in that scene, namely that the bad guy falls, not the hero, thus allowing for less identification and hence suspense (Truffaut 1984: 147). In Cronos, both hero and bad guy take the plunge.

In the climactic scene from on high in Cronos the grandfather Jesús Luppi looks towards his granddaughter to make his enemy do the same.

Yet the major difference in the suspense is how the presence of the child Aurora drives the sequence in Cronos. Every glance down in her direction by the two male actors signals cuts in the montage. Hitchcock employed this technique consistently. Telling actors where to look not only was a major element of his directing style, but it famously became an enormous bone of contention with method actors, such as Montgomery Clift or Paul Newman. On the set of I Confess, Hitchcock once told Clift to look up, and Clift, searching for his motivation, immediately asked why. Hitchcock responded with irritation ‘because if you don’t I won’t be able to make my cut’ (McGilligan 2003: 461). In Cronos ultimately, Gris’s look toward his granddaughter makes Angel look down as well. This forced distraction allows Gris the opportunity to jump him. They plummet through the air together and break through the glass roof of the factory. Although Del Toro did not design new hydraulic equipment as Hitchcock did for Saboteur, the breaking roof in Cronos represented an expensive special effect for a Mexican film of its time.

Among directors of Del Toro’s generation, Psycho, ‘the most overly familiar motion picture in history’ (McGilligan 2003: 578), is the Hitchcock film with most universal appeal and influence. Cronos is no exception to Psycho’s pattern of influence. Psycho is embedded specifically in Cronos in its score, which like Herrmann’s creates tension through the use of violins, and in subtle visual allusions to Psycho’s climactic sequence. To recall, when Lila (Vera Miles) discovers Mother’s corpse in the Bates’ house basement, the psychopathic son Norman attacks her dressed as Mother. Shown in an early sequence in Gris’s shop, the head of the antique statue that contains the Cronos device resembles the mummified Mother who spins around in Psycho both in colouration and physical structure. In Cronos, the insects, which attract Gris to probe the statue and eventually find the Cronos device, come crawling out of the deep-set eye socket of the carved statue. The sunken eye sockets are what give Mother her fright power in Psycho.

One of the most distinctive elements of the Psycho basement sequence is the effect achieved with a bare hanging light bulb. Coming into the basement, Lila hits it and sets it swinging. The camera stays on the bulb through its oscillations, which add to the sense of Lila’s disorientation and unease in the situation. Hitchcock insisted on getting a lens flare from the light. The cameraman went through many takes to achieve the flare, which under normal circumstances is generally considered a defective shot. In Cronos Del Toro does not go so far as to use the lens flare effect. However, a swinging bare light bulb figures prominently in the aftermath of the climactic fall sequence and adds to the set’s creepiness. After a black fade, a high-angle shot reveals the broken bodies of Gris and Angel as a single light bulb swings in and out of the frame. A bell-like sound in the score accompanies the motion and tolls for death. The film then cuts to a low-angle shot that shows Aurora, who is symbolically the light herself, approaching her grandfather’s body. Whereas the swinging light bulb disorients Lila in Psycho, the same death image in Cronos does not deter Aurora. She resuscitates her grandfather with the Cronos device she carries hidden in her teddy bear.

Mainstream US critics such as Roger Ebert, who gave Cronos a ‘thumbs up’, did not note the presence of Psycho, or any other Hitchcock film in Cronos, as they did later in the case of The Devil’s Backbone. Rather, Ebert finds Cronos distinctive as a horror film for its religiosity, which he attributes to a Latin culture:

In Psycho when Lila (Vera Miles) comes into the basement to meet Mother, she hits the light bulb and sets it swinging.

Recalling Psycho: in the aftermath of the fall of Angel and Jesús through the glass ceiling into the basement a single light bulb swings in Cronos.

What Latin horror films also have is a undercurrent of religiosity: The characters, fully convinced there is a hell, may have excellent reasons for not wanting to go there. The imagery is also enriched by an older, church-saturated culture, and for all its absurdity ‘Cronos’ generates a real moral conviction. If, as religion teaches us, the purpose of this world is to prepare for the next, then what greater punishment could there be, really, than to be stranded on the near shore? (http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/cronos-1994)

What Ebert sees as ‘Latin’ is the Catholicism whose values Del Toro and Hitchcock shared. Del Toro argues that ethical and moral concerns were essential to Hitchcock’s melodramas:

Chabrol and Truffaut have adapted the rules of the master to their own filmic universes, comprehending that the basis of suspense (understood as the extreme interest of the viewer in a subject that is presented) is sustained with solid and interesting characters, even if they are everyday people, among whom a melodrama of genuine moral and ethical weight is generated, as it always occurs in Hitchcock. The creations of Richard Franklin, Brian de Palma and Spielberg lack this weight, in spite of their enviable use of narrative resources. (1990: 47)

For Del Toro, to create a successful film, and further, to stand above these major directors in the industry, solid characterisation must be accompanied by moral and ethical dilemmas. Cronos presents the moral dilemma of an ordinary man having to choose between living forever as a vampire or causing his own death. We relate to Gris as a caring grandfather and multifaceted underdog. He is savvy enough to take on and play a game with a master of the universe, the industrialist De la Guardia.

Aurora bludgeons the villain to death to save her grandfather in Cronos.

