MY RELATIONSHIP WITH MAHARAJ-JI is one of faith, faith that what comes to me from him is grace. When I have faith, I feel grace coming from the guru. If I have faith, then there is no event in my life and no place where that grace isn’t.

When I live in faith that I am under his umbrella, then there’s no fear. He gives whatever is needed to deal with whatever comes along. Without faith, the existential fears that we all have dominate. Faith, no fear. No faith, fear.

When I had the stroke in 1997, a lot of suffering came with it. A stroke isn’t something you plan for, and it was a surprise. In the first days after the stroke I couldn’t feel Maharaj-ji. I asked him, “Were you out to lunch?” I really lost faith, which put me into a depression. I had to learn how to ask for faith again at that time. The Brazilian healer John of God, whom I talked about earlier, helped heal my heart. As I began to recover my faith, I accepted the stroke as the hand that Maharaj-ji had dealt me, and I began to call the stroke “fierce grace.”

But when Siddhi Ma, the Mother in India who maintains Maharaj-ji’s scene, saw Mickey Lemle’s documentary about this time, called Fierce Grace, she sent me a message that Maharaj-ji would never give me a stroke. I took that in and realized finally that his grace was not the stroke, which was my own karma. His grace lay in helping me deal with the effects of the stroke, which included paralysis, aphasia, and dependence on others. Dealing with the suffering from the stroke in my mind changed my life. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody, but it had its positive side. And over time it has tempered and deepened my faith.

A disciple, having firm faith in the infinite power of his Guru, walked over a river even by pronouncing his name. The Guru, seeing this, thought within himself, “Well, is there such a power even in my name? Then, I must be very great and powerful, no doubt!” The next day he also tried to walk over the river pronouncing “I, I, I,” but no sooner had he stepped into the waters than he sank and drowned. Faith can achieve miracles while vanity or egoism is the death of man.

—Sri Ramakrishna1

A few years after the stroke I wrote to K.K. saying I didn’t think it would be possible for me to return to India. K.K. wrote back with some simple words that Maharaj-ji had said to him about me: “I will do something for him.” Like Hanuman, he thought I needed to be reminded of the power of my faith so I could get it together. As I recollect and reconnect to him, I realize Maharaj-ji has done, has been doing, is doing something for me. I did go back to India in 2004 and I experienced a resurgence of the deep faith I have in him, in that Oneness in which we exist together. Just that remembrance deepens my faith.

His presence helped me see it as a “passing show” of body phenomena, while my soul remains enveloped in his love. I’m quieter now inside, and I’ve learned from my own silence, which increased when I couldn’t talk after the stroke. From being the driver of my own car I became a passenger in a body that now needs help from others. From someone who had written a book called How Can I Help? with Paul Gorman, now I needed to write one called How Can You Help Me? It’s been deeply humbling for my ego.

As I questioned my own faith, I began to ask, “Faith in what?” I found that my faith is in the One, not faith in a person, but in the One. Faith is a way in which you are connected to the universal truth. Faith and love are intimately connected. As it says in the Ramayana, without devotion there is no faith; without faith there is no devotion. In a way it’s the guru’s own incredible relation to God that’s the transmission of living faith, the fact that he or she is living in the light of God. That connection is love.

A book doesn’t give a living transmission. It’s the light coming through the guru, the remover of darkness. Faith really comes from within you, and the guru is awakening it. Faith comes through grace. You can cultivate it by opening your spiritual heart and quieting your mind until you feel the validity of your identity with your deeper Self. The qualities of that Self are peace, joy, compassion, wisdom, and love.

Faith is not a belief. Faith is what is left when your beliefs have all been blown to hell. Faith is in the heart, while beliefs are in the head. Experiences, even spiritual experiences, come and go. As long as you base your faith on experience, your faith is going to be constantly flickering, because your experiences keep changing. The moment you recognize that faith lies behind experience, that it’s just being, not the experience of being but just being, then it’s just “Ah, so.”

For the unified mind in accord with the way

All self-centered striving ceases.

Doubts and irresolutions vanish

And life in true faith is possible.

With a single stroke we are

Freed from bondage;

Nothing clings to us and we hold to nothing.

All is empty, clear, self-illuminating,

With no exertion of the mind’s power.

Here thought, feeling, knowledge, and imagination

Are of no value.

In this world of suchness

There is neither self nor other-than-self.

—Seng-ts’an, Third Patriarch of Zen2

Working Guru

The guru intensifies experiences. Right there in your consciousness all the time is this being who is completely free, loving you totally and with the deepest compassion for your situation. The absurdity of your attachments in relation to this incredibly wonderful being drives you to deal with your petty stuff and to get it out of the way. In a sense the guru uses your attachment to daily situations to show you your own delusional system.

The guru is constantly showing you where you’re not, your most secret places where you’re holding on to your stash of attachments. For people who are still intensely attached to their senses and to their thinking minds, the guru manifests the teachings on the physical plane. The true guru is also beyond form, even though he or she may take on a body in order to do this work.

As the intimacy between you and your guru increases, the desire to merge intensifies too. It’s a bit like going downhill on a runaway train. There’s a point where the velocity becomes so great you can no longer jump off without it being fatal (to the ego), and at the same moment you realize the ride itself may be fatal too.

I experience it as if my body is in big surf, being buffeted and mashed into pulp on rocks and coral by the force of the ocean. When you’re in the surf you can feel its power. You’re in the power of the ocean and you just get pummeled again and again until you practically become part of the foam. You just dissolve into the ocean. It’s just this oceanic process, and every part of you that’s separate just gets beaten and pulverized until it becomes part of the ocean.

There are moments when you come up for air, but that only makes you more desperate. There’s a maximum rate at which you can go in spiritual work without breaking. If you try too hard or get pushed too hard, you get tossed out and land on the beach. And then you may be stuck, sort of rotting in the sand, until the next big tide comes, picks you up again, and takes you back out to pulverize you some more. The tide, and the ocean, is God—it’s the Ocean of Bliss! Pain and pleasure come together at that point, because it can be painful, but the bliss of getting free is very great too. We’re used to pain not being productive, but when it’s that blissful, it’s delicious.

You’re giving up stuff that is so connected to the root of your worldly identity that it’s like a death. You go through some of the same things people go through when they are physically dying—denial, anger, resentment—“Why is it happening to me?” or “Can I bargain my way out of it?” First come depression and despair, then surrendering to the situation, and finally the lightness of a new state of being.

