ALL BEINGS are on an evolutionary journey, and not just a Darwinian one. There is an evolution of consciousness reaching toward perfection, oneness, and divinity. Hindus and Buddhists believe each individual goes through countless incarnations on this road to fulfillment.

A lot of people ask me, “How do you know about incarnations?” I haven’t experienced my past incarnations, but from being with my guru, Maharaj-ji, who’s farther up the mountain, I have an understanding of how it all works. He would speak of reincarnation as a reality, and I and the other people around him had a very deep relationship with him and each other that clearly had not come from our family backgrounds or upbringing in this life.

Our human forms are composed of and surrounded by an infinite myriad of forms, all in constant motion, from the subatomic to the cosmic in scale. This is the lila, the enchanted dance of existence, the divine interplay of consciousness and energy. Amid this divine play we seek fulfillment, perfection, flow, freedom, enlightenment, Oneness.

The dominant quality of form is change, because all forms are in time. That’s another way of saying we don’t know what will happen from one instant to the next. Or, as one of my guru brothers is fond of saying, “Don’t be surprised to be surprised!” For instance, I didn’t anticipate I’d be living in a wheelchair today. The way to live with change is to be completely present in the moment (remember, Be Here Now).

We cannot cling to forms or our experiences of them, because they decay and dissolve back again into their formless state. Attempting to hold on to anything in time is ultimately futile and a cause of much suffering. What is really there to hold on to? In reality there is nothing permanent, nothing solid, nothing constant except relativity and change themselves.

When we realize how finite are the limits of gratification or possible fulfillment within the play of forms, then despair arises. That despair is born of the world-weary understanding that nothing in form can provide ultimate meaning. It also forces and demands awakening and seeks transcendence of suffering.

If futile clinging to impermanence creates our suffering, letting go and making friends with change is joy, liberation. In youth our lifetime seems to stretch infinitely before us. As we age, the accumulation of our experiences seems to have occurred in the blink of an eye. Even now that I’m seventy-nine years old, I realize there’s plenty of change to come before dying—change in the body, change in friends and family, change in memory. These experiences lead to deepening wisdom and freedom and to diving deep within to the realm beyond form.

Long before recorded history, human beings were awakening out of the illusion of form or separateness that the Indians call maya. A tiny fraction of humanity, but still many beings, finish their work and complete the process of realization, the integration of form and the formless. These awakened beings pass beyond the illusion of birth and death and attachments to this physical plane and every other plane. Their hearts fill with the bliss of that realization and with the infinite love that permeates the universe the way that dark matter permeates the space between stars. That love is the subtle texture of our material world, the unseen energy, the fullness of emptiness (sunyata).

Open your eyes of love, and see Him who pervades this world! Consider it well, and know that this is your own country.

When you meet the true Guru, He will awaken your heart;

He will tell you the secret of love and detachment, and then you will know indeed that He transcends this universe. . . .

There the Eternal Fountain is playing its endless life-streams of birth and death.

They call Him Emptiness who is the Truth of truths, in Whom all truths are stored!

There within Him creation goes forward, which is beyond all philosophy; for philosophy cannot attain to Him:

There is an endless world, O my Brother! and there is the Nameless Being, of whom naught can be said.

Only he knows it who has reached that region: it is other than all that is heard and said.

No form, no body, no length, no breadth is seen there: how can I tell you that which it is?

He comes to the Path of the Infinite on whom the grace of the Lord descends: he is freed from births and deaths who attains to Him.

Kabir says: “It cannot be told by the words of the mouth, it cannot be written on paper:

It is like a dumb person who tastes a sweet thing—how shall it be explained?”

—Kabir1

When they finally emerge from the illusion of separateness, these free beings can either merge back into that formless state or remain in form on one plane or another, or they can continue their evolution to the point where it makes no difference. They may or may not take birth again on the physical plane.

