Chapter 1

1. For the 1975 and 2009 figures on mothers’ participation in paid employment, see Tables 5 and 7 in U.S. Department of Labor & U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (December 2010) “Women in the Labor Force: A Databook” (Report 1026; http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-databook-2010.pdf). For 2009 figures for mothers with children under age 1, see Bureau of Labor Statistics (May 2010) Table 6 “Employment Status of Mothers with Own Children Under 3 Years Old by Single Year of Age of Youngest Child and Marital Status, 2008-09 Annual Averages” (http://bls.gov/news.release/famee.t06.htm). For figures on part-time work in 1975 and 2009 see table 20 in “Women in the Labor Force” report, cited above. For data on part-time work of women with infants in 2009, see Table 6 (cited above).

2. Alexander Szalai, ed., The Use of Time: Daily Activities of Urban and Suburban Populations in Twelve Countries (The Hague: Mouton, 1972), p. 668, Table B. Another study found that men spent a longer time than women eating meals (Shelley Coverman, “Gender, Domestic Labor Time and Wage Inequality,” American Sociological Review 48 [1983]: 626). With regard to sleep, the pattern differs for men and women. The higher the social class of a man, the more sleep he’s likely to get. The higher the class of a woman, the less sleep she’s likely to get. (Upper-white-collar men average 7.6 hours sleep a night. Lower-white-collar, skilled and unskilled men all averaged 7.3 hours. Upper-white-collar women average 7.1 hours of sleep; lower-white-collar workers average 7.4; skilled workers 7.0 and unskilled workers 8.1.) Working wives seem to meet the demands of high-pressure careers by reducing sleep, whereas working husbands don’t.

For more details on the hours working men and women devote to house-work and child care, see the Appendix of this book.

3. Grace K. Baruch and Rosalind Barnett, “Correlates of Fathers’ Participation in Family Work: A Technical Report,” Working Paper no. 106 (Wellesley, Mass.: Wellesley College Center for Research on Women, 1983), pp. 80-81. Also see Kathryn E. Walker and Margaret E. Woods, Time Use: A Measure of Household Production of Goods and Services (Washington. D.C.: American Home Economics Association, 1976).

4. Peplau, L. A., and K. P. Beals. “The Family Lives of Lesbians and Gay Men.” In A. Vangelisti, ed., Handbook of Family Communication, 2004.

Chapter 2

1. In a 1978 national survey, Joan Huber and Glenna Spitze found that 78 percent of husbands think that if husband and wife both work full time, they should share housework equally (Sex Stratification: Children, Housework and Jobs. New York: Academic Press, 1983). In fact, the husbands of working wives at most average a third of the work at home.

2. The concept of “gender strategy” is an adaptation of Ann Swidler’s notion of “strategies of action.” In “Culture in Action—Symbols and Strategies,” American Sociological Review 51 (1986): 273-86, Swidler focuses on how the individual uses aspects of culture (symbols, rituals, stories) as “tools” for constructing a line of action. Here, I focus on aspects of culture that bear on our ideas of manhood and womanhood, and I focus on our emotional preparation for and the emotional consequences of our strategies.

3. For the term “family myth” I am indebted to Antonio J. Ferreira, “Psychosis and Family Myth,” American Journal of Psychotherapy 21 (1967): 186-225.

4. F. T. Juster, 1986.

Chapter 3

1. Lee Rainwater and W. L. Yancey, The Moynihan Report and the Politics of Controversy (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press, 1967), p. 32.

2. In her book Redesigning the American Dream (New York: W. W. Norton, 1984), p. 91, Dolores Hayden describes how, in 1935, General Electric and Architectural Forum jointly sponsored a competition for who could design the best house for “Mr. and Mrs. Bliss”—the model couple of the period (Mr. Bliss was an engineer, Mrs. Bliss was a housewife with a college degree in home economics. They had one boy, one girl). The winner proposed a home using 322 electrical appliances. Electricity, the contest organizers proposed, was Mrs. Bliss’s “servant.”

3. Helen Gurley Brown, Having It All (New York; Simon and Schuster, 1982), p. 67.

4. Shaevitz, Marjorie H., The Superwoman Syndrome (New York: Warner, 1984), p. xvii.

5. Ibid., p. 112. All quotes within this paragraph are from ibid.

6. Ibid., pp. 205-6.

7. Ibid., pp. 100-101.

8. Hilary Cosell, Woman on a Seesaw: The Ups and Downs of Making It (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1985), p. 30.

