A HUMAN LIFE IS A SERIES of experiences. When we have little awareness of our predicament, experiences feed our attachments and condition our desire for more experiences. Our perspective changes when we begin to sense, even momentarily, the unity of all things and our identity with the Self.

We start to see each experience as a teaching to be brought into awareness and loved until we are free from being captivated by the experience. As we begin to awaken, experiences lead to reflection and contemplation. Then as we become more aware, experiences become a fire of purification, a burning ground of the ego, grist for the mill of developing consciousness, food enabling the emerging soul to break free of its bonds.

What is the nature of the mind stuff that keeps us in our egos? Ego attachments may be habits of thought, the residue of experiences, desires we’ve developed and reinforced or that have been implanted, even unconscious urges and tendencies.

Attachments conspire to create this stuck-together bundle of changing thought forms and feelings we label a self, our ego. This sanguine idea of self is just that, an idea, a description of how we’re doing at the moment, self-inflated or disappointed, a conglomeration of thoughts, feelings, and concepts that changes all the time. One morning I wake up thinking about enlightenment. The next morning I wake up thinking about world politics and environmental disasters. The next day I’m anxious about getting this book done. These temporal experiences that form our ego are like flickering images of a passing show. Each one seems real at the time, but they keep changing.

The Self is the witness, all-pervading, perfect, free, one consciousness, actionless, not attached to any object, desireless, ever tranquil. It appears through illusion as the world.

—Ashtavakra Gita I:12

One of the first steps in getting free of the attachment to this ego idea is to develop a witness. We have thousands and thousands of me’s, but there is one me that is separate and watches all the other me’s. It’s on a different level of consciousness. It’s not just another role; it’s part of the heart-mind.

This witness is your leverage in the game. The witness me isn’t trying to change any of the other me’s. It’s not an evaluator or a judge; it’s not the superego. It doesn’t care about anything. It just observes. “Hmmm, there she or he is doing that again.” That witness place inside you is your centering device, your rudder.

The witness is part of your soul. It’s witnessing your incarnation, this lifetime, from the heart-mind. It’s the beginning of discrimination between your soul and your ego, your real Self and your self in the incarnation. Once you begin to live in this witness place, you begin to shift your identification from the roles and thought forms. As you witness yourself, the process becomes more like watching a movie than being the central character in one.

As you begin to dwell in Self-awareness, the old identifications with ego roles begin to just fall away. You shift your identification from the external roles and attachments to internal awareness. It’s a being thing, not a doing thing.

You don’t do anything. I once asked Dada Mukerjee, one of Maharaj-ji’s oldest and closest devotees, how to give up attachments. He said, “Well, you can give things up, or you can wait until they give you up.” Dada was a lifelong smoker, and though smoking was definitely not allowed in an ashram environment, Maharaj-ji very lovingly allowed him time and space to drop out of sight for an occasional cigarette. After Maharaj-ji left the body, Dada just stopped smoking.

The ego is based on fear, but the soul is based on love. Maharaj-ji is teaching us about soul. He’s acknowledging our souls. As you witness your ego stuff, one way to release it is to constantly offer it into the fire of love in your heart. I am loving awareness.

Another mantra I have used to get into witness awareness and see the ego from the God perspective is: I am a point of sacrificial fire held within the fiery will of God. I received this mantra from Hilda Charlton, a teacher in New York who was a chela, or disciple, of Nityananda, whom you will meet later. She held a weekly class at St. John the Divine in Manhattan that helped countless people keep their spiritual heads above water. In her youth Hilda was a modern dancer. She traveled to India in the 1940s and danced in maharajas’ courts to support herself. She was a strong teacher, and this is a fierce mantra to work with. Nityananda, her guru, was a great Shaivite siddha, a realized being who followed Shiva, the destroyer. He was also full of boundless love and compassion.

As you continue with your sadhana, as meditation deepens, you identify less and less with the ego and begin to touch and enter more deeply into the space of love. You begin to experience love toward more and more people and find love in the experiences that come into your field of awareness.

When Maharaj-ji said, “Ram Dass, love everybody,” I said, “I can’t.” That was my ego talking. He said, “Love everybody.” He wasn’t listening to my ego. In that moment I saw my dying ego and who I was becoming. I looked between him and me and had a vision of a coffin, and my old self was in the coffin. I had to give up. He just wasn’t going to honor my ego any longer.