The image of the ocean and the rocks is one way of thinking about it. Fire is a good metaphor too. You are in the fire knowing the only part of you that won’t be burned by this fire is the part that is in God. Everything else will go. You realize how much you are attached to everything, your thoughts, your senses—those have to go too. Remember that mantra? I am a point of sacrificial fire, held within the fiery will of God.

At first I kept a diary of my experiences at Kainchi, but after a while I stopped making entries. What do you do with these experiences? Do you just collect them, file them, and plug them into your model, your same old worldview? Or do you work with each experience, squeezing it like a lemon, and then discard it and let it go? If you keep letting go, then you notice it’s all new every moment.

When Balaram Das, one of the Westerners with Maharaj-ji, used to be sent away by Maharaj-ji, he’d walk around the back of the temple and come in the other door. Each time Maharaj-ji treated him as if he was just coming in. I thought, “Maharaj-ji’s being conned!” But it was also a beautiful example of letting go, letting go and starting fresh.

Balaram is a good teaching in that sense. I wish I had his total one-pointed chutzpah. I am too smart for my own good. I’m too clever, not simple enough. He’s simple in his devotion, in his love, in the intensity of his desire. That can get you a long way, that kind of devotion.

Everything a guru does in relation to other souls is part of that process of liberation. You might not even notice a guru in the street, unless it is helpful to your spiritual growth. Even when you’re sitting in the back row or seeming to be ignored, that is the optimum thing for you at that moment. The full consciousness of the guru is with you from the moment you turn to him or her.

Maharaj-ji.

You crave to be in as pure a relationship to the guru as the guru is to God. There’s a moment, like an initiation or an opening, when the guru shows you who they are. Maharaj-ji opens his eyes, and in an instant you see the universe. Then he closes his eyes, and you’re back. Or Krishna showing Arjuna his universal form. It’s like taking acid. As Maharaj-ji said of LSD, “It allows you to have the darshan of Christ.” It’s that first thing that compelled all of us to go on. But then you have to come back, do your work, and go become it. The only way you can get that purity is to let go of your impurities. It’s a two-stage thing: first the guru shows you who he or she is (really, who you are reflected in the guru), and then the guru sends you back to finish your work.

Guru’s Grease: The Path of Grace

You can’t integrate the guru in your mind. You can’t understand a perfected being; you can only use that being for your own perfection and, eventually, become that place, that state of consciousness, yourself. If you want to come to God, the guru becomes the perfect instrument for getting you there. Gurus have no other motivation. That’s the only reason they are even in our field of view. That’s the only reason any of us are graced to have relationships with these beings. How fast, how consistently, and how totally we use them depends on the intensity of our desire to come to God.

The way these beings help us is to accelerate our journey back to God. That’s the quality of grace, or guru kripa. If you’re aimed away from God, they won’t interfere, but the moment your despair is great enough and you turn toward God, they are called forth by your prayer, by your cry for help, by your seeking for God. Then they shower upon you the grace of their presence and their love, and that higher vibratory rate speeds up your journey incredibly.

Grace lubricates your way, smoothes it out and makes it easy, speeds it up. It’s like having ball bearings instead of wagon wheels. It’s like having the wind fill your sails or walking downhill. It’s like perfumed air, the subtle smell of spring. Obstacles are reduced to a manageable scale. The way to God is grace-full. Grace has humor too, making things lighter, so we don’t take them so seriously. You’re aware of the spiritual meaning and perspective on your life, but it’s a light touch; it’s not heavy. Grace makes it lighthearted, the heart full of light.

For by grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God: not of works, lest any man should boast.

—St. Paul, Ephesians 2:8

This process of thousands and thousands of incarnations now becomes a geometric curve under the intense light, love, and compassion of this grace. The guru doesn’t go against the will of God, but since the will of God has no time in it, since God is beyond time, the guru can speed up the process.

A being like that is only in form for other people. There is no desire in him. That’s why he is such a pure mirror. He keeps showing you where you’re not.

Karma or Grace?

People are drawn to a guru by their own good karma, the result of past actions, the laws of cause and effect. As I sat in the temple with Maharaj-ji day after day, experiencing the incredible grace of his presence, I would think and talk with my guru brothers and sisters about our good karma to be in such a situation. These discussions led to some confusion, for grace seemed to be something freely bestowed at the whim of a higher being. Karma seemed to be something irrevocably bound up with the laws of cause and effect, and it was hard for me to understand how these two things went together.

If Maharaj-ji’s presence was my good karma, it was lawfully demanded, including the way in which he was manifesting. Where, then, was the space for the free play of grace? If, on the other hand, this was the grace of God, bestowed freely outside law, how could one understand the cause-and-effect nature of karma over time?

And he said unto me, My grace is sufficient for thee: for my strength is made perfect in weakness. Most gladly therefore will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may rest upon me.

—St. Paul, Corinthians 12:9

So at one of the group afternoon darshans sitting before Maharaj-ji, I asked him, “Aren’t karma and grace the same thing?”

Maharaj-ji’s answer through a translator was, “This is a matter that cannot be discussed in public.”

He never said anything more about it, although later he sent a message through Dada, “Ram Dass understands me perfectly.” I’m still working on it.

For a long time, I concluded that I had been right—that karma and grace are the same thing. Later I came to appreciate that it was my karma to reach out for teachings, but it was Maharaj-ji’s oceanic compassion that opened my path, through a grace that was indeed free of karmic law. The guru’s grace is beyond the realm of karma, but grace is not necessarily part of everyone’s karma. Maharaj-ji’s grace is a constant flow, whether or not we are aware of it. He said, “You may forget me but I never forget you.”

When asked how to get enlightenment, Maharaj-ji said, “Bring your mind to one point, and wait for grace.” Bringing the mind to one point entails working through the thought forms that are the result of karma. The end of karma is a quiet mind completely concentrated on God, and what takes you beyond that is truly grace. At that point, where the reaching up toward God meets the rain of grace, they’re both the same.

Maharaj-ji. Photo by Balaram Das.

