Water resource management has been conducted in a fragmented and unintegrated manner in many parts of the world. The fragmented approach may be caused by the nature of different specialised disciplines in relation to the study of water, and many specialised departments have been created at the national level to deal with the water sector. The situation becomes more complicated in a federal system where legislative powers are distributed between different levels of government and specialised departments exist at these different levels. In Malaysia, legislative powers over water-related subjects can be found in all three legislative lists; the Federal List, the State List and the Concurrent List. This chapter will analyse the historical development of the constitutional division of water jurisdiction and analyse the water conflict between the Federal Government and the State Government of Selangor. It will also determine whether water jurisdictions have been distributed according to the subsidiarity principle; i.e. according to the most effective level to make decision on a particular matter.”

Since the birth of the country, water has always been regarded as a ‘state subject’. This was emphasised by the Reid Commission which stated:

At present, control of inland waters, including all rivers and streams, water supplies and storage is exercised by the States and subject to rights of navigation and to special provisions where the interests of two or more States or the interests of the Municipality of Kuala Lumpur are concerned, we recommend that they should be State subjects.1

The Commission acknowledged the inherent relationship between land and water when it decided which government can control water matters. Interestingly, in the Malay vocabulary, the word tanah (land) and air (water) are combined together as tanah air which means ‘homeland’. This demonstrates the close connection between land and water and shows that it is difficult to treat them as two different subjects. The Commission noted that water resources protection was intrinsically linked with land; hence fell under the States’ control. It stated:

Water power has been little developed and there has not been sufficient control of erosion and silting. We regard these as important matters. We recommend that water power should be a Federal subject but soil conservation, owing to its close connection with the use of land should be a State subject.2

The Commission also recommended that there should be concurrent powers for drainage and irrigation. This was because the state governments lacked technical and financial capacity to carry our large water projects for agriculture. The same applied to the rehabilitation of land which had suffered soil erosion, as the Commission believed that it would be dealt with effectively through national development and conservation of natural resources.3 Following these recommendations, jurisdiction over water-related matters has been distributed as follows:

Federal List |

State List |

Concurrent List |

8. Development of mineral resources, mines & mining 9. Shipping, navigation & fisheries 10. Transport 11. Federal work & water |

4. Local government 6. State works and water (Subject to the Federal List, water (including water supplies, rivers and canals); control of silt; riparian rights) 12. Turtles and riverine fishing |

5. Town and country planning 7. Public health, sanitation & prevention of disease 8. Drainage and irrigation 9. Rehabilitation of mining lands |

Table 1: Legislative Lists on Water under the Federal Constitution

It is observed from the Table that federal government involvement in water relates to the infrastructural aspect of water matters, while the ownership and custodianship of the body of water itself remains with the State, except of course when the State sells water to another State. By virtue of Article 73, the laws passed by Parliament can be applied to the whole or any part of the Federation, while state laws can be applied to the whole or any part of the state. Article 74 of the Federal Constitution further emphasises that Parliament can only make laws on matters under the Federal List and the Concurrent List. Thus, the federal government can legislate on ‘water supplies, rivers and canals [only if it is not within] one State or regulated by an agreement between all the states concerned; production, distribution and supply of water power’. Abdul Kader notes that this provision confines the federal power to water which ‘flows through the boundaries of two States or more’ or in a shared river basin; and intervention is allowed when state governments meet deadlock in their negotiations.4

The Federal Government’s right to legislate on water-related matters may extend to water matters under the State List by virtue of Article 76 of the Federal Constitution. This legislative exercise is limited to three conditions; (1) for the purpose of implementing any treaty, agreement or convention between the Federation and any other country; (2) for the purpose of promoting uniformity of the laws of two or more States; or (3) if so requested by the Legislative Assembly of any State.5 However, such laws must be adopted as state laws and can be amended by subsequent state laws.6 The National Forestry Act 1984 is seen as the best illustration on uniformity. The law was passed to provide a uniform administration, management and conservation of forests as an important water catchment. The State Legislative Assemblies adopted the law through a state forestry enactment, as can be seen in the Forest Enactment Kedah No. 15/1357 and the Forest Enactment Kelantan No 4/1939.

On the other hand, the federal government may extend the legislative power of states to legislate on water matters under the Federal List. This can be done under Article 76A (1) and is subject to any condition or restriction Parliament may impose. The creation of such law will not conflict with Article 75 of the Federal Constitution and will be treated as the exercise of state power to legislate on Concurrent matters so as to comply with the provisions of Articles 79, 80 and 82 of the Federal Constitution.7 In addition, the State legislature has the power under Article 77 to make laws on any matters not listed under any legislative lists. In addition, a state has the right under Article 78 to refuse the application of any law which restricts its right or its residents’ rights of navigation on or irrigation from any river wholly within that state. Thus, unless the river flows into another state8, the state government has the liberty to develop the river according to its wishes. By virtue of Article 79, the state government must be consulted when laws are passed on concurrent matters.