Donald Spoto argues that ‘the added dimension of Hitchcock’s best work – its moral as well as its aesthetic sense’ can only be explained by referring to Hitchcock’s ‘training in Catholicism’ (1994: 504). Spoto illuminates: ‘Hitchcock’s moral sense thus reveals the shallowness of ordinary judgment – for nice people do commit murder. In this regard, the Catholic sensibility triumphs. Everyone is capable of sin’ (1994: 505). Although the granddaughter Aurora in Cronos is not the cultured villain like Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt, it does comes as a shock in Cronos when the final act of violence is committed, abruptly and straightforwardly, by a little girl in a cute red raincoat. She kills the industrialist with the man’s club to save her grandfather. There is no sentimentality in this bludgeoning or in her role overall. All of the characters of Cronos are depicted as cultured and refined. Federico Luppi, who plays the protagonist/vampire/antiques dealer Gris, is known for an on-screen presence of dashing elegance. Even the supporting characters, such as the heavy/nephew (Ron Perlman) who is intent on choosing the right profile for his nose job, are striving to move up in the world through makeovers. Regarding the paradoxical role of aesthetics, Spoto is accurate to point again to Hitchcock’s Catholicism: ‘the director’s Catholic roots and deep moral sense as an artist insisted that the split in style and act (elegance versus crime) was the clue to the fragility of the human condition’ (ibid.). Del Toro not only understands this point of view, but also puts it on the screen in Cronos.

III. THE HOLLYWOOD GENIE OUT OF THE BOTTLE: FROM THE BIRDS TO MIMIC

After the international critical success of Cronos, Guillermo del Toro was offered contract work in Hollywood to direct scripts of film projects, especially horror films, already under way. He turned them all down, including the fourth installment of the Alien series.9 Interestingly he did collaborate with John Sayles on the script for Sayles’ Spanish-language film Men with Guns (1997). He also helped Sayles contact Federico Luppi to star in his film. In the meantime four of Del Toro’s own treatments for science fiction films were rejected in Hollywood until his treatment of a story by Donald A. Wolheim about a mutant species that attacks humans was accepted. Mimic tells the story of Dr. Susan Tyler, played by Mira Sorvino. To halt the spread of a deadly disease, she genetically fashions a new species of insects out of cockroaches, beetles and flies. Although the creatures are supposed to be sterile, they reproduce and become monster bugs when she releases them into subterranean New York. Their scariest trait is that they mimic humans. An autistic child Chui (Alexander Goodwin), son of a shoemaker, in turn mimics their sounds on the spoons he plays with. As they are pursued through the subways, in the course of the film the bugs devour the boy’s father, as well as many members of the NYC police. Finally Susan’s husband Peter (Jeremy Northam) sets off an explosion that annihilates most of the insects. When the crucial male insect threatens the child Chui, Susan distracts the monster bug by cutting herself. The male bug is then run over by a train, which ends the insect plague. Susan, her husband and the orphaned Chui are reunited above ground in the film’s final tableau.

As with Cronos, Mimic is about letting the insect genie out of the bottle. Ironically, these bugs became much more complex and more independent than Del Toro wanted. One has to remember that Mimic was given its go-ahead in the shadow of Jurassic Park (1993), which wowed audiences with its computer-generated/digital dinosaurs. Hollywood always wants to remake its last success. Although Del Toro himself had done the drawings for the mutant insects, the Hollywood production model metaphorically let them get away. The Spanish critic Quim Casas describes Del Toro’s disappointment with his first foray into Hollywood as if Hollywood itself were Mimic’s underworld of giant insects:

Mimic can be seen as a practical experience of apprenticeship in the twisting and slippery territories of Hollywood. Del Toro didn’t like how the movie ended up, since his intention was to make a B movie with much simpler giant insects than the investors finally decided on. Since then he does not work with a designated second unit, thus taking charge of everything that is filmed in his movies. (2004: 50)

Nonetheless, Casas argues that Del Toro did still succeed with Mimic in making a B movie as he originally wanted:

The B movie series is not only a particular aesthetic of cheap production, sets that stand out, bad actors, abbreviated narrative forms and imaginative shots, but also a quality, a concrete manner of dealing with the cinematographic story. In Mimic Del Toro is closer to it than to the Hollywood fantasy movie of high production values.

In contrast to his movies in Spanish and Hellboy, in Mimic the characters lack dramatic, or authentically coherent, hooks. They could be called minor, in terms of how their basic characteristics are sketched out, compared even to that Blade that was about to enter into Del Toro’s domain. In this manner the film also resembles certain B movies, although it isn’t consistent in drawing the connection simply in one stroke. The protagonists of the film wander aimlessly under the asphalt, ambushing, attacking, defending themselves or surviving in the ventilation ducts, the sewers, the abandoned subway cars and the rust of the iron labyrinths that served to run the subway, but which now are the home of mutant insects. (2004: 52)

For Casas, minimal characterisation in Mimic – often the lack of ‘agarraderas drámaticas’ or dramatic hooks – distinguishes the film from Hollywood’s grand productions. Since Casas points to characterisation as the critical element where Del Toro expresses an authorial perspective, that of a B film, in Mimic, it is worth exploring this aspect of the film in the context of Hitchcock.

Along with Pan’s Labyrinth, Mimic is the only one of Del Toro’s films with a female protagonist, although Marisa Paredes in The Devil’s Backbone, and Leonor Varela in Blade II, come close in their supporting roles. Of all the casting choices for Mimic, US critics most faulted that of Mira Sorvino as Dr. Tyler. James Bernardinelli finds her ‘miscast’ compared to her previous roles, arguing that ‘maybe the problem is that she’s so good at playing bimbos (as in Mighty Aprhrodite and Romy and Michelle’s High School Reunion) that it’s hard to accept her as an egghead’ (http://www.imdb.com/reviews/84/8497.html). He neglects to mention that Sorvino played Marilyn Monroe in Norma Jean and Marilyn (1996) the year before Mimic. All these ‘bimbos’, of course, are blondes. Is there a Hitchcock blonde here? In fact, yes. Sorvino’s casting can be appreciated as an updating of Hitchcock’s female icon. Mimic’s plot recalls The Birds in which Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren) is seen as responsible for unleashing a freak of nature, albeit above ground. Indeed, the culpability of Melanie in unleashing the plague of birds in Santa Rosa has long been one of the most debated aspects of The Birds. Her sexuality, symbolised by the lovebirds, which she secretly drops off at Mitch Brenner’s ranch, is often portrayed as the catalyst for the avian plague. Although Janet Maslin (1997) in her New York Times review faults Mimic for general lack of motivation in characterisation, she is one of the few critics to note the irony of Dr. Tyler and her husband having trouble conceiving children while ‘Susan’s malevolent bugs spew fecund foam beneath the Delancy Street subway station’. Dr. Tyler in Mimic is the sexually frustrated, and by extension, culpable catalyst of nature in Mimic as Melanie was in The Birds.