As you keep giving up the habits that hold you back from loving, the ego’s fear of letting go dissolves in the love. From the ego’s vantage point you surrender into love. From the soul’s vantage point you are coming home, the boundaries of separation are fading, and the two are becoming one. As you begin to enter into Oneness and to become love, instead of perceiving from your ego, you’re perceiving from your soul. You are shifting your identification from ego to soul. You don’t kill your ego; you kill your identification with your ego. As you dissolve into love, your ego fades. You’re not thinking about loving; you’re just being love, radiating like the sun. That last step requires Grace.

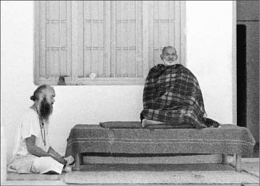

Ram Dass and Maharaj-ji. Photo by Rameshwar Das.

The Pressure Cooker

Although it often seemed like nothing was happening around Maharaj-ji, a lot was going on for everyone. It was an incredible space where most of what was happening was internal and little of it external. It was like a great river, like the Mississippi or the Colorado—beneath a calm opaque surface turbulent waters carry great rocks and tons of sediment and mud, carving out entire landscapes. As we sat around seemingly doing nothing, the changes beneath the surface felt truly geological, or neurological, as if Maharaj-ji was rewiring us on a subtle level.

Most of the time while we were sitting with Maharaj-ji, he was carrying on mundane conversations with devotees about families, jobs, weddings, or health. Meanwhile I might be going through an exquisitely painful memory or riding an emotional roller coaster. Every once in a while there would be a twinkle of recognition from Maharaj-ji, a piece of fruit thrown directly at me, a penetrating glance, an acknowledgment that told me he still knew everything that was going on. This happened a lot.

Many of us had come to him from transformative experiences with psychedelic drugs. However, our faith in him was not built on episodes of being high, which have inherent within them the seeds of disappointment and loss, because you always come down. Instead, he kept us down as he kept burning out our fears and neuroses and attachments, and at the same time we kept seeing the depth of our love for him. It built a base of love and trust, which you might call faith.

For example, I was carrying a burden of doubt when I returned to India to see Maharaj-ji in 1970. In America a boy who had been my student had died. He was a deeply spiritual kid whose father was a foreign scientist. The family was well off and had homes in New Hampshire and Arizona. The boy lived in New York, but had gone to do sadhana in a cave on their place in Arizona. Later I heard from his mother that he had died.

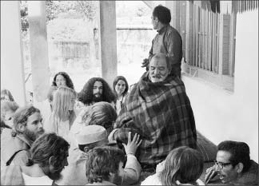

Westerners with Maharaj-ji. Photo by Rameshwar Das.

The mother said, “My son has achieved mahasamadhi (final merging).” She showed me the diary that he had kept. He wrote that he was taking samadhi, that she should not worry, and that he would be watching over her. She asked me, “Is everything he said true?”

I said, “Well I don’t know, but I’m going back to India in the fall to see my guru, and he will certainly know.”

I had my doubts. No student of mine had gained mahasamadhi, and I said to myself that it must be drugs. Later I learned he had indeed taken LSD. There had been blood on the walls of the cave, and I assumed he had tried to do pranayama (yogic breath control) while on LSD and had overdone it.

One day we were all showing our photos to Maharaj-ji, passport photos and pictures from our wallets. I remembered I had this boy’s photo and went to get it. It was his high-school graduation picture. It didn’t look much like the way I remembered him, but I put his picture next to Maharaj-ji, who said, “He left his body.” Then he proceeded to quote from the boy’s diary: “Tell Ram Dass I have finished my work. I will be watching over you, Mother,” and he gave me all the information from the diary. Maharaj-ji said, “He’s one with Christ. He has finished his work. He’s watching over his mother.”

Then he said, “Your medicines weren’t the cause of his death.” His death had been weighing on my mind. I wrote to the mother and told her that Maharaj-ji had affirmed what her son had written to her. This is just one instance of how Maharaj-ji worked with the subtleties of our lives beyond appearances to confirm our faith.

He also worked on us through our relationships with one another, sometimes calling one or two or all of us down during the day for some conversation or teaching or to use us as examples in some teaching or melodrama with the Indian devotees. Late in the afternoon we would see him for a final gathering before catching the last bus back to town.