Apart from the distribution of legislative powers relevant to water, the Federal Constitution also lists the distribution of executive powers which can affect water-resources management. Article 80 (2) provides that the executive authority of the Federation may extend to the state’s jurisdiction on several occasions. In this respect, Article 93 permits the federal government to conduct surveys and publish statistics regarding water resources with the assistance of the state government. Article 94 provides authority to include ‘the conduct of research, the provision and maintenance of experimental and demonstration stations, the giving of advice and technical assistance to the Government of any State’ in matters under the State List. This has been extensively used in the irrigation sector as the State Departments of Irrigation and Drainage always seek assistance from their counterparts at the federal level as they lack financial and technical capacity in dealing with water projects.9

It is also noted that Article 92 deals with development plans like the five-year Malaysia Plan, which incorporates planning for future water projects for the country. A development plan is defined as any plan ‘for the development, improvement, or conservation of the natural resources of a development area, the exploitation of such resources, or the increase of means of employment in the area’.10 This means that a federal agency may come out with a plan that lays down mechanisms for developing, improving, conserving or even exploiting the water resources of a development area, although the management of the water body itself lies with the State. Thus, there are several mechanisms which are available to be used by the federal government in dealing with water on the basis of national importance and development.

State jurisdiction over water resources has been exercised even prior to the drafting of the Federal Constitution with the enactment of the Waters Ordinance 1920.11 It was passed under British rule and applies to the former Federated Malay States i.e. Pahang, Perak, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan; the former Straits Settlements i.e. Malacca and Penang; and the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur.12 According to section 3 the entire property in and control of all rivers in any State is and shall be vested solely in the Ruler of such State. Thus, the state government has the liberty to decide who gets the water, how much water can be abstracted, and when it can be released. In 1955, the Water Supply Enactment was passed to empower the State Water Supply Authority to supply water. Similar provisions of the Ordinance and Enactment exist in the state enactments of the former Non-Federated Malay States of Johore, Kelantan, Terengganu, Kedah and Perlis.

Since independence, agriculture has been the major economic contributor in Malaysia, and so a number of laws have been passed pertaining to water resources, irrigation and drainage. In 1953, the Federal Government passed the Irrigation Areas Act to regulate irrigation for agricultural development followed by the Drainage Works Act 1954 for drainage regulations. In 1972, the Federal Government passed two statutes to stimulate paddy plantation, as rice is the country’s main staple food, and to improve the irrigation system for the paddy farms in the states of Kedah and Kelantan. They are the Muda Agricultural Development Authority Act of Kedah and the Kemubu Agricultural Development Authority Act of Kelantan.

In 1991, ‘Vision 2020’ was promulgated to set the country’s goal to become a developed nation by the year 2020. The economic growth of Malaysia continues with rapid industrialisation; but it has also brought various forms of environmental degradation, especially to its water resources. This is because the development took place with a view to profit and failed to take into account the health of surrounding ecosystems. Large-scale land clearance, together with illegal logging activities, has led to soil erosion causing high sediment loads in adjacent rivers. These rivers were further polluted by effluents from the rubber and oil palm mills, and together they account for nearly 90 per cent out of the total industrial pollution load of local rivers.13 The increase in population caused a rise in overall demand for clean, potable and non-potable water. However many rivers have been contaminated by untreated domestic wastewater, sewage and hazardous wastes from industries.14

To date, the duty to control water pollution is spelled out in a dozen pieces of legislation and this lead to gaps and overlaps in responsibilities. The Environmental Quality Act 1974 and its regulations can be regarded as the main pieces of legislation in this area. The laws are enforced by the Department of Environment under the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. However, the laws are only applicable to point-source pollution such as agro-based and industrial discharges, livestock farming and sewages. It is the local government that has jurisdiction, under the Local Government Act 1976, to control non-point source pollution. The local government also has the power to maintain and keep in repair all surface and storm-water drains, culverts, gutters and watercourses under section 54 of the Street, Drainage and Building Act 1974. However, the demarcation of pollution makes it difficult for the general public to determine which department to refer to in the event of pollution.