Melanie Davis (Tippi Hedren) on her way across Bodega Bay to drop off a pair of lovebirds at Mitch Brenner’s (Rod Taylor) ranch in The Birds.

Not surprisingly, Del Toro is a big fan of The Birds:

The Birds is Hitchcock’s most spectacular movie, one of the most impressive technical and filmic exercises in all of film history and the perfect narrative and thematic continuation of the most sophisticated Hitchcock of Psycho.

Within his ‘catalysing’ cycle, the film takes the obsession that Hitchcock felt for birds as ‘heralds of chaos’ (Spoto’s words) to its perfect conclusion. They are used in a fitting manner that brings to bear upon human beings the ultimate and grandest evidence of their coexistence within chaos itself. (1990: 425–6)

As we have seen, Cronos alludes frequently to Psycho, hence The Birds, Hitch’s next film, appears as a logical pattern to follow for Mimic. As Del Toro notes, Hitchcock settled on The Birds after the studios rejected three of his suggested projects, a situation similar to what happened to Del Toro’s first four proposed treatments in Hollywood. Both films are essentially nature parables.

Yet it is in the treatment of the female role in particular that Mimic resembles The Birds. Scientific authority in a female voice was already envisioned in the role of the amateur ornithologist Mrs. Bundy (Ethel Griffies) in the diner sequence of The Birds. She carries the lengthy expository scene as she lectures on birds while others speculate on the reason for the bird attacks. In Mimic Dr. Tyler is a similar voice of authority in an early sequence in which she presents her Judas strain of insect in a press conference. Not surprisingly either, the feminist critic Camille Paglia in her BFI monograph on The Birds (1998) finds the film’s meaning in the role of woman’s power in the ‘nature parable’. This is evident in her reading of the film’s publicity campaign:

Female voice of authority in The Birds: Mrs. Bundy the ornithologist (Ethel Griffies) lectures Melanie and the other diner patrons on birds.

In a print ad, Hitchcock tried sexual innuendo: ‘There’s a terrifying menace lurking right underneath the surface shock and suspense of The Birds. When you discover it, your pleasure will be more than doubled.’ It’s the familiar Shakespearean paradox of shadow versus substance, but for Hitchcock the menace is archetypal woman, who is the mistress of surfaces.” (1998: 88)

Paglia notes that Tippi Hedren as the protagonist Melanie Daniels was probably unjustly criticised in reviews of the time because in making her debut, Hedren represented a new sensibility in the line of Hitchcock blondes. This freshness is what comes across in the casting of Sorvino as Dr. Tyler in Mimic, too. Overall, Paglia views The Birds ‘as a perverse ode to woman’s sexual glamour, which Hitchcock shows in all its seductive phases, from brittle artifice to melting vulnerability’ (1998: 7). Mimic is by no means about fur coats and nail polish – wardrobe elements that Paglia analyses. However, Eve’s responsibility for chaos is critical to both films. Mimic makes this connection clear in an early scene at home between Dr. Tyler and her husband right after the viewer has just seen some of the first giant bugs. As her husband plays the piano, he tells her she is responsible for the insect plague: ‘They were designed to die; they are breeding.’ In The Birds when Melanie comes to dinner at Mitch’s house, she sits down to play the piano. Shortly thereafter, birds invade the house by swarming down the chimney.

In reading the ‘psychological dynamics of the finale’ Paglia sides with Margaret M. Horwitz’s view:

Lydia certainly appears ‘victorious’ and that she and the birds have ‘achieved dominance’. It’s like the Pompeiian wall panels of the Villa of the Mysteries, where the exhausted, flagellated acolyte buries her face in the receptive maternal lap: rogue vixen Melanie has been whipped back to her biological place in the pecking order. Horwitz sees Melanie’s eclipse in the film’s treatment of her car: first, it gives her the ‘power to come to Bodega Bay’, then Mitch ‘ends up driving it’, and finally she’s ‘banished to the back seat’ – becoming one of two children to Lydia as mother and Mitch as father (and Oedipal son). (1998: 86)

In Mimic’s finale, Dr. Tyler is similarly shunted aside by her husband. Crawling out of the crater of the explosion, in a last suspenseful revelation, he resurrects the family Trinity and reasserts a conventional dominance as he towers over Susan and Chui in their embrace. The blessing of the absent father, Chui’s dead father, is silently given in the sign of the cross, the shoemaker’s necklace draped over the new father’s back.

Many other Hitchcockian motifs are prominent in the film. The child Chui always identifies beings, human or a mimicking insect, according to their shoes. The deadly male insect is ‘Mr. Funny Shoes’, for example. Chui’s obsession with men’s shoes, though logical for the son of a shoemaker, and a humorous touch, also alludes to the opening of Strangers on a Train, which characterises the main characters by close-ups of their shoes. The sinister, yet dapper protagonist Bruno will always be known for his ‘funny’ two-tone shoes. Other motifs from Strangers on a Train also find inventive new uses in Mimic. One of the famous shots of Strangers on a Train is of Miriam’s glasses that fall and break when she is strangled by Bruno. In Mimic, the shoemaker’s glasses fall off when he is devoured by a giant insect. As in Strangers on a Train, the glasses are all we see of the brutal killing of a major character. But in Mimic, Dr. Tyler’s husband picks them up and later uses them to complete the electrical circuit in an abandoned subway car and to enable the trapped good guys to escape.