One day Maharaj-ji appointed me “commander-in-chief” of the Westerners. I was supposed to keep everybody in line and get everybody on the bus. It was like herding cats. Somebody like Krishna Das would want to stay at the temple. So he asked Maharaj-ji, and Maharaj-ji gave his blessing for him to stay over. What was going on here? My authority was being thwarted! My feeling of importance as commander-in-chief deflated like a balloon.

Once when we were in Allahabad, Maharaj-ji told me to bring everyone to the house where he was staying at 6 P.M. Some rascals went early. When I got there with those who had dutifully followed my lead, the early birds were all having a great time with Maharaj-ji. Upon our arrival he promptly went into his room, and we didn’t see him the rest of the evening.

He kept pulling the rug out from under me every time I tried to establish my power. It was playful, but it left my ego nowhere to stand. I had to choose between my ego pride and my love for him. I struggled with the pride, before my heart made the choice. I continued along with the commander-in-chief farce, but I stopped taking it seriously.

We spent the most time with Maharaj-ji at Kainchi, a beautiful temple in the Himalayan foothills. On my first visit, in 1966–67, I was there almost alone through the winter months learning yoga and absorbing a new worldview. It was intensely solitary.

When I returned in 1970, a group of Westerners was already there. From the outside the scene must have seemed idyllic. The temple was in a valley with a river, quiet countryside, good food, warm sun. But it was not a restful scene. There was a quality of nervous tension and the tremendous energy of Maharaj-ji’s presence, whether we were physically with him or not. It was like a pressure cooker.

Our tensions with one another were incredible too, some from the discomforts of dysentery, hepatitis, and other ailments and some from the difficulty of adjusting to Indian culture. Maharaj-ji kept the pressure going. There were jealousies, rivalries, and feelings of competition for Maharaj-ji’s attention and affection among the Westerners. As if we had any ability whatsoever to influence that! It was all his lila, his dance! The closer we got to those higher states of energy and consciousness, the more it seemed as though our imperfections gained energy too. We started to call it the Grace Race.

Relations between Westerners and Indians were sometimes tense too, whether from our inadvertent transgressions of cultural mores or possibly their feelings that the crazy videshis (foreigners) were usurping Maharaj-ji. You couldn’t tell; everybody was always going through something. Maharaj-ji usually acted as if he had nothing to do with it, but we knew he was behind it all.

These situations kept hitting us where we lived. If there was a place where we were holding on, it soon became obvious. Sometimes Maharaj-ji was very fierce, sometimes cold, sometimes warm and humorous, as if to tell us not to take ourselves so seriously. And all of it was part of his lila and his work with each of us to get us free. Maharaj-ji was present for many people on many levels at the same time. He could be talking with one person, and we would each be receiving the teaching we needed and interpreting it according to our own situation.

Dealing with Our Stuff

We can’t mask impurities for very long. When we suppress or repress them, they gain energy. Eventually we all have to deal with our same old karmic obstacles. Maharaj-ji used to enumerate them with regularity: kama, krodh, moha, lobh—lust, anger, confusion, and greed. It’s the spectrum of impulses and desires that condition our interior universe and our view of reality. We have to take care of this stuff, so we can climb the mountain without getting dragged back down.

This clearing out opens the door for dharma, for being in harmony with the laws of the universe on both a personal and social level. If you do your dharma, you do things that bring you closer to God. You bring yourself into harmony with the spiritual laws of the universe. Dharma is also translated as “righteousness,” although that evokes echoes of sin and damnation. It’s more a matter of clearing the decks to be able to do spiritual work on yourself.

The niyamas and yamas, the behavioral dos and don’ts of Patanjali’s yoga system, are a functional approach to dharma that is useful without being judgmental. You do what will take you closer to God, the One, and don’t do what takes you further away. The dos, the niyamas, are: sauca, cleanliness or purity; santosha, contentment; tapas, austerity or religious fervor; swadhyaya, study; and ishwara pranidhana, surrender to God. Even the don’ts, the yamas, are framed as positive qualities to be cultivated: ahimsa, nonviolence or harmlessness; satya, truthfulness or nonlying; asteya, nonstealing; brahmacharya, continence or not being promiscuous; and aparigraha, noncovetousness or freedom from avarice. There are many subtle issues surrounding these practices, of course, but those are the basics.