Sainthood

In the East, liberated beings are often referred to as saints. The term has different connotations in different cultures. In the Catholic Church a saint is someone who has been canonized by the church and is confirmed to have performed miracles. In the West, we also use the term metaphorically when we say, “She’s a real saint,” or “That was a saintly thing to do.” We don’t usually mean that they were canonized by the church, but that they are unusually good or loving or particularly self-sacrificing people.

In India someone might be called a saint who is a sattvic individual, someone who is pure and oriented toward the light, a good person connected to the spirit. A saint can also be a liberated being who continues to take birth to relieve the suffering of other beings, what Buddhists call a bodhisattva.

India also has an ancient tradition of yogis and rishis, or forest sages, who were the living sources of spiritual life and knowledge. These great souls, or mahatmas, laid the foundations of India’s spiritual culture thousands of years ago as recorded in the Vedas. Some even entered the social and political arena, like the kings Dhruva and Shiva-ji and more recently Mahatma Gandhi.

There are also holy men and women who act as gurus, spiritual guides, and preceptors, a tradition much attenuated in modern urban society, but one that is still intertwined in Indian culture and persists to this day. Holy men are often called baba, a Hindi term meaning “father” or “grandfather” but used as an honorific, for example, Neem Karoli Baba. Beyond all classification is a rarefied class of great saints or yogis who have reached the pinnacle of consciousness, fully realized beings, the perfected ones, or siddhas. People revere and seek counsel from these great saints and go on pilgrimage to seek them out.

We in the West may lack this ingrained tradition of seeking out holy men and women, though doubtless they are present here too. I have met some: a car mechanic in Boston, a Taos artist, Native American elders, Zen Buddhists, Sufis, artists, chemists, musicians, healers, and poets. Some were wonderful teachers. Most still had karma (the results of past actions, the laws of cause and effect) they were working out. Each had some aspect of the One shining through, and all were beautiful human beings. This is not to say we Westerners are not truth seekers. Yet we are not a traditional culture like that of the Native Americans, whose deep reverence for their spiritual elders is similar to the way holy people are woven into the fabric of spiritual life in India.

This contrast was readily apparent to me when I traveled back and forth from Nainital in the Himalayan foothills to New York City. The people of Nainital, at least some of them, identify with their souls. In that part of India the world is still viewed from the vantage point of the soul. The Himalayan region is different from the plains and has been frequented by yogis and saints for millennia. The people seem simpler, hospitable, and loving, and their traditional culture keeps the stories of realized beings alive. They know they are souls.

Although the cities in India are largely Westernized, in the villages traditional people still realize they’re on a spiritual journey. It’s a long-term view, because they believe in reincarnation. It may take many births for a soul to become one with God, but they know that’s where they’re going. The villages of India have supported the traditions of sadhus, wandering monks and holy men, and of siddhas, realized beings, for millennia.

Jet travel makes the East–West difference more glaring. The minute the plane door opens in New York, it is ego, ego, ego—everyone identifying with their roles. In the West who you are is defined by what you do. The view seen by the ego is bounded by this single incarnation, which ends in death. The fear of death is a very powerful motivator. The soul doesn’t have that fear. If you make that shift of consciousness from the ego level to the soul level, the fear goes away.

Tewari and his granddaughter, Puja. Photo by Rameshwar Das.

I came back home from India and saw my dad and my future stepmother, Phyllis, at their house, and in my new perception they were indeed souls. They were both aging, and my dad had oriented himself toward death. Although he was on the board of trustees of the synagogue, his religious practice consisted solely of outer form, which left him with a lot of inner fear. The calm space I brought from being with Maharaj-ji must have been reassuring. I was in my soul and saw them as souls, which allowed them to begin to see their lives more spaciously. Over the next years there was a deep change in our relationship. We were together as souls.

Years before, we were sitting in deck chairs at my father’s three-hole golf course on the family farm in Franklin, New Hampshire. It was a beautiful sunset, and I said, “Dad, isn’t it beautiful!”

“Yes, look how beautifully it’s cut,” he replied. He had just mowed the grass and was proud of how the greens looked.