In The Birds’ family scene finale, beaten down Melanie is put in her subservient place in the arms of mother Lydia (Jessica Tandy) in the back seat of the car.

In Strangers on a Train the shot from within a storm drain creates extra suspense as Bruno (Robert Walker) drops and tries to retrieve the incriminating lighter.

Finally, in Mimic we begin to see Del Toro imitating some of Hitchcock’s classic techniques and motifs to create suspense.10 This is especially prominent in scenes with lighters. The archetype is the sequence in which Bruno drops his purloined lighter down a street grate in Strangers on a Train. It falls further from his grasp as he tries to retrieve it. The viewer is dying with suspense as she watches Bruno’s efforts from a shot from within the storm drain. In Mimic’s ending in subterranean New York, Peter opens a gas line and tries to get his lighter going to create an explosion, but the lighter – shall we say, predictably – falls out of his grasp. The film cuts to a shot showing the lighter from below, just as in Hitchcock. Mimic, however, adds extra suspense, for the lighter appears to fall through water, which we think will eliminate the possibility of a saving explosion. Hence, the big final blow-up comes as even more of a surprise.

In conclusion, interpreting Mimic in the context of Hitchcock’s The Birds sheds light on the role of gender in the film, which critics have disparaged or simply overlooked in Mimic, as well as the importance of religion in the film. Del Toro’s interpretation of The Birds, in which chaos is the sign of divine intervention, forefronts the shared Catholicism of the works of the two directors. This convergence is especially evident in the prominent place of Catholic religious symbols in Mimic’s finale. The dead shoemaker’s cross necklace adorns the new family, survivors of the explosion, as a blessing from God. Also, we have seen how Mimic exploits and reintegrates in its own discourse of suspense significant Hitchcock leitmotifs, particularly of glasses and lighters from Strangers on a Train. Unquestionably, the presence of Hitchcock’s work in the narrative and mise-en-scène of Mimic shows that it supported and enabled Del Toro’s transition between his first Mexican and US films.

IV. FROM HITCHCOCK’S ‘DUALITY FILMS’ AND PSYCHO ‘S SWAMP TO THE DEVIL’S BACKBONE

After Cronos Guillermo del Toro wanted to make The Devil’s Backbone in Mexico as his next project, but he found it difficult to get funding for the film, so went ahead with Mimic. In an interview with Gabriel Lerman in Dirigido after Mimic’s release in Spain, Del Toro discussed how the obstacles he was encountering to get The Devil’s Backbone underway impacted his long-term career plans. To Lerman’s suggestion about the difficulties of filming in Mexico, ‘but perhaps it may be more difficult to continue filming in Mexico’, Del Toro replied:

I don’t think so. My long-term plan is to be able to become sufficiently prestigious so that people recognise my name. Then I’ll be able to make a movie in Mexico and nobody will care if I film it in Spanish or English … When the time comes I’m sure that there’ll be people who will put up the necessary funds. I don’t want to make a $30 million movie in Mexico, I want to make a movie that lets me have the freedom that $2 million or $3 million gives. I want to have, whenever possible, total autonomy. (1997: 52)

When later Lerman asks why he wants to film in Mexico, Del Toro argues strongly for cultural specificity:

Because the stories one tells have particular characters that belong to specific places. I know that I can’t tell the story of Mimic in Mexico the same way that I tell it in the United States so that it has the same characteristics. There are things in Mimic that are simply North American and Anglo-Saxon. The traits of the characters from The Devil’s Backbone are exclusively Mexican, and have a very Latin American magic about them. In this film that I’m about to shoot there’s going to be a kind of festival of colours and sensations that I can only get in Mexico. (ibid.)

This Mexican folkloric festival, however, never happened. He never could get sufficient backing for the film in Mexico. Moreover in 1998 his father Federico del Toro, an automotive entrepreneur, was kidnapped and held for ransom in Guadalajara, a situation that was still not resolved when he and Bertha Navarro arranged to meet Pedro Almodóvar at the Guadalajara International Film Festival (see Cruz 2008: 49). Del Toro later negotiated his father’s release, but he himself continued to receive death threats, which forced him into self-imposed exile, primarily in California, for the safety of his family. He stated that because some of the criminals responsible for his father’s kidnapping were never caught, he could never film in Mexico again, only act as a producer of others’ projects there.11 For The Devil’s Backbone he took up the co-production offer from Almodóvar’s El Deseo company, whose terms meant filming in Spain with a Spanish crew. Respecting cultural specificities, he rewrote the script and transposed its original backdrop of the Mexican Revolution to the Spanish Civil War.12

Although this new alliance of Almodóvar/Del Toro was much commented on in the press of the time, their common admiration for, and mining of, Hitchcock’s work went unnoticed. As this book demonstrates, there is a significant, defined class of Latin directors inspired by Hitchcock. The association with Almodóvar’s production company, which produced films by Álex de la Iglesia, Daniel Capalsoro and Guillermo del Toro, also links a significant number of them.

The Devil’s Backbone, which was released worldwide in 2001, is a ghost story. It tells the story of a boy Carlos (Fernando Tielve) who is left at an orphanage near Madrid supposedly to protect him from the Spanish Civil War. The orphanage is run by a pair of Republican sympathisers, Dr. Casares (Federico Luppi, again) and Carmen, the directress with a Buñuelian prosthetic leg, played by Marisa Paredes, known for her work in Almodóvar’s All About My Mother. Jacinto, the young caretaker and Nationalist sympathiser, who is the heavy of the orphanage’s staff, is played by the Spanish heartthrob Eduardo Noriega, known from Almenábar’s Open Your Eyes and Thesis. Jacinto has sex with the directress in exchange for one of her keys with which to try to open the orphanage’s safe. The safe contains some of the fabled Republican gold bars, which act as the film’s ‘Macguffin’. Dr. Casares has his own cache. He keeps foetuses with prominent spines pickled in huge glass jars. Drinking the liquid from the jars, as Casares does, fortifies the brave imbiber with the devil’s backbone. Del Toro explains the title: ‘Devil’s backbone is essentially poverty and disease, something that destroys childhood’ (DVD commentary).

