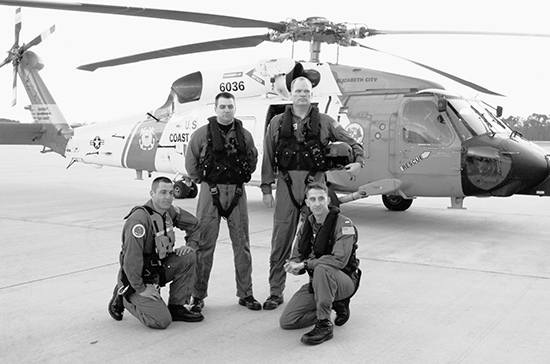

From left to right: Drew Dazzo, Scott Higgins, Nevada Smith, Aaron Nelson

The second Drew hit the water, he started swimming as fast as he could. Now he’s trying to go even faster, afraid that he won’t catch the raft before a wave breaks and buries him in its churning fury. If that happens, he’ll have to start all over again by being ferried to the raft or hoisted back to the helicopter and then repositioned. Foam is coming through his snorkel, so he’s barely taking a breath. He’s got to get to the raft, and is already wondering if he can do this three times.

Rudy and Ben are amazed that the rescue swimmer is in the water and actually gaining on the raft. The tension they feel, being this close to rescue, is unbelievable. Then a wave slides between the raft and the swimmer, blocking their view, and they wonder if he’s still making progress. When the wave rolls by, the swimmer is at the side of the raft.

Drew puts an elbow on the raft, spits out his snorkel, takes two deep breaths, then looks at the men and says, “How y’all doing today?”

Ben is so flabbergasted by what he has just seen and heard that all he can do is smile. Rudy simply says, “You guys are fucking amazing!”

Drew is relieved to hear that comment. When he first looked at Rudy’s eyes, they seemed as wide as garbage can lids, and Drew was afraid the survivor was about to panic. Now he knows the man with the gray beard is not just lucid but has kept his sense of humor. Drew nods and says, “Thank you. Is anyone hurt?”

The rescue swimmer is processing information as quickly as he can, first noting that the raft is in bad shape, that the men do not have survival suits on, and one of the men seems unresponsive.

Ben and Rudy point down at JP. Rudy says, “He is. Broken ribs. He needs to go first.”

“All right, he’s coming with me first.”

Drew sizes up JP. He looks half dead, barely hanging on.

• • •

Scott is pulling the basket bails together so he can insert the hook through their tops. The basket is a metal cage about two and a half feet wide by four feet long, and on each end are floats so that the top of the basket will ride even with the ocean’s surface. Survivors sit with their knees bent and involuntarily hold on to its sides with a viselike grip. Although it is designed to hold six hundred pounds, there is not enough room in it to hoist two people. In some rescues, the strop is used so that the rescue swimmer and the victim can be hoisted together, but that carries more risk for the survivor, who might slip out of the strop. And it is not an option for JP, who is unable to help in the rescue.

Working inside the cabin, Scott is facing away from the doorway. This is the first time he cannot see Drew, and he’s concerned, racing to complete the task. As soon as the basket is on the hook, Scott moves back to the doorway, lies on his stomach, and waits for Drew to let him know when he is ready with the first survivor. He feels like he is watching a science fiction movie play out below. Few people on earth have ever seen waves this big, and it’s almost inconceivable that men are in the middle of it and still alive. He can see Drew’s neon-yellow helmet at the side of the raft, and he knows Drew will be hollering out the procedure for rescue to the survivors.

Come on, come on, frets Scott, hurry up. He’s anxious to start lowering the metal cage, knowing that it might take several attempts to reposition the helo and get the basket close enough for Drew and the first survivor to reach it. Scott also wonders about the first survivor to be taken from the raft. Jeez, I hope he’s cooperative. Drew’s never going to pull this off with a panicked and aggressive victim.

In the cockpit, Aaron can feel the beads of sweat trickling down his chest inside his dry suit. Now that the rescue swimmer is in the water and they are waiting to lower the basket, he has climbed in altitude, to be on the safe side. In calmer weather, he could put the helicopter in the automated “altitude hold” function, but with the seas gyrating below, that’s not an option; the aircraft would be bolting up and down wildly with each passing wave. For Scott to do his job, he needs the Jayhawk as stable as possible, and the best way to do that is in a manual hover.

Aaron cannot see Drew or the life raft, but one thought has been bothering him for the last few minutes: This is taking an awful long time. He’s worried the seas are overpowering the rescue swimmer and the wind will be too much for the hoist operator to perform a safe extraction of survivors. He’s also reconsidering his earlier thought that they would have plenty of fuel so they could take their time with the rescues. With everything moving much slower than normal, Aaron is concerned that they’ll bump up against their bingo time before they can complete the mission. And if they have to leave anyone down in the water or in the damaged raft, that’s as good as a death sentence.

As if reading his mind, Nevada says, “Scott should be lowering the basket any second. Do you need a break? Do you want me to fly?”

“I’m okay.”

“You’re doing great.”