Water pollution also originates from land-based activities and several pollution-control duties are spelled out in the Land Conservation Act (LCA) 1960, the Town and Country Planning Act (TCPA) 1976 and the National Forestry Act (NFA) 1984. The LCA concerns the conservation of hill land and the protection of soil from erosion and siltation. Section 3 of the LCA provides the Ruler of a state with power to declare any area of land in the state as hill land, and no person is allowed to undertake activities on hill land that may cause soil erosion. In addition, section 14 of the LCA allows the Land Administrator to make orders to prohibit owners of land from removing any trees; to require them to make dams or retaining walls on the land of drains and watercourses; or to do any act that would prevent the passage of earth from the land to another land, river, canal or drain. The power to make a tree preservation order is also provided to the local government under Part VA of the TCPA. With respect to forest and its importance towards water sustainability, the NFA empowers the State Director of Forestry to classify amongst others; soil-protection forest, soil-reclamation forest, flood-control forest; and water-catchment forest.15 Thus, various statutory provisions have been legislated to protect water from pollution caused by soil erosion and siltation.

It can be seen that the bulk of water-related laws focuses on water-pollution control and prevention. The question remains whether these laws have been effectively enforced, as the number of polluted rivers in the country stood at an average of 6 per cent from 2005 to 2009, while the slightly polluted rivers amounted to 55 per cent within the same period. Although the number of polluted rivers reduced from 10 per cent in 2005 to 6 per cent in 2009, the number of slightly polluted rivers increased from 35 per cent to 45 per cent.16 These findings seem ironic as various pieces of legislation have been passed to deal with pollution control. For a developing country like Malaysia, pollution will not only affect the continuous supply of clean water for the general public, it will also affect other water-users such as the manufacturing sector as well as services industries like the hotel and tourism sector.17 It is thus not surprising that the tenth Malaysia Plan (2011–2015) paid extra attention to pollution problems and laid down several measures to improve pollution control which include strengthening the EQA and revising the Water Quality Index.18 The Plan also lays down a long-term strategy for the National Water Services Industry Restructuring Initiatives (NWSIRI) as elaborated below.

The history of water supply in Malaysia dates back to the 1800s. As the first British settlement, Penang witnessed the construction of the first untreated water supply system through an aqueduct in 1804 and the first cast-iron main in the country in 1877.19 This was followed by Sarawak and Kuala Lumpur in 1887 and then Malacca in 1889.20 The rapid increase of population in Kuala Lumpur after independence raised the overall water demand and caused water shortage and rationing. As a result, the Klang Gate Dam and the Bukit Nanas Treatment Plant were constructed in 1959 to meet the increasing demand.21 By 1999, the number of dams in Malaysia stood at sixty-nine, and from this thirty-five were developed for water supply, sixteen for multi-purpose and eighteen for irrigation and hydropower.22

Until 2005, the Federal Constitution allowed the state governments to legislate on water supplies; rivers and canals; and control of silt and riparian rights, as an aspect of the Rulers’ proprietary rights under the Waters Act. Nonetheless, water-supply operation is expensive and takes the bulk of states’ budget. As a result, the State of Terengganu corporatised its water supply operation in 1995, followed by Kelantan, Johor and Selangor. To date, only the smallest state of Perlis, together with the Federal Territory of Labuan, have not ventured into privatisation of the water supply, which remains operated by their respective Water Supply Department. Even with privatisation, the water operators are still suffering from the rising cost of infrastructure, and this is not helped by the present low water tariff. In addition, the privatisation package varies from one state to another and has led to a variation of performance level amongst the states.23

The Federal Government has allocated a massive budget for the water-supply sector24 but the power to regulate the water operators remains with the state government. This made it difficult for the Federal Government to improve the overall water-supply standard. Around 2000, a series of events occurred that strengthened the belief that the federal government must regulate the water-supply sector. These included the prolonged drought in 1998, the report of the National Water Resources Study, which showed that there was a need for more interstate water transfer to meet the increasing demand, and some indications to prove that private companies were running the water supply sector at a loss.25 As a result, the Federal Government embarked on the National Water Services Industry Restructuring Initiatives (NWSIRI) to reform the water supply sector. The Federal Government would lead the transformation programme and enhance the Public-Private-Partnership (PPP) in the water sector.

NWSIRI required a greater federal government role in financing as well as regulating the water supply sector. To this end, a constitutional amendment was made in 2005 to remove ‘water supply’ from the State List to the Concurrent List. In 2006, the Federal Government passed two important statutes, the Water Services Industry Act (WSIA) 2006 and the Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Air Negara (SPAN) Act 2006, to mark the new era of federal government involvement in the water services sector. The SPAN Act was enforced on 1 February 2007 and paved the way for the formation of SPAN or the National Water Services Commission. SPAN would become the country’s regulator on matters pertaining to water supply and services through the laws and regulations under WSIA. The WSIA came into force on 1 January 2008 and repeals the Sewerage Services Act (SSA) 1993 and relevant state water supply enactments in Peninsular Malaysia.26

With the new legislative power under the Concurrent List, the Federal Government established SPAN to regulate the water operators through WSIA with the hope that they would become more efficient and ensure a sustainable supply of water. SPAN would operate under the purview of a new Ministry of Energy, Water and Communication.27 State governments are now left with jurisdiction over ‘rivers and canals (but excluding water supplies and services), control of silt and riparian rights and subject to the Federal List, and if the water source is wholly within the state’s territory’.28 Khalid et al argue that the amendment has to some extent de-federalised the water sector in Malaysia and can be successfully implemented only with the support of the state governments.29 To date, full migration to the new SPAN regime has not been properly secured, not only from the state government under the opposition coalition, but also from those with political allegiance to the federal government. This may be due to the fact that state governments have been very cautious of their rights over water and wanted to ensure that they will benefit by migrating to the new SPAN regime.