9. Bob Greene, “Trying to Keep Up with Amanda,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 16, 1984, “People” section.

Chapter 9

1. The combination of high work demands with low control over the pace of these demands creates more strain in women’s jobs. This may account for the higher observed rates of mental strain among women workers— rates often implicitly attributed to “female frailty” or “excitability.” See Cranor et al. (1981).

Similarly, in their study “Women, Work and Coronary Heart Disease,” American Journal of Public Health 70 (1980): 133-41, Suzanne G. Haynes and Manning Feinleib suggest that women service workers (especially those married to blue-collar husbands, with three or more children) actually suffer more coronary disease than top-level male executives. These female workers combine the “low-autonomy” atmosphere of clerical work with the low-autonomy situation of the family-work speed-up. For research on the effect of marriage and work on mental stress, see Walter R. Gove, “The Relationship Between Sex Roles, Mental Health, and Marital Status,” Social Forces 51 (1972): 34-44; Walter Gove and Michael Geerken, “The Effect of Children and Employment on the Mental Health of Married Men and Women,” Social Forces 56 (1977): 66-76; and Peggy Thoits, “Multiple Identities: Examining Gender and Marital Status Differences in Distress,” American Sociological Review 51 (1986): 259-72.

2. One study found that male workers enjoy longer coffee breaks and longer lunches than female workers. According to Frank Stafford and Greg Duncan, men average over an hour and forty minutes more rest at work than women do each week. See Frank Stafford and Greg Duncan, “Market Hours, Real Hours and Labor Productivity,” Economic Outlook USA, Autumn 1978, pp. 103-19.

3. Wiseman, Paul. “Young, Single, Childless Women Out-earn Male Counterparts,” USA Today, September 2, 2010. Figures are based on U.S. Census Bureau information analyzed by the New York research firm Reach Advisors.

4. Blades, Joan, and Kristin Rowe-Finkbeiner, The Motherhood Manifesto, New York: Nation Books, 2006, p. 7.

Chapter 10

1. See Nancy Chodorow, The Reproduction of Mothering (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980).

Chapter 13

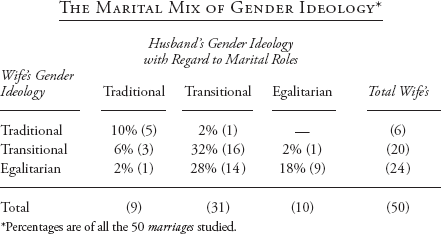

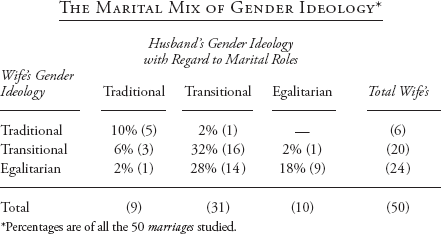

1. Of the 100 men and women in the 50 “mainstream” couples I studied, 18 percent of the husbands were traditional, 62 percent transitional, and 20 percent egalitarian. Among the wives, 12 percent were traditional, 40 percent were transitional, and 48 percent were egalitarian. (Berkeley couples were omitted because they probably reflect an untypically liberal subculture.) Below, I’ve shown how husbands’ gender ideologies match those of their wives.

Thus, of all the marriages I studied, 60 percent were between husbands and wives who shared similar ideologies, and 40 percent were between husbands and wives who disagreed. The most common type of disagreement was between an egalitarian woman and a transitional man.

Chapter 14

1. See William J. Goode, “Family Disorganization,” Chapter 11 in Contemporary Social Problems, 4th ed., Robert K. Merton and Robert Nisbet (eds.) (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976). Also see Louis Roussel, Le Divorce et les Français, Vol. II, “L’Expérience des Divorcés,” Travautet Documents, Cahier No. 72 (Presses Universitaires de France, 1975), pp. 26-29. In many ways, the fact that wives work both benefits and stabilizes marriage. In virtually all the research on women’s work, working women report themselves as happier, higher in self-esteem, and in better mental and physical health than do housewives. See Lois Hoffman and F. I. Nye, Working Mothers (San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 1974), p. 209. A woman’s work also adds money to a marriage through the so-called dowry effect. By making a family richer, a woman’s wages may protect the family from the strains of poverty associated with marital disruption. See Valerie Kincade Oppenheimer, “The Sociology of Women’s Economic Role in the Family,” American Sociological Review 42 (1977): 387-405; D. T. Hall and F. E. Gordon, “Career Choices of Married Women,” Journal of Applied Psychology 58 (1973): 42-48.

