The fortunes of war are fickle and varied and the outcome of battle is most often dictated by the quality of the most basic component – the soldier. Whether commander or infantryman, the fate of nations can depend on his performance on the battlefield. The war on the Golan was just such an encounter with the survival of the state of Israel at stake. Although few individual actions can be genuinely considered fundamental to the outcome of a battle, there are particular decisions and particular events that can tip the balance. Predominantly it is the judgement of commanders that determines victory or defeat.

Major General Mustafa Tlas, was the Syrian Minister of Defence and overall field commander during the October War. His decision to establish his field headquarters midway between Damascus and the frontlines so as to fulfil both his military and political functions was a major blunder. At critical stages of the battle, he ordered his field commanders to break off their operational duties to return to his headquarters, wasting valuable time when resolute decisions were required. Arguably this lack of flexibility in the command structure was to deny the Syrians victory in the October War.

Early in 1973, General Ahmed Ismail, the Egyptian War Minister, began to hammer out a common strategy with his opposite number in Syria, Major General Mustafa Tlas. Tlas was one of the many politically conscious officers in the Syrian Army and had visited Moscow, Peking and Hanoi. He had written books on guerrilla warfare and the campaigns of the prophet Mohammed. He had also been appointed as the overall field force commander on the Golan. Establishing his headquarters halfway between Damascus and the front line in an attempt to co-ordinate the separate functions of political control and command in the field, Tlas fatally fell between two stools. Because he felt unable to leave his headquarters to visit his subordinate commanders and take personal stock of the situation, he was obliged to recall them at critical moments when they should have been controlling the tactical battle. It was to have a profound effect on the outcome of the war.

The Syrian Chief of Staff was Major General Youssef Chakkour, an Alawite; the director of operations was Major General Abdul Razzaq Dardary, whose deputy was Brigadier Abdullah Habeisi, a Christian more concerned with military strategy and tactics than political manoeuvring. To many officers in the higher echelons of the Syrian armed forces, a military career was simply a means of political advancement rather than the profession of arms in the defence of the state. There were of course some notable exceptions.

Brigadier General Omar Abrash, general officer commanding the Syrian 7th Infantry Division, was a graduate of the US Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth. General Abrash led his division from the front and was directing operations at the anti-tank ditch as his forces opened the attack towards Kuneitra. In his path were the Centurions of the 77th Battalion of the 7th Armoured Brigade. Repeatedly, Abrash hurled his tanks at the Israeli positions with desperate gallantry. By the late afternoon of 8 October, the 7th Armoured Brigade was on the verge of collapse. At dusk on that fateful Monday evening, Abrash rallied his remaining tanks for one last attack relying on the Syrians’ superiority in night-fighting equipment to overwhelm the Israelis. At that critical juncture, Abrash’s tank was hit by an APDS round and burst into flames, killing the courageous commander. The attack was fatally postponed until morning, granting the 77th Battalion some vital respite and time for reinforcement. Lacking Abrash’s dynamic leadership, the attack was contained after fierce fighting and the Syrian onslaught faltered, never to recover.

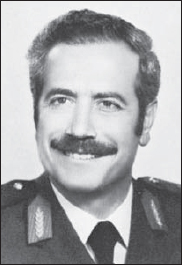

The Israeli Defence Minister, General Moshe Dayan visits troops on the Golan Heights in company with Major General Yitzhak ‘Haka’ Hofi, the commander of the Northern Front during the October War. Dayan’s deeply pessimistic assessment of the fighting on the Golan Heights during the first days of the war led to much despondence in the Israeli cabinet and GHQ but it did lead to the total commitment of the IAF and reinforcements to the Northern Front at the expense of Southern Command in the Sinai.