By talking with the other boys and studying a book of drawings by one of them, the new boy Carlos gradually discovers that a young boy Santí (Junio Valverde), who died under mysterious circumstances, haunts the orphanage. When Carlos sneaks into the kitchen to get water one night, Santí scares him with his appearance. Jacinto later beats Carlos for the night-time intrusion. Jacinto, himself an orphan, is caught by the directress trying to steal the gold hidden in the orphanage’s safe and is expelled from the orphanage. He sets the building on fire and flees in a truck with some of his buddies. The directors die as a result of the confrontation and Jacinto and his cronies set siege to the orphanage. The boys rally to defend it. In a tableau that echoes Mother in a chair in Psycho’s basement, they position the dead director’s body with a gun in a visible window to scare off Jacinto and partners. Though finally abandoned by the other men, Jacinto takes possession of the gold and wears it around his belt. He and the boys confront each other near the cistern pool. Jacinto is wounded and falls into the pool. Refusing to let go of the gold, he is pulled under the water by Santí’s ghost. With this vengeance behind them, the boys set out on the road away from the orphanage.

Of all of Del Toro’s films, The Devil’s Backbone is the one in which Hitchcock’s motifs, desire for innovative pyrotechnics and narrative structure are most strongly apparent.13 The film is an ode to Hitchcock. The evidence for this is clear and convincingly presented by Del Toro himself in his ‘maiden voyage into DVD commentary’, the voiceover track made in excellent conversational American English for its US release. Early on in the commentary Del Toro explains that he owes the narrative structure to Hitchcock’s duality films:

This is the movie I made I love. One of the reasons is because it was structured in a free environment. The movie is constructed like a rhyme, something I have been trying to do for many, many years. The movie opens and closes with similar images and a similar epilogue and prologue. In the movie we will be quoting many images in pairs. This comes from me watching and enjoying the duality films of Alfred Hitchcock, where in order to establish a certain rhythm in the poetry of a movie and a certain commentary in pairs, like Shadow of a Doubt, Suspicion, Strangers on a Train, where duality is important, he would repeat and quote himself, and quote situations. Like this image, for example, the kid kneeling or crouching by the water will be repeating much later with another character for the purpose of being resonant.

Indeed the basement scenes by the cistern pool, which begin and end The Devil’s Backbone, function like Psycho’s swamp. To recall, the final image of Psycho is of Marion’s car being pulled out of the pond.

Given that his director of photography Guillermo Navarrro accompanies Del Toro for the DVD commentary, many remarks concern the lighting and mood of the picture. Del Toro faced a challenge for The Devil’s Backbone in central Spain near Madrid similar to that Hitchcock faced for The Birds in the bay area of northern California – how to deal with an area ‘drenched in sun’ to create a mood of horror. In choosing to introduce the ghost Santí in midday light in the courtyard door, Del Toro makes a gesture to Hitchcock’s spirit of poetic, and finally technical innovation. In The Birds the first time a bird attacks Melanie she is out in a motorboat on the water in broad daylight.

The colour of the sky was subdued in the post-production lab to get the right effect (see Paglia 1998: 19). As Del Toro writes:

The ghost Santí appears in broad daylight in the courtyard doorway of the orphanage in The Devil’s Backbone.

In The Birds the first bird attack is against Melanie as she crosses the sunny Bodega Bay.

Much has been said that it’s in the horror genre where an artist free of the ties of ‘the real’ can create his purest reflection about the world, approaching what in literature is the equivalent of poetry. The Birds is the only horror film (in the most fantastic and purest sense of the term) that Hitchcock made. It’s his film of the freest conceptual and artistic creation. (1990: 432–3)

Another example of the ‘construction in pairs’ is the repetition of a shadow on a curtain, done with digital effects as discussed in the DVD commentary. In noticing the shadow without an object to cast it, Carlos senses Santí’s presence near his bed in the cavernous orphanage dormitory, first in an early sequence, which is later repeated. For Del Toro, these poetic images, The Devil’s Backbone’s shadows, and those in The Birds, ‘succinctly define what it means to be human’. In both films to be human means the ability to receive and interpret sensations. The frequent use of strong expressionistic shadows in The Devil’s Backbone recalls moreover Hitchcock’s Germanic tutelage so evident in his British period, which Del Toro both admires and defends.

Another one of Del Toro’s Hitchcockian ‘dualities,’ which link formal and symbolic elements, concerns a camera movement associated with classic 1930s films. Moving between two rooms of a set, the camera shows the set wall in its transition, and thus violates the illusion of reality. (Almodóvar used this movement to great success in the bedroom scene of What Have I Done to Deserve This?) In The Devil’s Backbone Dr. Casares declaims love poetry to his mirror on the wall in his room. The camera moves parallel to the set, showing the wall between his room and that of the directress. The wall symbolises his unrequited love for her. Reprising the motif of unrequited love, Casares will later recite Tennyson to her as she lies dying in the aftermath of the explosion. Yet in this initial scene with the wall, we move around the wall between their two rooms to an equally brutal scenario. We see Jacinto having violent sex with her to get a key to access the gold. Del Toro says: ‘I wanted the key, being a fan of Hitchcock. I always loved the way he did the huge crane in Notorious with Ingrid Bergman with the key to the cellar.’ While his comment about the key reaffirms the importance of Hitchcock to the interpretation of this sequence, the filmic transgression, of showing the artificiality, the theatricality of the set, is far more significant. Hitchcock, in showing, for example, an obviously fake set wall at the end of Marnie, for which even Almodóvar criticised him, pushed the boundaries of filmic discourse to their limits, made the spectator aware of them without losing her interest in the narrative. The Devil’s Backbone, in the use of a retro camera movement, revels in the history of film, and especially in Hitchcock’s place in it, and in the artificiality of the medium.