When he was about ninety-five and we were living down in Cohasset along the Massachusetts south shore, he was in bed, and I was holding his hand. We were looking out the window, and he said, “Look, Rich, what a beautiful sunset!” That was soul wonder—we had come full circle.

In Nainital people do the dharma of their social role, but at the same time they know their soul is separate from their role. A sweeper isn’t necessarily just a sweeper, the king isn’t necessarily just a king; they are doing their dharma for that incarnation, while the inner being is also there looking out. From that soul point of view, your karma is your dharma, what you do is part of your inner journey, and your role takes you into your soul. Then you get a chance to stand back and see what in your incarnation is helpful to you as a soul and to others on your trip to God.

A Meeting of the Minds, and Heart

In the West it’s hard to even conceive of enlightened beings. We have much to learn about how to approach them, how to be with them, how to use them on our own journey into our heart. Cultures like that of India have customs and forms that, although perhaps not directly transferable, can show us how to be in the presence of a holy person.

As a teenager getting ready for a date, I would go to great lengths dressing, combing my hair, buying flowers, acquiring the money, planning the evening—there seemed to be no end to my preoccupation with the momentous trivia of going on a date. Only when everything was in order could I begin to open to the relationship. If my shoes were scuffed, I would spend a good part of the evening hiding them under an available chair or couch or being embarrassed or self-conscious about them. In its own way opening to the presence of a holy being, a lover for your soul, demands that same kind of psychological preparation.

When I first traveled around India and saw holy beings, I treated these meetings rather casually and just enjoyed being with whomever I happened to be with at whatever level we happened to meet. But as time went on, I began to appreciate receiving the presence of spiritual beings more deeply and having the opportunity to drink from the well of their experience. I came to understand that this transmission of living spirit involves preparation in order to be open to receive it. Slowing my mind down enough to be in the moment in “Indian time” was one part of that. Opening my heart to feel their love was another.

Imagine living in India twenty-five hundred years ago. You hear about an enlightened being walking the earth called Gautama Buddha. You set out to find him to receive his teachings.

Perhaps you go to Sarnath, where he delivered his first sermon in the Deer Park. You talk to the newly ordained bikkhus, or monks, gathered there and ask his whereabouts. They direct you to a town to the north. You travel on foot, in a horse-drawn wagon, or by oxcart. In each village you receive another report, making you feel you are getting closer. Your anticipation mounts day by day as you move from village to village, your mind fixed on the moment when you will meet this being, sit before him, and receive his teaching.

Weeks go by, and you begin to meet people who have just been with the Buddha. Their eyes are alight, their hearts open. They emanate a peace that speaks of the experience they’ve had. Finally you are within a day’s travel of the Buddha. Your mind turns to how you will prepare yourself for this meeting. As you near your destination, you stop and bathe and wash your clothes, perhaps pick some flowers or fruit in one of the villages. As you get very close, you are so excited you are afraid that you will not be quiet enough to receive him. So you sit on a rock by a stream, collecting yourself.

Finally you approach the cave where the Buddha sits. You climb the hill to the door of the cave. It is dark inside. A small fire flickers, and in the firelight you see someone sitting in meditation. After some time, he becomes aware of your presence and motions you to enter. You enter, bow before him, and offer your fruit and flowers. You sit before him and finally raise your eyes to look into his. Time stops. Everything you have been anticipating is coming to fruition in this moment.

The universe disappears. Only his eyes exist. A flow of love, wisdom, consciousness passes between you. Perhaps a few words are said—words you take away and think upon again and again in the years to follow. Or perhaps he says nothing, and it is just his stillness, his presence, the incredible love that flows from him, the deep compassion you feel. You feel as if you were naked before his glance. He sees through you, he knows all—past, present, and future. He does not judge, but simply acknowledges how it all is. Even a moment of such compassion can be liberating.

Road Signs and Map Readers

There are no maps for this journey, but it’s helpful to have some understanding of what realization or awakening is really about. In truth, the Great Way resonates in the heart for each of us. We each have our path. There are many routes up the mountain, but they all end at the peak. The grace and forbearing love of the great ones are there to guide our steps, if only we know to look for them.