At the level of the nondual, in the One, they are the same. But between the devotee and God, as long as there’s separation, you need to make an effort to get to one-pointedness and wait for grace. At the level of karma, or action, there’s something to do. For the devotee it’s not productive to sit around waiting for it to happen. From where we sit, karma and grace are not the same thing, although from the unitary consciousness where Maharaj-ji sits they are the same. Siddhi Ma said, “From the place of Oneness (sub ek) it is true that karma and grace are one. But it’s best for the devotee to act as if they are separate to do the spiritual work.” For Maharaj-ji there’s nothing to do. He always said, “God does everything.” Things just happened gracefully around him. The simple focus of attention by a siddha, a mere thought, brings things into being. Grace remains free, a river of blessing.

My understanding of this keeps evolving. That’s how a teaching keeps feeding you until finally it clicks into place and ceases to exist as a teaching at all. It becomes part of your being. Maharaj-ji functions within the laws of karma, except when he doesn’t.

One day Maharaj-ji asked to be driven from the plains to the distant mountain town of Bhimtal. He went straight to a devotee’s house and told the people there to go to the old pilgrims’ rest house at the Shiva temple and bring back whoever was staying there. For centuries no one had stayed in the dilapidated rest house, so the devotees thought it was very unusual when they found one of the doors locked from within. They knocked and shouted, but no one answered. Then they returned and reported to Maharaj-ji.

Maharaj-ji left the house and went to see another devotee. He again sent people to the rest house with instructions not to return without its occupants. They caused a great commotion at the door, until finally an old man opened the window. He tried to send them away, but they persisted, until finally he and his wife were taken to Maharaj-ji.

Immediately Maharaj-ji started shouting, “Do you think you can threaten God by starving yourselves? He won’t let his devotees die so easily. Take prasad!” He called for puris and sweets, but the man refused them. Maharaj-ji insisted, until finally they ate.

The couple had come from South India on a pilgrimage to Badrinath and other holy places. Coming from a very rich family, they’d decided to leave home and family behind to devote their remaining years to prayer. They had resolved to always pay their own way and never beg. As they were returning from Badrinath, all their money and possessions had been stolen. They had only enough money for bus fare to Bhimtal, where they found the rest house deserted.

They resolved to stay there and die, since that seemed to be God’s will. They had been locked inside without food for three days before Maharaj-ji forced them out.

Maharaj-ji insisted that they accept money for their trip back to Madras. They said that they would not beg. But Maharaj-ji said that they were not begging, and they could mail the repayment when they reached home. They accepted the money and were sent off.

The Perfect Mirror

The guru is an example of what’s possible for us as human beings. You experience a peace around the guru that’s his or her vibrational field. It shows you a possibility, creates a yearning in you to be in the space that the guru’s in. As you look into a still pool and see your reflection, so the guru reflects back to you your soul and its karma. If there are no desires clouding your view, you see the pure reflection of your soul.

Everyone is a reflection of my face.

—Maharaj-ji

A free being can be a perfect mirror for you, because he or she is not attached to being anybody or to any particular reality. A person who has no clinging is an exquisite mirror, and the beauty of a mirror is that the moment you change, the mirror changes too. It doesn’t reach out and demand you stay who you were a minute ago.

When you let go of any models of how you think the universe is supposed to be, you can see the true reality. You see the guru is none other than God, none other than your Self, none other than Truth.

Looking into that mirror of the soul allows you to see the way you’re creating the universe and helps you perceive your own attachments. When you’re around somebody who doesn’t want anything, your own desires start to stick out like a sore thumb. It allows you to grow and to see where you’re not. You begin to see how your desire system keeps creating your reality.

None of us knew Maharaj-ji; we just knew our own projections. But the relation with the guru is not totally our projection, nor is it entirely created for us by the guru. It’s an interaction in the circumstances of the moment. Your needs as a soul determine the form of manifestation of the guru. Of course, how the guru manifests may not agree with your values or concept of a guru.

Maharaj-ji was fat. His great belly contradicted my idea that conscious people are thin and ascetic. And the foods he favored were so counter to my ideas of what constituted nutritious food. The basic diet at Kainchi was puris, potatoes, and sweets: fat, starch, and sugar. But it didn’t matter, because it was all blessed food; it was prasad. Then when I heard that Maharaj-ji steered away from important politicians and wealthy people, it knocked the whole value system that I’d grown up with for a loop. He was the exact opposite of my father, who always cultivated wealthy and important people.

The saint is a mirror, everybody can look into it; it is our face that is distorted, not the mirror.

—Paltu Sahib3

A guru is perceived differently by all the beings around him, depending on their karmic predicament. One person may have known Maharaj-ji in a deep meditative space, another as somebody who got upset about potatoes that were allowed to rot. If you got ten people talking about him, everyone would describe Maharaj-ji in a different way.

It’s like the blind men and the elephant. One touches the tail, one the leg, another the side, and another the trunk. They can’t agree what the thing is. One blind man says, “An elephant is very like a tree,” another says, “No, he’s like a snake,” and another says, “No, he’s like a wall.” And they get into a fight, because each of them has touched a different part of the elephant. Each person is describing what he has touched, and each touches what he is capable of reaching, but no one gets the whole thing. Maharaj-ji is interacting with everyone from their own viewpoint. The guru keeps all of these relationships going on all levels at once, and at the same time doing work on other planes with many other beings. Everyone gets what they need.

A perfected being sees exactly where individuals are in their karmic evolution in the same way you might see an automobile at a particular stage in its assembly. To see the entire assembly line is to know we are all One, that we are all God. It’s seeing beyond time, seeing that it’s all perfect.

Swami Muktananda comes from the Shaivite (Shiva) side of Hinduism, which emphasizes shakti, or power, as distinct from the followers of Vishnu (Vaishnavs), who tend more to the bhakti, the loving or devotional side. Muktananda meditates on his guru, Nityananda, as a powerful way to shift his identity to the enlightened state. This meditation is a way to bring the qualities of the guru—wisdom, compassion, peace, and love—into yourself. In his autobiography, Muktananda describes how he came to this meditation.

This is Muktananda’s method for merging with the guru. As you keep doing it, you get to a point where you start to fully identify with the guru and you flip your whole consciousness around until you are the guru. As a child identifies with a parent, you just start to absorb this whole other being. Muktananda would get so flipped out, he wasn’t sure who he was most of the time during this sadhana.

Hide and Seek

Maharaj-ji is a mirror of our highest Self. Each of us has within us many levels of consciousness, though most of the time we don’t experience them. We never got to play with Maharaj-ji at his highest level, because we could only play at our highest level.

The last time I saw Maharaj-ji, I looked back when I was leaving the temple. I saw him sitting looking at the hills, and it was just like Shiva sitting in the Himalayas. He seemed to embody that quality of absolute stillness, at one with pure consciousness. He was like part of the mountain, the same as the universe around him.