Subtle moodiness in The Devil’s Backbone is achieved by expressionistic shadows and digital particles that signal the ghost’s presence, but also through measured yet free-moving camerawork that allows for most information to be gradually transmitted visually to the spectator, rather than through dialogue. The camera functions as another witness. Like Hitchcock, Del Toro implicates the spectator. He shows us the elements for an explosion, to cause suspense, before the explosion occurs, as in the case of the gas cans in the orphanage, or in the case of the bomb in the courtyard, which never does explode. Another good example of this well-paced visual reveal is how the presence of Dr. Casares helping an injured boy is shown, even after Casares has died, and hence is another ghost. We only see Casares’ handkerchief on the hall floor but know that he, and metaphorically, the good guys too, live on in good deeds. Likewise in Hitchcock’s Rope, the hat of the murder victim left behind is discovered, and reveals the presence of the body in the apartment.

In his DVD commentary to the sequence in which huge crosses and paintings are hauled out and displayed in the orphanage, Del Toro is defensive about the interpretation of the presence of religious imagery in The Devil’s Backbone:

Conchita (Irene Visedo) receives ‘a grain of strength’ vitamin from an orphan as if it were a communion wafer before she sets off to seek help in The Devil’s Backbone.

Most people think it is me and my Catholic obsessions. No, as the Fascists came back and wanted to reign in Spain, the Republicans put up religious imagery to say to leave them alone.

While the information is historically accurate, his choice of this material, as well as that of the teacher Conchita (Irene Visedo) giving daily vitamins to the orphans as if they were communion wafers saying ‘un granito de fuerza’, or ‘a grain of strength’, as she places them on their tongues, argue precisely for the perception of Del Toro as a director ‘obsessed’ with Catholicism. The importance of the vitamin communion is stressed by its being repeated, inverted, when an orphan gives her a vitamin before she sets off to seek help after the building has been torched. On the road Conchita encounters Jacinto who stabs her to death. Her death is hence framed as martyrdom. Del Toro and Hitchcock wove numerous Catholic motifs into their films with full understanding of the Catholic worldview. In The Devil’s Backbone the jars of foetuses are a crucial image of visceral, political unease of our age. The Catholic Del Toro calculated their effect well.

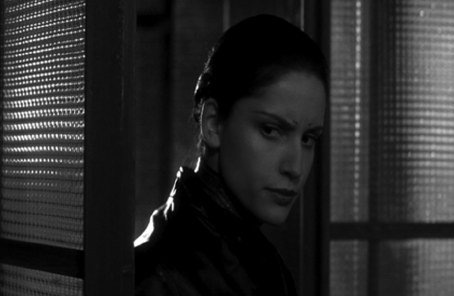

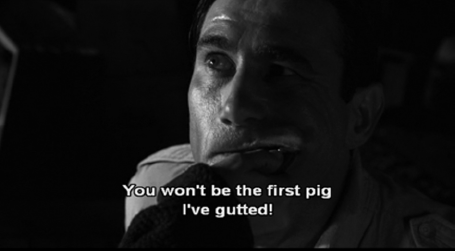

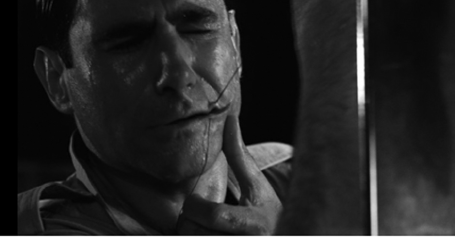

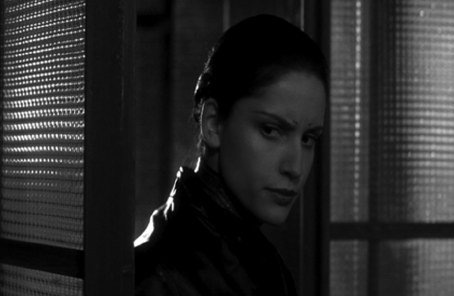

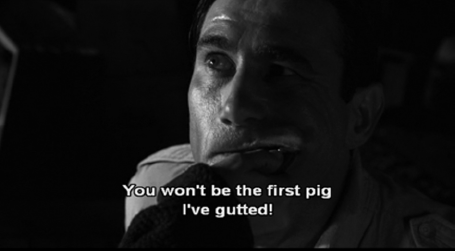

The Devil’s Backbone does not shy from the representation of violence, nor did The Birds, or Frenzy. Del Toro’s ‘walk out scene’ merits discussion in the context of terror techniques. He calls the sequence in which Jacinto cuts Carlos’s face as a punishment for trespassing in the kitchen ‘a walk out’ – that is, ‘anybody who isn’t with the movie is going to walk out’ (DVD commentary, The Devil’s Backbone). He is aware of transgressing a taboo, which is especially strong in Hollywood, to actually show violence against children. Analogously, a ‘walk out scene’ for Hitchcock would be the sordid strangling sequence of Frenzy, one of Del Toro’s favourite Hitchcock pictures due to ‘precisely the film’s “bad taste”’ (1990: 463).14 As in the case of the directress’s prolonged death later in The Devil’s Backbone, Del Toro’s half-in-jest remark applies here, too: ‘As a Catholic fat boy, I like the characters to suffer’ (DVD commentary, The Devil’s Backbone). The film represents Jacinto consistently throughout as someone who can only communicate through violence. Casting the ‘teenage idol’ Noriega against type as Jacinto – ‘the equivalent of having Brad Pitt play a psychopath’ – follows Hitchcock’s effective lead of casting the handsome Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates in Psycho.