2. Ronald C. Kessler and James McRae, Institute for Social Research Newsletter, University of Michigan, 1978. See also S. S. Feidman, S. C. Nash, and B. G. Aschenbrenner, “Antecedents of Fathering,” Child Development 54 (1983): 1628-36; M. W. Yogman, “Competence and Performance of Fathers and Infants,” in A. Macfarlane, ed., Progress in Child Health (London: Churchill Livingston, 1983).

3. Joan Huber and Glenna Spitze, Sex Stratification: Children, Housework and Jobs (New York: Academic Press, 1983).

4. According to George Levinger’s study, men voiced fewer complaints. But the top four were mental cruelty (30 percent), neglect of home or children (26 percent), sexual incompatibility (20 percent), and infidelity (20 percent). For women, the top four were mental cruelty (40 percent), neglect of home or children (39 percent), financial problems (37 percent), and physical abuse (37 percent). (“Sources of Marital Dissatisfaction Among Applicants for Divorce,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 36 [1966]: 803-7.)

Chapter 15

1. Other studies find that a man’s upbringing bears only a slight relationship to the amount of work at home he does as an adult. See Lois Hoffman, “Parental Power Relations and the Division of Household Tasks,” in F. I. Nye and L. W. Hoffman, eds., The Employed Mother in America (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1963), pp. 215-30; M. Bowling, “Sex Role Attitudes and the Division of Household Labor,” paper presented at the American Sociological Association, Chicago, 1975; Rebecca Stafford, Elaine Backman, and Pamela DiBona, “The Division of Labor among Cohabiting and Married Couples,” Journal of Marriage and the Family 39 (1977): 43-57; C. Perucci, H. Potter, and D. Rhoads, “Determinants of Male Family Role Performance,” Psychology of Women Quarterly 3 (1978): 53-66; M. Roberts and L. Wortzel, “Husbands Who Prepare Dinner: A Test of Competing Theories of Marital Role Allocations,” unpublished paper, Boston University, 1979; S. Hesselbart, “Does Charity Begin at Home? Attitudes Toward Women, Household Tasks, and Household Decision-Making,” paper presented to the American Sociological Association, 1976; and Gayle Kimball, 50-50 Marriage (Boston: Beacon Press, 1983).

2. Surprisingly, most researchers find little or no relationship between the amount of time a man spends at paid work and the proportion of housework he does. See Robert Clark, Ivan Nye, and Viktor Gecas, “Husbands’ Work Involvement and Marital Role Performance,” Journal of Marriage and the Family 40 (1978): 9-21; Stafford, Backman, and DiBona (1977); Perucci, Potter, and Rhoads (1978). But also see John Robinson, How Americans Use Time (New York: Praeger, 1977), and Walker and Woods (1976). For a thorough review of the evidence, see Joseph H. Pleck, Working Wives, Working Husbands (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1985), p. 55.

3. I found a slight—but not statistically significant—difference. Despite a good deal of research on the possible link between the wage gap between husband and wife and the leisure gap between them, I’m aware of only one researcher, the economist Gary Becker (A Treatise on the Family [Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981]), who found such a link. For more on research about this link, see the Appendix.

4. Pleck (1985), p. 151.

5. See Bob Kuttner, “The Declining Middle” Atlantic Monthly, July 1983; Paul Blumberg, Inequality in an Age of Decline (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980); Michael Harrington and Mark Levinson, “The Perils of a Dual Economy,” Dissent 32 (1985): 417-26; and Andrew Hacker, “Women Versus Men in the Work Force,” New York Times Magazine, December 9, 1984. For the argument that the labor market is not dividing into two parts, see Neal H. Rosenthal, “The Shrinking Middle Class: Myth or Reality?” Monthly Labor Review 108 (1985): 3-10.

6. Sheila B. Kamerman and Cheryl D. Hayes, eds., Children of Working Parents: Experience and Outcomes (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1983), p. 238.