The constitutional amendment confirms that state government retains its control over water sources. The federal government’s new role is only limited to regulating the water companies through the WSIA, which should improve the sector in the long run. A closer analysis of the WSIA however shows otherwise. There are several provisions which deal with ‘watercourses’ that include rivers, streams and creeks.30 Section 121 (2) (a) for instance provides that any person who contaminates any watercourse or the water supply system with the intention to cause death and ‘where death is the result of the act, shall be punished with death or imprisonment for a term which may extend to twenty years’. In addition, section 121 (3) provides that it will not be a defence for the offender to argue that the licensee who owns the water supply system did not take action to stop the supply of water as soon as he becomes aware of the contamination. The WSIA also provides for the establishment of the ‘Water Industry Fund’, which will be used for the protection of the watercourses and water-catchment areas, to ensure sustainability of water supply and for the improvement of water quality in the watercourses.31

It can be argued that these provisions deal specifically with the water source itself and are redundant with several provisions in the Selangor Water Management Authority (SWMA) Enactment 1999 to protect and develop water sources, as well as to ensure resource use efficiency and conservation.32 In addition, Section 121 of the WSIA conflicts with the authority’s powers of enforcement under Part XII of the 1999 Enactment. It is submitted that the Commission should only be concerned with the infrastructural aspect of water and not the water aspect of the water-supply systems. It can also be submitted that these WSIA provisions are ultra vires for encroaching into state jurisdiction under the Federal Constitution. Before further analysis can be made on the workability of such provisions, it is important to understand the reasons for conflict between the federal and state government of Selangor in the water sector following the constitutional amendment. Selangor is chosen as the case study as it has enacted a specific law on water resources management and it has been governed by the opposition coalition since 2008. Selangor water is also pertinent for the national economy since it is the richest state in the country and both the federal territories of Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya are dependent on Selangor, of which they were part before becoming Federal Territories, for their water supply.

Selangor has the highest gross domestic product (GDP) in Malaysia, contributing an average of 21 per cent of the national GDP from 2005 to 2010. Most of the income is derived from the manufacturing and service sector, with a percentage of 35 per cent and 55 per cent respectively in 2010.33 The Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, which was previously part of Selangor contributed an outstanding GDP of an average 13 per cent from 2005 to 2010 and most of it comes from the financial-services sector.34 The average GDP from Selangor and Kuala Lumpur together amounts to 34 per cent of the country’s GDP and investment will continue to grow with the correct infrastructure in place. Occasional water disruptions have hindered proposed investments, and over 700 development projects were reported to have been delayed by the 2014 water crisis.35

Following the rise of Pakatan Rakyat in the twelfth and thirteenth general elections, SPAN’s aim to regulate all concessionaires can be challenging, as illustrated in the current dispute between the Federal government, led by Barisan Nasional, and the Selangor Government now led by Pakatan Rakyat.36 Pakatan Rakyat has affirmed their stronghold in Selangor after a comfortable win of thirty out of forty state seats in the thirteenth General Election. Nevertheless, the new Selangor state government has a challenge to manage its water sector when four private concessionaires are handling its water supply and services. Instead of one water treatment operator and distributor like in other states in Malaysia, there are four private concessionaires in Selangor, which are Puncak Niaga Sdn Bhd (PNSB), Syarikat Pengeluar Air Sungai Selangor Sdn. Bhd. (SPLASH) and Konsortium Abass Sdn Bhd. (ABASS) as the water treatment operator; and Syarikat Bekalan Air Selangor Sdn. Bhd. (SYABAS) as the sole water distributor in Selangor and the Federal Territories of Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya for thirty years beginning 1 January 2005.37