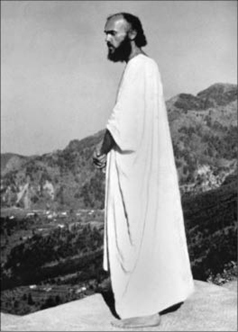

Ram Dass. Photo courtesy of Ram Dass.

When I was first at the temple in the Himalayas, I was taught these practices by Hari Dass Baba, whom Maharaj-ji assigned to teach me yoga. He wrote on a chalkboard, because he kept silence. He was very sweet, but the niyamas and yamas seemed like an almost Victorian moral code. As I learned more of yoga though, I began to see how these spiritual disciplines fit into the puzzle.

By the time I had practiced the niyamas and yamas for six months, I felt much lighter. In my eyes I was beginning to become a true yogi. By directing my attention away from the distractions of the outer world, the niyamas and yamas were helping me to be more one-pointed in my inner journey.

This was a period of intense practice for me, in relative solitude in an ashram. But this stuff never really goes away. When I returned to the “marketplace” of the West, all the usual distractions were there. Maybe they didn’t pull me quite as much, and I was no longer as completely fascinated by every desire. This is what the niyamas and yamas do—they create a perspective and help you focus on the deeper satisfaction from the spirit. For instance, brahmacharya, which is often translated “celibacy,” actually means “linked to God.” You might be celibate, but it’s because you’re into God, not because there’s anything negative about sex. It gets subtle, and the work is ongoing. Even now, I am still wrestling with contentment in my old age.

My Spiritual Scrapbook

As you pass through life on the way to God, what’s important is not what you experience, but how you identify with or cling to what you experience. Depending on your method, an experience may be figure or ground on your individual path. An experience may become a dominant theme, or it may be irrelevant. For example, when I was studying vipassana, or insight meditation, in Bodh Gaya, where Buddha became enlightened, with S. N. Goenka and Anagorika Munindra, pressure began to build up in my forehead. I thought it was a big spiritual advance, and I was thrilled at the prospect that my ajna, my third eye, was opening.

Goenka said, “That’s just blocked energy. It’s no use to you. Go out into the garden, run it down your right arm and out through your fingertips, and send it into the earth.”

I followed his instruction. I saw a blue light come out of my fingertips, and the pressure was gone from my forehead. I missed it. But in the vipassana system it was irrelevant. In a shakti, or energy-oriented, system you would focus on it, push it higher, and work with the energy.

I have built my house in the stainless. I am merged in the formless. I am one with the illusionless. I have attained to unbreakable unity. Tuka says, now there is no room for egoism. I am identified with the Eternally Pure.

—Tukaram1

Ultimately every method gets you to the same place. There are many paths up the mountain, but the peak is the same. You don’t notice this at the bottom. We don’t hear much about the advanced part of most systems, because few people get to the peak.

An experienced Buddhist meditator told me that only after he meditated for many years was he ready to do metta, the meditation of loving-kindness, which opened his heart. He was only ready for the heart after he had quieted his mind. That was my experience too. After I got to a degree of concentration in vipassana, I was able to return to Maharaj-ji with a more one-pointed love.

On the other hand, if you are a bhakti practitioner, only when your heart is so absorbed in loving the Beloved does your mind become capable of merging. You get there from another direction. You go up the mountain from a different side, but the view from the top where love merges with awareness is One.

To a subtle diagnostician of spiritual progress these experiences are all clues to where you’re not—yet. From the summit all these states are available, but you’re not clinging to any of them. You don’t define yourself in terms of any of them. You’re all of them, and you’re none of them. You’re no longer stuck in being the experiencer. It’s all just here.

Merging into Oneness transcends experience. That scares the hell out of people who are stuck in their ego. The ego doesn’t want that. The ego just wants to keep collecting more and more subtle experiences as a separate self. It makes people think the journey is just one subtle experience after another. The spiritual journey isn’t like that.

It’s scary for the ego when you start to merge. When I sat with Maharaj-ji once and the energy started to rise, I started shaking so hard, I was afraid I’d break my neck. He said, “He’s not ready,” and the energy or whatever it was stopped. I saw the way my mind was holding me back. I still had work to do.

Our human conditioning makes the ego react against threats to survival. The experiencer experiences fear when the experiences disappear. That’s why there aren’t very many liberated beings—because you have to let go. Lots of people like to be seeking God, but not too many want to actually get there.