I wanted to be able to share that with him. I could feel that vibration from him, but I couldn’t live there yet myself. I didn’t have the key to that level of consciousness. Each person has the ability to resonate with that state, like a sympathetic string on an instrument. The more conscious being, the higher vibration, always sets the tone. Slipping in and out of those higher states is seductive.

That’s what darshan is, seeing or getting a glimpse of that place. It makes you yearn for it. The guru creates that aspiration just by being here. There’s a vibrational field around Maharaj-ji; we all know it. It’s like an aura. The higher vibration brings you up as far as you can go, even though he’s still beyond it all.

The difference between a guru and us is that he inhabits those planes always, with no discontinuity. He lives in the ![]() tman, the One. We experience our consciousness as separate, but through the guru’s love we begin to experience it as shared in common, because love dissolves boundaries, love is universal. Maharaj-ji brings us as far as we can go into that state of merging into love before our individuality kicks in and we hold back out of fear of letting go. That’s the crux of the whole matter.

tman, the One. We experience our consciousness as separate, but through the guru’s love we begin to experience it as shared in common, because love dissolves boundaries, love is universal. Maharaj-ji brings us as far as we can go into that state of merging into love before our individuality kicks in and we hold back out of fear of letting go. That’s the crux of the whole matter.

For the close devotees around Maharaj-ji the approach to those higher states has been the bhakti path: love, service, kirtan, devotion. Dada Mukerjee asked for nothing; he was just there, serving, serving, serving. That’s what Siddhi Ma has done, continued serving Maharaj-ji until she has become absorbed into him. Those old devotees around Maharaj-ji; they’re just serving him. They have no other motive except love.

Dada (an affectionate term for “elder brother”) was a professor, the head of the Economics Department of Allahabad University. His devotion was a model for me of this form of guru yoga. He pursued total surrender to Maharaj-ji. He was a highly intelligent man who in his own right was the editor of the leading economic journal in India. In the latter part of his life he did everything solely in relation to Maharaj-ji. He kept his job because Maharaj-ji told him to. When serving Maharaj-ji, he became like an extension. It was like looking at your hand. When you go to make a fist, do you notice how your fingers come together? Each finger doesn’t think for itself. Your brain sends a message, and the fingers come together. Dada was like a finger on Maharaj-ji’s hand. There was nothing in him that was wondering, “Should I do it, or shouldn’t I?” or, “But you said . . .” or anything like that. He was just a perfect extension, like Hanuman is for Rama.

Dada Mukerjee. Photo by Rameshwar Das.

One day we were sitting in the courtyard at Kainchi. Dada was passing in front of us on his way somewhere, when Maharaj-ji called to him to do something. But we saw that Dada actually started turning toward Maharaj-ji a split second before Maharaj-ji called him. That was the level of attunement.

That’s the Hanuman mode, serving through love, opening and opening until you become the Beloved or the Beloved becomes you. You’re absorbed into that consciousness, and the Beloved’s being permeates yours. Then the ego perception shifts to the soul perception, the whole world is radiant, and the grocery store is your temple, full of souls. Sometimes when I’m speaking to an audience, if I drop into that place, Maharaj-ji’s presence enters the room and then there’s only one of us. We are all touching the ![]() tman.

tman.

Hanuman said, “O Rama, sometimes I find that You are the whole and I a part, sometimes that you are the Master and I Your servant; but O Rama, when I have the knowledge of Reality, I see that You are I and I am You.”

—Sri Ramakrishna4

Once, Dada had been missing Maharaj-ji very much, and he was sitting at night correcting examinations from his economics class at the university. Finally, after locking the house, he went to bed. In the morning nothing had been disturbed, but across the whole page of the top examination paper was written, “R![]() m R

m R![]() m R

m R![]() m R

m R![]() m R

m R![]() m R

m R![]() m R

m R![]() m,” in Maharaj-ji’s handwriting.

m,” in Maharaj-ji’s handwriting.

On another occasion, Didi, Dada’s wife, said to Dada, “I hear something in the next room.” Their bedroom was near the room they kept for Maharaj-ji, although he wasn’t there at the time. When they went in there, as they opened the door, they heard something. There were tracks all up to the ceiling on the wall. Maharaj-ji’s footprints were all over the walls.

Once while Maharaj-ji was away, Didi made kheer, a sweet dish of rice and milk and put it right under the picture of Maharaj-ji. One of the young children came running out of the room, excited. They all went in, and the kheer was dripping down from his picture. Maharaj-ji had taken it.

In similar fashion Maharaj-ji scolded a pujari for not having remembered to put milk out for the murti of Hanuman before he locked up the temple for the night. So the man went and did it. When he unlocked it the next morning, the milk was all gone.

Dada experienced Maharaj-ji turning into Hanuman:

We were walking around and Babaji caught hold of my hand. When he did that I would sometimes experience such a heavy pressure that I felt my hand would break. He was leaning so heavily on me, I was afraid that if I fell down, he would also. It was early afternoon and we came before the mandir when many people were sitting. Babaji sat before the Shiva temple, my hand locked in his. He said, “Baitho, baitho.” [“Sit, sit.”] I wanted to extricate myself, but could not.

I was feeling as if I were suffocating, as if my breathing were coming to an end. My hand was so tight in his grip that there was no question of getting free. Then I saw, not Babaji, but a huge monkey sitting there, long golden hair over the whole body, the face black, the tail tucked under the legs. I saw it clearly. I closed my eyes, but still I saw it. After that, I don’t know what happened.

At ten o’clock that night, I found myself sitting alone down by the farm. Purnanand, from the tea shop, came and said, “Dada, here you are. We have been searching for you all evening.” He took me back to the ashram.

Babaji had not gone inside his room yet; he was sitting on a cot and many devotees were around him. As soon as we came across the bridge and near the temple, somebody said, “Baba, Dada has come.” He just said, “Accha, thik hai.” [“Very good.”] There was nothing to take notice of, nothing to be excited about. I was feeling very depressed. I didn’t want to talk; I just wanted to be alone and go to bed.