O brother, my heart yearns for that true guru, who fills the cup of true love, and drinks of it himself, and offers it then to me.

He removes the veil from the eyes, and gives the true Vision of Brahma:

He reveals the worlds in Him, and makes me to hear the Unstruck Music:

He shows joy and sorrow to be one:

He fills all utterance with love.

Kabir says: “Verily he has no fear, who has such a guru to lead him to the shelter of safety!”

—Kabir2

Of course, things never happen as you expect. My primary motivation for being in India the first time was to find someone who could read the maps of consciousness that had unfolded for me when I first took psilocybin mushrooms on March 6, 1961. The maps of Western psychology were of no use with psychedelics. Those planes of consciousness were not explained by psychology. The Tibetan Book of the Dead was the best depiction I had up to that point.

I was convinced of that by an LSD trip I had on a Saturday night that was so completely ineffable I couldn’t even talk about it. The next Tuesday I first saw the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which was given to us by Aldous Huxley. It was the old Evans-Wentz translation, and it led Tim Leary to meet with Evans-Wentz. In it I found an uncanny description of my LSD trip, and that was how our book, The Psychedelic Experience, came into being. We used the Tibetan bardo (the disembodied astral state between births) as a model for psychedelic trips. That was the “map” that inspired me to go to India.

My goal in India was to find someone who could read the maps of consciousness. But as I reflect back on the mind-blowing day I met Maharaj-ji, I thought I was merely a passenger in the car. My traveling companion, Bhagavan Das, said he needed to go see his guru about his visa. I had a Land Rover that my friend David Padwa had allowed me to use. I was responsible for it, and Bhagavan Das talked me into letting him drive it up to the mountains to see this guru. He knew I didn’t like Hindus because of all the calendar gods and statues and the loudspeakers at the temples. My anal-compulsive personality was more attracted to Buddhism.

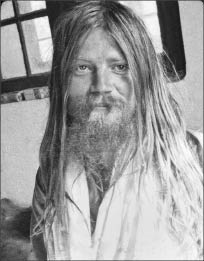

Bhagavan Das. Photo by Ram Dass.

As we headed up into the Himalayas, we spent the night at a house near Bareilly somewhere out in the country. In the middle of the night I had to go to the bathroom, which was an outhouse. The stars seemed very big and the heavens close. I thought of my mother, who had died about six months previously. She seemed very close too. I had to laugh at myself, because here I was, a Freudian, thinking about my mother on the way to the outhouse. Then I went back to bed. The next morning we continued another fifty miles or so, winding up the switchbacks into the Kumaon region, in the foothills of the Himalayas.

We finally arrived at a little roadside temple at a place called Bhumiadhar. A crowd surrounded the Land Rover. They were very warm toward Bhagavan Das, who spoke Hindi and was conversing easily with them. All I could do was listen. He told me, “They say my guru is up on the hill. So, if you don’t mind, I’ll go up there.” He was so moved about seeing his guru that he was crying, and he loped up the hill. I stayed in the car. I was feeling tired and frustrated and eager to go back to America. I didn’t know how long he was going to be gone. He didn’t invite me to come because he knew I didn’t like gurus.

I had no idea what was going on. There I was in this big fancy car. After he got out, I thought the crowd turned hostile toward me. I was very paranoid. I didn’t speak Hindi, and I wasn’t rushing up to see any guru. The people around the car were insistent that I go see him. They were yelling at me, because I wasn’t following my friend up the hill to meet Maharaj-ji. Of course, they wanted me to have a chance to meet a saint, but I thought they wanted me to get out, so they could get the Land Rover. That’s how paranoid I was. But finally my curiosity got the better of me, and I got out of the car and followed Bhagavan Das up the hill. But I kept looking back at the Land Rover, worrying that people were going to steal it.

Up on the hill a man in a blanket was sitting on the grass with ten or twelve people around him. I kept my distance. Maharaj-ji pointed to me and said something in Hindi. Someone was translating for me, who I later learned was K. K. Sah. The first thing Maharaj-ji asked me was “Did you come in a big car?” The next thing he said was “Will you give it to me?”