The Five-Limbed Yoga

When we were with Maharaj-ji in India at Kainchi, generally we would go out to the temple on the early morning bus from Nainital. Only a few of us at a time were ever allowed to stay at the temple when Maharaj-ji was there. More Westerners did later, but I didn’t. On arrival we would enter and pranam, or greet, the temple deities, and if Maharaj-ji was out on his tukhat, or wooden bed, under the portico, we would go up, pranam, and give him the apple or whatever offering we had brought.

With regard to practice, that time with Maharaj-ji defies easy description. Maharaj-ji gave few specific teachings, and our routine was largely a formless improvisation that revolved around him. There were the daily rituals in the temple, but for the Westerners the days would pass in a blissful cloud focused on him. Western minds being irrepressible, eventually one of our number dubbed this unscripted play “Maharaj-ji’s Five-Limbed Yoga” (the classical raja, or ashtanga, yoga is eight-armed). The five limbs were Eating, Sleeping, Drinking Tea, Gossiping, and Walking About.

To a poor person God appears in the form of food.

—Maharaj-ji

Although the intent of such a description was humorous, these simple daily acts were charged with significance in the intense atmosphere that pervaded the little temple in the Himalayan valley. Maharaj-ji might be talking to somebody, ignoring us, and we’d just sit there quietly and look at him. Sometimes he’d accept the apples and throw them back to us or start a conversation about something that was going on in our lives at that moment. Sometimes he’d just sit quietly with us. Those were precious moments. After a little while he might order tea for us, one of the ashram staff would bring a teapot, and we would drink it in front of him. Once, someone asked Maharaj-ji how to get rid of attachments, and he answered, “You want tea? Don’t take it.”

Usually he would send us to rooms in the back of the temple, where we stayed much of the day. At lunch we were fed copious quantities of puris and spicy potatoes and sometimes Indian sweets. That food satisfied an inner hunger besides nourishing our bodies.

Maharaj-ji officiated from a distance over the kitchen, checking and overseeing everything. Food would be offered to him before being served to anyone else, and he would bless it. He taught us that food had to be cooked with love or it would be poison. He often said people had to fill their stomachs before they could think about God.

Maharaj-ji made sure just the right amount of food was prepared every day. Nothing was wasted, everything was consumed, and nothing was kept for the next day. Maharaj-ji told the cooks in the kitchen how many people to expect. He ran a tight ship. Feeding people was a big part of his teaching.

After lunch there was often a rest period or nap time. Some would read and others would snooze; sometimes the urge to sleep was overpowering. Those naps often became forays into the unconscious and astral planes. Vivid dreaming was common. Sleep wasn’t time off, but a kind of teaching on other planes. We were just wrapped in the embrace of all that shakti, or cosmic energy. Then we’d see Maharaj-ji again in the afternoon for kirtan chanting or darshan before we took the last bus back to Nainital.

“Serve the poor,” Maharaj-ji said.

“Who is poor, Maharaj-ji?”

“Everyone is poor before Christ.”

Occasionally Maharaj-ji would call one or another of us up to demonstrate for the Indian devotees how we had come all the way from America on a true spiritual quest, often holding us up as absurdly pure examples to tease the Indians about their supposed impurities. Sometimes he would have us perform the Hindu prayers or songs we had learned to show how devout and holy we were. Everyone delighted in this charade, which would sometimes be repeated for days on end as new audiences arrived and we learned the chants. Wanting to perform well, we learned the prayers quickly.

Once I was called in while Maharaj-ji was talking with a High Court judge. I was introduced as the Harvard professor. The judge invited me to visit the High Court, which, of course, I had no desire to do. My father and brothers were all lawyers, and I knew the lay of that land. Trying to be polite I said, “Oh, delightful!”

Maharaj-ji mimicked my response. “Delightful!” he said. “If Ram Dass says it will be delightful, of course, he’ll come.”

At the High Court I visited the lawyers’ room, and, having read Time magazine, I held forth about Nixon’s visit to China. This was just after India’s brief border war with China, and it was a hot-button topic. The next day one of the lawyers came and asked if I would like to speak to the Bar Association.

Eating on the veranda. Photo by Rameshwar Das.

Finally catching on, I said, “Well, you’ll have to ask my guru.”

So he asked Maharaj-ji if I could speak to the Bar Association about Nixon and China.

“Oh no,” said Maharaj-ji. “You can’t trust Ram Dass to talk about important things. He only can talk about me or spiritual things.”