7. See Norma Radin, “Primary Caregiving and Role Sharing Fathers of Preschoolers,” in M. E. Lamb, ed., Nontraditional Families: Parenting and Child Development (Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1982), and her “The Role of the Father in Cognitive/Academic Intellectual Development,” in M. E. Lamb, ed., The Role of the Father in Child Development, 2nd ed. (New York: Wiley, 1981); Norma Radin and Graeme Russell, “Increased Father Participation and Child Development Outcomes,” in Lamb, Nontraditional Families, pp. 191-218; H. B. Biller, “The Father and Personality Development: Paternal Deprivation and Sex-Role Development,” in M. E. Lamb, The Role of the Father in Child Development (New York: Wiley, 1976); A. Sagi, “Antecedents and Consequences of Various Degrees of Paternal Involvement in Child-Rearing: The Israeli Project,” in Lamb, Non-traditional Families, pp. 205-32; and Michael E. Lamb, ed., The Father’s Role: Applied Perspectives (New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1986). In Robert Blanchard and Henry Biller’s study of forty-four white third-grade boys, they compared boys whose fathers were absent before they were five, absent after five, present for less than six hours a week, and present for more than two hours a day. The boys were similar in their age, I.Q., social class, and the presence of male siblings. The boys who saw their fathers the most did much better on the Stanford Achievement Tests (which measure comprehension of verbal, scientific, and mathematical concepts) than did boys whose fathers were involved less than six hours a week, and did much better than boys whose fathers were totally absent (“Father Availability and Academic Performance Among Third-Grade Boys,” Developmental Psychology 4 [1971]: 301-15).

8. Carolyn and Philip Cowan found that a father’s involvement increased his daughter’s sense of being master of her fate and improved her scores in math (“Men’s Involvement in Parenthood: Identifying the Antecedents and Understanding the Barriers,” in P. Berman and F. A. Pedersen, eds., Fathers’ Transitions to Parenthood [Hillsdale, NJ.: Erlbaum, 1986]).

9. See Mark W. Router and Henry B. Biller, “Perceived Personality Adjustment Among College Males,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 40 (3) (1973): 339-42.

Chapter 16

1. Alice Kessler-Harris, Out to Work (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982). Also see Julie A. Mattaie Bradby, An Economic History of Women in America (New York: Schocken Books, 1982).

2. Louis Harris and Associates, “Families at Work,” General Mills American Family Report, 1980-81. Other research also shows that even working-class women who do not have access to rewarding jobs prefer to work. See Myra Ferree, “Sacrifice, Satisfaction and Social Change: Employment and the Family,” in Karen Sacks and Dorothy Remy, eds., My Troubles Are Going to Have Trouble with Me (New Brunswick, NJ.: Rutgers University Press, 1984), pp. 61-79. Women’s paid work leads to their personal satisfaction (Charles Weaver and Sandra Holmes, “A Comparative Study of the Work Satisfaction of Females with Full-Time Employment and Full-Time Housekeeping,” Journal of Applied Psychology 60 [1975]:117-28) and—if a woman has the freedom to choose to work or not—it leads to marital happiness. See Susan Orden and N. Bradburn, “Working Wives and Marriage Happiness,” American Journal of Sociology 74 (1969): 107-23.

3. See U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports: Households, Families, Marital Status and Living Arrangements, series P-20, no. 382 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1985). Also see Statistical Abstracts of the U.S. National Data Book, Guide to Sources (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1985). Spousal support is awarded in less than 14 percent of all divorces, and in less than 7 percent of cases do women actually receive it. See Lenore Weitzman, The Divorce Revolution (New York: Free Press; London: Collier Macmillan, 1985).

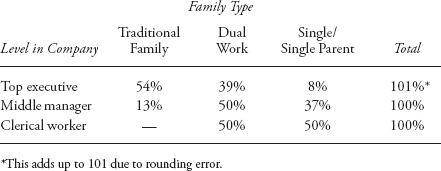

4. These findings are based on questionnaires I passed out to every thirteenth name on the personnel roster of a large manufacturing company. Of those contacted, 53 percent replied. The results show that the typical form of a worker’s family life differs at different levels of the corporate hierarchy. The traditional family prevails at the top. Dual-work families prevail in the middle, and single-parent families and singles prevail at the bottom, as the chart below shows:

Chapter 17

1. “What Do Cal Freshmen Feel, Believe, Think?” Cal Report 5 (March 1988): 4. In her study of Barnard senior women, Mirra Komarovsky found only 5 percent wanted to become housewives (Women in Colleges: Shaping New Feminine Identities [New York: Basic Books, 1985]).

2. See Anne Machung, “Talking Career, Thinking Job, Gender Differences in Career and Family Expectations of Berkeley Seniors,” Feminist Studies 15 (1), Spring 1989.