That immediately set off all my paranoia about gurus and made me angry. Bhagavan Das was flat on the ground in dunda pranam, a posture of deepest respect. He leaped to his feet and said, “Maharaj-ji, if you want it, you can have it.”

That really fueled my paranoia, and my anger almost boiled over. Besides that, the Indians grouped around were all laughing at me. Of course, they knew Maharaj-ji would never ask for a car, but I didn’t know that. He was playing with me like a cat with a mouse. I had no idea who he was or how he operated. Years later K.K. described me standing hunched with my hands in the pockets of my jeans looking angry and afraid. I just remember feeling very uptight. K.K. thought I was completely stuck in my ego. He was right.

What followed was the kind of opening that can only be performed by a true guru who knows the precise moment when the nut is ripe to be cracked open with a single sharp tap. Maharaj-ji began telling me things about my previous night under the stars and my mother’s recent death that he couldn’t possibly know. Then he said, “Spleen!” in plain English, which is what she died of, cancer of the spleen, and my unreleased emotions cascaded with the impossible fact that this baba in the Himalayas knew every detail about my mother. Something in me shattered, and I just began to sob. I was flooded with grief, and relief, and the immensity of traveling halfway around the world to find this loving old man in a blanket who knew. Still dazed and confused, I was sent to stay at K.K.’s house in Nainital that night. Maharaj-ji told him to feed me toast.

Becoming a Yogi: A Six-Month Short Course in Renunciation

From that first meeting with Maharaj-ji, I was totally in the moment. It was almost inconceivable that I was surrendering to him and that he was taking me over; it just didn’t compute. I wasn’t time binding; I wasn’t relating it to the past. Maharaj-ji did that to me. His love made it okay.

I was planning to say good-bye to Bhagavan Das and go back to the States in two days. Instead, I found myself staying in an ashram in the Himalayas for six months, which seemed like Maharaj-ji’s plan from the beginning. What always surprises me is that I had no resistance. Earlier that day I was so paranoid about the Land Rover and so averse to meeting a guru. Yet immediately afterward, I was perfectly willing to go and stay at K. K. Sah’s on Maharaj-ji’s instruction. It was like home to me.

That was a momentous shift. I still don’t have words to define it, but it was a complete figure-ground shift in my perceptual vantage point. I went from being an assertive, decisive person to completely surrendering and allowing Maharaj-ji to run my life. And I didn’t even think about it; I just shifted. I wasn’t self-conscious about it; it just felt completely natural. I was suddenly on a completely different life path, and I hadn’t made any kind of a conscious decision. The day before, Maharaj-ji and Hinduism had been anathema. But now they had just taken me over, and I felt as if I were home. That’s the power of Maharaj-ji’s love.

Because I had taken so many LSD trips, I was used to changing my consciousness in big leaps. Acid got me ready for Maharaj-ji. If it wasn’t for that, I never would have stopped long enough. I wouldn’t have had the curiosity to open the door of the Land Rover. Before that, I was so busy making decisions about Bhagavan Das and all that melodrama. We were walking around Sarnath from temple to temple barefooted. It was hot and uncomfortable, and I had blisters. The Hindus were treating us like sadhus, wandering holy men. Poor pilgrims were leaving rupees in front of me as offerings. Meanwhile, I had traveler’s checks in my pocket.

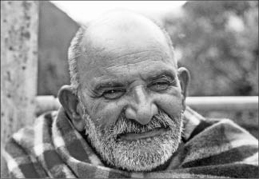

Maharaj-ji. Photo by Balaram Das.

After that first meeting, when Maharaj-ji sent me to stay with K. K. Sah and his family, they were so gentle and kind to me. Here I was, an unknown foreigner disrupting their lives, and they just took me in. They treated me like a member of Maharaj-ji’s family. K.K. is very much an instrument of Maharaj-ji. Maybe Maharaj-ji saw it all in advance, the role K.K. was going to play with the Westerners. After a day or two with K.K.’s family I saw Maharaj-ji again at Bhumiadhar. Then he sent me to the ashram at Kainchi to begin my sadhana, the inner work, including yoga with Hari Dass.