The new state government believes that this arrangement is inefficient and has caused poor services in contrast to the companies’ high profits. As they continue to hold over 70 per cent interests in all water assets in Selangor, the state government announced that they would buy all water assets and control water distribution rights. Upon acquiring the remaining shares, it would migrate to the SPAN regime and transfer the assets to the Federal Government at a price that would cover the cost of acquisition and compensation for the early termination of concessionaires’ contracts. Several bids were made that started in February 2009 that amounted to RM5.709 billion which was based on one-time net book value proposed by the Water Asset Management Company. This was rejected by PNSB, SYABAS and SPLASH. In June 2009, the bid was increased to RM9.218 billion but was rejected by PNSB and SYABAS. Another bid was made in January 2010 for RM9.277 billion but was rejected by all concessionaires. The final bid of RM9.65 billion was made in 2013 but was rejected by all except ABBAS.38

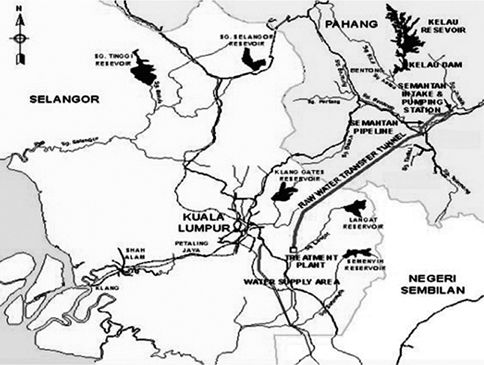

Before the above problem can be properly solved, there is another on-going conflict about the data provided by both governments as to future projection of water shortages. According to the National Water Resources Study (2000 to 2050), there will be a serious water shortage in Selangor and the Federal Territories of Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya in 2014. This prompted the Federal Government to initiate an interstate water transfer from the state of Pahang to Selangor.39 The new state government, however, thinks otherwise and claims that shortages may occur if SYABAS fails to keep clean water reserves at a good level; and believes that water catchments in Selangor can cater to all users until 2019.40 The state government also claims that water disruption will not arise if SYABAS can reduce its high non-revenue water rate. Despite the state government’s disapproval, the Federal Government decided to continue with the controversial Pahang-Selangor Inter-State Raw Water Transfer project on the basis of its national importance.41 The project will bring 1.89 billion litres of water daily to meet the ever-increasing demand from water users in the Klang Valley. It involves the development of a regulating dam in Kelau Pahang, a pump station at Sungai Semantan in Temerloh, an 11.8km twin pipeline, and a 44.6 km water tunnel that will carry raw water into the proposed Langat 2 water-treatment plant.42

Table 2: Map of Interstate Water Transfer Project from Pahang to Selangor

It can be seen that there are two segments of the Selangor water conflict: the delay in the Langat 2 project and the disagreement over the value of the takeover bid of the concessionaires, which ended on 31 December 2013. On 8 January 2014 the Selangor Government accepted the Federal Government’s decision to invoke section 114 of the WSIA which permits the minister to direct SPAN to assume control of the water supply and services of the concessionaires on the basis of national interest.43 Through this the Selangor government will gain control over the water-supply sector and two state representatives will assist SPAN in carrying on the whole of the licensee’s business and affairs.44 A Memorandum of Understanding was inked between the Federal and State Governments on 26 February 2014 to conclude the offer of RM9.65 billion made by the Selangor Government. In return, the State Government will approve the development of the Langat 2 Water Treatment Plant in Langat Selangor to complete the interstate water transfer project from Pahang to Selangor.45

It took almost six years for the two governments to come to some sort of initial agreement in the Selangor water dispute. The Federal Government, through the Ministry of Energy, Water and Green Technology, had to invoke section 114 of WSIA on the basis of national interest. Selangor is the major contributor of national income, and water disruption in Selangor can delay the economic and financial process and hence become a national concern. Prior to the 2005 constitutional amendment the state government had all control over water resources and services, and if it believed that its water reserve was enough to cater for the needs of the citizens, that should be the case. Since the Federal Government took control of water supply and services through SPAN, water matters have become so centralised that it is difficult for the state government to interfere, even though it is concerned with the welfare of its citizens. This scenario arises from strict application of dual federalism in Malaysia and it provides fewer manoeuvres for cooperation in the water sector. As water knows no boundary, it is vital that steps are taken to redefine the relationships between levels of government for a more sustainable management of water resources

It is observed that the water sector in Malaysia remains challenging and controversial after fifty years of Malaysian federalism. What is needed now is to redefine the role of different levels of government in water resources management in order to ensure a more holistic management of water resources. Towards this end, the principle of subsidiarity can be employed as it allocates decision-making power based on certain criteria to ensure that a decision is made at the most appropriate political or administrative level.46 The principles are seen as synonymous with the concept of federalism as both aim towards appropriate power-sharing between different levels of government.47 The basic idea of subsidiarity, that federal government should not intervene unless necessary, is normally provided under a federal constitution.48 Nevertheless, it is pertinent that subsidiarity is used to ensure that the federal government decide only on matters of national importance but not in relation to a localised problem. Subsidiarity will restore the ability of the states to respond to issues of local concern and preserve the ability of the federal government to address issues of national concern.49

A multilevel or polycentric government like a federal system provides an opportunity for subsidiarity principle as it allows something to be done at lower levels while reserving a certain capacity to a higher level for collective action. However, this may be easier said than done in Malaysia since the Federal Government possesses greater legislative and financial power than the state and local governments. The decision to give greater power to the federal government was made even during the promulgation of the Merdeka Constitution as a mechanism to ensure uniformity, efficiency and solidarity between member states in the federation. Thus direct application of subsidiarity within Malaysian federalism may not result in effective decision-making at lower level as the local governments lack financial, technical, political and legislative capacity.