The next day Guru Datt Sharma and Siddhi Didi and others kept asking me what had happened. They told me we had been sitting there in front of the Shiva temple, surrounded by many people, when suddenly we were both missing. Then Baba and I were seen walking on top of the hill. An hour or two later, Baba returned alone. I knew what I had seen—that it was actually Hanuman. It was not a dream, not a mistake. How the time passed, I do not have any recollection.5

That’s another aspect of Maharaj-ji, of course, in which he is very intimately related with R![]() m and Hanuman. Just how intimately related was a source of some mystery to those of us around him. Other people also reported seeing him turn into Hanuman. Every time one man came near Maharaj-ji, he would take one look and pass out cold. When they revived him, all he could say is “All I saw was a huge monkey.” Perhaps on another plane, Maharaj-ji is Hanuman, he is Hanuman manifest at this time. But even that is only a game, because a being who is nobody is everybody, and he may be taking that form, because that aspect of God is connected with that particular situation. I think it is limiting to call him anything at all.

m and Hanuman. Just how intimately related was a source of some mystery to those of us around him. Other people also reported seeing him turn into Hanuman. Every time one man came near Maharaj-ji, he would take one look and pass out cold. When they revived him, all he could say is “All I saw was a huge monkey.” Perhaps on another plane, Maharaj-ji is Hanuman, he is Hanuman manifest at this time. But even that is only a game, because a being who is nobody is everybody, and he may be taking that form, because that aspect of God is connected with that particular situation. I think it is limiting to call him anything at all.

In a way a being like that is everywhere you think of him. He is, and in a funny way there’s nothing you can say he isn’t. He has been known to show up in many places simultaneously, to appear and disappear. Whenever possible, he denied everything, always leaving you with your doubts. If you tried to test him, you’d always come away thinking he was just an old man in a blanket. Only those who say, “Forget testing, I’m going!” begin to experience his grace.

Maharaj-ji can be in thousands and thousands of places. Many people have visions of Maharaj-ji, dream about him, have visits from him, see him, or remember him in a way that’s very vivid—and in each case he is with them. Or an aspect of him is there, and the aspects can be as many as there are thoughts. A realized being can send out his or her thought form, which is an aspect of that being, and that thought form takes on reality. It becomes manifest somewhere and is truly seen by the person having darshan in a vision, dream, or even ordinary waking consciousness.

The quieter your mind is, the more open you are to that meeting with the guru in the heart. Your thought brings the guru to you the moment that thought is pure enough, intent enough, single-minded enough.

The guru only exists to serve the devotees; that’s the only reason for the guru’s existence. And seeing the guru in the physical form is only another part of the dance, another part of the illusion.

Dada once said to me, “I’m closer to Maharaj-ji when I’m away from him than when I’m with him. Because when I’m with him, my senses get in the way. I get lost in enjoying being with him.”

When Dada says, “He’s just Baba,” that really says it all. Dada was totally blown away; he was full of awe. Dada was as close as you could get to knowing Maharaj-ji, and yet his awe kept him from becoming Maharaj-ji, from doing the final thing that would have let him merge. It’s like the bhakta Hanuman, who tells R![]() m he’d rather remain a loving servant than sit with him.

m he’d rather remain a loving servant than sit with him.

Maharaj-ji had devotees at many different levels of attachment to him. Some were attached to his body and saw him as a grandfatherly figure. Many Indian families were like this with him. He had many devotees who were villagers, very simple people. They each had different karma that created a certain kind of relationship with Maharaj-ji. For one he was like a grandfather, for another a friend, for another a teacher, for others Hanuman, and for others he was God beyond any concept.

When he was in the body there were few big gatherings, except a few festivals at the temples, but no great big public things. His simplicity and humility were awesome. He wore a blanket, a dhoti (a cloth wound around the lower portion of the body), and a T-shirt, and he sat on a wooden bed, or tukhat. When you entered a room he was staying in, you were struck by the absence of everything you would associate with somebody’s lived-in bedroom. There was no reading lamp, no books, no evidence that a human being was living there. He would just walk in, sit down on this wooden bed, and there he is and that’s his universe. And he was fulfilled. There are many pictures of him just sitting by the side of a road. That was enough for him.

Some devotees simply saw Maharaj-ji as God Incarnate. They were very humble before him; they asked for nothing. They just served him in any way they possibly could. They felt blessed just to have a being like that in form. He never had any big ashrams, and compared to the well-known saints like Sai Baba and Anandamayi Ma, his scene was very small. Most of the time he would send people away soon after they came. He would let them stay five minutes and tell them to leave. You couldn’t collect him, you couldn’t hold on to him. You couldn’t just hang out however you liked.

In this “not two” nothing is separate, nothing is excluded. No matter when or where, enlightenment means entering this truth.

—Seng-ts’an, Third Patriarch of Zen6

If you’ve touched that higher place, you know where you’re going. Talking or reading about Oneness is not being in the One. As I understand it, when you become One, the objective universe ceases to be. There’s no knower, only knowing. Subject and object become one. In truth Maharaj-ji and I are one. But I can’t stand it; my ego can’t exist there. So I will just keep serving R![]() m and Maharaj-ji until there’s no difference between us.

m and Maharaj-ji until there’s no difference between us.

O servant, where dost thou seek Me?

Lo! I am beside thee,

I am neither in temple nor in mosque; I am neither in Kaaba nor in Kailash:

Neither am I in rites and ceremonies, nor in Yoga and renunciation.

If thou art a true seeker, thou shalt at once see Me: thou shalt meet Me in a moment of time.

Kabir says, “O Sadhu! God is the breath of all breath.”

—Kabir7

Maharaj-ji is not bound by time and space. Time and space are within him. In that sense, these incarnations we are in are maya, or illusion; they’re not real. From where he sits it’s all simultaneous. The planes of consciousness, past, present, and future coexist at the same time like dreams one within another. It’s a continuum. It’s all One, or as he used to say in Hindi, “Sub ek.”

Maharaj-ji usually wore a blanket. Dada Mukerjee comments:

People asked me so often, “Why does Babaji go on covering himself with a blanket?” Not only would he wear a blanket in the winter when it was cold, but also in the hottest summer months. I used to say that there were two blankets: one blanket covered his physical body, that we all knew. It was not indispensable; it could be thrown off. Some miracles were no doubt done through it: he would be taking something out from under it, sometimes the blanket would be very heavy, sometimes it would be light, and there was the smell of a baby in it. But there was another blanket that was inside. He was covering all his sadhana, all his siddhis, all his achievements, all his plans and programs. Why was he hiding all this? Perhaps it was for our protection, perhaps to save himself from crowds of followers. We cannot know.8

People gave Maharaj-ji blankets. When he finished with a blanket, it suddenly became much smaller, and he said, “Why are you giving me these blankets that are too small?”