Darshan: A Point of View

In India there are simple rituals to prepare for darshan, to visit a saint, guru, or siddha. When you enter the temple, you pay your respects to the deities, which begins to open you to that heart space. You offer obeisance, or pranams, fruit or flowers, sweets or money to a holy person and touch their feet. It’s not really giving or receiving on the material plane, but more like opening yourself to more spiritual energy, or shakti. Later as my heart opened, I came to appreciate how these simple ritual acts enriched my experience.

Of course, when I first met Maharaj-ji, I didn’t do any of those rituals and it didn’t matter. The real saints are beyond rituals, and gurus or siddhas are often unorthodox. They may acknowledge you or ignore you, send you away or feed you, maybe allow you to share their presence and enjoy their darshan for some moments or hours.

Darshan literally means “a view,” sharing another’s vantage point, a point of view that comes from that higher place of the spirit manifested through another being. It’s a profound shift from the point of view of the ego to the point of view of the soul. It can make all your study and reading come to life in a moment. It can be an experience so profound as to change the direction of your life, return you to your spiritual roots, take you beyond all words and thoughts into the most profound depth of the heart. In that depth, the little soul begins to dissolve into the bigger Soul. That movement from the individual soul, the jivatman, to the greater soul, the ![]() tman, is like dissolving into the ocean of love.

tman, is like dissolving into the ocean of love.

Although I was with Maharaj-ji in India, you don’t need to sit in a saint’s physical presence to have his or her darshan. Darshan can occur in a dream, through a picture, a statue, or a physical place or from hearing the voice or reading the words of a realized being. The true nature of darshan is not the meeting on the physical plane; it is the meeting on the soul plane. It is not words or pictures, pilgrimages or teachings. It is not the stuff of our senses or our thoughts. Darshan is the meeting of hearts, the merging of souls, sharing the moment with complete awareness, compassion, love, and energy.

Through words and pictures, we speak to one another about the unspeakable. We look to see the unseeable. We try to understand the unknowable. And all the time this process is going on—all that yearning, trying, listening, looking, thinking—on another level the moment is complete unto itself. In that complete moment the transmission, the transmitter, and the receiver of the transmission are one. It is a moment of pure love.

For the devotee, darshan extends far beyond the physical presence. Thinking about a saint, looking at a picture, remembering precious moments, recounting stories with other devotees all continue the darshan. Devotees are like bees drawn to flowers to make more honey. Devotees make darshan their focus, the way a compass needle points to magnetic north.

Around Nainital, in the foothills of the Himalayas, there is a long tradition of saints who have inhabited the area, and each family has its share of stories. We would often sit around the fire in the kitchen drinking chai, exchanging the intimate stories, the incidents of daily life with the beings that one or another of us had contact with. Individuals might be known for the way they recount a certain incident. As the stories are told again and again, they keep taking on new richness, enhancing the depth of the love. These incidents are not just stories or folklore, but the fabric of spiritual life and the foundation of faith. It’s bliss to hear these stories, the lilas of the saints, described by the old devotees there. They make them come alive.

He is like a flower turned into a nose to smell its fragrance, or a face enjoying the knowledge of its own identity which was already in existence but was due to its looking into a mirror. So the master and his disciple appear as two, the master alone enjoys himself under the guise of the two.

—Jnaneshwar3

We would sit by the fire, Indian and Western devotees gathered together, sharing these loving stories of the saints. At the end someone would say, “But who can understand such beings?” Our minds could not expand enough to truly comprehend their consciousness, compassion, and wisdom. But these stories continue to take on meaning. Even the simplest acts of such beings reverberate on many planes through time.

We used to talk and talk. Bina, K.K.’s sister, would come in and ask if we would like tea again, thinking we would say no because we had had tea already. But we said yes, and she had to go and start up the wood fire again, because there was no gas stove, as there is now. No one wanted to stop. The joy of that kind of devotion is hard to imagine for someone who has not been in that family atmosphere.