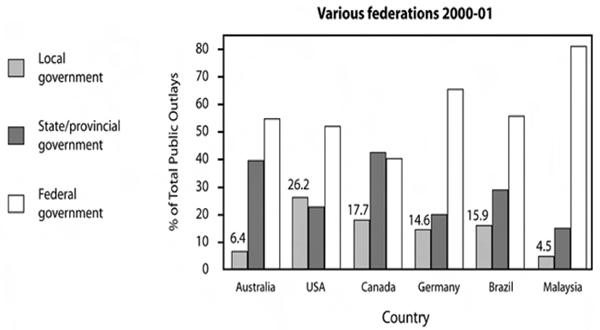

Subsidiarity aims to protect the independence and legislative authority of the local government in dealing with local river basins. Within the water sector in Australia, the local governments are identified as the closest and most effective level to manage and make decisions on a river basins. Nonetheless, subsidiarity also requires that the local authorities are legally, technically and financially capable to make correct decisions for the rivers. It is interesting to note that a study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF)50 shows local authorities in Australia and Malaysia as having the lowest total public expenditure compared to other federal systems in the world as shown below.

Table 3: Total public outlays (2000–2001)

According to this assessment, the average local government in Malaysia has the lowest fiscal capacity (4.5 per cent) compared to other federal systems in the world like Brazil (15.9 per cent) and the USA (26.2 per cent). The local government in Australia is slightly better off than its counterpart in Malaysia with 6.4 per cent of total public outlays, but financial assistance can be gathered from the state governments which possess nearly 40 per cent of the total share. As a result, their financial positions remain far better than Malaysia’s because state governments in Malaysia have an average of less than 20 per cent. This affirms Malaysia’s position as the most centralised in fiscal federalism with 80 per cent of total outlay resting with the federal government. This also indicates that local government in Malaysia are financially dependent on the state or federal government to run costly programmes in their river basins. In the light of extreme weather brought about by climate change, they may also be left without enough funding, since the federal and state governments are more concerned with flood mitigation program.

Today, most of the water resources management in Malaysia is carried out by the Department of Irrigation and Drainage, both at the federal and state level. River engineering has been the main task of the Department since the early 1990s, and it has implemented various programmes through the Integrated River Basin Management (IRBM) approach such as the ‘1 State 1 River’ and the ‘JPS@komuniti’ programmes. Following a restructuring process in the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment in 2009, a revision was made to the Ministerial Function Act 1969 (Act 2) and the Ministers of the Federal Government Order 2009 (P.U. (A) 222) to the effect that the department is now equipped with powers over water resources management. These include planning and management of river basins, and flood-mitigation programmes, as well as water management for crops and other agricultural needs. Although the department has the technical capacity to implement structural and non-structural measures that will improve the water sector, the new powers may conflict with state’s jurisdiction over water resources management. This is especially relevant in Selangor and Kedah which have established their respective water resources authority. Although an enormous duty has been given to the department, uncertainties remain with the delineation of powers between the department and the state authority in regulating states’ water resources.

It is observed that the initial division of power in the Federal Constitution has been properly reasoned and argued to allocate the right level of government with the appropriate decision-making capacity in water resources management. Nevertheless, recent developments in the sector show that the Federal Government has gained greater control in the sector through the constitutional amendment, and has taken the lead in legislating matters under the Concurrent List, namely the water supply and services as well as drainage and irrigation. Despite the fact that the Department operates both at the federal and state levels, it is the local government which is the closest to the local water problem and should be able to make decisions on that matter. It is noted that the local government will refer to the Department for technical advice on a proposed development plan. That advice may only be taken up as conditions in planning permission and the local government may not be able to continuously supervise the developers’ compliance of such conditions.

The question remains whether the Department of Irrigation and Drainage is the most appropriate decision-maker for the river basins. It is noted that the new power for the Department relating to water resources was passed after the State of Selangor established the Selangor Water Management Authority. The only difference between the two is that the Department is heavily involved with river engineering whilst the state authority is more concerned with water sustainability. It is submitted that the Federal Government should not expand the department’s power over water resources as it conflicts with the states’ powers under the Federal Constitution. It is also submitted that the department is not the lowest appropriate level for the river basin. The integration of the overall water resources management must be left with the new state water management authority, while the local government must be equipped with the technical capacity to implement a state’s water decisions.