The ‘walk out’ moment in The Devil’s Backbone: Jacinto cuts Carlos’s (Fernando Tielve) face with a knife as punishment for trespassing into the kitchen.

In conclusion, many other techniques and motifs associated with Hitchcock’s suspense vocabulary, such as the reverse tracking/forward zoom Vertigo shot, the distinctive violin sounds of Psycho’s soundtrack, and the placing of the dead body of Dr. Casares in a chair for a scare like Mother’s in Psycho, are also used in The Devil’s Backbone. Yet what is most significant about the film is Del Toro’s acknowledgment that he constructed it with Hitchcock’s poetic ‘rhythm’ in mind. The sounds of that ‘rhythm’ are convincingly there in the film – in the digital innovations that indicate the ghost’s presence, in the implication of the spectator through the camerawork, and in the suggestive symbolism, Catholic and otherwise, through the film.

V. A GLOBAL MIX OF LOVE AND ADVENTURE: FROM NORTH BY NORTHWEST AND ROPE TO BLADE II

When the Spanish critic Antonio Santamarina reviewed The Devil’s Backbone in Dirigido, he ended with a pessimistic forecast: ‘Unfortunately the new scheduled stopover for Guillermo del Toro in Hollywood, for the filming of Blade II, doesn’t promise great results’ (2001: 24). Many people were indeed surprised that Del Toro took on the sequel to Blade (1998), based on the eponymous Marvel comic book hero, in which Wesley Snipes was set to reprise his starring role. Since critics worldwide had overwhelmingly panned director Stephen Norrington’s work on Blade, it was not surprising Hollywood was looking to revive the property with a change in director. But given that Del Toro had complained of loss of creative control on Mimic, his last encounter with Hollywood, it would seem he had learned his lesson and would duck those swirling blades this time. The fact that David Goyer, scriptwriter on Blade and The Crow (1994) who would become director for the third installment Blade: Trinity (2004), was already contracted to write Blade II when Del Toro was approached also augured for significant limits being placed on Del Toro’s creative input. The likelihood that Blade II would catapult Del Toro’s name into positive blockbuster recognition was not great. What happened to that auteur talk he fed Dirigido’s Gabriel Lerman about The Devil’s Backbone and his ‘freedom’? Why take on Blade II then? Money must have spoken loudly. But his longtime attraction to comic book and fantasy art was also right up there. Finally, the character Blade, also called Daywalker because he is half-man, half-vampire, represented a return to the themes and genre tropes Del Toro had spent years mulling over for his debut vampire film Cronos.

Blade II introduces a new breed of vampires called the Reapers, who prey on both humans and vampires. In Prague a downtrodden man with a cleft chin, the sign of the Reapers, goes to give blood for money at a clinic, which recalls all fascist fantasies about dental torture. He, however, opens his jaws wider than any of them and devours his tormentors instead. Meanwhile, also in Prague, Blade (Wesley Snipes) tracks down his partner/father-figure Whistler (Kris Kristofferson), whom the old-style vampires captured and supposedly killed in Blade. He rescues Whistler from a huge tank of water that looks like a game show booth. Back at their home base, they are accosted by two vampire visitors with bug-like masks, Nyssa (Leonor Varela) and Asad (Danny John-Jules). These messengers from the vampire king Damaskinos (Thomas Kretschmann) seek to enlist Blade’s help in combating the Reapers. Blade joins an alliance with their squad, called the Bloodpack, led by Rheinhardt (Ron Perlman). The Bloodpack enter the disco-like House of Pain where they engage the Reapers in a subterranean fight scene. Afterwards Nyssa performs a memorable autopsy on a twitching Reaper to show both how quickly they rejuvenate and where their only vulnerable point is. Many explosions and martial arts scenes reminiscent of The Matrix (1999) later, several major characters – Blade’s new sidekick Scud (Norman Reedus), and Damaskinos’s son (Luke Goss) – go over to the darker side of the Reapers. Nyssa and Blade are ever more attracted to each other, especially as she sees him saving her in battles. Damaskinos’s son betrays and kills his father. Nyssa confronts her brother and is bitten by him as well. Then in an act of self-sacrifice she asks Blade to take her out into the light so she can die before she is transformed into a Reaper herself. Blade, or Daywalker, who himself has the special power to resist light, carries her in his arms toward the sunrise until she is vapourised by the dawn’s rays.

When Blade II was released, Del Toro proved sceptics wrong. Most critics and audiences found that he had been up to the challenge. Even Mark Holcomb (2002) of the Village Voice, who found the film fell short of Del Toro’s ‘whip-smart revisionism of Cronos’, joined others in making puns about ‘breathing new life’ into the Blade franchise. Pam Grady of Reel.com states the general opinion: ‘[Blade II] only means to entertain, and that it does’ (22 March 2002). Del Toro finally succeeded in making his B movie in Blade II and it gave him the credentials to take on Hellboy.