When I sat in the kitchens of that Himalayan town, at first I was only interested in stories about my own guru, Neem Karoli Baba. The other stories were of saints long gone from their bodies. But slowly I began to appreciate the profound teaching that came through each recollection. I began to listen for that kernel of light, the jewel of spiritual teaching in each incident, each commonplace miracle in the lives of these great beings. These gatherings are satsang, the community of seekers—a spiritual family that recognizes truth and shares the bhava, the mood, of devotion.

There are thousands of saints in India’s history. A few like Sri Ramakrishna, Ramana Maharshi, and Shirdi Sai Baba are well known; books have been written about them. Some had thousands of devotees, and temples were built in their honor. Others are remembered through the poems and songs of God that poured forth from them, making up the folklore and music of India. So many others, local saints and jungle sadhus, yogis living in mountain caves or known only in a few villages, are no less pure, but their dharma didn’t involve public recognition. Some are secretive or even intentionally put people off, like one baba who used to throw feces at passersby. Many of the most remarkable stories are about these beings.

Some of these stories tell of astonishing miracles far beyond the powers we attribute to human beings. Others are just about the daily trivia of life, each event reflecting in some way the living truth that comes through someone who is at One. Every act of a realized being is a teaching. The way they wash a dish conveys the wisdom of the ages. The way they walk down the street, the movement of a hand, a facial expression—it’s all pure grace. A being who has merged with love, merged with truth, is grace itself. How many may walk among us we will never know.

Liberation

When I speak of a liberated being, I mean someone who is free from entrapment in any one plane of consciousness or relative reality. A rocket that can get out of the earth’s orbit would be liberated from the pull of gravity. Each reality has its own gravitational field of desires and belief systems. A person who is liberated from this physical/psychological plane is someone who can break the identification with that which is born and dies, that which desires birth and believes in death.

Most of us are very attached to this physical plane of existence, and to become free of it, to enter into another plane, is in a sense liberation. However, you can be entrapped on other planes even though free of this plane, which is far from total perfection. The ability to get out is different from the ability to come back in, to integrate the planes. When someone breaks out of the earthly plane’s psychic gravity, they may be so blown away by the presence of God that they don’t want to come back. Sometimes they become what in India are called masts, the God-intoxicated, who may seem psychotic or disoriented, because they haven’t reintegrated on the physical plane. Slowly they learn how to go in and out, to the extent there is still any inside or outside.

Some seekers may become so transfixed by the delights of astral planes that they linger there. There are many saints who are almost perfected, who work on one plane or another, but some of them have not dealt with the final stages. This doesn’t mean they’re not great teachers or saints, only that they haven’t yet finished their work.

Perfected beings, or siddhas, hold to nothing, stand nowhere, and can go in and out of all planes. They do not really go in and out of planes, because they are in all planes simultaneously. Such beings are no longer bound by time and space and may manifest or not, keep a body or drop it. In that fluid state all is possible—to keep the body young or to leave it, to merge into God or stay in form for the liberation of all beings. Such beings are beyond all law and limitation. They are the dharma, the perfect harmony of God’s will and the human mind. Every plane is flowing into every other plane, and God is flowing through them as instruments. It’s just unbroken flow. Then it’s nothing special, no difference, all One.

At this point it’s not about the experience but about the experiencer. As the planes start to come together, you go to a place where you die as the experiencer into the experience. It doesn’t have anything to do with you. It just is, and you’re not doing it. Many beings have never taken that step, that immolation or dissolution of the individual. The separate self is alone, while the true Self is Unity, becoming One, the end of identifying as a separate being. (As in the joke, “What does the Buddhist say to the hot dog vendor?” “Make me One with Everything.”)