It is observed from Table 3 that the local authority in Malaysia has the lowest total public outlay and that may affect effective disposal of its duties. The Department, however, has the technical and financial capacity to run water projects. It seems that the Department at the federal level will continue its policy and law-making without acknowledging the fact that the local authority is the most appropriate level to decide on water matters as it is the closest to the water problem. Restructuring of the overall framework will be politically sensitive and time-consuming. In this respect, the local authority must associate itself with the recently established ‘JPS@komuniti’ programme’ to encourage local participation in river basin management and promote collaborative decision-making. As such, the Department’s role in river basin management is to assist, rather than take charge.

From another perspective, the subsidiarity principle has been indirectly applied during the 2005 constitutional amendment when the Federal Government gained more powers in water supply and services. The move towards centralisation in the sector can be seen not only in Malaysia but also in Australia.51 Nevertheless, the Australian examples show that power has been further distributed to the local councils as the most appropriate lowest level of government in river basins management. This is not the case in Malaysia as local government remains almost totally dependent on state and federal governments in managing the river basins. The Selangor water conflict is an example of tensions that will arise in the water sector since it disregards the role that can be played by the lowest level of government in the sector.

After fifty years of Malaysian federalism, water can no longer be regarded as an exclusive ‘state matter’. With the increasing demand for fresh water resources and unpredictable impacts of climate change over water resources, it is presumed that the federal government’s involvement in water resources management will be greater in the future. However, the demarcation between the management of water resources and water supply and services has created conflict between the federal and state government of Selangor. It remains unclear whether the responsibility of ensuring enough water supplies should rest with the federal or the state government. Although the amendment indicates that the federal government will take the lead in water supply and services, it is the state authority’s duty to ensure a continuous supply of raw water from rivers and that requires continuous protection of the surrounding catchment areas like forests. Thus appropriate financial mechanisms must be developed to motivate state governments to conserve their catchment areas.

It is vital to appreciate the fact that sustainable management of water resources within a river basin acknowledges the fact that every person or agency has a role to play in the water sector. Through subsidiarity principles, the most appropriate level of government will be allocated with the appropriate legislative, technical and financial capacity to manage and make decisions on water matters. The 2005 constitutional amendment, however, has further delineated agencies like SPAN, SWMA, the local government, and the Department of Irrigation and Drainage, with overlapping roles and responsibilities in the water sector. An urgent appraisal of power distribution in the water sector is needed to ensure that decision-making is made by the most effective level of government closest to the water problem. If decisions continue to be made at the top, it is feared that water-related problems will remain a never-ending problem. Greater communication and cooperation between all levels of government is thus pertinent to ensure a more holistic and sustainable management of water resources in the country.

_____________

1 Report of the Federation of Malaya Constitutional Commission, 1957, p.46.

2 Ibid.

3 Op.cit., pp.46–47.

4 Sharifah Zubaidah Abdul Kader Al-Junid. ‘Towards Good Water Governance in Malaysia: Establishing an Enabling Legal Environment’, 2004, 3 Malayan Law Journal, p.civ.

5 Article 76 (1) Federal Constitution.

6 Article 76 (3) Federal Constitution.

7 Articles 76 A(2) and (3) Federal Constitution.

8 The Langat River in Selangor flows to the Federal Territory of Putrajaya and the State of Negeri Sembilan.

9 Kheizrul Abdullah, ‘Water for a Sustainable Development towards a Developed Nation by 2020’, Paper presented at the National Conference on Water for a Sustainable Development towards a Developed Nation by 2020 (July 2006).

10 Article 92 (3) Federal Constitution.

11 The law has been revised as the Waters Act 1920 (Revised 1989).

12 The Act ceased to apply in Kuala Lumpur through Section 4(1) of the Water Supply (Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur) Act 1998 and in Selangor through Section 123 Selangor Water Management Authority Enactment 1999.

13 Jeffrey R. Vincent, ‘Reducing Effluent While Raising Affluence: Water Pollution Abatement in Malaysia’, Harvard Institute for International Development, Spring 1993, p.5.