Being with Maharaj-ji not only expanded my conceptual horizon—he certainly blew my mind—he also filled my heart. At the same time there was no clinging in him. That quality of detachment and emptiness was combined with such intense love, an oceanic love that pervaded every being around him. He said that attachment grows both ways, but he also said, “Saints and birds don’t collect. Saints give away what they have.” He often quoted favorite lines from Kabir’s poems like, “I am passing through the marketplace, but I am not a purchaser.”

The blood in us all is one. The arms, the legs, the hearts are all one. The same blood flows through us all. God is one.

Everyone is God; see God in everyone.

It is deception to teach according to individual differences in karma—all are one, you should love everyone, see all the same.

—Maharaj-ji

At first I was awed by a presence so powerful that I felt purified just by being near him. Even now, bringing him into my heart does the same thing. I never learned much Hindi, but to me it didn’t matter. Words were only the surface of that relationship.

At the time we got to him Maharaj-ji appeared to us as a revered saint or guru who stayed in various temples or ashrams in northern India that were built for him. He would appear in one, stay for a little while, and then, just when everyone was settling down to hang on to him forever, he would be gone. In the middle of the night he’d get someone with a car to take him off, and he would disappear. Then he’d turn up somewhere else, staying here and there with this or that devotee, traveling as the wind of God moved him. Only after he left his body did we discover that was only one aspect of his life and that he had a family.

When I was with him when he was in the body, I experienced his being at many levels. Personally he could be playful and funny, frustrating and repetitive, sweetly childlike, stubborn, like an old man or a little child, very concerned or totally indifferent. We experienced that person because that was our desire, our need for a loving guide. But what we perceived as a personality was in reality more like the changing of the weather, because he had so little attachment to it. We saw the cloud of Maharaj-ji’s maya, the illusion, though behind it was the sun of the ![]() tman.

tman.

Simultaneous with this seemingly personal relationship was the palpable power of his presence. There was awe and respect on the part of the devotees too. It was like standing next to a mountain with its upper reaches vanishing in the clouds. When I was in his presence, I experienced an ecstasy and a depth of love—a drunken kind of love where I would often find myself dissolving into tears. When I started going into that, he would interrupt with small talk about others, “How much money does Stephen make?” or something like that, to bring me back. He kept me firmly down on the physical plane to do my work. He didn’t allow me to just float around in bliss very much.

On a deeper level, when he asked me why I returned to India, I told him I had come to purify myself more. He said, “I am always in communion with you.” Now I understand that to be the case. He is with me always. Sometimes people’s reactions are not to me, but to him. At times I don’t even feel his presence; he’s just coming through me.

The rest of the time I just feel as though I am constantly hanging out with him and he is drawing me in toward himself, toward that place in myself, just pulling me ever so gently. There’s no rest. The process is continuous. Everything that happens to me is part of his teaching, if I can remember. If I get uptight about something, I hear him saying to me, “Well, you’re still caught, aren’t you? Too bad . . .” I talk with him all the time at that level.

As I look back over the times I was with him when he was in the body, when I was able to be at his feet, from the beginning the figure and ground were slowly shifting. Initially there was a fascination with having all this love and attention from Maharaj-ji, K.K., and Hari Dass Baba. Having a guru, having this man whom everybody worshiped giving so much love to me, and feeling completely at home in this strange culture—I was completely hooked.

At first all that fed my ego. I came with a big ego, a great sense of specialness. After all, I was a Harvard professor who had come thousands of miles from America! But then I began to see that however lovingly he treated me, it was no different from the way he treated anyone else, including the sweeper. My self-importance got no confirmation, and I was the only one who even noticed. And after a while my need to feel special began to dissolve in the ocean of his love. Simply opening myself to that love was more blissful than any ego gratification.

That was back in 1966–67. After that I was away from him in the States, and I had to make a new kind of connection. When I returned in 1970 I wasn’t as fascinated by the body form as the Westerners who had just arrived. Although he could always pull me into it, I began to feel less involved with the day-to-day drama of being with him. It became more like theater, an entertainment to distract us from the intense transformation going on inside. There was a point where I saw that he was everywhere and in everything.

One day he called me over and asked, “What do you do about your mail?”

“I answer it,” I said.

“Don’t save your letters,” he said.

He had just received two letters. He put one on top of his head, and the other he threw into the wind unread. A cow started eating it. I got very upset.

Another time I got a letter at the post office in Nainital and then got on the bus to go to the temple. I walked into the temple, and Maharaj-ji asked, “What’s in the letter?” I started to tell him, and he kept adding things I had missed. I knew that if he knew there was a letter, he knew what was in the letter. So why was he asking?

I began to see how empty all these forms were. I’d look at him, and I’d know he knew I knew he knew, and it just kept going deeper and deeper. It’s like a joke where you laugh, and then you laugh again at another level, and then you laugh again at a third level.

In a Buddha there has never been

anything that could be said to be there

Just as a conjurer

Tries not to get caught up in his illusions

And therefore by his superior knowledge

Is not attached to magic forms,

So also the wise in Perfect Enlightenment

Know the three worlds to be like a magic show.

Liberation is merely the end of error.

—Gampopa9

The Little Things

Maharaj-ji’s devotees depended on him for more than their spiritual welfare. They also looked to him for the mundane details of life. Because he lightened their burdens and anxieties, it also gave them faith to pursue their inner lives. The way Maharaj-ji took care of his devotees, how he looked after them, responded to their needs, and just showered his love on them, deeply endeared his followers to him. He spent most of his time helping people and advising them on the details of their personal lives, families, businesses, jobs, health problems, marriages, emotional worries, school exams, financial stresses, and politics. Dealing with the minutiae of so many hundreds of lives would have quickly overwhelmed a normal person, but his generosity of spirit and loving-kindness buoyed many who were adrift on the sea of existence, so they could then turn their attention toward God. As I watched people from all walks of life coming to him with their problems, I saw directly how his compassion led him to spend all this time listening and helping, and how focused his life was on the needs of others.

Maharaj-ji said, “I don’t want anything. I exist only to serve others.”

He didn’t teach highfalutin philosophy. But he showed me that the spirit can be transferred into people’s hearts by the simple acts of loving them, feeding them, and remembering God. He said Westerners had been denied food. He must have meant spiritual food—none of us lacked for basic sustenance.