3. Public Opinion, December-January 1986.

4. Machung (1989).

5. For more on the role of Soviet men in housework and child care, see Michael Paul Sacks, “Unchanging Times: A Comparison of the Everyday Life of Soviet Working Men and Women Between 1923 and 1966,” Journal of Marriage and the Family, November 1977, pp. 793-805; and Gail Lapidus, ed., Women, Work and Family in the Soviet Union (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1982).

Afterword

1. Katrina Alcorn, Huffington Post Internet Post, April 8, 2010, “Peaceful Revolution: If You Give a Mouse a Prozac…”

2. Tina Fey, “Confessions of a Juggler,” The New Yorker, February 14, 2011, p. 64.

3. Compared with the 1980s, fewer mothers are married, have preschool kids, and work full time. If we follow the statistics, it seems more have quit, cut back hours, or divorced. Still, whether married, cohabiting, or divorced, most mothers of preschool children—six out of ten mothers of children under three—are in the labor force. And of those, only a quarter (27 percent) work part time. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, Table 6, “Employment Status of Mothers with Own Children Under 3 Years old by Single Year of Age of Youngest Child, and Marital Status, 2007-2009 Annual Averages.”

4. The combined weekly work hours of married couples has risen by 20 percent—from fifty-six hours a week in 1969 to sixty-seven hours in 2000. Based on a Bureau of Labor Statistics study, the figures apply to couples ages twenty-five to fifty-four. “Working in the 21st Century” (http://www.bls.gov/opub/working/page17b.htm). According to a 2009 Time Use survey, employed men work now, as in the past, about an hour more than employed women, and even among full-time workers (men average 8.3 hours and women 7.5). “American Time Use Survey” 2009 (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/status.nr0.htm). On hours of work for employed women and men, 1980 to 2009, see the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor, “Women in the Labor Force, 2010,” Table 21 (http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-table21-2010.pdf).

5. Teresa Ciabattari, Gender and Society, August 2001, 15(4): 574-91, Table 3. Another study based on the nationwide General Social Survey showed a similar rise in the acceptance of the equality of the sexes between 1974 and 2004. But it also revealed a pause in 1994 and subsequent flattening of the upward trend through 2004. This pause did not signal, the authors surmise, a return to 1950s domesticity, but rather a shift that Maria Charles and David Grusky call “egalitarian essentialism.” This view mixes the new (women should have equality of choice) with old (women are better with children and should choose to stay home when they can). Women can be equal, this view holds, and stay home with the children because they’ve freely chosen to do so. These choices are often premised, of course, on the assumption that we can’t reshape jobs, get more government support, and alter the prevailing notion of manhood.

6. Scott Coltrane, “Research on Household Labor: Modeling and Measuring the Social Embeddedness of Routine Family Work,” Journal of Marriage and Family 2000, 62(4): 1208-33. Studies tracking the years between 1969 and 1999 reported men doing some more housework (an annual 262 hours more) and women doing quite a lot less (783 hours less). The housework gap between the sexes shrank in those decades from thirty-three hours a week to less than thirteen. See “Time Use: Diary and Direct Reports” by F. Thomas Juster, Hiromi Ono, and Frank. P. Stafford (Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, unpublished report, Tables 9 and 10, pp. 39-49).

7. See Melissa A. Milkie, Sara B. Raley, Suzanne M. Bianchi, “Taking on the Second Shift: Time Allocations and Time Pressures of U.S. Parents with Preschoolers,” December 2009, Social Forces, 88(2): 487-518.

8. Ibid, p. 502. If the researchers added in what they call “secondary activities”—tasks one did while also doing other things—they found women working an extra 9.3 hours per week, or extra 20 days a year. Ibid., Table 2, p. 517.

9. “Child Poverty in Perspective: An Overview of Child Well-being in Rich Countries,” UNICEF, Innocenti Report Card 7, Florence, Italy, 2007 (http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/rc7_eng.pdf).

10. Ibid, p. 2, for overall rankings. The United States, along with the United Kingdom ranked in the bottom third in five out of the six dimensions reviewed. The Netherlands won highest marks. There was no relationship between how rich a country was and the welfare of its children. The Czech Republic outranked the United States, for example.

11. Ibid, p. 37.

12. International Labour Office, Bureau for Gender Equality, Gender Equality and Decent Work: Good Practices at the Workplace, 2005.

13. Joan Blades and Nanette Fondas, The Custom-Fit Workplace, 2010: San Francisco: Jossey Bass.