In 1973 the Chief of Staff of the IDF was Lieutenant General David ‘Dado’ Elazar. Born in Sarajevo in 1925, he distinguished himself as a member of the Palmach during the War of Independence in 1948. He was an infantry brigade commander in the 1956 Sinai campaign, after which he became the commander of the Israeli Armoured Corps from 1957 to 1961. Thereafter he always wore the tankers’ black beret and he did much to foster the predominance of the tank within the Israeli Army. In 1962 he was promoted to Major General and four years later took over Northern Command, where he was responsible for the brilliant campaign to capture the Golan Heights during the Six Day War. On 1 January 1972 he became the Chief of Staff of the IDF.

By a quirk of fate, the majority of the top posts within the Israeli Army changed during the months leading up to the October War so the new incumbents were relatively inexperienced; for instance, the GOC of Central Command took up his appointment just six days before the war began. Hours before the outbreak of the October War, the Israeli cabinet ordered the partial mobilisation of the reserves but Elazar on his own authority organised a general mobilisation – it was a critical decision that did much to save the state of Israel. After the war, however, the Agranat Commission found him negligent in failing to read Arab intentions. He resigned as Chief of Staff on 2 April 1974 and the Labour government of 30 years fell soon afterwards. He died while playing tennis in 1977.

Brigadier General Rafael ‘Raful’ Eitan was the commander of the inadequate forces tasked with defending the Golan Heights from Syrian attack. A tenacious character he refused to countenance retreat and handled his ever-diminishing units with adroit skill against overwhelming odds until sufficient reserves arrived on the Golan Heights to rescue the desperate situation.

Major General Yitzhak Hofi was appointed general officer commanding Northern Command in 1972. Like so many officers in the IDF, he had acquired a nickname and was known as ‘Haka’. A quietly spoken, dour man of few words, Hofi exuded an air of firm authority born of many years’ experience of border fighting as a paratroop commander. During the autumn and winter of 1972/73, his command fought several bitter ‘battle days’ when the Syrians crossed the ceasefire line and clashed with Israeli forces. In the second of these ‘battle days’, the Syrians used Sagger ATGW missiles for the first time in large numbers, destroying several Israeli tanks. Hofi immediately issued his frontline troops with more mortars to counter the Sagger and on the next ‘battle day’ they proved so effective that the menace was largely neutralised and very few hits were sustained. Hofi also launched a comprehensive overhaul of the military infrastructure of Northern Command, during which hundreds of kilometres of unpaved tracks were created, to speed the deployment of artillery and tanks across the Golan. At intervals along the tracks, tank ammunition (200 rounds per tank on the Golan as of 6 October 1973) was dumped to ease replenishment. The armoured mobilisation centres were also moved closer to the frontline near the Sea of Galilee including Rosh Pina, the Headquarters of Northern Command. Rigorous exercises confirmed that these measures cut mobilisation times by up to half – this would prove crucial after 6 October. Simultaneously, the anti-tank ditch in front of the Purple Line was extended and deepened to slow any Syrian attempt at an armoured breakthrough and channel their tanks into prepared killing grounds. Only days before the war, further minefields were laid along the Purple Line. Hofi’s preparations in the months before the war were to play a vital part in the success of Israeli arms. Like his counterpart at Southern Command, Major General Shmuel Gonen, Hofi was to suffer intense pressure in the opening days of the war but, unlike Gonen, ‘Haka’s’ reputation survived the October War intact. Major General Yitzhak Hofi subsequently became the head of Mossad, Israel’s Secret Service.