There is little in Hitchcock’s 53 films that come anywhere near the vampire genre or the comic book adaptations of Blade II and Hellboy. The legendary editing of the crop-duster chase scene in North by Northwest, as evidence of Hitchcock’s skill with adventure tropes, or his pacing, and creation of suspense in the gas station explosion sequence of The Birds, can only go so far as a basis for comparison. Truly Del Toro’s work, and Del Toro’s Hollywood, is that of another generation, marked more by the technological revolutions of George Lucas’s Star Wars series (1977–1983). Yet there are ‘big picture’ comparisons, especially lessons about auteurship and cinematic style, which derive implicitly from Del Toro’s study of Hitchcock’s career. Reviewing Hellboy in Dirigido, Quim Casas argues that Guillermo del Toro is unique among his generation of directors without borders in achieving a ‘coherencia interna’, or ‘internal coherence’, throughout his work in three major industries (2004: 46). ‘Internal coherence’ is in fact synonymous with auteurist cinematic vision, which definitely manifests itself in Del Toro’s work. Looking at Del Toro’s career chronologically then, the jump from The Devil’s Backbone to Blade II, or the disjunction between these projects, from the small-budget Spanish/Mexican film to the Hollywood megabudget action flick, is where the concept of his auteurist vision is most directly challenged. Importantly, it is also where the notion of a new global auteur is reaffirmed. Hellboy, so close in genre to Blade II, can almost be seen as part of the Blade series.

The location of Blade II announces the global ambitions of the film. Blade II was set and partially filmed in Prague, something the critic John Berardinelli found strange.15 How strange not to recognise it as near the homeland of Dracula, and if we are talking contemporary global politics, also as one of the vibrant cultures of the new Europe? It is significant that Del Toro sets the House of Pain, Blade II’s party scene, in Prague. As we noted with respect to Cronos, the presence of a party scene, to establish the parameters of good and evil and create a sense of foreboding, was a Hitchcock narrative staple. Moreover, the club party scene that opens the first Blade was its most memorable, and for some, its only acclaimed sequence. In the vampire club/American slaughterhouse, blood sprays out of the sprinkler system as the dance music peaks. Blade II repeats the vampire party topos in an urban European environment. The House of Pain sequence begins with a joke about exclusivity. Blade cannot see the vampires, or find the nightclub on the city street until Nyssa hands him special glasses that make vampire markings, or graffiti, visible.

The film’s global pretensions are also apparent in its language mix. It has snippets of subtitled dialogue when some vampires speak, presumably in Czech, and also in Russian. American English dominates the picture, as it does the current world. To recall, Del Toro tried mixing languages to enhance characterisation in Cronos.16 He now carried these ideas forth to Hollywood’s Blade II.

Despite an immense difference in pacing or overall rhythm between the languorous The Devil’s Backbone and the video-game zapping of Blade II, the visual conceptions of these apparently disparate films have much in common. Moreover, the visual concept of Blade II departed radically from Norrington’s Blade, in a manner particularly consistent with Del Toro’s Catholic background, a trait, to repeat, he shares with Hitchcock. The initial film imagined the character Blade in Egyptian or biblical settings. For example, in a climactic sequence when the vampires drain Blade’s blood, they half entomb him standing up as if he were King Tut on display in a museum. Del Toro’s fantasies in Blade II, on the other hand, look Roman, if not Roman Catholic. Recalling The Devil’s Backbone’s orphanage basement, numerous sequences of Blade II are set in underground catacombs, such as the rotunda of the purebred vampires. On the DVD commentary track to Blade II, Del Toro calls Damaskinos’ chamber a ‘Roman Age ruin’. Elgin marble-like carvings serve as backdrops to his indoor pool of blood, which recalls The Devil’s Backbone’s cistern. Furthering the sense of mystery, as did the cavernous orphanage dormitory in The Devil’s Backbone, most of the large sets of Blade II resemble church interiors replete with high-placed coloured windows. When Blade prowls and engages in a fight on scaffolding which bisects the interior of a church, the very scale of the space questions Blade’s vulnerability, just as in The Devil’s Backbone it defined Carlos as an orphan and challenged his will to explore.17 The visual consistency, of depicting monumental, symbolic spaces, with religious overtones, is a consistent component of Del Toro’s auteurist vision. Giving it his usual mark of authenticity for the movie’s freely conceived mise-en-scène, the Blade II sequence was filmed in an actual church in Los Angeles.

The Elgin marble-like carvings, as in a ‘Roman Age ruin,’ serve as backdrop to Damaskinos’s (Thomas Kretschmann) indoor pool of blood in Blade II.

Blade (Wesley Snipes) prowls over the scaffolding that bisects the interior of a church in Blade II.

Yet, like Hitchcock’s films, Blade II works not just because of the monumentality of the sets, but because viewers can understand and care about the film’s story through a savvy handling of adventure and melodrama. The movie-going experience is about the gore and the cool vagina dentata-style innards of the new breed vampires, but Blade II works because it is balanced by small sequences that involve the spectator in identification. For example, the film crosscuts between confrontations of vampire bands in the catacombs, resembling war platoons in action, to shots of the geek Scud (Norman Reedus) in his surveillance van outside. We are that guy with the box of doughnuts looking in on the wars and fighting private fears of the invading vampires. Taking Scud’s almost safe position acknowledges that the viewer is conscious of, if not in control of the technology. Furthermore, the presence of the intimate closed space helps the viewer connect to the epic scenes. The interplay is made even more memorable by Blade’s unmasking of Scud later in the film as himself both vampire and mole. Del Toro pulls us into caring again through an interplay of scale and a wink to his auteurist vision, which he laid out in Cronos. Ron Perlman, the goon-like nephew in Cronos, plays Reinhardt, a vampire ringleader in Blade II. In an early sequence Blade implants a small detonator, a Cronos-like pronged device, on the back of Reinhardt’s head to control and threaten him. In the revelation sequence, Reinhardt flings the device off, calling it, and thereby Blade’s powers, fakes. When Reinhardt tosses the device, Scud catches it in his hand. Taunting Blade even more fiercely than Reinhardt did, Scud reveals he is a mole and traitor. The device digs into Scud’s hand, à la Cronos device. Reasserting his power for good, Blade activates the device and blows Scud to bits.

In his almost safe spectator’s position the geek Scud (Norman Reedus) eats his doughnuts in a surveillance van in Blade II.