A gust rocks the helo. Nevada thinks, Thank God for our mechanics. He knows that all the hours of maintenance and repairs put in back at the air station make the difference between success or aborting the mission or even catastrophe. It’s going slow, Nevada reasons, but everyone is calm and doing their job.

• • •

“Turn him around!” shouts Drew, referring to JP. “I want his back by the edge of the raft!”

Rudy and Ben slide the unconscious captain around and to the side of the raft. Drew puts his arms under JP’s and pulls the survivor’s back in tight to his chest. He then uses his feet to push against the raft and drags JP out.

JP stirs, and his eyes flutter open. He’s got this awful sensation that someone is choking him, a sensation he is all too familiar with because that’s what his father would do to him to make a point. He’s too weak and confused to fight back. He feels like he’s in the water, but if that’s true, how could his father be choking him? A voice in his ear says, “We’re going for a basket ride.”

Drew has no idea whether JP has heard him or is processing what he’s saying. For now the rescue swimmer is relieved that the injured man isn’t moving. He has JP in what is called a cross-chest carry, with his right arm over JP’s right shoulder and his hand under JP’s left armpit. The maneuver allows him to tow JP a short distance from the raft.

Looking up at the helicopter, Drew gives the thumbs-up sign that he is ready for the basket. He knows Scott or the pilots have seen him because the aircraft immediately moves forward while descending. A wave partially breaks on the men, pushing them both under, and Drew does his best to raise JP’s head above the foam.

Scott slides the basket to the doorway. With his left hand, he pushes it outside the cabin while, with his right hand, he works the pendant, and the basket begins its descent. The wind blows it toward the back of the aircraft. Scott, who is now on his stomach, wrestles with the cable, pulling it forward so that the basket and cable don’t get pushed into the tail rotor or the external fuel tank.

Nevada is scanning the instruments and alerting the C-130 of their progress while keeping his eye on the clock and the oncoming waves. He’s growing fretful about the slow pace due to the seas. As quietly and calmly as possible, he says, “How’s it going back there, Scott?”

“Basket is being lowered,” gasps Scott.

From Drew’s perspective, the deployment is not going well. The basket is streaming about thirty feet behind the aircraft on about 130 feet of cable. Drew snatches a glimpse of Scott in the doorway, struggling with the cable. The Jayhawk slowly advances past his position in the ocean, bringing the trailing basket closer. Drew is having a hard time seeing the basket because of the foam scudding along the ocean’s surface like tumbleweed rolling through a desert. The downdrafts from the helicopter’s rotors add to the chaos, sending a swirling froth in all directions. Drew surges upward, using his flippers to gain a bit of height, and sees that the basket is only twenty-five feet away. He makes his move, knifing through the water with JP under one arm. Just a few feet before his objective, out of the corner of his eye, he sees a wave looming overhead. He grabs a bite of air before he and JP are pummeled by collapsing white water of such force that Drew is stunned and truly frightened. Whatever happens, don’t let go of this man, Drew tells himself. He’s not sure which way is up or down, but he tries to stay calm, knowing that the buoyancy in his dry suit, coupled with JP’s PFD, will bring them to the surface. When his head clears the foam, he has swallowed a good deal of seawater, and he wonders if the limp man in his arms is still alive. Drew treads water and steals a look at JP, noting his quivering purple lips, yet he’s surprised to see the survivor’s eyes open.

The basket is now far away, and Drew waits, knowing Scott will vector the pilots back into position, where the cage will be closer. He watches the aircraft maneuvering for another pass, determined not to miss the opportunity. When the basket is ten feet away, Drew rushes forward to grab it. This time he almost has a hand on its metal bars when the wave beneath him drops away, and rescue swimmer and survivor go sliding down its back side while the basket is airborne with no water beneath it.

Drew can’t believe it. He’s wasting valuable energy, and he doesn’t even have the first survivor in the basket. He has no idea how much time has gone by since he entered the water, but it seems like a lot. Ten minutes? Twenty minutes? And getting the survivor in the basket is sometimes the hardest part, particularly if the survivor can’t help in the process or if he resists, a distinct possibility with hypothermic survivors who cannot think clearly.

Up above, Scott is pissed. He’s still on his belly, straining against the gunner’s belt, holding the cable forward with his left hand while working the hoist with his right. Because the basket is far behind the helicopter, he has to keep his eyes on that spot rather than looking ahead for oncoming waves. He is conning the pilots into a position thirty feet in front of the men in the water below, but he is also listening for Nevada to warn him of any really big waves approaching. This is taking way too long. Wonder what the fuel situation is. Then he stops the thought sharply. That’s the pilots’ concern. Just focus on your job.

The aircraft crew members aren’t the only ones anxious about the passing time. Rudy and Ben, still in the drifting raft, are now far from the action. They can no longer see JP and the rescue swimmer, and with each passing wave, their glimpses of the helicopter are becoming briefer and briefer, until it’s mostly out of sight.

Rudy is cold to the core, and he’s having trouble gripping the raft’s lifeline. Something’s wrong, he thinks, but they won’t leave us. You made it this far, you can hang tough a little longer.

From left to right: Drew Dazzo, Scott Higgins, Nevada Smith, Aaron Nelson