He felt each devotee’s every need, because he was one with everyone, and yet there was also a level of detachment that comes from seeing how it all is. He protected people from danger and comforted them in times of grief or anxiety. Often they had only to remember him, and he would appear. At times he stood by as people died or endured some suffering, because he recognized their karma. Even then he helped to lighten the load of grief or pain or helped them extract the needed wisdom from the situation.

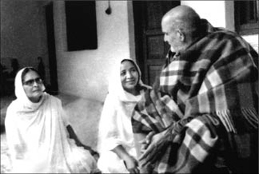

This photograph of the Sah family sitting with Maharaj-ji hints at the subtlety of this mosaic. Each individual here is being fed by his presence. and each is receiving what their karma allows. The elder just to the right of Maharaj-ji is a devotional scholar who is reinforcing his ideas about God. The child is experiencing the closeness of family, the paternal love of a grandfather. The wife is simply drinking of the ambrosia, the bliss of being in the presence of God. On the right, the brother has a quiet and deep devotion, a simple faith. The cousin on the left is going in and out, merging in the love.

Sah family with Maharaj-ji. Photo by Rameshwar Das.

All these experiences add up to a transmission, a deepening of the moment, into the very heart of Being, the eternal moment of God. This is a moment shared on many planes, a silent pause in a moving sea of love.

We enter into each other when we are in each other’s presence. If you’re not threatened, you can relax your separateness, let it fall, and enter into a kind of liquid merging with other beings. Sitting with Maharaj-ji is total contentment. Nothing may be happening, the conversation may be completely trivial, yet there is a richness of presence, of emptiness, of a unity that transcends blood family to become spiritual family.

When I returned to India in 1970, Maharaj-ji had gone from the temple in the hills, and I couldn’t find him. Other Westerners were in the same boat. We finally found him, or he found us, in Allahabad. Then he sent us on our way, saying, “See me in Vrindavan.” So I went to Delhi, and then went on several weeks of pilgrimage with Swami Muktananda.

When we finally returned from our pilgrimage in March, it was the time of year he would be up in the mountains. I didn’t want to stop in Vrindavan, because I knew he wouldn’t be there. But the group insisted, and so we went there. We arrived at the temple at about 8:30 A.M., and the place was deserted. I was so disappointed. It was the second time I had gone to that temple and he wasn’t there. And he had said he would see me in Vrindavan. The pujari said, “Oh, Maharaj-ji is in the mountains. Go see him in Kainchi.”

So I said, “Well, let’s not waste any time here. Let’s go to the mountains.”

So we went out and got in the car, and just as we were putting the key in the ignition, a little Fiat drove up, and who was sitting in the front seat next to the driver but Maharaj-ji. He got out looking utterly bored and walked into the temple.

We ran to the driver and asked, “What is he doing here?”

The driver said Maharaj-ji got him up at 2 A.M., saying, “Come on, we have to go to Vrindavan right away!”

Then when they got to Agra he said, “We still have an hour to wait.” So they went and visited a judge.

Then he said, “Come on, let’s go,” and they drove up just at that moment. That’s timing. That’s cosmic show biz. Maharaj-ji fulfilled his promise to meet us in Vrindavan, so we wouldn’t be disappointed. He performed this deeply caring act as if it were totally ordinary. As he walked past us into the temple, there was no outer demonstration at all.

In a collection of devotee stories titled Divine Reality there is a story about Maharaj-ji coming to visit one of his devotees, the civil surgeon in the city of Jhansi. It was during World War II. The man made a bed for Maharaj-ji and slept on the floor next to him in case he should need anything during the night. About 1 A.M. he heard Maharaj-ji tossing and turning and asked him why he was restless. Maharaj-ji gave him his blanket and asked him to go and throw it in the water. It was a dark night and the lake was some distance, but Maharaj-ji insisted on his going right away. When he returned before dawn, Maharaj-ji told him that his son, an army officer, had been in a German attack, jumped off a ridge, and gotten stuck in a marsh. Germans had fired on him from above, and taking him for dead, they left. Maharaj-ji said, “All those bullets got stuck in my blanket, and their heat made me uneasy. When you threw the blanket into the lake, I was relieved of my discomfort.”

The blanket was new, and there were no holes in it. The surgeon didn’t understand what was going on, but was comforted to know his son was safe. Some days after Maharaj-ji left, the man’s wife received a letter from their son relating the same circumstance described by Maharaj-ji and expressing his surprise that an unknown power had saved him from a rain of bullets.10

“Never disturb anyone’s heart. Even if a person hurts you, give him love.”

“I can’t get angry with you, even in a dream.”

“If you can’t love each other, you can’t achieve your goal.”

From stories that have been passed on to us by the close Indian devotees who traveled with Maharaj-ji and spent time with him at places like Kainchi and his “winter camp” in Allahabad, there was a great sense of intimacy and playfulness as their lives revolved around him. At Dada’s house in Allahabad they slept on mattresses on the floor and ate together. Maharaj-ji would sit on the end of their beds and joke with them. Dada’s mother and auntie would sit preparing vegetables and cooking. While Maharaj-ji was in his room, the others would be exchanging intimate stories about him. When he emerged he would tease them about reciting lies behind his back. Everyone’s habits and failings, like Dada’s smoking, would come in for some discussion, all done in an atmosphere of affection and humor.

With such close devotees he was informal, intimate, and colorful in his language. Because of our lack of knowledge of Hindi and our unfamiliarity with the culture, we sometimes missed the delicious details. Once at Kainchi one of the Western women who was living outside the ashram reported that her rented room had been broken into and some of her things had been stolen. Maharaj-ji launched into a lengthy and heated response that was translated as, “Maharaj-ji says you should keep your door locked.” Some of the Westerners who had learned a fair amount of Hindi heard what he actually said, which was, “Those stupid sister-fuckers, they leave their doors open for any passing thief!”

He was sometimes called “Latrine Baba,” partly because he put in the first flush toilets in Kainchi, but probably also because he used foul language. It always seemed affectionate. I guess the Indians were embarrassed, because they wouldn’t translate it for us.

We were the junior members of this family, but even so he lovingly kidded us and occasionally included us in the much sought after honor of being abused—teased or lovingly insulted—by him. Within weeks we felt fully welcomed under the shade of his umbrella and began to get at least some sense of the delights that the Indian devotees had enjoyed for so many years.