Then the lawyer said, “Oh. Well, then we won’t have him come. He’ll come to my house sometime to talk to a few lawyers about spiritual things.”

Tea, or chai, served milky and sweet in unfired earthenware cups, appeared every few hours. It was strong and tasted slightly of the clay dust in the cups. It kept us in a state of high alert, or at least more alert than we would have been otherwise. I think India runs on chai and betel nut. One of Maharaj-ji’s old devotees, “Hemda” Joshi, was fond of saying, “There’s always time for tea!” Sipping tea was also an opportunity to socialize and exchange stories, deepening those mysterious bonds of spiritual family.

Gossip, mostly about Maharaj-ji, helped create and sustain the mood; it was a thread that held together the disparate band of Westerners, some of whom had strong personalities. Comparisons to other spiritual scenes, rumors of interpersonal attractions, not so subtle rivalries—it all came out in the wash of words and thoughts we exchanged.

In the summer of 1971 a few of us planned to undertake a rainy-season meditation retreat with Anagorika Munindra, a Buddhist teacher, at Lakshmi Ashram, where he used to stay every summer on a hilltop in the Himalayan village of Kausani. Before we left for Kausani, I proudly told Maharaj-ji we were going to study Buddhist meditation. He said, “As you like,” leaving us to follow the winding path of our own desire.

Kausani has an incredible panoramic view of the Himalayan peaks, but they were almost always obscured by monsoon clouds at that time of year, so there were few tourists. Every few days there was a revelatory view when the clouds parted or played peak-a-boo with the mountains beyond. Plentiful mud and leeches completed the environment.

There were originally five of us, and we were going to study privately with Munindra-ji. After some days in Kausani a letter arrived from Munindra-ji saying he regretted not being able to come. He had to take care of his mother, who was ill. It was going to be a self-directed retreat.

The house soon proved too small. One day we looked down the hill and saw a group of Westerners getting off the bus. Maharaj-ji kept sending more Westerners to join us, telling them to study meditation with Ram Dass. Maharaj-ji had set me up. Now with about twenty people, we moved to the main hotel in Kausani, the eponymous Gandhi Ashram, where Mahatma Gandhi was briefly sequestered by the British.

Besides meditation and early morning chanting, I began devising exercises to help people lighten their karmic load. I would sit with each individual, and we would look into each other’s eyes. After we had established contact and watched the passing clouds of our mind stuff for a while, I would say, “If there’s anything that makes you uncomfortable, if there’s anything that you feel you can’t tell me—tell me.”

I was trying to re-create the way that Maharaj-ji worked with people’s “stuff.” But he knew everything in people’s heads, and I didn’t. I was aiming for that unconditional love. I was loving people after they had shown me their greatest shame or pain.

Rivers of anxiety, insecurity, suppressed rage, and sexual feelings, secret tales of shame and regret all poured out from people in deepest confidence, all to be released into love. Except, as it turned out, there was an unseen hole in the ceiling. The young woman in the room above could hear everything. Before long everyone knew everyone else’s inmost secrets. There was nowhere to hide. Everyone’s secrets were cosmic gossip. It was just another reminder that Maharaj-ji knew everything.

It was a relief to finish the “meditation retreat” and return to the confines of Maharaj-ji’s temple. When we got back, Maharaj-ji pointed to me and said, “Here comes the Buddhist meditation teacher!” He laughed joyously. Still mortified at having had to give up my studies, I had to laugh too. It was another reminder that there was nothing to learn or do; I could only become it.

Walking about. Many of us had learned Buddhist walking meditation, and though we were by no means formally practicing, our strolls indeed became meditative in the environs of the ashram.

You could also walk overland to the ashram. The distance by taxi or bus on the twisting hill road from the nearby town was some fourteen kilometers, but you could take a more direct route to the ashram by walking on footpaths. You would trek up the hill behind our hotel to a high point called Snowview, where you could see the Himalayan peaks, then walk down footpaths (there were no roads) through valleys and tiny farm villages for a couple of hours before arriving (if you hadn’t made a wrong turn) at the back side of the ashram. It was a journey into another world, simple and pastoral, what the Hobbit Shire might have been like in Tolkien’s mythical world with the added rough edges of hardscrabble farming and Himalayan winters. That excursion from the modern world into timeless village India was a beautiful way to quiet the mind before arriving at the ashram.