The paradox of the One is that when the ego dissolves, there’s an experience but no experiencer. The experience happens, but you the experiencer are different, you’ve gone beyond that small self. The outward experience may be the same. As Zen Buddhists say, “Before satori (enlightenment) you chop wood and carry water. After satori you chop wood and carry water.” It’s one of those “tree falling in the forest” things. But there’s also the existential reality of that state, being in a physical body and at the same time in the void, the Absolute. The ultimate place is to be in form and not in form simultaneously, one foot in the world and one foot in the void, a physical reality completely continuous with perfect luminous emptiness. Emptiness is not an experience. Here words fall short. These are two different places of consciousness; human beings can function on two planes at once.

Nobody hOMe

The question of whether a being is fully realized or not depends on whether that being is really egoless or just appears to be so. If a person still identifies with thought forms or desires, the work is not complete. In perfection there’s no clinging at all.

Perhaps now you begin to see the subtlety of the attachments that must be surrendered. The attachment to experiences, including the experience of God and the ecstasy and rapture of that union, even experiences of omniscience, of omnipresence, of infinite power, the experience of being the One (as opposed to just being One)—these are described in southern Buddhism as jhanas, or temporal absorption states. As long as there’s a trace of an experiencer, there is still an element of self-consciousness, the ego of being the experiencer. If it’s still an experience, it is not the ultimate reality. It’s simple: if you’re having an experience, you know you have to go beyond it. Isn’t it beautiful?

The mind is a bundle of thoughts. The thoughts arise because there is the thinker. The thinker is the ego. The ego, if sought, will automatically vanish.

Reality is simply the loss of the ego. Destroy the ego by seeking its identity. Because ego is no entity it will automatically vanish and reality will shine forth by itself. This is the direct method, whereas all other methods are done, only retaining the ego.

—Ramana Maharshi4

For a perfect being, a Buddha, there’s nobody home. They are completely here and nowhere and everywhere at once. A perfected being is fully in the flow of existence, so there’s no place where they’re not. The paradox of emptiness (sunyata) is that it is really fullness. Egolessness is not nonexistence, but an effulgence of being. Finally there is just function at every level. That’s what Christ referred to when he said, “Had you but faith, you could move mountains.”

I used to feel I was at the edge of a beautiful calm lake with the earth under my feet, and I would want to jump in, but I didn’t have the courage. It was like trying to do a back dive when I was a kid. I would stand in position on the diving board for perhaps an hour, and I would know it would all be good, but I just couldn’t do it.

Love is what lets you dive into the emptiness behind form. The jump from things to no-thing, to emptiness, just means it’s empty of experience. It’s like two planes: one is the plane of the soul; then you leave that behind and dissolve into the One, which is emptiness. You let love carry you into merging with the One. It’s the devotion, bhakti, that takes you through to the wisdom, or jnana, the satori of Zen.

Love is what’s melding the universe together. You love everybody and everything more and more until you love all things in the universe, and you identify with all things and become the One. When you dive into the One, you find emptiness, because there’s no experiencer in the One. The love brings about that melding, that jump from being everything to being nothing, from being somebody to being nobody.

With Maharaj-ji there was nobody there; there was just love. I used to see him turn into a mountain, like Shiva, the pure absolute, but then I would feel this intense love. He is unconditional love, but it’s impersonal. It wasn’t him loving me; it was him being love. I turned it into something interpersonal, but it wasn’t.

Love is the emotional color of the soul. Unconditional love is the color of enlightenment, unfettered by personal barriers or distinctions, devoid of ego, yet reflecting the highest Self. It’s like sunlight unfiltered by clouds or the taste of water from the purest spring.

If thou desirest to be a Yogi,

Renounce the world.

Dye thy heart deep in His Love.

For real lovers drink the cup of Nothingness, and

Pass away into the Valley of Amazement, in remembrance of Him.

—Shah Latif (1689–1752)5

We can learn unconditional love from those who live in it, the saints and siddhas, from their darshan, their presence, their satsang. We may get a taste of it in an Indian family, absorbing the traditions and customs, the affection between grandparents and grandchildren. In any case, to feel it, we have to let go of our analytical minds and open ourselves to the moment and to those who have gone before.