The forces stationed on the Golan were commanded by Brigadier General Rafael ‘Raful’ Eitan. Another taciturn man of stocky build and dark complexion, Eitan was first and foremost a farmer and happiest when tending his animals. After leaving the army in the early 1950s, he returned to farming. During the war of 1956, however, a friend reproached him, saying: ‘They are killing Jews and you are milking cows.’ Eitan rejoined the army as a paratrooper and gained a reputation as a ferocious fighter. He was considered by many colleagues to be a safe pair of hands but of no great intellect. Eitan was shot in the head during the 1967 war; when he was subsequently promoted many thought it proved that you did not need brains for advancement in the IDF. He subsequently led the reprisal raid that destroyed 13 Arab airliners at Beirut Airport on 28 December 1968. After blowing up the planes, he calmly strolled into the transit lounge bar and ordered drinks for his men. As commander of the 36th Armoured Division or Ugda Raful, Eitan was temperamentally suited to the desperate defensive battle fought on the Golan – courageous with keen tactical skill and a refusal to countenance retreat. He remained at his underground bunker headquarters at Nafekh until Syrian tanks were literally at his door. His fellow commanders on the Golan were equally impressive.

As the commander of Ugda Musa, the 146th Reserve Armoured Division, Brigadier General Moshe ‘Musa’ Peled issues orders from his M3 halftrack command vehicle during the counter-attack on the Golan Heights. After the October War, he became the commander of the Israeli Armoured Corps.

Brigadier General Dan Laner was an experienced officer whose war record stretched back to World War II. During the Six Day War of 1967, he led the attack that captured the Golan Heights. In February 1973 he was released from active service but in May, fearing the outbreak of war, General Elazar directed him to form and activate a new reserve division as soon as possible. On 6 October he rushed to the Golan Heights and quickly realised the gravity of the situation. Rather than waiting to mobilise his entire formation as instructed, Laner stood on the Benot Ya’akov Bridge acting as a military policeman and directing platoons and companies of tanks up the escarpment as soon as they were formed. It was to prove a vital measure in stemming the Syrian onslaught. That night, Laner suggested to Hofi that he take over responsibility for the southern half of the Golan while Eitan directed operations in the north. Hofi was quick to agree. It was this flexibility in command and control by the field commanders and the stubborn resistance of their men that allowed the Israelis to contain the Syrian onslaught. Laner’s Ugda subsequently led the major thrust of the Israeli counter-attack back to the Purple Line and into Syria. His appreciation of Iraqi 3rd Armoured Division’s intentions and the trap he laid to destroy their offensive were masterly. Brigadier General Dan Laner is generally recognised as being the ‘man of the match’ in the war on the northern front. After the war, he returned to a well-earned retirement.

An equally formidable leader was Brigadier General Moshe ‘Musa’ Peled. Another farmer by birth, Peled was an outspoken, hard-bitten armour officer who was GOC of the 146th Reserve Armoured Division (Ugda Musa) following his appointment as the commandant of the Command and General Staff School of the IDF. Unlike many in the IDF high command, Peled was convinced that war would break out in 1973 and he trained his troops accordingly. Although due to take up a new appointment from 3 October, Peled immediately rejoined his division on Yom Kippur. As he drove to the depot at Ramle, his car was stoned by orthodox Jewish children for travelling on the holiest day of the year. The mobilisation of Ugda Musa went to plan but much of its equipment was outdated including old Sherman and petrol-engined Centurion tanks. As a division of the strategic reserve, Ugda Musa was originally slated for service in Sinai, but on the second day of the war General Elazar ordered the division to the Golan Heights. Many of its tanks broke down en route for want of tank transporters. Once again a field commander took a decisive executive decision. Peled decided to commit his division along the road south of the Sea of Galilee towards El Al and up the Gamla Rise rather than, as his orders specified, over the Arik Bridge, which was the main line of communication for Ugda Laner. His prompt action did much to contain a dangerous Syrian thrust towards the heart of Israel. After heavy fighting in the southern Golan, Peled’s division relieved Ugda Laner in the closing days of the war and was then transferred to the Southern Front in Sinai. After the October War, Brigadier General ‘Musa’ Peled became the commander of the Israeli Armoured Corps from 1974 to 1979 and did a fine job rebuilding the Heyl Shirion into a modern combined arms force equipped with the indigenously produced Merkava MBT, which incorporated many lessons from the high-intensity combat of the 1973 war.