14 ‘River Water Pollution Sources’, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, www.doe.gov.my/webportal/en/info-umum/punca-punca-kepada-pencemaran-air-sungai/

15 Section 10 (1) (b), (c),(d) and (e) of the National Forestry Act 1984.

16 Tenth Malaysia Plan 2011–2015, pp.285-286.

17 The state government of Malacca has spent RM335 million on river rehabilitation programmes since 2002 but not much progress has been made to reduce non-point pollution in the Malacca River. When Malacca was declared as a UNESCO Heritage City in 2008, the Chief Minister appointed a new contractor to solve the problem. The dirty and smelly water from the river deterred tourists from coming to the riverside, see http://empangan-jernih.blogspot.co.uk/2008/05/ali-rustamkecewa-sungai-melaka-masih.html.

18 Tenth Malaysia Plan 2011–2015, pp.285–286.

19 ‘A Glimpse at Water Supply in Malysia: Past and Present’, www.jba.gov.my/images/stories/Semenanjung_Malaysia.pdf

20 Chin Yoong Kheong, The Water Tablet: Malaysia Water Reforms, 2008, Ministry of Energy, Water and Communications, Malaysia, p.17.

21 Ibid, p.19.

22 Ibid, p.23.

23 Op.cit., p.51.

24 In the Sixth Malaysia Plan (1991–1995), RM2.089 billion were allocated for water infrastructure spending and it was nearly doubled to RM4 billion in the Eighth Malaysia Plan (2001–2005).

25 Raja Zaharaton Raja Zainal Abidin, ‘Water Services Agenda in the Ninth Malaysia Plan’, Water Malaysia, Issue 10, 2005.

26 It will not interfere with the operation of subsidiary legislations made under the SSA so long as they are consistent with the WSIA.

28 State Legislative List in the Ninth Schedule of the Federal Constitution.

29 Rasyikah Md Khalid et. al. 2012. ‘Constitutional Issues in Integrating Water Resources Management in Malaysia: A Case Study of the Selangor Water Management Authority’, OIDA International Journal of Sustainable Development, Vol.3, No.8, pp.11–18, 2012.

30 S.2 WSIA.

31 Section 171 (2) (a) (b) and (c) WSIA.

32 Part V and VII of the SWMAE 1999.

33 Review of the National Water Resources (2000–2050) and Formulation of National Water Resources Policy, Volume 14, Selangor, Kuala Lumpur & Putrajaya, Final Report, August 2011, pp.2–16.

34 Ibid, pp.2–11.

35 Soal Jawab TV3, 5 March 2014.

36 Water Talks On, http://thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2009/2/25/business/20090225070358&sec=business, December 26, 2009.

37 www.syabas.com.my/corporate/about-us-corporate-profile

38 Selangor Kini, January 2014.

39 www.kettha.gov.my/sites/default/files/uploads/isu_air/kettha_faq_01.htm.

40 The Star Online, 2011.

41 The Attorney General shall advise on the legality of the project since it will run through Selangor and land is still under the State’s jurisdiction.

43 S. 114 WSIA provides that the Minister may, if he thinks it necessary for national interest, direct the Commission to assume control of part or the whole of the property, business and affairs of a licensee and to carry on the whole of the licensee’s business and affairs or to appoint any person to exercise any of these actions on behalf of the Commission.

44 BERNAMA, Selangor Beri Lampu Hijau Laksana Loji Langat 2, www.bernama.com/bernama/v7/bm/ge/newsgeneral.php?id=1006166

45 New Straits Times, Federal and State Government Sign MoU to Restructure State Water Industry, www.nst.com.my/latest/federal-and-selangor-govt-sign-mou-to-restructure-state-water-industry-1.493565

46 The word subsidiarity originates from the Latin word ‘subsidium’ or ‘to sit behind’ and had been used within the military context during the Roman Empire to describe a group that would sit behind in case extra support is needed. Robert Schutze, “Subsidiarity after Lisbon: Reinforcing the Safeguards of Federalism?”, 68 Cambridge L.J. 525 2009, see also Gregory R. Beabout, “Challenges to Using the Principle of Subsidiarity for Environmental Policy”, 5 U. St. Thomas L.J. 210 2008.

47 Michael Longo, “Subsidiarity and Local Environmental Governance: A comparative and Reform Perspective”, 18 U. Tas. L. Rev. 225 1999.

48 Said Mahmoudi, “Subsidiarity and The Environment: Reflections on the Exercise of Legislative Power by the EC and the Member States”, 6 Finnish Y.B. Int’l L. 505 1995.

49 Jared Bayer, “Re-Balancing State And Federal Power: Toward A Political Principle Of Subsidiarity in the United States”, 53 Am. U. L. Rev. 2004.

50 IMF Government Finance Statistics Yearbook 2002, as quoted in A. J. Brown and J. A. Bellamy (eds), Federalism and Regionalism in Australia: New Approaches, New Institutions?, Sydney, NSW, 2006.

51 The Commonwealth Government of Australia passed the Water Act 2007 to lead the management of the Murray-Darling river basin which was previously governed by various inter-state agreements.