One time Maharaj-ji was nudging those of us who enjoyed an occasional toke of ganja or charas, marijuana or hashish, to cease indulging. He was rarely moralizing or alarmist about such habits, pointing more toward how they distracted one from the pursuit of God. To buttress his case Maharaj-ji brought in Purnanand Tewari, a longtime devotee and a farmer and owner of the chai wallah (tea stall) outside Kainchi. Berating Purnanand at length for wasting his time smoking charas and thus spending the money that was to feed his family, Maharaj-ji excoriated him for his weak moral fiber. Through it all Purnanand sat looking humble and guilt-ridden, the picture of contrition, confessing to each of Maharaj-ji’s accusations, “Yes, Maharaj-ji, yes, Maharaj-ji!” Though we took his point, most of us saw this as an affectionate charade.

Even our receiving the news in America that he had left the body occurred in a compassionate and graceful way. His death was part of the fabric of how he lived in us. Rameshwar Das had come to visit me in Franklin. Soon after his arrival a telegram was delivered to my father saying that “Maharaj-ji has dropped his bojay” (telegraphic mangling of “body”). As the news spread quickly, others came to join us. Being part of his spiritual family gave us all solace and support as we worked to come to terms with this cataclysm in our firmament. I was surprised to find myself not really grieving. There was really no change in my relationship with him.

Maharaj-ji. Photo by Balaram Das.

I felt a curious emptiness. It was scary, because I had really only wanted to get away from him for a little while, until I was ready to go back to the rigors of sadhana, and now he had gotten away from me. The power had been taken out of my hands. I could, in truth, have gone back to India before that if I’d wanted to. But I didn’t want to. I was enjoying “name and fame” too much and rationalizing it all perfectly.

But all the time Maharaj-ji was there in my consciousness. When I felt his presence, I thought maybe I was creating it, and when I denied his presence, I felt I was pushing away something that was in fact true. So he was both there and not there. Either way, he was still here.

How to describe the degree of caring and solicitude Maharaj-ji manifests for those who remember him? To compare him to a parent or a doctor, lover or spouse vastly understates the case. His level of compassion is based on being it all. He actually feels the fear, anxiety, and pain of his devotees, because he is them. And at the same time he is beyond it all. His compassion comes from the deep wisdom of how things are, not just from sympathy with our temporal misery. His true focus is on the soul.

There were women who took care of Maharaj-ji—the Ma’s or mothers, single women, widows, and grandmothers who were able to take time away from their families. In all the time I spent at the temple I never even knew they existed. They stayed in the back, always out of sight, busy taking care of Maharaj-ji out of complete love and devotion. Sometimes he was very fierce with them. Once when they didn’t bring his medicine on time, he said, “If you don’t take care of me, I’ll turn your minds against me.”

It’s Only Love

Maharaj-ji’s teaching is love. That love stays with you wherever you are. The more open you are, the more you can receive the love. It’s the beginning, the middle, and the end.

Jivanti Ma, Siddhi Ma, and Maharaj-ji.

At first I was seeing him a lot through my heart in an emotional way, like having a good father who loved me so much, and I just kept basking in that affection. But I was stuck in an interpersonal, emotional, romantic kind of loving. It’s not pure love, like Christ-love. I kept trying to make Maharaj-ji into a personality, and he wasn’t. My mind was interfering with the power of his love, but I couldn’t do much about it, because my mind was so dominant. He kept saying, “Ram Dass is so clever.” I’m simpler now, which is nice. I’m still smart, but I’m not so clever.

I went through a transformation from personal to impersonal love for Maharaj-ji. At first I brought along all my old habits of personal love. Then I began to see how impersonal it is. He was just there, laughing behind it all. And it was still all love, so much I could barely stand it. It was anguish for a while, but I feel much closer to him now.

I remember once in Delhi we had found Maharaj-ji at the house of an old devotee named Soni, and we had all rushed there to his feet. We were all in ecstasy that we had gotten to him in the bedroom. I was made much of as a leading this and that, and everybody was fawning all over me. We went outside and were fed many sweets. I was standing by the door when Maharaj-ji came out of the bedroom to go to the car. He walked within six inches of me, but went right by me as if I were a lamppost. There wasn’t one iota, not a hint of recognition. This being, who was always patting me and doing all kinds of loving things, just walked by me as though he was passing somebody on the street. He wasn’t even intentionally ignoring me; there was nobody “busily walking by.” That took our relationship to a whole new level for me.

A Cup of Ocean, Please

The guru is just here. The guru is just sitting around doing nothing really, just manifesting. But what do you do? Can devotees do something to open themselves to the guru? Ramana Maharshi says, “from the point of view of the disciple, the grace of the Guru is like an ocean. If he comes with a cup, he will get only a cupful. There is no use complaining of the niggardliness of the ocean; the bigger the vessel, the more he will be able to carry.”11

When I was with Maharaj-ji for long periods, I would have time to reflect about who he really was. We would sit across the courtyard and watch him. I’d be thinking, “Who is this?” “What are we about?” “What is this process?” Again the form started to become empty, really empty. I started to feel caught in some kind of tape loop in my mind, and I saw that I had to go deeper than the form and the linear human interaction. Maharaj-ji was so incredibly vast, yet I couldn’t get to him as long as I kept seeing that form as real. So that reality gave way to a deeper level of being, where I kept feeling him surrounding me and the oceanic quality of his presence.

All I can ever ask of Maharaj-ji is to make me a pure instrument of his will. I just want to keep surrendering to him. I no longer even have a desire to be enlightened. I’m not interested in being done—it’s not a realistic thing for me. It may happen or it may not, I don’t know.

More and more I am less and less in evidence to myself. More and more I’m just whatever it is I am doing at the moment. It’s just happening. I’m just action. I’m not acting self-consciously. But it’s different from the unconscious action I’ve performed most of my life. All I want is to become like a finger on the hand of his consciousness, or like Hanuman, whom Maharaj-ji referred to as the “breath of R![]() m.” I’m perfectly content to be the breath of Maharaj-ji.

m.” I’m perfectly content to be the breath of Maharaj-ji.

Maharaj-ji is not going anywhere. As St. John says, “He that sent me is with me, he hath not left me alone. I do always the things that please him” (8:29). It’s up to us to make the effort to reach up, to look within, to quiet our minds to make space for him. Then, as he said, “Bring your mind to one point and wait for grace.”